Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

an intrinsic property of a single layer. As T-T

c

the

coherence length always diverges and the supercon-

ductor inherently averages over many layers in a

multilayer. This means that the anisotropic GL mod-

el described here is always applicable and x

z

(T) can

be defined.

The upper critical field of a Type II superconductor

is the field at which superconductivity is destroyed via

a second-order phase transition. Theoretically it can

be obtained by determining the temperature at which

the linearized Eqn. (1),

ac þ

1

2m

_

i

r

e

c

A

2c ¼ 0 ð3Þ

in an applied magnetic field H, along the z direction,

has a nontrivial solution. Using the Landau gauge,

A ¼H

0

y

ˆ

x, and, separating variables, one obtains the

following eigenvalue equation

_

2

2m

d

2

dx

2

þ

e

Hx

c

2

$%

c ¼ac ¼ eðHÞc ð4Þ

where H

c2

(T) is given by the implicit relation e(H) ¼

a(T) ¼_

2

/[2m

x(T)

2

], where x(T) ¼x(0)O(T

c

/T

c

T).

Equation (4) is equivalent to a Schro

¨

dinger equation

of a harmonic oscillator with frequency o

c

¼7e

7H

0

/

m

c and Landau levels. Hence, the lowest eigenvalue,

corresponding mathematically to the highest field at

which superconductivity can nucleate, is

e(H) ¼_e

H=2m

c, from which it follows that

H

c2

¼

F

0

2pxð0Þ

2

T

c

T

T

c

ð5Þ

where F

0

¼hc/e

is the superconducting flux quan-

tum. At H

c2

the density of vortices Bx

2

(T) is such

that the superconductor becomes filled with normal

cores of vortices.

From Eqn. (5) the temperature dependence of H

c2

is linear near T

c

for a three-dimensional supercon-

ductor. Note that it is the coherence lengths in the

two directions perpendicular to the applied field H

that enter into Eqn. (5).

2.2 Superconducting Thin Films

In a superconducting thin film of thickness d, T

c

will

usually decrease as d is reduced due to changes in

electronic interactions and reduced dimensionality.

Neglecting these effects, however, and by treating T

c

and d independently, one can solve Eqn. (3) for the

case of a parallel magnetic field. The appropriate

boundary condition for a free surface is

r

ie

_

c

c

#

n ¼ 0;

where n is the unit vector normal to the surface. One

can apply a solution (see Ketterson and Song 1999,

for example) of the form c ¼ uðzÞe

ik

x

xþik

y

y

and obtain

H

c28

¼

ffiffiffiffiffi

12

p

F

0

2pxðTÞd

ð6Þ

In comparison with Eqn. (5), one x(T) factor is

replaced with d/O12, and therefore the critical field

has a square root temperature dependence instead of

a linear one. These two behaviors are referred to as

2D (square root) and 3D (linear). In the perpendic-

ular direction thin films have the critical field, H

c2>

,

the same as the bulk value of Eqn. (5).

2.3 Superconducting Multilayers and Dimensional

Crossover

In a multilayer superconductivity can have either 2D

or 3D character. These behaviors and their cross-over

can be illustrated with a simple GL model. Lawrence

and Doniach (1971) first described the modified GL

free-energy functional of a series of superconducting

layers which are Josephson coupled—a 1D Josephson

lattice.

F ¼

X

n

Z

d

2

r a7c

n

7

2

þ

b

2

7c

n

7

4

þ

1

2m

_

i

r

e

c

A

c

2

$

þ Z7c

nþ1

c

n

7

2

From the free energy functional the GL equation can

be derived by variation as

ac

n

þ b7c

n

7

2

c

n

þ

1

2m

_

i

r

e

c

A

2

c

n

Zðc

nþ1

2c

n

þ c

n1

Þ¼0 ð7Þ

The first part of this equation is the 2D result,

where individual layers are indexed with n. The sec-

ond part represents the Josephson coupling energy,

scaled by the coupling parameter Z. In the limit of

strongly coupled layers, i.e., when c

n

varies slowly

across the layers, the solution is the same as the an-

isotropic GL, with the mass

m

z

¼ _

2

=2s

2

Z

Within the LD model one can solve for arbitrary

coupling of the layers, i.e., not assuming strong cou-

pling. The linearized GL equation in a parallel mag-

netic field becomes

_

2

2m

d

2

dx

2

þ

_

2

m

z

s

2

1 cos

2eHxs

_c

c ¼ac

From this equation the critical field follows as

H

c28

¼

F

0

2ps

2

ð1 s

2

=2x

z

ðTÞ

2

Þ

1=2

m

x

m

z

230

Films and Multilayers: Conventional Superconducting

This equation leads to a divergence of the critical field

at T

0

defined by x

z

(T

0

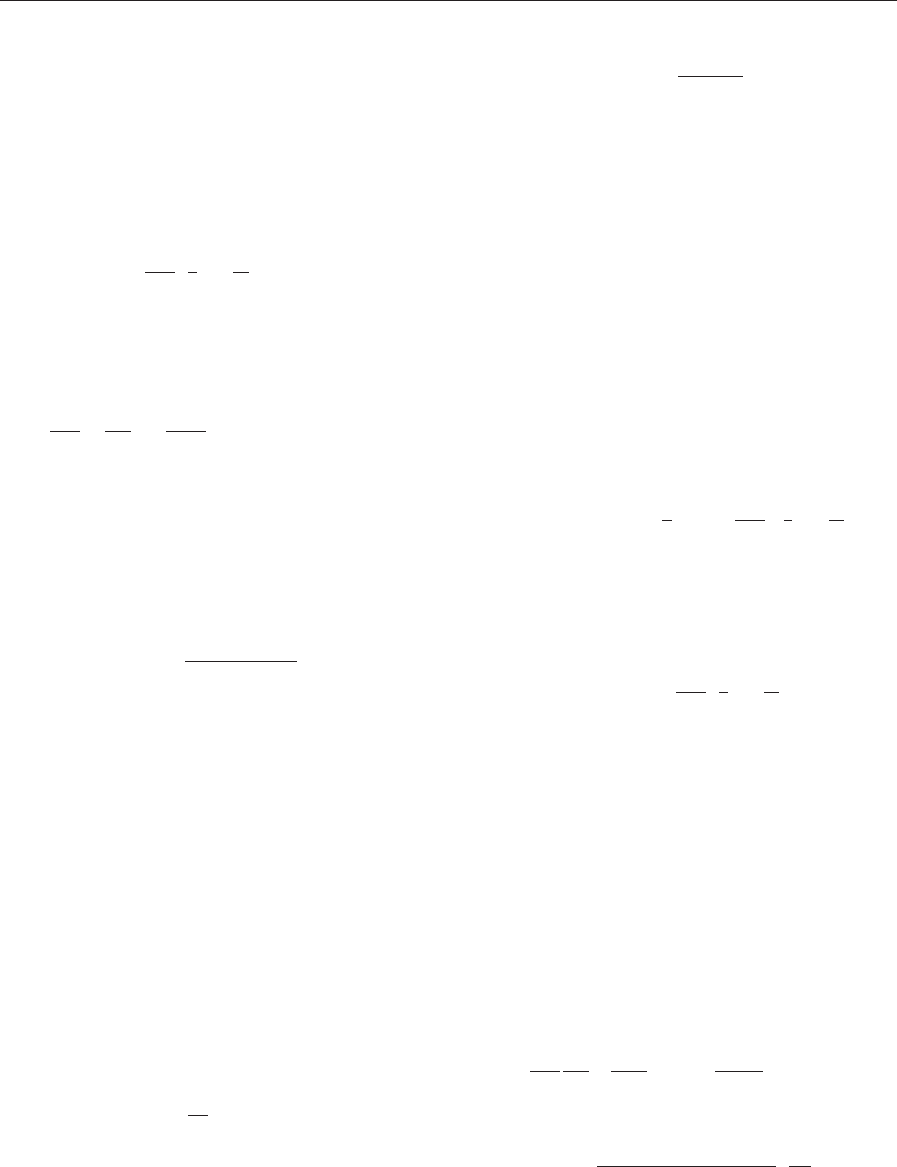

) ¼s/O2 (see Fig. 3).

Above T

0

the multilayer behaves as a 3D aniso-

tropic superconductor. As the temperature is lowered

the coherence length decreases its zero temperature

value. When the coherence length becomes compa-

rable to the spacing of the superconducting layers,

the normal cores of the vortices can fit between the

superconducting layers where they have a reduced

pair-breaking effect. Hence the critical field will in-

crease at this temperature and in the LD model the

critical field becomes infinite. In reality the critical

field will not diverge because it is limited by the single

film value, such as that described above. However,

the essential physics is captured in this simple model

for dimensional crossover. Below T

0

the vortices

change from Abrikosov-like to Josephson-like when

the X layers are nonsuperconducting.

Dimensional crossover was experimentally con-

firmed by a number of experimental reports. The first

most compelling result was by Ruggiero et al. (1980).

Other reports can be found in the reviews mentioned

above. Ruggiero et al. studied Nb/Ge (S/I) multilay-

ers as a function of different layer thicknesses in or-

der to observe dimensional crossover. Figure 4 shows

the upper critical field of several Nb/Ge multilayer

samples with 3D, 2D, and crossover behavior. Later

studies have observed the crossover more elaborately

in S/N systems (see, for example, Banerjee et al.

1983).

2.4 Takahashi–Tachiki Effect in S/S

0

Multilayers

Takahashi and Tachiki (1986a, 1986b) examined the

behavior of the upper critical field in S/S

0

multilayers

within a microscopic theory. For the case of widely

differing diffusion constants, i.e., differing x, but with

similar bulk T

c

of the two superconducting layers,

they observed two possible solutions for nucleation of

superconductivity. One solution is for nucleation of

the superconducting order parameter in the dirty

superconductor, here labeled S, and the other for

nucleation of superconductivity in the clean super-

conductor, or S

0

, layers. The actual critical field will

be the larger of the two solutions.

The Takahashi–Tachiki effect is a discontinuity in

the parallel upper critical field exhibiting an upward

curvature at low temperatures. This happens when

Figure 3

Temperature dependence of the upper critical field for

the Josephson coupled Lawrence–Doniach (LD) model.

Comparison is shown with the 3D GL and 2D GL

models. In reality the critical field will not diverge at T

0

as in the LD model, but will cross over to a 2D behavior.

Below T

0

vortices fit between the superconducting layers

and become Josephson type. Above T

0

vortices are

averaging over several layers and are Abrikosov-type.

Figure 4

Upper critical fields near T

c

for Nb/Ge multilayers. As

the Ge layer thickness increases the system evolves from

3D behavior to ‘‘crossover’’ behavior and finally to

decoupled 2D. Solid lines are fits to the theory (after

Ruggiero et al. 1980).

231

Films and Multilayers: Conventional Superconducting

nucleation of superconductivity switches from S

0

to S

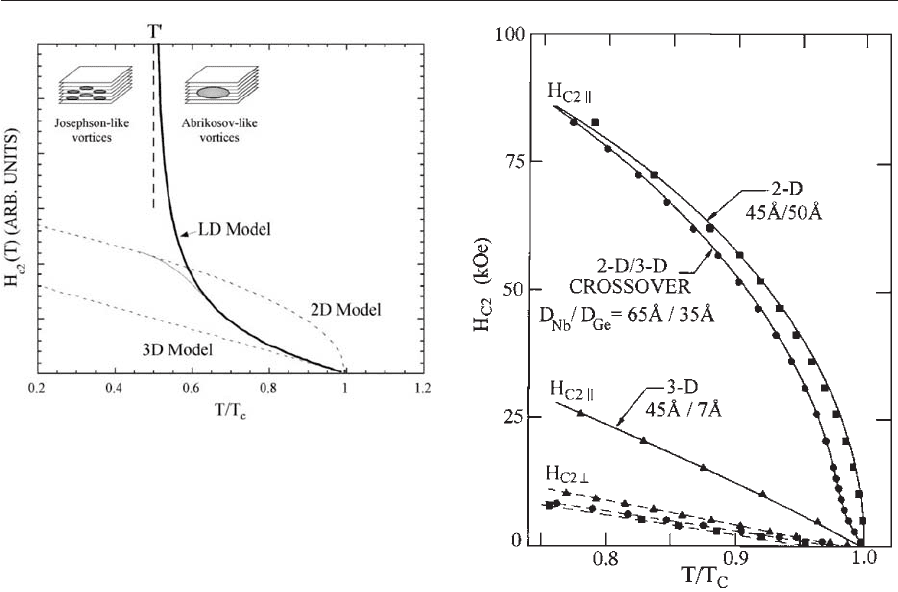

layers. Figure 5 illustrates the behavior of the critical

field for a particular set of material parameters where

this effect may be observed. The effect is only ob-

served for a ratio of diffusion constants above a cer-

tain value, or equivalently above a minimum x

S

0

/x

S

.

For temperatures very close to T

c

the parallel crit-

ical field has the usual linear 3D behavior. At some

temperature below T

c

there is a crossover to 2D be-

havior with nucleation in the S

0

layers. As the tem-

perature decreases further and the coherence length

becomes shorter than d

S

, the order parameter is con-

strained inside the S layers and superconductivity

behaves as it would in the bulk S material which has a

high critical field. At T* superconductivity crosses

over from being nucleated in the S

0

to the S layers and

there is a discontinuity in the critical field.

The theoretical prediction of the effect was subse-

quently experimentally confirmed in the Nb/NbTi

multilayer system by Karkut et al. (1988). For the

proper choice of materials, as in Nb

0.6

Ti

0.4

and Nb,

the two layers have similar T

c

but their diffusivities

differ by a factor of 20. Karkut et al. observed an

upturn in the parallel critical field at a particular

temperature T* as predicted by the Takahashi–

Tachiki theory.

See also: Superconducting Materials, Types of;

Superconducting Thin Films: Materials Preparation

and Properties; Superconducting Thin Films: Multi-

layers

Bibliography

Banerjee I, Yang Q S, Falco C M, Schuller I K 1983 Aniso-

tropic critical fields in superconducting superlattices. Phys.

Rev. B 28, 5037–40

Buzdin A I, Bulaevskii L N, Panyukov S V 1982 Critical-cur-

rent oscillations as a function of the exchange field and

thickness of the ferromagnetic metal (F) in an S–F–S Jose-

phson junction. JETP Lett. 35, 178–80

Fulde P, Ferrell R A 1964 Superconductivity in a strong spin-

exchange field. Phys. Rev. 135A, 550–63

Huebener R P 1979 Magnetic Flux Structures in Superconduc-

tors. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Jiang J S, Davidovic D, Reich D H, Ghien C L 1995 Oscillating

superconducting transition temperature in Nb/Gd multilay-

ers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 314–7

Karkut M G, Matijasevic V, Antognazza L, Triscone J -M,

Missert N, Beasley M R F, 1988 Anomalous upper critical

fields of superconducting multilayers: verification of the

Takahashi–Tachiki effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1751–4

Ketterson J B, Song S N 1999 Superconductivity. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK

Larkin A I, Ovchinnikov Yu N 1964 Inhomogeneous state of

superconductors. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 47, 1136 [Sov. Phys.

JETP 20, 762 (1965)]

Lawrence W E, Doniach S 1971 Theory of layer-structure su-

perconductors. In: Kanda E (ed.) Proc. 16th Int. Conf. on

Low Temperature Physics, pp. 361–2

Matijasevic V, Beasley M R 1987 Superconductivity in super-

lattices. In: Shinjo T, Takada T (eds.) Metallic Superlattices:

Artificially Structured Materials. Elsevier Science, The Neth-

erlands

Mu

¨

hge Th, Garif’yanov N N, Goryunov Yu V, Khaliullin G G,

Tagirov L R, Westerholt K, Garifullin I A, Zabel H 1996

Possible origin for oscillatory superconducting transition

temperature in superconductor/ferromagnet multilayers.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1857–60

Radovic Z, Dobrosavljevic-Grujic L, Buzdin A I, Clem J R

1988 Upper critical fields of superconductor–ferromagnet

multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 38, 2388–93

Ruggiero S T, Barbee T W, Beasley M R 1980 Superconduc-

tivity in quasi-two-dimensional layered composites. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 45, 1299–302

Ruggiero S T, Beasley M R 1984 Synthetically layered super-

conductors. In: Chang L L, Giessen B C (eds.) Synthetic

Modulated Structures. Academic Press, New York

Ryazanov V V, Oboznov V A, Rusanov A Yu, Veretennikov A

V, Golubov A A, Aarts J 2001 Coupling of two supercon-

ductors through a ferromagnet: evidence for a p-junction.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2427–30

Schuller I K, Guimpel J, Bruynseraede Y 1990 Artificially lay-

ered superconductors. MRS Bull. 15, 29–36

Takahashi S, Tachiki M 1986a Theory of the upper critical field

of superconducting superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 33, 4620–31

Takahashi S, Tachiki M 1986b New phase diagram in super-

conducting superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 34, 3162–4

V. Matijasevic

Oxxel GmbH, Germany

Fullerene Formation

Diamond and graphite constitute two natural crys-

talline forms of pure carbon. Their properties and

characteristics are completely different, a fact that

can be explained in terms of the way carbon atoms

Figure 5

Schematic of the Takahashi–Tachiki effect (after

Takahashi and Tachiki (1986b).

232

Fullerene Formation

bond to each other within the structure. For dia-

mond, sp

3

hybridization prevails, four bonds from

each carbon atom being directed towards the corners

of a regular tetrahedron. The resulting three-dimen-

sional network is extremely rigid, which is one reason

for the hardness of diamond. In graphite, sp

2

hy-

bridization results in three bonds per carbon atom,

distributed evenly (1201) in the xy plane, with a weak

p bond along the z axis. The C–C bond length is

1.42 A

˚

, and the sp

2

set creates the honeycomb (hex-

agonal) lattice typical of a single sheet of graphite.

The p (van der Waals) bond is responsible for weak

interactions between the layers, which are 3.35 A

˚

apart.

For generations, diamond and graphite were the

only known allotropes of carbon. However, in 1985 a

new form of carbon, buckminsterfullerene (C

60

)

(Kroto et al. 1985), appeared on the scene.

C

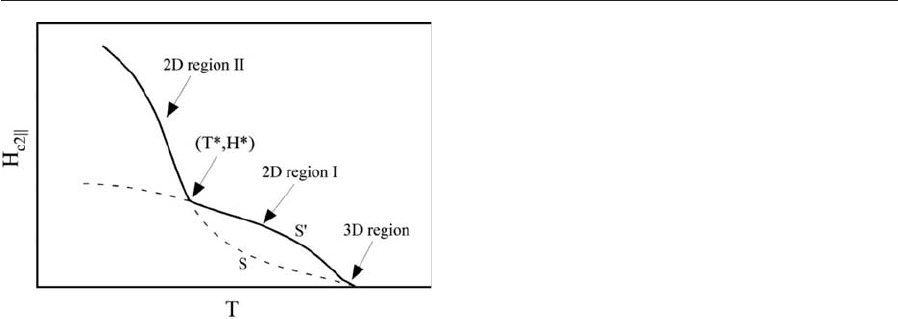

60

is a soccer-ball-like cage composed of 60 car-

bon atoms with a diameter of 7.1 A

˚

. The shape and

symmetry of C

60

is that of a truncated icosahedron,

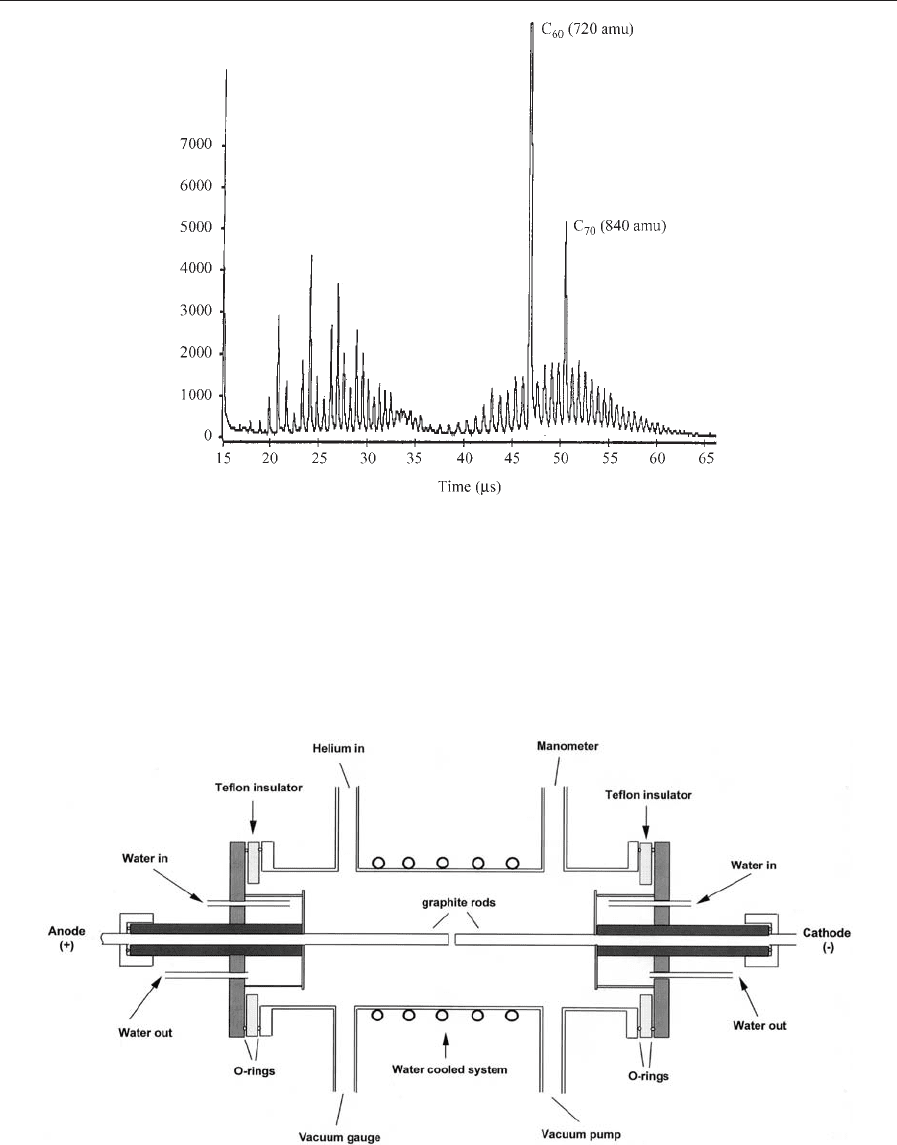

consisting of 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons (Fig. 1).

Curvature is due to the presence of the pentagons.

The relationship between the vertices, faces, and edg-

es of C

60

finds expression in Euler’s law (see Sect. 3).

C

60

is but one example of closed structures made up

of any number of hexagons (except one) and 12 pen-

tagons now styled fullerenes.

1. Discovery of C

60

One part of this story starts in the 1970s, when

the chemists Harry Kroto and David Walton at

Sussex University were studying cyanopolyynes

H(CC)

n

CN (chain-like molecules, in which car-

bon atoms are linked by alternating single and triple

bonds, being end-capped with hydrogen and nitro-

gen). These compounds display characteristic micro-

wave spectra commensurate with their linear dipole

structure (Kroto 1992).

The two Sussex scientists together with Anthony

Alexander (a BSc-by-thesis student) succeeded in

preparing HC

5

N and, with Colin Kirby (a research

student), HC

7

N. Subsequently, with Canadian as-

tronomers Takeshi Oka and co-workers, radio waves

emitted from HC

n

N(n ¼5, 7, 9) in the center of our

galaxy were detected (Kroto 1992).

In 1984 Kroto visited Robert Curl at Rice Univer-

sity (Houston, Texas) and was introduced to Richard

Smalley, who was generating clusters of atoms by la-

ser-vaporizing solids. Kroto was interested in subject-

ing graphite to this treatment in order to simulate the

conditions thought to prevail in red giant stars.

In late August 1985 Kroto traveled to Houston in

order to participate in the graphite experiment, which

involved evaporating carbon from the surface of a

rotating graphite disk in the presence of a high density

helium flow. The resulting carbon clusters were al-

lowed to expand though a nozzle and were detected by

a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Kroto et al.1985).

The mass-spectral profile for carbon, obtained in

these experiments, had in fact already been observed

by Rohlfing et al. (1984) and consisted of two main

groups of clusters: (a) those with low mass (o30

carbon atoms) consisting of odd numbers of carbon

atoms and (b) high-mass clusters (436 atoms) con-

taining only even numbers of carbon atoms (Fig. 2).

Rohlfing et al. (1984) proposed that clusters with less

than nine carbon atoms were linear chains, and that

the odd masses between 11 and 23 were due to rings.

No comment was made regarding the structure of

higher clusters other than that they were exceptional

and possibly carbyne-like (consisting of linear carbon

chains with alternating single and triple bonds, i.e.,

polyynes).

In the experiments carried out at Rice University,

the dominant role played by the cluster of 60 carbon

atoms was noted and its stability was ascribed to the

unique nature of the truncated icosahedral cage (see

above) without ‘‘dangling’’ bonds (Fig. 1). C

60

was

named buckminsterfullerene by the Sussex/Rice

Figure 1

(a) Buckminsterfullerene (C

60

), the third carbon

allotrope, discovered in 1985. (b) C

70

with D

5h

symmetry. (c) C

240

, an icosahedral giant fullerene.

233

Fullerene Formation

Figure 2

Mass-spectral profile obtained by the Sussex/Rice team, showing C

60

and C

70

as the most intense peaks. Additionally,

they observed two groups of clusters: those with lower mass (o30 carbon atoms) consisting of odd numbers of

carbon atoms and high-mass clusters (436 atoms) exhibiting only even numbers of carbon atoms (courtesy of

H. W. Kroto).

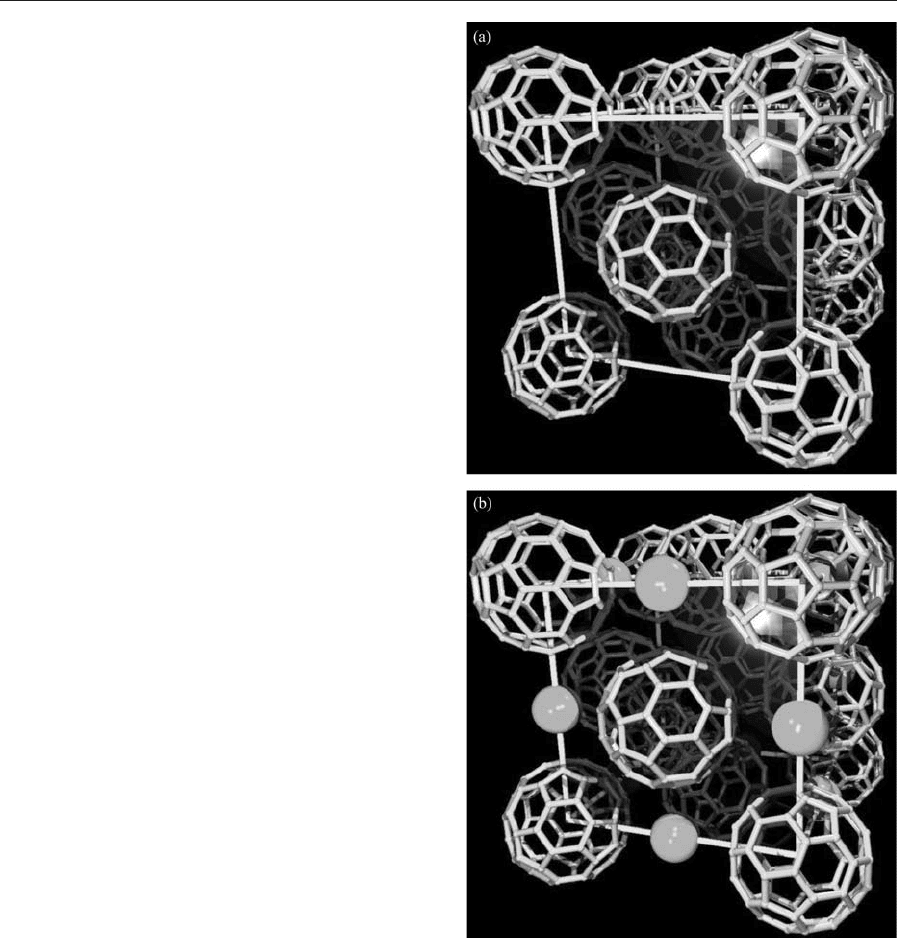

Figure 3

Schematic diagram of a d.c. arc discharge chamber used for fullerene production.

234

Fullerene Formation

team, in recognition of the US architect R. Buckm-

inster Fuller, who designed geodesic domes with sim-

ilar topologies.

In order to verify the structure of C

60

, bulk quan-

tities were needed. However, at the time only pico-

gram amounts were available.

2. Bulk Production and Characterization of C

60

In 1990 Kra

¨

tschmer and Huffman succeeded in pre-

paring milligram quantities of C

60

, accompanied by

smaller amounts of higher fullerenes (e.g., C

70

,C

76

,

etc.) by extracting soluble material from soot deposits

formed in an arc discharge between graphite elec-

trodes in a helium atmosphere (Fig. 3). Subsequently,

C

60

and C

70

were separated and characterized by the

Sussex team using conventional chromatography and

NMR techniques. Fullerenes have also been obtained

by combustion and by pyrolysis of hydrocarbons

such as naphthalene.

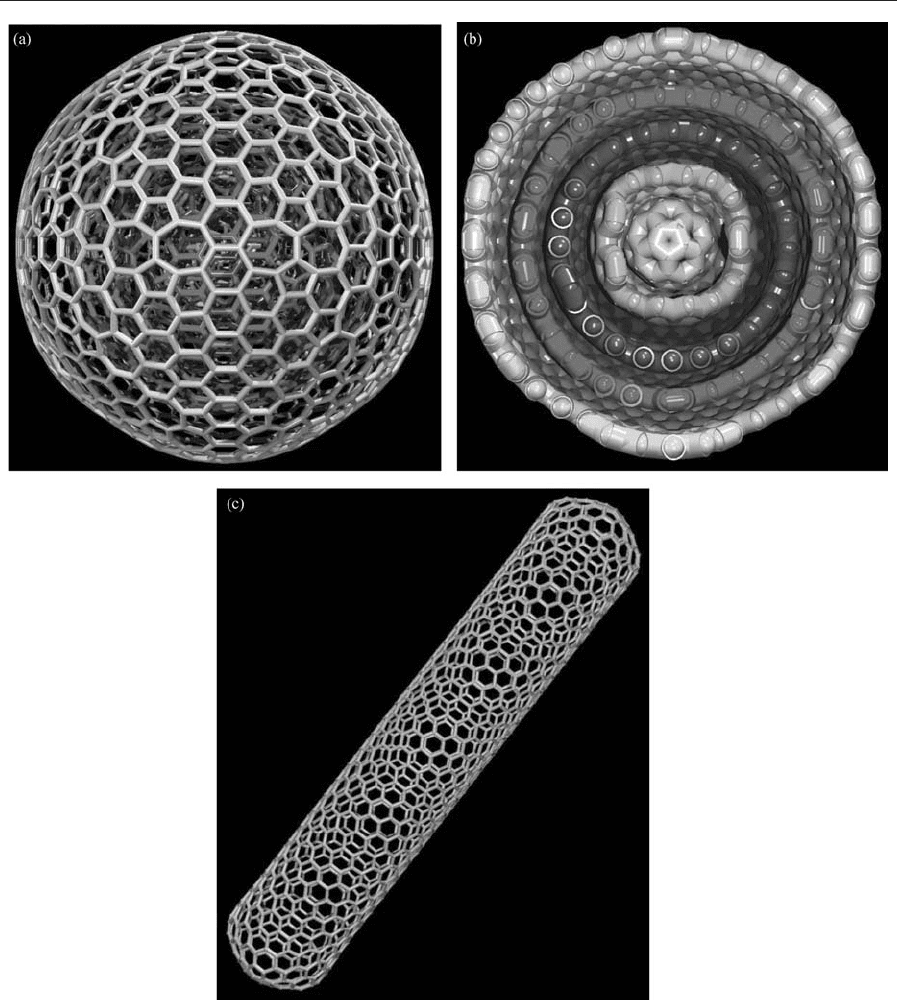

In the solid state, C

60

crystallizes as a cubic struc-

ture with a lattice constant of 14.17 A

˚

, a nearest-

neighbor C

60

–C

60

distance of 10.02 A

˚

, and a density

of 1.72 g cm

3

(Fig. 4(a)). At room temperature, C

60

clusters rotate rapidly in an f.c.c. structure about

their lattice positions (Tables 1 and 2). However, a

transition to a simple cubic phase (a ¼14.17 A

˚

con-

sisting of four C

60

clusters per unit cell) occurs below

261 K (Tanigaki and Prassides 1995).

The first fullerene isolated other than C

60

, was C

70

(isolated by Taylor et al.), which consists of two C

60

hemispheres connected by a ring of 10 carbons (re-

sembling a rugby ball; Fig. 1). Crystalline C

70

has

different crystallographic arrangements depending on

the temperature: the most stable phases are the

f.c.c. structure with a lattice constant of 15.01 A

˚

and

the hexagonal phase with a ¼b ¼10.56 A

˚

and

c ¼17.18 A

˚

. Higher fullerenes such as C

76

,C

78

,C

82

,

C

84

, were subsequently isolated and characterized.

3. Geometry of Fullerenes

Fullerenes are closed polyhedrons made of carbon,

and understanding their geometry may eventually

shed light on the way they are constructed. As men-

tioned above, Euler’s law expresses the proportions

of polygon types (pentagons and hexagons) needed to

form C

60

. For any polyhedron FE þV ¼w, where F

is the number of faces, E is the number of edges, V is

the number of vertices, and w is the Euler character-

istic, which is a geometric invariant that describes

structures with the same shape or topology. For all

closed polyhedrons w ¼2. For example, in C

60

, F ¼32

(12 pentagons and 20 hexagons), E ¼90, V ¼60, and

w ¼2; for C

70

, F ¼37 (12 isolated pentagons, 25 hex-

agons, and D

5h

symmetry), E ¼105, V ¼70, and

w ¼2. All closed polyhedrons have the same topology

as the sphere, which means that any polyhedron can

be transformed into a sphere by bending and stretch-

ing without cutting or tearing. In addition, no full-

erene can be formed from an odd number of atoms.

For a ‘‘graphitic’’ network, considering only pen-

tagonal, hexagonal, heptagonal, and octagonal rings

Figure 4

(a) F.c.c. crystal structure of C

60

. (b) Structure of the

M

1

C

60

intercalated compounds showing the metal

intercalated between the C

60

spheres. Note that the size

of the intercalated atoms has been chosen arbitrarily.

235

Fullerene Formation

of carbon, Euler’s law can be written:

N

5

N

7

2N

8

¼ 6w ¼ 12 ð1Þ

where N

n

is the number of polygons with n (5, 7, and

8) sides. As Eqn. (1) shows, N

5

, N

7

, and N

8

are de-

fects in a ‘‘graphitic’’ structure which contribute to

the curvature and topology of the arrangement (Terr-

ones and Mackay 1992). N

6

is absent since hexagons

do not contribute to curvature of the structure. In

addition, Eqn. (1) demonstrates that it is possible to

introduce heptagons and octagons in a closed graphi-

tic cage if their proportion is maintained. Therefore,

if pentagons are present in C

60

, one cannot rule out

the presence of higher-membered rings (e.g., hepta-

gons) in larger fullerenes.

It turns out that there are 1812 possible ways of

arranging 12 pentagons and 20 hexagons in C

60

,so

what is special in buckminsterfullerene? It is the

smallest cage in which each pentagon is surrounded

by five hexagons, thus leading to icosahedral (I

h

)

symmetry (the highest symmetry than can be ob-

tained by a polyhedron). This suggests that curved

graphite follows an isolated pentagon rule to form

fullerenes, and explains why smaller fullerenes (less

than 60 atoms) are difficult to produce.

4. Fullerene Gro wth

Although the precise growth mechanism leading to

C

60

and other fullerenes is not well understood, it is

worth reviewing ways in which they might be formed.

First, the mass spectrometry data obtained by laser

vaporization and arc discharge experiments indicate

that there are three main groups of structures, de-

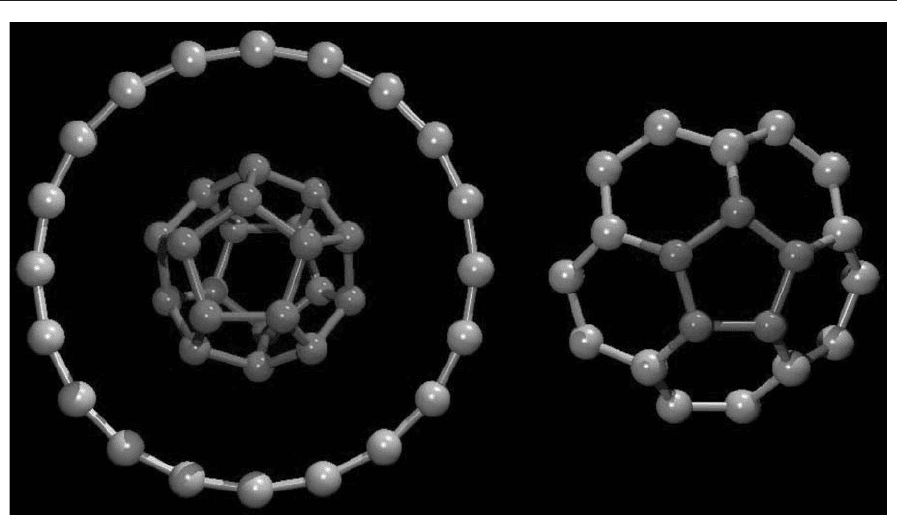

pending upon the size: chains, rings, and fullerenes. In

other words, for a small number of atoms (o10) car-

bon chains are the most stable (one dimension); sub-

sequently rings start to appear (410 atoms), thus

avoiding dangling bonds at the ends (two dimensions);

and finally fullerenes emerge in order to avoid dan-

gling bonds in larger, three-dimensional structures.

According to Euler’s law, the smallest fullerene that

can possibly exist is the dodecahedron with 20 atoms

or 12 pentagons (C

20

; Fig. 5). Although this structure

is quite regular (one of the five Platonic solids), with

icosahedral symmetry, building it from sp

2

carbons

introduces considerable strain. This is because the

internal angle in a regular pentagon is 1081, which

differs substantially from the internal (hexagon) 1201

angles in graphite. Therefore, in order to relieve

this strain, hexagons are required to stabilize larger

fullerenes. At the same time, with 20 atoms, it is

also possible to obtain a ring (cyclic polyyne) or a

Table 1

Physical constants for C

60

.

Quantity Value

Average C–C distance 1.44 A

˚

C–C bond length on a pentagon 1.46 A

˚

C–C bond length on a hexagon 1.40 A

˚

C

60

mean ball diameter 7.10 A

˚

C

60

ball outer diameter 10.34 A

˚

Moment of inertia 1.0 10

43

Kg m

2

Volume per C

60

1.87 10

22

cm

3

Number of distinct carbon sites 1

Number of distinct C–C bonds 2

Binding energy per atom 7.40 eV

Heat of formation (per g 10.16 Kcal

carbon atom)

Electron affinity 2.6570.05 eV

Cohesive energy per atom 1.4 eV

Spin–orbit splitting of carbon (2p) 0.000 22 eV

First ionization potential 7.58 eV

Second ionization potential 11.5 eV

Optical absorption edge 1.65 eV

Source: Dresselhaus et al. (1995).

Table 2

Physical constants for crystalline C

60

in the solid state.

Quantity Value

F.c.c. lattice constant 14.17 A

˚

C

60

–C

60

distance 10.02 A

˚

C

60

–C

60

cohesive energy 1.6 eV

Tetrahedral interstitial site

radius

1.12 A

˚

Octahedral interstitial site

radius

2.07 A

˚

Mass density 1.72 g cm

3

Molecular density 1.44 10

21

cm

3

Compressibility (dlnV/dP) 6.9 10

12

cm

2

dvn

1

Bulk modulus 6.8–8.8 GPa

Young’s modulus 15.9 GPa

Transition temperature (T

01

) 261 K

dT

01

/dp 11 K bar

1

Volume coefficient of thermal

expansion

6.1 10

5

K

1

Optical absorption edge 1.7 eV

Work function 4.770.1 eV

Velocity of sound, v

t

2.1 10

5

cm s

1

Velocity of sound, v

l

3.6–4.3 10

5

cm s

1

Debye temperature 185 K

Thermal conductivity (300 K) 0.4 W m

1

K

1

Electrical conductivity 1.7 10

7

Scm

1

Phonon mean free path 50 A

˚

Static dielectric constant 4.0–4.5

Melting temperature 1180 1C

Sublimation temperature 434 1C

Heat of sublimation 40.1 kcal mol

1

Latent heat per C

60

unit 1.65 eV

Source: Dresselhaus et al. (1995).

236

Fullerene Formation

corannulene-like molecule (a bowl-shaped structure

composed of one pentagon surrounded by five hex-

agons; Fig. 5). Various theoretical simulations have

been carried out in order to ascertain which is the

most stable structure composed of 20 atoms. The re-

sults show that, depending upon the computational

method used, the ring, the corannulene-like molecule,

and the dodecahedron are stable and feasible. How-

ever, for fullerene formation (under nonequilibrium

conditions), corannulene and the dodecahedron might

be relevant due to the presence of pentagons in their

structures. Nevertheless, neither of them has ever been

observed as a stable product.

It is worth noting that fullerenes are formed in a

plasma at 3500 1C and under these conditions a wide

variety of carbon clusters are present, e.g., dimers,

trimers, rings, and small clusters. Thus, structures of

the corannulene type or the dodecahedral C

20

may

play a crucial role in the formation of C

60

since C

2

or

bigger units can become attached to the pentagons,

thus stimulating growth.

Two main mechanisms have been proposed to

account for fullerene formation (Dresselhaus et al.

1995). They are based upon: (a) absorption of C

2

units and (b) Stone–Wales (S–W) transformations.

The absorption of a C

2

cluster creates an extra hex-

agon within the structure; therefore, the addition of

several C

2

units into a fullerene would generate a

larger cage. An S–W transformation involves rotating

aC

2

unit by 901, thus changing the symmetry but

maintaining connectivity. A combination of these

two mechanisms is necessary in order to attain a sta-

ble ‘‘graphitic’’ cage. Nevertheless, the amount of

energy involved in an S–W transformation is large

(B7 eV). In this context, it has been shown that au-

tocatalytic effects might overcome the potential bar-

rier involved in this type of transformation (Eggen

et al. 1996). It is also worth noting that fullerenes

smaller than C

60

have been detected only in mass

spectrometers, with one exception being the D

6h

isomer of C

36

, isolation of which has been claimed

(Piskoti et al. 1998).

5. Endohedral Complexes, Intercalated

Compounds and Superconductivity

Kroto et al. (1985) suggested that it should be pos-

sible to encapsulate atoms within the C

60

cage. Short-

ly afterwards a Rice University student, Jim Heath,

succeeded in trapping lanthanum in C

60

by laser va-

porizing a graphite disk impregnated with LaCl

3

(Heath et al. 1985). Following the bulk production

of C

60

, fullerenes containing encapsulated elements,

denoted M@C

n

, have been described, e.g., Ar@C

60

,

He@C

60

, Hf@C

28

, Ti@C

28

, U@C

28

,U

2

@C

28

,

Zr@C

28

, U@C

36

, Co@C

60

, Sc@C

74

, Er@C

82

,

La@C

82

,La

2

@C

82

, Sc@C

82

,Sc

2

@C

82

,Sc

3

@C

82

,

La@C

84

,La

2

@C

84

, etc. (Dresselhaus et al. 1995).

The separation and isolation of these endohedrals is

difficult because the amounts available are minute,

Figure 5

Possible isomers of C

20

: (a) ring, (b) cage, and (c) bowl (corannulene-like molecule).

237

Fullerene Formation

there are solubility problems, and the products may

be oxygen sensitive.

In 1991 Haddon and co-workers succeeded in inter-

calating alkali metals with C

60

in order to produce

materials of stoichiometry M

3

C

60

(M ¼K, Rb, Cs).

These products displayed a relatively high, supercon-

ducting, value of T

c

(18–33 K) (Tanigaki and Prassides

1995). Other stable phases of intercalated C

60

were

Figure 6

(a) Graphitic onion-like structures: concentric giant fullerenes with heptagons and additional pentagons. (b) Cross-

section of the structure shown in (a) exhibiting concentric shells. (c) Elongated fullerene: a carbon nanotube.

238

Fullerene Formation

prepared (e.g., M

1

C

60

,M

3

C

60

,andM

6

C

60

;Fig.4(b)).

All possess lattice constants greater than that of C

60

(a ¼14.24 A

˚

) due to the introduction of the metal ion

into the crystal phase (Fig. 4(b)). It is important to note

that superconductivity only arises when the tetrahedral

and octahedral sites of C

60

are fully occupied by alkali

atoms, thus creating a M

3

C

60

structure. Other stable

phases and crystal structures with one, two, four, and

six alkali ions per unit cell have been also described.

6. Giant Fullerenes

In 1992 Daniel Ugarte discovered that carbon soot

(generated in plasma arcs), under high-energy elec-

tron irradiation, produced what were effectively nest-

ed giant fullerenes, termed ‘‘graphitic onions’’ (Figs.

6(a) and 6(b)). It is interesting to note that in 1980

Iijima observed similar round structures in amor-

phous carbon films prepared by vacuum deposition

(the morphology was proposed by Kroto and McKay

in 1988). These closed polyhedrons possess millions

of carbon atoms. It has been shown theoretically

(Terrones et al. 1995) that the high sphericity of the

onions is due to the presence of heptagons and oc-

tagons (Figs. 6(a) and 6(b); Eqn. (1)).

7. Uses of Fullerenes

Current fullerene research is developing rapidly and

due to their exceptional properties (Tables 1 and 2),

various applications can be envisaged. In particular,

the optical properties have facilitated the fabrication

of photodiodes and photovoltaic and photorefractive

devices, etc. Fullerenes, in conjunction with conduct-

ing polymers, could give rise to C

60

-based transistors

and rectifying diodes. However, it should be pointed

out that most of these C

60

devices are unstable in air

due to the diffusion and photodiffusion of dioxygen

into the large interball sites present in the solid.

From the catalysis point of view, fullerenes can be

useful in the hydrocarbon refining industry, where an

active catalyst is needed to enhance the efficiency with

which hydrogen is used. Fullerenes can be used as a

source of pure carbon in order to generate high-pu-

rity carbon allotropes such as diamond or nanotubes

(see Sect. 8). In the nanotechnology area, C

60

and

other ‘‘graphitic’’ particles may prove useful as scan-

ning tunneling microscopy (STM) tips, lubricants,

sensors, and other nanoscale devices.

Finally, C

60

has proved to be useful as an efficient

inhibitor of HIV enzymes and research related to

cancer treatments is underway. Therefore, this excit-

ing area of research is likely to give birth to a new

technology in the twenty-first century.

8. Elongated Fullerenes (Nanotubes)

The fullerenes reviewed above consist of closed,

round cages. However, it is possible to generate

elongated fullerenes, known as nanotubes (Fig. 6(c)).

Iijima (1991) reported the existence of these struc-

tures, consisting of concentric graphite tubes, pro-

duced in the Kra

¨

tschmer–Huffman fullerene reactor

(operating at low direct current). A few months after

Iijima’s paper appeared, the first report on the bulk

synthesis of nanotubes, by Ebbesen and Ajayan, was

published. These authors collected the material from

the inner deposit generated by arcing graphite elec-

trodes in inert atmospheres (a similar procedure to

that used for fullerenes).

Nanotubes can be produced by several methods

(e.g., arc discharge, pyrolysis of hydrocarbons over

catalysts, laser vaporization, electrolysis, etc.), with

the products exhibiting various morphologies (e.g.,

straight, curled, hemitoroidal, branched, spiral, hel-

ical, etc.).

It has been predicted that carbon nanotubes may

behave as metallic, semiconducting, or insulating

nanowires depending upon their helicity and diame-

ter. Conductivity measurements on bulk nanotubes,

individual multilayered tubes, and ropes of single-

walled tubules have revealed that their conducting

properties depend strongly on the degree of graph-

itization, helicity, and diameter. Young’s modulus

measurements also show that multilayered nanotubes

are mechanically much stronger than conventional

carbon fibers (Terrones et al. 1999).

The advances typified by fullerenes and related struc-

tures herald a new age in nanoscale materials engineer-

ing. However, this may be only the ‘‘tip of the iceberg’’

since other layered structures (e.g., MoS

2

,WS

2

,VS

2

,

etc.) are also capable of creating closed cages.

See also: Fulleride Superconductors

Bibliography

Dresselhaus M S, Dresselhaus G, Eklund P C 1995 Science

of Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes. Academic Press, San

Diego, CA

Eggen B R, Heggie M I, Jungnickel G, Latham C D, Jones R,

Briddon P R 1996 Autocatalysis during fullerene growth.

Science 272, 87–9

Heath J R, O’Brien S C, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Curl R F, Kroto H

W, Tittel F K, Smalley R E 1985 Lanthanum complexes of

spheroidal carbon shells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 7779–80

Iijima S 1991 Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature

354, 56–8

Kroto H W, Heath J R, O’Brien S C, Curl R F, Smalley R E

1985 C

60

: buckminsterfullerene. Nature 318, 162–3

Kroto H W 1992 C

60

: buckminsterfullerene, the celestial sphere

that fell to earth. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 31, 111–29

Piskoti C, Yarger J, Zettl A 1998 C

36

: a new carbon solid.

Nature 393, 771–4

Rohlfing E A, Cox D M, Kaldor A J 1984 Production and

characterization of supersonic carbon cluster beams. J.

Chem. Phys. 81, 3322–30

Tanigaki K, Prassides K 1995 Conducting and superconducting

properties of alkali-metal C-60 fullerides. J. Mater. Chem. 5,

1515–27

239

Fullerene Formation