Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

value of c

k

using Eqns. (4)–(6) and compare this with

the absolute maximum possible value, c

kmax

. This

can be calculated using the same equations combined

with the maximum possible value of the G function,

G

max

, which is obtained for a perfect mirror and is

given by (Gamble et al. 1985)

G

max

¼ð1 G

2

Þ

1=2

ð7Þ

Because of the insensitivity of the gain function to the

mirror reflectance over a range of r

m

values, it is

quite common for the potential Kerr coefficient to be

within a few percent of the maximum that would be

possible if the design were perfect. This is shown in

Table 2 for the three designs marked ( þ) in Fig. 4 for

R ¼0.1, 0.2, and 0.3.

It may be noted that the extra complexity that

would be needed to achieve the perfect enhancement

does not usually warrant the additional effort since

errors during fabrication of such multilayer systems

are likely to lead to imperfections in performance.

5. Enhancement Process

It is useful to obtain a physical understanding of why

enhancement of the magneto-optical Kerr effect oc-

curs in the multilayer systems described above. There

are two simple reasons for this. First, the overall re-

flectance is reduced and this clearly leads to an in-

crease in Kerr rotation even if the Kerr coefficient

remains unchanged. More importantly, however, for

any chosen value of system reflectance, the Kerr co-

efficient has been increased to the maximum possible

value that the intrinsic properties of the magnetic

material will allow. This is accomplished through

multiple interactions of the radiation with a thin film

of the material. This is achieved using a high-reflect-

ance mirror in such a way that all radiation not re-

flected from the system is absorbed by the magnetic

layer. This maximizes the magneto-optic interaction

of the incident radiation with the system.

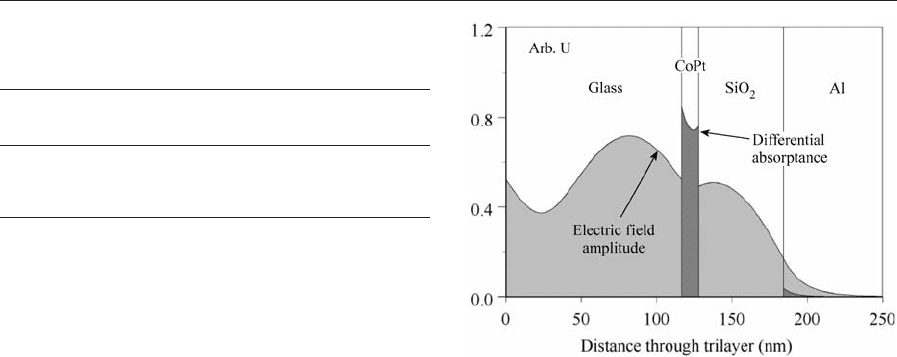

These points are illustrated in Fig. 5, which shows

the electric field amplitude and differential ab-

sorptance throughout a simple trilayer structure.

The design actually corresponds to that indicated in

Fig. 4 for R ¼0.1 at a wavelength of 350 nm. It

should be noted that the curve represents the ampli-

tude of the electric wave through the various layers

and should not be thought of as a traveling wave. In

the incident medium (glass) therefore, we see a stand-

ing wave with nonzero nodes resulting from combi-

nation of the incident wave and the reflected wave

that corresponds to the 10% reflected energy. The

fields gradually decrease through the spacer and be-

come very low within the highly reflecting aluminum

mirror.

Differential absorptance indicates the variation of

optical absorption throughout the system and the

total dark area in Fig. 5 corresponds to the total ab-

sorption by the trilayer. Most important is the fact

that virtually all of the radiation not reflected by the

system is absorbed in the magnetic layer. Very little is

lost to the mirror, either by absorption or in trans-

mission. It is this fact that results in maximization of

the potential Kerr coefficient since all radiation not

reflected from the system is available to stimulate the

magneto-optical effect.

6. Longitudinal and Transverse Effects

The general principles of enhancement, outlined

above for the normal incidence polar Kerr effect,

also apply to the longitudinal and transverse effects.

In such cases one is working at oblique incidence and

account must be taken of the orientation of the po-

larization state of the incident radiation with respect

to the plane of incidence. The longitudinal case has

been considered in some detail by Keay and Lis-

sberger (1968). In the transverse case, the effect is

usually described in terms of the ratio of the mag-

netization-sensitive reflectance change, DR, to the

Figure 5

Electric field amplitude and differential absorptance as

a function of distance through a trilayer designed for

R ¼ 0.1.

Table 2

Trilayer designs corresponding to the three points

marked ( þ) in Fig. 4.

R (%)

d

M

(nm)

d

s

(nm) 7k7 10

2

y

k

(1)

c

k

/c

kmax

(%)

0.1 11.4 56.3 0.9 1.69 96.9

0.2 14.1 48.9 0.8 1.01 97.2

0.3 18.1 42.5 0.7 0.72 96.5

810

Magneto-optical Effects, Enhancement of

usual isotropic intensity reflectance, R, for P-polar-

ized radiation. It is clear that enhancement can be

obtained through the control of the reflectivity of the

P-polarized state and maximization of the interaction

of the radiation with the magnetic layer. The details

for these cases will, to some extent, depend on the

exact experimental arrangement being used to detect

the effects.

7. Summary

An outline has been given of the means by which the

normal incidence polar Kerr effect can be enhanced to

improve the sensitivity with which it may be detected.

The method relies on the use of three- or four-layer

systems that control the reflectivity of the coating

surface while, at the same time, maximizing the

magneto-optical interaction of the radiation with the

magnetic medium.

See also: Magneto-optic Recording: Overwrite and

Associated Problems; Magneto-optic Recording:

Total Film Stack, Layer Configuration; Optical and

Magneto-optic Data Storage: Channels and Coding

Bibliography

Atkinson R 1993 Design of magneto-optic phase-optimized

trilayer systems for the enhancement of the polar Kerr-effect.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 124, 178–84

Atkinson R, Salter I W, Xu J 1991 Quadrilayer magneto-optic

enhancement with zero Kerr ellipticity. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 102, 357–64

Egashira K, Yamada T 1974 Kerr-effect enhancement and im-

provement of readout characteristics in MnBi film memory.

J. Appl. Phys. 45, 3643–8

Faraday M 1845 Experimental researches in electricity. Proc.

R. Soc. 5, 567–9

Gamble R, Lissberger P H, Parker M R 1985 A simple analysis

for the optimization of the normal polar magneto-optical

Kerr effect in multilayer coatings containing a magnetic film.

IEEE Trans. Magn. 21, 1651–3

Keay D, Lissberger P H 1968 Longitudinal Kerr magneto-optic

effect in multilayer structures of dielectric and magnetic films.

Opt. Acta 15, 373–88

Kerr J 1877 On rotation of the plane of polarisation by reflec-

tion from a magnetic pole. Philos. Mag. 3, 321–43

R. Atkinson

The Queen’s University, Belfast, UK

Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband

Transitions, Microscopic Models of

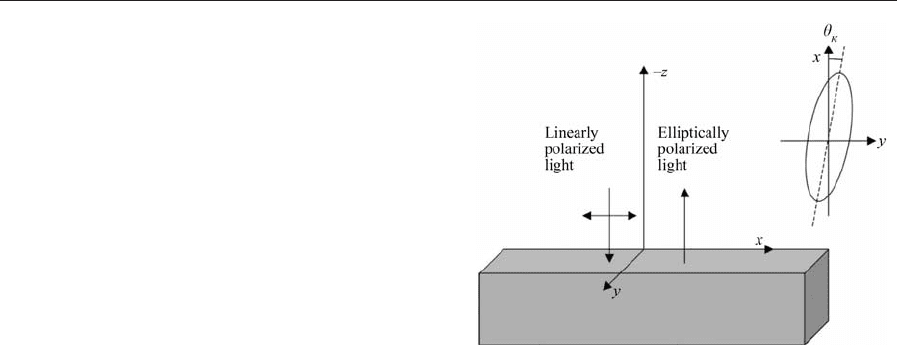

Magneto-optical methods are widely used to study

the magnetic properties of materials. These experi-

ments consider the response of a magnetic medium to

the incident plane polarized light. When linearly

polarized light is reflected or refracted it generally

becomes elliptically polarized, as shown in Fig. 1. The

main axis of the ellipse is rotated through angle

y

k

with respect to the polarization direction of the

incident light. The magneto-optical Kerr effect

(MOKE) considers the reflected light, while the

Faraday effect deals with the refracted light. y

k

is

called the Kerr/Faraday rotation angle. The other

important parameter is the ellipticity (Z

k

) of the out-

going light.

The discussion below deals primarily with the Kerr

effect that can be easily extended to the Faraday

effect. To make the analysis of this complex problem

somewhat simpler we assume normal incidence of

light and assume the z-axis to be normal to the sur-

face of the sample. The light traveling through vac-

uum or air with refractive index n ¼1 is reflected

from a sample with refractive index n. Let us consider

the electric vector of the linearly polarized light.

E

inc

¼ E

0

#

e

x

e

ikziot

ð1Þ

where e

ˆ

x

is the polarization vector along the x-axis, k

is the wave vector, o is the frequency of the wave, and

E

0

is the amplitude. This expression can be rewritten

in terms of right and left circularly polarized light as

follows:

E

inc

¼ E

r

þ E

l

ð2Þ

where

E

r=l

¼ E

0

ð

#

e

x

7i

#

e

y

Þe

ikziot

ð3Þ

This wave has equal right and left components.

Using the boundary conditions, the following

relation is obtained for the incident, E

inc

, and the

Figure 1

Schematic configuration of polar Kerr effect geometry.

811

Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband Transitions, Micro scopic Models of

reflected, E

refl

, electric vectors:

E

refl

¼

1 n

1 þ n

E

inc

ð4Þ

Replacing E

inc

with its right-(n

r

) and left-(n

l

) circu-

larly polarized components one gets

E

refl

¼

1 n

r

1 þ n

r

E

inc;r

þ

1 n

l

1 þ n

l

E

inc;l

¼

E

0

2

1 n

r

1 þ n

r

ð

#

e

x

þ i

#

e

y

Þþ

1 n

l

1 þ n

l

ð

#

e

x

i

#

e

y

Þ

e

ikziot

ð5Þ

which is elliptically polarized light if n

r

an

l

. The Kerr

rotation angle and ellipticity are given by

y

k

¼

ReðE

refl

#

e

y

Þ

ReðE

refl

#

e

x

Þ

¼ Im

n

r

n

l

1 n

r

n

l

;

Z

k

¼

ImðE

refl

#

e

y

Þ

ReðE

refl

#

e

x

Þ

¼ Re

n

r

n

l

1 n

r

n

l

ð6Þ

The positive sign of the Kerr angle is considered for

the rotation from the x-axis to the y-axis. Keep in

mind that the direction of propagation for the

reflected beam is z.

The corresponding parameters for the Faraday

effect are

y

F

¼

1

2c

ozReðn

r

n

l

Þ;

Z

F

¼tanh

1

2c

ozImðn

r

n

l

Þ

ð7Þ

where c is the speed of light and z is the distance

from the interface. These expressions are valid for

7n

r

n

l

7{n

r

. We see from these equations that re-

flected and refracted waves are elliptically polarized

due to the difference in the refractive indices of the

medium for the left and right polarized light. The

index of refraction is related to the dielectric constant

e and conductivity tensor s as follows:

n

2

¼ e ¼ 1 þ i

4p

o

s ð8Þ

The left-handed () and the right-handed (þ) com-

ponents of the conductivity are given by

s

7

ðoÞ¼s

xx

ðoÞ7is

xy

ðoÞð9Þ

and the conductivity tensor for a medium with three-

fold or higher rotational symmetry about the z-axis

has the following form:

s ¼

s

xx

s

xy

0

s

xy

s

xx

0

00s

xx

0

B

@

1

C

A

ð10Þ

Combining Eqns. (6), (8)–(10), the Kerr rotation

parameters are given by

y

k

¼ Re

4ps

xy

onð1 n

2

Þ

; Z

k

¼ Im

4ps

xy

onð1 n

2

Þ

ð11Þ

We see from Eqn. (11) that a system gives rise

to the Kerr effect if the off-diagonal component of

its conductivity tensor, s

xy

, is not zero. Now, the

Onsager reciprocal relation s

ij

(M) ¼s

ji

(M) along

with Eqn. (10) gives s

xy

(M) ¼s

xy

(M) and

s

ii

(M) ¼s

ii

(M), where M is the magnetization vec-

tor along the z -axis. Thus there is no Kerr rotation in

a paramagnet or antiferromagnet because s

xy

(M) ¼

s

xy

(M) leads to an equal and opposite contribu-

tion for the identical spin-up and spin-down densities

of states. Also, s

ii

and s

xy

have odd-power and even-

power dependence respectively on M. As a result, the

rotation parameters are linear functions of M when

the higher order terms are neglected. The Kerr rota-

tion for the geometry considered here is known as

polar Kerr rotation.

The conductivity tensor is determined by intraband

and interband electronic transitions in response to

the applied electromagnetic radiation. Thus the com-

putation of the conductivity tensor requires the

electronic states of the system. The electronic states

are determined by the self-consistent solutions of the

one-electron Schro

¨

dinger equations

ðD þ V

eff

Þc

k

-

l

¼ E

k

-

c

k

-

l

ð12Þ

where V

eff

is the effective potential including spin–

orbit interactions,

~

k is the wavevector and l is the

band index.

The Drude model is used to calculate the intraband

contribution to the diagonal component of the con-

ductivity tensor. The conductivity in this model is

given by (Ziman 1972)

s

intra

ðoÞ¼

s

0

1 iot

ð13Þ

where the d.c. conductivity s

0

is related to the plasma

frequency o

p

and the relaxation time t of the band

states by

4ps

0

¼ o

2

p

t ð14Þ

The calculated band structure is used to compute

o

p

using the following expression (Mazin et al. 1989):

o

2

p

¼

4pe

2

O

X

k

-

l

7V

k

-

l

7

2

dðE

k

-

l

E

F

Þð15Þ

where O is the volume of the primitive cell of the

system and

V

k

-

l

¼ / k

-

l7r7 k

-

lS ð16Þ

812

Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband Transitions, Microscopic Models of

is the mean velocity of an electron in state 7klS and

E

F

is the Fermi energy.

s

0

and o

p

are used to calculate t and then s

intra

(o).

The interband contribution to the conductivity

tensor is related to matrix elements of the interaction

potential between the electrons and the electromag-

netic field given by:

H

0

¼

e

mc

p

-

A

-

ð17Þ

where A is vector potential and

p

-

¼ p

-

þ

_

4mc

2

s rVðrÞð18Þ

with s as the Pauli spin matrices and

~

p as the electron

momentum. The second term in ~p leads to the spin–

flip transitions. It has been found to be negligible

compared to the first term and is usually ignored.

Treating H

0

as a perturbation in the random phase

approximation, without allowance for the local field

effects, the imaginary part of the off-diagonal con-

ductivity tensor is

s

2xy

¼

pe

2

4m

2

_oO

X

k

-

ll

0

f7/ k

-

l

0

7p

7 k

-

lS7

2

7/ k

-

l

0

7p

þ

7 k

-

lS7

2

gdð_o E

ll

0

Þð19Þ

where p

þ

and p

are electron momentum operators

corresponding to right- and left-circularly polarized

light and 7

~

klS and 7

~

kl

0

Sare occupied and unoccu-

pied states, respectively (see for example Bennet and

Stern 1965, Wang and Callaway 1974). The real part

of the diagonal component of the conductivity ten-

sor, s

1xx

, is given by a similar expression where p

þ

and p

contributions are added. The Kramers–

Kronig dispersion relations are used to find the other

parts of these components.

The selection rules for the dipole matrix elements

in terms of the orbital quantum numbers (l, m

l

) are

Dl ¼71 and Dm

l

¼1 for p

þ

and Dm

l

¼1 for p

.In

the absence of spin–orbit interactions, p

þ

and p

contributions in Eqn. (19) cancel each other exactly

(s

xy

¼0) due to the degeneracy of the states with

magnetic orbital quantum numbers m

l

and m

l

.Asa

result there is no Kerr rotation in such a system.

Spin–orbit interactions lift the above mentioned de-

generacy of the electronic states so that p

þ

and p

contributions no longer cancel each other, giving a

finite value for s

xy

. Thus a system must have spin

moment (asymmetric spin-up and spin-down densi-

ties of states) with spin–orbit interactions to produce

Kerr rotation.

The off-diagonal components of the conductivity

tensor (Eqn. (19)) and hence the Kerr rotation (Eqn.

(11)) is determined by the dipole matrix elements be-

tween the occupied and unoccupied electronic states

of the same spin separated by the incident photon

energy _o. Since the Kerr parameters are propor-

tional to the off-diagonal component of the conduc-

tivity tensor, one can qualitatively try to relate the

features in the magneto-optic spectra by assuming the

matrix elements in Eqn. (19) to be the same for all

transitions. In this case s

xy

is proportional to the

joint density of states (JDOS) as follows:

s

xy

ðoÞp

1

o

Z

o

F

o

F

o

n

m

ðo

0

Þn

m

ðo þ o

0

Þdo

0

þ

Z

o

F

o

F

o

n

k

ðo

0

Þn

k

ðo þ o

0

Þdo

0

ð20Þ

where n

m,k

(o

0

) and n

m,k

(o þo

0

) are the spin-up(m)

and spin-down (k) densities of states (DOS) for the

occupied and unoccupied states respectively and o

F

refers to the Fermi energy. It must be kept in mind

that constant matrix element approximation is inad-

equate for a quantitative comparison of this rather

weak effect.

The magneto-optical materials have been actively

studied for several decades in terms of their applica-

tions as rewritable data storage devices. The large

Kerr rotation allows the increase of signal to noise

ratio and as a result the density of recording. Cur-

rently, materials with Kerr rotation of about 0.31 are

used for magneto-optical recording. Research is now

concentrated on materials with a Kerr rotation above

0.31. Also, the Curie temperature (T

c

) should be such

that one can easily go above it to write and stay

below it to read. Thus, along with the exchange pa-

rameters for appropriate T

c

, a practical magneto-

optical system must have large magnetization and

spin–orbit interactions to produce a large enough

Kerr rotation. One of the common ways to achieve

this combination is by creating a mixture of 3d ele-

ments with large magnetization and heavy elements

with large spin–orbit coupling. The materials cur-

rently in use are based on amorphous (Tb, Gd)

x

(Fe, Co)

1x

(x ¼0.2–0.3) with Kerr rotation of about

0.2–0.31 around 633 nm wavelength of light (Bloomb-

erg et al. 1996).

Finally, as an example of intraband and interband

contributions to the Kerr parameters we consider

MnBi, an interesting system with one of the largest

Kerr rotations known. MnBi has a hexagonal struc-

ture with four atoms per unit cell. We have studied

the Kerr effect in MnBi using the first-principle rel-

ativistic self-consistent band structure calculations.

The large magnetization in this system comes from

Mn(3.6 m

B

) and Bi is responsible for the appreciable

spin–orbit coupling (Sabiryanov and Jaswal 1996).

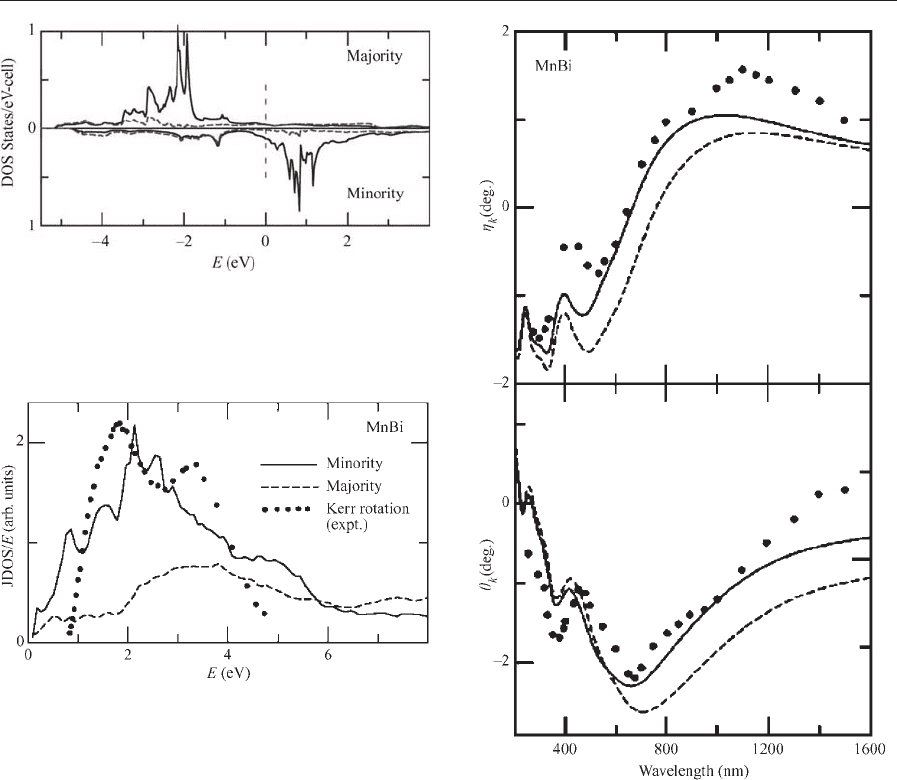

Figure 2 shows the spin-polarized DOS for MnBi.

The major peaks in the DOS are due to the Mn

d-states. The interband contribution to the Kerr

rotation in MnBi comes primarily from p and d

states (Dl ¼71). The Kerr-active region of the

813

Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband Transitions, Micro scopic Models of

electromagnetic spectrum for MnBi can be qualita-

tively seen from the JDOS (Eqn. (20)) for spin-up and

spin-down states plotted in Fig. 3. Figure 3 also

shows the experimental data for Kerr rotation for

MnBi (Di et al. 1992). One can see from Fig. 3 that

JDOS do a good job of predicting that the Kerr-

active region of MnBi is centered around 2–3 eV. The

minority spin JDOS has a large peak around 2 eV

that arises from a modest peak around 1.4 eV below

Fermi energy and a large peak at 0.6 eV above E

F

in

the DOS of MnBi in Fig. 2. The transitions are be-

tween hybrid bands formed by Bi p- and Mn d-states.

The majority-spin JDOS has a small broad peak

around 3.3 eV. The transitions from hybrid Bi p- and

Mn d-bands to more dispersed Mn and Bi sp-bands

are responsible for the smaller second peak in the

Kerr rotation angle around 3.3 eV.

For a quantitative comparison, the calculated Kerr

rotation and ellipticity are compared with the exper-

imental data in Fig. 4. First, overall there is good

agreement between theory and experiment. The largest

Kerr rotation of 2.31 is around 2 eV (630 nm). Figure 4

also shows the calculated Kerr rotation without an

intraband contribution. We see that the intraband

contribution is appreciable at longer wavelengths but

becomes negligible below 600 nm.

In spite of the large Kerr rotation MnBi has not

become a data storage device so far. This is because

MnBi undergoes structural phase transition from a

low-temperature hexagonal ferromagnetic phase to

the high-temperature orthorombic paramagnetic

phase near its Curie temperature. This makes it

Figure 4

Kerr rotation (y

k

) and ellipticity (Z

k

) for MnBi. Dots

represent the experimental data at 85 K from Di et al.

(1992). The full line gives the results with interband and

intraband contributions while the dashed line

corresponds to the interband contribution only.

Figure 3

Spin-resolved JDOS of MnBi and the Kerr rotation data

from Di et al. (1992).

Figure 2

Spin-polarized total and projected DOS of MnBi. The

zero on the energy axis corresponds to the Fermi energy.

814

Magneto-optics: Inter- and Intraband Transitions, Microscopic Models of

unsuitable for recording applications. Scientists con-

tinue to make efforts to overcome this problem and

enable the large Kerr rotation in MnBi to be exploi-

ted for data storage applications (Bandaru et al. 1998,

Sabiryanov and Jaswal 1999).

See also: Density Functional Theory: Magnetism;

Magneto-optic Recording: Total Film Stack, Layer

Configuration; Magneto-optic Recording: Overwrite

and Associated Problems; Magneto-optical Effects,

Enhancement of

Bibliography

Bandaru P, Sands T D, Kubota Y, Marinero E E 1998 De-

coupling the structural and magnetic phase transitions in

magneto-optic MnBi thin films by the partial substitution of

Cr for Mn. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 2337–9

Bennett H S, Stern E A 1965 Faraday effect in solids. Phys.

Rev. 137, 448–61

Bloomberg D S, Naville Connell G A, Mansuripur M 1996

Magnetooptical recording. In: Mee C D, Daniel E D (eds.)

Magnetic Recording Technology. McGraw-Hill, Boston,

Chap. 10, pp. 10.1–10.101

Di G Q, Iwata S, Tsunashima S, Uchiyama S 1992 Magneto-

optical Kerr effect of MnBi and MnBiAl films. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 104–7, 1023–4

Mazin I I, Maksimov Ye G, Rashkeev S N, Uspenskii Yu A

1989 Microscopic calculations of the dielectric response func-

tion of metals. In: Golovashkin A I (ed.) Metal Optics and

Superconductivity. Nova Science, New York, pp. 1–106

Sabiryanov R F, Jaswal S S 1996 Magneto-optical properties of

MnBi and MnBiAl. Phys. Rev. B. 53, 313–7

Sabiryanov R F, Jaswal S S 1999 Magneto-optical properties of

MnBi doped with Cr. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 5109–11

Wang C S, Callaway J 1974 Band structure of nickel: Spin–

orbit coupling, the Fermi surface, and the optical conductiv-

ity. Phys. Rev. B 9, 4897–907

Ziman J M 1972 Principles of the Theory of Solids. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK

R. F. Sabiryanov and S. S. Jaswal

University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Magnetoresistance in Transition Metal

Oxides

If the electrical resistance of a material depends on

the strength of the magnetic field which it experi-

ences, then the material is said to show the property

of magnetoresistance (MR). This property has many

useful applications: it enables magnetic field strength

to be deduced from a relatively simple measurement

of electrical resistance, and it allows magnetic fields

to control the flow of current in a circuit, i.e., a mag-

netic switch. As recently as 1988, a 50% drop in the

resistance of an Fe/Cr multilayer device in a field of

2 T at a temperature of 4.2 K was described as ‘‘huge’’

(Baibich et al. 1988). Since that time, considerable

progress has been made towards producing a mate-

rial that shows a larger effect at higher temperatures

in weaker fields, with most of the recent research

focusing on mixed-metal oxides containing manga-

nese, for example La

1–x

Sr

x

MnO

3

. The level of success

has been such that the word used to describe the

magnetoresistance has changed from huge, via giant

(GMR), to colossal (CMR), although at the time of

writing (2000) the cause of the enhancement is not

fully understood. The oxides that have shown the

most interesting behavior are described below; a

number of more detailed reviews are available (Battle

and Rosseinsky 1999, Bishop and Ro

¨

der 1997,

Ramirez 1997, Rao and Cheetham 1997).

1. Perovskites

The seminal paper in the study of MR in mixed-metal

oxides was concerned with Nd

0.5

Pb

0.5

MnO

3

(Kusters

et al. 1989), a compound that adopts the relatively

common, cubic (or pseudo-cubic) perovskite crystal

structure. This structure has the general formula

ABO

3

, with the possibility of substitution on the A

site (ideally 12-coordinated by oxide ions) to form

A

1–x

A

0

x

BO

3

, or on the B site (6-coordinated) to form

AB

1–x

B

0

x

O

3

. Many aspects of the behaviour of A-site

substituted Nd

0.5

Pb

0.5

MnO

3

, including the adoption

of a perovskite-related structure, have subsequently

been shown to be common among MR oxides. The

majority of the compounds to be discussed below

contain manganese in a mixed valence state, that is,

the average oxidation state of the transition-metal

cation lies between þ3 and þ4, and the average

number of electrons in the 3d electron shell of each

cation is therefore non-integral, lying between 4 and 3

for Mn

3 þ

and Mn

4 þ

respectively. At temperatures

above 200 K, the valence electrons are localized

and the electrical conductivity of Nd

0.5

Pb

0.5

MnO

3

is

activated.

However, a transition from an insulating to a me-

tallic state occurs on cooling through 185 K. This is

typical of MR oxides, as is the fact that the Curie

temperature (T

C

), below which the material is

ferromagnetic, coincides with the temperature of the

metal–insulator (MI) transition. The coexistence of

metallic conductivity and ferromagnetism is often

accounted for in terms of the double-exchange mech-

anism (Zener 1951), which argues that the ease of

transferring the extra electron associated with a

Mn

3 þ

cation to a neighboring Mn

4 þ

cation, thus

establishing a current, is greatest when the outer

electrons on the two cations have parallel spins, and

that ferromagnetic coupling of the atomic magnetic

moments therefore reduces the electrical resistivity.

The MR effect is greatest at temperatures slightly

above T

C

, where the application of a magnetic field

815

Magnetoresistance in Transition Metal Oxides

increases the degree of spin alignment in a material

which is susceptible to short-range magnetic cou-

pling, thus reducing the spin-scattering of the con-

duction electrons and effectively moving the MI

transition to higher temperatures.

Hence, the resistivity of Nd

0.5

Pb

0.5

MnO

3

decreases

by two orders of magnitude when it is subjected to a

field of 11 T at 190 K, with T

C

¼18471 K. This re-

duction, although large enough to be useful, is oc-

curring at too low a temperature and too high a field

to be of practical benefit. In the late 1990s, a great

deal of effort was expended in order to shift the re-

gion of maximum effect to higher temperatures and

to reduce the value of the required field. The perovs-

kites having the general formula Ln

1–x

A

x

MnO

3

,

where Ln is a metal from the lanthanide series and

A is an alkaline earth (group II) metal, were studied

in great detail. Changes in the value of x produced

changes in the mean oxidation state of the manganese

cations, and hence changes in the population of the

conduction (3d) band. They also caused a variation in

the mean size of the cations, and hence subtle changes

in the details of the crystal structure.

This chemical approach resulted (Urushibara et al.

1995) in the observation of 90% MR (defined as

100[r(B)–r(0)]/r(0)) at 300 K in La

0.875

Sr

0.175

MnO

3

, albeit in a field of 15 T. Thus, the tempera-

ture problem was solved, but not that of the field

strength. It should be noted that the oft-cited chem-

ical similarity of the lanthanide elements cannot be

assumed in this research area. The electronic phase

diagrams of Ln

1–x

A

x

MnO

3

are very sensitive to the

particular cations (Ln and A) involved, as well as to

their concentration. Although perovskites containing

manganese have dominated recent research into MR

effects in oxide materials, a number of manganese-

free systems have also been studied. One such system

(Kobayashi et al. 1998) is Sr

2

FeMoO

6

, a perovskite

with an ordered arrangement of two cations over the

6-coordinate sites. This compound is metallic with

T

C

B415 K, and it shows 10% MR in 7 T at 300 K.

Note that in analyzing magnetotransport data on

these materials there is a need to distinguish between

intrinsic MR and spin-dependent intergrain tunnel-

ling effects (Hwang et al. 1996), the latter being im-

portant in low fields.

2. n ¼2 Ruddlesden–Popper Phases

The perovskite phases described above are the n ¼N

members of the Ruddlesden–Popper family having

the general formula (A, A

0

)

n þ1

(B, B

0

)

n

O

3n þ1

. CMR

has also been observed in compounds which corre-

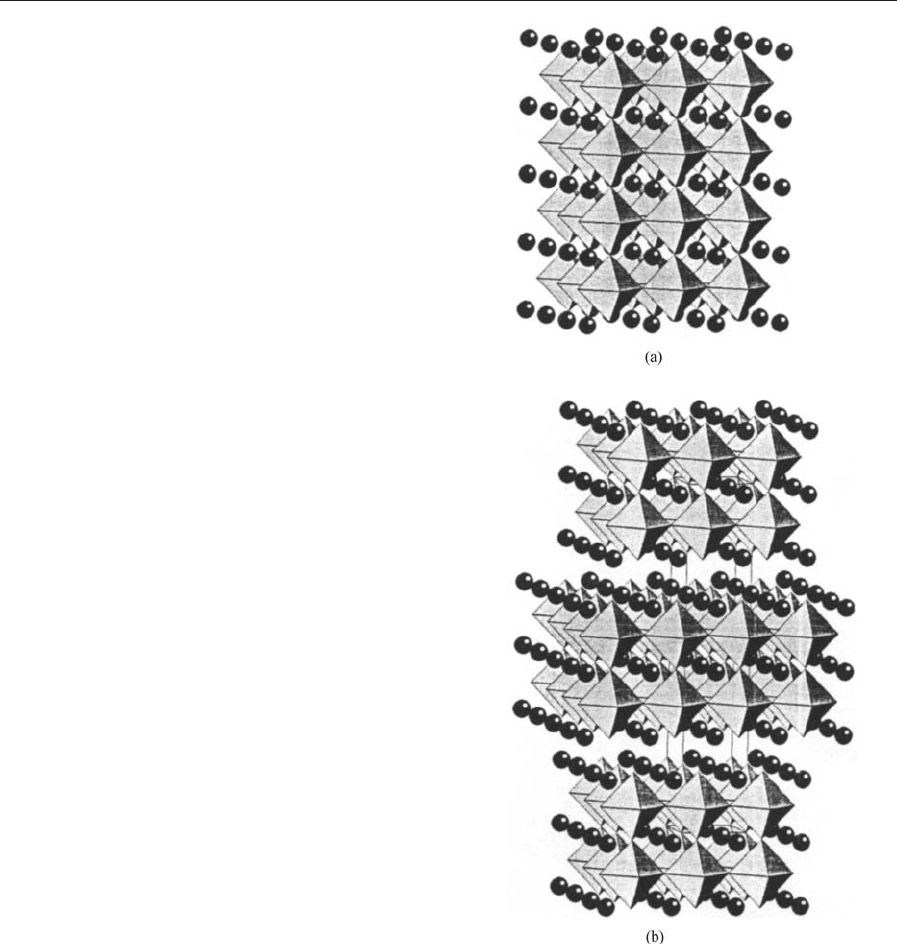

spond to the n ¼2 member of the series (Fig. 1). In

the case of n ¼N, a three-dimensional, infinite net-

work of vertex-sharing BO

6

octahedra is present,

with the A cations occupying interstices between

the octahedra. For n ¼2, the octahedral network is

infinite in two dimensions, but it is broken into

blocks, each only two (i.e., n ) octahedra wide, along

the third direction. The two-dimensional nature of

this structure introduces anisotropy into the electron-

ic properties of the oxides. Sr

1.8

La

1.2

Mn

2

O

7

was one

of the first n ¼2 compositions to be studied from the

Figure 1

Crystal structures of the Ruddlesden–Popper phases

having (a) n ¼N (perovskite) and (b) n ¼2. MnO

6

octahedra are shown, along with A site cations.

816

Magnetoresistance in Transition Metal Oxides

point of view of CMR (Moritomo et al. 1996). It was

found to show a MI transition coincident with the

Curie temperature, T

C

¼126 K, although the con-

ductivity parallel to the infinite perovskite blocks was

two orders of magnitude greater than that in the

perpendicular direction.

MR was observed both parallel and perpendicular

to the blocks, and the low-field effect was much

stronger than had been observed in n ¼N (La,

Sr)MnO

3

; in the two-dimensional material r(0)/

r(H) ¼110% in 0.3 T and B3000% in 1 T. The

chemical sensitivity of these systems is demonstrated

by the behavior of Sr

1.6

La

1.4

Mn

2

O

7

, which, in con-

trast to that of Sr

1.8

La

1.2

Mn

2

O

7

, is markedly diffe-

rent parallel and perpendicular to the layers (Kimura

et al. 1996), with the strongest magnetoresistance

being in the latter direction. This has lead to com-

parisons being drawn between the multilayer devices

described above and these Ruddlesden–Popper

phases, which are now often referred to as ‘‘natural-

ly-layered manganites.’’ CMR has been reported in

n ¼2 compositions containing lanthanides other than

lanthanum (Battle and Rosseinsky 1999). As in the

case of the perovskites, the electronic properties are

very sensitive to the atomic number and concen-

tration of the lanthanide; CMR is not observed in

compounds containing the smaller lanthanides. It has

been shown that the microstructure of these com-

pounds can be very complex (Sloan et al. 1998), with

intergrowths of n ¼N perovskite breaking up the

regular n ¼2 structure.

3. Other Ruddlesd en–Popper Phases

There have been few reports of CMR in n ¼1

(K

2

NiF

4

-like) phases, in which Mn

3 þ

/Mn

4 þ

charge

ordering appears to be common. The most promising

system studied to date is perhaps Ca

2–x

Ln

x

MnO

4

(0oxo0.2, Ln ¼Pr, Sm, Gd, Ho), with 64% MR

being observed in Ca

1.92

Pr

0.08

MnO

4

in 7 T at 40 K

(Maignan et al. 1998). The n ¼3 phases studied to

date have shown lower MR ratios.

4. Pyrochlores

The observation of CMR in the pyrochlore

Tl

2

Mn

2

O

7

(Shimakawa et al. 1996) increased the

breadth of contemporary magnetotransport research.

Tl

2

Mn

2

O

7

orders ferromagnetically at 142 K, and the

MR is largest in this temperature region (86% in 7 T).

However, the pyrochlore is metallic both above and

below T

C

, that is, the onset of ferromagnetic ordering

is not accompanied by a MI transition. Furthermore,

there is apparently no mixed valency on the manga-

nese sublattice; only Mn

4 þ

is present. The CMR ob-

served in this compound is therefore not readily

explained by arguments based on double exchange,

and it has been shown (Ramirez and Subramanian

1997) that the MR can be increased by doping with

scandium to form Tl

2–x

Sc

x

Mn

2

O

7

.

During the last decade of the twentieth century

considerable progress was made in improving the

magnetotransport properties of mixed-metal oxides.

Perovskites that show a practically useful effect at

room temperature have been identified; unfortunately

the field needed to produce the effect is impractically

large. RP phases show an effect at lower fields, but at

temperatures too far below ambient to be useful. The

remaining challenge is to find new materials that

show a colossal effect at high temperatures. These

new materials may or may not be perovskite-related,

and they may or may not be manganese-based.

See also: Giant Magnetoresistance; Giant Magne-

toresistance: Metamagnetic Transitions in Metallic

Antiferromagnetics; Magnetoresistance: Anisotropic;

Magnetoresistance: Magnetic and Nonmagnet Inter-

metallics

Bibliography

Baibich M N, Broto J M, Fert A, Dau F N V, Petroff F,

Eitenne P, Creuzet G, Friederich A, Chazelas J 1988 Giant

magnetoresistance of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–5

Battle P D, Rosseinsky M J 1999 Synthesis, structure, and

magnetic properties of n ¼2 Ruddlesden-Popper mangan-

ates. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 4, 163–70

Bishop A R, Ro

¨

der H 1997 Theory of colossal magnetoresist-

ance. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2, 244–57

Hwang H Y, Cheong S W, Ong N P, Batlogg B 1996 Spin-

polarized intergrain tunneling in La

2/3

Sr

1/3

MnO

3

. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 77, 2041–4

Kimura T, Tomioka Y, Kuwahara H, Asamitsu A, Tamura M,

Tokura Y 1996 Interplane tunneling magnetoresistance in a

layered manganite crystal. Science 274, 1698–701

Kobayashi K L, Kimura T, Sawada H, Terakura K, Tokura Y

1998 Room temperature magnetoresistance in an oxide

material with an ordered double perovskite structure. Na-

ture 395, 677–80

Kusters R M, Singleton J, Keen D A, McGreevy R, Hayes W

1989 Magnetoresistance measurements on the magnetic semi-

conductor Nd

0.5

Pb

0.5

MnO

3

. Physica B 155, 362–5

Maignan A, Martin C, VanTendeloo G, Hervieu M, Raveau B

1998 Ferromagnetism and magnetoresistance in monolayered

manganites Ca

2–x

Ln

x

MnO

4

. J. Mater. Chem. 8, 2411–6

Moritomo Y, Asamitsu A, Kuwahara H, Tokura Y 1996 Giant

magnetoresistance of manganese oxides with a layered per-

ovskite structure. Nature 380, 141–4

Ramirez A P 1997 Colossal magnetoresistance. J. Phys.: Con-

dens. Matter 9, 8171–99

Ramirez A P, Subramanian M A 1997 Large enhancement of

magnetoresistance in Tl

2

Mn

2

O

7

—pyrochlore versus perovs-

kite. Science 277, 546–9

Rao C N R, Cheetham A K 1997 Giant magnetoresistance,

charge ordering, and related aspects of manganates and other

oxide systems. Adv. Mater. 9, 1009–20

Shimakawa Y, Kubo Y, Manako T 1996 Giant magnetoresist-

ance in Tl

2

Mn

2

O

7

with the pyrochlore structure. Nature 379,

53–5

817

Magnetoresistance in Transition Metal Oxides

Sloan J, Battle P D, Green M A, Rosseinsky M J, Vente J F

1998 A HRTEM study of the Ruddlesden–Popper compo-

sitions Sr

2

Ln

2

O

7

(Ln ¼Y, La, Nd, Eu, Ho). J. Solid State

Chem. 138, 135–40

Urushibara A, Moritomo Y, Arima T, Asamitsu A, Kido G,

Tokura Y 1995 Insulator–metal transition and giant magne-

toresistance in La

1–x

Sr

x

MnO

3

. Phys. Rev. B 51, 141103–9

Zener C 1951 Interaction between d-shells in the transition

metals. Phys. Rev. 82, 403–5

P. D. Battle

University of Oxford, UK

Magnetoresistance, Anisotropic

The electrical conductivity of spontaneously magnet-

ized materials depends on the relative orientation

of the electrical current and the magnetization. This

phenomenon, called anisotropic magnetoresistance

(AMR) or spontaneous magnetoresistance anisotropy

(SMA), was discovered by Lord Kelvin in the middle

of the nineteenth century. However, intensive investi-

gations on AMR started only in the 1950s with the

work of Smit (1951) and van Elst (1959). Although

technical applications of AMR were suggested in the

1970s, corresponding devices (sensors and read heads

for hard disks) (Go

¨

pel et al. 1989) were not introduced

commercially until about 20 years later.

The physical origin of AMR is the reduction of the

symmetry of a magnetized material compared to its

nonmagnetic state caused by the simultaneous pres-

ence of the magnetization and spin–orbit coupling.

The first qualitative models to describe AMR were

developed by Smit (1951) and Campbell et al. (1970)

and have been extended subsequently by others. A

parameter-free theoretical description of AMR has

been published (Banhart and Ebert 1995).

1. Phenomenological Description

For a material that is homogeneously magnetized

along the z-axis but otherwise isotropic, the conduc-

tivity tensor takes the following form (Kleiner 1966,

Cracknell 1973):

r ¼

s

>

s

H

0

s

H

s

>

0

00s

8

0

B

@

1

C

A

ð1Þ

with the corresponding resistivity tensor being given

by

q ¼

r

>

r

H

0

r

H

r

>

0

00r

8

0

B

@

1

C

A

ð2Þ

The tensor elements

>

and r

8

are called transverse

and longitudinal electrical resistivity, respectively,

with their average

%

r ¼

2

3

r

>

þ

1

3

r

8

ð3Þ

giving the isotropic resistivity

. Normalizing r

>

and

r

8

using

leads to the transverse and longitudinal

magnetoresistivity, respectively:

Dr

%

r

>

¼

r

>

%

r

%

r

ð4Þ

Dr

%

r

8

¼

r

8

%

r

%

r

ð5Þ

The difference of these two quantities gives the AMR

ratio

Dr

%

r

¼

r

8

r

>

%

r

ð6Þ

The off-diagonal element r

H

of the resistivity tensor

is called the Hall resistivity and represents the anom-

alous or spontaneous Hall effect (Karplus and Lut-

tinger 1954, Smit 1955). The elements of the

conductivity tensor r are denoted in an analogous

way to those of the resistivity tensor q with the fol-

lowing relationships between the various elements:

s

>

¼

r

>

r

2

>

þ r

2

H

s

8

¼

1

r

8

s

H

¼

r

H

r

2

>

þ r

2

H

ð7Þ

r

>

¼

s

>

s

2

>

þ s

2

H

r

8

¼

1

s

8

r

H

¼

s

H

s

2

>

þ s

2

H

ð8Þ

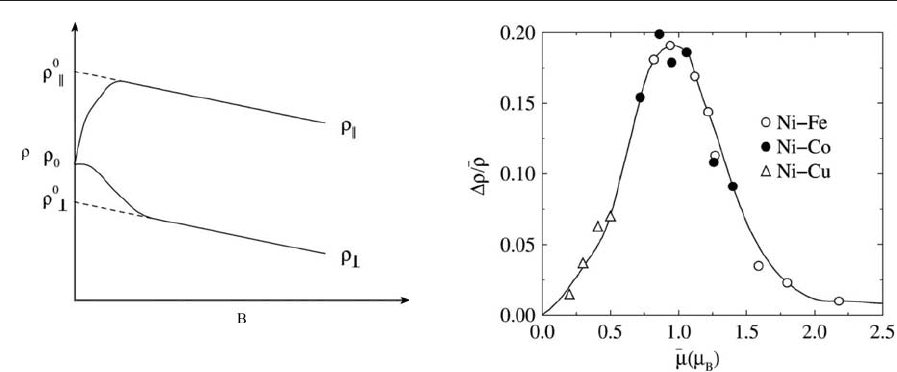

2. Basic Properties

In principle, the above definitions apply to a single-

domain sample. For a multidomain sample one

therefore has to apply an external magnetic field to

align the magnetization. This may lead, for example,

to a variation of r

>

and r

8

with the field, as shown in

Fig. 1 (van Elst 1959). Because the ordinary magne-

toresistance is superimposed onto the spontaneous

magneto-resistance the proper values r

0

>

and r

0

8

, cor-

responding to the single-domain state of the sample

are obtained by an extrapolation of the high-field

data to zero external field.

The simple form given above for the conductivity

and resistivity tensors is not restricted to isotropic

materials, but applies to any material for which the

direction of the magnetization coincides with an at

least three-fold rotational symmetry axis (Kleiner

1966, Cracknell 1973). Furthermore, it can be applied

without modifications for polycrystalline materials.

For less symmetric situations the shape of the tensors

in Eqns. (1) and (2) will change. In particular, for

single crystals one finds that the AMR varies if the

818

Magnetoresistance, Anisotropic

orientation of the magnetization with respect to the

crystal axis is changed (Becker and Do

¨

ring 1939).

3. Materials and Applications

The AMR effect can be observed in principle in any

spontaneously magnetized material. However, most

experimental work has been devoted to systems based

on the transition metals iron, cobalt, and nickel. In

the search for materials with high AMR ratio, diluted

and concentrated alloys among these elements, but

also with other transition metals (e.g., chromium,

vanadium, copper, palladium, and platinum) or non-

transition elements (e.g., aluminum, silicon, tin) have

been investigated (McGuire and Potter 1975,

Dorleijn 1976). Among these systems the highest val-

ues for the AMR ratio Dr/

have been found for

nickel-based alloys.

In particular, a rather simple empirical relationship

between the AMR ratio Dr/

and the average mag-

netic moment m has been found for concentrated bi-

nary nickel-based alloys (see Fig. 2 and below). This

relationship implies that the AMR ratio can be opt-

imized within certain limits by a suitable choice of the

alloy partners and their concentration. An upper

limit seems to be given by the data for NiCo alloys

and NiFeCo alloys, which show AMR ratios of up to

30% at low temperatures. Unfortunately, the AMR

ratio rapidly decreases with increasing temperature.

For example, for Ni

81

Fe

19

one has Dr/

¼20% at

T ¼20 K, but only about 3% at T ¼300 K.

The AMR effect has also been investigated for

a number of amorphous alloy systems, e.g., Fe–Si,

Fe–Zr, and Fe–V–B. These amorphous systems

are attractive because they can be easily prepared as

thin films by various techniques and because their

isotropic resistivity

is in general almost temperature

independent (see Amorphous Intermetallic Alloys: Re-

sistivity). Unfortunately,

is normally quite high (of

the order of 100 mO cm) leading to AMR ratios that

are usually not much higher than 1%. In contrast to

this property of transition metal-based amorphous

systems, a very pronounced AMR effect with Dr/

up

to 26% at low temperature has been found for ferro-

magnetic amorphous alloys based on uranium and

antimony (Freitas and Plaskett 1990). This finding

can be ascribed to the strong spin–orbit coupling of

uranium (see below).

Although the maximum AMR ratio that can be

achieved at room temperature is relatively small, it is

nevertheless high enough to be exploited in sensor

and storage technology (Go

¨

pel et al. 1989). Transi-

tion metal alloys are very suitable for this purpose,

because they can easily be prepared by evaporation

or sputtering deposition as thin films. In some cases

the resistivity

of such films can be decreased by up

to 30% by tempering. This increases the AMR ratio

accordingly leading to a higher output signal for a

given input power (Butherus and Nakahara 1985).

Further important restrictions for applications are a

low magnetostriction and a small coercivity field.

These requirements are extremely well fulfilled by

permalloy that is free of magnetostriction at 81 at.%

nickel. In addition, it has at this composition a very

low coercivity field of about 100 Am

1

and a low

uniaxial anisotropy energy constant of about

200 Jm

3

. Although the AMR ratio for the NiFe–

alloy system is highest for about 90 at.% nickel and

although higher values for Dr/

are achieved by other

transition metal alloy systems (see above), these suit-

able properties make Ni

81

Fe

19

permalloy the most

Figure 2

AMR ratio Dr/

at 20 K as a function of the average

magnetic moment

%

m for various 3d element alloys (after

Wijn 1991).

Figure 1

Dependency of the transverse and longitudinal electrical

resistivity, r

>

and r

8

, respectively, on an external

magnetic field, B.

819

Magnetoresistance, Anisotropic