Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

When the demagnetized state of a polycrystalline

sample before application of the field is isotropic (a

random distribution of non-1801 magnetic domains

over sample volume), the MS measured in the direc-

tion parallel to the field, l

8

, saturates at l

s

which is a

characteristic of the material. The corresponding de-

formation in the perpendicular direction l

>

saturates

at l

s

/2 in this case. Generally, the ratio between l

8

and l

>

depends on the magnetic state at zero field

because the distribution of the volume over domains

is not necessarily random. However, the value l

s

¼

2/3(l

8

l

>

) remains independent of the demagnetized

state. For a cubic polycrystal (Belov et al. 1983):

l

s

¼ð2=5Þl

100

þð3=5Þl

111

ð5Þ

Several microscopic mechanisms are responsible for

the anisotropic MS (Belov et al. 1983). First is the

magnetic interaction between a pair of magnetic

atoms, which depends on the orientation of the mag-

netic dipoles relative to the crystallographic axes. The

corresponding dipolar MS is essentially anisotropic,

but it is usually very small. Second is the MS caused

by the variation of the exchange energy with inter-

atomic distances. This mechanism is responsible

mainly for the volume MS but can have anisotropic

contributions for some substances with low-symmetry

lattices. The most prominent mechanism is the inter-

action between the anisotropic electron shell of an ion

and the crystal field (CF). This single-ion mechanism

is responsible for the so-called giant MS (l410

3

)in

many rare earth and actinide compounds.

If the magnetic ion has a nonzero orbital momen-

tum, M

L

, the orientation of the total magnetic mo-

ment, M

J

, by the magnetic field causes the rotation

of M

L

. The ‘‘disturbance’’ of the crystal field by the

rotation of the anisotropic electron shell leads to

the anisotropic lattice deformation, i.e., MS. For a

simple case of a paramagnet, the relation for the

magnetoelastic deformation has been derived:

l ¼ AH

2

þ CHtanhðg

j

m

B

H=k

B

TÞð6Þ

where A and C are the functions of the direction co-

sines of the field and the strain. The first term is pro-

portional to Van Vleck susceptibility while the second

term reflects the interaction between the magnetic

moment and the crystal field. At low H, both terms

yield a quadratic dependence of H. The second term

saturates at high H.

The single-ion MS caused by the interaction of the

4f shell of R ions with the CF at T ¼0 can be de-

scribed by the following (Clark 1980):

lð0Þ¼DaJðJ 1=2Þ/r

2

4f

S ð7Þ

where D is a coefficient determined by a given crystal

lattice, which depends on the CF parameters, the

elastic modulus, and the concentration of rare earth

ions, a is the Stevens factor that depends on the

atomic constants of a 4f ion, /r

2

4f

S is the average

radius squared of the 4f shell, and J is the total an-

gular momentum.

The a factor is determined by the shape of the 4f

electron charge cloud. For the 3 þ ions of cerium,

praseodymium, neodymium, terbium, dysprosium,

and holmium ao0 (an oblate 4f cloud), while for

samarium, erbium, thulium, and ytterbium a40

(a prolate 4f cloud) (see Localized 4f and 5f Mo-

ments: Magnetism). The sign of single-ion MS chang-

es in a series of heavy rare earth ions between

holmium and erbium. Similar changes occur in rare

earth intermetallic compounds. The MS constants of

RFe

2

are presented in Table 1 for the ground state (at

4.2K) (adapted from Clark 1980, Belov et al. 1983,

Andreev 1995). For a particular symmetry, the MS in

Table 1

Magnetostriction constants of RFe

2

at 4.2K.

a

Compound EMD m (m

B

) l

100

( 10

3

) l

111

(exp) ( 10

3

) l

111

(calc) ( 10

3

) o

s

( 10

3

)

SmFe

2

[110] 3.1 0.03 4.1 3.8

GdFe

2

[100] 3.8 0.05

b

0.05

b

0

TbFe

2

[111] 5.8 4.5 5.2

DyFe

2

[100] 6.8 0.07 B3.0

c

5.0 5.4

HoFe

2

[100] 6.9 0.75 B0.78

c

1.9 6.3

ErFe

2

[111] 6.0 1.85 1.85 8.8

TmFe

2

[111] 3.7 3.6 4.4

LuFe

2

[100] 2.8 0.09

b

0.09

b

0 4.1

YFe

2

[111] 2.8 0.05

b

0.05

b

0 2.2

UFe

2

[111] 1.2 0.23 3.0 40 1.6

NpFe

2

[111] 2.6 8.0 o0

a EMD, easy magnetization direction; m

m

, magnetic moment per formula unit; l

100

and l

111

(exp), experimentally determined anisotropic

magnetostriction constants; l

111

(calc), l

111

values calculated with Eqn. (7) using the experimental value for ErFe

2

to determine D factor; o

s

,

spontaneous volume magnetostriction. b Saturation magnetostriction, l

s

, of polycrystal. c Values extrapolated to 0K from the high-temperature

range (180–300K).

770

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

these compounds (except for HoFe

2

) is determined

mainly by l

111

(l

100

5l

111

). The l

111

values calculated

with Eqn. (7) are also given in Table 1. D was de-

termined using the experimental value for ErFe

2

. The

signs of experimental and calculated l

111

coincide.

The magnitudes also agree satisfactorily. The CF

mechanism of giant MS in compounds with nonzero

L moment of the R ion is corroborated by the fact

that the compounds with nonmagnetic R ¼Y, Lu,

and with gadolinium (L ¼0) exhibit MS of two or-

ders of magnitude less. Giant MS is also observed in

UFe

2

and NpFe

2

, the actinide analogues of the RFe

2

group (Table 1).

According to the theory of magnetoelastic interac-

tion (Callen and Callen 1963), the field and temper-

ature dependence of the magnetoelastic constant of

lth order is determined by the magnetization:

l

l

ðT; HÞ

l

l

ð0; 0Þ

¼

#

I

lþ1=2

L

1

½mðT; HÞ

ð8Þ

where

#

I

lþ1=2

ðxÞ¼I

lþ1=2

ðxÞ=I

1=2

ðxÞ is a modified hy-

perbolic Bessel function and L

1

(m) is the inverse

Langevin function of the reduced magnetization m (T,

H) ¼L (x) ¼

#

I

3=2

ðxÞ¼cothx1/x. Here x ¼(m

B

H

mol

/

k

B

T) in the molecular field model. In the low-tem-

perature region:

l

l

ðT; HÞ

l

l

ð0; 0Þ

¼ m

lðlþ1Þ=2

ð9Þ

The single-ion model allows one to describe the MS

also in the metals of the iron group. The orbital mo-

ment of 3d electrons is nearly quenched due to the CF

and is usually very small. Nevertheless, the single-ion

contribution to the MS exceeds the dipolar contri-

bution in these compounds.

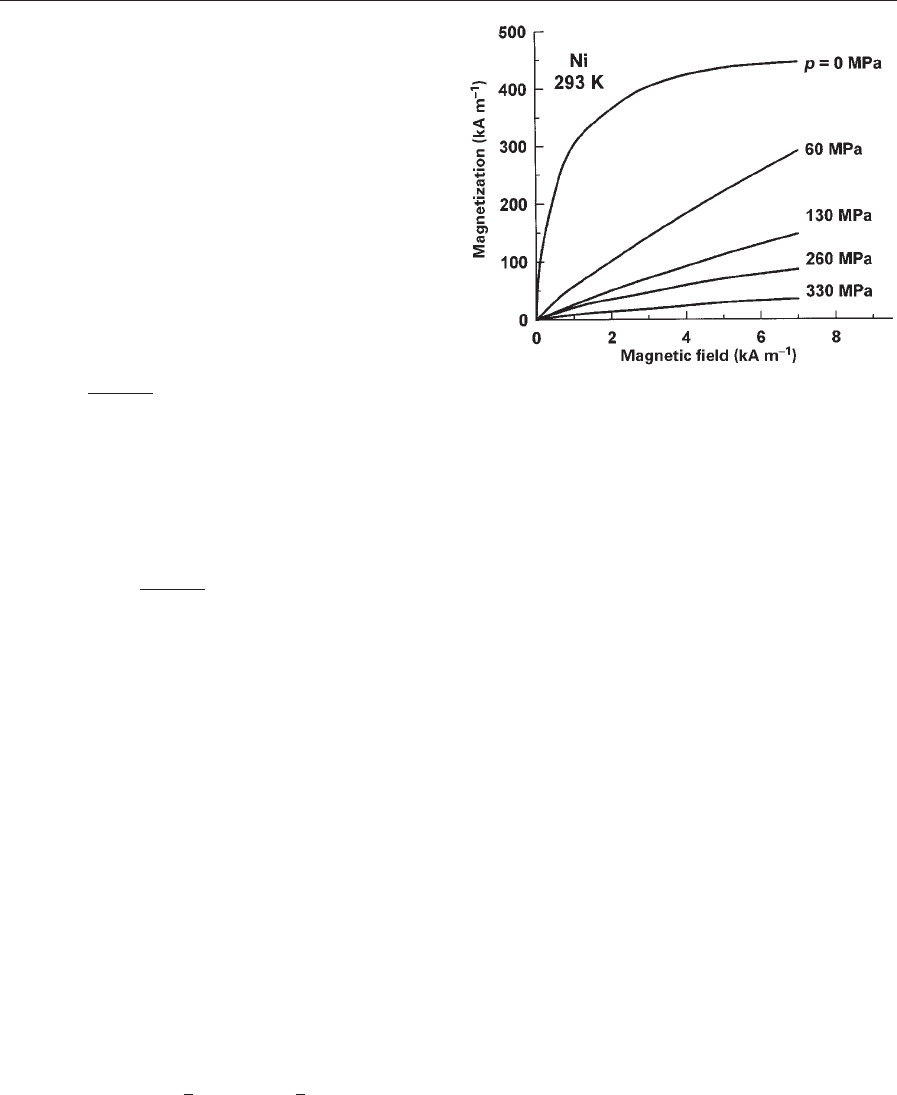

3. Villari Effect

The magnetoelastic effect which is the reverse of the

Joule MS, i.e., dependence of the magnetization

curve on the mechanical stress was extensively stud-

ied by Villari in 1865. The magnetization curves

shown in Fig. 6 illustrate the effect of tensile stress in

nickel in the longitudinal geometry (magnetization is

measured along the tensile stress). At high values of

stress, the room-temperature magnetization curves

are completely determined by the uniaxial magnetic

anisotropy induced by tensile stresses. For an iso-

tropic ferromagnet, the magnetoelastic anisotropy

energy can be expressed by (Belov 1987):

W

me

¼

3

2

l

s

s cos

2

f

1

3

ð10Þ

where s is a stress, and f represents the angle be-

tween M and s. When the stress is positive and the

MS is negative (the case of nickel in Fig. 6), W

me

has

a minimum at f ¼p/2, i.e., the induced easy mag-

netization axis lies perpendicular to s. The direction

of s becomes the hard magnetization axis and there-

fore the saturation field increases with the stress

(Fig. 6). When l

s

s40, the easy magnetization axis is

along s, and the stress makes it easier to reach the

saturation of magnetization.

4. Magnetoelastic Contribution to the Magnetic

Anisotropy

Even without any external or internal stresses the

magnetoelastic coupling modifies the energy of mag-

netic anisotropy of a crystal. Besides the magneto-

crystalline anisotropy, a magnetoelastic anisotropy of

the same symmetry appears, which causes additive

contributions to the magnetic anisotropy constants.

For a cubic crystal, the magnetoelastic contribution

to the first anisotropy constant, K

1

, can be written as

(Belov et al. 1983):

DK

1

¼ð9=4Þ½ðc

11

c

12

Þl

2

100

2c

44

l

2

111

ð11Þ

where c

ij

are the elastic constants. The magnetoelastic

contribution is responsible for the change of the sign

of K

1

in nickel near 480K. In rare earth and actinide

compounds the magnetoelastic contribution DK

1

is

comparable with K

1

and must be taken into account

in the description of the magnetization curves and

spin-reorientation phase transitions.

5. DE Effect

The elastic properties of a ferromagnet may be per-

turbed by the magnetoelastic coupling. The magnetic

Figure 6

Room-temperature magnetization curves of nickel

under varying tensile stresses.

771

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

field dependence of the elastic modulus, E (DE effect),

was discovered by Guillemin in 1846. The DE effect

is usually described in terms of the ratio DE/E ¼

(E

0

E)/E, where E is the experimentally observed

value and E

0

is the value for the case when the elastic

stress does not cause magnetization rotation and do-

main walls movement. In a low-anisotropy material it

occurs practically at the field of technical saturation

but generally E-E

0

for H-N . In ferromagnets,

DE40 and is independent of the sign of l and s .A

theory of the DE effect for isotropic ferromagnets

gives the following relations for the limit of very low

(LF) and very high (HF) magnetic fields, respectively

(du Tremolet de Lacheisserie 1993):

DE

E

LF

¼

9

5

w

i

l

s

E

2

0

m

0

M

2

s

;

DE

E

HF

¼

9

4

l

2

s

E

0

MH

sin

2

2y ð12Þ

where y is the angle between the internal magnetic

field and the axis of measurement of E. A very large

DE effect may be expected at low H in materials ex-

hibiting a large initial susceptibility, w

i

, and a large l.

Among the giant MS materials, the largest DE effects

are exhibited by TbFe

2

(up to 0.6) and the low-an-

isotropy alloy Tb

0.3

Dy

0.7

Fe

2

(up to 1.6). The same

value of DE/E ¼1.6 is observed also in UFe

2

. For the

high-magnetostrictive Metglass Fe

81

B

13.5

Si

3.5

C

2

, DE/

E ¼15 (Belov et al. 1983 and references therein).

6. Direct and Inverse W iedemann Effects

When a thin ferromagnetic rod is simultaneously

magnetized by a longitudinal field, H

8

, and by a cir-

cular field, H

>

, generated by an electrical current

flowing along the sample, the resulting helicoidal

magnetic field causes twisting of the rod (the direct

Wiedemann effect). For an isotropic wire at a suffi-

ciently low current density, j, and a sufficiently high

magnetizing field (H

>

5H

8

) the twist per unit length,

x, is given by (du Tremolet de Lacheisserie 1993):

x ¼

3

2

l

>

H

8

j ð13Þ

Since, x, j, and H

8

can be measured with high accu-

racy, the Wiedemann effect is a valuable method of

determination of l

s

in soft ferromagnets.

There are two inverse Wiedemann effects:

(i) The change of the longitudinal magnetization,

dM

z

, and the appearance of a circular magnetization,

M

F

, in a long ferromagnetic rod magnetized along its

length when subjected to a mechanical torque; a

voltage appears between the ends of the rod due to a

longitudinal electric field associated with the change

of the circular magnetization (the Matteuchi effect).

(ii) The change of the circular magnetization,

dM

F

, and the appearance of a longitudinal magnet-

ization, M

z

, in a long ferromagnetic rod where an

electric current passes when the rod is submitted to a

mechanical torque.

7. Linear Magnetostriction. Piezomagnetism

Most ferromagnets and antiferromagnets exhibit a

quadratic field dependence of MS in low magnetic

fields. However, in low-symmetry materials the ther-

modynamic potential can contain nonzero terms lin-

early dependent on the field and on a component of

the elastic stress tensor. For 66 magnetic symmetry

classes (including 35 of 59 AF classes) a strain var-

ying linearly with applied magnetic field is possible

(Birrs 1964). In fact, a linear MS is rarely observed

since it is usually masked by much stronger quadratic

effects. The odd linear magnetostrain was observed in

AF hematite, a-Fe

2

O

3

, as well as in the orthoferrites

YFeO

3

and YCrO

3

in the region of spin-reorientation

transitions (du Tremolet de Lacheisserie 1993 and

references therein).

An inverse effect to the linear MS (piezomagnetism)

is the appearance of a spontaneous magnetization

under external stress. Piezomagnetism is observed in

CoF

2

, MnF

2

, a-Fe

2

O

3

, and FeCO

3

(du Tremolet de

Lacheisserie 1993 and references therein).

8. Applications of Magnetoelast icity

Application of isotropic magnetoelastic coupling is

limited mainly to the Invar alloys for cases where a

low thermal expansion coefficient of the metal is re-

quired (e.g., in glass–metal assemblies). Elinvar alloys

exhibiting the DE effect are employed whenever the

elastic properties must be stable over some temper-

ature interval (e.g., a clock spring).

Joule MS is widely used both in static and dynamic

devices. The static MS allows the construction of

linear actuators offering sufficiently large displace-

ments (20–200mm) and large forces (500–5000 N) at

low voltage. Linear actuators are used in microposi-

tioning tools or for damping structures, as well as for

components of more complex actuators.

Spring-type magnetostrictive actuators employing

the direct Wiedemann effect have been designed for

positioning optical units and mechanical parts up to

5Kg: the pieces may be oriented with an accuracy of

10

5

degree in a frequency range up to 70Hz.

A magnetic material in an alternating magnetic

field undergoes mechanical oscillations due to the

MS. A well-known result of such oscillations is the

noise of electric power transformers. Therefore, for

this and related purposes, the MS should be reduced

to as low as possible (zero-MS materials include

cobalt-rich amorphous alloys). However, if the MS

core has appropriate dimensions, resonance oscilla-

tions can appear. Some magnetoelastic materials with

sharp resonance (high Q-factor) are used in frequency

stabilizers and filters.

772

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

An important area of technical application of mag-

netostrictive materials is in high-power transducers

both for acoustic (loudspeakers, sonars, echo-sound-

ers, defectoscopes, etc.) and for mechanical (welding,

sealing, cleaning, cutting, etc.) purposes at typical

frequencies below 50 kHz. For these devices the most

important property of the material is not the MS, l,

but the magnetostrictivity, @l/@H. A certain ampli-

tude of mechanical oscillation should be reached in as

small a magnetic field interval as possible. The rel-

evant parameters are the MS coefficient:

h ¼

@s

@B

e

¼

E

m

@l

@H

ð14Þ

and the coefficient of sensitivity of a magnetostrictor

as an acoustic receiver:

d ¼

@B

@s

H

ð15Þ

where H and B are the magnetic field and the mag-

netic induction, respectively, s is the mechanical

stress, e is the relative strain, E is the elastic modulus,

and m is the permeability at constant induction (Belov

et al. 1983).

The transformation of the magnetic energy, U

magn

,

into the elastic energy, U

elast

, is characterized by the

magnetomechanical coupling factor of the sample,

k ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ðU

elast

=U

magn

Þ

p

, showing the fraction of U

magn

which can be converted to U

elast

. The coupling factor

is conventionally obtained by measuring the complex

impedance of a coil containing the magnetostrictive

material. Generally, it depends on the shape of the

sample. In the practically important case when the

mechanical motion is parallel to the exciting field, k is

specified as k

33

, a geometry-independent coupling

factor characterizing the material (Clark 1980).

In order to select the maximum @l/@H in the field

dependence of l, a static bias magnetic field is usually

applied to the MS core. The elastic energy density can

be increased using prestress of a magnetostrictive rod.

The best reported magnetostrictive transducers allow

one to generate a 3kW acoustic power. For a review

of devices based on materials with giant MS, see

Claeyssen et al. (1997).

The magnetoelastic characteristics of some materi-

als are presented in Table 2 (adapted from Clark

1980, Tremolet de Lacheisserie 1993, Golyamina

1992). Nickel is a traditional material widely used

in magnetomechanical converters. In order to im-

prove the @l/@H and k

33

values, alloying components

that reduce the magnetocrystalline anisotropy can be

added (the alloy 96Ni4Co with compensated anisot-

ropy possesses a k

33

factor as high as 0.6). Among the

magnetostrictive alloys based on iron and cobalt, the

best parameters are shown by the alloy 49Co49Fe2V.

Owing to its high T

C

, the magnetoelastic properties of

this alloy are stable over a wide temperature interval.

In high-frequency magnetomechanical converters the

ferrites are used as core materials owing to their high

electrical resistance. The nickel ferrite NiFe

2

O

4

has

relatively high l

s

but k

33

is small. The k

33

value and

Q-factor increase with the substitution of copper,

zinc, and cobalt for nickel. An outstanding value of

k

33

¼0.97 has been obtained on the field-annealed

Metglas Fe

81

B

13.5

Si

3.5

C

2

in a polarizing magnetic

field of 50Am

1

.

Rare earth intermetallic compounds possess giant

MS caused by rare earth ions. The largest room-tem-

perature l

s

is found in TbFe

2

. However, @l/@H is low

owing to a high magnetocrystalline anisotropy and

the l

s

value is achieved only in fields above 2T. The

value of @l/@H can be substantially improved using

quasibinary compositions (Tb

1x

Dy

x

)Fe

2

at x B0.7

(Terfenol-D) owing to the compensation of the an-

isotropy constant K

1

. This leads to an increase of k

33

despite a certain decrease of l

s

(Table 2).

See also: Magnetic Systems: External Pressure-

induced Phenomena; Invar Materials: Phenomena;

Metamagnetism: Itinerant Electrons; Itinerant

Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromagnetism);

Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism; Magne-

tostrictive Materials; Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale

Heterogeneous Materials

Table 2

Saturation magnetostriction, l

s

, magnetomechanical coupling factor, k

33

, Q-factor, and Curie temperature, T

C

, for

some magnetostriction materials.

Material l

s

( 10

6

) k

33

Q-factor T

C

(1C)

Ni 37 0.25–0.31 700 360

96Ni4Co 31 0.6 410

87Fe13Al þ 40 0.32 400 500

49Co49Fe2V þ 70 0.2–0.4 600 980

NiFe

2

O

4

þ Cu,Co 26 0.25 2000 590

Fe

81

B

13.5

Si

3.5

C

2

Metglas þ 30 0.97 370

TbFe

2

1750 0.35 100 425

Tb

0.27

Dy

0.73

Fe

2

1000–1500 0.6–0.75 50–200 380

773

Magnetoelastic Phenomena

Bibliography

Andreev A V 1995 In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of

Magnetic Materials. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 8, pp. 59–187

Andreev A V, Bartashevich M I, Goto T 1995 Magnetostriction

of UNiGa at metamagnetic transition. J. Alloys Compounds

219, 267–70

Belov K P 1987 Magnetostriction Phenomena and Their Tech-

nical Applications. Nauka, Moscow (in Russian)

Belov K P, Kataev G A, Levitin R Z, Nikitin S A, Sokolov V I

1983 Giant magnetostriction. Sov. Phys. Uspekhi 26, 518–42

Birrs R R 1964 In: Wohlfarth E P (ed.) Selected Topics of Solid

State Physics. North Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 8

Callen E R, Callen H B 1963 Static magnetoelastic coupling in

cubic crystals. Phys. Rev. 129, 578–93

Claeyssen F, Lhermet N, Le Letty R, Bouchillioux P 1997 Ac-

tuators, transducers and motors based on giant magnetos-

trictive materials. J. Alloys Compounds 258, 61–73

Clark A E 1980 In: Wohlfarth E P (ed.) Ferromagnetic Mate-

rials. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 1, pp. 531–89

Givord D, Lemaire R, James W J, Moreau J M, Shah J S 1971

Magnetic behavior of rare-earth iron-rich intermetallic com-

pounds. IEEE Trans. Magn. MAG-7, 657–9

Golyamina I S 1992 In: Prokhorov A M (ed.) Physical Ency-

clopedia. Big Russian Encyclopedia, Moscow, Vol. 3, pp. 8–9

(in Russian)

Kido G, Nakagawa Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nishihara Y 1988 Forced

magnetovolume effects in Sc

1x

Ti

x

Fe

2

at the ferromagnetic

to ferromagnetic transition. J. Phys. 49, C8-251–2

Levitin R Z, Ponomarev B K 1966 Magnetostriction of the

metamagnetic FeRh alloy. Soviet Phys. JETP. 50, 1478–83

Nakamura Y 1983 Magnetovolume effects in Laves phase

intermetallic compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 31–34,

829–34

Palstra T T M, Nieuwenhuys G J, Mydosh J A, Buschow K H J

1985 Mictomagnetic, ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic

transitions in La(Fe

x

Al

1x

)

13

intermetallic compounds. Phys.

Rev. B 31, 4622–32

du Tremolet de Lacheisserie E 1993 Magnetostriction: Theory

and Applications of Magnetoelasticity. CRC Press, Boca

Raton, FL

A. V. Andreev

Institute of Physics, Prague, Czech Republic

N. V. Mushnikov

Institute of Metal Physics, Ekaterinburg, Russia

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale

Heterogeneous Materials

When a material becomes magnetic, the magnetoelas-

tic coupling causes a change in volume, the volume

magnetostriction, and anisotropic changes in linear

dimensions, the Joule magnetostriction. The magnetic

order, and thus the deformation, can be induced

either by a temperature variation (spontaneous mag-

netostriction) or by application of a magnetic field

(forced magnetostriction). The magnetostriction varies

from nearly 1% in rare-earth-based intermetallic

compounds to almost zero for iron-based amor-

phous and nanocrystalline alloys (see Magnetostrictive

Materials).

The local properties of nanoscale heterogeneous

magnetic systems do vary in the scale of nanometers,

for amorphous materials even on an atomic scale (see

Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials). Hetero-

geneous materials may exhibit surface (interface)

magnetic anisotropy and magnetostriction, negligible

in bulk material. For many applications, magnetos-

trictive thin films are of special interest, because

cost-effective mass production is possible. In micro-

electromechanical systems (MEMSs; see Microme-

chanical Systems, Principles of ), thin films exhibiting

giant magnetostriction (GMS; see Thin Films Giant

Magnetoresistive), preferably at low fields, are ap-

plied as microactuator elements like cantilevers

(see Fig. 1) or membranes, since they combine high-

energy output, high-frequency, and remote-control

operation. Here, good performers are thin films of

rare-earth–transition metal (RT) intermetallic com-

pounds. More recently, attention is also focused on

the magnetostrictive properties of perovskite man-

ganites and cobaltates, which are known to exhibit

large changes in resistivity upon magnetization

(colossal magnetoresistance (CMR); see Transition

Metal Oxides: Magnetism).

In order to reduce the number of explicit refer-

ences, for many details we only indicate where ref-

erences can be found in Duc and Brommer (2002).

1. Magnetoelastic Effects

The free energy of a magnetic substance is the sum of

the magnetostatic energy and the ‘‘internal’’ free en-

ergy. The magnetostatic energy originates from the

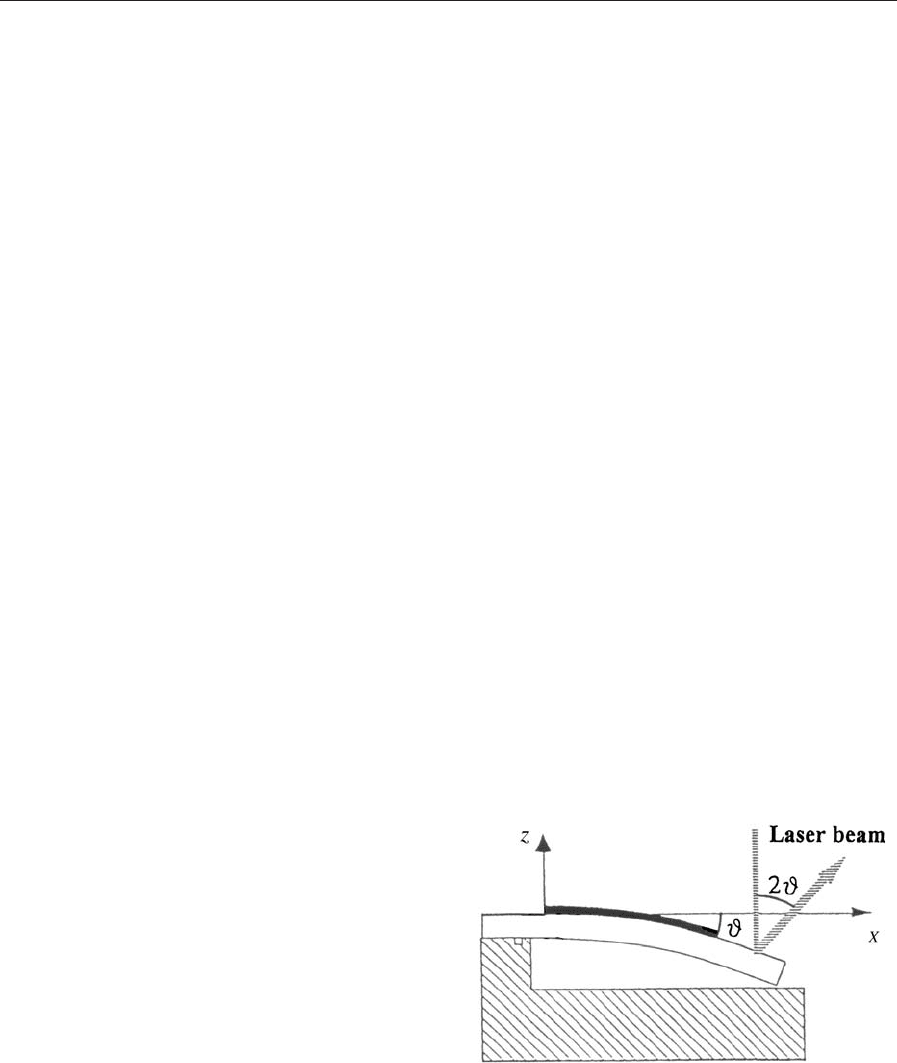

Figure 1

A typical magnetostrictive cantilever consists of a thin

film deposited on a suitable substrate, which is clamped

on the sample holder. The deformation caused by

application of a magnetic field can be determined by

measuring the deflection of a laser beam.

774

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Heterogeneous Materials

(long-range) dipolar interactions, giving rise to de-

magnetizing fields and shape anisotropy. The con-

current deformations depend on the geometry of the

sample (hence the name form effect), but are small

(p10

6

), and often negligible. The ‘‘internal’’ free

energy is expanded in the symmetrized strains e

xx

, e

yy

,

e

zz

, e

xy

, e

yz

, e

xz

, and the direction cosines of the mag-

netization a

i

(i ¼1, 2, 3, corresponding to Cartesian

coordinates x, y, z, respectively). The free energy is

invariant under symmetry transformations, and thus

can best be expressed in linear combinations of the

strains (e.g., e ¼ e

xx

þ e

yy

þ e

zz

) and polynomials

(such as a

2

1

þ a

2

2

þ a

2

3

¼ 1, a

1

a

2

or ða

2

3

1

3

Þ), which

span invariant irreducible subspaces. The strain e

mentioned above spans a one-dimensional invariant

subspace. For an n-dimensional irreducible subspace

g, spanned by strains fe

g

j

g or polynomials fh

g;m

j

ðaÞg of

degree m, with j ¼ 1; y; n, a fundamental group-the-

oretical theorem states that the only (second-order)

invariants are

P

j

ðe

g

j

Þ

2

;

P

j

ðh

g;m

j

Þ

2

, and the bilinear

magnetoelastic coupling terms

P

j

e

g

j

h

g;m

j

ðaÞ: The

magnetostrictive strains follow from the minimiza-

tion of the free energy part

1

2

C

g

P

j

ðe

g

j

Þ

2

þB

g;m

P

j

e

g

j

h

g;m

j

ðaÞ, yielding e

g

j

¼ðB

g;m

=C

g

Þh

g;m

j

ðaÞ, gov-

erned by the (first-order) ‘‘coefficient of magneto-

striction’’ l

g;m

¼ðB

g;m

=C

g

Þ.

As an example, we decompose the free-energy den-

sity of an isotropic material as F ¼ F

a

þ F

g

:

F

a

¼ð1=2ÞC

a

e

2

=3 þ B

a;0

e=3 ð1aÞ

F

g

¼ð1=2ÞC

g

ð3=2Þðe

zz

e=3Þ

2

þð1=2Þðe

xx

e

yy

Þ

2

hi

þ B

g;2

½ð3=2Þðe

zz

e=3Þða

2

3

1=3Þ

þð1=2Þðe

xx

e

yy

Þða

2

1

a

2

2

Þ ð1bÞ

Minimizing the free energy results in the volume

magnetostriction e ¼ l

a;0

¼B

a;0

=C

a

, and the Joule

magnetostriction components ðe

zz

e=3Þ¼ l

g;2

ða

2

3

1=3Þ, and ðe

xx

e

yy

Þ¼l

g;2

ða

2

1

a

2

2

Þ, with l

g;2

¼

B

g;2

=C

g

(equivalently, for instance, e

xy

¼ l

g;2

a

1

a

2

(cycl.)). Inserting these results in the general expres-

sion for the linear expansion, measured in the direc-

tion b ¼ðb

1

; b

2

; b

3

Þ

Dc=c ¼ e

xx

b

2

1

þ 2e

xy

b

1

b

2

þ cycl: ð2Þ

yields

Dc=c ¼l

a;0

=3 þ l

g;2

½fða

2

3

l=3Þðb

2

3

1=3Þþcycl:g

þf2a

1

a

2

b

1

b

2

þ cycl:g ð3Þ

From this expression, one defines the ‘‘saturated’’

relative change of length measured along the field

direction (common to the magnetization direction) as

l

s

¼ðDc=c Þ

sat

8

l

a;0

=3 ¼ 2l

g;2

=3: The relative change

in the plane perpendicular to the field would be

1

2

l

s

¼ðDc=c Þ

sat

>

l

a;0

=3: In practice, it is necessary

to measure in two perpendicular directions and de-

termine 3l

s

=2 ¼ l

g;2

¼½ðDc=cÞ

sat

8

ðDc=cÞ

sat

>

.

For uniaxial symmetry, the six strain components

are subdivided into two one-dimensional subsets (in-

dicated by the superscript a, and subscripts 1 and 2

for the volume dilatation and the axial deformation,

respectively), and two different two-dimensional sub-

sets, indicated by g for in-plane deformations, and by

e for ‘‘skew’’ deformations. In this case, the magne-

tostriction can be expressed as

Dc=c ¼l

a;0

1

=3 þ l

a;0

2

ðb

2

3

1=3Þ

þ½l

a;2

1

=3 þð3=2Þl

a;2

2

ðb

2

3

1=3Þða

2

3

1=3Þ

þ l

g;2

½ð1=2Þðb

2

1

b

2

2

Þða

2

1

a

2

2

Þþ2a

1

a

2

b

1

b

2

þ 2l

e;2

ða

3

a

2

b

3

b

2

þ a

3

a

1

b

3

b

1

Þð4Þ

Notice here the uniaxial deformation, l

a;0

2

, independ-

ent of the direction of the magnetization, and the

contribution to the volume magnetostriction, l

a;2

1

,

which does depend on the magnetization direction

(see fig. 3 in Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 101).

At the surface of an isotropic material the symme-

try is reduced from isotropic to uniaxial. The con-

current increase of the necessary number of

coefficients (compare Eqns. (4) and (3)) is an exam-

ple of quite a general rule. This subject is worked out

in detail in, for instance, the textbooks written by Du

Tre

´

molet de Lacheisserie (1993, 1999).

Most theoretical models for surface anisotropy and

magnetostriction are rather phenomenological, based

on lower coordination numbers and ‘‘missing’’ pair

interactions at the surface. Ab initio calculations were

reported by Freeman’s group (Duc and Brommer

2002, p. 105). Direct experimental evidence of surface

magnetoelastic coupling was provided by measuring

the strain dependence of the surface magnetization as

determined by secondary-electron spin polarization

spectroscopy (Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 112).

Since the surface effects contribute ‘‘per unit sur-

face area,’’ one defines, for a layer of thickness t,

effective parameters such that B

eff

equals B

bulk

þ

2B

surf

=t. Here, the factor 2 is put in, because a layer

has two surfaces. In practice, this simple 1/t depend-

ence works satisfactorily. For nanocrystallites, both

the volume fraction and the ‘‘volume-to-surface ra-

tio’’ of the crystallites (i.e., their radii) must be taken

into account.

For higher-order coupling terms, i.e., nonlinear in

the strains, analogous symmetry considerations lead

to the correct ‘‘group-theoretical’’ invariant magne-

toelastic energy contributions. Sander (1999) has

shown that for epitaxially grown films, second-order

magnetoelastic coupling parameters must be taken

into account because of the large ‘‘epitaxial’’ strains

due to the mismatch between substrate and film (Duc

and Brommer 2002, p. 105)

775

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Heterogeneous Materials

2. Nanoscale Heterogeneous Structures

2.1 Bulk Material (Ribbons, Thick Films)

Research on bulk giant magnetostrictive materials

has been focused on iron-based rare-earth alloys, be-

cause they combine a high rare-earth concentration,

thus a high magnetostriction, with a high-ordering

temperature. The corresponding crystalline RCo

2

compounds are not particularly interesting for appli-

cations, because of their lower Curie temperatures:

they do exhibit huge magnetostriction, but at low

temperatures only.

A high room-temperature magnetostriction was

found in Terfenol (polycrystalline TbFe

2

: Ter for

Tb, fe for Fe, nol for Naval Ordnance Laboratory,

where it was developed). Terfenol-D (D for Dy:

Tb

x

Dy

1x

Fe

2

, where xE0:3) exhibits a reduced mag-

netic anisotropy, and thus lower (but still rather high)

coercivities, together with a large magnetostriction:

l

s

E1500 10

6

(T

C

E650 K) (Duc and Brommer

2002, p. 94).

In general, various nanocrystalline structures can

be obtained by suitable heat treatments: quenching,

(magnetic) annealing. Moreover, the (re)crystalliza-

tion process can be influenced by additives such as

Nb, Mo, Zr, etc. The size of the nanocrystallites de-

termines the surface-to-volume ratio. Combining sur-

face effects and the bulk properties, one can, for

instance, achieve low anisotropy (optimal magnetic

softness) or minimal magnetostriction (transformers).

2.2 Thin Films

Thin films are often deposited (by sputtering) as an

amorphous layer on a substrate. Again, suitable heat

treatments can be applied to enhance the properties

(e.g., in-plane or perpendicular anisotropy). By con-

trolled recrystallization of Fe-rich amorphous alloys,

a material consisting of nanocrystalline grains em-

bedded in an amorphous matrix can be formed (see

Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials). The ef-

fective magnetostriction combines the negative con-

tribution of the crystalline phase with the positive

contribution of the amorphous phase, whereas in

many cases also a surface contribution must be taken

into account (see, e.g., the work of Herzer, Szymczak,

S

´

lawska-Waniewska, Z

´

uberek, Gutierez, and oth-

ers—seeDuc and Brommer 2002, p. 168 ff ).

In amorphous Fe-based thin films, the variation

in the Fe–Fe interatomic distance leads to large var-

iations (different signs) of the Fe–Fe exchange inter-

actions, and thus to frustration and freezing of the

Fe-moments in different directions: asperomagnetism

ðM

s

40Þ or speromagnetism ðM

s

¼ 0Þ. Because of

the concurrent variation in the local easy axis for the

rare-earth moment, in amorphous (Tb,Fe) both the

Tb and the Fe subsystem exhibit asperomagnetism

(Fig. 2), with reduced subsystem magnetization, and

hence magnetostriction. The Curie temperature is

lower too. In a-(Tb,Co) only the Tb-subsystem

exhibits asperomagnetism (Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 116), whereas the Curie temperature is raised. Be-

cause of the important role of the ‘‘Laboratoire Louis

Ne

´

el’’ in their development, Duc (Duc and Brommer

2002, p. 94) proposed to refer to the a-(Tb,Co) alloys,

with composition near TbCo

2

, as ‘‘a-TerCoNe

´

el,’’

by an obvious analogy to TerFeNol, to amorphous

Tb-(Fe,Co)

2

thin film ðl

s

E1020 10

6

Þ as ‘‘a-Terf-

econe

´

el,’’ and, adding Dy, to ‘‘a-Terfecone

´

el-D.’’ In

Hanoi, amorphous Tb(Fe

0.55

Co

0.45

)

1.5

, to be named

‘‘a-Terfecohan,’’ was developed and found to exhibit

already a large magnetostriction ðl

8

E340 10

6

Þ at

m

0

H ¼ 20 mT (Fig. 3).

2.3 Sandwich Structures

Sandwich films of the type RT/R

0

T/RT consist of

layers with typical thicknesses of 100 nm. Because

magnetization or anisotropy differ from one layer to

Figure 2

Sperimagnetic structure of amorphous Tb–Fe and Tb–

Co.

Figure 3

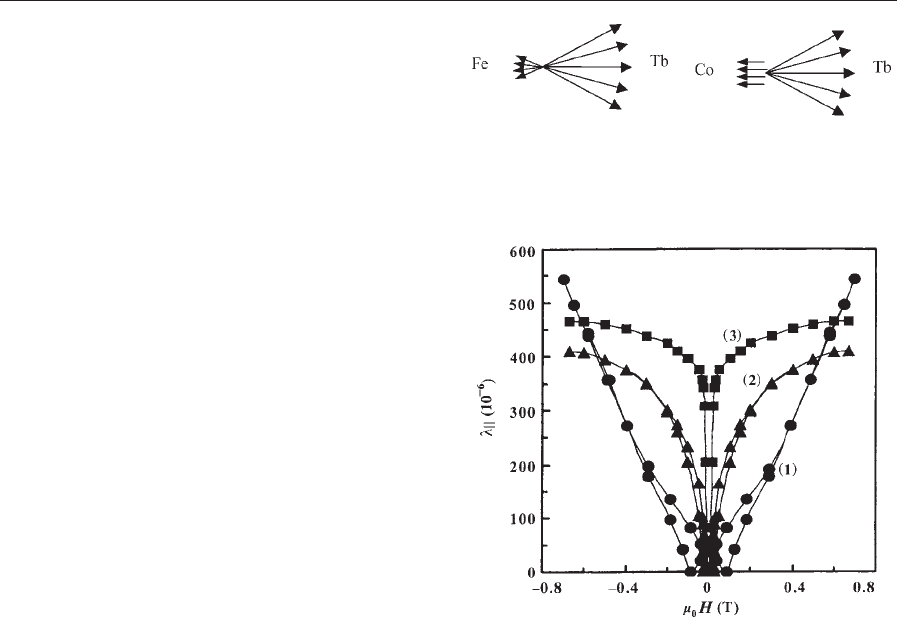

Parallel magnetostrictive hysteresis loops for

Tb(Fe

0.55

Co

0.45

)

1.5

films: (1) as-deposited film, (2) after

annealing at 350 1C and (3) at 450 1C (after Duc et al.

2000).

776

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Heterogeneous Materials

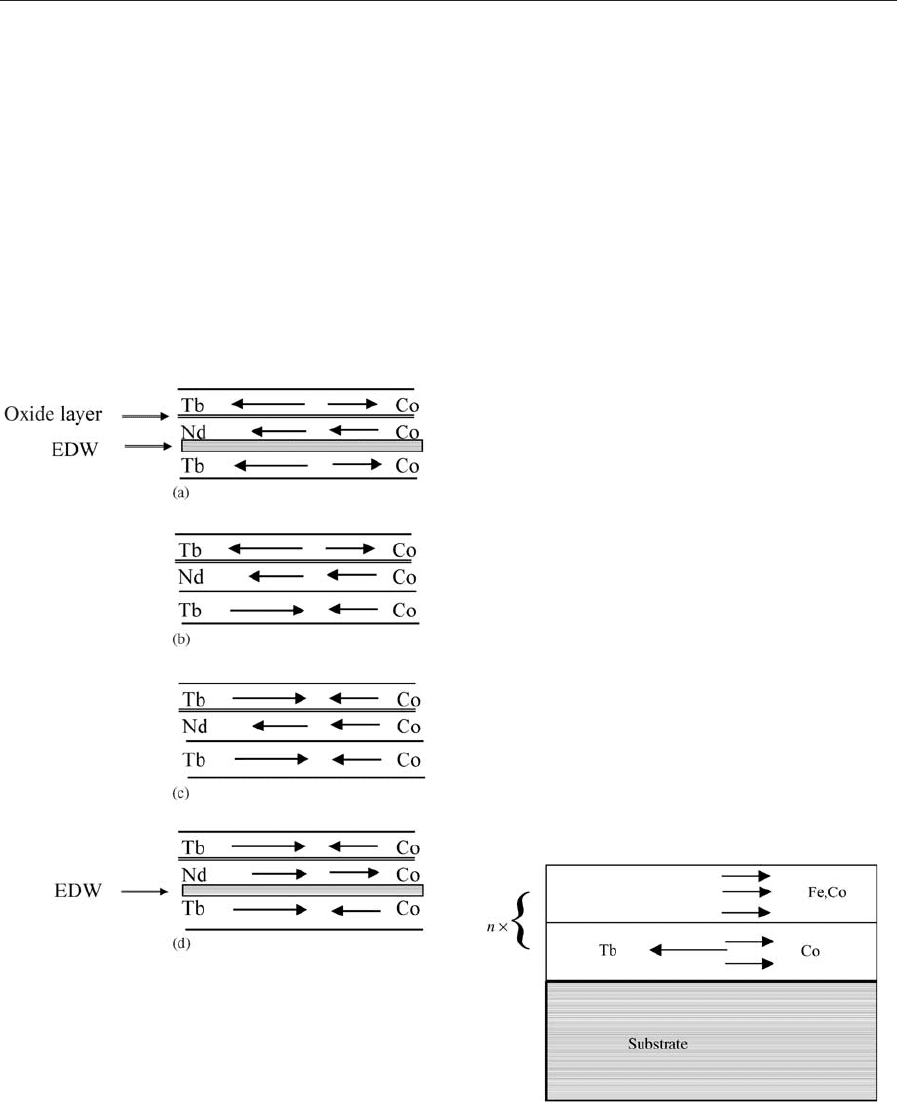

the next, magnetization reversal occurs at a different

field for each layer. An extended domain wall (EDW)

can be formed at an interface, affecting (reducing)

appreciably the magnetostriction because of its rela-

tively large volume. The exchange coupling of the

layers can be suppressed by fabricating a thin oxide

layer at the interface. The observed jumps in the

magnetization curve of a TbCo/NdCo/TbCo sand-

wich (Givord et al.—see Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 165), and the corresponding variations of the

observed magnetostriction confirm the process de-

picted in Fig. 4.

EDW formation has also been observed in TbFe/

FeCoBSi multilayers (Quandt and Ludwig—see Duc

and Brommer 2002, p. 165) with layer thickness

above 20–25 nm (see below).

2.4 Multilayers

(a) Spacer layers

To reduce coercivity significantly in R–Fe alloys, the

crystalline-grain size is desirable to be smaller than

the Bloch wall width, i.e., below 5 nm. One can limit

the grain growth by depositing, for instance, Nb-

layers (0.25 nm) as spacers between 5 nm TbDy-

Fe þZr (Fisher and Winzek—see Duc and Brommer

2002, p. 139). Suitable heat treatment now results in a

parallel magnetostriction of 520 10

6

, whereas the

coercive fields stay distinctively below 100 mT.

Analogous structures may be formed in multilayers

when the sharp interfaces are broadened by interdif-

fusion (Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 151 ff).

Notice, that in some cases multilayers (or multi-

threaded material) can be produced by repeatedly

cold rolling or extrusion (Hai et al. 2003).

(b) Magnetostrictive spring magnet type multilayers

(MSMMs)

Magnetostrictive, spring magnet type, or rather ex-

change coupled, multilayers (Fig. 5) combine the

large magnetostriction of, for example, a-Tb-(Fe,Co),

with the desired soft-magnetic properties and the high

magnetization of, for example, (nano)crystalline

(Fe,Co). A huge magnetostrictive susceptibility

dl

8

=dB ¼ 13 10

6

T

1

was reported for {a-Ter-

fecohan/(nano)YFeCo} multilayers (Duc and Brom-

mer 2002, p. 152). The layers must be thin enough

(1–20 nm) to prevent EDW formation. Then, the

multilayer is one magnetic unit in which the 3d23d

exchange interactions ensure parallel coupling of the

transition metal moments, antiferromagnetically cou-

pled with the Tb-moments (Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 140 ff ).

For multilayers, the effective magnetostriction as a

function of the thickness t of the magnetic layers has

been studied extensively (Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 155 ff ). As mentioned above, in general the effective

Figure 4

Occurrence of extended domain walls in a TbCo/NdCo/

TbCo sandwich film during the magnetization process.

A well-defined easy magnetization direction was

introduced by annealing in a magnetic field. (a) High

negative field: an EDW is formed at the coupling

interface to match the antiparallel Co moments; (b) low

negative field: the EDW is destroyed when the Co

moments are parallel; (c) low positive field: the

‘‘uncoupled layer’’ is switched first; and (d) high positive

field: the EDW is necessary again.

Figure 5

Schematic view of an exchange coupled MSMM

(Tb,Co)/(Fe,Co). Layer thickness is 1–20 nm. The

repetition number n is of the order of 100.

777

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Heterogeneous Materials

magnetostriction depends linearly on 1/t, i.e.,

l

eff

¼ l

bulk

þ 2l

surf

=t.

2.5 Superlattices

Magnetic rare-earth superlattices R/M (M ¼Y, Lu)

are produced by depositing a distinct number of

atomic planes per layer. As an example, a {Ho

31

/

Lu

19

}

50

superlattice has 50 layers consisting of 31 Ho

and 19 Lu planes (alternatively: [Ho

31

/Lu

19

] 50).

Remarkable features in these artificial structures are:

(i) helical magnetic order (spin density wave) is found

to propagate through the (very thin) nonmagnetic

layers; (ii) due to epitaxial strains and strains caused

by mismatching subsequent layers, the magneto-elas-

tic coupling ðB

g

Þ in a superlattice layer may be dif-

ferent from that in the bulk; and (iii) large surface

effects are observed (Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 159

ff). A magnetic-phase diagram was constructed for

{Ho

6

Y

6

}

100

consisting of a ferromagnetic, a fan, and

a helical structure. For {Ho

n

Lu

15

}

50

superlattices, the

relationship B

g

¼ðB

g

vol

þ DeÞf

1

ðmÞþ2t

1

Ho

B

g

surf

f

2

ðmÞ

appears to describe the observed phenomena satis-

factorily as a function of the Ho layer thickness, t

Ho

,

and of the reduced magnetization, m. Here f

1

(m)is

the general function, derived by Callen and Callen

(see Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 161) for a single-ion

crystal field contribution, expressing the temperature

dependence of the magnetostriction through the tem-

perature dependence of m. f

2

(m) is taken to be pro-

portional to m

4

at low temperatures and to m

2

at high

temperatures. B

g

vol

ð¼ 0:275 GPaÞ has about the same

value as for bulk Ho. B

g

surf

=ðc=2Þ ( ¼7.0 GPa, where

c is the c-axis parameter of Ho) represents a contri-

bution of opposite sign, large for a thin Ho layer.

2.6 Granular Composites

The recrystallized Fe-rich amorphous alloys, com-

posed of crystalline grains embedded in a residual

amorphous matrix, belong to a wide class of heter-

ogeneous structures, ranging from organometallic

complexes or metallic clusters deposited on graphite

or built-in in polymers on a molecular scale, up to

composites consisting of microscale grains embedded

either in a metallic binder or in some resin or polymer

(see, e.g., Gubin, Kosharov, Herbst, Pinkerton,

Duenas, Carman—see Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 168 ff ). These materials exhibit novel phenomena

such as superparamagnetism, giant magnetoresist-

ance, and giant magnetic coercivity (Chien, Her-

nando, Duc—see Duc and Brommer (2002)). On the

one hand, the (nano)crystalline fraction can be ma-

nipulated in such a way that zero magnetostriction

results (useful for core material), for example, in

Fe

90

Hf

7

B

3

(Chiriac—see Duc and Brommer (2002))

and Fe

85.5

Zr

2

Nb

4

B

8.5

ribbons (Makino—see Duc and

Brommer (2002)), in as-deposited Fe–Al–O and

(Co

0.94

Fe

0.06

)–Al–O films, and, after annealing at

300 1C, also for (Co

0.92

Fe

0.08

)–Al–O films (Oh-

numa—see Duc and Brommer (2002)). On the other

hand, composites containing (microscale) Terfenol-D

grains in a nonmetallic binder (epoxy) may optimally

have a magnetostrictive response comparable to that

of Terfenol-D itself (Duenas and Carman, Arm-

strong—see Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 173). Such

composites are durable and are easily machined into

complex shapes.

2.7 Perovskite Manganites and Cobaltates

Huge magnetostriction has been found in perovskite

manganites R

1x

A

x

MnO

3

(R: trivalent rare earth; A:

divalent cation), cobaltates R

1x

A

x

CoO

3

, and some

related (doped) layered manganese oxides with for-

mula ðR

1y

A

y

Þ

nþ1

Mn

n

O

3nþ1

(in particular the highly

anisotropic, almost two-dimensional, n ¼ 2 mem-

bers), exhibiting CMR. Thin films of these ceramics

can be produced by (pulsed) laser ablation deposi-

tion. Consequently, these materials are regarded as

possible alternatives for the more conventional RT

epitaxially grown thin films. Combination of CMR

and magnetostriction may be useful in applications.

In general, the phase diagrams are complex, showing

different combinations of insulator (or semiconduc-

tor)–metal transitions, antiferromagnetic to para-

magnetic or ferromagnetic transitions, charge order

(influenced by doping), etc. (Duc and Brommer 2002,

p. 174 ff). These perovskites are included here, be-

cause, in some cases, the structure is described as a

nanocrystalline heterogeneous composite of ferro-

magnetic clusters in an antiferromagnetic (semicon-

ducting) matrix (or the other way round).

3. Concluding Remarks

For applications, both zero-magnetostriction (soft-

magnetic) materials and materials exhibiting giant

magnetostrictive effects (for actuators) are of interest.

Reliable magnetostrictive devices (MEMS) have been

designed on the basis of Terfenol and Terfenol-D

(TbDyFe

2

). When using amorphous thin films, it is

preferable to replace (some) iron by cobalt, because of

the asperomagnetic nature of the Fe-subsystem. Mag-

netoelastic effects in thin films and multilayers are of

fundamental interest too, in particular because a bet-

ter understanding of the magnetoelastic coupling can

be obtained by studying surface (interface) effects.

Microactuators and motors have been designed,

taking advantage of wireless magnetic excitation,

in first instance at room temperature (or higher

temperatures). For cryogenic applications, magneto-

strictive actuators require low-temperature magne-

tostrictive materials. In practice, Tb

0.6

Dy

0.4

Zn

1

(Terzinol) single crystals have been used (Teter—see

Duc and Brommer 2002, p. 191), but also perovskites

778

Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Heterogeneous Materials

and rare-earth superlattices must be considered as

possible candidates for such applications. Giant mag-

netostriction has been observed also in high T

C

su-

perconductors, e.g., in Bi

2

Sr

2

CaCu

2

O

8

single crystals

and YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

ceramics (reviewed by Szymczak

1999).

See also: Magnetic Films: Anisotropy; Magnetic

Layers: Anisotropy; Magnetic Microwires: Manufac-

ture, Properties and Applications; Magnetoelastic

Phenomena; Magneto-impedance Effects in Metallic

Multilayers; Monolayer Films: Magnetism; Multilay-

ers: Interlayer Coupling;

Bibliography

Du Tre

´

molet de Lacheisserie E 1993 Magnetostriction: Theory

and Applications of Magneto-elasticity. CRC Press, Boca

Raton

Du Tre

´

molet de Lacheisserie E 1999 Magnetism. Presses

Universitaires de Grenoble

Duc N H, Brommer P E 2002 Magnetoelasticity in nanoscale

heterogeneous magnetic materials. In: Buschow K H J (ed.)

Handbook of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier Science, North-

Holland, Amsterdam, Vol. 14, p. 89

Duc N H, Danh T M, Thanh H N, Teillet J, Lie

´

nard A 2000

Structural, magnetic, Mo

¨

ssbauer and magnetostrictive stud-

ies of amorphous Tb(Fe

0.55

Co

0.45

)

1.5

films. J. Phys.: Condens.

Matter 12, 7957

Hai N H, Dempsey N M, Givord D 2003 Hard magnetic Fe–Pt

alloys prepared by cold-deformation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.

262 (3), 353

Sander D 1999 The correlation between mechanical stress and

magnetic anisotropy in ultrathin films. Rep. Progr. Phys. 62,

809

Szymczak H 1999 From almost zero magnetostriction to giant

magnetostrictive effects: recent results. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 200, 425

P. E. Brommer and N. H. Duc

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Magneto-impedance Effects in Metallic

Multilayers

Magnetic sensor technology is a strongly growing in-

dustry which has been satisfied in some areas by

magnetoresistors, giant magnetoresistors (GMRs; see

Giant Magnetoresistance), fluxgates and other tech-

nologies. Giant magneto-impedance (GMI) is a can-

didate to equal or even overtake some of these

emergent sensor systems in terms of performance and

lower cost (Mohri et al. 1995). The magneto-imped-

ance phenomenon implying a change of the complex

resistivity of a ferromagnetic conductor caused by an

external magnetic field has been known for more than

50 years. However, a giant change of the impedance

of more than 100%, which certain soft magnetic

materials exhibit in the presence of a weak external

magnetic field (less than 1–10 Oe), has been found

quite recently. It was reported (Panina et al. 1994)

that in CoFeSiB near-zero magnetostrictive amor-

phous wires and ribbons having a well-defined

circumferential (or transverse) anisotropy, the im-

pedance sensitivity to the direct current (d.c.) longi-

tudinal external field is B25–100%/Oe at a frequency

of 1–10 MHz. It was also understood that although

GMI can be considered as a high-frequency analog to

GMR, it has quite a different mechanism. If GMR

has a quantum origin, occurring due to a spin-de-

pendent scattering of conductive electrons, GMI is a

classical phenomenon that occurs due to a re-distri-

bution of the alternating current (a.c.) density in a

magnetic conductor subjected to an external mag-

netic field. Since then, the research on GMI has

expanded rapidly, involving new materials such as

magnetic/metallic multilayers, new concepts such as

asymmetrical GMI, and excitation at higher frequen-

cies (up to 10 GHz).

Recent progress in GMI technology is related to

utilising magnetic/metallic multilayers. Using thin

film materials is more preferable in a number of ap-

plications, because of compatibility with integrated

circuit technology, avoiding soldering problems, and

allowing miniaturization. Along with this, the prin-

cipal advantage of magnetic/metallic multilayers is

that the nominal values of the impedance change can

be several times larger, reaching 400–600%. It has

been reported (Morikawa et al. 1997) that in CoSiB/

Cu/CoSiB multilayers of 7 mm thick, the impedance

change is as large as 340% at a frequency of 10 MHz

and a d.c. magnetic field of 9 Oe.

A simple three-layer sandwich film F/M/F consist-

ing of two outer ferromagnetic layers (F) and an in-

ner lead (M), having much higher conductivity

ensures large impedance changes under the applica-

tion of a d.c. magnetic field. As layers F, Co-based

amorphous films or NiFe films are typically used

since they have a small magnetostriction and good

soft magnetic properties. Using noble metals (Cu, Ag,

Au) for the inner lead M gives the necessary conduc-

tivity ratio (between layers M and F) in the range of

10–50. Since the inner conductivity is much higher,

the resistance R of the total structure is determined

by that for the layer M and the a.c. current mainly

flows along it, whereas the magnetic layers contribute

to the inductive part of the impedance. The latter can

be considerably larger than R at relatively low fre-

quencies because of a high value of the a.c. perme-

ability which, for certain magnetic configurations, is

also sensitive to the d.c. magnetic field.

The problem of calculating the impedance Z in a

three-layer film F/M/F can be solved exactly account-

ing for the skin effect, the a.c. permeability tensor

779

Magneto-impedance Effects in Metallic Multilayers