Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

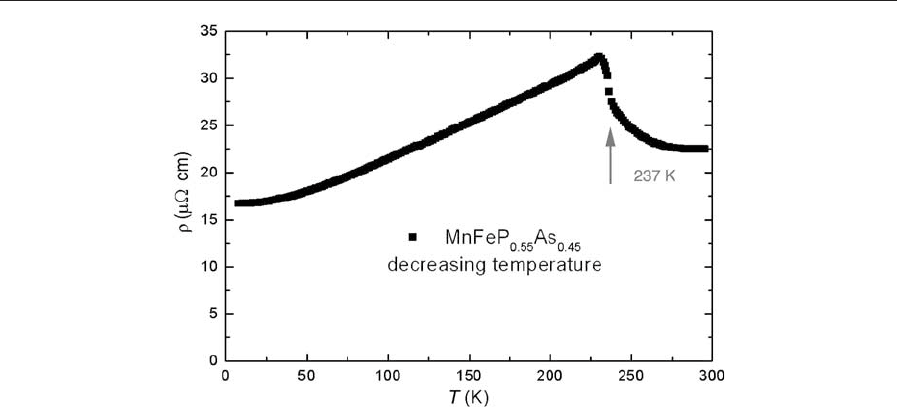

resistance of MnFeP

0.55

As

0.45

, measured during cool-

ing of the sample, is presented in Fig. 4. It can be seen

that there is an anomaly in the temperature depend-

ence of the electrical resistance at T

cr

¼231 K. Below

T

cr

, the electrical resistance increases with increasing

temperature and has metallic character but, above

T

cr

, it decreases dramatically in a narrow temperature

range and then recovers the metal-like dependence on

temperature. The total contribution from both the

electron–phonon scattering and the electron–magnon

scattering in the paramagnetic (PM) phase is smaller

than in the ferromagnetic (FM) phase which is con-

trary to normal ferromagnetic metallic materials. It is

interesting to note that the transition at T

cr

is ac-

companied by a change in the c/a ratio (Beckmann

and Lundgren 1991), which may lead to a change in

the Fermi-surface topology and may affect the elec-

tron–phonon scattering. Preliminary band-structure

calculations indicate a strong shift of the Fermi level

associated with the phase-transition (A. V. Antropov

personal communication 2002).

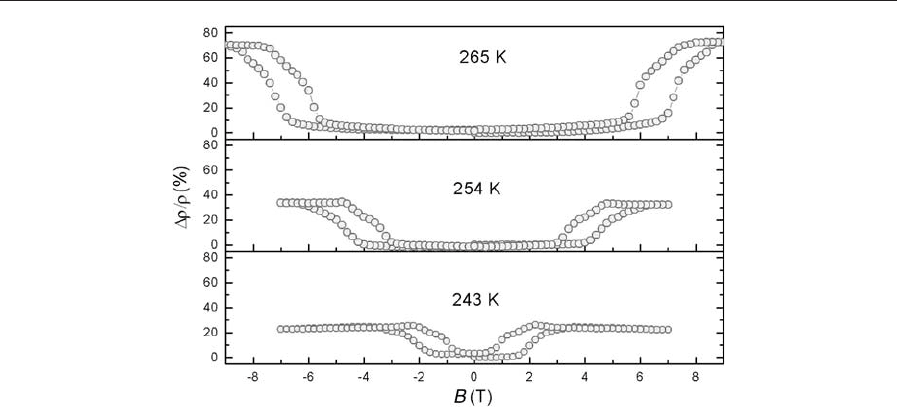

The isothermal magnetic-field-dependent hysteresis

loops of the magnetoresistance, defined as Dr/

r

0

¼(R(B,T)R(0,T))/R(0,T), in the temperature in-

terval from 243 K to 265 K are shown in Fig. 5. The

isothermal increase of the magnetic field leads to an

increase of the electrical resistance of MnFeP

0.55

As

0.45

beginning at a critical field B

cr1

and ending at

B

cr2

. Hence, between 243 K and 265 K in zero-field

the sample is PM but application of a magnetic field

exceeding B

cr1

brings it into the FM state. The field-

induced PM–FM transition ends at B

cr2

. During

the reduction of the magnetic field, the reversible

FM–PM transition begins at B

cr3

and ends at B

cr4

.

The behavior of the electrical resistance in a magnetic

field reflects the presence of magnetic-field hysteresis

for the complete PM–FM transition, which indicates

that also the field-induced transition is first-order.

Thus, the temperature and field dependence of the

electrical resistance of MnFeP

0.55

As

0.45

indicate that

a PM–FM phase transition can be induced both

by temperature and by magnetic field. The former

type of transition takes place from a high-resistance

ferromagnetic state at low temperature to a low-

resistance paramagnetic state at high temperature.

The latter type of transition leads to a positive mag-

netoresistance peak above T

c

. The critical-magnetic-

field diagram based on the electrical-resistance data

shows that the FM–PM transition has a hysteresis

of B1T.

In summary, we have observed a surprisingly large

magnetocaloric effect in the compound MnFe-

P

0.45

As

0.55

, which is comparable with that of the

giant-MCE material Gd

5

Ge

2

Si

2

. The large MCE

observed in MnFeP

1x

As

x

compounds originates

from a field-induced first-order magnetic phase tran-

sition. The magnetization is reversible in temperature

and in alternating magnetic field. The refrigerant ca-

pacity (Gschneidner and Pecharsky 1999) of the com-

pound MnFeP

0.45

As

0.55

, calculated for a temperature

span of 50 K, is larger than that of the well-known

magnetocaloric material Gd and the ordering tem-

perature of MnFeP

1x

As

x

compounds is tunable over

a wide temperature interval (200–350 K). The excel-

lent magnetocaloric features of the compound

MnFeP

0.45

As

0.55

, in addition to the very low mate-

rial costs, make it an attractive candidate material for

a commercial magnetic refrigerator.

Figure 4

Temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity of MnFeP

0.55

As

0.45

, measured with decreasing temperature.

680

Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Temperature

See also: Demagnetization: Nuclear and Adiabatic;

Magnetic Systems: Specific Heat; Magnetocaloric

Effect: From Theory to Practice

Bibliography

Annaorazov M P, Asatryan K A, Myalikgulyev G, Nikitin S A,

Tishin A M, Tyurin A L 1992 Alloys of the Fe–Rh system as

a new class of working material for magnetic refrigerators.

Cryogenics 32, 866–72

Annaorazov M P, U

¨

nal M, Nikitin S A, Tyurin A L, Asatryan

K A 2002 Magnetocaloric heat-pump cycles based on the

AF–F transition in Fe–Rh alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.

(in press online available August 21, 2002)

Bacmann M, Soubeyroux J L, Barrett R, Fruchart D, Zach R,

Niziol S, Fruchart R 1994 Magnetoelastic transition and

antiferro–ferromagnetic ordering in the system MnFeP

1y

As

y

. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 134, 59–67

Beckmann O, Lundgren L 1991 Compounds of transition el-

ements with nonmetals. In: Handbook of Magnetic Materials,

Vol. 6, North-Holland, Amsterdam

Choe W, Pecharsky V K, Pecharsky A O, Gschneidner K A Jr.,

Young V G, Miller G J 2000 Making and breaking covalent

bonds across the magnetic transition in the giant magneto-

caloric material Gd

5

Si

2

Ge

2

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4617–20

Gschneidner K A Jr., Pecharsky V K 1999 Magnetic refriger-

ation materials (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 85, 5365–8

Gschneidner K A Jr., Pecharsky V K, Pecharsky A O, Zimm O

A 1999 Recent developments in magnetic refrigeration.

Mater. Sci. Forum 315–317, 69–76

Hashimoto T, Numazawa T, Shino M, Okada T 1981 Cryo-

genics 21, 647

Hu F X, Shen B G, Sun J R 2000 Magnetic entropy change in

Ni

51.5

Mn

22.7

Ga

25.8

alloy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3460–2

Hu F X, Shen B G, Sun J R, Wu G H 2001a Large magnetic

entropy change in a Heusler alloy Ni

52.6

Mn

23.1

Ga

24.3

single

crystal. Phys. Rev. B 64, 132412

Hu F X, Shen B G, Sun J R, Cheng Z H 2001b Large magnetic

entropy change in La(Fe,Co)

11.83

Al

1.17

. Phys. Rev. B 64,

012409

Hueso L E, Sande P, Miguens D R, Rivas J, Rivadulla F,

Lopez-Quintela M A 2002 Tuning of the magnetocaloric

effect in La

0.67

Ca

0.33

MnO

3d

nanoparticles synthesized by

sol-gel techniques. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 9943–7

Krokozinsky H J, Santandrea C, Gmelin E, Barner K 1982

Specific heat anomaly connected with a high-spin–low-spin

transition in metallic MnAs

1x

P

x

crystals. Phys. Stat. Sol.

(b) 113, 185–95

Morellon L, Blasco J, Algarabel P A, Ibarra M R 2000 Nature

of the first-order antiferromagnetic–ferromagnetic transition

in the Ge-rich magnetocaloric compounds Gd

5

(Si

x

Ge

1–x

)

4

.

Phys. Rev. B 62, 1022–6

Pecharsky V K, Gschneidner K A Jr. 1997 Giant magneto-

caloric effect in Gd

5

(Si

2

Ge

2

). Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4494–7

Pecharsky V K, Gschneider K A Jr., Pecharsky A O, Tishin A

M 2001 Thermodynamics of the magnetocaloric effect. Phys.

Rev. B 64, art. no. 144406

Pytlik L, Zieba A 1985 Magnetic phase diagram of MnAs.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 51, 199–210

Tegus O, Bru

¨

ck E, Buschow K H J, de Boer F R 2002a Tran-

sition-metal-based magnetic refrigerants for room-tempera-

ture applications. Nature 415, 150–2

Tegus O, Duong N P, Dagula W, Zhang L, Bru

¨

ck E, Buschow

K H J, de Boer F R 2002b Magnetocaloric effect in

GdRu

2

Ge

2

. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 8528–30

Tishin A M 1999 Magnetocaloric effect in the vicinity of phase

transitions. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic

Materials, Vol. 12, pp. 395–524

Zach R, Guillot M, Fruchart R 1990 The influence of high

magnetic fields on the first order magneto-elastic transition in

MnFe(P

1y

As

y

) systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 89, 221–8

Zhang X X, Tejada J, Xin Y, Sun G F, Wong K W,

Bohigas X 1996 Magnetocaloric effect in La

0.67

Ca

0.33

MnO

d

and La

0.60

Y

0.07

Ca

0.33

MnO

d

bulk materials. Appl. Phys. Lett.

69, 3596–8

Figure 5

Magnetoresistance of MnFeP

0.55

As

0.45

, measured near the critical temperature.

681

Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Temperature

Zimm C, Jastrab A, Sternberg A, Pecharsky V, Geschneidner

K Jr. 1998 Description and performance of a near-room

temperature magnetic refrigerator. Adv. Cryog. Eng. 43,

1759–66

E. Bru

¨

ck

University van Amsterdam, Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Magnetic Steels

Iron is a major constituent in many ferromagnetic

materials. Iron is abundant, cheap, and it has the

largest elemental magnetic dipole moment, of 2.2

Bohr magnetons (m

B

). Two defining intrinsic mag-

netic properties of a ferromagnet are (i) the saturation

magnetic induction associated with the former, and

(ii) the Curie temperature. Magnetic induction is the

magnetic response to an applied magnetic field; mag-

netic exchange coupling persists to the Curie temper-

ature. With few exceptions the average magnetic

dipole moment and Curie temperature, T

C

, of ferrous

alloys are reduced as compared to elemental iron

(Bozorth 1951) and most alloying additions are made

to alter properties other than exchange and dipole

moment. The distinction between magnetically soft

and hard materials is understood in terms of the

magnetic hysteresis curve, B(H), as discussed in

Magnetic Hysteresis. Magnetic Hysteresis represents

the energy consumed in cycling a soft magnetic mate-

rial between a field H and H and back (for a

material with a square hysteresis loop this loss is

equal to the saturation induction multiplied by the

coercive field, H

C

) as well as the stored energy in a

hard or permanent magnetic material.

1. Magnetically Soft Materials

Technical properties of interest for soft magnets in-

clude: (i) high permeability (m ¼B/H); (ii) low hyster-

esis loss, and (iii) low eddy current and anomalous

losses. For soft magnets a small magnetic anisotropy

(the barrier to switching the magnetization) is desired

to minimize the hysteretic losses and maximize the

permeability. A desire for small magnetocrystalline

anisotropy guides the choice of cubic crystalline

phases of iron, cobalt, nickel or alloys (FeCo, FeNi,

etc., with small values of K

1

) (Jiles 1991). In crystal-

line alloys, such as Fe–Ni, permalloy, or Hiperco,

FeCo, alloy chemistry is varied so that the first-order

magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy density, K

1

,is

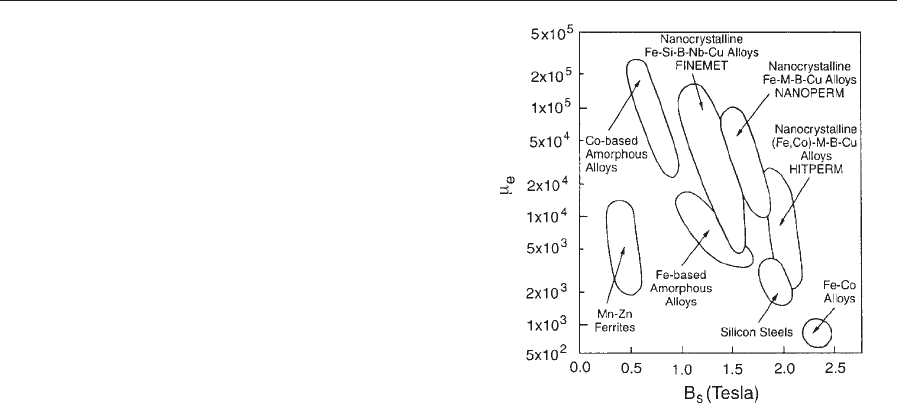

minimized. Figures of merit for magnetically soft

materials include the magnetic permeability and in-

duction, as illustrated for premier soft materials in

Fig. 1. Silicon steels, amorphous and nanocrystalline

soft magnetic materials are discussed in Nanocrystal-

line Materials: Magnetism. Among other soft mag-

netic steels FeCo is prominent for its high induction

and Curie temperature and FeNi (permalloy) for its

large permeability.

FeCo soft magnetic steels (Chen 1986) have

evolved under the tradenames Permendur, Super-

mendur and Hiperco (Hiperco50 is a tradename of

CarpenterTechnology). Fe–Co alloys exhibit the

largest magnetic induction of any material, at com-

position near the peak in the well-known Slater–

Pauling curve. Alloys near the equiatomic composi-

tion exhibit large permeabilities (Pfeifer and Radeloff

1980, Rajkovic and Buckley 1981, Boll 1994). This

magnetic softness is rooted in a zero crossing of the

first-order magnetic anisotropy constant, K

1

, near

this composition. Vanadium additions are made for

metallurgical reasons and to increase alloy resistivity

and decrease eddy current losses. The Fe–Co alloys

undergo an order–disorder transformation at a max-

imum temperature of 725 1C at the composition

Fe

50

Co

50

, with a change in structure from the disor-

dered b.c.c.(A1) to the ordered CsCl(B2)-type struc-

ture. This ordering is important to the mechanical

properties of this alloy and influences intrinsic mag-

netic properties slightly.

Permalloy refers to FeNi soft magnetic alloys of

which three compositions are of technical interest

(O’Handley 2000). These are a 78% nickel permalloy

called supermalloy (Mumetal, Hi-mu 80), a 65%

nickel permalloy and a 50% nickel permalloy (Del-

tamax). These are based on f.c.c. Fe–Ni with Curie

Figure 1

(a) Relationship between permeability, m

e

(at 1 kHz) and

saturation polarization for soft magnetic materials

(McHenry et al. 1999, reproduced by permission of from

Progress in Materials Science, 1999, 44, 291).

682

Magnetic St eels

temperatures in excess of 400 1C. Owing to Fe–Ni

pair ordering, these materials are quite responsive to

field annealing, which is used to shape their hysteresis

loops and to increase permeability.

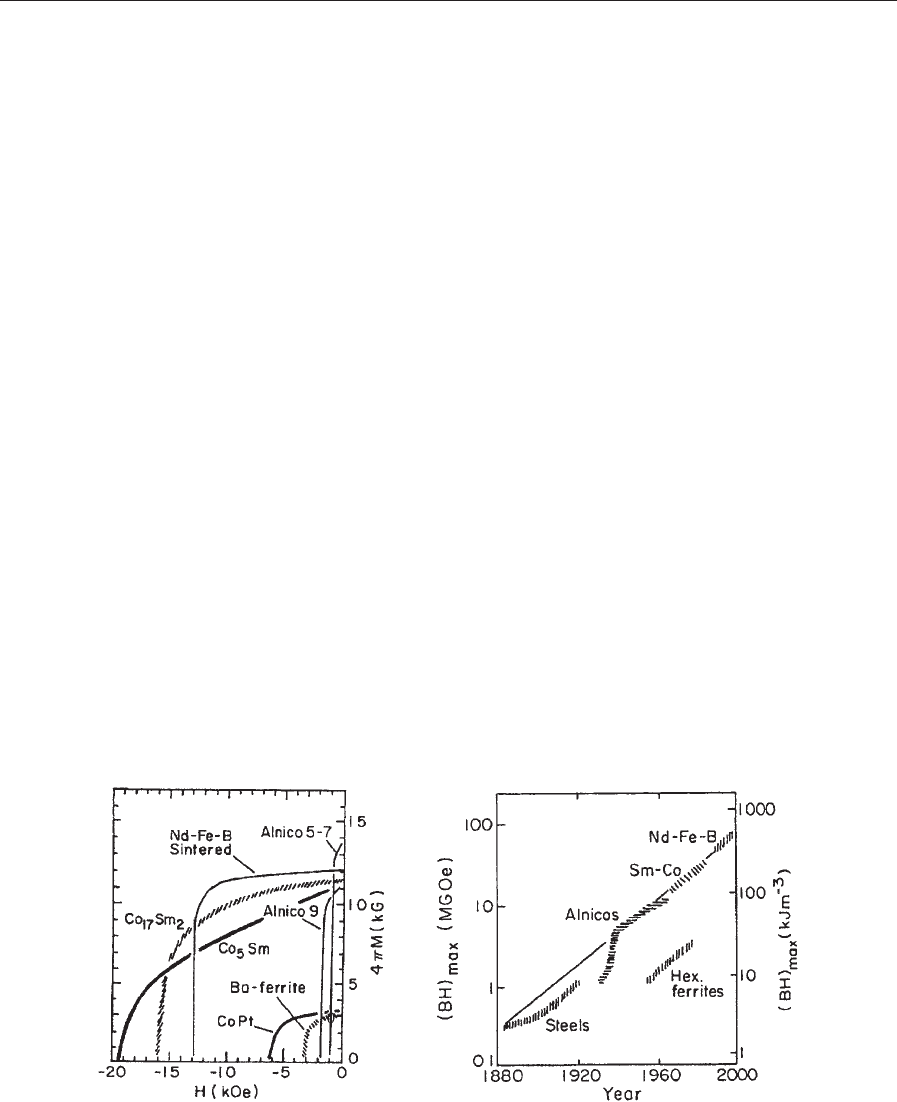

2. Magnetically Hard Materials

Magnetically hard materials or permanent magnets

are ubiquitous. Among the many applications of

permanent magnets are small motors, loudspeakers,

communications, electronic tubes and mechanical

work devices. For a permanent magnet material,

large amounts of magnetic hysteresis are desired, with

figures of merit including the coercive force, the rem-

nant magnetization and the energy product, (BH)

max

.

The remnant magnetization, M

r

, or induction, B

r

,

represents the largest amount of magnetization pos-

sible in the absence of a field. The coercive field, H

c

,

represents the amount of reverse field required to re-

duce the magnetization to zero after being saturated

in the forward direction. For a material with a square

hysteresis loop, the energy product, (BH)

max

, is de-

fined at the maximum demagnetizing field, in the de-

magnetizing quadrant of a hysteresis loop (Fig. 2(a))

(O’Handley 2000). The energy product is the most

commonly used figure of merit for permanent magnet

materials. (See Hard Magnetic Materials, Basic

Principles of .)

There are a large number of iron-based and iron

oxide-based permanent magnet alloys. Magnetite,

Fe

2

O

3

, is named after the district in which it was first

discovered, Magnesia in ancient Greece. Lodestone

(magnetite) was mentioned in the writing of Greek

philosophers and used in compasses guiding ancient

mariners (Parker 1990). Technology for developing

steel wires for compass needles (Coey 1996) was de-

veloped during the Sung period (960–1279) in China.

Prior to 1917, permanent magnets made of plain car-

bon steels were weak and unstable with respect to

demagnetization by self-fields. This led to geometric

constraints (i.e., the horseshoe magnet) to exploiting

these materials as permanent magnets. Steel magnets

used prior to 1917 included plain carbon, tungsten

and chrome steels (Cullity 1972).

A figure of merit for permanent magnet materials

is their energy product defined above. Modern per-

manent magnets have progressed in several notable

steps. In 1917 cobalt steels were discovered in Japan

(see Honda and Saito 1920). This evolution contin-

ued with the later development of AlNiCo magnets.

AlNiCo is a permanent magnet derived from the

intermetallic Fe

2

NiAl Heusler alloy. AlNiCo magnets

(see McCurrie 1994) derive their magnetic hardness

from the shape of iron-rich particles which form on

spinodal decomposition of the Heusler alloy into

a-Fe and a

0

-NiAl phases. AlNiCo magnets are cur-

rently still a significant fraction of the permanent

magnet market. Phases in the FePt and CoPt system

were studied as early as 1936 by Jellinghaus, who

observed them to have the highest energy products of

any alloys known at that time (see Bozorth 1993).

Important among these phases is the equiatomic

FePt and CoPt, possessing the tetragonal L1

0

crystal

structure. The specialty magnet, MnAlC, also has

a tetragonal L1

0

crystal structure. (See Magnetic

Materials: Hard ).

Powdered iron and cobalt oxide magnets discov-

ered in Japan by Kato and Takei (1933), and com-

mercialized under the name Vectolite, were the

forerunners of modern ferrite magnets. Synthetic

hard hexagonal ferrites were developed by Philips

Figure 2

(a) Demagnetization curves for several premier hard magnetic materials and (b) historical progression of the magnetic

energy product figure of merit for hard magnets (O’Handley 2000, reproduced by permission of Wiley from ‘Modern

Magnetic Materials, Principles and Applications,’ 2000).

683

Magnetic Steels

laboratories in the Netherlands during the 1950s.

Went et al. (1952) first reported on isotropic barium

hexaferrite magnets and Stuijts et al. (1954) reported

on anisotropic strontium hexaferrites. While ferrite

magnets have never held record energy products, be-

cause of their relatively inexpensive components and

ease of fabrication, they constitute a large fraction of

the permanent magnet market. (See Permanent

Magnets: Bonded.)

A major development in the evolution of high en-

ergy permanent magnet materials has been the dis-

covery of rare earth permanent magnet materials,

REPMs. These materials are notable for their large

magnetocrystalline anisotropies that are at the root

of their large coercivities. Appropriate choice of the

rare earth to transition metal ratios in REPMs results

in large remnant and saturation magnetizations. The

hexagonal, P6/mmm, structure of CaCu

5

is the pro-

totype for the important permanent magnet material

SmCo

5

. SmCo

5

was first synthesized by Nassau,

Cherri, and Wallace (1960), and Strnat and Hoffer

(1966) are credited with first calling attention to its

potential use as a permanent magnet material. It still

has the highest uniaxial magnetic anisotropy

(K

u

¼10

7

Jm

3

) of any known material. REPMs

have evolved over the years and presently two fam-

ilies of permanent magnets have found commercial

importance. The first of these are the Sm

2

Co

17

(2:17)

and the second the Fe

14

Nd

2

B (2:14:1)-based perma-

nent magnets. (See Rare Earth Magnets: Materials.)

The 2:17 materials have favorable intrinsic prop-

erties: remanent induction B

r

¼1.2 T (25 1C), intrinsic

coercivity,

i

H

c

¼1.2 T (25 1C) and T

c

¼920 1C (e.g., in

comparison to 750 1C for SmCo

5

) . Higher 3d metal

content leads to higher T

c

values. The 2:17 magnets

currently in commercial production have a composi-

tion Sm(CoFeCuM)

7.5

. Iron additions are made to

increase the remanent induction (Huang et al. 1994);

copper and M (zirconium, hafnium, or titanium) ad-

ditions are made to influence precipitation hardening.

Typical 2:17 Sm–Co magnets with large H

c

are ob-

tained through a low temperature heat treatment

used to develop a cellular microstructure. Small cells

of the 2:17 matrix phase are separated (and usually

completely surrounded) by a thin layer of the harder

1:5 phase. The cell interior contains both a heavily

twinned rhombohedral modification of the 2:17 phase

and coherent platelets of the so-called z-phase (Fidler

and Skalicky 1982), which is rich in iron and M

and has the hexagonal 2:17 structure. Typical micro-

structures have a 50–100 nm cellular structure, with

5–20 nm thick cell walls.

Iron-based rare-earth intermetallic compounds

were investigated by Das and Koon (1981), Croat

(1981), and Hadjipaynias et al. (1983). Commercial

Fe

14

Nd

2

B permanent magnets were first synthesized

in 1984 by sintering by a group at Sumitoma Metals

(Sagawa et al. 1984) and by rapid solidification

processing by a group at General Motors (Croat et al.

1984). Uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy

(K

u

¼10

7

Jm

3

) in these materials results from their

tetragonal crystal structure. These materials are

based on the cheaper more abundant iron transition

metal. They have the largest room temperature en-

ergy products of any materials synthesized to date

but their lower Curie temperatures as compared with

Co-based magnets makes them unsuitable for high

temperature applications.

See also: Alnicos and Hexaferrites; Ferrite Magnets:

Improved Performance; Magnets: Sintered

Bibliography

Boll R 1994 Soft magnetic metals and alloys. In: Buschow K H

J (ed.) Materials Science and Technology, A Comprehensive

Treatment. VCH, Weinheim, Vol. 3B, Chap. 14, pp. 399–451

Bozorth R M 1951 Ferromagnetism. Van Nostrand, New York

Bozorth R M 1993 Ferromagnetism. IEEE Press, New York

Chen C W 1986 Magnetism and Metallurgy of Soft Magnetic

Materials. Dover Publications, New York

Coey J M D 1996 Rare Earth Iron Permanent Magnets. Claren-

don, Oxford

Croat J J 1981 Observation of large room-temperature

coercivity in melt-spun Nd

0.4

Fe

0.6

. Appl. Phys. Lett. 39,

357–8

Croat J, Herbst J F, Lee R W, Pinkerton F E 1984 Pr-Fe and

Nd-Fe-based materials–a new class of high performance per-

manent magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 2078

Cullity B D 1972 Introduction to Magnetic Materials. Addison-

Wesley, Reading, MA

Das B N, Koon N C 1983 Correlation between microstructure

and coercivity of amorphous (Fe

0.82

B

0.18

)

0.90

Tb

0.05

Ca

0.05

alloy ribbons. Metall. Trans. 14A, 953–61

Fidler J, Skalicky P 1982 Microstructure of precipitation hard-

ened cobalt rare earth permanent magnets. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 27, 127–34

Hadjipaynias G, Hazelton R, Lawless K R 1983 New iron–rare

earth based permanent magnet materials. Appl. Phys. Lett.

43, 797–9

Honda K, Saito S 1920 On K-S magnet steel. Sci. Rep. Tohoku

Imp. Univ. 9, 417–22

Huang M Q, Zheng Y, Wallace W E 1994 SmCo (2:17-type)

magnets with high contents of Fe and light rare earths.

J. Appl. Phys. 75, 6280–2

Jellinghaus W 1936 New alloys with high coercive force.

Z. Tech. Phys. 17, 33–6

Jiles D 1991 Introduction to Magnetism and Magnetic Materials.

Chapman and Hall, London

Kato Y, Takei T 1933 Permanent oxide magnet and its char-

acteristics. J. Inst. Elect. Engrs. (Jpn.) 53, 408–12

McCurrie R A 1994 Ferromagnetic Materials: Structure and

Properties. Academic Press, London

McHenry M E, Willard M A, Laughlin D E 1999 Amorphous

and nanocrystalline materials for applications as soft mag-

nets. Prog. Mat. Sci. 44, 291–441

Nassau K, Cherri L V, Wallace W E 1960 Intermetallic com-

pounds between lanthonons and transition metals of the first

long period. 1. Preparation, existence and structural studies.

J. Phys. Chem. Sol. 16, 123–30

O’Handley R C 2000 Modern Magnetic Materials, Principles

and Applications. Wiley, New York

684

Magnetic St eels

Parker R J 1990 Advances in Permanent Magnetism. Wiley, New

York

Pfeifer F, Radeloff C 1980 J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 19, 190

Rajkovic M, Buckley R A 1981 Metal Sci. 21

Sagawa M, Fujimura S, Togawa N, Yamamoto H, Matsuura Y

1984 New material for permant magnets on a base of Nd and

Fe. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 2083–7

Strnat J, Hoffer G 1966 In: USAF Materials Lab. Report

AFML TR-65, p. 446

Stuijts A, Ratheneau G, Weber G 1954 Philips Tech. Rev. 16,

141

Went J, Ratheneau G, Gorter E, Van Ooosterhaut G 1952

Philips Tech. Rev. 13, 194

M. E. McHenry

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

Pennsylvania, USA

Magnetic Systems: De Haas–van Alphen

Studies of Fermi Surface

Strongly correlated electron systems such as high-T

c

cuprates, cerium, and uranium compounds have at-

tracted strong interest with respect to the non-BCS

superconducting property. The f-electron systems of

the rare-earth and uranium compounds have been

studied in the context of Kondo lattice, heavy fermi-

on, Kondo insulator, anisotropic superconductivity,

RKKY interaction, and quadrupolar ordering. These

are based on the hybridization effect between the

conduction electrons with a wide energy band and the

almost localized f-electrons. The Kondo effect, espe-

cially, is a basic phenomenon in the cerium and ura-

nium compounds, consequently yielding a large

electronic specific heat coefficient g of the conduc-

tion electron with an extremely large effective mass

(O

%

nuki et al. 1991, O

%

nuki and Komatsubara 1987). It

is a challenging study to detect the heavy conduction

electron via the standard de Haas–van Alphen

(dHvA) experiment.

1. De Haas–van Alphen Effect

The dHvA effect is caused when the Landau levels

cross the Fermi energy as the magnetic field is in-

creased. It provides a powerful tool for determining

the topology of the Fermi surface, the cyclotron ef-

fective mass m

c

and the scattering lifetime t of the

conduction electron. This method of dHvA measure-

ment is illustrated in this article with the strongly

correlated electron systems of the transition, rare-

earth and uranium compounds (O

%

nuki et al. 1991,

O

%

nuki and Hasegawa 1995).

The dHvA voltage V

osc

is obtained in so-called 2o

detection of the field modulation method:

V

osc

¼ Asin

2pF

H

þ f

ð1Þ

ApJ

2

ðxÞTH

1=2

@

2

S

@k

2

H

1=2

expðam

c

T

D

=HÞ

sinhðam

c

T=HÞ

cos

pgm

c

2m

0

ð2Þ

a ¼

2p

2

k

B

e_

ð3Þ

and

x ¼

2pFh

H

2

ð4Þ

where J

2

(x) is the Bessel function, which depends on

the dHvA frequency F, the modulation field h, and

the magnetic field strength H. The dHvA frequency F

( ¼(_/2pe)S

F

) is proportional to the extremal (max-

imum or minimum) cross-sectional area S

F

of the

Fermi surface, and T

D

( ¼_ /2pk

B

)t

1

is the Dingle

temperature, which is inversely proportional to t. The

quantity 7@

2

S/@k

H

2

7

1/2

is the inverse square root of

the curvature factor @

2

S/@k

H

2

. A rapid change of the

cross-sectional area along the field direction dimin-

ishes the dHvA amplitude for this extremal area. The

term cos(pgm*

c

/2m

0

) is called the spin factor. When

g ¼2 (free electron value) and m*

c

¼0.5 m

0

, this term

becomes zero for the fundamental oscillation, and the

dHvA oscillation vanishes for all values of the mag-

netic field.

This is called the zero spin-splitting situation, in

which the up and down spin contributions to the os-

cillation cancel out. The cyclotron mass is determined

from the temperature dependence of the dHvA am-

plitude A under a constant field, namely from the

slope of a plot of ln A[1exp(2am*

c

T/H)]/T vs T at

constant H and h, by using a method of successive

approximations. The Dingle temperature is also de-

termined from the field dependence of the dHvA am-

plitude at constant temperature, namely from the

slope of a plot of ln[AH

1/2

sinh(am*

c

T/H)/J

2

(x)] vs

H

1

at constant temperature.

Three typical compounds Sr

2

RuO

4

, CeRu

2

Si

2

, and

UPt

3

, with extremely large cyclotron masses, will be

discussed to demonstrate the use of dHvA effect

studies.

2. Cylindrical Fermi Surfaces in Sr

2

RuO

4

Sr

2

RuO

4

, with the same tetragonal crystal structure

as the high-T

c

superconductor La

2x

Sr

x

CuO

4

,isa

685

Magnetic Systems: De Haas-van Alphen Studies of Fermi Surface

possible candidate for a p-wave (odd parity) pairing

state (Ishida et al. 1997). The superconducting tran-

sition temperature T

c

is 1.5 K in Sr

2

RuO

4

, in contrast

to 40 K in La

2x

Sr

x

CuO

4

with a d-wave (even parity)

pairing state, where the quasi-two-dimensional net-

work of the CuO

2

plane is replaced by the RuO

2

one.

The electronic state is two-dimensional, reflecting

the crystal structure; this was clarified by the dHvA

measurement and the result of energy band structure

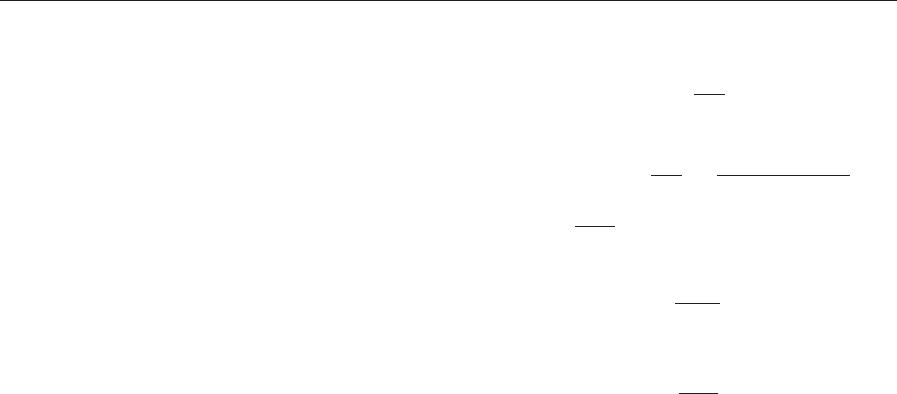

calculations (Yoshida et al. 1999). Figure 1 shows the

typical dHvA oscillation and its fast Fourier trans-

form (FFT) spectrum for the magnetic field along the

tetragonal [001] direction, or the c-axis. Three fun-

damental dHvA branches, named a, b(b

1

and b

2

), and

g, as well as higher harmonics of a, namely 2a,3a,4a,

and the combined harmonics (b

2

7a and g7a), are

presented in Fig. 1(b).

Figure 2 shows the angular dependence of the

dHvA frequency. The solid curves for the fundamen-

tal branches represent the 1/cosy-dependence, where

y is a tilt angle from [001] to [100]. The 1/cosy-

dependence means a cylindrical Fermi surface. For

example, branch b splits into two branches around

[001], denoted by b

1

and b

2

, which merge into one at

yE30 1. This angle corresponds to a so-called Yamaji

angle, where all orbits on the cylindrical but slightly

corrugated Fermi surface have the same cross-sec-

tional area. The theoretical Fermi surfaces for

branches a, b and g are shown in Fig. 3. They are

mainly due to hybridized orbitals of Ru(4 d) and

O(2p).

From the temperature dependence of the dHvA

amplitude A, namely the magnitude of the FFT

spectrum in Fig. 1(b), we can determine the cyclotron

effective mass m

c

for each Fermi surface. The cyclo-

tron mass is 3.3 m

0

for branch a, 6.9 m

0

for b, and 17

m

0

for g. It is noted that the corresponding band

masses are 1.0, 1.9, and 2.8 m

0

, respectively. The

largest cyclotron mass of branch g is six times larger

than the band mass. The corresponding electronic

specific heat coefficient is easily calculated, being 4.9,

10, and 25 mJK

2

mol

1

, respectively. The total

g-value is 40 mJK

2

mol

1

, which is in good agree-

ment with the measured g-value of 39.8 mJK

2

mol

1

(Yoshida et al. 1999).

3. Heavy Conduction Electrons in CeRu

2

Si

2

Based on the Kondo Effect

CeRu

2

Si

2

possesses tetragonal crystal structure, with

one molecule per primitive cell. Important properties

of this compound are described in Heavy-fermion Sys-

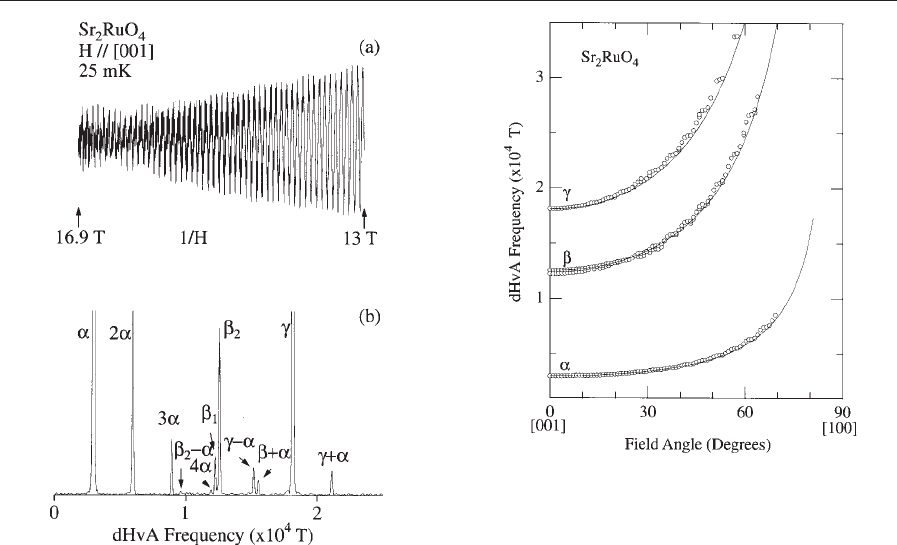

tems. Figure 4 shows the typical dHvA oscillation for

the field along the [100] direction and its FFT spec-

trum. Four dHvA branches named b, g, c*, and c,as

well as their harmonics, are presented in Fig. 4(b).

Figure 2

Angular dependence of the dHvA frequency in

Sr

2

RuO

4

. The solid lines indicate the 1/cosy-dependence.

Figure 1

(a) De Haas–van Alphen oscillation; (b) its FFT

spectrum in Sr

2

RuO

4

.

686

Magnetic Sys tems: De Haas-van Alphen Studies of Fermi Surface

Figure 5 shows the angular dependence of the

dHvA frequency (Takashita et al. 1996) and the result

of energy band calculations (Yamagami and Has-

egawa 1993). All dHvA branches are characterized as

follows:

*

branches c and c*: band-14 hole

*

branches k, e, and a: band-15 electron

*

branch g: band-13 hole

*

branch b: band-12 hole.

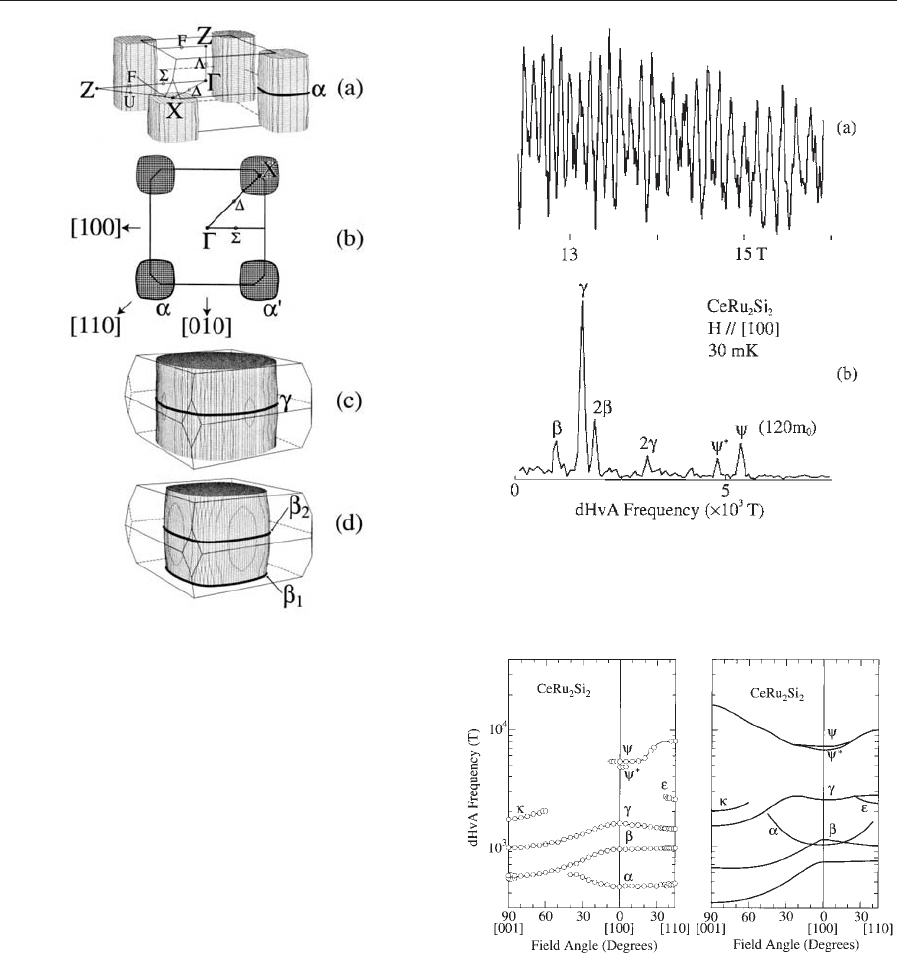

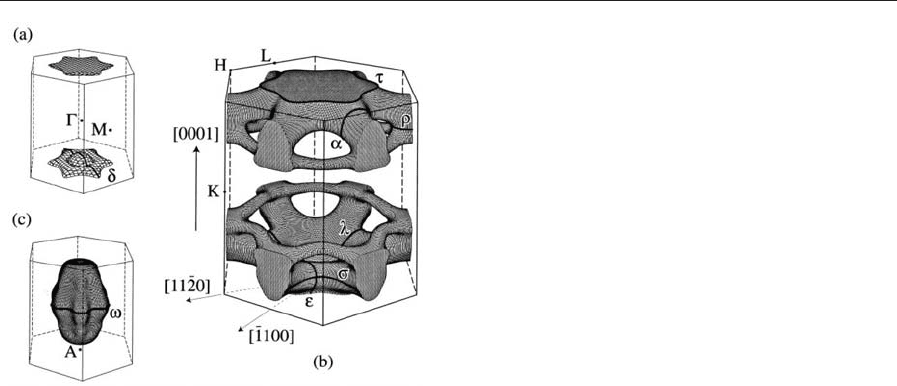

The theoretical Fermi surfaces are shown in Fig. 6.

These Fermi surfaces are calculated by a relativistic

augmented plane wave (APW) method with a local-

density approximation (LDA), under the assumption

that 4f-electrons are itinerant. The experimental re-

sult is in good agreement with the 4f-itinerant band

model, although the calculated Fermi surface has a

slightly larger volume than the experimental one.

On the other hand, the cyclotron effective mass,

which was determined from the temperature depend-

ence of the dHvA amplitude, is very different from

the band mass, because the many-body Kondo effect

is not included in the conventional band theory. The

cyclotron mass of the branch c is extremely large, 120

m

0

for the field along [100]. The corresponding band

mass is 1.93 m

0

. The experimental mass is about 60

times larger than the band mass. The dHvA branches

c and c* are not observed around [001]. This is be-

cause the metamagnetic transition occurs at about

8 T and the cyclotron effective mass is expected to

Figure 3

Fermi surfaces of (a) and (b) band-17 hole; (c) band-18

electron; (d) band-19 electron in Sr

2

RuO

4

.

Figure 4

(a) De Haas–van Alphen oscillation and (b) its FFT

spectrum in CeRu

2

Si

2

.

Figure 5

(a) Angular dependence of the detected dHvA frequency

and (b) the result of 4f-itinerant band calculations in

CeRu

2

Si

2

.

687

Magnetic Systems: De Haas-van Alphen Studies of Fermi Surface

become much larger than 120 m

0

. This transition is

confirmed to be not of the first order (Sakakibara

et al. 1995). The electronic state in fields above the

metamagnetic transition is still under study.

In conclusion, the 4f-electrons in CeRu

2

Si

2

are

confirmed by the dHvA study to become itinerant at

low temperatures. The conduction electrons, includ-

ing the 4f-electrons, form a so-called ‘‘large Fermi

surface.’’ This Fermi surface is very different from the

corresponding small Fermi surface of LaRu

2

Si

2

,in

which the 4f-levels are far above the Fermi energy and

do not contribute to the conduction electron states.

4. Itinerant 5f -electrons in UPt

3

UPt

3

, with hexagonal structure, is a prime candidate

for the unconventional pairing state to be realized (Tou

et al. 1998). Superconductivity in UPt

3

coexists with

antiferromagnetic ordering, with a Ne

´

el temperature

of about 5 K. This ordering is, however, not static but

dynamic. To understand the 5f-electron nature, it is

vitally important to clarify the Fermi surface property

(Kimura et al. 1998).

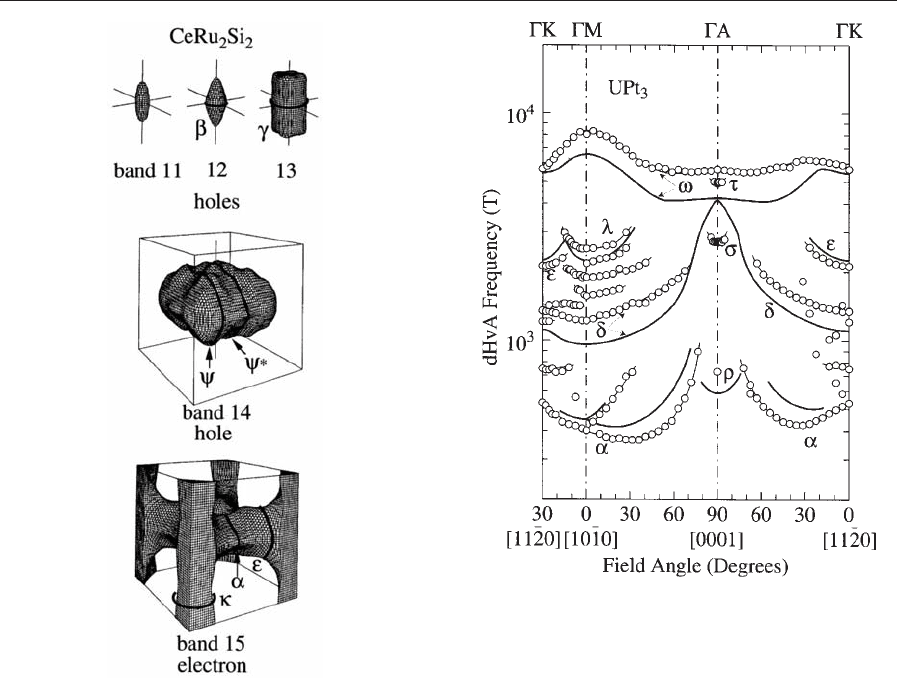

Figure 7 shows the angular dependence of the

dHvA frequency. The origin of the detected dHvA

branches will be identified on the basis of the 5f-itin-

erant band model. Figure 8 shows the theoretical

Fermi surfaces. The branches are as follows:

*

branch o: band-37 electron

*

branch t, s, r, l, e, and a: band-36 hole

*

branch d: band-35 hole.

The dHvA frequencies, shown by circles in Fig. 7,

are in good agreement with theoretical results (the

solid lines) of the 5f-itinerant band model. The branch

o possesses the largest cross-sectional area and cy-

clotron mass. The mass is determined as 80 m

0

in the

field range of 15 to 17.5 T for the field along [0001],

105 m

0

in the field range of 18.2 to 19.6 T for [101

%

0],

and 90 m

0

in the field range of 17 to 19.6 T for [112

%

0].

The corresponding band masses are 5.09, 6.84, and

5.79 m

0

. The cyclotron masses are about 15 times

larger than the corresponding band masses. It should

be noted that all bands contain an f-electron compo-

nent of about 70% and are flat in the dispersion.

Figure 6

Theoretical Fermi surfaces in CeRu

2

Si

2

(after

Yamagami and Hasegawa 1993).

Figure 7

Angular dependence of the dHvA frequency in UPt

3

.

Solid lines indicate the result of 5f-itinerant band

calculations.

688

Magnetic Sys tems: De Haas-van Alphen Studies of Fermi Surface

In theory, nearly spherical Fermi surfaces of a

band-37 electron centered at the K point in the Brill-

ouin zone, and band-38 and -39 electrons at the G

point are present, but they are not observed experi-

mentally. We suppose that they are not present. If

these electrons are not present, the main Fermi surface

named o has to become larger than that in Fig. 8(c).

In fact, the experimentally determined cross-section is

larger than the theoretical one, as shown in Fig. 7.

Thus it can be concluded that the 5f-electrons in

UPt

3

are of itinerant nature. Namely, the dHvA

results are well explained by the 5f -itinerant band

model, although a slight alteration is necessary. All

branches are heavy, with cyclotron masses of 15–105

m

0

, i.e., 10 to 20 times larger than the corresponding

band masses. The mass enhancement is caused by

magnetic fluctuations, where the freedom of charge

transfer of the 5f-electrons appears in the form of the

5f-itinerant band, but the freedom of spin fluctuation

of the same 5f-electrons reveals an unusual magnetic

ordering and enhances the effective mass as in the

many-body Kondo effect. These heavy conduction

electrons, or quasiparticles, condense into Cooper

pairs. To avoid a large overlap of the wave functions

of the paired particles, the heavy-fermion state would

rather choose an anisotropic channel, like a p-wave

spin triplet, to form Cooper pairs in UPt

3

.

5. Conclusion

We presented dHvA studies on the strongly corre-

lated electron systems of Sr

2

RuO

4

, CeRu

2

Si

2

, and

UPt

3

. A low temperature of 20 mK and a high mag-

netic field of 20 T can be obtained with a commercial

dilution refrigerator and a superconducting magnet,

respectively. These are necessary conditions to detect

a conduction electron with a large mass of 100 m

0

in

the dHvA experiment for CeRu

2

Si

2

and UPt

3

. More-

over, a high-quality sample is vitally important: the

band-37 electron with 100 m

0

in UPt

3

was not ob-

served for the sample of the residual resistivity ratio

(RRR ¼r

RT

/r

0

) of 300–400, but was observed for

RRR ¼600–700, where r

RT

and r

0

are the electrical

resistivity at room temperature and the residual

resistivity, respectively.

The topology of the detected Fermi surface is well

explained by energy band calculations based on the

density functional theory in LDA. The cyclotron

mass is, however, very different from the correspond-

ing band mass, because the many-body Kondo effect

is not included in the conventional band theory.

These Fermi surface properties should shed light on

the basic understanding of strongly correlated mag-

netic materials.

See also: Electron Systems: Strong Correlations;

Heavy-fermion Systems; Non-Fermi Liquid Be-

havior: Quantum Phase Transitions

Bibliography

Ishida K, Mukuda H, Kitaoka Y, Asayama K, Mao Z Q, Mori

Y, Maeno Y 1998 Spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr

2

RuO

4

identified by

17

O Knight shift. Nature 396, 658–60

Kimura N, Komatsubara T, Aoki D, O

%

nuki Y, Haga Y,

Yamamoto E, Aoki H, Harima H 1998 Observation of a

main Fermi surface in UPt

3

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 67, 2185–8

O

%

nuki Y, Goto T, Kasuya T 1991 Fermi surfaces in strongly

correlated electron systems. In: Buschow K H J (ed.) Mate-

rials Science and Technology. VCH, Weinheim, Germany,

Vol. 3A, pp. 545–626

O

%

nuki Y, Hasegawa A 1995 Fermi surfaces of intermetallic

compounds. In: Gschneidner Jr. K A, Eyring L (eds.) Hand-

book on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Elsevier,

Amsterdam, Vol. 20, pp. 1–103

O

%

nuki Y, Komatsubara T 1987 Heavy fermion state in CeCu

6

.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 63–4, 281–8

Sakakibara T, Tayama T, Matsuhira K, Mitamura H, Amitsuka

H, Maezawa K, O

%

nuki Y 1995 Absence of a first-order meta-

magnetic transition in CeRu

2

Si

2

. Phys. Rev. B 51, 12030–33

Takashita M, Settai R, O

%

nuki Y 1996 dHvA effect of meta-

magnetic transition in CeRu

2

Si

2

II—the state above the

metamagnetic transition. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 65, 515–24

Tou H, Kitaoka Y, Ishida K, Asayama K, Kimura N, O

%

nuki Y,

Yamamoto E, Haga Y, Maezawa K 1998 Nonunitary spin-

triplet superconductivity in UPt

3

: evidence from

195

Pt Knight

shift study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3129–32

Yamagami H, Hasegawa A 1993 A local-density band theory

for the Fermi surface of the heavy-electron compound

CeRu

2

Si

2

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 62, 592–603

Yoshida Y, Mukai A, Settai R, Miyake K, Inada Y, O

%

nuki Y,

Betsuyaku K, Harima H, Matsuda T D, Aoki Y, Sato H 1999

Fermi surface properties in Sr

2

RuO

4

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 68,

3041–53

Y. O

%

nuki

Osaka University, Japan

Figure 8

Theoretical Fermi surfaces in UPt

3

: (a) band-35 (hole),

(b) band-36 (hole), (c) band-37 (electron).

689

Magnetic Systems: De Haas-van Alphen Studies of Fermi Surface