Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Magnetic Systems: Disordered

All real magnetic materials are imperfect to some ex-

tent; there are static structural imperfections either on

the atomic level (impurity atoms substituted on host

sites in an otherwise perfect lattice) or in the form of

extended defects (dislocations, grain boundaries, or

rough surfaces). The degree of imperfection can be

very low, as in high-quality magnetic monocrystals or

films, or it can be very high, as in certain concen-

trated alloys or in amorphous materials. ‘‘Disorder’’

in the present context can mean a wide distribution of

magnetic couplings between local moments because

of random environments. It can also mean random

local crystal fields—broadly, the interaction between

the effective electric charges on the atoms surround-

ing a magnetic site and the nonspherical charge dis-

tribution of the electrons on the site. Moderate

disorder in ferromagnets has an essential influence on

the hysteresis effects that are intrinsic to the techno-

logically vital hard ferromagnets and magnetic mem-

ory materials.

Here we will first consider the limit of strong cou-

pling disorder, which leads to behavior where the

standard ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism is re-

placed by ‘‘spin glass’’ ordering, with totally novel

behavior. Such strongly disordered magnetic systems

have no direct practical applications but they show

fascinating thermodynamic behavior which poses

conceptually tough problems. The models that have

been developed to understand strongly disordered

magnetism have been widely extended to provide par-

adigms for complex systems of all types–structural,

biological, or sociological. Spin-offs resulting directly

from the ideas arising from the magnetic problems

include sophisticated numerical optimization methods

and neural network computers.

1. Spin Glass Materials

Historically, the spin glass phenomenon was first dis-

covered in the magnetism of dilute alloys; it is char-

acterized by remarkable magnetic irreversibility and

relaxation properties. In certain alloys such as AuFe

or CuMn the transition metal atoms are distributed

at random and have localized magnetic moments

down to very low concentrations (van den Berg

1961). In these alloys the magnetic interactions be-

tween the local spins are through the Ruderman–

Kittel (RKKY) polarization of the conduction elec-

tron band (for RKKY interaction see Magnetism in

Solids: General Introduction). This polarization oscil-

lates in sign as a function of the distance between the

spins, so in a random dilute alloy some pairs of spins

will be coupled ferromagnetically and others antif-

erromagnetically, meaning that the interactions are

quasi-random with both signs present. There is there-

fore strong disorder in the couplings. If a sample of a

few percent concentration of magnetic sites is cooled

slowly and the low-field a.c. susceptibility is meas-

ured, there is a well defined sharp susceptibility cusp

as a function of temperature at a critical temperature

T

g

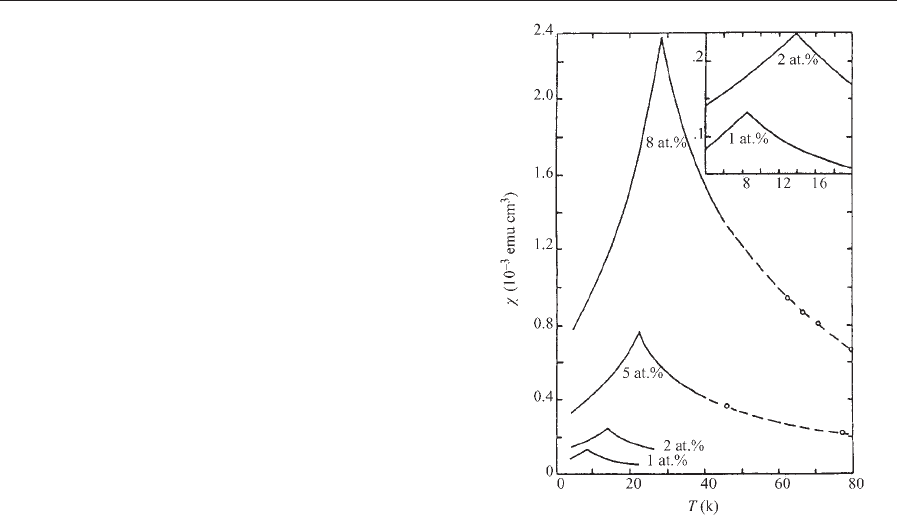

, (Cannella and Mydosh 1972) (Fig. 1), while para-

doxically there is no sign of any singularity any-

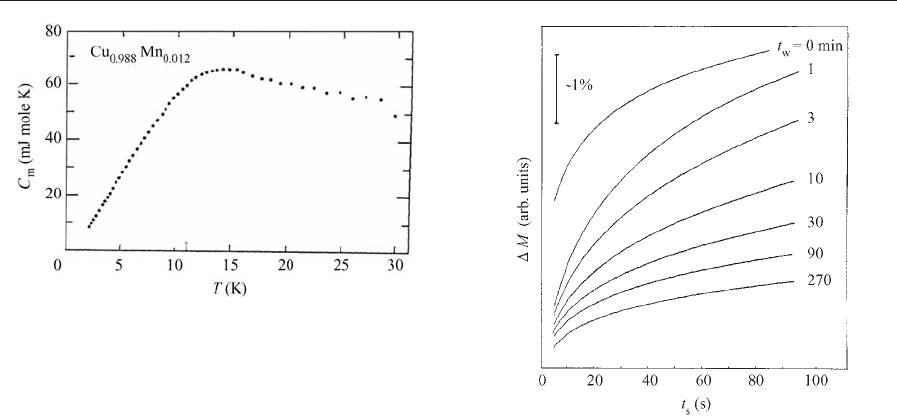

where in the specific heat (Keesom and Wegner 1976)

(Fig. 2).

If the same sample is cooled slowly in a constant

low magnetic field H (field-cooled, FC), a tempera-

ture-independent magnetization plateau develops be-

low T

g

. If, instead, the sample is first cooled in zero

field down to a low temperature (zero-field-cooled,

ZFC), after which the same low field H is applied as

before and then the temperature is raised slowly, the

magnetization is lower than the FC case until the

two curves meet at T

g

. Typically T

g

is of the order

of 10 K for a sample with 1% magnetic impurities

and is roughly proportional to the magnetic site

concentration.

2. Dynamics and Critical Behavior

Over the whole range of temperatures above T

g

re-

laxation is paramagnetic; the sample has an induced

magnetization in an applied field, and when the field

Figure 1

Low-field a.c. susceptibility of AuFe alloys 1–8 at.% Fe

in a 5 gauss field at E 100 Hz frequency. The cusps are

clearly defined. (Reproduced by permission of American

Physical Society from Phys. Rev. B 1972, 6, 4220.)

690

Magnetic Sys tems: Disordered

is cut off the magnetization drops to zero in a short

but finite time. The form of the relaxation decay be-

comes strongly nonexponential as T

g

is approached,

and the relaxation times, while still much shorter than

a second, become very long compared with atomic

relaxation timescales which are of the order of a pi-

cosecond (Mezei and Murani 1979).

Things are very different below T

g

. If the sample is

cooled in field to a temperature T below T

g

and the

field is then cut off, there is a residual magnetization

M which decays slowly and quasi-logarithmically

with time t, i.e.,

MðtÞBMð0ÞS logðtÞð1Þ

over many decades in t (Guy 1978). This ‘‘magnetic

creep’’ signifies that as time passes the relaxation be-

comes slower, and on all practical time scales (maybe

even to millions of years) the residual magnetization

will never decay to zero.

The difference between behavior above T

g

and be-

low T

g

is dramatic. Just above T

g

relaxation is meas-

ured in microseconds while below T

g

there is a huge

range of effective time scales, extending through years

to infinity.

In fact, quasi-logarithmic relaxation below T

g

is

simply a convenient approximation. S is not a con-

stant, and the form of the relaxation expressed in

terms of S(t) has been studied in great detail. There

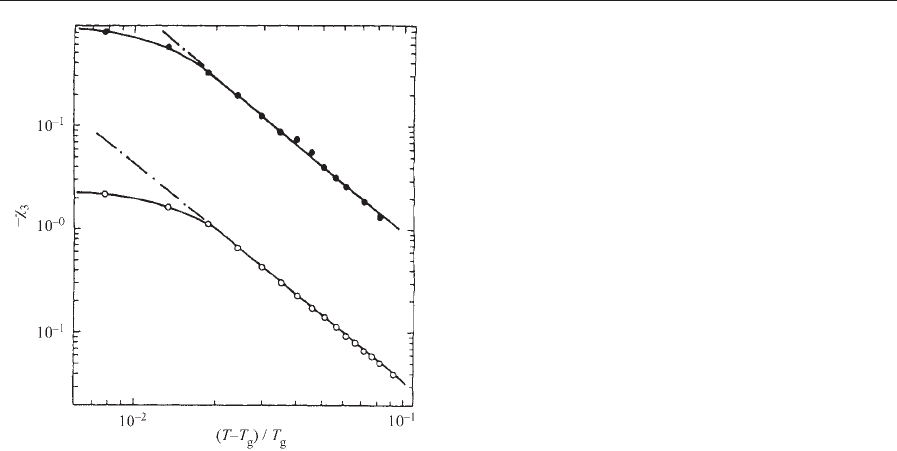

are striking aging effects in the low-temperature re-

laxation (Lundgren et al. 1983): if the sample is field-

cooled to T and then held at constant temperature for

a ‘‘waiting time’’ t

w

before the field is cut off (or

alternatively if the sample is zero-field-cooled and

then a field is applied) the relaxation of the magnet-

ization depends on how long the waiting time is, as

shown in Fig. 3. There is a cryptic reorganization of

the spins during the waiting. A related measurement

is magnetic torque; if the sample is field-cooled to T

and then the field is rotated by a small angle, the

magnetization does not follow the field but a torque

signal appears. (A torque signal is equal to the vector

product of magnetization and field). The origin of

this torque is closely related to a local anisotropy, a

specific spin glass characteristic. The fact that torque

is observed is again a consequence of the memory of

the spin system; if the spins could reorganize freely

there would be zero torque.

Accurate measurements of the a.c. susceptibility in

the region of the cusp show slight frequency-dependent

effects: the smaller the frequency the lower the appar-

ent cusp temperature. (Typically the change in the

apparent T

g

is 0.1% for a decade change in excitation

frequency, so this is a small effect). The change in

T

g

could suggest that the cusp is not the signature

of an onset of ordering but just an artifact related

to a continuous and gradual slowing down of relax-

ation. However, careful experiments have shown that

the static magnetization of the spin glasses has a

critical behavior with well-characterized expo-

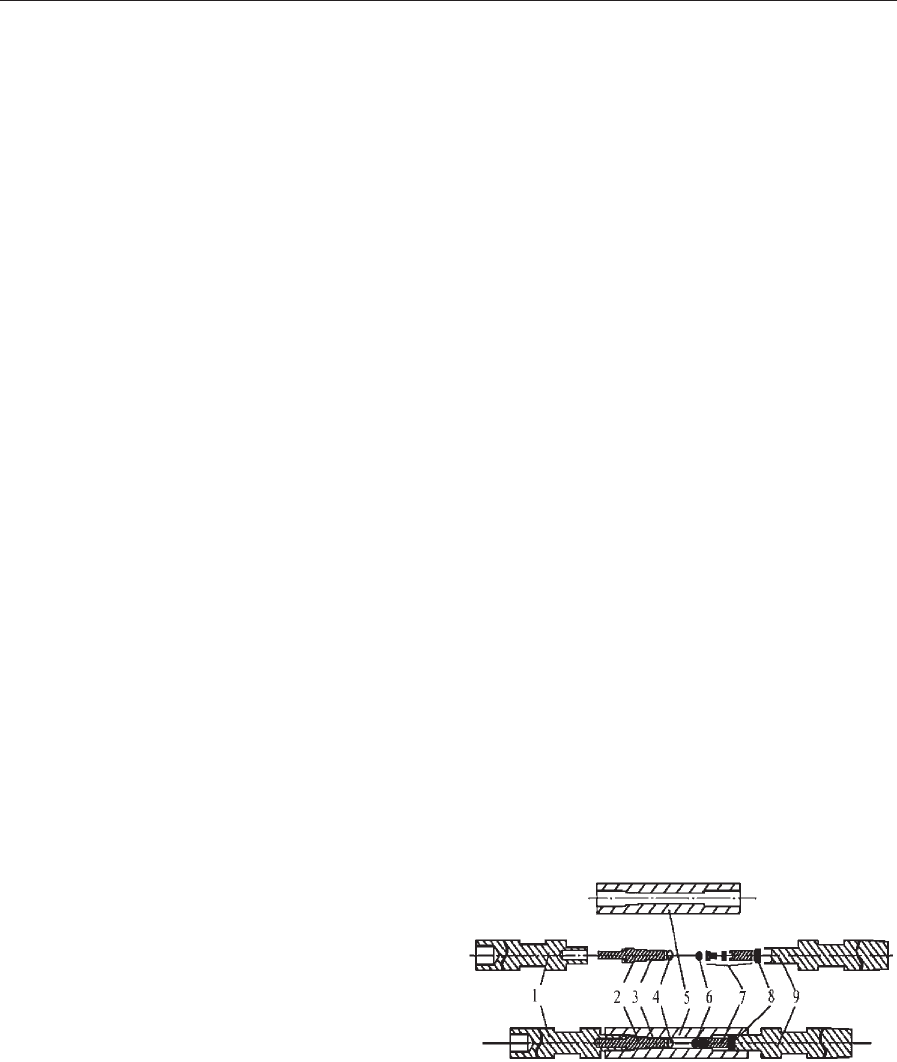

nents (Bouchiat and Monod 1983, Le

´

vy 1988), as in

Figure 3

Relaxation in the frozen state of Cu–4 at.% Mn alloy.

After cooling the sample in zero field to a temperature of

0.88 times the freezing temperature, a small field

(1 gauss) is applied following a waiting time t

w

. The

relaxation of the resulting magnetization is measured for

100 sec after switching on the field. It can be seen that

there is always a slow creep-like relaxation, and that this

relaxation changes dramatically with the waiting time.

(Reproduced by permission of American Physical

Society from Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 911.)

Figure 2

Magnetic specific heat for a Cu–1.2 at.% Mn alloy. The

arrow at about 11 K indicates the susceptibility cusp

temperature; there is no sign of any accompanying

specific heat anomaly. (Reproduced by permission of

American Physical Society from Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13,

4053.)

691

Magnetic Systems: Disordered

standard econd-order transitions (Fig. 4). Suppose we

measure the reversible magnetization above T

g

and

write the magnetization M as a function of applied

field H in a Taylor expansion where there are only odd

terms because of time reverse symmetry, the following

expression is obtained:

MðT; HÞ¼w

1

ðTÞH þ w

3

ðTÞH

3

þ y ð2Þ

Then the linear susceptibilityw

1

(T) does not diverge

at T

g

while the nonlinear susceptibility w

3

(T) does

diverge, as 1/(TT

g

)

g

. This important observation

(where no time dependence is involved) demonstrates

that T

g

is a bona fide thermodynamic transition tem-

perature and not just a crossover temperature sepa-

rating a rapid relaxation regime from a slow

relaxation regime. The time dependencies observed

in a.c. measurements arise because the response of the

sample to a change of field has a very wide range of

characteristic timescales when the temperature is

close to the ordering temperature.

A remarkable fact is that despite the struc-

tural randomness (which implies that the effective

concentration changes from one microscopic region

to another) the freezing transition is sharp and there-

fore must be a long-range cooperative phenomenon.

The numerical values of the critical exponents

(such as g) are quite different from those seen at sec-

ond-order transitions, magnetic or otherwise, in reg-

ular materials. Two examples are the critical

exponent a for the specific heat, and the dynamic

exponent z. In regular materials a is usually very near

zero, which corresponds to a sharp maximum (or

even a divergence) in the specific heat as the transi-

tion temperature is passed. In the spin glasses a is

typically 2, which corresponds to a complete lack of

singularity in the specific heat at the transition. Con-

cerning the dynamics, in canonical systems zE2 while

in spin glasses zE6. This means that there is an ex-

ceptionally wide regime of temperature above the

transition in spin glasses where the dynamics are

slowing down.

What is the physics behind the spin glass behavior?

Because there is long time irreversibility below T

g

the

material appears to be in an ‘‘ordered’’ state, as a

paramagnetic state only has reversible behavior by

definition. The question is: What does ‘‘ordered’’

mean? The spin glass ordering represents a freezing of

the spins into a cooperative configuration that opt-

imizes the overall energy by satisfying as many indi-

vidual pair interactions as possible. Because there are

many configurations which minimize global energy

almost equally well, we have all the complicated dy-

namics both above and below the ordering temper-

ature. The necessary condition for spin glass order to

exist would appear to be a combination of a certain

degree of randomness (the random positions of the

spins in the dilute alloy case) and conflicting interac-

tions (here due to the RKKY oscillations).

In practice the conditions of randomness and con-

flict appear to be quite commonplace in magnetic

materials, as many hundreds of experimental mate-

rials, both metallic and insulating, show the same

canonical behavior. As well as the dilute alloys AuFe,

CuMn, AgMn, AuCr, or AlGd there are other alloys

such as NiMn over an intermediate range of concen-

tration, Eu

x

Sr

1–x

, amorphous alloys such as NiFe(P-

BAl) or FeMnP, insulators such as CdCr

1.7

In

0.3

S

4

,or

semiconductors such as Cd(Mn)Te. Common signa-

tures characteristic of all spin glasses are the magnetic

irreversibility onset below T

g

, a lack of any singular

feature in the specific heat at T

g

, and slow nonexpo-

nential relaxation of the residual magnetization, with

aging, below T

g

(Mydosh 1993).

To understand what is happening it is useful to

compare the results in model systems.

3. Model Systems

The simplest of all model systems for magnetic or-

dering is the pure Ising ferromagnet, originally studied

Figure 4

Temperature dependence of the nonlinear susceptibility

w

3

in a AgMn–0.5 at.% sample above the freezing

temperature. Measurements made at 0.01 Hz. Open

symbols: zero static applied field; closed symbols: 90

gauss static applied field. The straight line on the log–log

plot is the canonical signature of critical behavior at the

approach to a transition temperature. The bend over

very close to the ordering temperature is a critical

slowing down effect. (Reproduced by permission of

American Physical Society from Phys. Rev. B 1988, 38,

4983.)

692

Magnetic Sys tems: Disordered

by Ising in his thesis in 1925, and solved exactly in

dimension two by Onsager 15 years later (for the Ising

model see Magnetism in Solids: General Introduction).

Ising spins (the spin directions are restricted to be only

up or down) are placed on a regular lattice with in-

teractions of strength J between each pair of near

neighbors. In the paramagnetic state the spins flip

from up to down and there is no global magnetiza-

tion. When the temperature is lowered through a crit-

ical temperature T

c

there is a spontaneous ‘‘symmetry

breaking’’; the spins all conspire to choose an overall

magnetization direction, with a majority of spins

pointing either up or down. When the same system is

cooled down a number of times it chooses up or down

at random each time, but for temperatures less than

T

c

, once the magnetization direction is decided after a

given cooling it stays fixed. Temporary correlated

clusters of spins of the same sign form and grow as T

c

is approached from above, and the timescale for mag-

netization fluctuations diverges as the temperature

tends towards the critical temperature. All the ther-

modynamic and statistical properties of this system

are now extremely well understood thanks to the re-

normalization group theory (Wilson 1975).

This is a pure ferromagnetic Ising system. But what

about disorder? The simplest type of disorder that

can be introduced is dilution. Suppose that some of

the spins are taken away at random, leaving a frac-

tion p of occupied sites. It turns out that this does not

affect the system in a very fundamental way. As could

be expected the ordering temperature T

c

(p) drops as p

decreases, tending to zero at a critical value p

c

; this

corresponds to a ‘‘percolation’’ limit. When there is

no longer a giant cluster of spins all linked together

by near-neighbor interactions there will no longer be

an ordered state even at zero temperature. However,

the properties at the transition, such as the peak in

the specific heat and the divergence of the suscepti-

bility at T

c

, remain very similar to those in the pure

system from p ¼1 down to p ¼p

c

.

Instead of dilution, the spin glass situation with

both ferro and antiferro interactions can be mimicked

by a regular lattice of Ising spins where the near-

neighbor interactions are chosen randomly to be

positive or negative ( J or þJ). This is much more

drastic, as now half the pairs of spins want to be

aligned parallel to each other and half antiparallel,

giving strong frustration. It turns out that this model,

the Edwards–Anderson model (Edwards and Ander-

son 1975), defined in a couple of lines, is extremely

hard to solve theoretically, and for dimension three

most of what is known comes from large-scale nu-

merical simulations. (It is interesting to compare with

the Japanese game of Go, which has trivially simple

rules involving black and white pieces like up and

down spins, and which is also of extreme complexity.)

The mean field limit (corresponding to an infinite

space dimension where all spins are neighbors to all

other spins) has been solved by Parisi (1983) thanks

to a mathematical tour de force. It turns out that

there is a huge number of inequivalent ground states,

so the system must choose not just between two al-

ternatives (global magnetization up or down) as in

the ferromagnet case but between very many inequiv-

alent complex arrangements of spins, all of which

manage to minimize the total energy.

For spin glasses in finite dimensions (such as the

real-world dimension three) it is still not clear if the

physics is strictly the same as in the mean-field sit-

uation, but there are certainly huge numbers of either

ground states or very long-lived metastable states,

which are almost the same for practical purposes. The

numerical data show that there is an ordered low-

temperature state as in the experimental spin glass,

where the word ‘‘ordered’’ has a special sense. In a

standard ferromagnet or antiferromagnet the order

parameter is the overall magnetization or staggered

magnetization, respectively; for the spin glass there is

no equivalent.

The order parameter is defined as the memory

function averaged over time and over the spins:

q

EA

¼½/S

i

ðtÞS

i

ðt

0

ÞSð3Þ

where /yS means a time average for spin S

i

and

[y] means an average over all spins. The difference

between times t and t

0

is chosen to be arbitrarily long

and the system contains many spins. If globally the

spins have an infinitely long memory time for their

individual orientations, at time t

0

each spin i has a

probability of 40.5 to have the same orientation as it

had at time t, however long is [t

0

t]. The spins ‘‘re-

member’’; this defines the system as being frozen and

so ‘‘ordered’’, and q

EA

a 0. The name ‘‘spin glass’’

coined in 1970 by Coles and Anderson (Anderson

1970) expresses the fact that the difference between

the paramagnetic state and the ordered state is ba-

sically one of timescale, just as the difference between

a liquid and a structural glass cannot be seen from the

atomic position (there is no long-range atomic order

in either case) but from the timescale of the atomic

movements which is short in the liquid and infinitely

long in the glass. This does not imply that the change

in timescale is continuous as a function of tempera-

ture; at the ordering temperature the autocorrelation

timescale diverges.

A great deal of information can be obtained from

the numerical simulations, which are well adapted to

the problem as Ising spins are good binary objects.

As the spin ensemble is cooled down (according to

standard numerical procedures) relaxation becomes

slow and highly nonexponential, meaning that there

is a very wide range of effective relaxation times

(Ogielski 1985). The transition temperature can be

defined by the divergence of the mean relaxation

time, or through techniques using scaling rules ap-

plied to numerical samples of finite but progressively

increasing size. Like in the experimental case there is

693

Magnetic Systems: Disordered

a well-defined transition with critical behavior, and

again as for the experimental materials no visible

singularity in the specific heat is observed at the

transition. The frustration reduces the ordering tem-

perature compared with the ferromagnetic case; for a

three-dimensional ferromagnetic system with interac-

tion strength J the ordering temperature is 4.51 kJ.

For a spin glass on the same lattice with interactions

randomly þJ and –J, the freezing temperature is

near 1.2 kJ. In dimension two, the ferromagnetic or-

dering temperature is 2.27 kJ (Onsager 1944) while

the spin glass does not order until zero temperature

(Binder and Young 1986).

There are several experimental materials that are

quasi-Ising. These systems have dilute, randomly dis-

tributed magnetic sites in a crystal structure with an

axial symmetry such that there are strong local crys-

tal fields acting on the spins, all parallel to the sym-

metry axis. If the local moments are all constrained to

be parallel or antiparallel to the axis, then the ma-

terial behaves essentially as an Ising spin glass. Ex-

amples are the three-dimensional mixed compound

Fe

0.5

Mn

0.5

TiO

3

(Ito et al. 1986) and the two-dimen-

sional layer compound Rb

2

Cu

1–x

Co

x

F

4

(Dekker

et al. 1988). Numerical and experimental values for

properties such as the critical exponents can be com-

pared, and good agreement has been found.

All the major features of the behavior of the ex-

perimental spin glasses are reproduced by the nu-

merical simulations. For instance, the relaxation

behaviors observed experimentally below and above

T

g

are seen with essentially the same form in the

simulations. The agreement between the experiments

and the simulations (which, it must be remembered,

are done on very simplified model systems) and the

fact that experimental systems behave similarly to

each other means that all these phenomena are in-

trinsic to the glassy type of ordering, and that the

details of the interactions, the types of spins, and so

on are fairly irrelevant. The numerical work can

give access to parameters that are very hard to see

experimentally such as the particular microscopic

configuration taken up by the spins. Most remarka-

bly, each time a large system is cooled down, it ends

up in a microscopically different frozen state. There

indeed appears to be a quasi-infinity of low-temper-

ature configurations by which the spin ensemble

can satisfy the frustrated interactions almost equally

well. Instead of the system breaking symmetry by

choosing between up and down global magnetization

as in the ferromagnetic case, it breaks it in a funda-

mentally different way by choosing from among an

enormous number of alternative complex inequiva-

lent configurations.

Numerical studies of spin glasses are extremely

time-consuming because of the long relaxations, and

subtle difficulties appear. As a result, the ordering

temperatures of the canonical models in dimension

three are still not accurately determined even after

more than 20 years of intensive numerical effort, and

the correct description of the ordering process in

finite dimensional spin glasses is still a hotly debated

topic.

Finally, in the vast majority of experimental spin

glass materials, the spins are Heisenberg (for a de-

scription of the Heisenberg model see Magnetism in

Solids: General Introduction) rather than Ising, which

means that the spin can take any orientation in space,

not just up and down. Numerical simulations with

this type of spin indicate clearly that if the mechanism

of the ordering were the same as for Ising spins, then

T

g

should be zero in dimension three. The most

plausible explanation for this paradox (we certainly

know from experiment that spin glasses with finite

ordering temperatures exist in real-life three-dimen-

sional materials) is that the ordering is fundamentally

‘‘chiral,’’ which corresponds to a three-spin corre-

lation function for Heisenberg spins rather than a

two-spin exchange interaction. The numerous conse-

quences of this model (Kawamura 1992) are still

being studied.

The spin glass is not simply a thermodynamic cu-

riosity. It should provide the most tractable example

of the vast family of complex systems with disorder

and frustration, which includes glasses of all kinds,

and optimization problems such as the famous trav-

elling salesman problem. Neural computing tech-

niques are directly inspired by spin glass work. The

spin glass has become a paradigm for the behavior of

complex cooperative systems in general, from the

stock market to the genetic code; however, it turns

out that the physics of even the simplest model spin

glass is extremely subtle and is not yet fully under-

stood. An enormous experimental and theoretical ef-

fort has gone into the study of spin glasses over the

last 30 years, but only a few definitive answers have

been given in response to the many questions that

arise.

4. Reentrant Magnetism

In certain alloy series, the nature of the ordering

changes from ferromagnetic to spin glass as a func-

tion of concentration. AuFe alloys are ferromagnetic

from pure Fe down to 15% Fe concentration, while

for lower Fe concentrations they order as spin glass-

es. Clearly this behavior corresponds to a conflict

between a ferromagnetic ordering tendency when the

near-neighbor ferromagnetic interactions dominate

and the random interaction spin glass case for dilute

spins. There are many other experimental examples

of this behavior (e.g., (Campbell and Senoussi 1992).

Very early on in the model calculations, the Ising

system with near-neighbor interactions was studied

for a fraction p of ferromagnetic interactions and

(1p) antiferromagnetic interactions (p ¼0.5 is of

course the standard spin glass that is discussed

694

Magnetic Sys tems: Disordered

above). At a critical intermediate concentration p

n

the order passes abruptly from spin glass to ferro-

magnetic, much as in the experiments. However, the

behavior seen in real materials where the spins are

Heisenberg rather than Ising is subtler. There is again

a critical concentration p

n

but on the ferromagnetic

side of p

n

‘‘reentrant’’ behavior is found. Suppose we

have a sample on the ferromagnetic side of p

n

.We

cool it down slowly starting from high temperatures.

We will first encounter an ordering temperature T

c

below which the order is conventional ferromagnet-

ism. However, at some lower temperature T

k

‘‘can-

ting’’ sets in; i.e., each spin has a frozen component

M

z

along the overall magnetization axis as in a ferro-

magnet, but it also has frozen components M

x

and

M

y

in the plane perpendicular to the z axis.

These perpendicular components are quasi-ran-

dom, so the spin system has found a compromise

between ferromagnetism and spin glass ordering by

having a novel type of magnetic structure where or-

dering of both types is superimposed. In a sense the

spins are ferromagnetic as far as their z components

are concerned but spin glass for their x,y compo-

nents. The onset of the canted state has important

consequences for the macroscopic magnetic proper-

ties of the sample. The a.c. susceptibility can be high

between T

c

and T

k

but drops drastically at temper-

atures below T

k

because the canting induces a block-

ing of the domain wall movements.

5. Random Anisotropy

Local magnetic moments are influenced not only by

the exchange interactions with their neighbors but

also by local effective crystal fields if their magnetism

has an orbital component. In a perfect lattice there

are already global anisotropies due to local crystal

fields with the point symmetry of the lattice site (for

crystal field and anisotropy see Magnetism in Solids:

General Introduction, Localized 4f and 5f Moments:

Magnetism). For instance, in a hexagonal site a local

moment will generally prefer to align either parallel

or antiparallel to the hexagonal axis, while in a cubic

site there are higher-order anisotropy terms which

favor specific crystal axes, for instance /111S. If the

crystal is made up of a random alloy of atoms A and

B, individual atoms will have different local environ-

ments depending on how many of each type of

neighbors it has and what neighbor sites they occupy.

Atoms A and B have different effective charges, so

each magnetic lattice site will have a local low-sym-

metry crystal field in addition to the regular crystal

field arising from the crystal structure.

The orientation and strength of this local crystal

field depends on the exact local environment created

by the neighboring atoms; this situation is referred to

as ‘‘random anisotropy.’’ A given atomic moment

can prefer to align along one space direction while

another atom prefers a different direction. These an-

isotropy terms can be strong or weak, depending

mainly on the type of magnetic atom as well as on the

degree of disorder of the environment. Atoms such as

Gd or Mn which have very small orbital moments are

hardly influenced by the crystal fields, while other

rare-earth atoms with strong orbital magnetism may

be strongly affected in the same system. For a ferro-

magnetic alloy in presence of these random anisotro-

pies, the local magnetic moments will be submitted to

contradictory influences—the exchange interactions

with the neighbors will tend to align the moments all

the same way while the random anisotropies will try

to force each moment to remain pointed along its

local anisotropy axis.

Extreme cases are provided by amorphous alloys

of rare earths. Because of the surrounding amor-

phous structure, rare-earth environments have very

low symmetry. To a good approximation each rare-

earth atom is submitted to a strong axial crystal field

with the directions of the axes varying randomly from

site to site. (The fact that the effective local crystal

field is axial rather than planar can be shown to be a

consequence of the high spins of the rare earths).

When the exchange interactions between the mag-

netic sites are ferromagnetic, the moments freeze

below an ordering temperature to form a ‘‘spero-

magnetic’’ structure: instead of all moments being

aligned parallel, the moment directions fan out over

a hemisphere (see Amorphous and Nanocrystalline

Materials).

6. Random Fields

Model systems have been studied where each site is

submitted to a random local magnetic field instead of

a random anisotropy. A random local field does not

have the same effect as a random axial anisotropy.

With the latter the local moment has two equally fa-

vorable low-energy configurations, along the axis in

the up or down direction. A random field favors one

particular direction only. In the Random Field Ising

Model (RFIM) (Imry and Ma 1975, Young 1997)

random local fields of strength þ/h act on each

spin in an Ising ferromagnet. We know that Ising

spins with ferromagnetic interactions on a two-

dimensional lattice order ferromagnetically with a fi-

nite T

c

. It can be demonstrated that for a large sam-

ple in dimension two, with ferromagnetic exchange

interactions and random magnetic fields, the overall

ferromagnetic order is destroyed even for weak h,as

it is always energetically favorable for the system to

break up into domains which organize themselves in

such a way as to maximize the gain in energy from

interaction with the field. For dimension three, ferro-

magnetism persists for small h, but is destroyed

when h/J passes a critical value. (It is clear that when

the random field term is much stronger than the

695

Magnetic Systems: Disordered

spin–spin interaction term each spin will tend to align

along its local field direction and so ferromagnetic

order will be destroyed.) Extensive model calcula-

tions have been made on the dynamics of the RFIM.

At first sight it is not obvious that there is any

physical system which could be considered to be of a

random field nature, as it is not possible to apply

external magnetic fields which change from up to

down on an atomic scale. In practice a physical

equivalent of the model is provided by a diluted

Ising-like antiferromagnet in a uniform applied field.

The canonical example is Fe

x

Zn

1–x

F

2

(King et al.

1986). In the pure compound FeF

2

a large crystal

field anisotropy means that the magnetic Fe moments

have quasi-Ising character; they can point only up or

down in the crystal field direction and the ordering is

antiferromagnetic. When the system is diluted by the

nonmagnetic Zn, in zero field its properties stay very

much the same. However, when a uniform magnetic

field is applied along the crystal field axis, because of

the distribution of local exchange strengths, this leads

physically to a situation which can be mapped pre-

cisely on to that of a ferromagnet in a random field.

The critical behavior has been very carefully studied

by a variety of techniques to check the RFIM pre-

dictions. As in spin glasses the critical dynamics at the

RFIM are extremely slow, and in the ordered state

are governed by pinning from the random field fluc-

tuations or by vacancies.

7. Disorder in Ferromagnets and Hard Magnetism

In the previous sections the discussion has centered

on the effects of very strong disorder, which tends to

produce new classes of ordering. Weaker disorder

also has important implications for the magnetic

properties of the ferromagnets that are of extreme

importance in today’s technologies.

In zero magnetic field it has been considered above

that a ferromagnet sample will order with all its spins

parallel, either up or down. This is an idealized pic-

ture as a number of ingredients have been left out. An

ideal theoretician’s ferromagnet has only exchange

interactions between spins and geometrical effects do

not play a role; for a real-life ferromagnet it is im-

portant for instance also to take into account clas-

sical dipole energy terms. Although these are many

orders of magnitude weaker than the exchange terms,

they are long-range and strongly influence the overall

magnetization arrangements in all but nanoscopic

ferromagnetic samples. For general sample geome-

tries the minimum energy magnetic configuration has

a domain structure with domains of parallel spins

having domain walls separating them.

The width of the domain wall depends on the in-

terplay between exchange terms and anisotropy or

magnetostriction terms. Consider a ferromagnetic

monocrystal. Because of anisotropy (and to some

extent magnetostriction) there are preferential crystal

directions for the domain axes. We will discuss a

particularly simple case. Imagine we have a single

crystal with axial symmetry (e.g., hexagonal) and

with the macroscopic anisotropy favoring magneti-

zation either parallel or antiparallel to the z axis. A

typical magnetic configuration could be an up do-

main ( þz orientation) and a down domain (z ori-

entation) separated by a single domain wall

perpendicular to the z axis. Within the domain wall

the spin directions will turn progressively from þz to

z, swinging through some direction in the x,y plane

at the center of the wall.

The width of the domain wall will depend on the

ratio of anisotropy to exchange. When anisotropy is

weak, the local magnetization direction can turn

gradually so as to minimize the cost in exchange en-

ergy (neighboring spins within the domain wall will

not be at a large angle with respect to each other if

the wall is wide). We will have very broad domain

walls, many hundreds of atoms thick. On the con-

trary, when the anisotropy is strong, the domain wall

must stay narrow; the spins must turn within a short

distance so as to incur as small a cost as possible in

the anisotropy energy corresponding to the spins in

the center of the wall which are necessarily oriented

in the x,y plane, the unfavorable direction with re-

spect to the anisotropy. The domain wall will be nar-

row, in extreme cases only a few atomic layers thick.

Now if a magnetic field is applied, the domain wall

will tend to move so that the domain with its mag-

netization parallel to the field can grow. When the

domain wall is wide, any local defects will have little

effect as it is the average energy over the whole wall

that counts, so the energy of the wall will depend little

on its exact position. Local disorder on the atomic

scale will have little influence on such a broad domain

wall, as any energy terms will be averaged over the

whole width of the wall. Soft magnetic alloy mate-

rials, with carefully tailored compositions chosen to

minimize hysteresis, can be concentrated alloys (such

as mumetal) or amorphous transition-metal ferro-

magnets, without the strong local disorder reducing

significantly their high domain wall mobilities be-

cause it is a homogeneous disorder.

Mobility is reduced and the soft magnetic proper-

ties are adversely affected by more macroscopic

forms of disorder such as dislocations, which can

pin the domain wall efficiently as they influence the

wall energy on a much larger spatial scale. As a con-

sequence, structural damage (such as cold work) can

spectacularly diminish the high permeability of soft

magnetic materials.

However, when the wall is narrow a few defects

(even very local defects such as vacancies) can have a

strong influence on the wall energy. In a matrix with

defects there will be optimal positions for the wall, or

in other words the wall will tend to be ‘‘pinned.’’ For

a sample with wide walls that can move easily the

696

Magnetic Sys tems: Disordered

response to the applied field is almost reversible; the

materials are magnetically soft, with low hysteresis

and high permeability. On the other hand, when walls

are narrow and can be easily pinned the material will

have high hysteresis and a strong residual moment.

These are just the characteristics required for perma-

nent magnets, i.e., for ‘‘hard’’ magnetic materials.

The conditions of high anisotropy-to-exchange ra-

tios and strong pinning are particularly favorable in

rare-earth compounds. The rare earths (except for

Gd) have exceptionally strong orbital moments, and

excellent hard magnetic materials are formed by

many rare-earth–transition-metal compounds, with

interstitial atoms introduced so as to give extra local

crystal fields and to dilate the lattice, which has the

effect of increasing the ordering temperatures. Special

metallurgical techniques are used to produce materi-

als with small grains and high dislocation densities,

all in order to enhance pinning. Of course for engi-

neering applications these materials have to satisfy

many other criteria as well; for example, they must

have a Curie temperature that is as high possible so as

to have useful magnetizations at room temperature,

and they must not corrode.

See also: Magnets Soft and Hard: Magnetic Do-

mains; Coercivity Mechanisms; Magnetic Systems:

Lattice Geometry-oriented Frustration; Nanosized

Particle Systems, Magnetometry on

Bibliography

Anderson P W 1970 Localization theory and the Cu–Mn prob-

lem: spin glasses. Mater. Res. Bull. 5, 549–54

Binder K, Young A P 1986 Spin glasses: experimental facts,

theoretical concepts and open questions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 58,

801–976

Bouchiat H, Monod P 1983 Remanent magnetisation proper-

ties of the spin glass phase. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 30, 175–

91

Campbell I A, Senoussi S 1992 Re-entrant systems: a compro-

mise between spin glass and ferromagnetic order. Phil. Mag.

65, 1267–74

Canella V, Mydosh J A 1972 Magnetic ordering in gold–iron

alloys (susceptibility and thermopower studies). Phys. Rev. B

6, 4220–37

Dekker C, Arts A F M, de Wijn H W, van Duynveldt A J,

Mydosh J A 1988 Activated dynamics in the two-dimensional

spin glass Rb

2

Cu

1–x

Co

x

F

4

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1780

Edwards S F, Anderson P W 1975 Theory of spin glasses. J.

Phys. F 5, 965

Fischer K H, Hertz J A 1991 Spin Glasses. Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, Cambridge

Guy C N 1978 Spin glasses in low dc fields II: magnetic vis-

cosity. J. Phys. F 8, 1309–19

Imry Y, Ma S 1975 Random field instability of the ordered state

of continuous symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 1399–1401

Ito A, Aruga H, Torikai E, Kikuchi M, Syono Y, Takei H 1986

Time dependent phenomena in a short range Ising spin glass,

Fe

0.5

Mn

0.5

TiO

3

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 483–6

Kawamura H 1992 Chiral ordering in Heisenberg spin glasses

in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3785–8

Keesom P H, Wegner L E 1976 Calorimetric investigation of a

spin glass alloy: CuMn. Phys. Rev. B 13, 4053–9

King A R, Mydosh J A, Jaccarino V 1986 AC susceptibility

study of the D ¼3 random field critical dynamics. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 56, 2525–8

Le

´

vy L P 1988 Critical dynamics of metallic spin glasses. Phys.

Rev. B 38, 4963–73

Lundgren L, Svedlindh P, Nordblad P, Beckman O 1983 Dy-

namics of the relaxation time spectrum in a CuMn spin glass.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 51, 911–4

Mezei F, Murani A P 1979 Combined three dimensional po-

larization analysis and spin echo study of spin glass dynam-

ics. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 14, 211–4

Mydosh J A 1993 Spin Glasses. Taylor and Francis, London

Ogielski A T 1985 Dynamics of three-dimensional Ising spin

glasses in thermal equilibrium. Phys. Rev. B 32, 7384–98

Onsager L 1944 Crystal statistics. I. A two dimensional model

with an order-disorder transition. Phys. Rev. 6, 117–49

Parisi G 1983 Order parameter for spin glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett.

50, 1946–8

van den Berg G J 1961 In: Graham G M, Hollis-Hallett A C

(eds.), Proc. Int. Conf. Low Temperature Physics. University

of Toronto Press

Wilson K G 1975 The renormalization group: criticlal

phenomena and the Kondo problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 47,

773–840

Young A P 1997 Spin Glasses and Random Fields. World Sci-

entific, Singapore

I. Campbell

Universite

´

Paris Sud, Orsay, France

Magnetic Systems: External

Pressure-induced Phenomena

Most elements having magnetic moments as free

atoms lose the moment after condensation into sol-

ids; magnetism is retained only in a few rare cases. In

the competition between cohesive and magnetic in-

teractions, the first one wins. Application of high

external pressure to magnetic solids leads to a further

decrease in interatomic distances and generally to a

depression of magnetism. However, under a suffi-

ciently high pressure, some electrons can be removed

from a filled inner atomic shell and an appearance

of new magnetism can reflect a momentary state of

the electronic configuration. A good example of this

phenomenon is metallic ytterbium, which only be-

comes magnetic under high pressure, when one elec-

tron is removed from the originally filled 4f shell (see

Intermediate Valence Systems).

All interactions responsible for magnetism in solids

are sensitive to interatomic distances. Application

of an external pressure leads to variations in these

distances and therefore offers a unique possibility

to study these aspects of magnetism. Experiments

697

Magnetic Sys tems: External Pressure-induced Phenomena

performed under external pressure provide intrinsic

results. These results are not contaminated by para-

sitic effects accompanying the chemical substitutions,

which are widely used to vary the interatomic dis-

tances. The changes of magnetic moments, their ar-

rangement, and the magnetocrystalline anisotropy

induced under pressure are very informative phe-

nomena for both applied and basic studies in solid-

state physics.

1. Theory and Experiments

1.1 Thermodynamic Relations

From the phenomenological point of view, the pres-

sure-induced changes of magnetic properties can be

considered as an inverse effect to the magnetostri-

ction (see also Magnetoelastic Phenomena). Consid-

ering only the isotropic effects, the basic relations can

be derived from the differential of the Gibbs function:

dG ¼SdT MdH þ Vdp ð1Þ

where M is the saturated magnetization of sample of

volume V, parallel to the magnetic field H.

The relation between the magnetostriction and the

pressure changes of the magnetization

dM=dp ¼dV=dH ð2Þ

directly follows from the exact differential dG. Con-

sidering M(T,p) ¼M

0

(0,p)[f(T/T

C

)], the pressure de-

pendence of magnetization can be derived as

dlnM=dp ¼

½dlnM

0

=dp TðdlnM=dT ÞðdlnT

C

=dpÞ

½1 þ 3ða=kÞðdlnT

C

=dpÞ

ð3Þ

where a is the linear thermal expansion coefficient, k

is compressibility and T

C

is the Curie temperature.

Using dlnV ¼kdp and the magnetic Gru

¨

neisen co-

efficient G ¼dlnT

C

/dlnV, the critical pressure P

C

for

the disappearance of the magnetic state in solids is

given by the simple relation

P

C

E T

C

ðdT

C

=dpÞ

1

¼ðkGÞ

1

ð4Þ

To estimate the compressibility in the magnetically

ordered state, the paramagnetic compressibility k,as

a material property connecting the theory and the

experiment, has to be modified by a magnetic con-

tribution k

m

depending on spontaneous magneto-

striction o

S

:

k

f

¼ k þ k

m

Ek þ o

S

=P

C

¼ kð1 þ o

S

GÞð5Þ

Nonlinear effects can indeed be expected under con-

ditions critical for the existence of magnetism where

the simple linear approximations will not be valid.

1.2 Theoretical Models

The theoretical treatment of pressure effects on mag-

netic properties of solids has been performed within

models of both localized and band magnetism (see

also Localized 4f and 5f Moments: Magnetism and

Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromag-

netism)).

The systems with localized magnetic moments are

very stable and almost insensitive to a compression

up to pressures that are capable of changing the elec-

tron occupation of the nonfilled inner atomic shells

(e.g., in thulium) or of delocalizing the magnetic

electrons (e.g., in cerium). Where the localized elec-

trons occupy sharp atomic energy levels, the atomic

spin moments S are well defined and their interaction

has been successfully described by the molecular field

model with the Heisenberg exchange interaction. In

the framework of this model, the Curie or Ne

´

el tem-

peratures T

C

, T

N

, respectively, of many simple ferro-,

ferri-, or antiferro-spin arrangements in solids have

been explained as a function of the moment and the

exchange interaction integral J, where 7J7 ¼3kT

C,N

/

2zS(S þ1), k is the Boltzmann constant and z is the

coordination number, i.e., the number of nearest

neighbors (see also Magnetism in Solids: General

Introduction). Pressure-induced changes of T

C

or T

N

are mainly a result of the pressure effect on the ex-

change interaction integral J. A simple relation can

be derived for this class of magnetic solids:

dlnJ=dlnV ¼ dlnT

C;N

=dlnV ¼ G ð6Þ

Nonintegral values of the atomic moments char-

acterize a magnetic state in metallic systems with

itinerant electrons. These partially delocalized elec-

trons participate on magnetic as well as on trans-

port—electric and thermal—properties of metals.

The effective electron–electron interaction J

f

and

the density of states on the Fermi level N(E

F

) play a

dominant role in the magnetism of itinerant elec-

trons. Both, J

f

and N(E

F

), are very sensitive to inter-

atomic distances. In general, a decrease in distances

between atoms in solids leads to an increase of both

the electron interactions and the width W of the

electron energy band. However, the effects of an in-

crease in J

f

and a decrease in N(E

F

)B1/W under

pressure can compensate each other in the Stoner

factor S

f

¼[1J

f

N(E

F

)]

1

; this factor is crucial for the

appearance of a magnetic state. Pressure derivatives

of both J

f

and N(E

F

) are strongly affected by many

factors: by the crystal lattice symmetry and the co-

ordination number or by the short-range order of

atoms (namely in the case of amorphous metals and

disordered alloys). In this respect, a variety of pres-

sure effects on the itinerant electron magnets may be

expected.

The models of band (itinerant electron) magnetism

enable pressure-induced changes of T

C

to be derived

698

Magnetic Sys tems: External Pressure-induced Phenomena

in a form suitable for further characterization of the

itinerant electron magnets. When T

C

is basically de-

termined by the Stoner relation, then

T

2

C

¼ T

2

F

½J

f

NðE

F

Þ1ð7Þ

where T

F

is the degeneracy temperature (usually

T

F

bT

C

) which depends on a fine structure of the

single particle density of states N(E) curve. Taking

into account effects of electron correlation, the effec-

tive electron interaction J

f

in transition metals with

a narrow energy d-band can be expressed by the

relation

J

f

¼ U=ð1 U=gWÞð8Þ

where U is the intra-atomic Coulomb energy of

d-electrons and g is a constant (Kanamori 1963).

Using the relations dlnW/dlnV ¼l and dlnJ

f

/

dlnV ¼l(J

f

/gW) ¼lR, the volume (or pressure)

derivative of Eqn. (7) raises the possibility of two

limiting cases of pressure dependence of T

C

in the

transition-metal ferromagnets (Wohlfarth 1981). In

the ‘‘strong itinerant ferromagnets’’ the effective elec-

tron interaction J

f

is comparable with the band width,

J

f

-gW, R-1, and T

C

increases with pressure. The

parameter dT

C

/dp is proportional to

dT

C

=dpBlkT

C

and GB l ð9Þ

The linear relation between dT

C

/dp and T

C

has

also been derived on the basis of detailed theoretical

calculations for crystalline NiCu alloys (Lang and

Ehrenreich 1968). In the ‘‘very weak itinerant ferro-

magnets’’ with J

f

5gW, R goes to zero and the pro-

nounced decrease of T

C

with pressure is described by

the well known Wohlfarth relation

dT

C

=dpB A

w

=T

C

and GB þ lS

f

ð10Þ

where A

w

is the Wohlfarth constant proportional

to þlkT

2

F

.

Calculations of the s–d interaction in transition

metals are able to describe the volume dependence of

the d-band width as WBR

5

which leads to l ¼5/3

(Heine 1967). The pressure (volume) dependence of

the band width W given by the parameter l controls

all the pressure-induced changes of the magnetic

characteristics of the transition metal ferromagnets in

the theoretical concept, where only single-particle ex-

citations have been taken into consideration.

Since the late 1980s the band calculations based on

the local spin density approximation (LSDA) (see

Density Functional Theory: Magnetism) have revealed

the instabilities of the transition-metal moments in

the volume instability ranges (Moruzzi and Marcus

1988). The theoretically predicted existence of two

ferromagnetic states, very close in energy, for iron in

the f.c.c. crystal structure, and the verification of the

Fe-moment stability in the more open b.c.c. crystal

structure, explains the anomalous magnetovolume

effects in Invar alloys (f.c.c.) as well as the almost

total insensitivity of the b.c.c.-Fe to external pres-

sures (see Invar Materials: Phenomena and references

therein).

1.3 High-pressure Techniques

Hydrostatic pressure enables the variation of inter-

atomic distances in compressed matter to an extent

similar to that achieved in the more widely used

chemical substitution, but it retains the composition,

purity, and shape of the sample. The pressure-in-

duced volume and energy changes are dependent on

the compressibility of a particular sample. Hence, the

high pressures comparable in magnitude with the

bulk modulus should be applied to obtain a sufficient

effect. Routinely, volume changes of up to B1–5%

per 1 GPa can be produced by hydrostatic pressure.

(The pressure unit Pa ¼Nm

2

is too small for this

purpose, so the unit GPa ¼10

9

Pa (B10000 atm) will

be used in this article.)

An example of the hydrostatic high pressure cell

used for measurements of magnetization is presented

in Fig. 1. The cell is filled by a liquid pressure medium

(mixture of oils, Fluorinert) which transmits pressure

on to a sample (fixed on the plug) without shear

stresses even during cooling of the cell down to liquid

helium temperature. The pressure inside the cell can

be increased easily up to 1.5GPa by a piston pushed

inside by a clamping bolt. The miniature pressure cell

is made from nonmagnetic CuBe bronze and can be

used inside a standard SQUID magnetometer. The

applied pressure can be measured inside the cell using

the known pressure-induced shift of the critical tem-

perature of the transition to the superconducting

state of lead (Garfinkel and Mapother 1961).

Hydrostatic CuBe cells of larger dimensions (with

an inner diameter of up to 12 mm) are widely used for

measurements of magnetoresistance, magnetostrict-

ion, or magneto-optical properties of solids under

Figure 1

High pressure CuBe microcell for magnetic studies in a

SQUID magnetometer, with inner diameter 2.5mm: 1,

9—upper and lower pressure clamping bolts; 2—plug;

3—sealing; 4—sample; 5—pressure cell; 6—Pb pressure

sensor; 7—piston; 8—piston backup.

699

Magnetic Sys tems: External Pressure-induced Phenomena