Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced

(Order to Order)

This article is concerned with high magnetic field

magnetization processes in ferrimagnets which are

connected to the variation of mutual orientation of

their magnetic sublattices and which reveal them-

selves through characteristic kinks and jumps in the

magnetization curves. The magnetic symmetry of a

crystal changes when the orientation of the magnetic

sublattices spontaneously varies. In other words, a

phase transition accompanied by a change of the

magnetic symmetry takes place. In the present ter-

minology such phase transitions are referred to as

field-induced phase transitions (FIPTs), which may

be of first or second order. It is evident that such

phase transitions are accompanied by anomalous be-

havior of some physical properties and characteristics

of the ferrimagnets (susceptibility, thermal properties,

magnetostriction, magnetoelastic anomalies, Hall

effect and magnetoresistance, magneto-optic pheno-

mena, etc.). Comprehensive data and bibliography

have been detailed in the survey of Zvezdin (1995).

FIPTs are traditional subjects in the physics of

magnetic phenomena. The first examples attracting

considerable attention were spin-flop transitions. The

concept of these transitions was proposed by Ne

´

el in

1936, and they were found later in CuCl

2

H

2

Oby

Poulis and co-workers in 1951. In these transitions a

collinear phase turns into a canted phase and further

into a ferromagnetic one in an increasing field. A

distinctive feature of the spin-flop transition in an

ideal Ne

´

el antiferromagnet is that the differential

susceptibility of the material in the angular phase is

not dependent on the magnetic field or temperature.

Later, similar phase transitions were investigated in

ferrimagnets whose behavior turned out to be more

sophisticated and interesting. The latter materials

form typical examples to illustrate the general fea-

tures of FIPTs.

That noncollinear magnetic structures may exist

was first demonstrated theoretically by Tyablikov in

1956. He also defined the conditions of their existence

in the case of isotropic ferrimagnets and calculated

anomalies of the magnetization arising in the vicinity

of such transitions. Perhaps the first experimental

manifestations of these phenomena were observed in

rare earth iron garnets by Rode and Vedyaev in 1963.

1. Magnetic Materials and H–T Diagrams

To comprehend FIPTs in a ferrimagnet and to ob-

tain its phase diagrams, it is of prime importance to

take the real magnetic anisotropy of the material into

account. Consequently, various interesting phase dia-

grams result for ferrimagnets close to the compen-

sation temperature. They include lines of first- and

second-order phase transitions, critical points of

the liquid–vapor type, and tricritical points, where

the first-order phase transition line goes over to the

second-order one on the line separating the phases,

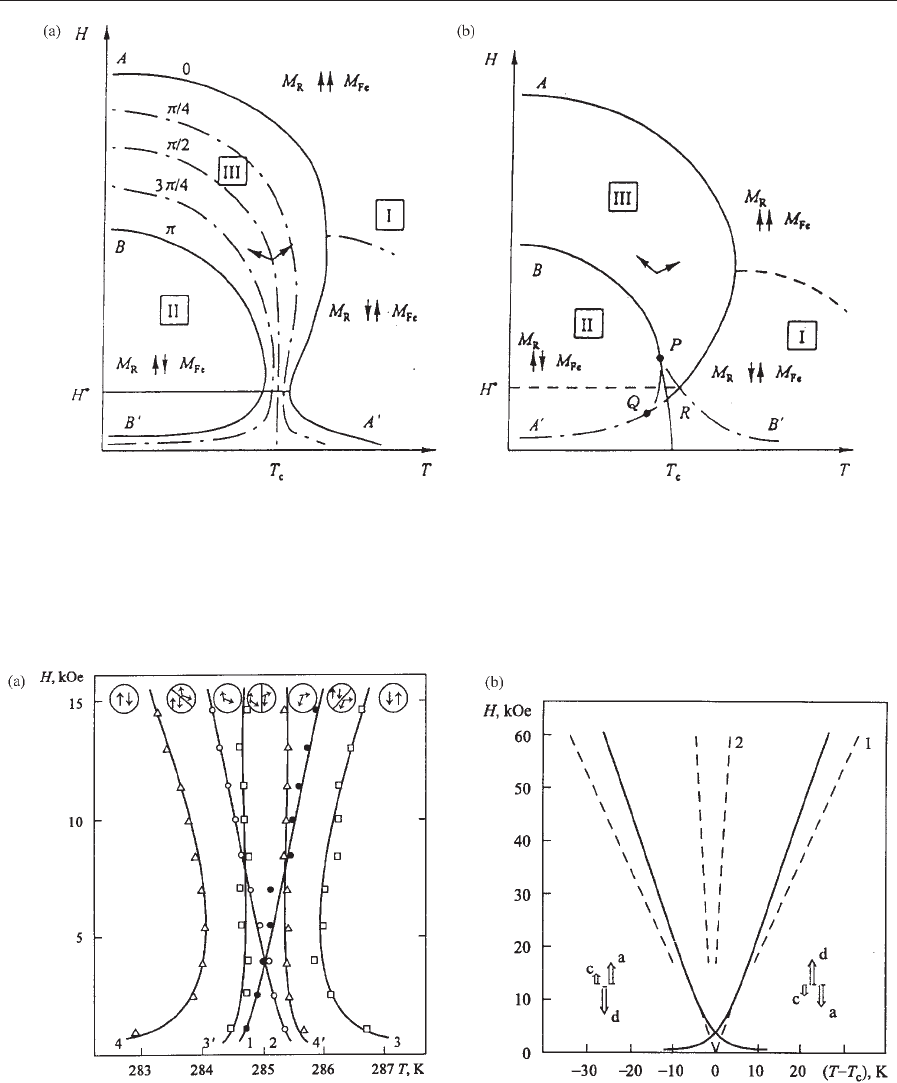

etc. (e.g., see Fig. 1).

1.1 Rare Earth Ferrite Garnets

FIPTs have been investigated rather closely in rare

earth ferrite garnets where the critical fields of the

transitions into the canted phase are not too large.

Gadolinium iron garnet has been studied in much

detail owing to the fact that application of the Ne

´

el

model is well justified since the Gd

3 þ

ion, whose

ground state is an orbital singlet

8

S, has a compar-

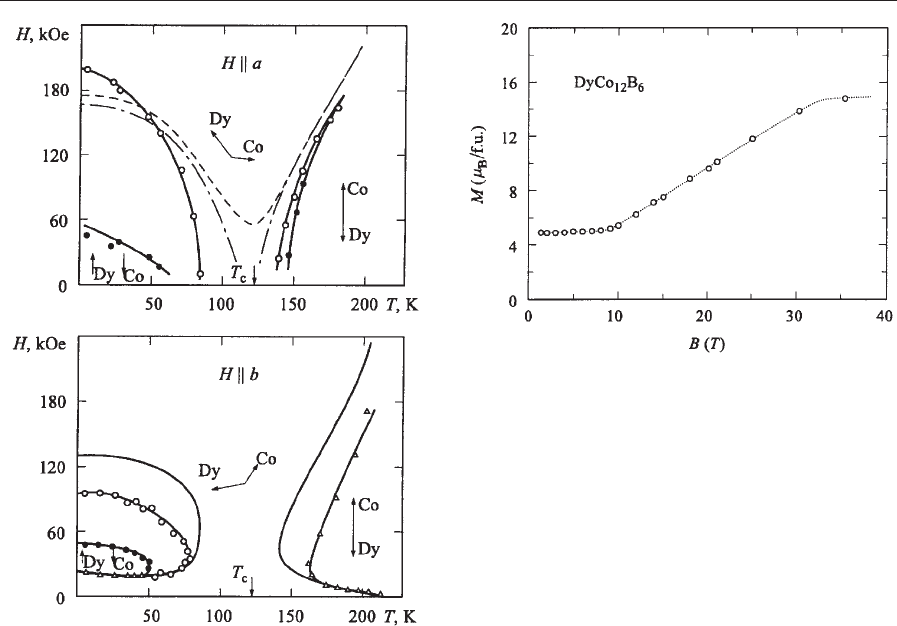

atively small magnetic anisotropy (Fig. 2). The rare-

earth sublattices in other rare earth ferrite garnets

possess substantial magnetic anisotropy. The phase

diagrams and the character of the phase transitions

differ essentially from those of Ne

´

el ferrimagnets.

1.2 Intermetallic Compounds

Considerable attention has been devoted to interme-

tallic compounds R–TM, where R ¼rare earth and

TM ¼transition metal (e.g., RCo

5

,R

2

Fe

17

,R

2

Co

17

,

R

2

Fe

14

B, RFe

2

etc.) (see Alloys of 4f(R) and 3d(T)

Elements: Magnetism) (Fig. 3).

One of the various interesting phenomena inherent

in these materials is the FIPT. Polycrystalline and

powder samples have been the main objects for

measurements. With the progress in both single-crys-

tal growth and strong magnetic field production,

crystal field effects and the role of magnetic aniso-

tropy have become obviously of particular interest.

1.3 Free-powder Samples

Single crystals are not always available for the study

of FIPTs and intrinsic magnetic properties. Free-

powder samples are a good alternative. Verhoef et al .

(1989, 1990a, 1990b) and de Boer and Buschow

(1992) reported the elegant high-field free-powder

method, which has been used to determine the inter-

sublattice coupling strength in a fairly large number

of intermetallic compounds. The particles of the free-

powder sample, having a size of about 40 mm, are

assumed to be small enough to be regarded as single

crystalline and are free to rotate in the sample holder

during the magnetization process, so that they will

be oriented by the applied field with their magnetic

moment in the field direction.

Verhoef et al. (1989) analyzed magnetization

curves of Er

2

Fe

14–x

Mn

x

C compounds. These mag-

netization curves are the same as in the isotropic case.

Only if both sublattices display magnetic aniso-

tropy can an influence on the free-powder magneti-

zation be observed. Figure 4 shows the free-powder

520

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

Figure 2

(a) Phase diagram of gadolinium ferrite garnet for H

-

c [111] (Kharchenko et al. 1975a) and (b) the

‘‘reconstructed’’ high-field phase diagram of the epitaxial film Y

2.6

Gd

0.4

Fe

3.9

Ga

1.1

O

12

with T

c

¼183 K (Gnatchenko

et al. 1977).

Figure 1

Phase diagram of a uniaxial ferrimagnet in a field (a) perpendicular and (b) parallel to the easy axis. In (a) the dashed

curves are isoclines y ¼y(H,T). The solid curves pertain to second-order phase transitions. In (b) BP and AR are

curves of the second kind of phase transition, and A

0

R and PB

0

are curves representing the loss of the collinear phase

stability. PQ is a curve representing the loss of metastable canted phase stability, PRT

c

is a curve describing the first

kind of phase transition, and P is the tricritical point (Zvezdin and Matveev 1972).

521

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

magnetization for DyCo

12

B

6

at 4.2 K. This is a good

example of the complete bending process in a ferro-

magnet. The magnetization curve in the canted phase

is nearly linear indicating that the dysprosium sub-

lattice anisotropy is much larger than that of the

cobalt sublattice. It is seen that the effect of the mag-

netic anisotropy of the cobalt sublattice is rather small.

2. Some General Features of FIPTs

The phase transitions considered above are typical

transitions with a magnetic symmetry change. For

instance, during the I–III transition (Fig. 1) the sym-

metry is relative to a rotation around the z-axis (i.e.,

parallel to the external magnetic field) with an angle p

(symmetry element C

z

2

). This symmetry element is

absent in phase III but double the number of equi-

librium states in comparison with phase I are present

here, which are transferred from one to the other by

the ‘‘broken’’ symmetry element. Identical values of

the free energy (‘‘degeneration’’) correspond to these

two states. It is accompanied by a division of the

sample into domains of a low-symmetry phase.

There are peculiarities in the behavior of many

physical properties near the transition point:

(i) The susceptibility goes to infinity. In this case

the susceptibility describes the response of an order

parameter to the thermodynamically conjugated

field.

(ii) The occurrence of anomalies of thermody-

namic quantities such as kinks, jumps, and l-curves

(the specific heat, magnetocaloric effect, Young’s

modulus and sound velocity, magnetostriction, and

magnetooptical phenomena).

(iii) The conversion of the order parameter oscil-

lation frequency to zero (soft mode) and the hinder-

ing of its relaxation.

(iv) The increasing order parameter fluctuations

and their correlation radius.

(v) The expansion of domain walls and the rear-

rangement of domain structure in the sample.

Many theoretical studies devoted to FIPTs have

been carried out using the mean field theory (or using

equivalent approximations such as the Landau

theory). These theories when constructing the free

Figure 4

Free-powder magnetization curves of DyCo

12

B

6

measured at 4.2 K. The circles represent measurements

in a quasi-continuous field and the dotted lines represent

a measurement in a field varying linearly with time

(Zhou et al. 1992a).

Figure 3

Experimental and theoretical phase diagrams of

DyCo

5.3

in a field directed along the easy axis a and

along the hard axis b in the basal plane: J, experimental

critical field (H

0

cr

) and anisotropy field during increase of

the external field;

, critical field (H

00

cr

) during decrease

of the external field;o,critical fields coincide. The heavy

lines are experimental phase diagrams, the thin solid

lines are theoretical lines of phase transitions of the

second kind, the dotted lines are theoretical stability

curves of the collinear phase, and the dashed–dotted

curves those of the noncollinear (high-field) phase

(Berezin et al. 1980).

522

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

energy of a system neglect, to some extent, the fluc-

tuations of the order parameter. In the region of

the transition temperature, i.e., in the region where

the system stability is lost, the fluctuations increase

strongly and these theories become inapplicable. A

characteristic feature of the phase transitions studied

is the fact that the Landau theory can be used for

their description with practically no limitations. The

region of inapplicability becomes extremely narrow:

DT E10

6

–10

8

K. This is a consequence of the

fact that the fluctuations that occur in the region of

the transition have a very large value of correlation

radius.

3. Physical Anomalies Near FIPTs

3.1 Magnetization and Susceptibility

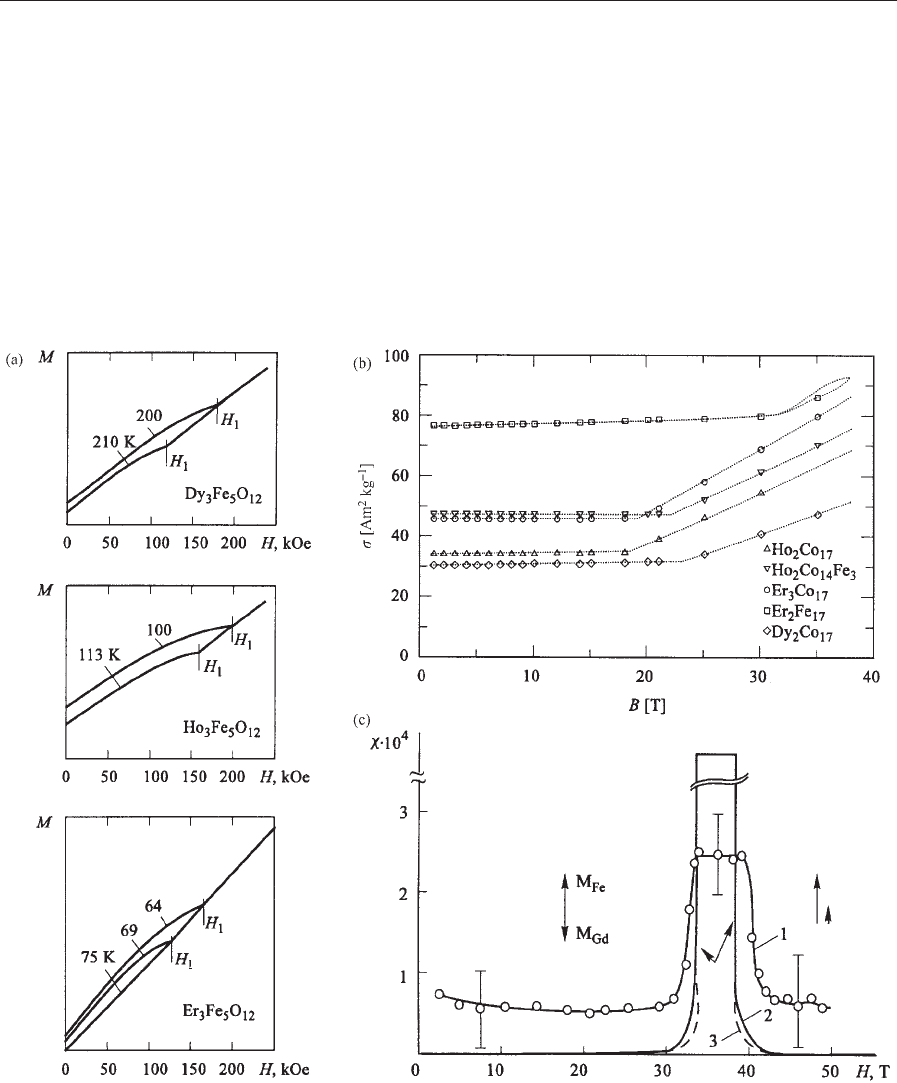

The magnetization isotherms M

T

(H) show a kink

and the longitudinal susceptibility shows a jump

at the transition into a noncollinear phase. This fact

can be employed for the experimental determination

of the critical fields. The field dependence of the

magnetization in ferrite garnets of dysprosium, hol-

mium, and erbium is shown in Fig. 5(a). The linear

parts of M

T

(H) describe the magnetization in the

collinear phase and the curved parts describe the

Figure 5

Field dependences of (a) the magnetization in ferrite garnets of dysprosium, holmium, and erbium (Levitin and Popov

1975), (b) high-field magnetization at 4.2 K of several R

2

M

17

single-crystalline spheres that are free to orient

themselves in the applied magnetic field (Verhoef 1990), and (c) differential susceptibility of (GdY)

3

Fe

5

O

12

iron

garnet; J, experiment; (– – –), theory (Gurtovoy et al. 1980).

523

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

magnetization in the noncollinear phase. Bend points

(or the kinks) in the magnetization curves determine

the values of the transition fields from collinear into

the noncollinear phases. Much research has been de-

voted to the high-field magnetization of ferrimagnetic

f–d intermetallic compounds. Many results have been

obtained on oriented-powder samples. Figure 5(b)

shows, for example, the typical curves for several

2–17 compounds clearly displaying the transitions

from the collinear into the canted phase.

The effect of anisotropy on the M

T

and especially

on the w

d

(differential susceptibility) behavior can be

essential in the low-field part of phase diagrams and

can give rise to additional anomalies. The region of

canted phase narrowing (the ‘‘narrow throat’’ of the

phase diagram, e.g., see Fig. 1) has to be taken as

most ‘‘dangerous’’ on that count. In this area the

angle rapidly changes with variation of the field and

temperature, which results in anomalies in w

d

.

The anomalous behavior of the differential suscep-

tibility in the vicinity of the compensation point is

attributed to the noncollinear structures in the field.

Figure 5(c) illustrates the typical behavior of the dif-

ferential susceptibility.

A temperature hysteresis of various physical

quantities may arise during a transition into the non-

collinear phase in the vicinity of the FIPTs. Butterfly-

like temperature hysteresis loops as shown in Fig. 6

have been observed experimentally in the tempera-

ture dependence of the remanent magnetization in

ErFe

2

near T

c

.

The hysteresis of the magnetization vector in ferri-

magnets near the compensation point leads to many

anomalies in the behavior of other physical quanti-

ties, e.g., of kinetic effects. This concerns galvano-

magnetic and magneto-optical phenomena (Hall effect

Figure 6

Temperature dependence of the magnetization of ErFe

2

in the vicinity of the compensation temperature (Belov

et al. 1979).

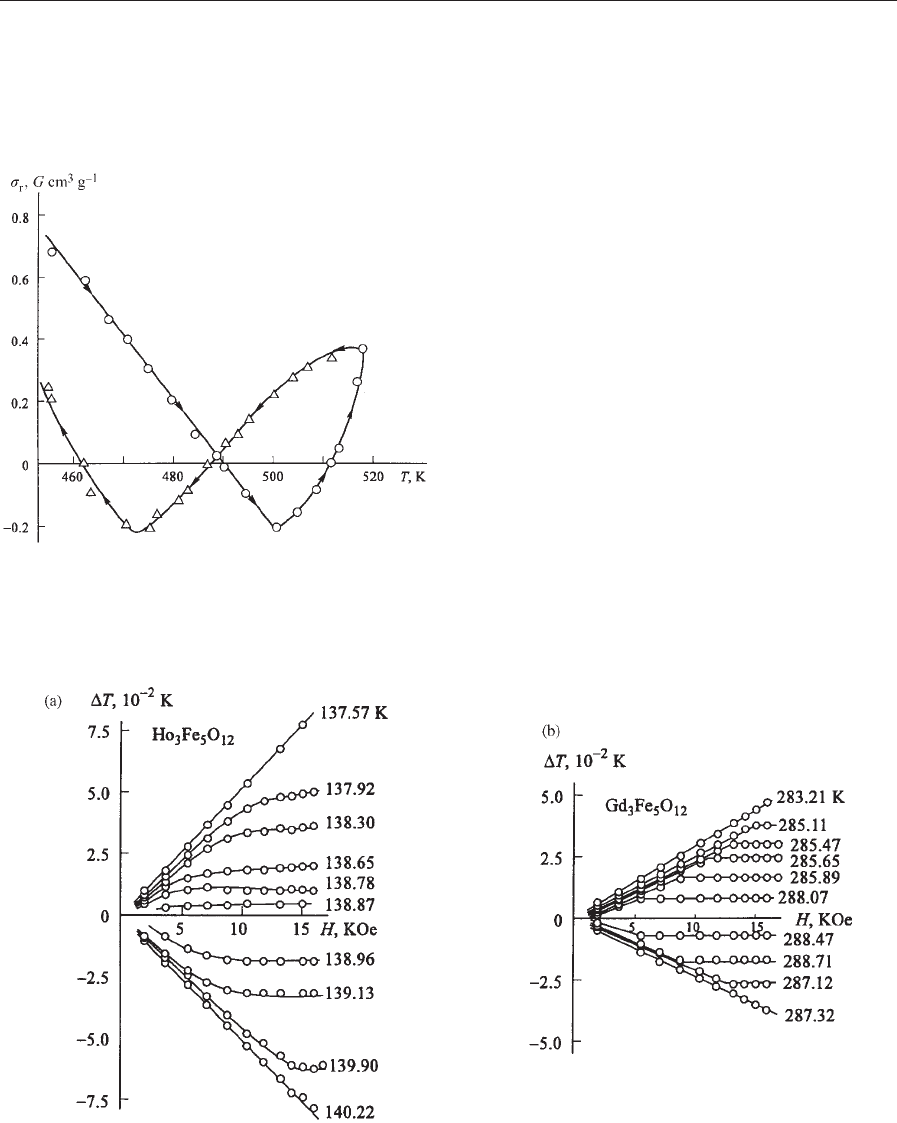

Figure 7

Magnetocaloric effect in (a) Dy

3

Fe

5

O

12

and (b) Ho

3

Fe

5

O

12

in the vicinity of the compensation temperature (Belov

et al. 1979).

524

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

and magnetoresistence, Faraday effect) in the vicinity

of the compensation point. These effects have been

studied in ferrites, in amorphous R–Co (Fe) alloys, in

the intermetallic compound Mn

5

Ge

2

, and in amor-

phous Dy–Co films.

3.2 Thermal Properties, Specific Heat,

Magnetocaloric Effect

A characteristic property of the second-order phase

transition is the kink in the isotropic curve, i.e.,

the jump of (dT/dH)

S

at the boundary between the

phases. Experimental data for some compounds are

shown in Fig. 7. It is seen that (dT/dH)

S

¼0 with

good accuracy in some phases of the gadolinium

ferrite garnets. This value perceptibly differs from

zero in the noncollinear phase of holmium and dys-

prosium ferrite garnets. This is attributed to the

large value of the anisotropy energy inherent in these

materials.

There are also specific phenomena in the context of

FIPTs related to magnetostriction, the thermal ex-

pansion coefficient, domain structure, and magnetic

structure at the local defect (Zvezdin 1995).

4. Concluding Remarks

Turning back to the question regarding the term

‘‘field-induced phase transition’’ let us note that a

broader class of phase transition is described by this

term:

(i) Ferrimagnetic–canted–ferromagnetic transitions,

which are under consideration here. Occasionally these

are referred to as spin-flop transitions by analogy with

antiferromagnets.

(ii) Metamagnetic transitions in itinerant ferrimag-

nets of YCo

2

or RCo

2

type.

(iii) Crossover level transitions, which may be due

to a field–induced crossing of the ground state levels

of the f or d ions. It should be stressed that this

crossing is accompanied by transformation of the

magnetic structure of the crystal, i.e., a magnetic

analog of the Jahn–Teller effect takes place.

(iv) First-order magnetic processes (FOMPs),

which can be due to a competition between crystal

field contributions of different order from the free

energy.

It should be emphasized that there are no distinct

boundaries between these FIPTs. Moreover, it is

often possible to find some features inherent in one

type of transition than in the others. For example, the

mechanism of the spin-flop transitions considered in

this survey is closely connected to the crossover-type

transitions. Such inter-relations of different mecha-

nisms of FIPTs are of great significance for strongly

anisotropic ferrimagnets.

See also: Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Tempera-

ture; Magnetic Systems: Specific Heat; Magnetism in

Solids: General Introduction; Magnetocaloric Effect:

From Theory to Practice; Transition Metal Oxides:

Magnetism

Bibliography

Belov K P, Zvezdin A K, Kadomtseva A M, Levitin R Z 1979

Orientational Transitions in Rare-Earth Magnets. Science,

Moscow

Berezin A G, Levitin R Z, Popov Yu F 1980 Appearance of

noncollinear magnetic structures in DyCo

5.3

near the com-

pensation temperature in strong magnetic fields. Zh. Eksp.

Teor. Fiz. (Sov. Phys. JETP) 79, 268–80

De Boer F R, Buschow K H J 1992 High-field properties of

3d–4f intermetallic compounds. Physica B 177, 199–206

Gnatchenko S L, Kharchenko N F, Konovalov O M, Pusikov

V M 1977 Magnetic phase diagram of uniaxial epitaxial

(magnetooptic and visual studies). Ukraine Fiz. Zhurnal 22,

555–64

Gurtovoy K G, Lagutin A S, Ozhogin V I 1980 Magnetic phase

diagram of iron garnets of the Y

3–,x

Gd

x

Fe

5

O

12

system in fields

up to 50 T. Zh. Eksp. Theor. Phys. (Sov. JETP) 78, 847–54

Kharchenko N F, Eremenko V V, Gnatchenko S L 1975a

Magnetooptical investigation of the noncollinear magnetic

structure of gadolinium iron garnet. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz.

(Sov. Phys. JETP) 68, 1073–90

Kharchenko N F, Eremenko V V, Gnatchenko S L, Belyi L I,

Kabanova E M 1975b Investigation of orientation transitions

and coexistence of magnetic phases in cubic ferromagnetic

GdIG. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. (Sov. Phys. JETP) 69, 1697–709

Levitin R Z, Popov Yu F 1975 In: Belov K P (ed.) Ferrimag-

netism. Moscow State University, Moscow

Verhoef R 1990 Magnetic interactions in R

2

Fe

14

B and some

other R–T intermetallics. Thesis, University of Amsterdam

Verhoef R, de Boer F R, Franse J J M, Denissen C J M, Jacobs

T H, Buschow K H J 1989 Magnetic properties of Er

2

Fe

14–x

Mn

x

C. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 80, 41–4

Verhoef R, Quang P H, Franse J J M, Radwanski R J 1990a

The strength of the R–T exchange coupling in R

2

Fe

14

B com-

pounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 83, 139–41

Verhoef R, Radwanski R J, Franse J J M 1990b Strength of the

rare earth–transition metal exchange coupling in hard mag-

netic materials and experimental approach based on high-

field magnetization measurements: application to Er

2

Fe

14

B.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 89, 176–84

Zhou G F, Li X, de Boer F R, Buschow K H J 1992a Magnetic

coupling in rare-earth compounds of the type RCo

12

B

6

.

J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 109, 265–70

Zhou G F, Li X, de Boer F R, Buschow K H J 1992b Magnetic

coupling in rare earth–nickel compounds of the type R

2

Ni

7

.

J. Alloys Comp. 187, 299–304

Zvezdin A K 1995 Field induced phase transitions. In: Buschow

K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier,

Amsterdam

Zvezdin A K, Matveev V M 1972 Some features of the physical

properties of rare-earth ferrite garnets near the compensation

temperature. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. (Sov. Phys. JETP) 62,

260–71

A. K. Zvezdin

Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia

Magnetic Phase Transitions: Field-induced (Order to Order)

525

Magnetic Properties of Dislocations

Magnetic properties originate from spin, orbital, and

free motion of electrons, as well as from the nuclear

magnetic moment. The existence of an angular mo-

mentum due to the orbital motion and to the spin of

electrons was first identified based on the normal and

anomalous Zeeman effects. In crystals, symmetry,

periodicity, and ordering play an important role in

determining the magnetic properties, which are there-

fore affected by crystal defects such as dislocations.

Whereas the question of magnetism, directly or indi-

rectly related to dislocations, has gained much atten-

tion in the past century, it is only in the recent years

that a clear and straightforward explanation has been

given to deformation-dependent magnetization, and

this is largely due to electron microscopy studies.

1. Magnetisms

1.1 Fundamental Properties

According to the Einstein’s special theory of relativ-

ity, de Broglie has shown that an electron can be

equally regarded as a particle and as a wave packet

consisting of the so-called de Broglie waves. The en-

ergy and momentum of an electron are given by

E ¼ hn ¼ mc

2

ð1 v

2

=c

2

Þ

1=2

ð1aÞ

and

P ¼ h=l ¼ mvð1 v

2

=c

2

Þ

1=2

ð1bÞ

where h is the Planck’s constant having the dimension

of action equal to energy multiplied by time. Then,

the phase velocity of the de Broglie wave (u ¼ ln)is

obtained by dividing Eqn. (1a) by Eqn. (1b) as

u ¼ ln ¼ c

2

=v ¼ cðc=vÞ4c ð2aÞ

The inequality comes from a principle that the elec-

tron velocity v never exceeds that of light c.Sincethe

velocity of the wave packet is given by dn=dð1=lÞ¼

dE=dP, it follows from Eqns. (1a) and (1b) that

dE=dP ¼ðdE=dvÞ=ðdP=dvÞ¼v ð2bÞ

(see Yukawa and Toyoda 1977). An electron is, thus,

shown to move at the velocity of a wave packet con-

sisting of de Broglie waves. The motion of an electron

engenders a magnetic moment that interacts with ex-

ternal and internal fields of electronic and magnetic

origins. These interactions are accounted for by quan-

tum mechanics (Schiff 1955, Dirac 1963, Raimes 1967,

Kittel 1971, Bullett et al. 1980).

When a material is magnetized under an external

magnetic field H, the magnetization M is written as

fMg¼wfHg¼ðm m

0

ÞfHgð3Þ

where w and m are the magnetic susceptibility and

permeability of the materials, and m

0

the permeability

in vacuum.

Equation (3) defines the magnetic properties of

materials, which are classified into the following.

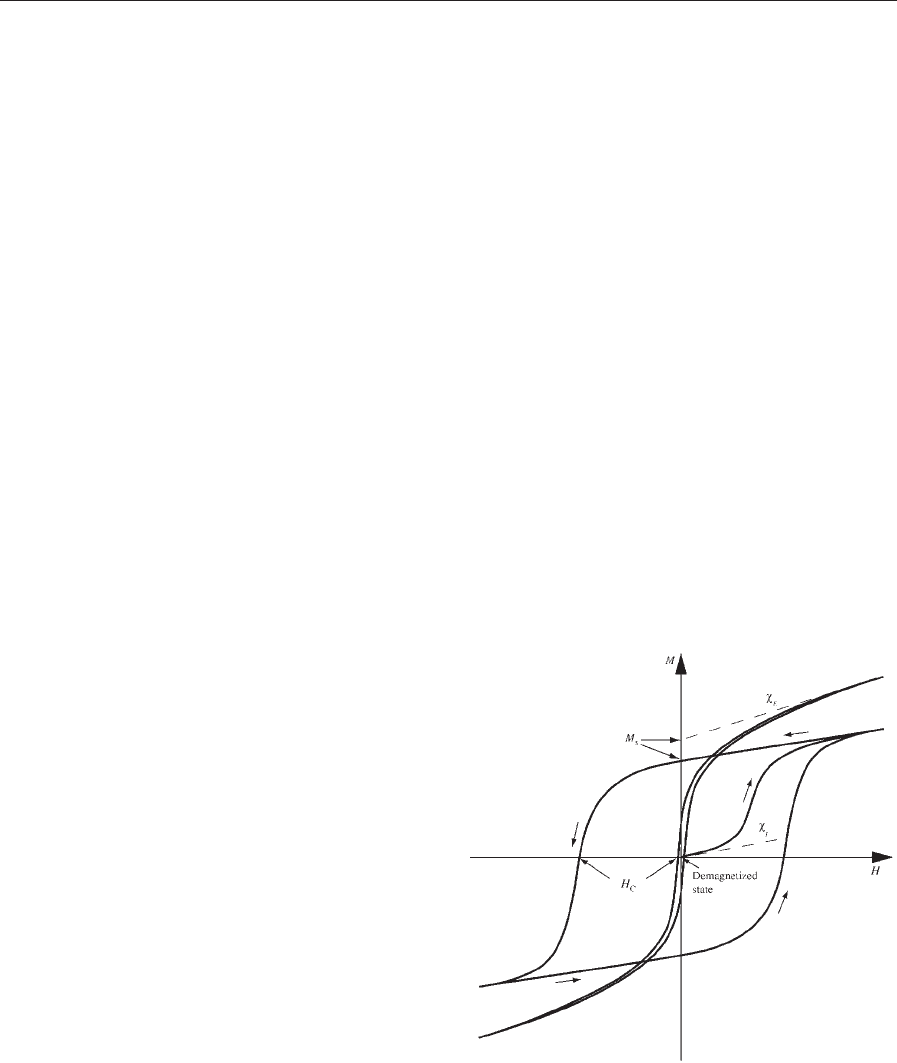

(i) Ferromagnetism. A strong magnetization due to

electron spins all aligned within a magnetic domain

sufficiently below the Curie temperature. The resist-

ance from the crystal to the motion of domain walls

induces some hysteresis on a magnetization curve as

shown in Fig. 1. w

I

is the initial susceptibility and w

E

is that measured under a high magnetic field, and H

C

is the cohesive force.

(ii) Antiferromagnetism. A weak magnetization in-

duced by application of a magnetic field due to spins

which are aligned antiparallel by superexchange in-

teraction in absence of the applied field (Anderson

1950). w

1

decreases with T below the Ne

´

el temper-

ature (Ne

´

el 1948).

(iii) Ferrimagnetism. A magnetization due to anti-

parallel electron spins as for antiferromagnetism, but

with different strength for opposite spins. It was

found in a magnetite FeO Fe

3

O

4

composed of fer-

rous ions (Fe

2 þ

) with ferromagnetism and ferric ions

(Fe

3 þ

) with antiferromagnetism (Ne

´

el 1948).

(iv) Paramagnetism. A weak magnetization propor-

tional to a magnetic field with w

1

increasing with T in

the absence of interaction among spins (Langevin

paramagnetism), or by spin bands near the Fermi

Figure 1

Magnetization curves of ferromagnetic samples with

large and small H

C

. M

S

is defined at H ¼ 0 by linear

interpolation from large H. w

I

and w

E

are the

susceptibilities at initial and high magnetic field (Izumi

2003).

526

Magnetic Properties of Dislocations

surface due to the splitting of energy levels for oppo-

site spins under a magnetic field (Pauli paramagnet-

ism). Transition metals showing no spontaneous

magnetization belong to this category (Kittel 1971).

A material comprised of extremely small ferromag-

netic domains may also show Langevin-type behavior

(superparamagnetism).

(v) Diamagnetism. A weak magnetization charac-

terized by a negative value of w and observed in

metals and organic materials without spin (feeble

diamagnetism). When w=m

0

¼1, the transition from

paramagnetism to perfect diamagnetism causes super-

conductivity, leading to the expulsion of the magnetic

field and known as the Meissner effect (Meissner and

Ochsenfeld 1933).

1.2 Magnetic Measurements

(i) Electromagnetic induction. An induction coil is

used to detect magnetization. For example, a vibra-

ting sample magnetometer (VSM), which uses a sec-

ondary coil placed around a sample, is designed to

detect an alternating voltage induced by a vibrating

sample magnetized in an applied magnetic field.

(ii) Electron spin resonance (ESR). The momentum

J or equivalently the magnetization M of an electron

is detected by resonant absorption. The application

of a magnetic field forces J to undergo Larmor pre-

cession, and this is amplified by superimposition of

an electromagnetic wave with appropriate frequency.

The spectrum and intensity of the absorption peaks

provide useful information about M. ESR is alterna-

tively called electron paramagnetic resonance (Bowers

and Owen 1955, Ingram 1968, Wertz 1968).

(iii) Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Reso-

nance arising from the magnetic spin in the nucleus.

This method picks up nuclear magneton as small as

1/1840 of the Bohr magneton. The shift of a reso-

nance peak (Knight shift) in NMR provides detailed

information about the behavior of electrons in

metallic and nonmetallic crystals including Heusler

alloys (Khoi et al. 1978). NMR is also applied to

visualize a biologic organ by construction of a three-

dimensional image (Gadian 1982) and to analyze the

structures of proteins, nucleic acids, DNA fragments,

etc. (Sarkar 1996).

(iv) Mo

¨

ssbauer effect. g-rayswithvariablewave-

length are generated by Doppler effect and utilized to

detect by resonance small energy gaps induced by nu-

clear spins. The magnetic states of atoms can be

analyzed by Mo

¨

ssbauer (1958) spectroscopy. Since the

gaps are closely related to the motion of outer shell

electrons, it can, for example, differentiate between

Fe

2 þ

and Fe

3 þ

. It has also permitted to identify a

transition from ferromagnetism to superparamagnetism

induced in Cu–Co by cold rolling (Nasu et al. 1968).

(v) Diffraction. Crystal structures and ordering

are commonly examined by x-ray, electron, and

neutron diffractions. Neutron diffraction provides

direct information about electron spins interacting

with nuclear magnetic moments. It has been used, for

example, to analyze dislocation arrangements in de-

formed Fe (Go

¨

ltz et al. 1986) and to discriminate

between ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic proper-

ties of Heusler alloys (Natera et al. 1970).

1.3 Observation of Magnetic Structures

Electrons accelerated at high voltages are commonly

employed to observe microstructures and to analyze

physical and chemical properties. Various types of

electron microscopes (EMs) or of electron micro-

scopy modes have been developed in the last several

decades, in particular, transmission EM (TEM),

scanning EM (SEM), reflection EM (REM), scan-

ning TEM (STEM), high-voltage EM (HVEM),

high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), convergent beam

electron diffraction TEM (CBEDTEM), Lorentz

TEM (LTEM), and analytical TEM.

Electrons have both particle- and wave-like prop-

erties as described in Sect. 1.1. They are deflected

mainly by protons and this is at the origin of a con-

trast in EM images and of diffraction patterns in the

case of crystals as well as quasicrystals. During elec-

tron deflection, atoms may behave as secondary

sources of signals such as x-rays, secondary electrons,

Auger electrons, and inelastically scattered electrons.

These signals serve to derive three-dimensional in-

formation, and of even higher order in the case of a

quasicrystal, on local physical and chemical proper-

ties of the material. Image and diffraction properties

are analyzed by electron wave mechanics (Thomas

1966, Hirsch et al. 1971, Williams and Carter 1998,

Fultz and Howe 2002).

The TEM method utilized to visualize magnetic

domains and domain walls is called Lorentz micro-

scopy or LTEM. The magnetic domains appear upon

defocusing of electron beams diffracted from differ-

ent domains (Fuller and Hale 1960, Hirsch et al.

1971, Williams and Carter 1998, Graef and Zhu

2001). It differs from the optical methods achieved by

Fe

3

O

4

colloid or by using magneto-optical Kerr effect

(Fowler and Fryer 1954), since the accelerated elec-

trons are capable of penetrating through thin crys-

tals. For example, LTEM is used to visualize Ne

´

el

(1954) walls in a thin foil: the fine structure called

crosstie walls in a Permalloy foil: (Huber et al. 1958)

and the fine ripples introduced by thinning of Fe, Ni,

Co and their alloys (Tsukahara 1967).

2. Dislocations

2.1 General Remarks

Dislocation is a line defect defined along the periph-

ery of a surface, which is cut, displaced uniformly,

527

Magnetic Properties of Dislocations

and then glued in an elastic continuum. The uniform

displacement, called the Burgers vector, reflects crys-

tal properties of periodicity, symmetry, and order-

ing. Atomic displacements around a dislocation and

rearrangements of atoms carried by dislocation

motion disturb the crystal properties mentioned

above and therefore affect magnetic properties. There

are excellent textbooks of elementary and advanced

theories of dislocations (Read 1953, Friedel 1964,

J. Weertman and J.R. Weertman 1967, Nabarro

1967, Hirth and Lothe 1968, Mura and Mori 1976,

Mura 1987).

2.2 Stress and Strain around a Dislocation

The Burgers vector comes into an expression of

eigendistortion b

n

ij

defined in the half plane (Mura

and Mori 1976, Mura 1987) as

b

n

23

ðfxgÞ ¼ bHðx

1

Þdðx

2

Þ for a screw dislocation

ð4aÞ

and

b

n

21

ðfxgÞ ¼ bHðx

1

Þdðx

2

Þ for an edge dislocaiton

ð4bÞ

Other b

n

ij

are zero and b is the magnitude of the

Burgers vector b. Displacements due to a screw and

an edge dislocation are shown in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b)

where the dislocation line is taken along the x

3

-axis.

Hðx

1

Þ and dðx

2

Þ are the Heaviside step function

and the delta function, respectively, defined by

Hðx

1

Þ¼

1; x

1

o0

0; x

1

40

(

ð5Þ

and

dðx

2

Þ¼

0; x

2

a0

N; x

2

¼ 0

(

ð6Þ

When b is an integer multiple of the crystal perio-

dicity, the dislocation is called perfect and if not,

imperfect or partial. The Hooke’s law is written as

(see Mura and Mori 1976, Mura 1987)

s

ij

¼ C

ijkl

ðu

k;l

b

n

lk

Þð7Þ

Here, commas denote partial derivatives of the

displacements and Einstein’s summation rule is

adopted for the repeated subscripts. C

ijkl

are the elas-

tic constants given for a cubic crystal by

C

ijkl

¼ ld

ij

d

kl

þ md

il

d

jk

þ md

ik

d

jl

þ m

0

d

ijkl

ð8Þ

where d

ij

and d

ijkl

are the Kronecker delta and l and

m are the Lame constants. Crystal anisotropy can

be defined by A ¼ 2C

2323

=ðC

1111

C

1122

Þ¼2m=ð2mþ

m

0

Þ, with m

0

¼ 0 for an isotropic material. By solving

the equations of static equilibrium given by

s

ij;j

¼ 0 ði ¼ 1; 2; 3Þð9Þ

one obtains u

i

ðfxgÞ and s

ij

ðfxgÞ around a dislocation

at rest. For a mixed dislocation u

i

ðxÞ and s

ij

ðfxgÞ

are given by superposition of its screw and edge

components.

2.3 Dislocation Cores

Core configurations are usually determined by dis-

placement of atoms from the positions determined by

elasticity in the immediate vicinity of the dislocation

center so as to minimize the total energy iteratively.

Figure 2

Schematic illustrations of (a) a screw and (b) an edge dislocations. See text for the explanation of u

i

and b

n

ij

.

528

Magnetic Properties of Dislocations

Dislocation core energy is an important factor but its

evaluation by means of atomic simulations is some-

what ambiguous for the results are often affected by

boundary conditions. It is nevertheless established

that the energy stored in the dislocation core is usu-

ally smaller by an order of magnitude than the total

energy of a dislocation. Elastic anisotropy must be

taken into account upon setting boundary conditions

for the computer simulations of dislocation cores

when m

0

jj

is large. According to Yoo (1987), m

0

con-

tributes to the strength of intermetallic compounds

notably in conjunction with the cross-slip from {111}

to {001} in L1

2

ordered alloys. Dislocations in or-

dered intermetallics have been studied by many re-

searchers and reviewed, for example, by Yamaguchi

and Umakoshi (1990) and by Vitek (1998).

3. Magnetic Properties Affected by Plastic

Deformation

3.1 General Remarks

Historically, studies of the effects of plastic deforma-

tion on magnetic properties were initiated in the early

1900s with no knowledge of the existence of disloca-

tions (Rhoads 1901, Nagaoka and Honda 1902).

These studies were focused on the ‘‘Permalloy prob-

lem’’ and ‘‘Isoperm problem’’ in 1930–40. The high

permeability of a Permalloy (Arnold and Elmen 1923)

is closely related to ordering (Dahl 1936) and disor-

dering (Kaya 1938). Anisotropy in the magnetization

arises from the alloy crystallinity as demonstrated by

Honda and Kaya (1926). The ‘‘Isoperm problem’’ was

raised in the course of the development of a permanent

magnet with high H

C

. Magnetization is also affected

by a magnetic field applied during heat treatments

(Dillinger and Bozorth 1935, Oliver and Shedden

1938, Tomono 1948, Chikazumi 1950). Typical per-

manent magnets with high H

C

are KS steel, MK steel,

Alnico 5, Cunife, Cunico, Silmanal, and RCo

5

.For

example, fine rods of ordered precipitates aligned

along /100S are responsible for the magnetic aniso-

tropy in Alnico 5 (Heidenreich and Nesbitt 1952).

The basic studies on the crystalline nature, electron

motion, and magnetostriction, which were rather ad-

vanced before 1950 in spite of several years of inter-

ruption, have contributed greatly to the recent

understanding of the magnetic properties of disloca-

tions. Some of the pioneering researches will be found

in the Bibliography section (Rhoads 1901, Nagaoka

and Honda 1902, Einstein 1905, Volterra 1907,

Ewald 1917, Laue 1918, Arnold and Elmen 1923,

de Broglie 1925, Pauli 1925, Schro

¨

dinger 1925, 1926,

Dirac 1927, Fermi 1928, Heisenberg 1928, Bloch

1929, Fock 1930, Wigner and Seitz 1933, Kramers

1934, Dillinger and Bozorth 1935, Dahl 1936, Van

Vleck 1937, Oliver and Shedden 1938, Kaya 1938,

Brown 1940, 1941, Ralhenau and Snoeck 1941, Ne

´

el

1948, Chikazumi 1950, Anderson 1950).

Investigations of the effects of dislocations on

magnetic properties have focused on the subjects of

initial and high-field magnetization in ferromagnetic

materials. In his pioneering work, Brown (1940,

1941) has given evidence that the displacements of

atoms around a dislocation (Taylor 1934, Sect. 2.2)

forces spin axes to rotate, influencing ferromagnetic

properties. Although the effect of an isolated dislo-

cation is small, a high density of dislocations intro-

duced by plastic deformation affects the magnetic

properties quite significantly (Seeger and Kronmu

¨

ller

1960, Kronmu

¨

ller and Seeger 1961, Kronmu

¨

ller 1967,

Umakoshi and Kronmu

¨

ller 1981a). Therefore, in

cyclic deformation less dominant effect appears on

the magnetic anisotropy due to reversible motion

of dislocations slowing down their accumulation

(Mughrabi et al. 1976). Aspects related to the stress

s

ij

ðfxgÞ around a dislocation will be described in

more detail in Sect. 3.2.

Another important effect is that caused by disloca-

tion motion. A strong magnetization asymmetry was

found in cold-rolled Ni

3

Fe (Ralhenau and Snoeck

1941, Chikazumi 1950, Chikazumi et al.1957),incold-

rolled Ni

3

Mn (Taoka et al. 1959), and in filed powder

of Pt

3

Fe (Bacon et al. 1963). These properties are re-

lated to the changes in atomic ordering as described in

Sect.3.3 and cyclic deformation amplifies the magnetic

effects markedly in ordered alloys (Yasuda et al.2000,

2003, Yamamoto et al. 2003, Izumi 2003), at variance

from the above-mentioned observations in pure Fe

(Mughrabi et al. 1976).

3.2 Role of Stress-fields around Dislocations

Magnetic measurements are useful in analyzing the

dislocation structures in deformed crystals by nonde-

structive testing. In measuring w

I

, w

E

, H

C

, and M

S

(Fig. 1) one should take the geometry of b and t into

account and then compare to corresponding theoreti-

cal values (Brown 1940, 1941, Seeger and Kronmu

¨

ller

1960, Kronmu

¨

ller and Seeger 1961, Kronmu

¨

ller

1967, Gessinger 1970, Willke 1972, Schroeder 1978,

Umakoshi and Kronmu

¨

ller 1981a). The magnetic en-

ergy arises from the exchange interaction between the

spins (f

A

), the magnetocrystalline anisotropy (f

K

),

the magnetization in the applied field (f

H

), the long-

range stray-field interaction coming from divergences

of magnetization (f

S

), and the magnetoelastic cou-

pling (f

M

). The last term describes the interaction

between the spontaneous magnetization and the stress

field around a dislocation.

For a cubic crystal, the magnetoelastic coupling

energy f

M

depends on the direction cosines g

i

ðfxgÞ of

the spontaneous magnetization as

f

M

¼

3

2

½ðl

100

l

111

Þd

ijkl

g

k

ðxÞg

1

ðxÞ

þ l

111

g

i

ðxÞg

j

ðxÞs

ij

ðfxgÞ ð10Þ

529

Magnetic Properties of Dislocations