Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Transmission imaging in the TEM uses Lorentz

forces as the electron beam passes through the sam-

ple. This diffraction contrast method is sensitive to

in-plane magnetization and uses a defocused electron

beam image. Imaging domains and domain ripple are

the premier application for TEM Lorentz micro-

scopy. Since the beam needs to pass through the

material, samples must be thin and conductive, and

usual techniques for vacuum sample preparation

need to be observed. Submicron spatial resolu-

tion for this method can be achieved but higher res-

olution imaging can be very difficult.

Electron holography uses the interference effects as

some of the electrons pass through a perturbing

fringing field. These fields may even be from a mag-

netized sample of an energized device such as a re-

cording head. The Lorentz force causes the electron

path, integrated along the field, to deflect it from its

nominal path. (See also Magnetic Materials: Trans-

mission Electron Microscopy.)

1.9 Magnetic Force Microscopy

Developed from the 1986 Physics Nobel Prize win-

ning development of the scanning tunneling micro-

scope (STM), magnetic force microscopy (MFM)

uses a small magnetic probe tip that scans over an

area of a sample’s surface. The tip first measures the

sample’s mechanical surface detail, then retraces the

surface measuring the interaction between the mag-

netized tip and the fringing fields emanating from the

sample’s surface. In contrast with the original STM

that requires a vacuum, MFM is typically performed

in ambient conditions. As with most of the techniques

described the measurement only senses the external

fields. This necessarily means that the magnetization

within the sample is not known directly and can only

be inferred.

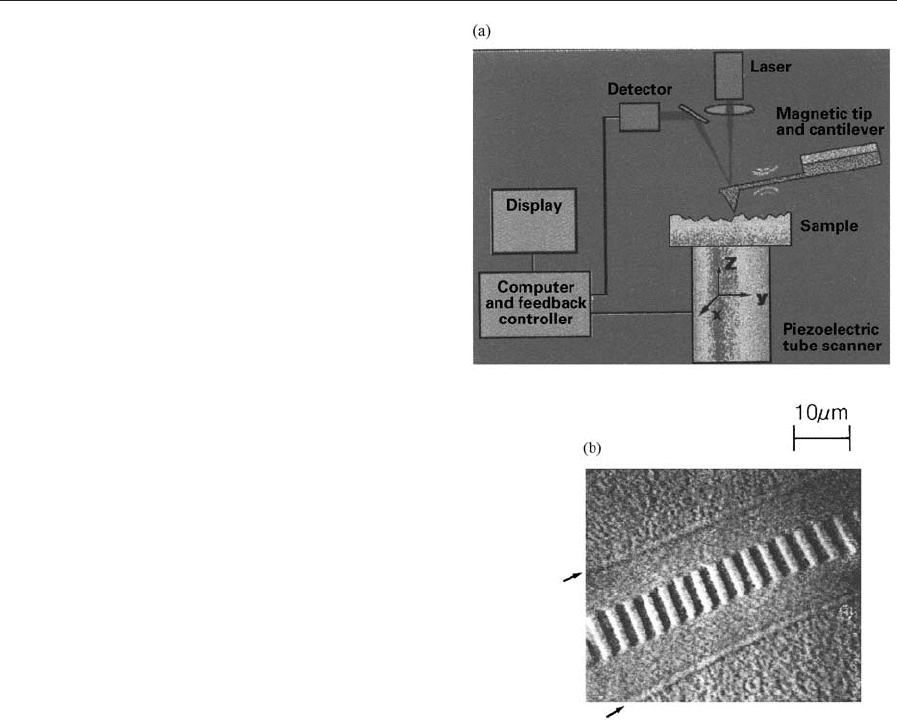

In a typical measurement, a micromachined can-

tilever with a pyramidal tip coated with a ferromag-

netic film is vibrated at resonance (Fig. 2(a)). The

fringing fields from the medium interact with the

ferromagnetic tip shifting the tip’s resonance. This

frequency change is related to the strength and di-

rection of the fringing field and the resolution is lim-

ited by the gradient of the magnetic field and the

geometry of the tip. Quantitative MFM output is still

being developed. The spatial resolution of this tech-

nique is currently about 30 nm. Images take several

minutes to produce and are typically less than 100

micrometers square. The images are usually taken in

remanence but techniques for making measurements

at applied fields have been developed and are be-

coming widely used.

A striking example of the power of the method is

shown in the image (Fig. 2(b)) of a track written on a

longitudinal medium. The image displays not only

the written bits and the transitions between them; it

also shows the contrast between the d.c.-erased re-

gion on which the track was written, a region which is

at remanence with its relatively uniform magnetiza-

tion, and the surrounding demagnetized region, with

its randomly magnetized and hence noisier grain

structure. (See also Magnetic Force Microscopy.)

Figure 2

MFM illustration (schematic and typical output). (a)

Schematic of a scanning probe microscope (MultiMode

design). For magnetic imaging, the probe has a magnetic

tip. The sample is moved in a raster pattern by the

piezoelectric scanner, and the sample’s stray fields cause

shifts in the resonance of the cantilevered probe that are

measured by laser detection. (Copyright r 1994

PennWell Publishing Co., Tulsa, OK. Reproduced with

permission.) (b) MFM image (reproduced by permission

of the American Institute of Physics from J. Appl. Phys.,

1990, 68, 1169).

590

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

2. General Recording

As a context for the application of magnetic meas-

urement techniques to recording measurements, we

begin with a brief outline of the various forms of the

magnetic recording process. This context is necessary

for an understanding of the relation between the

measured macroscopic magnetic properties and the

recorded signals. This includes such obvious relations

as that between the amplitude of the signal and the

remanence of the recording medium, or the medium

coercivity and the demands on the saturation mag-

netization of the head, the less obvious effect of me-

dium coercivity and saturation magnetization on the

transition width in digital recording setting a bound

on the bit cell size, and such subtle effects as the

degree of intergrain exchange interaction on the noise

properties of polycrystalline films.

2.1 Analog and Digital Recording

Analog recording still dominates consumer audio and

video apparatus. In the standard audiotape cassette

system, a carrier (called the a.c. bias) is amplitude

modulated at the audio frequency and partially mag-

netizes a thick magnetic coating of the tape. The

portion of the coating magnetized is linearly pro-

portional to the audio signal. In the various video

recording schemes, a frequency-modulated carrier

saturates the tape, and the signal is recorded and

detected in the zero crossings.

Digital magnetic recording is the standard in data

storage and instrumentation recorders, is becoming

so in professional audio and video recording, and has

begun making inroads in consumer audio and video.

In digital systems, the information is quantized and

represented as a sequence of binary bits. The bits are

recorded and sensed as transitions between saturated

regions, usually along narrow tracks of magnetic tape

or disk.

2.2 Anhysteretic Remanence

The media bearing magnetically recorded informa-

tion are stored under ambient conditions. This means

that their magnetic state is a remanent state from

whatever magnetic history they have been subjected

to, ordinarily not a state linearly related to the most

recently experienced magnetic field. In saturation re-

cording, the state is the conventional remanence,

which is independent of the most recently experienced

field, if that field was large enough. When linearity is

required, as in analog audio recording, the linearity

is provided by the a.c. bias field. In the presence of

the bias field, the remanent magnetization is a func-

tion of the modulating field known as the anhystere-

tic remanence. The anhysteretic remanence curve is

a linear function of the modulating field for small

values of that field, and the linear range is largest for

bias fields near the medium coercivity.

2.3 Erasure

The virtually universal practice in saturation record-

ing is direct overwriting. The write head field is de-

signed to have a value several times the medium

coercivity, so that any previously written information

is wiped out. Incomplete erasure of track edges does

present some problems, which are addressed by

methods (servo, coding) discussed elsewhere.

Erasure is an essential requirement in linear audio

recording, where any existing recorded signal would

not be completely overwritten by the new informa-

tion. The standard practice is to provide the trans-

ducer with a separate erase head. This head has a

wider gap than the write or read heads, so that its

field is assured of penetrating through the full thick-

ness of the medium. The erase can be either d.c. or

a.c. In d.c. erase, a large steady head field leaves the

medium saturated, obliterating any existing informa-

tion. In a.c. erase, a large oscillating field is gradually

reduced to zero, leaving the medium demagnetized.

In practice, a.c. erasure is achieved with an oscillating

field of constant amplitude; the decrease of the field

occurs as the tape leaves the head region.

2.4 Tape and Disk

Tape and disk storage have kept pace with increases

in density and speed. Magnetic tape is polyethylene

tape coated with a magnetic particulate or film me-

dium. Signals are recorded on tape in linear, helical,

or transverse tracks. The tape is stored on reels or

cassettes. Magnetic disks are flexible (diskettes) or

rigid. Flexible disks are made of polyethylene, usually

coated with a particulate magnetic medium, and en-

closed in a protective package. Rigid disks are al-

uminum alloy or glass, now universally coated with

continuous magnetic films. Information is recorded

in circular tracks.

Tape has the advantage of low cost and small vol-

ume per stored bit; disk the advantage of rapid direct

access. These properties—and the scope of the com-

peting optical storage technologies—affect the appli-

cation areas of tape and disk. Tape dominates

archival digital storage, and audio and video mag-

netic recording. Disks—including such developments

as redundant arrays of inexpensive disks (RAID) are

ubiquitous in storage for computers.

2.5 Particulate Recording Media

The original (and long since obsolete) recording me-

dium was a magnetized wire. This was replaced by a

plastic tape or disk coated with a medium consisting

of submicron size magnetic particles in an organic

591

Magnetic Recording Measurements

binder. The commonly used particles are iron oxide or

chromium oxide or a magnetic metal or alloy; they are

too small to sustain domain walls and each particle

therefore is approximately uniformly magnetized. The

particles typically are of elongated shape, giving each

particle a preferential magnetization axis; an alterna-

tive class of particulate media use submicron barium

ferrite platelets that have a very large magnetocrys-

talline anisotropy that aligns their magnetization

along the platelet normal. In all these media the par-

ticles are spatially distributed randomly, and they can

be geometrically oriented during fabrication.

In operation, each magnetized region of a partic-

ulate medium must contain a large enough number of

particles to keep the noise due to number fluctuations

and anisotropy distribution in bounds.

2.6 Film Media

A disadvantage of particulate media is the presence

of the binder which constitutes wasted nonmagnetic

volume, and the difficulty of fabricating media with

magnetic volume fractions exceeding 60–70%. The

disadvantage is overcome by using polycrystalline

oxide, ferrite, and especially metallic alloy films

whose grains can occupy very nearly the entire film

volume. This also means that the medium can effec-

tively be a single layer of grains, thus considerably

thinner than a typical particulate medium. Very thin

media are ideally suited for high-density longitudinal

recording.

A generally undesirable consequence of close pro-

ximity is the resulting exchange coupling of the grains

that leads to magnetic clustering and results in in-

creased noise. Various metallurgical procedures have

been found capable of inducing grain boundary

compositional segregation that reduces the coupling

and improves noise performance.

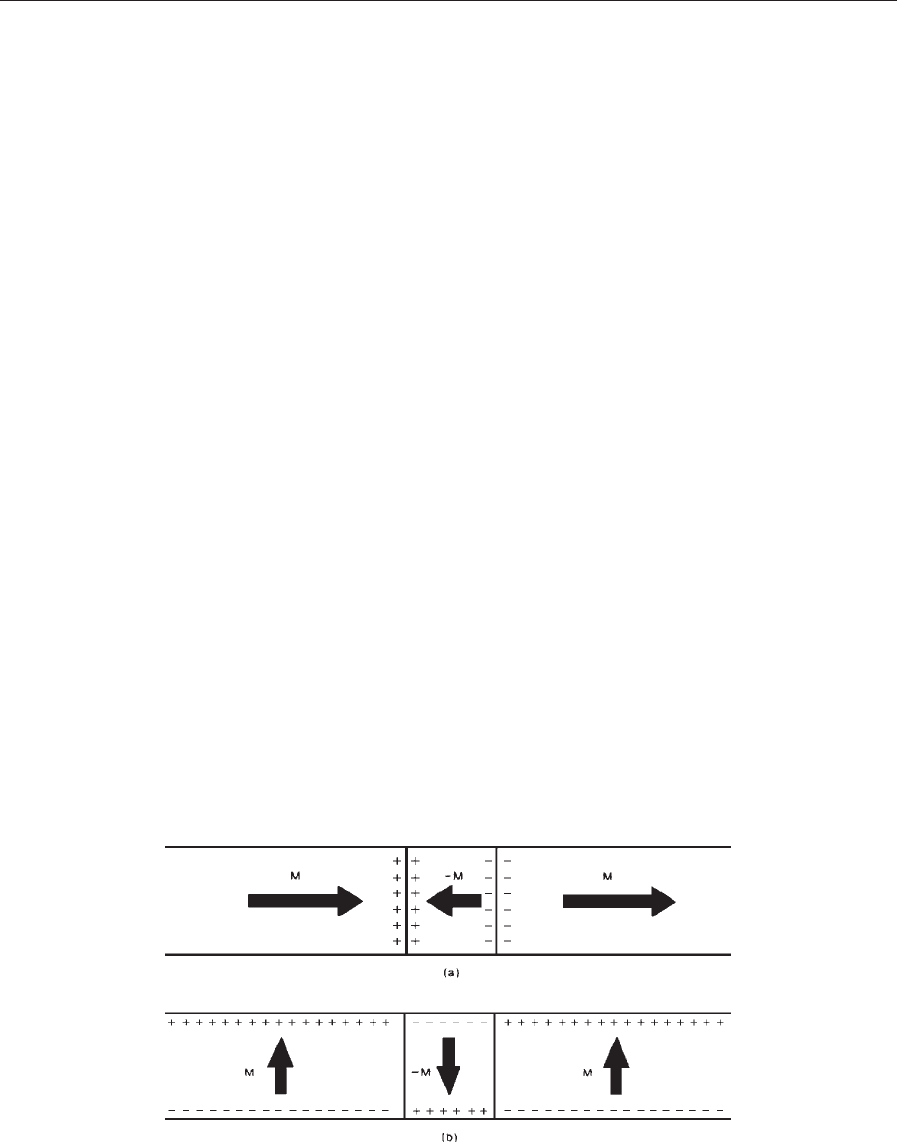

2.7 Longitudinal and Perpendicular Recording

Information is recorded by magnetizing regions of

the recording medium in opposite directions either in

the plane of the planar medium (longitudinal record-

ing) or normal to the plane (perpendicular recording)

(see Fig. 3). The dominant recording technology is

longitudinal, but it has been argued for several dec-

ades that perpendicular recording offers advantages

that will lead to its widespread adoption as recording

densities increase. Longitudinal recording is favored

by circumstances of history and inertia; in-plane

magnetization is favored by shape anisotropy in thin

planar media; longitudinal write heads are simpler;

and the information is stored in the form of magnetic

poles with large fringing fields. This last advantage is

also a central problem of the technology, because the

demagnetizing fields associated with the poles be-

come destabilizing at high recording densities. In

perpendicular recording the magnetization direction

is determined by the chosen magnetocrystalline an-

isotropy of the material. Its greatest advantage is that

oppositely magnetized adjacent regions give rise to

magnetic dipoles instead of poles, and the resulting

demagnetizing fields are stabilizing.

2.8 Keepered Media

Keepered media are films in which a magnetically soft

film (the keeper) is deposited under the recording

medium, on the side opposite the head, or on top of

the recording layer (in which case the recording is

done through the keeper layer) (see Fig. 4). This de-

vice addresses two of the issues raised in Sect. 2.7. In

a longitudinal medium the adjacent soft magnetic

film provides a low reluctance path for the demag-

netizing flux, shunting it out of the medium itself. In a

perpendicular medium it provides a low reluctance

Figure 3

Longitudinal and perpendicular recording schematics (after Mee and Daniel 1990).

592

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

return path for the perpendicular component of the

write head flux, effectively increasing the recording

layer thickness.

3. Medium Me asurements

3.1 Definitions and Measurements

Magnetization M: magnetic moment per unit volume,

a vector quantity of magnitude M.

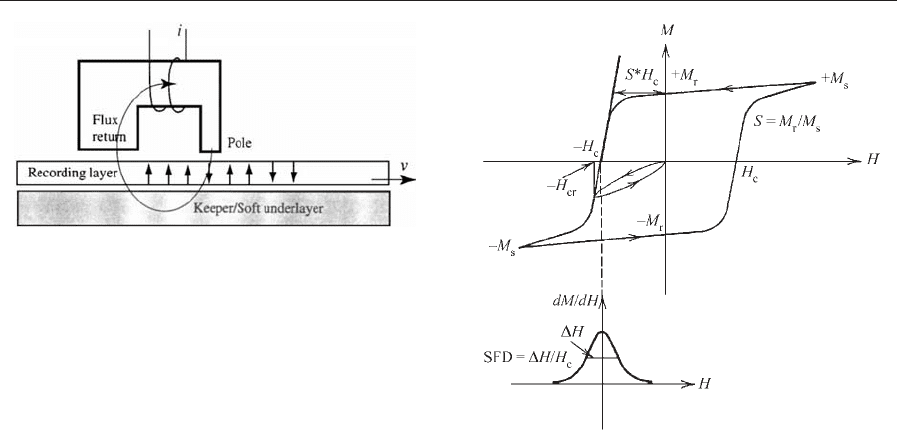

Hysteresis loop: a plot of magnetization M as a

function of magnetic field H (Fig. 5). This is a mul-

tiple-valued function, depending on the sequence in

which the time-varying field is applied. In the figure it

is assumed that the measurement is made starting

from a very large field in either direction.

Saturation magnetization M

s

: strictly, the magnet-

ization of a uniformly magnetized region (domain) in

a homogeneous magnetic medium. This is an intrinsic

property, a function of temperature, and weakly de-

pendent on magnetic field and stress. In practice, M

s

is also used for the magnetization M of any (not

necessarily homogeneous) magnetic material in a

large applied field.

Remanence (or remanent magnetization) M

r

: the

magnetization of a magnetic object that remains after

it has been magnetized in a large applied field that is

subsequently removed. Remanence is an extrinsic

quantity that depends on microstructure, shape, and

the phase of the moon (this last factor is meant to

indicate the experimentalist’s frustration with the

sometimes apparently random fluctuations in the

results of very carefully controlled measurements).

A related quantity most meaningful for magnetic

recording, especially with thin media, is the product

of remanent magnetization and thickness M

r

t. This

quantity determines the magnetic moment associated

with a bit cell of a given size, and thus the ability to

detect it. M

r

t of a specimen of known area can be

accurately measured in a VSM even if M

r

and t are

poorly determined.

Remanence curve M

r

(H): a plot of the sequence of

final values of M reached when a specimen is cycled

as follows: saturation by a large applied field; appli-

cation of a reversing field H which is then reduced to

zero; resaturation; and repetition with a different re-

versing field. On this curve, the remanence as defined

above is M

r

(0).

The remanence curve of a specimen can be meas-

ured directly, for example in a VSM, by following this

procedure, a time-consuming process. A fair approx-

imation can be constructed from the hysteresis loop

by drawing lines, with the slope of the loop at re-

manence, from the loop at several values of reversing

field to the M-axis, and associating with each field

value the value of M at the intersection with the axis.

The remanence curve of a recording medium can

also be measured nondestructively on a spin stand by

measuring the output voltage from nonsaturating

transitions.

Coercivity H

c

: the value of reverse applied mag-

netic field required to reduce the magnetization from

remanence to zero in the presence of the reversing

field.

Remanence coercivity H

cr

: the value of reverse ap-

plied magnetic field required to reduce the magnet-

ization from remanence to zero after the reversing

field has been turned off.

Squareness: a measure of the degree to which the

shape of a hysteresis loop is approximated by a rec-

tangle. Two measures of squareness are in common

use: the remanence squareness S ¼M

r

/M

s

which

measures how close the top and bottom traces of

Figure 4

Perpendicular recording schematic with keepered media

and probe-type head (reproduced by permission of

Academic Press from Magnetic Information Storage

Technology, 1999, p. 193).

Figure 5

Schematic hysteresis loop (after Hoagland and Monson

1991).

593

Magnetic Recording Measurements

the loop are to a horizontal; and the coercive square-

ness S* (see Fig. 5) which measures how close the

tangent to the loop at H

c

is to a vertical.

Anisotropy energy: energy associated with the di-

rection of the vector magnetization M relative to a

given set of axes. The energy is associated with the

shape of the magnet and with its crystal structure. In

an ellipsoidal body the shape anisotropy energy (ex-

trinsic) is minimum when M lies along the longest

principal axis, and higher when it lies along any other

direction (for example, the magnetization of a mag-

netic needle tends to align along the needle, not

across it). The magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy

(intrinsic) K

a

is the energy per unit volume associated

with the direction of M relative to the crystal axes.

For example, in a uniaxial crystal such as cobalt,

K

a

¼Ksin

2

j, where K is the anisotropy constant and

j is the angle relative to the c-axis.

Anisotropy field H

k

: a magnetic field that represents

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy in the form

K

a

¼M H

k

. In a uniaxial crystal, the magnitude

of H

k

is (2K/M

s

)sin 2j.

Magnetostriction: the deformation of a magnetic

specimen when its magnetization M is varied and,

conversely, the effect of a strain on M. The exchange

and dipolar interaction energy of the atomic magnets

on a crystal lattice depends on their orientation and

on the bond lengths and bond angles. This energy can

be represented as a magnetoelastic constant, an in-

trinsic property of the material, times the product of

the strain tensor and the direction cosines of M. The

equilibrium orientation and strain minimize the

sum of the magnetoelastic energy, which is linear,

and the elastic energy, which is quadratic in the strain

(see also Magnetoelastic Phenomena).

Magnetic viscosity S: a measure of the thermally

activated decay rate of the magnetization M.Itis

found experimentally that the magnetization of a

magnetized body decays logarithmically over a wide

range of time: M(t) ¼M(0)–S logt. This behavior has

been accounted for as being a summation of expo-

nential Arrhenius type decays over a typical range of

energy barriers. The viscosity S is a property of the

magnetic material that is a function of temperature

and of the applied reversing field and it is generally

maximum when the reversing field is equal to the

coercivity (see Magnetic Viscosity).

Grain size and size distribution: the most widely

used media in rigid disk recording are polycrystal-

line films thin enough to consist of a single layer of

grains. Individual grains of these films are too small

to support magnetic domain walls, and therefore are

approximately homogeneously magnetized. Measure-

ments of grain size can use transmission or scanning

electron microscopy. The distribution of grain sizes

can affect the switching field distribution and the

thermal stability.

Intergranular interactions, Henkel plots, and dM:

the grain size sets the ultimate limit on the switching

unit and hence on storage density. However, intergra-

nular interactions can couple the switching behavior

of neighboring grains, and contribute to medium

noise. Intergranular exchange coupling can lead to

the formation of grain clusters; dipolar interactions

can favor parallelism (in longitudinal media) and

antiparallelism (in perpendicular media) of neighbor-

ing grains.

A measure of intergranular coupling can be ob-

tained by the use of a Henkel plot or the equivalent

dM curve. The Henkel plot is generated by obtaining

a curve named the isothermal remanent magnetiza-

tion M

ri

(H). This curve is measured by the same

procedure as M

r

(H) described above (in this context

sometimes denoted M

rd

(H)), except now the starting

point of each cycle is a.c. demagnetization, with

M

ri

(0) ¼0. It is easy to see that now, since initially

half the switching units are already in the direction

favored by the reversing field, only half as many will

reverse with each field step. Thus one expects that

M

rd

(H) ¼M

ri

(N)–2M

ri

(H). This relation, however,

only holds for non-interacting switching units, and

deviations indicate the presence of intergranular

coupling. The conventional form of representing

the deviations is the Henkel plot, M

rd

(H)/M

ri

(N) ¼

1–2M

ri

(H)/M

ri

(N) þdM(H), with dM positive for

interactions favoring parallelism, negative for anti-

parallelism.

The measurement can be carried out on a coupon

of the medium in a VSM, or nondestructively on a

spin stand by measuring the output voltages from

transitions written on the medium in saturated and

a.c. demagnetized states.

Switching field distribution (SFD): the fraction of

medium magnetization reversed per increment of re-

versing field range dM/dH. This is a function of H,

peaking at or near H

c

. SFD is also sometimes defined

as the reversing field range required to reduce

the magnetization of an initially saturated medium

from M

r

/2 to M

r

/2. SFD can be inferred from the

remanence curve. It has also been measured by

differencing MFM images and counting switching

events.

Time dependence of measurements: the result of a

measurement may depend on the time scale on which

the measurement is carried out. The hysteresis loop of

a specimen is usually measured on a VSM, on a time

scale of minutes or hours, or on a B–H loop tracer,

on a time scale of typically tens of milliseconds.

Magnetization reversals in writing recording transi-

tions take place in nanoseconds. As mentioned ear-

lier, the medium response to a magnetic field is

not instantaneous. Specifically, the coercivity of a

medium depends on the time scale of the measure-

ment, leading to the concept of a dynamic coercivity,

which increases with the rate of field application. A

phenomenological theory has been developed which

is quite successful in accounting for such effects

(Sharrock and Flanders 1990).

594

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

Orientation ratio: it is desirable in several media to

have the magnetic properties along the track different

from those across the track. For tape, the coercivity

along the tape can be greater than that across it and

for disks, the circumferential (recording direction)

coercivity may be larger that the radial coercivity by

tens of percent. This phenomenon is built into the

material at the time of manufacture and can be con-

trolled by the deposition conditions, especially angle

of incidence and applied magnetic fields, or from an-

isotropy in the substrate, especially microscratching.

The conventional measure of this is the ratio of the

macroscopically measured recording to cross-track

coercivities.

3.2 Head Measurements

The write head must generate enough flux to saturate

the recording medium and must be able to operate at

high enough frequency and/or with fast enough pulse

response to satisfy the system requirements, and it

must do these things with reasonable head efficiency

and at low cost.

The earliest write heads were small electromagnets

with high permeability ferromagnetic metal cores.

They were satisfactory for low-frequency applica-

tions. The frequency response is limited by eddy cur-

rent effects, which can be reduced by laminating the

cores and pole pieces. This makes metal heads usable

at high audio frequencies. Better performance at

megahertz frequencies could be obtained by using

high-resistivity ferrite cores. This sacrificed permea-

bility and flux density for frequency and pulse re-

sponse, but was satisfactory for writing on recording

media whose coercivity was no higher than about a

third of the ferrite’s saturation magnetization, in the

range of 1000 Oe. Ferrite heads continue to be used in

video recording; these are typically single crystal

structures fabricated by precision grinding, a rela-

tively costly procedure.

Write heads for modern high-coercivity media are

again fabricated from ferromagnetic metals and al-

loys, now in the form of high-moment, high-resistiv-

ity films thin enough to be resistant to eddy current

losses. These heads, and the coils driving them, are

fabricated as integrated structures by lithographic,

deposition, and etching techniques similar to those

used in the fabrication of integrated semiconductor

circuits.

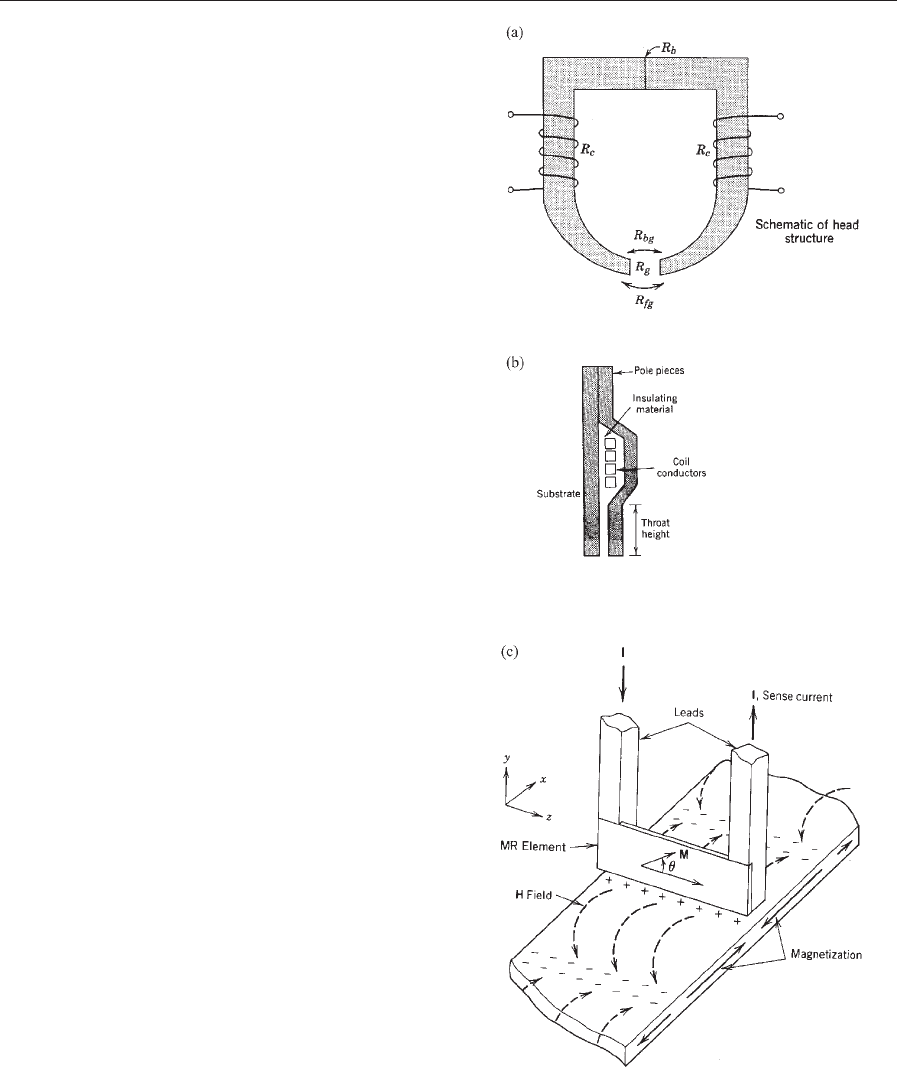

3.3 Write Head Fields

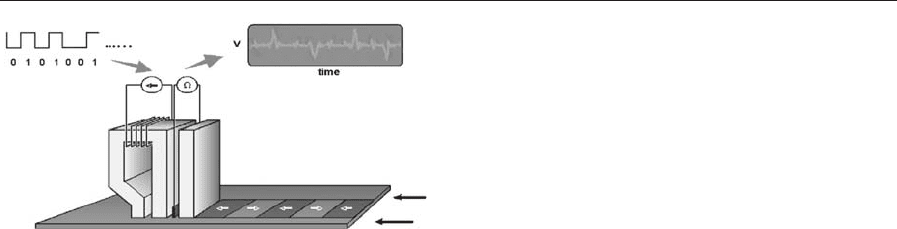

Most recording heads are inductive in nature: a soft

ferromagnetic core is coupled to a conductive write

coil (Figs. 6, 7). The current in the coil creates flux

that flows through the magnetic pole pieces. Some of

the flux squirts out of a gap in the magnetic circuit.

This flux is used to magnetize regions of the magnetic

Figure 6

Recording head schematics: (a) ring-type head, (b) thin

film-type head cross-section, (c) magnetoresistive (MR)

head.

595

Magnetic Recording Measurements

medium. The magnetic flux must be of sufficient

strength to bring the magnetization to M

r

. This field

is typically much larger than the coercivity. A good

rule of thumb is to supply a field about three to five

times the medium’s macroscopically quasistatically

measured coercivity. To supply this large a field re-

quires pole materials to have a very large effective

permeability and saturation magnetization.

The pole piece saturation magnetization can be

measured macroscopically in a variety of ways: VSM,

a.c. hysteresis looper, etc. The effectiveness of the

write field is verified easily through the satura-

tion plot (see Sect. 4). The curve should reach and

hold a maximum output, or even decrease slightly

due to overwriting, for large currents. This indicates

either that the medium is saturating or that the head

pole material is saturating. If the head can write on

higher coercivity media then saturation of the medi-

um is differentiated from head saturation. Satura-

tion of the pole material usually occurs first at the

pole piece corners and where the coil couples with

the poles. Once saturation is approached, the flux

enhancement from the material’s permeability is

diminished.

The fabricated pole pieces typically have multi-

domain structure. These domain structures can affect

the writing process through speed, stability, and ef-

ficiency. Domains usually rotate faster than domain

walls can move, so in multi-domain heads for high-

speed applications it is desirable to have the walls

pinned compelling the magnetization to rotate in

response to applied fields. Domain wall jumps induce

noise into the readback channel, even microseconds

after writing. The direction and number of the

domains also control the flux guiding property of

the core.

The geometry of the writing field is controlled in

large part by the geometry of the head pole pieces.

The gap length controls the depth of the recording (of

importance to particulate media but not for film me-

dia), the angle at which the medium sees the field, and

the writing efficiency of the structure. During record-

ing, the gradient of the write field is one of the most

important metrics in defining good, sharply written

transitions. Optimal head design attempts to have the

maximum of the field gradient occur where the field

equals the medium coercivity, which is where the

transition is written. In addition, the gap defines

the side writing; the field that fringes from the side,

creating an effective erase band but potentially eras-

ing previously written data.

The recording head in a rigid disk or high-end tape

drive may be asked to switch at nanosecond rates to

accommodate data transfer rates of hundreds of

megabytes per second. As with media measurements

(especially the dynamic coercivity) the high-frequency

character of the switching of magnetization in mag-

netic head structures is critical to the success of the

operation of the head. a.c. hysteresis looper meas-

urements and conventional permeameters are not

able to operate in the gigahertz range. The measure-

ments of materials for use in heads are typically done

with a pulsed frequency measurement. One method

involves discharging a charged capacitive structure

into a narrow stripline. The current through the line

induces a magnetic field around it. The presence of a

magnetic material will change the impedance of the

pulsed stripline structure. Pulses can produce subna-

nosecond fields and reach fractions of a tesla. So-

phisticated recording measurements can be carried

out that can separate the write field rise time effects

from other system effects.

An increasing number of read transducers are not

inductive but flux-based sensors. The phenomenon

used most often is magnetoresistivity. The material’s

magnetoresistance ratio, DR/R, and the anisotropy,

H

k

, control the sensitivity and ultimately the figure of

merit of these transducers.

These properties may be measured on the bulk

films or in the patterned sensors as described above.

Domain structures, demagnetizing fields, and stresses

can have a tremendous effect on ultimate device

performance so it is most meaningful, but usually

more difficult, to measure the properties of the trans-

ducer itself.

An important issue with system performance of

these devices is stability. The write field can affect the

read transducer by changing the nominal state of the

films and can induce noise through changing domain

states of the write head long after the write current

has ceased. A biasing field, from currents or magnetic

materials, is used to assist in creating a known initial

state and linearizing the output. The bias design point

can be inferred from the magnetoresistance transfer

character measured as described previously.

The read gap, the effective separation between

the shields, is the dominant factor that controls

the spatial resolution of a read head and, hence, its

high-frequency performance. The physical gap is usu-

ally about 10% shorter than the gap inferred from

magnetic recording measurements. Magnetically

inactive inner surfaces account for this increase in

effective gap.

Figure 7

Recording schematic.

596

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

The read width is largely controlled by the separa-

tion between the conductive leads, although some

devices exhibit sensitivity to flux from the side,

known as side reading. In general, a write-wide/read-

narrow configuration is desired for overall device

performance. This relaxes the tolerance for servoing

during a read operation, but trades off some signal

output.

Flying height, the distance between the head and

the medium, is important to system performance

since the output decreases exponentially with this

separation. For rigid media, the head is designed with

an air bearing to fly over the medium. The flying

height may be measured optically, using a transpar-

ent head. As the separations are nominally less than

the wavelength of visible light, broadband white light

interferometry is used for this determination. Capac-

itive measurement can also provide the flying height

if the medium is conductive and the head has some

conductive contact area. Since the output varies ex-

ponentially, recording measurements can be made to

infer the flying height as well. In most tape systems,

contact between the head and medium is assumed but

it is experimentally found that high-velocity tape

drives have nonzero head–medium separations.

4. Recording Measurements

4.1 Introduction

The measurements discussed above concern proper-

ties and parameters that affect the performance of

the recording system, and that are measured using

a variety of instrumentation. Some parameters that

impact performance are significant only in the con-

text of recording, and can be carried out only in the

recording system itself, on a spin stand or using

the disk or tape drive itself. This section describes

such measurements.

4.2 Saturation Plot

The measurement of the recording output (voltage

amplitude) as a function of write current is the sat-

uration plot. Initially the medium is demagnetized or

in uniform remanence (from d.c. saturation). The re-

cording head is used to apply the magnetic fields. The

spatial field gradients are enormous and have a huge

impact on the resulting magnetization in the medium.

Very small amplitude applied fields will have no effect

on whatever state the medium is in. As the applied

field is increased through application of larger cur-

rents, more and more of the medium will respond, in

part through the SFD. If a square wave signal is ap-

plied to the head as it moves relative to the medium,

the magnetization will approximate this square wave

remanence

4.3 Density Plot or Rolloff Curve

The rolloff curve is a measurement of the recording

(voltage amplitude) output as a function of the re-

cording density. For longitudinal recording, low den-

sities have larger output amplitude than the higher

densities. This is a consequence of demagnetizing ef-

fects and of the finite gap length. The internal de-

magnetizing field stresses the remanent magnetization

for these densities more than in low-density record-

ings. This spreads transitions and reduces the mag-

netization, causing a reduction in the sensed output.

The finite gap length also affects the output as a

function of recording density. It was shown (Wallace

1951) that the output of a single-frequency sinusoidal

recording varies as a sine function of density, with the

ratio of wavelength to read head gap length as the

argument of the sine. For digital recording, the out-

put tracks this phenomenon as the fundamental of

the square wave recorded signal. The nulls in the sine

function (‘‘gap-nulls’’) correspond to an even number

of transitions filling the length of the gap. D

70

or D

50

,

the density before the first gap null at which the

readback output is 70% or 50% of the low density

output, are typical design values for the maximum

density in a system.

4.4 Read Head Linearity, Asymmetry, and

Baseline Shift

Read head output, in particular MR transducers, are

characterized by their linearity and asymmetry as well

as their down-track and across-track spatial resolu-

tion. The head may respond differently to upward

flux from a positive magnetic transition than from

downward flux arising from a negative transition

(asymmetry). The output may also not respond lin-

early to applied flux—a stronger flux may not pro-

duce a proportionately larger output. In addition, the

level the output may reach after sensing a positive

transition may be different from the level seen after a

negative transition (baseline shift). These asymmetric

and nonlinear effects may challenge the channel

demodulation and degrade system BER (bit error

rate, the fraction—before any error correction—of a

misread zero or one) and performance.

4.5 Noise Spectrum

One measurement of the background system per-

turbations is the averaged noise power. This meas-

urement may be taken with a spectrum analyzer

providing measure of the noise power over a wide

band of frequencies. The measurement can be made

with the medium in d.c. remanence, a.c. demagnet-

ized, or written with a very high-frequency signal

that may approximate a.c. erasure. Note that this

597

Magnetic Recording Measurements

measurement does not account for any signal

dependence of the noise.

4.6 Signal-to-noise Ratio

There are different ways of measuring a recording

system’s overall ability to reconstruct the written sig-

nal. In general, the system’s ability to reproduce the

written signal is proportional to the signal’s ampli-

tude with respect to the system’s noise. It is assumed

that the noise is independent of the signal and uni-

form over a broad frequency band (white Gaussian

noise). A typical measurement of this metric is to

record a single, moderate-valued frequency onto the

medium, measure the signal’s amplitude, and com-

pare this output to the broadband noise. This noise

may be measured from a medium that may have been

erased with an a.c. or d.c. field, or may be written

with a density beyond that which the system can re-

produce. In a system characterized by Gaussian

noise, the performance in detecting a signal is deter-

mined by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Thus, the

raw bit error rate is then determined by the SNR.

4.7 NLTS

When the transitions close in on one another their

signal pulses begin also to overlap and interact,

changing their perceived shape. For moderate re-

cording densities, the pulses can be represented as the

linear superposition of two independent pulses. Such

linear phenomena are usually easy to characterize

and can be effectively removed through pre- and

post-compensation techniques. As the transitions

move closer together, their output can no longer be

represented as the linear superposition of independ-

ent pulses. This phenomenon, usually referred to as

nonlinear transition shift (NLTS), may be due to

magnetic interactions of one transition with another

and erasure of the magnetization between the tran-

sitions, and may be caused by a combination of the

writing process of the transitions and of effects after

the transitions have been written. The measurement

of this effect can be done in several ways: writing

and reading series of di-bits, using a pseudo-random

binary sequence, or measuring noise as a function of

recording density of a single tone.

4.8 Track Profile and Bathtub

The ability to recover data is sensitive to the system’s

ability to remain on the data track during the time the

transducer is reading the data. The measurement of

track misalignment or track misregistration (TMR) is

ever more challenging as the tracks become narrower.

From a system viewpoint, the percentage of error

allowed for TMR remains relatively constant. In

general the head is not constantly being kept on track

but servoed intermittently for a short time and then

allowed to run freely. The track profile is generally

plotted as the track averaged output amplitude as a

function of the distance off track. If the source for the

read signal were a very narrow track the curve would

trace out the read sensitivity function of the head:

insensitive to signals far off to either side; increas-

ing as the source comes closer to the head; and uni-

form as the source moves across the read head’s

width (provided that the sensor’s configuration is

symmetric).

Such a ‘‘micro-track’’ can be approximated by

writing a full width track and erasing all but a very

narrow region of the track. If the bit error rate is

measured and plotted as a function of distance off

track, the error would increase as the head moves

from the track center. When plotted with the vertical

axis as the log of the BER and the abscissa as a linear

function off-track, the resulting curve resembles a

bathtub. The base of this curve with the lowest BER

(lowest probability of error) will be relatively flat

for a small distance and rise along the edges as the

read transducer moves further from the track center.

The upper edge of the curve (bathtub edge) will be

reached when the signal can no longer be determined,

when the read head is completely off the written track

(and cannot even read the signals from its edge).

The measured track profile includes both the read

sensitivity and its width as well as the write head’s

write width. Typical head configurations using a

magnetoresistive head for read along with an induc-

tive writer are designed so that the written track is

wider than the reader’s sense width. This ‘‘write-wide/

read-narrow’’ configuration trades off some read sig-

nal (since not all of the written magnetization’s flux

enters the head) for more robust tracking—the head

can wander from the track-center and still be reading

over the original track.

4.9 Squeeze and 747

These measurements are aimed at measuring the sys-

tem’s ability to reproduce recorded data in the pres-

ence of other information in adjacent tracks. After a

test track has been written, adjacent tracks are writ-

ten on both sides of the test track. The head is re-

turned to the test rack center and the original data are

read. Squeeze is measured as the adjacent tracks are

moved in from afar. Initially the tracks have no ef-

fect, but will increasingly perturb the readback signal

as they are brought in contact with the test track and

then overwrite it. Eventually the test track will not be

recoverable. This curve has a form something like the

right side of a v-shaped valley. Due to the symmet-

rical approach from both sides of the over-writing

tracks, it makes sense to plot only positive values.

In a more elaborate and more closely recording-

like test, old information data tracks are first laid

598

Magnetic Reco rding Measurements

down so that they extend (beyond, underneath) to the

right and left of the test track (which overwrites a

portion of the old information tracks). This is the

worst-case situation for direct overwriting. The ‘‘747-

curve’’ is formed as this situation is further aggra-

vated by squeezing overwritten tracks into this

situation and the original signal is measured with

the head moved back on-track. Initially, when the

squeeze tracks are far from the test track, no changes

in the output are observed. When the squeeze tracks

approach the test track, just enough so the edge of the

head’s erase band erases the old information but does

NOT erase any part of the test track, the test signal

becomes easier to read since all of the old information

has been erased and the newly written signal is

at least an erase-band’s distance away. The system’s

off-track capability (OTC), or track misregistration

(TMR) allowed to obtain a fixed BER increases

slightly, proportional to the erase band of the write

head. As the tracks squeeze in further, they begin

to overwrite the test track reducing the OTC. These

data, when plotted, modify the v-shaped valley as

seen with a simple squeeze test by adding a mound to

the top edge of the valley. This shape resembles the

side view of a Boeing 747 aircraft: the nose rises to the

hump of the cockpit that rolls off and levels out well

above nose-level.

4.10 Write Width, Read Width, Side Reading,

Side Writing

The physical, patterned dimensions of the head are

usually not equal to the precise read and write widths

as determined using recording measurements. The

effects of all of these parameters are seen in any usual

recording system. The read and write widths are

typically wider than those measured optically. Most

write elements produce fields along the edge of the

head that tend to degrade or erase old information a

fraction of a gap length. This effect may provide a

system with a natural guardband. Likewise the reader

senses flux arising from beyond the side of the head.

4.11 Pulse Shape

The shape of the voltage output is the product of the

read head sensitivity function and the fringing mag-

netic field. The medium’s magnetization controls only

a part of the output pulse shape and the head’s spa-

tial extent determines the rest. The write field gradi-

ent, the medium’s switching field distribution, and the

demagnetizing fields at the transitions determine the

sharpness of the magnetization through the transition

and hence the spatial distribution of the external flux.

The read head gap and the flying height define the

spatial sensitivity of the sensor, analogous to the de-

termination of spot size and resolution by the aper-

ture in a classical optical system. The pulse shape in

space determines the resolvability of a signal consist-

ing of a set of pulses arising from closely spaced

magnetic transitions. If the pulse is broad, the pulses

will need to be spaced farther apart if the system is

to recover the signal, as compared to a pulse whose

amplitude is the same but whose width is narrower.

The measurement of an isolated pulse’s width is usu-

ally denoted by the width at half the amplitude height

and designated as PW

50

.

4.12 Jitter

The most critical effect in determining a digital,

saturation recording system’s ability to recover infor-

mation is the timing of the transitions. The mis-

placement of this timing is jitter. If the transitions

could be placed and sensed with unlimited precision,

the amount of information stored would be bound-

less. In real systems, a fraction of the bit cell, denoted

as the timing window, is the interval when the tran-

sitions are allowed to occur in order to be counted. If

a transition falls outside of this window a raw error

will occur. The timing errors can come from elec-

tronics noise, magnetic noise in the head, or from the

magnetic medium (in particular its microstructure),

and can manifest itself during writing, reading, and in

general both. A jitter measurement quantifies the

statistics of this uncertainty. A simple measurement

consists of writing a single frequency square wave

onto the medium and building up the histogram of

the timing errors of the readback signal.

4.13 Thermal Decay

As areal recording densities steadily increase the size

of the bit cells decrease proportionately. In order that

the shrinking bit cells may contain sufficient grains to

supply reasonable statistics, so that written signals

can be easily recovered (conventionally at least hun-

dreds of grains), grain size must shrink to accommo-

date these needs. The stability of the grain is a

function of the volume of the grain. Thermal energy

becomes comparable to the magnetic stabilization

energy with grain sizes near the regime where the

atoms are readily countable, roughly 100 A

˚

on a side.

In this superparamagnetic regime, the grain remains

magnetized but the direction of its magnetization is

changed by thermal agitation. In a recording system,

this change in magnetization direction results in deg-

radation of a recorded signal. Since this is a thermal

effect, time as well as temperature is a determining

factor of the amount of signal lost. Assuming

Arrhenius behavior, an assembly of non-interacting

particles, each having the same activation energy,

displays an exponential decay of magnetization with

time. A collection of non-interacting particles with

a wide, uniform distribution of activation energies

exhibits logarithmic time decay. Many conventional

599

Magnetic Recording Measurements