Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

perfluoropolyether lubricants for magnetic thin-film rigid

disks. J. Info. Storage Proc. Syst. 1, 1–21

Chilamakuri S K, Bhushan B 1997 Optimization of asperities

for laser-textured magnetic disk surfaces. Tribol. Trans. 40,

303–11

Chilamakuri S K, Bhushan B 1998a Contact analysis of non-

Gaussian random surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part J:

J. Eng. Tribol. 212, 19–32

Chilamakuri S K, Bhushan B 1998b Design of sombrero and

donut shaped bumps for optimum tribological performance.

IEEE Trans. Magn. 34, 1795–7

Chilamakuri S K, Bhushan B 1999a Contact analysis of laser

textured disks in magnetic head–disk interface. Wear 230,

11–23

Chilamakuri S K, Bhushan B 1999b Effect of peak radius on

design of W-type donut shaped laser textured surfaces. Wear

230, 118–23

Chilamakuri S K, Zhao X, Bhushan B 2000 Failure analysis of

laser textured surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part J: J. Eng.

Tribol. 1, 303–20

Kajdas C, Bhushan B 1999 Mechanism of interaction and deg-

radation of perfluoropolyethers with DLC coating in thin-

film magnetic rigid disks—a critical review. J. Info. Storage

Proc. Syst. 1, 303–20

Miller R A, Bhushan B 1996 Substrates for magnetic hard

disks for gigabit recording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 32, 1805–11

Peng W, Bhushan B 2001 A numerical three-dimensional model

for the contact of layered elastic/plastic solids with rough

surfaces by a variational principle. ASME J. Tribol. in press

Poon C Y, Bhushan B 1996 Numerical contact and stiction

analyses of Gaussian isotropic surface for magnetic head

slider/disk contact. Wear 202, 68–82

Tian X F, Bhushan B 1996a A numerical three-dimensional

model for the contact of rough surfaces by variational prin-

ciple. ASME J. Tribol. 118, 33–42

Tian X F, Bhushan B 1996b The micro-meniscus effect of a

thin liquid film on the static friction of rough surface contact.

J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 29, 163–78

Zhao Z M, Bhushan B 1996 Effect of bonded lubricant films on

the tribological performance of magnetic thin-film rigid

disks. Wear 202, 50–9

Zhao Z M, Bhushan B, Kajdas C 1999 Effect of thermal treat-

ment and sliding on chemical bonding of PFPE lubricant films

with DLC surfaces. J. Info. Storage Proc. Syst. 1, 259–64

Zhao Z M, Bhushan B, Kajdas C 2000 Lubrication studies of

head–disk interfaces in a controlled environment: Part II.

Degradation mechanisms of PFPE lubricants. Proc. Inst.

Mech. Eng., Part J: J. Eng. Tribol. in press

B. Bhushan

Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Magnetic Recording Devices: Inductive

Heads, Properties

Modern magnetic recording heads are made using the

techniques of integrated circuit fabrication technol-

ogy: photolithographic pattern transfer, selective

thin film deposition and selective thin film etching.

The use of these methods has allowed dramatic

miniaturization of components and increases in

recording densities and operating frequencies. The

first magnetic recording heads had magnetic cores

machined from ferrite and did not use thin film

technology. This approach was used in both magnetic

tape and disk recording until the end of the 1970s,

and was the focus of much invention and miniatur-

ization in its own right.

Then, in 1970, researchers at IBM published a

description of thin film processes that could be used

to fabricate recording heads (Romankiw et al. 1970).

Further refinements led to several patented designs by

IBM (Church and Jones 1980, Jones 1980) and a

transition to thin film technology for head fabrica-

tion in the disk industry, allowing greater degrees

of manufacturing automation and integration. Tape

recording heads followed suit approximately 10 years

later. While begun over two decades ago, this trend

toward greater degrees of integration continues today,

as merged inductive and magnetoresistive (MR) heads

are integrated with secondary mechanical actuators

and trace suspension assemblies. These trends in head

manufacturing are likely to continue for the foresee-

able future, and will be detailed in the ensuing sections

of this article.

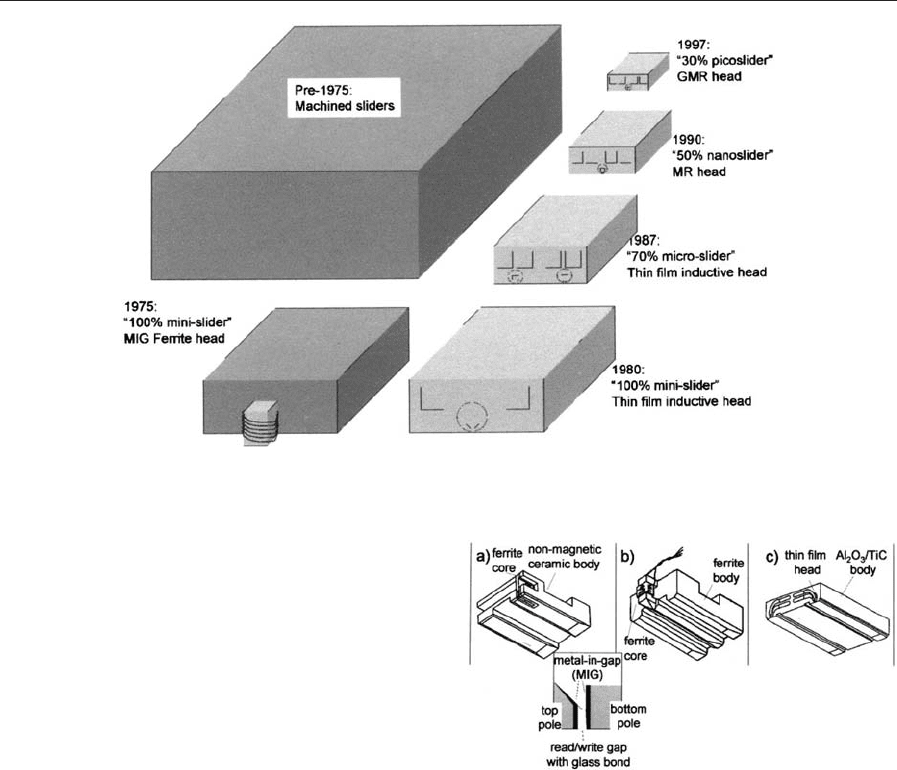

The progress in shrinking magnetic recording heads

through advances in fabrication technology can be

seen in Fig. 1, which shows an outline, to scale, of the

various disk head sliders over the last several decades.

As can be seen the technology has been shrunk by

a factor of three times (in each linear dimension)

since the 1970s. The dimensions given are industry

standards, and are available in Hoyt (1997; see also

Magnetic Recording Heads: Historical Perspective and

Background).

1. Pre-1990s Head Fabrication Technology

1.1 Ferrite Heads

Prior to the advent of thin film head technology,

magnetic recording heads for rigid disk applica-

tions were fabricated using precision machining

techniques from bulk materials, typically magnetic

ferrites. Ferrites are insulators, and, therefore, can be

operated at high frequencies without eddy current

damping. Ferrite heads were the workhorse recording

heads for many years in both tape and disk drives,

serving both the magnetic writing function and the

inductive readback function. MnZn–ferrite and

NiZn–ferrite were the main materials used.

Slider bodies were made of a nonmagnetic ceramic

body to provide mechanical durability. A variation on

this was a ‘monolithic’ head design, introduced by

IBM. This name signified that the entire slider was

machined and assembled from ferrite, reducing the

part count and the number of assembly steps in the

head fabrication. This was made possible by advances

in ferrite technology which permitted them to have

560

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

sufficient mechanical toughness to serve both a mecha-

nical (the slider) and a magnetic function (the core).

This summary is drawn from an excellent discussion of

the ferrite head process in (Ashar 1997, Chap. 4).

As the demands on the recording heads became

more stringent, it became difficult for ferrite to meet

both the frequency requirements and the magnetic

field levels required by the system. Ferrites, while

conveniently insulating, have relatively low values of

magnetization compared to most magnetic metals,

and therefore cannot generate a very large write field.

This situation gave rise to the metal-in-gap (MIG)

head. The MIG design inserts a metal layer (typically

sputter deposited) in the gap of the ferrite core. This

allowed the use of higher induction metals, like NiFe

or Sendust (FeSiAl) for generating higher writing

fields, while continuing to suppress eddy currents in

the large part of the magnetic yoke by continuing to

make them out of ferrite.

The features of these major types of magnetic

heads are illustrated in Fig. 2, which compares a

composite-body head, a monolithic head, and a thin

film head, which represents current (2001) technology

(Ashar 1997). Also shown as an inset in Fig. 2 is a

schematic cross-section of a gap of a MIG head, in

which the additional metal layers are indicated. All

three of these fabrication methods are compared in

Table 1.

1.2 Thin Film Inductive Heads

While MIG heads offered ways to obtain both high

frequency performance and reasonably high writing

fields, they had some serious drawbacks. Chief among

these was manufacturing costs. Most designs had

some degree of hand assembly, which introduced

expense and variability in device parameters. Addi-

tionally, shrinking sizes were harder to produce with

traditional precision machining technology, and the

allowed geometries and materials were limited. Thus,

thin film technology became the preferred method of

device fabrication after the first devices were intro-

duced by IBM in 1970 (Romankiw 1970) and patented

in 1978 (Church and Jones 1980, Jones 1980).

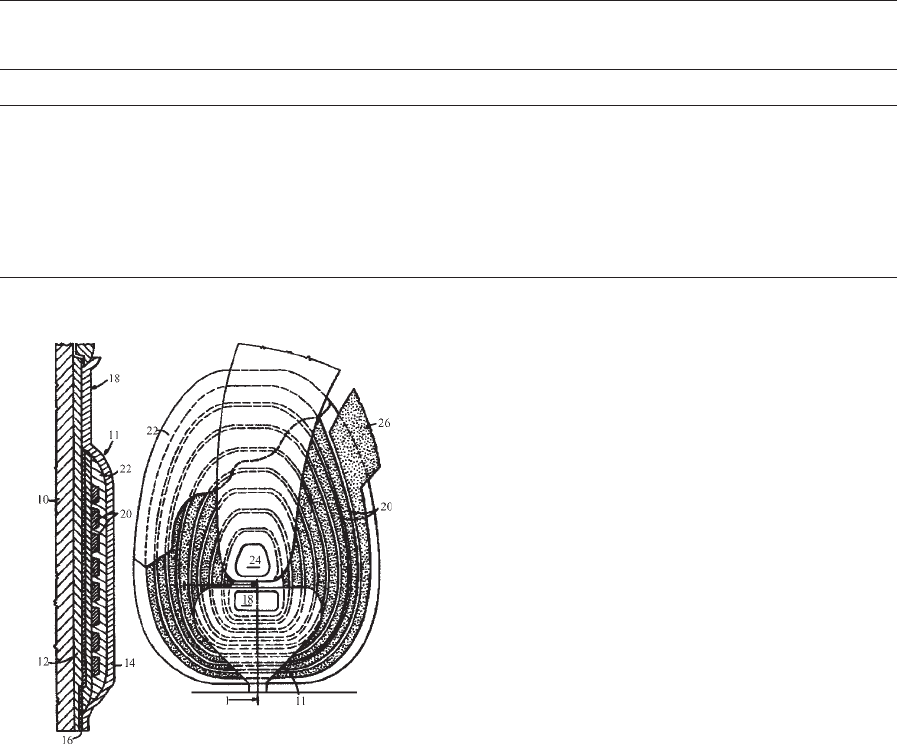

The original patented thin film head design from

1978 is shown in Fig. 3 (Church and Jones 1980).

Like monolithic and composite heads, the first thin

film heads were used both for writing and inductive

Figure 1

Progress in shrinking recording head fabrication over the last 50 years. Parts are drawn approximately to scale.

Figure 2

Types of recording head architectures: (a) monolithic,

(b) composite, (c) thin film (adapted from Ashar 1997).

561

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

readback. This part of thin film write heads has not

changed substantially since its inception, although

dramatic shrinking has taken place. However, in-

ductive writers have been combined with MR read-

back sensors in modern devices, as demonstrated first

in Bajorek et al. (1974). These MR heads will be

discussed in an ensuing section, with detail being

given about the fabrication of both the read and write

parts of the head. The basic structure of the thin film

write head will be summarized here.

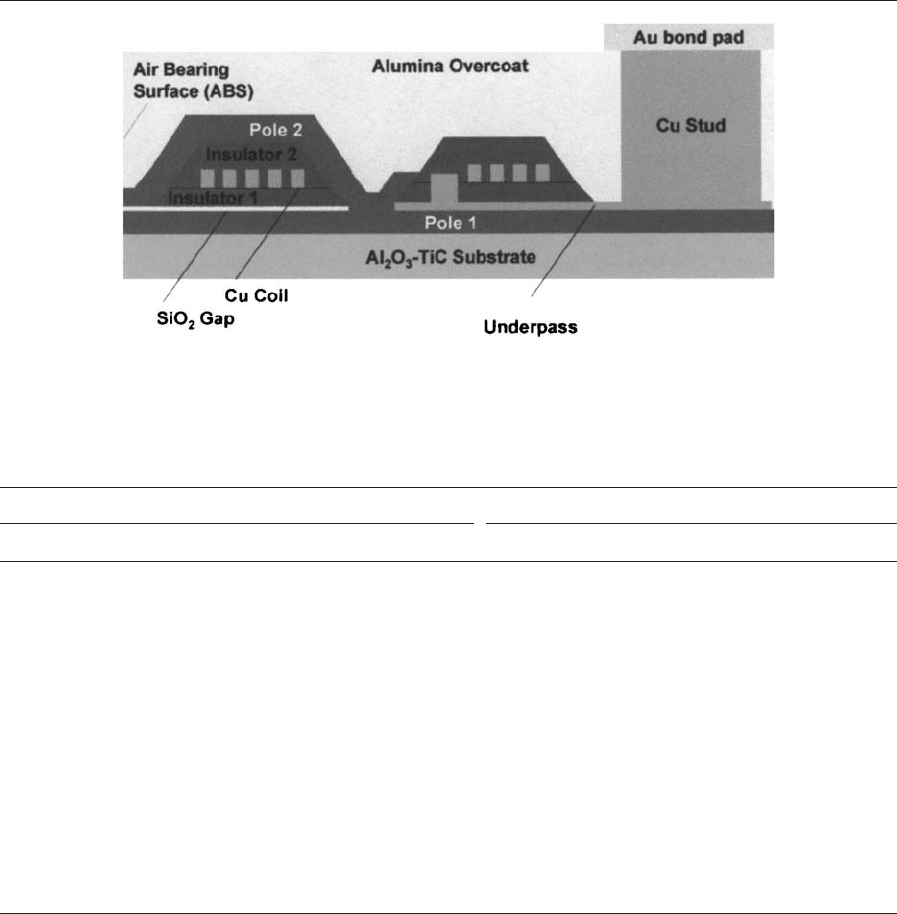

Scrutiny of Fig. 3 reveals that there are six essential

layers in the fabrication of an inductive thin film

head: Pole 1, Underpass, Insulator 1, Coil, Insulator 2,

and Pole 2. These are labeled and shown more clearly

in Fig. 4, which indicates how these layers are

oriented relative to the substrate and the final device.

In addition to the six layers that form the device,

there are a number of packaging and interconnect

layers also indicated in Fig. 4. These include Cu

studs, Al

2

O

3

overcoat, and Au bond pads. All of

these layers will be discussed further in the next

section on merged inductive/MR heads.

While thin film inductive heads enjoyed a number

of years of high volume production as the head of

choice, they were eventually supplanted by heads in

which MR elements were used for readback. There

were a number of limitations to the inductive-only

designs that eventually led to this transition.

The main driver for the obsolescence of inductive

heads was the fact that one head had to serve both

the write and read function. Inevitably this led to

design compromises in which both read and write

functions performed by the inductive core were

suboptimal. For example, in deciding the number of

turns within a thin film inductive design, writing

speed considerations favored a small number of turns

for low inductance. However, readback sensitivity

favors a large number of turns for large inductance

and larger readback voltage. Increasing the data rate

makes this situation worse, and limits the sensitivity

of an inductive readback head, such that the more

sensitive MR heads eventually become necessary. A

summary of the main design tradeoffs in optimizing

an inductive head for both reading and writing are

listed in Table 2.

The transition from inductive read/write heads to

merged MR/inductive heads was delayed by a number

of design and fabrication innovations with the

inductive heads. These innovations mainly focused

on increasing readback sensitivity, without increasing

inductance. Typical of these innovations was the use

of multilevel coils first reported in Tamura et al.

(1990) and eventually extended up to a total of four

levels (Daniel et al. 1999). This approach allowed

more compact coil designs with a lower inductance

and higher efficiency as compared to a design with the

same number of turns, but in a single layer. New

planar yoke designs have also been demonstrated, for

example, the so-called omega-head, with as many as

120 turns (Tang et al. 1994).

Figure 3

Original thin film inductive head from the IBM patent

(Church and Jones 1980).

Table 1

Features of heads fabricated using the major fabrication techniques.

Feature Composite Monolithic Thin film

Magnetic core Machined ferrite

(metal in gap)

Machined ferrite

(metal in gap)

Electroplated or sputter

deposited

Coil Hand-wound or machine-

wound

Hand-wound or machine-

wound

Electroplated

Coil insulation Coated wire Coated wire Photoresist or dielectric films

Slider body Machined ceramic

(nonmagnetic)

Machined ferrite Alumina-TiC

Airbearing Sawed slots Sawed slots Sawed slots or ion milled patterns

562

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

To further increase efficiency, a recessed cavity

design was developed. In this design, the bottom

pole is deposited into a cavity, such that the same

separation between the two poles can be achieved

with less steep slopes in each layer (Zak et al. 1996).

An even more novel design was proposed by Mallary

and co-workers, the so-called diamond head,in

which all the flux threads in each coil turn twice for

greater output (Mallary et al. 1994, Mallary and

Ramaswamy 1993).

2. 1990s Technolo gy: Integrated MR Heads

2.1 Overview of the Head Fabrication Process

Since the late 1980s, the canonical recording head

configuration has been an inductive writer coupled

with a MR reader. As with the original thin film

inductive heads, these heads are constructed using

thin film fabrication techniques. MR heads are used

because they give much better signal to noise perfor-

mance than inductive readers, and the separation of

Figure 4

Basic structure of layers in early thin film inductive heads.

Table 2

Design tradeoffs in an inductive read/write head.

Wafer fabrication Postwafer fabrication

Major steps Description Major steps Description

Bottom shield Photolithographic patterning and

electrodeposition

Rowbar slice Precision sawing

Bottom read gap Vapor deposition and patterning Throat lap Lapping with electrical

feedback

MR sensor and MR

thin leads

Sputter deposition and patterning

with biasing elements

Airbearing pattern Patterning and ion milling

Top MR shield/

Bottom write pole

Vapor deposition and patterning Slider dice Precision sawing

Thick MR leads Vapor deposition and patterning HGA assembly Precision assembly and wire

bonding

Write coil and

insulation

Patterning and electrodeposition

Top pole Patterning and electrodeposition

Leads and studs Patterning and electrodeposition

Alumina overcoat Sputter deposition

Planar lap Lapping/polishing

Bond pads Patterning and electrodeposition

563

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

the two functions allows greater optimization of each

one.

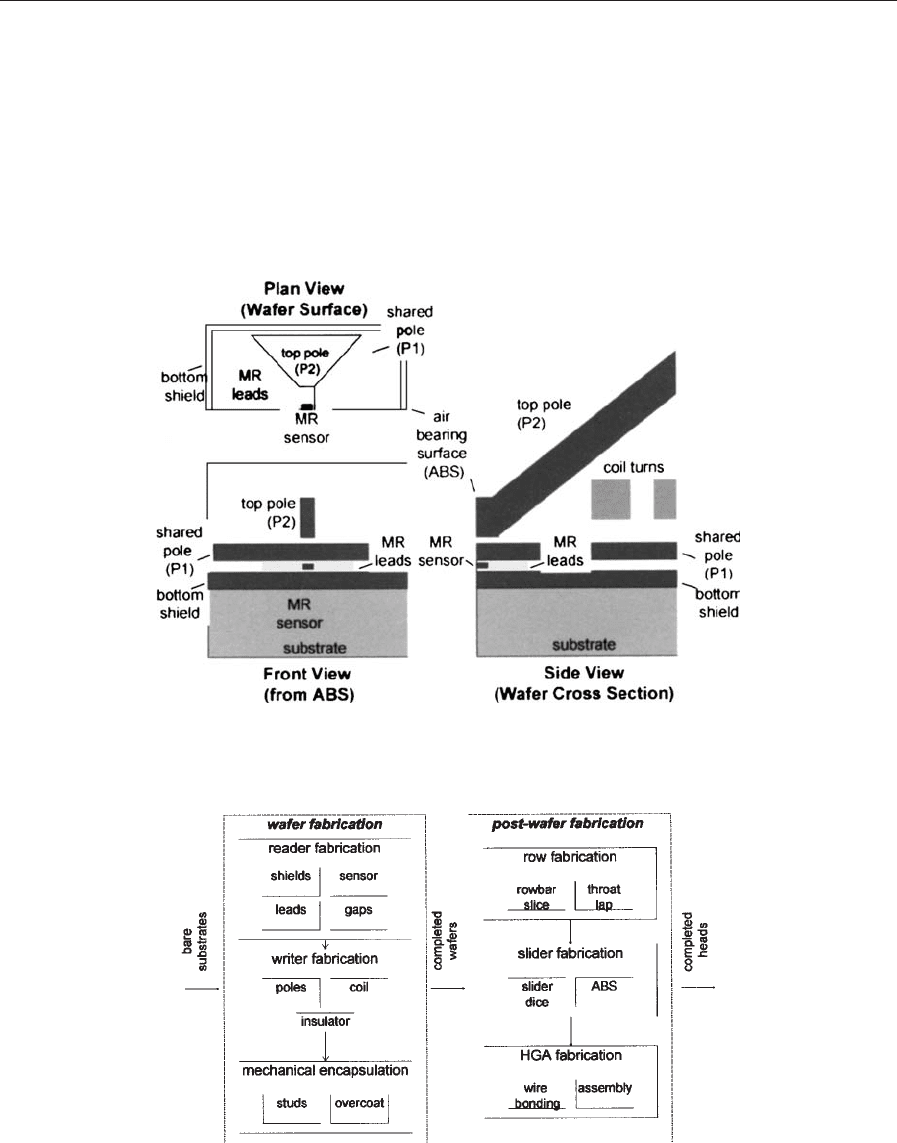

These types of heads are typically referred to as

‘‘merged heads’’ because the reader and writer actually

share one magnetic element. This can be seen in

Fig. 5, which shows a schematic of the active region a

state-of-the-art magnetic head circa 2001. The mag-

netic film that forms both the bottom pole of the

writer and the top shield of the reader is shown. The

hierarchy of the steps in fabricating a merged MR

head are shown in Fig. 6. Each of the following

subprocesses will be discussed below: reader fabrica-

tion, writer fabrication, mechanical encapsulation,

and postwafer fabrication. A tabulation of the major

steps in a typical head process flow is given in Table 2.

While the merged back-of-slider architecture

(e.g., Hannon 1994) represents the vast majority of

commercial heads (c. 2001), a number of other induc-

tive write/MR read head designs have been proposed

and occasionally commercialized on a smaller scale.

Preceding the merged head, a ‘‘piggy-back’’ design

was commercialized in which the top MR shield

Figure 5

Structure of merged MR head (ca. 2001).

Figure 6

Hierarchy of fabrication steps in the construction of a merged MR thin film recording head.

564

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

and the bottom pole were separate layers (Bajorek

et al. 1974, Tsang et al. 1990a, 1990b). Yoke heads, in

which the MR head is separated from the medium

surface by a flux conductor and forms part of a

magnetic circuit have been commercialized. The most

notable was that of the Digital Compact Cassette

(DCC) tape recording system architected by Philips

(Zieren 1993). Silmag, in France commercialized the

planar head on a Si substrate (Lazzari 1974, 1996,

1997), and MR heads in which the current flows

perpendicular to the MR sensor film plane have

been proposed due to their higher giant MR (GMR)

ratio in this geometry (Zhu and O’Connor 1995). All

of these innovations in design required somewhat

different fabrication sequences, but all were built out

of the same basic set of thin film processes. The

details of each of these heads will not be discussed

here; rather a detailed discussion of the fabrication

steps of a merged MR head will be given as

representative of head fabrication in general.

An important concept in the discussion of thin film

device fabrication is that of the critical dimension.

This is the smallest feature that can be reliably

fabricated on the wafer using a particular process.

Recording heads, like semiconductor devices, have

several critical dimension per device, with typically

10000 devices per wafer. Si device wafers can have

billions of critical dimensions per wafer. This will

have important consequences for the feasibility of

certain types of high-resolution fabrication techni-

ques that have a serial nature to them, like electron

beam lithography or focused ion beam etching. These

processes have some application in head fabrication,

while they are expensive to implement in the

semiconductor industry.

There are at least seven critical physical dimensions

in a merged MR recording head. Control of these

dimensions is required to get reliable performance

from the fabricated device. This is accomplished

though careful process design. The seven critical

dimensions are as listed here, and the fabrication

processes used to control them are discussed below.

The read trackwidth and the write trackwidth are the

only two critical dimensions controlled exclusively by

lithography. The MR sensor stripe height, the write

head throat height, and the head medium separation

are controlled by a combination of lithography and

precision mechanical machining. Finally the MR

sensor thickness, MR gap thickness, write gap thick-

ness, and the pole thicknesses are controlled by film

deposition, and are not influenced by lithography.

In addition to critical dimensions in head manu-

facturing, there are also critical alignments. These

include the read to write track alignment and the

alignment of the magnetic to the electrical track-

widths of the MR sensor. Some important processing

advances have been made in addressing the need to

control these alignments.

Finally, in addition to mechanical dimensions and

positions, the material properties of the thin films

from which the heads have been fabricated must be

carefully controlled. These include the sensitivity,

bias point and the stability of the reader, and the

permeability and switching speed of the writer

core. The materials used in these devices are listed

in Table 4.

2.2 MR Read Sensors

(a) Sensor materials

MR heads utilize materials whose resistance changes

with applied field. These may be anisotropic magne-

toresistive (AMR) materials in which the resistance

versus field is given by:

Rðy

AMR

Þ¼R

>;AMR

þ DR

AMR

cos

2

y

AMR

ð1Þ

Table 3

Major steps in the fabrication of modern magnetic recording heads.

Desirable properties for y

Design feature Inductive writing Inductive reading Comment

Pole materials High magnetization for high field High permeability for

sensitivity

Features are not mutually

exclusive but dual

optimization is restrictive

Pole thickness Small for speed large for efficiency Large for sensitivity Fundamental write speed vs.

read sensitivity trade-off

Number of turns Small for speed large for high field Small for resonance large

for sensitivity

Fundamental write speed

versus read sensitivity trade-

off

Fly height Small for resolution Small for resolution Smaller fly height is always

better

Write gap Large for overwrite small for

sidewriting

Small for resolution Fundamental overwrite versus

resolution trade-off

565

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

where R(y

AMR

) is the resistance of the device as a

function of y

AMR

, the angle between the current in

the device and the magnetization. R

>,AMR

is the

resistance of the device when the current and field are

perpendicular to one another and DR

AMR

is the

amount of change in the resistance in going from a

parallel configuration of magnetization to a perpen-

dicular one. Thin films of NiFe show this effect

(DR

AMR

B2%) and have been widely used as sensors.

The sensor materials may also be GMR materials,

in which the resistance of the sensor is given by:

Rðy

GMR

Þ¼R

8;GMR

þ DR

GMR

siny

GMR

ð2Þ

where R(y

GMR

) is the resistance of the device as a

function of y

GMR

, the angle between the magnetiza-

tion in one ferromagnetic layer and the magnetization

in the other. R

8,GMR

is the resistance of the device

when the two magnetizations are parallel and DR

GMR

is the change in resistance of the device when the two

layers change from being parallel to antiparallel.

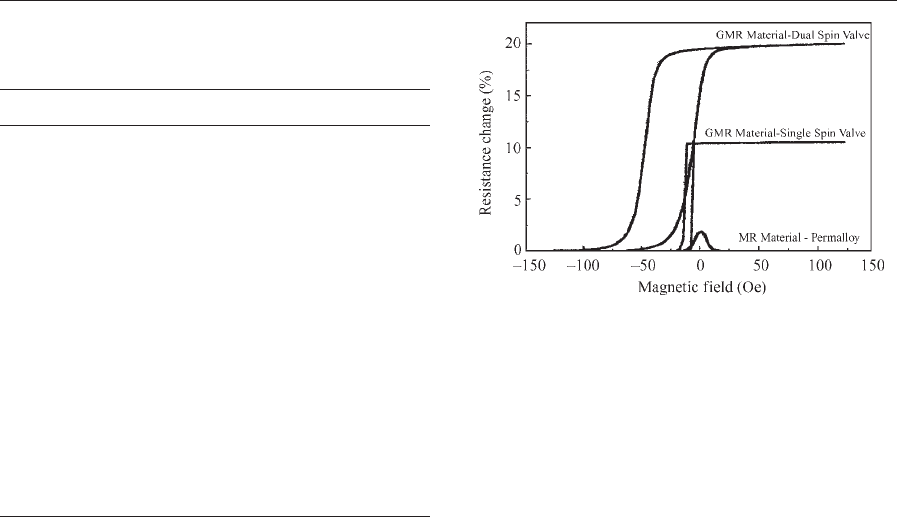

Examples of typical transfer functions for these

devices are shown in Fig. 7 (Brug et al. 1996). It can

be seen that the amplitude of the GMR effect is

typically much larger than the AMR effect (hence the

term ‘giant’), which is the reason for the appeal of

these materials. It can also be seen from this figure

and from the functional forms of Eqns. (1) and (2),

that the transfer functions have very different shapes,

and therefore require different biasing schemes to

achieve linear operation.

This biasing process is typically accomplished

using soft adjacent layers (SALs) or exchange pinning

with antiferomagnets. These layers are typically in-

corporated within the so-called MR stack, such that

the construction of the sensor and the biasing scheme

can be thought of as a single manufacturing step.

This article will not dissect the stack structure and

function in detail as several excellent references exist

on the AMR effect (McGuire and Potter 1975), the

GMR effect (White 1992), and MR head materials

and technologies (Mallinson 1996, Jones et al. 1995).

An excellent review of antiferromagnetic metallic

exchange materials is also available (Lederman 1999),

and developments in synthetic antiferromagnets

(trilayers of Co/Ru/Co patented by IBM, Coffey

et al. 1994) have added enormous flexibility to the

MR fabrication process by eliminating most of the

demagnetizing fields from the biasing layer.

While the deposition of the MR sensor layer

(sensing layer plus biasing layers) can be treated like

a single manufacturing step, consisting of the deposi-

tion and patterning of a composite structure, the

complexity of this step and the associated tooling

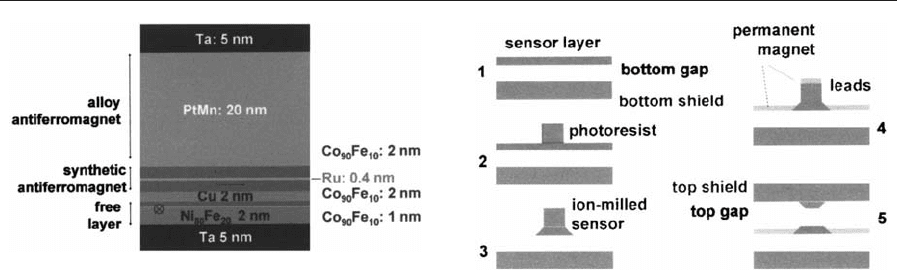

should not be underestimated. A typical stack of

modest complexity is shown in Fig. 8. Note that this

structure consists of nine layers and six different

materials, and the complexity can grow to twice this

for dual spin valves. Deposition tools with 1.5 m

diameter chambers containing six or more 30 cm

diameter targets and costing several million US

dollars are needed for this process.

(b) Shields and gaps

When an acceptable sensor material candidate is

identified, it must be patterned into a sensor and

placed between two insulating shields, to provide

resolution during the readback process. Without

shields, the sensor will pick up magnetic flux from

many bits and not be able to resolve single bits easily.

Table 4

Thin film materials used in the fabrication of magnetic

recording heads.

Component Materials

Substrate Al

2

O

3

/TiC

Poles and shields Ni

80

Fe

20

(permalloy) Ni

45

Fe

55

FeXN (X ¼Al, Ta, Zr) (iron

nitride) FeCoN (iron cobalt

nitride)

Read and write

gaps

SiO

2

(silicon dioxide) SiN (silicon

nitride) Al

2

O

3

(aluminum oxide

or ‘alumina’) AlN (aluminum

nitride)

MR sensors Ni

80

Fe

20

(permalloy) Spin valve

stacks (e.g., NiFe/Cu/NiFe;

CoFe/Cu/CoFe)

Antiferromagnets (e.g., FeMn,

NiMn, IrMn, PtMn, NiO,

CoO)

Coil insulators Photoresist (hardbaked) SiO

2

Leads AlCu Cu

Studs Cu

Bondpads Au

Figure 7

Comparison of different MR sensor responses on the

same scale (from Brug et al. 1996).

566

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

Shields are constructed of electroplated or sputter

deposited thin films, typically 1–2 mm thick, consisting

of materials similar to pole materials. High perme-

ability and magnetic stability is a higher priority in

these materials than is high saturation magnetization,

as the shields conduct signal flux during readback.

Ductility of the shields is undesirable to prevent

smearing of these layers during the mechanical

lapping process (see discussion below under stripe

height definition). This can cause shorting of the

shields to the sensor, rendering it nonfunctional.

A functional sensor is electrically isolated from the

magnetic shields (which are usually electrically

conductive) by a thin insulating gap. Controling the

dimension of this gap, of the order of 100 nm in

thickness, is relatively straightforward, since it is set

by a film thickness. This dimension determines, to a

large degree, the resolution of the head. However,

ensuring that no electrical shorting takes place across

this gap is more challenging. While chemical vapor

deposition of these layers would produce denser films

with better insulation properties, these films are

typically sputtered because this approach can be

done at a lower substrate temperature. GMR films

are particularly temperature sensitive and cannot

typically survive above 250 1C.

(c) Stripe height definition

The definition of the stripe height in an MR head is

accomplished not through optical lithography, but

through a mechanical lapping or polishing process.

Optically defined structures (lapping guides) are used,

indirectly, to control this process, but the physically

polished interface determines the final stripe height.

This process is discussed below in the context of

postwafer fabrication.

(d) Trackwidth definition

The definition of the reader trackwidth involves two

critical dimensions and a critical alignment. Since the

head conducts electrical current and magnetic flux, it

actually has two widths: a magnetic width and an

electrical width. These are the two critical dimen-

sions. Additionally, these two segments need to be

aligned, which constitutes the critical alignment. The

standard way of accomplishing this task that has

emerged is the self-aligned lift-off process. This

method allows two layers to be patterned with the

same photoresist, making the process ‘‘self-aligning.’’

The two layers are the sensor stripe and the electrical

leads. An example of how this is accomplished is

shown in Fig. 9. The permanent magnets used for

longitudinal stabilization are also shown.

(e) Longitudinal stabilization

Longitudinal stabilization of MR sensors is done to

prevent random, nonrepeatable domain activity in

the sensor, which introduces noise into the readback

channel. In today’s devices it is accomplished with

permanent magnet abutted junctions. These perma-

nent magnets are typically incorporated into the self-

aligned lift-off as noted in Fig. 9. This procedure was

patented by IBM in 1991 (Krounbi et al. 1991). These

magnets provide a longitudinal field that helps to

keep the device in a single domain, and prevent

domain wall jumps. The abutted junction is usually

not ideal, and is frequently represented as trapezoi-

dal, (as shown in Fig. 9) due to the etching profile of

the sensor stripe before the permanent magnet and

lead deposition step.

While a close placement of the magnetic material is

good for achieving large fields, it is important to de-

couple (in terms of magnetic exchange) the perma-

nent magnetic from the sensor. If they are strongly

coupled, this introduces noise in the sensor, due to

the nucleation of domain walls by the permanent

magnet grains (Zhu and O’Connor 1996). Permanent

magnet stabilization has also been implemented using

Figure 9

The self-aligned lift-off process typically used for the

definition of read sensor magnetic width, electrical

width, and for accomplishing the alignment of these two

features.

Figure 8

A typical MR stack consisting of a spin valve of modest

complexity. All nine of these layers, consisting of six

different materials, must be deposited in a single

pumpdown.

567

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

overlay techniques, in which an abutted junction is

not formed. Both designs have been analyzed for

performance (Shen et al. 1996) and produced

commercially.

One other widely used longitudinal biasing scheme

was the exchange tab. In this design, material in the

wings of the sensor (outside the trackwidth) was

tightly coupled to an antiferromagnetic layer in this

region (Tsang and Fontana 1982). This rendered

this region like a permanent magnet with the same

magnetization as the active region of the sensor. This

approach has at least two drawbacks. First, the wing

region is not pinned rigidly, so some side reading

occurred due to flux sensing in the tab region.

Second, an exactly matched permanent magnet was

not optimal. In fact typically, permanent magnets

used for longitudinal stabilization have a greater

thickness-magnetization product than the sensor they

stabilize.

2.3 Inductive Write Transducer

(a) Pole materials

The thin film materials used for write head poles need

to satisfy several criteria. First, they need to have

sufficient saturation magnetization, as this sets the

ultimate field they can generate. Second, they need to

be magnetically soft, such that they produce a linear

field response with current, and maintain this perme-

ability up to high frequencies of operation. Current

systems operate in the hundreds of MHz range with

GHz operation frequencies on the horizon. Third,

they need to be compatible with head fabrication

techniques. For example, they cannot require proces-

sing temperatures above 250 1C. Finally, they need to

be magnetically and chemically stable for a long

period of reliable operation.

A list of the main candidates for thin film pole

materials is given in Table 5. These materials are

sorted in order of saturation magnetization, M

s

, rang-

ing from 800 kAm

1

in permalloy to 1900 kAm

1

in

FeCoN. Steady increases in pole magnetization have

made writing on higher coercivity media possible. In

the right most column of Table 5 is listed the

maximum coercivity of the media that a head with

the given pole composition could write on. This ratio

between the magnetization and the maximum long-

itudinal media coercivity (measured at room tempera-

ture and at long time scales) is about 4:1.

All of the materials in this list have been made in

highly permeable forms. Maintaining high magnetic

permeability at high frequency requires two things.

First, eddy currents must be suppressed. Eddy

currents occur when the skin depth of the material,

d becomes less than half the film thickness. At this

point, the center of the film (most distant from the

surface) is shielded from the applied current and

ceases to switch. Pole permeability consequently falls

off. The skin depth, d is given by:

d ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

r

2pf m

r

m

0

r

ð3Þ

where r is the material electrical resistivity, f is the

operation frequency, m

r

is the relative permeability of

the material (unitless) and m

0

is the permeability of

free space (H/m). The above equation suggests that

high resistivity materials are the only practical

solution, as frequency is a given and a reduction of

permeability is generally undesirable for magnetic

functionality.

Increasing film resistivity is accomplished in one of

two ways: adding elemental constituents or laminat-

ing. In either case, a reduction of the saturation

magnetization, M

s

, generally occurs because of the

introduction of nonmagnetic material. Lamination

with insulating layers (by analogy to power trans-

formers and other 60 Hz devices) is more predic-

able in its effects on high frequency permeability than

alloying, and generally improves the magnetic do-

main configuration of the layers. However, it is much

less compatible with electrodeposition (the preferred

method of pole fabrication from a cost perspective)

than alloying.

A second requirement at high frequencies is the

rapid damping of magnetic precession. This ensures

Table 5

Pole materials.

Material Media

Composition Name Deposition method Ms (kAm

1

) Hc Max (kAm

1

)

Ni

80

Fe

20

Permalloy Plating, sputtering 796 199

FeAlSi Sendust Sputtering 955 239

Ni

45

Fe

55

Plating, sputtering 1114 279

CoZrX Sputtering 1194 298

FeXN Fe-Nitride Reactive sputtering 1592 398

FeCo Plating, sputtering 1910 477

568

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties

that the magnetization actually switches, rather than

simply precessing at the frequency of interest. While

the actual ferromagnetic resonance frequency, $

FMR

,

can be pushed to higher values by proper design,

increasing the damping is presently not a well-

understood process. The FMR resonance frequency,

$

FMR

, is given approximately by:

$

FMR

Eg

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

M

2

s

m

r

s

ð4Þ

where g is the gyromagnetic constant (HzmA

1

), M

s

is the saturation magnetization of the film, and m

r

is

the relative permeability of the film (unitless). From

this relationship, it can be seen that resonant

frequency can be increased by raising M

s

(desirable)

or decreasing m

r

, (undesirable).

The above considerations are relevant to choices

made in the head fabrication process. As seen in

Table 5, the two main options for pole deposition are

electroplating and sputter deposition. Plating has the

advantages that it tends to have higher throughput,

require lower cost tools, produce films with lower

stresses, and facilitates finer line patterns, since it

is an additive rather than a subtractive process.

Sputtered materials have the big advantage that

laminating with insulators is simple within a sputter

deposition system. Until now, there has been very

little commercialization of sputtered materials in disk

heads. (Tape heads use them regularly for their

superior wear resistance.) This is because the cost of

processing and the ability to cheaply fabricate narrow

tracks have dominated the tooling decisions.

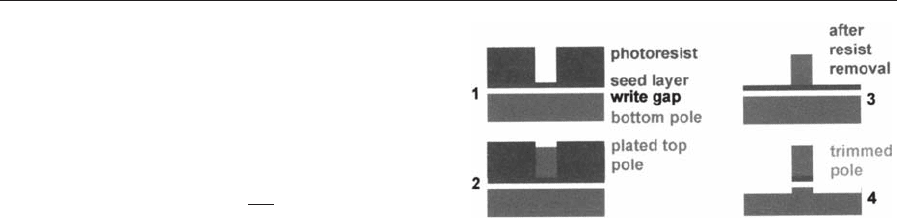

(b) Trackwidth definition

Definition of the write trackwidth is perhaps the

single greatest challenge of the modern writer

process. This is because of the large aspect ratios of

these devices. In some cases a submicron lateral

dimension is needed on a 2–3 mm thick feature. As a

general rule, aspect ratios of this type are difficult in

planar lithographic processes. Typically, the top pole

is electroplated into a photoresist mask to give a

high aspect ratio, then ‘‘trimmed’’ after photoresist

removal, to give a top and bottom pole that are close

to the same width, and well-aligned. This is another

self-aligning process, and is shown schematically in

Fig. 10.

(c) Coil formation

The fabrication of coils in heads is typically through

electrodeposition (or ‘‘plating’’) of Cu into photo-

resist dams. An electrically conductive seedlayer

(50–100 nm thick) is needed, as in the electrodeposi-

tion of poles, in order to preferentially plate where

the coil needs to be formed. After plating 1–2 mmof

Cu into the photoresist dams, all of the turns of the

coil are shorted together by the seedlayer. Thus it is

removed by ion milling. An insignificant amount of

the coil themselves is removed in this process as

well. In high performance inductive writers, there is a

push toward fewer turns, short yokes, and coils

that are less complicated than those used in inductive

read heads. This trend allows a very low inductance

head to be constructed, which has good high-speed

performance.

2.4 Electrical Connection and Mechanical

Encapsulation

After a head is electrically complete, it must be

mechanically processed to expose the sensor at the

edge of the slider. This requires that the head be

encapsulated in a thick layer of electrically insulating,

mechanically robust material. Typically, sputtered

alumina is used, because it can be made thick with

low stress and, therefore, low propensity for delami-

nation. It is, however, a somewhat time consuming

process, taking typically several hours to deposit the

required 20 mm thick films.

Electrical connection through the encapsulation is

necessary to contact the devices, and this is typically

done with a composite stud-bond pad structure. The

studs are 20 mm thick posts of Cu that are electro-

plated before the deposition of the alumina. A

mechanical planarization process, like lapping or

chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP) is used to

expose the Cu after the alumina deposition. Finally,

the exposed Cu contact regions are covered with Au

bond pads to facilitate the connection of the head

leads and to prevent Cu corrosion.

2.5 HGA Construction: Postwafer Fabrication

After the wafer is complete, it is diced into rows, and

these are lapped to create the correct stripe height in

the MR head and the correct throat height in the

inductive writer. Since this is a single operation that

sets two critical dimensions, the alignment of the zero

Figure 10

Electrodeposition of the top pole followed by pole

trimming at the wafer level.

569

Magnetic Reco rding Devices: Inductive Heads, Properties