Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

layer in many cases. Special precautions must be

taken because of ESD (electrostatic discharge). Pre-

cise photo-processing and etch techniques are needed.

In spite of these exacting requirements, spin valve

heads are manufactured by the million using ad-

vanced manufacturing techniques unavailable before

the end of the 1990s. It is the dominant sensor in

magnetic recording.

In 1995 the concept of a head architecture using the

shields as leads on the top and bottom of a sensor in

the CPP mode was proposed (Rottmayer 1994,

Rottmayer and Zhu 1995). This configuration can

be used with both a CPP GMR multilayer or MTJ

(magnetic tunnel junction) sensor.

The CPP GMR head consists of a number of layer

pairs of GMR material, e.g., copper/cobalt as shown

in Fig. 17. The interlayer coupling across the copper

is relatively small so that the coupling is primarily

magnetostatic. The GMR DR/R is 2–4 times the DR/

R in the CIP direction and can be as high as 100%.

The device is placed between two shields, which also

serve as leads. This confers a large degree of ESD

protection since all parts of the device are at approx-

imately the same potential.

A single bias magnet is placed behind the sensor.

This is an advantage over the leads and magnets that

must be attached to the sides of a spin valve head

since it is much easier to fabricate and control track

width. The CPP GMR is a low-impedance device

having a resistance of only a few ohms even at den-

sities of 100 Gb/in

2

. This can result in a low signal

amplitude. However, the CPP GMR has the advan-

tages that its resistance increases with the square of

the track width (TW) and so as densities increase, the

resistance is in a more favorable range.

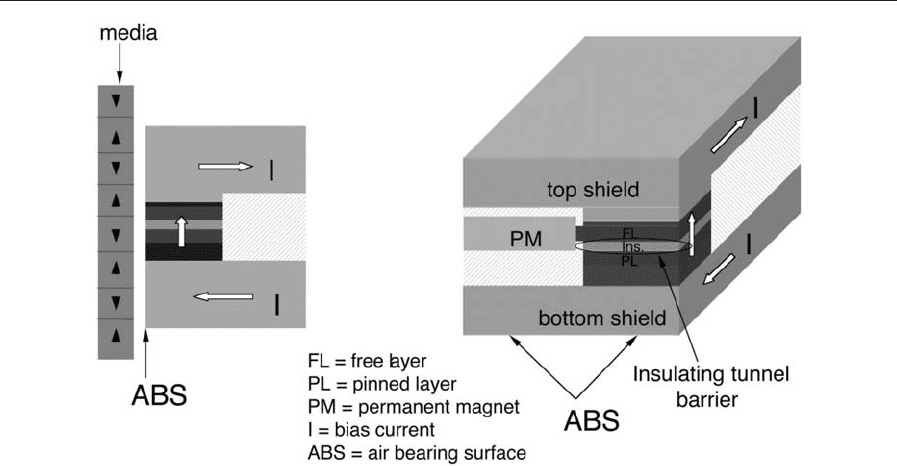

The MTJ device is made by sandwiching a thin

insulating layer of alumina between two ferromag-

netic metal layers, one of which is pinned as in a spin

valve as shown in Fig. 18. Electrons can tunnel

through the thin (o2 nm) barrier. Since they are spin-

polarized, the current is larger when the magnetiza-

tion of the two FM layers is parallel. DR/R ratios of

more than 25% have been reported for MTJs.

In contrast to the CPP GMR head, the MTJ has a

high resistance of about 1 kO at 100 Gb/in

2

. The MTJ

requires longitudinal stabilization with a magnetic

field; however, this does not require that the magnet

be in contact with the MTJ and so it enjoys the same

advantages as the CPP GMR as far as ease of fab-

rication and track width definition. The thin barrier is

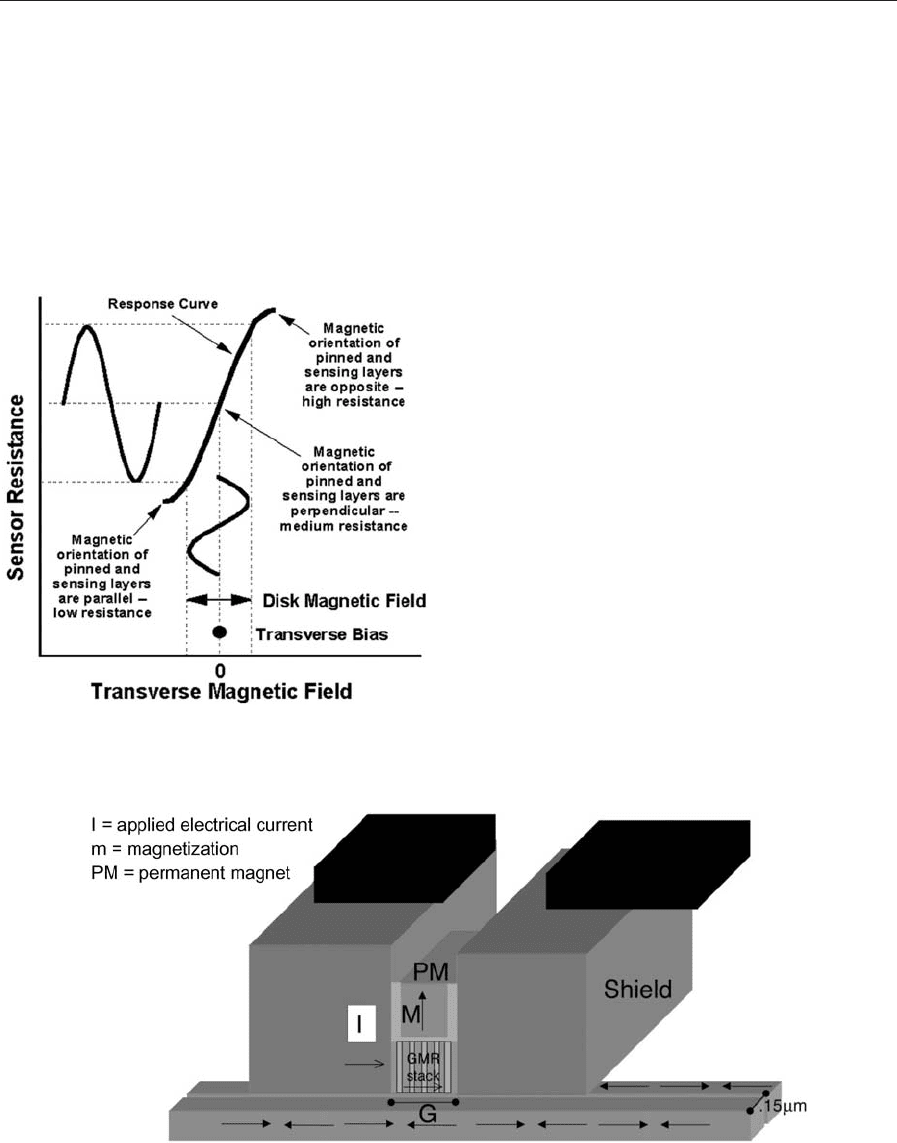

Figure 17

CPP GMR head (after Rottmayer and Zhu 1995).

Figure 16

GMR sensor response to disk magnetic field (courtesy of

IBM Corporation).

580

Magnetic Reco rding Heads: Historical Perspective and Background

susceptible to ESD and this will be a challenge for use

in disk drives.

5. The Future of Magnetic Recording Heads

Magnetic recording heads have answered the chal-

lenges of the data storage market place from the IBM

Ramac (2.6 Kb/in.

2

) to today’s drives of approxi-

mately 20 Gb/in

2

. This represents an increase in areal

density of seven orders of magnitude in 45 years. This

has been accomplished primarily by scaling—that is

reducing the dimensions of the head, as the bits be-

came smaller. The high leverage scaling parameters

were the fly height, the gap length track width, and

core size. In conjunction with this, scaling advances

in materials also contributed. Most notable was the

change from bulk-ferrite to thin-film magnetic mate-

rials and the development of GMR sensors for

increased output. Semiconductor-like batch fabrica-

tion processes have reduced the costs while simul-

taneously improving performance. What does the

future hold?

Head media spacing (HMS) continues to be a key

parameter in increasing areal density. With today’s

fly heights close to 10 nm and an additional 5–7 nm of

disk overcoat, head protection, and lubrication film,

we are approaching a regime where we are getting

close to the physical limits of the proximity of two

materials. In addition, other considerations such as

media thickness limit the advantage of lower fly

height as we get into the nm region. So gains will be

limited by HMS in the future.

In the area of head critical dimensions (CD), the

acceleration of the areal density race has led to a

convergence between the semiconductor line-width

roadmap and the head-track-width roadmap. At the

present rates of growth, the two curves will intersect

early in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

The head industry has traditionally relied on the

semiconductor industry to develop the lithography

equipment and processes.

If the track density of magnetic recording contin-

ues to outpace the line-width reduction of semicon-

ductors then the head industry will no longer be able

to depend solely on the semiconductor industry for its

technology. However, there are lithographic technol-

ogies that can push track widths more than an order

of magnitude from current production. There are also

alternative architectures such as putting the trans-

ducer on the side of the slider and allowing the depo-

sition thickness to determine the track width.

Gaps and sensor thicknesses are defined by depo-

sition processes which can be extended to much high-

er areal densities. The most important problem at this

time is thin insulating layers needed both for gap

layers in SPV heads and for the tunnel barrier on

MTJ heads. Both the rapid advances in deposition

technology and the variety of alternative architec-

tures mentioned above show great promise in ex-

tending head areal densities.

Sensor sensitivity can be extended by further im-

provement in SPV heads and the use of alternative

technologies such as CPP GMR and MTJ heads. The

frequency capability of the write head is now the

Figure 18

Magnetic tunnel junction read head.

581

Magnetic Reco rding Heads: Historical Perspective and Background

major problem in higher data rates. Improved mate-

rials, geometries, and architectures can extend fre-

quency limits of the write head. The switching

frequency of the head may be ultimately limited by

ferromagnetic resonance in the head materials.

The biggest problem in recording-head design to-

day is providing heads with the capability to write

higher media coercivities and thus push back the su-

perparamagnetic limit. Perpendicular recording with

a soft underlayer can help overcome this problem.

Also, thermally assisted magnetic recording can low-

er the coercivity of the media during writing thus

enabling the writing of a pattern more stable at

operating temperatures. Whatever the architecture

used, the density can be extended by increasing the B

s

of the pole materials. Thus there is much active

research on materials with B

s

42.4 T. It is, however,

not clear that such materials exist in a form suitable

for head poles.

Even though magnetic recording is pushing some

physical limits and certain fabrication limits men-

tioned above, there still exist many paths to increase

areal density and data rates. Heads play a key role in

both areas. With the many alternatives available to

increase areal density and data rate, magnetic re-

cording should continue to improve in performance

with magnetic recording heads playing a key role.

See also: Magnetoresistive Heads: Physical Phenom-

ena; Magnetic Recording Devices: Future Technolo-

gies; Magnetic Recording Devices: Inductive Heads,

Properties; Magnetic Recording: Rigid Media: Over-

view; Magnetic Recording Technologies: Overview;

Micromagnetics: Basic Principles

Bibliography

Baibich M N, Broto J M, Fert A, Nguyen Van Dau F, Petroff

F, Eitenne P, Creuzet G, Friederich A, Chazelas J 1988

Giant magnetoresistance of (001) Fe/(001) Cr magnetic

superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2472–5

Bhushan B 1999 Micro/Nano Tribology, 2nd edn. CRC Press,

Boca Raton, FL

Betram H N 1994 Theory of Magnetic Recording. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge

Betram N H, Williams M 2000 SNR and density limit esti-

mates: a comparison of longitudinal and perpendicular re-

cording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 36, 4–9

Daniel E C, Mee C D, Clark M H 1999 Magnetic Recording:

The First 100 Years. IEEE Press, New York

Hoagland A S, Monson J E 1991 Digital Magnetic Recording,

2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Karlqvist O 1954 Calculation of the magnetic field in the ferro-

magnetic layer of a magnetic drum. Trans. R. Inst. Technol.

86,22

Mee C D, Daniel E D 1996 Magnetic Storage Handbook, 2nd

edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Rottmayer R, Zhu J 1995 A new design for an ultra-high den-

sity magnetic recording head using a GMR sensor in the CPP

mode. IEEE Trans. Magn. 31 (6), 2597–9

Rottmayer R 1994 Magnetic head assembly with MR sensor.

US Patent 5 446 613

Rottmayer R, Spash J L 1976 Transducer assembly for a disc

drive. US Patent 3 975 570

Wang S X, Taratorin A M 1999 Magnetic Information Storage

Technology. Academic Press, New York

White R M 1984 Introduction to Magnetic Recording. IEEE

Press, New York

R. E. Rottmayer

Seagate Research, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Magnetic Recording Materials: Tape

Particles, Magnetic Properties

The basic principles of magnetic recording and in-

formation storage have remained unchanged for

more than a century. The initial machines used steel

wire as the recording medium, but in 1928 Pfleumer

patented a paper tape coated with iron filings and a

magnetophone using this tape was demonstrated in

the 1935 Berlin exhibition. During the World War II,

plastic tapes coated with magnetic particles were

developed in Germany and since then the basic

structure of the modern magnetic storage tape has

remained unchanged. Certainly there have been in-

novations, improvements in performance and prop-

erties of the media, and a range of different formats

and methods of storing the information, but the basic

structure of magnetic particles embedded in a non-

magnetic matrix on a plastic substrate has remained

the same.

When considering analog recording, it is not ob-

vious what the fundamental properties of the mag-

netic medium should be. In all analog systems a linear

relationship is required between the signal and the

magnetization and this is usually achieved by a.c. bias

to use the anhysteretic remanence properties of the

magnetic components. The a.c. bias is superimposed

on the signal in the case of analog audio systems, but

is self biasing when frequency modulation is used in

analog video recording.

The fundamental properties of the magnetic medi-

um becomes more obvious when digital storage is

considered. Here, information is stored as one of two

states (in simple terms corresponding to the binary

states of digital bits) and it is clear that the compo-

nents used to make up the magnetic medium must

also have two discrete magnetic states. If the medium

is composed of particles, then these particles should

be capable of being switched between two states with

an easy axis which can be magnetized in either of two

directions. These particles are single domain and ide-

ally should have a square hysteresis loop. In addition,

since the information must be stored indefinitely or

until erased, the energy barrier between these two

582

Magnetic Reco rding Materials: Tape Particles, Magnetic Properties

states should be of sufficient height to prevent ther-

mal decay of the information or accidental erasure.

Modern data systems require very high aerial den-

sities of information to be written at very high rates.

In order to accommodate the higher densities, there

is a continual move towards thinner magnetic layers

and to higher coercivitiy particles. For analog audio

and video formats, magnetic layer thickness of

several microns consisting of ferrite particles were

adequate. For the latest advanced data storage tapes

metal particles have replaced the earlier ferrites

allowing coercivity to be pushed up to in excess of

2 kOe and magnetic layer thickness down to hun-

dreds of nanometers.

Magnetic properties are also dependent on the time

scale so that writing at high frequencies confronts the

dynamic switching time of particles resulting in much

higher coercivities than those involved in the long-

term storage. This is becoming more of a problem as

data rates increase. Time dependence of magnetiza-

tion is, therefore, crucial to magnetic information

storage properties at both ends of the time scale—at

high frequencies the time to switch a particle is a

limiting factor whereas for long-term archival of

information, thermally activated decay of magneti-

zation presents a problem. All these properties will be

considered in this article.

1. Magnetization Reversal

(the Origin of Coercivity)

1.1 Single Domain Particles

Bulk magnetic materials will divide up into domains.

This has the effect of reducing the total magnetic en-

ergy contribution. However, because energy is asso-

ciated with a domain wall, for small particles it is

energetically preferable for the particle to remain as a

single domain and, with the associated anisotropy

resulting from the shape and the intrinsic crystal

properties of the material, the single domain mag-

netization will lie in preferred directions. In the case

of hexagonal or uniaxial anisotropy, there are two

easy directions and the particle is said to have an easy

axis. (See also Magnets, Soft and Hard: Domains,

Coercivity Mechanisms .)

1.2 Coherent Reversal

The Stoner Wohlfarth model (Stoner and Wohlfarth

1948) was the first successful attempt to describe the

hysteresis behavior of a particle. Although the pre-

dicted coercivity was much larger than that observed

in experimental systems, the simplicity of the model

allowed a mathematical description of the reversal

and the model is still used as a means of describing

particulate systems and is a good model for visual-

izing the reversal process. Stoner and Wohlfarth

(1948) and Cullity (1972) provide a full description of

the model. In the model, reversal is regarded as a

coherent process where all the individual spins rotate

in unison.

The particle moment is, therefore, single valued

and can rotate relative to the particle axis. Crystal

and shape anisotropy of the particle will determine

the energy associated with different orientations of

the particle moment and result in an energy barrier

between minimum energy positions. For a uniaxial

system, these energy minima are opposite each other

and the system has a particle easy axis and, in the

absence of an external magnetic field, the energy is a

minimum when the moment is pointing along the axis

or in the opposite direction. At an angle y, then the

energy can be written approximately as

E ¼ K

1

Vsin

2

y ð1Þ

where K

1

is the anisotropy constant, V is the particle

volume, and KV is the height of the energy barrier.

Given the potential energy of interaction of the par-

ticle moment with an external field and expressing the

anisotropy constant in terms of the anisotropy field

as

K

1

¼ H

K

M

s

=2 ð2Þ

where H

K

is the anisotropy field and M

s

is the sat-

uration magnetization of the particle, then the energy

associated with the magnetic moment of the particle,

m, in an applied field H at an angle f to the particle

axis can be written as a 2D expression as

E ¼ m½H

K

sin

2

y=22Hcosðy2fÞ ð3Þ

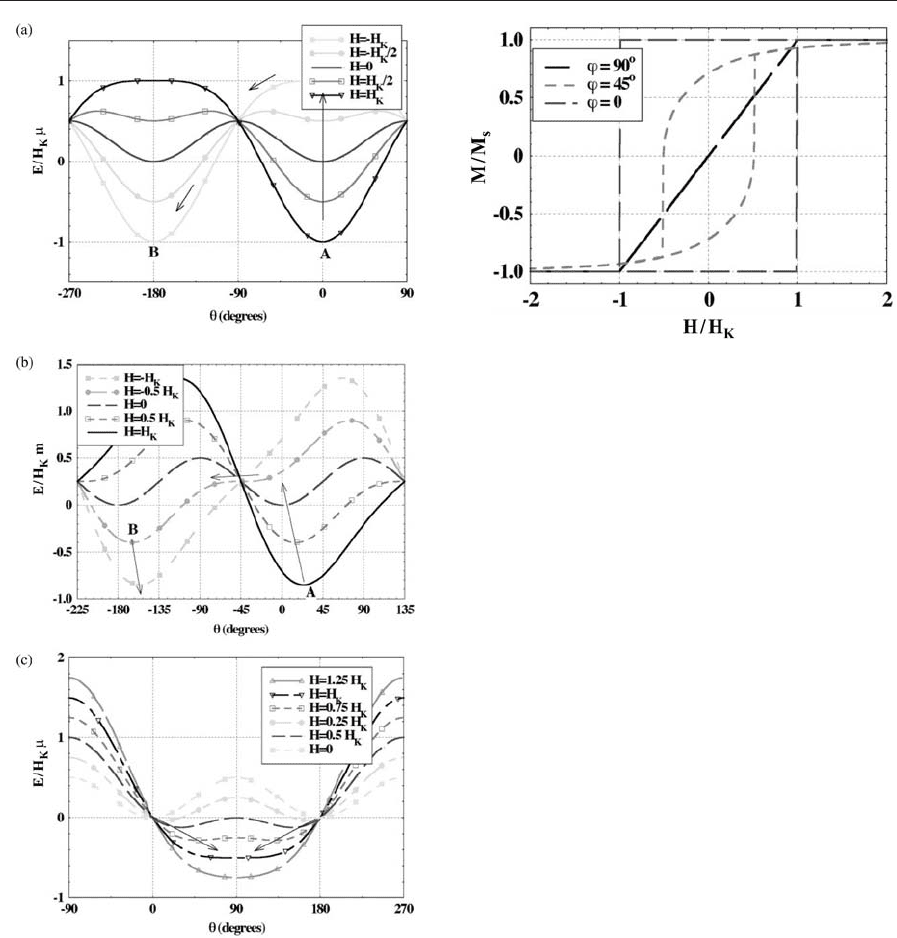

Visualizing the reversal process for different

orientations of the particle is straightforward and a

number of examples are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1(a)

shows the energy of a moment as a function of angle

for various fields applied in the direction of the par-

ticle easy axis. Consider the moment at y ¼0 in a field

H

K

. The moment will be in the energy minimum at A.

As the field is reduced the moment will remain at

y ¼0 until H ¼–H

K

when the equilibrium position

becomes unstable and thermal fluctuations will

switch the moment direction to 1801 at position B.

It will remain in that direction until the field is in-

creased to þH

K

. Thus, the particles will exhibit a

square hysteresis loop (Fig. 2). Figure 1(b) shows the

case where the applied field is at 451 to the particle

easy axis. At high positive fields the particle moment

will lie along the field direction.

However, note that when the field has been re-

duced to H

K

, the energy minimum at A has moved

towards the easy axis direction. As the field is reduced

further, the energy minimum becomes shallower and

moves towards y ¼0 and at HB–0.5 H

K

it disappears

so that the moment will switch to position B and then

move towards the field direction as the field becomes

583

Magnetic Reco rding Materials: Tape Particles, Magnetic Properties

more negative. The whole process is reversed when

the field change is in the positive direction and this

produces a hysteresis loop with reversible, but field-

dependent, magnetization at fields in excess of the

coercivity. Figure 1(c) shows the case when the field

direction is at rights angles to the easy axis. In this

case no switching occurs but the two energy minima

merge to produce a single flat bottomed minimum at

H ¼H

K

. Hysteresis loops for all three conditions are

shown in Fig. 2 obtained by a numerical solution of

the Stoner Wohlfarth model.

1.3 Superparamagnetism

The energy barrier to reversal is proportional to the

particle volume so that as the size of the particle is

reduced, the height of the barrier moves into the

thermal regime when the particle moment can be

switched by thermal energy alone and the time for

reversal, t, is given by the Ne

´

el-Arrhenius law (Ne

´

el

1949):

T

1

¼ f

o

expð2E

b

=kTÞð4Þ

where f

o

is a frequency factor usually taken as B1

10

9

, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and E

b

is the height of

the energy barrier. The particle is then said to be

superparamagnetic. The onset of superparamagnet-

ism is not only dependent on the shape and size of the

particle but is also related to saturation magnetiza-

tion and the anisotropy constant.

1.4 Incoherent Reversal

In practice, coherent reversal is only observed for

very small particles and recording tape particles are

sufficiently large that the normal reversal mode is

incoherent. In this case, the energy is minimized dur-

ing reversal by reducing the magneto-static energy

Figure 2

Hysteresis loops for a Stoner Wohlfarth particle for

applied field directions of 01,451, and 901 to the easy

axis.

Figure 1

Energy of a particle moment as a function of angle to

the easy axis direction when the magnetic field is

applied in different directions: (a) along the easy axis,

(b) at 451 to the easy axis, and (c) at right angles to the

easy axis.

584

Magnetic Reco rding Materials: Tape Particles, Magnetic Properties

between individual spins through their misalignment.

There are various simple models for this incoherent

reversal and the two most commonly referred to are

fanning and curling whose names graphically de-

scribe the particle motion during the reversal process.

1.5 Interaction Effects in Particle Systems

In recording media, magnetic properties are deter-

mined by the mean behavior of all the particles in the

system. Particles will have a range of volumes and

shapes which will produce a distribution of switching

properties. In addition, particle orientation will be

spread around an axis determined by magnetic ori-

entation along the tape during manufacture. These

will produce a switching field distribution which is

further modified by the magneto-static interactions

between particles due to their close proximity and the

long range of the dipole–dipole interaction. A study

of single particle properties from optical observation

of magnetic reversal of single particles and compar-

ison of simulated magnetic tape properties with

measured properties indicated a very large shift in

the switching field distribution (McConochie et al.

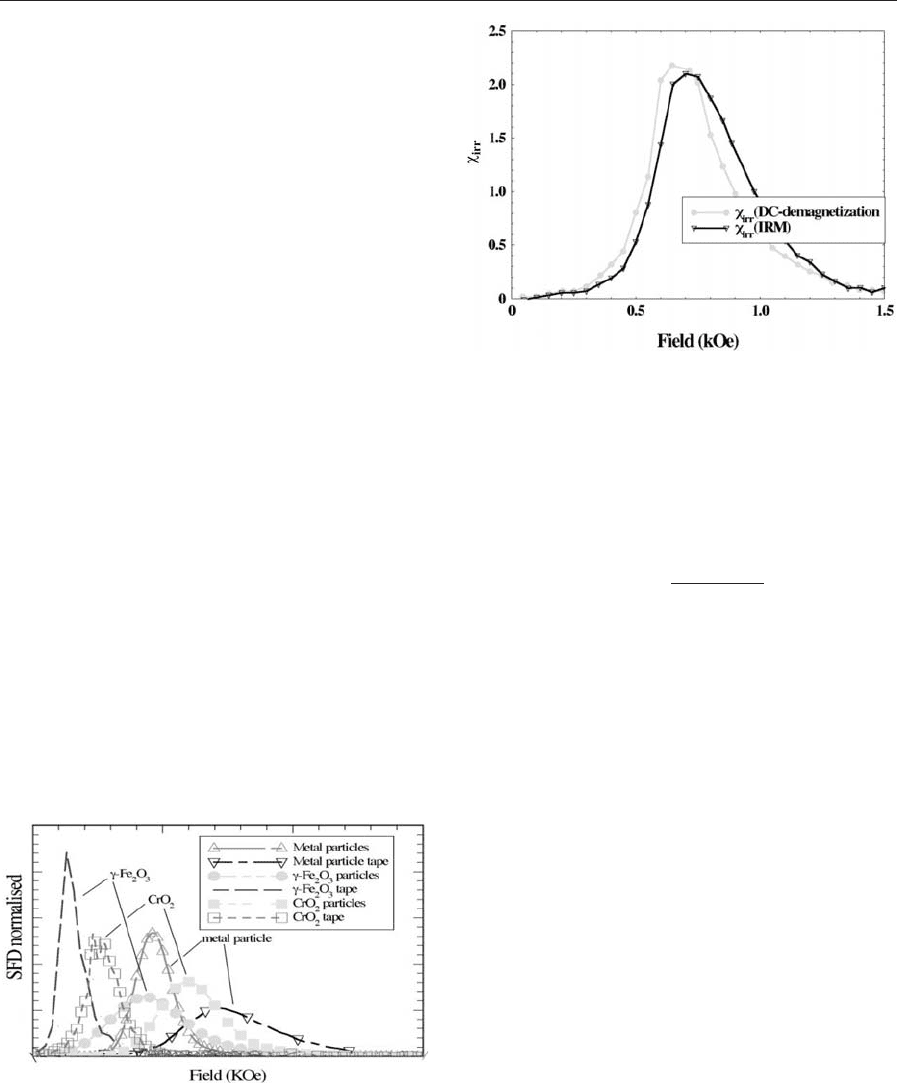

1996). Figure 3 shows results for such a system in

which the displacement of the switching field distri-

bution due to interactions can be seen.

Because of interaction effects, the switching field

distribution of a system varies between processes. In

Fig. 4 switching field distributions for the isothermal

remanent magnetization and the d.c. demagnetiza-

tion processes are shown for a cobalt modified g-

Fe

2

O

3

video tape. These curves are also referred to as

the irreversible susceptibility curves because they are

measured in the remanent state so that changes are

only due to irreversible switching properties. These

susceptibility distributions have been normalized so

that the area under the curve is unity. Any magnet-

ization state can then be represented by an integral of

these distributions as

MðHÞ¼

R

H

0

wðHÞdH

R

N

0

wðHÞdH

ð5Þ

where w(H) is the susceptibility.

2. Time Dependence

The previous discussion has been in terms of static

properties of media. However, thermal activation

can cause moments to switch over energy barriers

and will produce time-dependent changes in magneti-

zation. This was first investigated by Street and

Woolley (1949) who observed a logarithmic decay as:

M ¼ const 2 S lnðtÞð6Þ

where S is the magnetic viscosity coefficient and is

dependent in the applied magnetic field (see Magnetic

Viscosity). Although this relationship does not hold

over very short and very long time scales, it is found

to be applicable over several decades of time and

gives a reasonable description of time-dependent be-

havior in most cases. The magnetic viscosity coeffi-

cient is field dependent and is related to the number

of moments which are in an energy minimum within

the thermal range.

Intuitively it would be expected that the maximum

S would occur close to the center of the switching

field distribution (i.e., near to the coercive field) and

that the variation of the viscosity coefficient would be

closely related to the switching field distribution. This

Figure 3

Switching field distributions simulated for an ensemble

of tape particles and the measured switching field

distribution showing the shift in properties produced by

the interaction effects.

Figure 4

Switching field distributions for a cobalt-modified g-

Fe

2

O

3

video tape measured for isothermal remanent

magnetization and d.c.-demagnetization processes.

585

Magnetic Reco rding Materials: Tape Particles, Magnetic Properties

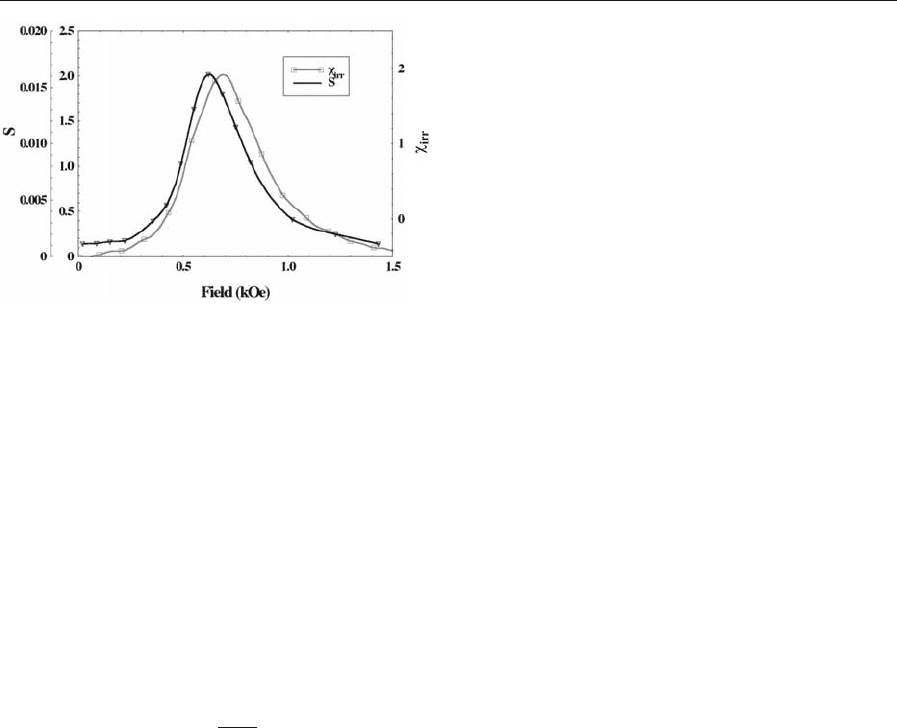

is indeed found to be the case and Fig. 5 shows the

variation of S with field along with w

irr

obtained from

the d.c.-demagnetization curve for the cobalt g-Fe

2

O

3

video tape. Because of the intuitive link between S

and w

irr

, Street and Woolley proposed a parameter

called the fluctuation field, H

f

defined by:

S ¼ w

irr

H

f

ð7Þ

The fluctuation field was associated with the

concept of an activation volume, V

ac

by Wohlfarth

(1984) where

H

f

¼

kT

V

ac

I

s

ð8Þ

and I

s

is the saturation magnetization of the bulk

material. The interpretation of the fluctuation field

and activation volume is difficult as they do not relate

to any physical media properties. However, the ac-

tivation volume is often taken to represent the vol-

ume of the particle which is involved in the initial

reversal process. This does seem to have some basis as

activation volumes are generally smaller than the

particle volume and can be considered as the volume

of the region in which reversal is first propagated

during an incoherent process. However, this is not

always the case, and sometimes activation volume

can exceed the particle volume which seems physi-

cally unreal.

3. Concluding Remarks

Intrinsic magnetic properties of tape particles and the

recording process have remained unchanged through-

out the history of magnetic recording. However, to

accommodate the need for higher data densities and

faster switching there has been a move to thinner

magnetic layers and higher coercivity particles. The

earlier ferrite particles are now being replaced by

metal particles in the high density advanced data

storage systems.

See also: Magnetic Recording Media: Advanced;

Magnetic Recording Technologies: Overview; Metal

Particle versus Metal Evaporated Tape; Micro-

magnetics: Basic Principles

Bibliography

Cullity B D 1972 Introduction to Magnetic Materials. Addison

Wesley, Reading, MA

McConochie S R, Schmidlin F, Bissell P R, Gotaas J A, Parker

D A 1996 Interaction effects from reversal studies of single

particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 155, 89–91

Ne

´

el L 1949 The

´

orie du trainage magne

´

tique des ferro-

magne

´

tiques en grains fins avec application aux terres cuites.

Ann. Geophys. 5, 99–136

Pfleumer F 1928 German Pat. DRP 500 900

Stoner E C, Wohlfarth E P 1948 A mechanism of magnetic

hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Roy. Soc. Phil. Trans. 240,

599–642

Street R, Woolley J C 1949 A study of magnetic viscosity. Proc.

Phys. Soc. A. 62, 562–72

Wohlfarth E P 1984 The coefficient of magnetic viscosity.

J. Phys. F. 14, L155–9

P. R. Bissell

University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK

Magnetic Recording Measurements

Magnetic recording devices use materials that exhibit

spontaneous magnetization in their operating tem-

perature range: ferromagnets and ferrimagnets (see

Magnetic Recording Technologies: Overview). The

magnetic properties of these materials can be classed

into two categories: properties that are determined by

composition and crystal structure, denoted intrinsic;

and properties that depend on microstructural factors

such as grain size and shape in a polycrystal, or par-

ticle shape and orientation in a composite, denoted

extrinsic. Both intrinsic and extrinsic magnetic pro-

perties are functions of environmental factors such as

electric and magnetic fields, temperature, pressure,

and atmosphere.

The measurements described below depend on the

scale on which they view the magnetic property to be

measured. The microscopic scale focuses on a mag-

netic material as an arrangement of interacting

atoms and interprets magnetic properties in terms

of spin and orbital moments, energy levels, binding

energies, spin–orbit, exchange, and superexchange

Figure 5

Variation of the magnetic viscosity coefficient for a

cobalt-modified g-Fe

2

O

3

video tape showing the peak

close to the coercive field value.

586

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

interactions, etc. The mesoscopic scale averages these

microscopic interactions over small homogeneous re-

gions (grains, particles) comprising many atoms. Av-

erages over many such (interacting) regions constitute

the macroscopic properties of the magnetic material.

An important consideration in measuring the mag-

netic properties of a material is its uniformity. In-

homogeneities may occur on the microscopic scale

(point defects such as vacancies and interstitials, line

and planar defects such as dislocations, or composi-

tion fluctuations in disordered alloys), on the me-

soscopic scale (grain or particle clusters, voids, and

segregations), and on the macroscopic scale, given the

limits on quality control in fabrication.

1. General Measurements

In most instances, magnetic measurements described

below are extrinsic measurements made by measuring

a sample’s response to an externally applied magnetic

field. The measurements can depend on the sample’s

shape: the inhomogeneities and discontinuities of

the magnetization in the sample’s interior and on its

surface are sources of a magnetostatic demagnetizing

field that depends on the sample’s shape and that

affects the internal field. As the internal magnetiza-

tion changes in response to applied fields, tempera-

ture, or time, the internal field will also change due

to the changing demagnetizing fields. These fields

can also be microstructure dependent because typical

polycrystalline or particulate materials exhibit effects

due to grain boundaries and particulate or grain

orientation.

These measurements are also affected by the rate at

which the magnetic field is changing (viscosity and

eddy current effects) and how long it takes to make

the measurements. Indeed, the magnetization of all

materials will eventually seek the lowest energy state,

if we wait long enough at any nonzero temperature.

In the absence of an applied field this is always a state

of demagnetization with zero net magnetization when

summed over the whole sample volume, because such

a demagnetized state minimizes the magnetostatic or

dipolar self-energy. We conclude that the sample’s

coercivity, defined as the field that must be applied to

a magnetized sample to reduce its magnetization to

zero, is zero for infinite-time measurements! At the

other end of the time scale we might try to coerce the

spins in a magnetic material to change directions with

a short field pulse.

We are concerned here with the magnetic proper-

ties of electron spins but, as the word implies, spins

are associated with angular momentum, and exhibit

the (quantum mechanical) inertial effects of angular

momentum. Moreover, spins are usually coupled to

each other and to their surroundings, and thus spin

dynamics exhibits spring-like inertial and damp-

ing effects. Put another way, spins do not change

instantaneously but take time to alter their direction.

In general, if the magnetization is to be changed a

given amount (say from a magnetized to a demag-

netized state) in a shorter time, this will require a

larger externally applied field. Measured coercivities

are larger for shorter applied field times.

Measurements then need to be described by the

applied field rates of change and are generally

grouped in three regimes: sl owly varying fields,

quickly varying fields, and pulsed fields. Th e field s

may be lo calized, uniform over l arge areas, or chang-

ing in sp ace (field gradien ts). The measurements

can interrogate a small re gion of a whole or an entire

large sample. (See also Magnetic Measurements:

Quasistatic and ac.)

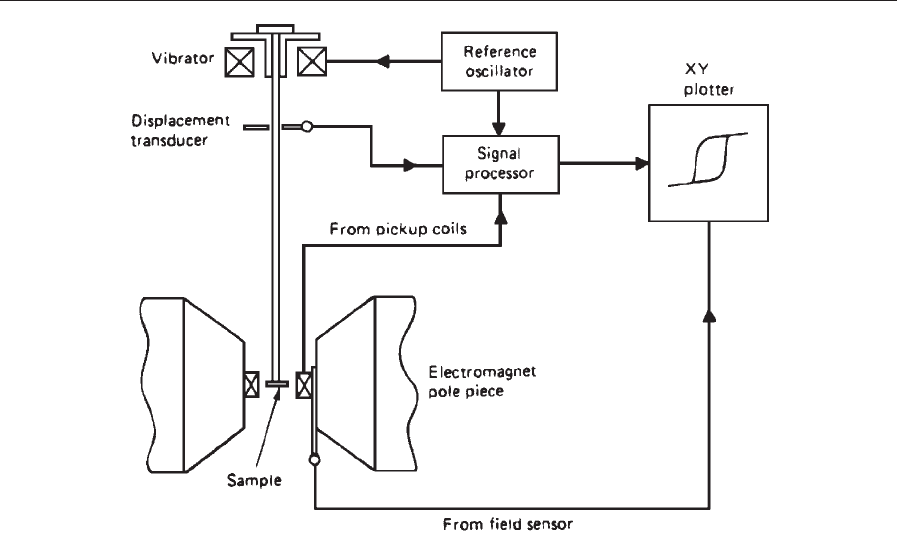

1.1 Vibrating Sample Magnetometry

Developed in the late 1950s by S. Foner, the vibrating

sample magnetometer (VSM) continues in wide-

spread use for measuring magnetic properties of ma-

terials including thin films and particulate media. The

basic technique involves a large-scale applied field,

using an electromagnet to immerse an entire small

sample in a nearly uniform field (Fig. 1). The field is

swept slowly (usually less than mTs

1

) and the sample

is moved (vibrated) in the applied field. As described

previously, the magnetic sources associated with a

sample’s geometry and magnetization cause internal

magnetostatic fields and of course external fringing

fields. Inductive pick-up coils are placed in close

proximity to the sample, inside the applied field, and

sensed synchronously with the motion of the sample.

The assumption is made that the external fields

are proportional to the net internal magnetization

(modified only by the geometry of the sample, i.e., its

demagnetizing factor) but since this is a large-scale

measurement, internal domain structure may affect

the measurement.

1.2 AGFM

Another approach to generating macroscopic mag-

netic parameters is the alternating gradient force

magnetometer (AGFM). Its salient feature is the

ability to trace a major hysteresis loop in seconds

rather than minutes as with a VSM.

1.3 a.c. Hysteresis Loop Measurement

If the interrogating magnetic field is applied rapidly

and repetitively, usually at 60 Hz or 1 kHz, the sam-

ple’s major hysteresis loop can be detected and traced

synchronously. In this method, the sample is station-

ary and the field changes rapidly causing the mag-

netization and its resulting fringing field to change at

the rate of the applied field. Differential inductive

pickup coils are typically employed to sense these

587

Magnetic Recording Measurements

fringing fields and the average magnetization is as-

sumed to be proportional to them. Measurements are

made considerably faster than with a VSM. As dis-

cussed previously, these faster measurements can

produce measured values of coercivity larger (by tens

of percent) than those obtained from a more slowly

varying VSM measurement.

1.4 Torque Magnetometry

If a sample’s average magnetization is not aligned

with an applied uniform magnetic field, a torque will

be created on the sample through its magnetostatic

energy (as described above) and its magnetocrystal-

line energy, the energy associated with the orientation

of the spins relative to the material’s crystal lattice. A

material may have a preferred easy axis of magnet-

ization, through a macroscopic shape, mesoscopic

particulate or granular alignment, magnetocrystalline

anisotropy, or other phenomena. To examine internal

anisotropies, a large, static magnetic field is applied

to a sample with uniform demagnetizing factors (ide-

ally an ellipsoid of revolution). As the sample is ro-

tated in this field, the magnetization does not

completely align with the applied field because of its

internal anisotropy. The resulting torque on the sam-

ple is measured and recorded as a function of sample

rotation angle. A typical method includes suspending

the sample on a torsional wire or glass fiber, and

small torsional angles are measured optically using a

reflecting mirror attached to the suspension and op-

tical lever enhancement. These data can be used to

determine the form (uniaxial, cubic, or other) of the

anisotropy and its magnitude as a function of applied

field.

1.5 Magneto-optical Measurement

Instead of measuring the external fringing fields

and inferring the average magnetization from them,

the samples may be probed optically. The Faraday

or Kerr effects are incorporated into these systems

and very small samples or small sample areas of

larger samples can be examined. These magneto-

optical methods utilize the interaction of light with

a magnetic material (see Magneto-optics: Inter- and

Intraband Transitions, Microscopic Models of ). The

customary system measures the rotation of the plane

of polarization or induced ellipticity of a light beam

(often from a HeNe laser) as the linearly polarized

light ray passes through (Faraday) or reflects off

(Kerr) the sample. For the former, linearly polarized

light passes through samples and the electric field of

the light interacts with the transverse magnetization

and induces an electric field orthogonal to both the

planes of polarization and magnetization. This is

Figure 1

VSM illustration (schematic).

588

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

particularly effective for samples whose magnetiza-

tion is collinear with the applied light. The rotation

for magnetization parallel to the direction of pro-

pagation is opposite that for magnetization anti-

parallel to the propagation direction. To overcome

the reduction in amplitude from material absorption,

transparent materials or thin magnetic films need to

be used for the Faraday measurement to be practical.

The Kerr effect employs a similar phenomenon

associated with the interaction of the electric field

with the sample’s magnetization. The interaction in-

duces a secondary electrical field that alters the light’s

initial polarization. In this technique, linearly polar-

ized light is reflected from a magnetic material’s

surface. Since the angle of incidence is usually not

normal, the s- and p-polarizations interact diffe-

rently with the magnetization and by examining the

rotation and ellipticity, in-plane and perpendicular

(polar) magnetizations can be measured.

These magneto-optical measurements can be made

at any speed with which the magnetization can be

changed, from subnanoseconds to hours. The light

can be spread to average large sample areas or

focused to subdiffraction limited spots using near-

field optics. Since microscopic measurements can be

made rapidly, this technique is often employed to

determine a sample’s degree of uniformity.

1.6 Magnetoresistance Measurement

Transport properties of films used in magnetic re-

cording for transducer applications are measured to

predict device performance. Typically, the resistivity

of unpatterned films of magnetoresistive materials is

measured using a four-point probe technique. Typical

four-point probes use an in-line geometry but mag-

netoresistance measurements are best done with a

rectangular configuration with the current applied

along the long side of the rectangle and the voltage

measured along the other long side of the configura-

tion. The measurements are made in a varying applied

magnetic field. The output is normally expressed as

the ratio of the difference of the resistivities measured

with the magnetization along the current direction

(r

:

) and transverse to it (r

>

), to the average resis-

tivity; i.e.,

r

ave

¼

r

:

r

>

1

3

r

:

þ

2

3

r

>

The field that saturates the film or device, the aniso-

tropy field H

k

, together with the magnetoresistance

ratio, forms the figure of merit, or usefulness. The

amount of resistance change per applied field is often

the quantity of interest. A device having a 50%

change in resistance at several tesla may not be as

useful to a system as one that has a 2% resistance

change at less than a millitesla.

1.7 Magnetostriction Measurement

As a sample’s magnetization is changed the material

may deform and similarly as a material is stressed the

magnetization may be affected. This phenomenon of

magnetostriction is important for magnetic recording

media and transducer fabrication, since stresses

developed in these materials during deposition or

patterning, or temperature-induced stresses due to

thermal expansion mismatches between materials

including the substrate, can dramatically affect the

properties and performance of the materials and de-

vices. To measure these effects on films for magnetic

recording applications, film samples are typically

prepared on substrates that are not perfectly rigid.

The sample is placed in uniform applied magnetic

fields that cause the sample to bend due to differential

strains of the film and substrate. These small bends

can be measured effectively using optical reflection:

the position of a light spot specularly reflected off the

sample’s surface is monitored as a function of applied

field (see Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale Hetero-

geneous Materials).

1.8 Electron Microscopy

Since the introduction of magnetic force microscopy

(MFM, see below) using an electron beam for imag-

ing magnetic structure has been rendered largely ob-

solete because of the difficult sample preparation

necessitated by electron microscopy. To the extent

that it is still used, magnetic contrast in the electron

microscope can be classified into three categories:

scanning electron microscope (SEM), Lorentz deflec-

tion microscopy in the transmission electron micro-

scope (TEM), and electron holography.

There are two basic modes of magnetic contrast in

the SEM, denoted as type I and type II magnetic

contrast. In these modes, the electron beam interacts

with the sample and the fringing magnetic field. Type

I contrast comes from polar magnetization through

Lorentz force effects on the secondary electrons. In

one orientation, the Lorentz force will cause more

electrons to drift toward the detector while the

opposite magnetization will force the secondary elec-

trons away from the detector. Type II contrast im-

ages in-plane magnetization when the sample is

rotated along an axis collinear with the magnetiza-

tion. This technique involves number contrast with

the backscattered electrons. As the electrons come

near the sample the Lorentz force due to the mag-

netization will cause more electrons go toward the

sample for one orientation while the other magnet-

ization direction will force the electrons out, away

from the sample. For these electron beam techniques,

samples need to be clean and conductive (to reduce

charging) and are placed in a vacuum. Spatial reso-

lution of 50 nm is readily achieved but a quantitative

measure of magnetization is impossible to obtain.

589

Magnetic Recording Measurements