Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Terrones H, Mackay A L 1992 The geometry of hypothetical

curved graphite structures. Carbon 30, 1251–60

Terrones H, Terrones M, Hsu W K 1995 Beyond C

60

: graphite

structures for the future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 24, 341–50

Terrones M, Hsu W K, Kroto H W, Walton D R M 1999

Nanotubes: a revolution in materials science and electronics.

Top. Curr. Chem. 199, 189–234

M. Terrones

University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

H. Terrones

Instituto Potosino de investigacio

´

n Cientı

´

fica y

Technolo

´

gica, San Luis Potosı

´

, Mexico

Fulleride Superconductors

The electronic and crystal structures of C

60

lead to a

diverse chemistry based on the intercalation of elect-

ropositive elements into the interstitial sites within

the solid and concomitant transfer of electrons to the

fullerene. This produces solids with partially filled

bands and results in a variety of phenomena includ-

ing superconductivity (Hebard et al. 1991) at the

highest temperatures yet seen for molecular solids.

1. Crystal and Electronic Structures of Solid C

60

For a detailed description of fullerene solids (see

Fullerene Formation). Face-centered cubic solid C

60

(a ¼14.17 A

˚

, r(C

60

–C

60

) ¼10 A

˚

) can to a first ap-

proximation be considered as the cubic close packing

of 5 A

˚

radius hard spheres. Simple radius ratio con-

siderations then allow the calculation of the sizes of

two tetrahedral (T, 1.1 A

˚

) and one octahedral (O,

2.06 A

˚

) interstitial site per C

60

. The extensive inter-

calation chemistry of f.c.c. C

60

derives from the weak

inter-C

60

forces and the size match between the oc-

tahedral and tetrahedral interstitial sites in the f.c.c.

C

60

array and those of the cations of the electro-

positive elements.

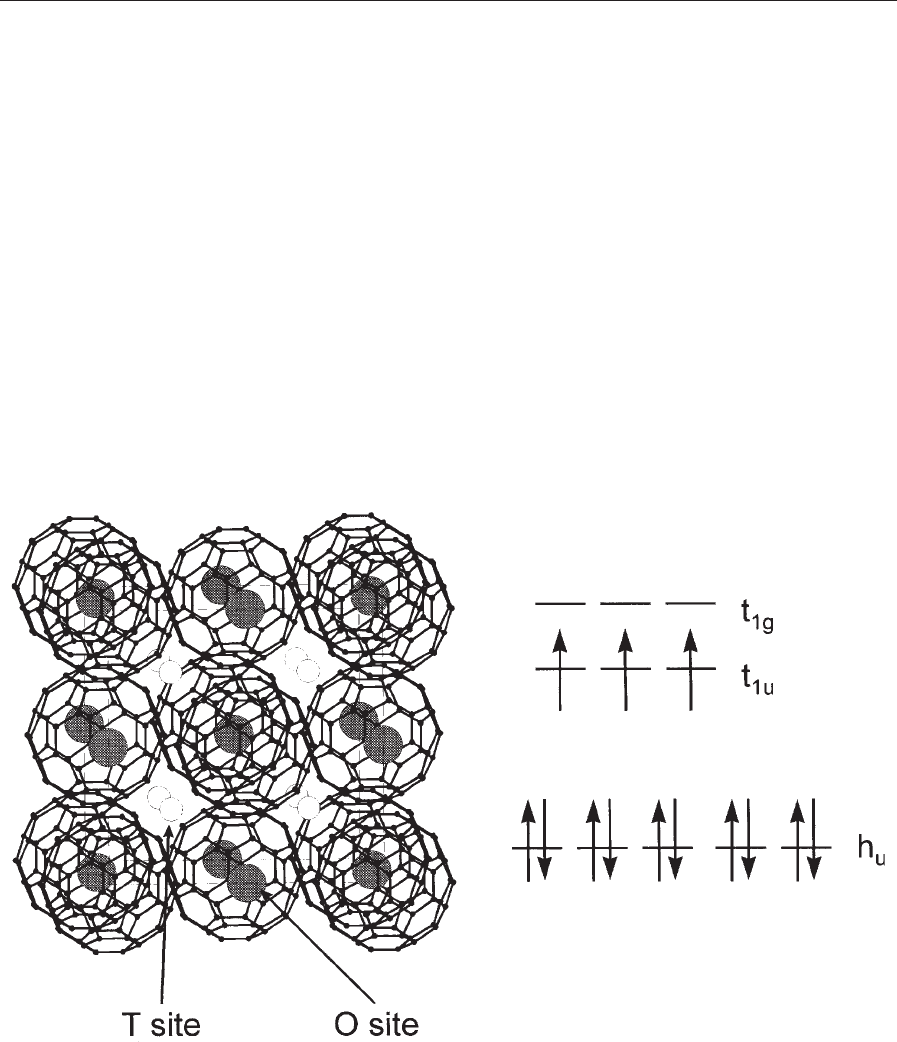

Figure 1

The ordered Fm3 structure of A

3

C

60

(most phases, e.g., K

3

C

60

, have two-fold merohedral disorder of the C

3

60

in space

group Fm3m). Large gray spheres occupy the octahedral (O) site, and small unshaded spheres represent cations on the

tetrahedral (T) sites. Rb

T

2

Cs

O

C

60

is a site-ordered A

3

C

60

phase. A

1

C

60

phases, with only the O sites occupied, are

known with both f.c.c. and polymer structures. Na

2

C

60

results from occupancy of the T sites. Na

4 þx

groups are found

on the O sites in Na

6 þx

C

60

. The frontier orbitals of the C

3

60

anion are shown: the (t

1u

)

3

configuration produces a half-

filled band and metallic behavior in K

3

C

60

.

240

Fulleride Superconductors

The electronic structure of the molecule is important

in determining the properties of the intercalates. The

LUMO of C

60

is almost nonbonding in nature, ac-

counting for the electronegative character of the mol-

ecule, and is triply degenerate with t

1u

symmetry. The

t

1g

‘‘LUMO þ1’’ level is also chemically accessible,

with possible anion charges of up to minus 12 (Fig. 1).

2. Intercalate Structures

2.1 Spherical Counterions

Well-defined structural information exists for sodium,

potassium, rubidium, caesium, calcium, strontium, bar-

ium, europium, samarium, and ytterbium intercalates

(Rosseinsky 1998). An A

1

C

60

rock-salt phase with the

cation occupying the O site alone is formed for A ¼K,

Rb, and Cs and may polymerize by [2 þ2] cycloaddi-

tion on cooling to form a unique air-stable linear-chain

polymer if suitable cooling procedures are followed. A

Pa3symmetryCs

1

C

60

phase is afforded by a particular

cooling sequence. Na

2

C

60

with sodium cations solely

occupying the T sites forms due to the good size match:

there is no analogue of this phase yet known for the

other alkali metals.

The A

3

C

60

phases are formed by complete occu-

pancy of the O and T sites in the f.c.c. structure

(Fig. 1). Cation ordering is observed when size differ-

ences are sufficiently pronounced (e.g., Rb

T

2

Cs

O

C

60

,

Na

T

2

Rb

O

C

60

). Anion orientational order is controlled

by cation size, with the structures of K

3

C

60

(Fm3m)

and Na

2

CsC

60

(Pa3) being related by a 221 rotation of

the anions around the [111] direction. Low-tempera-

ture polymerization is observed in slow-cooled Pa3

Na

2

RbC

60

, with the interfulleride bonding differing

from the A

1

C

60

polymers. Yb

2.75

C

60

has a complex

defect structure based on the A

3

C

60

f.c.c. model, with

vacancy ordering on the O site producing an eight-fold

enlargement of the cell (Ozdas et al. 1995).

Ba

3

C

60

is an A

3

C

60

phase with b.c.c. packing,

adopting the A15 structure of Nb

3

Sn, with the caesi-

um cations ordered over half of the interstitial sites in

the K

6

C

60

structure (Fig. 2(c)). This structure is also

reported for Cs

3

C

60

, where the large Cs

þ

cation forces

a b.c.c. packing on the C

3

60

anions due a size mismatch

with the tetrahedral site in the f.c.c. structure.

Li

3

CsC

60

adopts f.c.c anion packing with an Li

2

Cs

unit on the octahedral site, but most A

4

C

60

phases

adopt the b.c.c. structure of K

4

C

60

.Cs

4

C

60

,Ba

4

C

60

,

and Sr

4

C

60

adopt an orthorhombic distortion of

this structure due to anion orientational ordering

(Fig. 2(b)). Like Ba

3

C

60

, these are also cation vacancy

ordered derivatives of the K

6

C

60

structure. Na

4

C

60

adopts a unique two-dimensional polymerized

structure.

A

6

C

60

phases adopt the b.c.c. packing of K

6

C

60

(Fig. 2(a)) with the cations in distorted tetrahedral

sites. Alkali metal A

6

C

60

salts are electrical insulators

as the (t

1u

)

6

configuration produces a filled band. The

small sodium cation can retain f.c.c. packing in

Na

6

C

60

with Na

4

tetrahedral units on the octahedral

site. This f.c.c. structure is retained up to Na

11

C

60

,

with b.c.c. units on the octahedral site. Ca

5

C

60

is f.c.c.

but with an as-yet undefined superstructure, thought

to be a defect Na

6

C

60

type with similar Ca

4x

units

on the octahedral site.

2.2 Nonspherical Counterions

The above structures are based on packing of near-

spherical objects and all have close analogies in metal

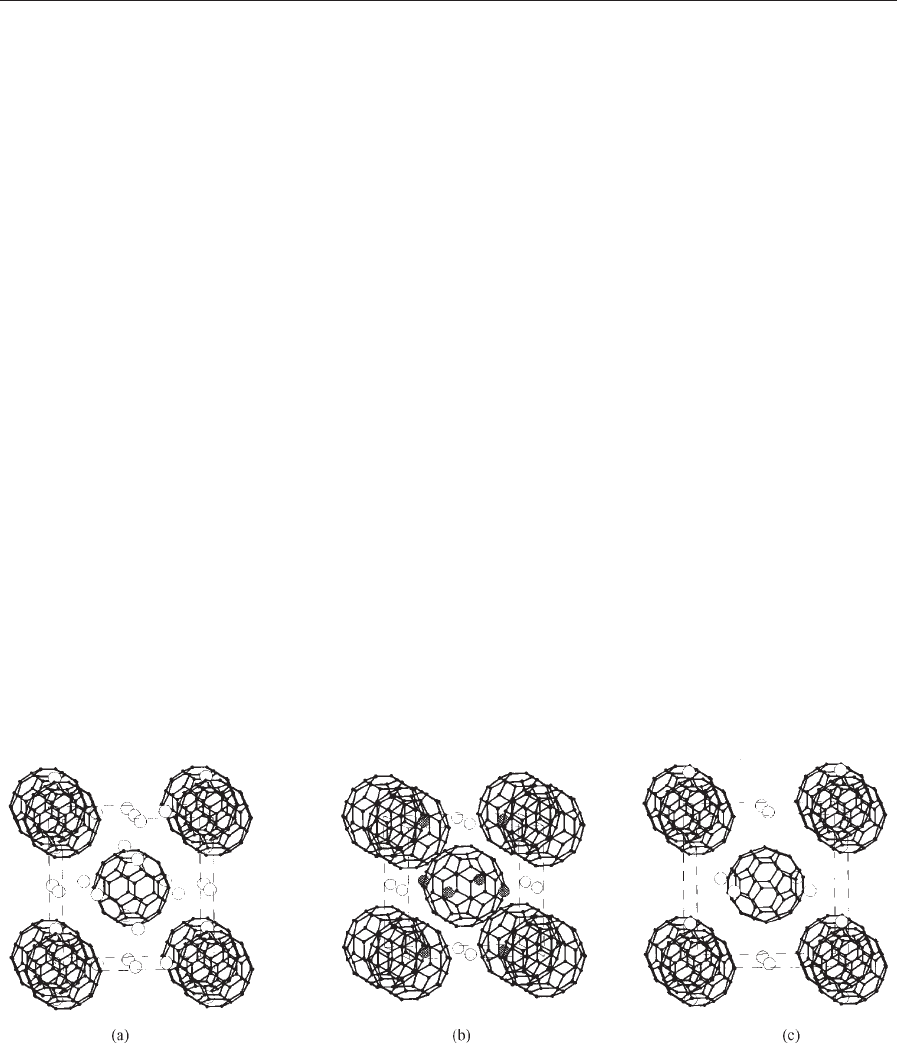

Figure 2

Body-centered fulleride arrays. (a) The Im3 K

6

C

60

structure. The K

þ

cations are in distorted tetrahedral sites. (b) The

A

4

C

60

structure, generated by ordered removal of one-third of the cations from (a). Cs

4

C

60

and the Sr

4

C

60

and Ba

4

C

60

superconductors adopt an orthorhombic Immm structure with orientationally ordered anions, while K

4

C

60

and

Rb

4

C

60

are tetragonal with disordered anions. (c) Ordered occupancy of half of the cation sites in (a) leads to the

Pm3n Ba

3

C

60

structure, in which the fulleride anions at the cell origin and body center adopt orientations related by

901 rotation about the cell vectors.

241

Fulleride Superconductors

and alloy structures. Coordination of a ligand such as

ammonia to the metal ion results in a complex ion

whose size and symmetry are controllable and

generally nonspherical. This results in new structure

types (such as the expanded close-packed (NH

3

)

8

Na

2

C

60

structure), new metal combinations (the

Cs

2

NaC

60

composition is multiphase, but a pure

f.c.c. Cs

2

Na(NH

3

)C

60

phase is accessible with the

linear Na–NH

3

unit oriented in a disordered manner

along with the [111] directions (Iwasa et al. 1997)),

and opportunities to control the electronic properties

of C

3

60

phases in new ways (Rosseinsky 1998). The

reaction of f.c.c. K

3

C

60

with ammonia affords

(NH

3

)K

3

C

3

60

with the NH

3

–K unit on the octahe-

dral site. This lowers the symmetry to orthorhombic,

resulting in the suppression of superconductivity and

a metal–insulator transition at 40 K. Ion-exchange

techniques allow access to transition metal substitut-

ed fullerides such as Ni(NH

3

)

6

C

60

6NH

3

.

3. Superconductivity in Fullerides

The interest in fullerene intercalation chemistry stems

from the discovery of superconductivity at a critical

temperature (T

c

) of 19 K in K

3

C

60

—this transition

temperature was the highest found for a molecular

solid. The interfulleride separation may be tuned by

varying the size of the cations intercalated on the

octahedral and tetrahedral sites, resulting in a mono-

tonic increase in T

c

with lattice parameter (Fig. 3(a)).

This is consistent with T

c

depending on N(E

f

), the

density of states at the Fermi level, in a Bardeen–

Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS)-like manner, as the in-

creased interfulleride separation narrows the width

of the t

1u

band. The same qualitative dependence of T

c

on interfulleride separation is apparent from studies of

the pressure dependence of T

c

of K

3

C

60

and Rb

3

C

60

,

although the quantitative dependence differs slightly.

A range of experiments has clarified the empirical

requirements for fulleride superconductivity. The ob-

servation of superconductivity in orthorhombic

Sr

4

C

60

,Ba

4

C

60

, and Yb

2.75

C

60

demonstrate that nei-

ther cubic symmetry nor a minus 3 fulleride charge is

a prerequisite (Brown et al. 1999). However, T

c

does

appear optimized at an anion charge of minus 3 in the

K

3x

Ba

x

C

60

and Li

2 þx

CsC

60

series. The relative

orientations of the fulleride anions have a drastic ef-

fect on the T

c

(a) relationship—a 221 anion rotation

about the [111] direction converts the Fm3m K

3

C

60

structure into the Pa3 Na

2

CsC

60

structure, resulting

in a much more pronounced T

c

(a) slope. The highest

reported transition temperature in an f.c.c. phase is

33KinCs

2

RbC

60

, while 40 K under 15 kbar pressure

is reported for Cs

3

C

60

, which adopts a body-centered

structure.

The fullerides present a challenge to theory (Gun-

narsson 1997). The sharp peak in T

c

at a minus 3

charge (Fischer 1997) (Fig. 3(b)) has been explained

using the density of states of an orientationally

disordered f.c.c. A

3

C

60

calculated incorporating both

orbital polarization and interelectron repulsion. This is

a BCS-type explanation involving pairing of the t

1u

electrons by phonons. The

13

C isotope effect and the

strong shifting and broadening of the H

(g)

symmetry

vibrational modes in metallic A

3

C

60

compared with

insulating C

60

and A

6

C

60

support this view. Alternative

models point to the inapplicability of a classical BCS

model when the electronic bandwidth (approximately

0.5 eV in A

3

C

60

) is comparable to intramolecular

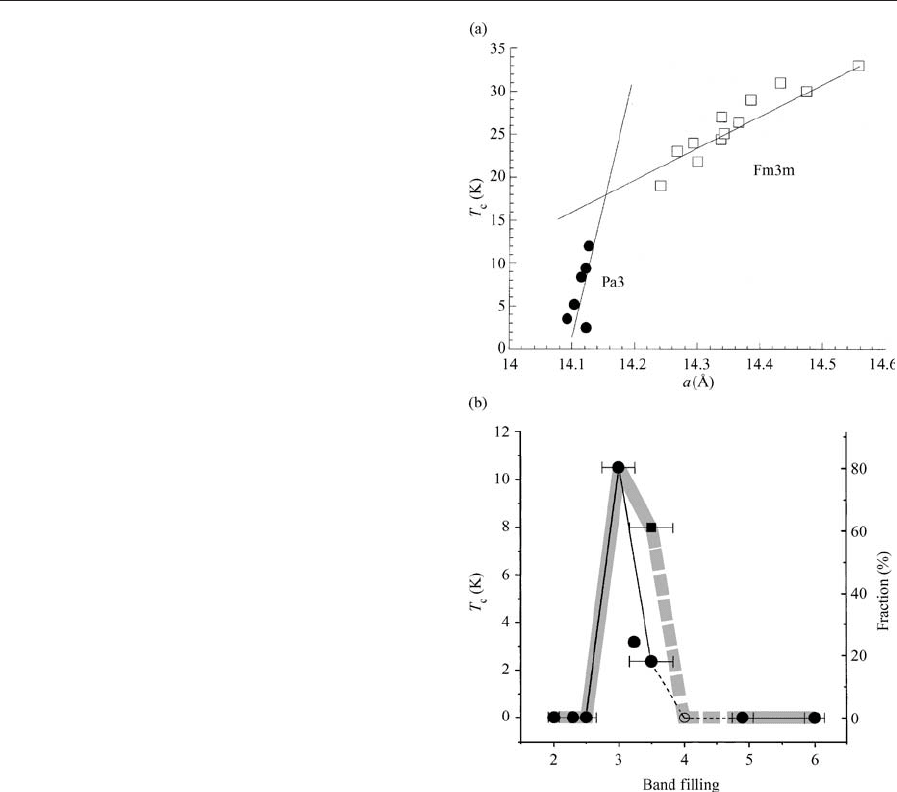

Figure 3

(a) Variation of T

c

with lattice parameter in A

3

C

60

phases. Note the much steeper variation of T

c

with a in

the Pa3 family. (b) Variation of T

c

with charge per C

n

60

anion in the Li

x

CsC

60

series. The open circle is

KBaCsC

60

(reproduced by permission of the American

Physical Society from Phys. Rev. B, 1999, 59, R6628–30).

242

Fulleride Superconductors

phonon frequencies and on-site electron repulsion en-

ergies, and are based on interelectron repulsion be-

tween the t

1u

electrons. These models can reproduce

the isotope effect and the sharp peak in T

c

at the (t

1u

)

3

configuration. Important experimental evidence for the

significance of interelectron repulsion in determining

the electronic ground states of fullerides has come from

the observation of magnetic ordering at the 40 K met-

al–insulator transition of (NH

3

)K

3

C

60

. This phase has

the same volume per C

3

60

but adopts a lower symmetry

structure (2.1.2). Application of pressure suppresses

the magnetic ordering and associated metal–insulator

transition, and restores superconductivity (T

c

¼28 K,

pressure ¼ 15 kbar).

The high superconducting transition temperatures

of the A

3

C

60

phases are not understood, and consid-

erable further experimental and theoretical detail is

required to allow reconciliation between the observed

T

c

and the parameters describing the normal-state

electronic structure deduced from experiment.

Bibliography

Brown C M, Taga S, Gogia B, Kordatos K, Margadonna S,

Prassides K, Iwasa Y, Tanigaki K, Fitch A N, Pattison P

1999 Structural and electronic properties of the noncubic su-

perconducting fullerides A

4

C

60

(A ¼Ba, Sr). Phys. Rev. Lett.

83, 2258–61

Fischer J E 1997 Fulleride solid state chemistry: gospel, heresies

and mysteries. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 58, 1939–47

Gunnarsson O 1997 Superconductivity in fullerides. Rev. Mod.

Phys. 69, 575

Hebard A F, Rosseinsky M J, Haddon R C, Murphy D W,

Glarum S H, Palstra T T M, Ramirez A P, Kortan A R 1991

Superconductivity at 18 K in the potassium doped fullerene

K

x

C

60

. Nature 350, 600–1

Iwasa Y, Shimoda H, Miyamoto Y, Mitani T, Maniwa Y,

Zhou O, Palstra T T M 1997 Structure and superconductivity

in alkali–ammonia complex fullerides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids

58, 1697–705

Kosaka M, Tanigaki K, Prassides K, Margadonna S, Lappas

A, Brown C M, Fitch A N 1999 Superconductivity in

Li

x

CsC

60

fullerides. Phys. Rev. B 59, R6628–30

Ozdas E, Kortan A R, Kopylov N, Ramirez A P, Siegrist T,

Rabe K M, Bair H E, Schuppler S, Citrin P H 1995 Super-

conductivity and cation-vacancy ordering in the rare-earth

fulleride Yb

2.75

C

60

. Nature 375, 126–9

Rosseinsky M J 1998 Recent developments in the chemistry and

physics of metal fullerides. Chem. Mater. 10, 2665

M. J. Rosseinsky

University of Liverpool, UK

243

Fulleride Superconductors

This page intentionally left blank

244

Giant Magnetoresistance

The resistance of a ferromagnetic metal changes when

one applies a magnetic field. This change is related to

the dependence of the resistance on the angle between

the magnetization of the ferromagnet and the electri-

cal current direction, and is called anisotropic

magnetoresistance (AMR) (see Magnetoresistance,

Anisotropic). Although AMR in ferromagnets does

not exceed a few percent at room temperature, it is

used in a number of devices, mainly because the mag-

netization of a soft ferromagnetic material can be

easily manipulated in a low magnetic field. Giant

magnetoresistance (GMR) is another type of magne-

toresistance (MR) which is observed in magnetic

multilayers and is much larger than the AMR of

the ferromagnetic metals. It was discovered in 1988

(Baibich et al. 1988, Binash et al. 1989) on Fe/Cr

multilayers (stack of Fe and Cr layers) and Fe/Cr/Fe

trilayers. In these structures and at zero magnetic

field, the magnetizations of adjacent Fe layers are

oriented in opposite directions by antiferromagnetic

coupling across Cr (Gru

¨

nberg et al. 1986); when an

applied field aligns these magnetizations in parallel,

the resistance of the multilayer decreases dramatically

and this effect has been called giant magnetoresistance

(GMR). The GMR of multilayers is thus associated

with a change of the relative orientation of the mag-

netization in consecutive magnetic layers. Since this

pioneering work on exchange coupled multilayers,

GMR has been observed in a number of magnetic

nanostructures, including uncoupled multilayers, spin

valve structures, multilayered nanowires, and granu-

lar systems (for an extensive review see Barthe

´

le

´

my

et al. 1999). In multilayers, GMR has been observed

either for current in plane (CIP) or with current per-

pendicular to the plane of the layers (CPP geometry).

CPP GMR has revealed interesting spin accumulation

effects which form the basis for further developments.

From the point of view of applications, GMR is

already used in various types of devices such as sen-

sors, read-heads, and magnetic memories (MRAM).

Reading information from a hard disk, for example,

is done in many computers by detecting the resistance

change induced by the small field (about 10

3

T)

generated by the disk. This was achieved with AMR

at the beginning of the 1990s and subsequently with

GMR. While comparable fields can activate both

AMR and GMR devices, the amplitude of GMR is

larger, which permits a reduction of the size

of the information bits and an increase of the den-

sity of stored information to 10–20 gigabitsin

2

(1.6–3.1 gigabitscm

2

).

This article gives an experimental review of GMR.

First, we describe the effects observed in multilayers

(Sect. 1) or spin valve structures (Sect. 2) when the

current flows parallel to the layers. In Sect. 3 the case

where the current flows perpendicular to the layers is

discussed. In Sect. 4 we give a brief phenomenological

overview of the physics of GMR. The theoretical

models for the CIP and CPP geometries are summa-

rized in Sect. 5. Finally, inverse GMR and GMR of

granular structures are presented in Sects. 6 and 7.

1. CIP GMR in Magnetic Multilayers

GMR was first observed in Fe/Cr superlattices

(Baibich et al. 1988) and in Fe/Cr/Fe trilayers

(Binash et al. 1989), in both cases for samples grown

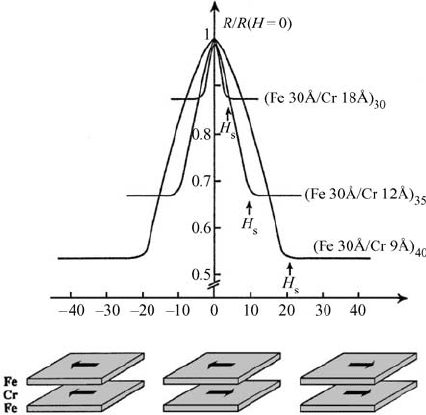

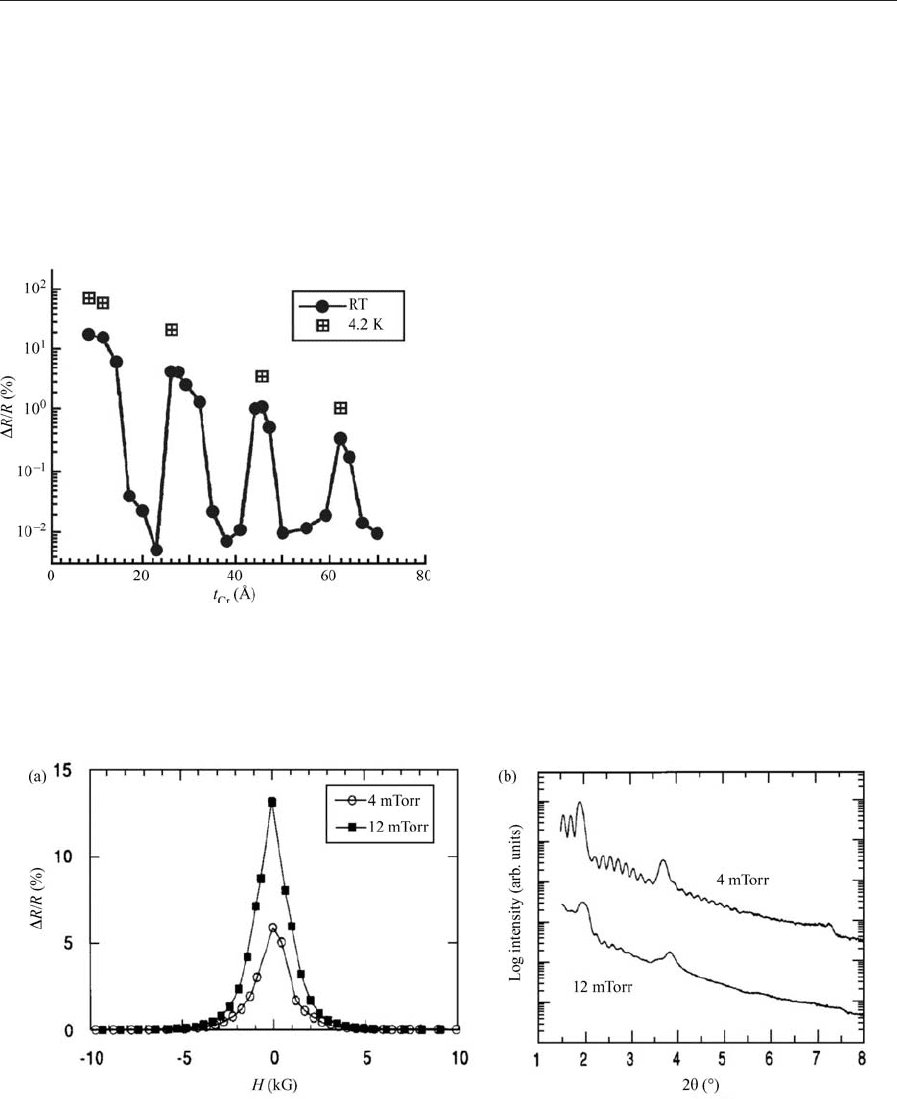

by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Figure 1 shows

the variation of resistance as a function of magnetic

field for Fe/Cr superlattices at 4.2 K. As the magnetic

field increases, the magnetic configuration of neigh-

boring iron layers goes from antiparallel to parallel.

A field H

s

is needed to overcome the antiferro-

magnetic coupling and saturate the magnetization.

Between zero field and H

s

, the resistance drops sig-

nificantly as a result of GMR. The MR ratio is de-

fined as the ratio of the resistivity change to the

resistivity in the parallel configuration. It reaches 79%

at 4.2 K for the sample in Fig. 1 with 9 A

˚

thick chro-

mium layers (and is still 20% at room temperature).

For the Fe/Cr system, the GMR ratio can reach 220%

Figure 1

MR of Fe/Cr multilayers at 4.2 K (after Baibich et al.

1988).

G

245

(Schad et al. 1994), which is well above the AMR ratio

observed in ferromagnetic films (a few %).

Parkin et al. (1990) succeeded in reproducing

similar GMR effects in Fe/Cr, Co/Ru, and Co/Cr

multilayers deposited by sputtering, i.e., with poly-

crystalline samples. Regarding applications, this is of

definite interest as sputtering is a simpler and faster

deposition technique than MBE. In addition, Parkin

et al. (1990) explored details of the dependence of

GMR on spacer layer thickness and found the

oscillatory behavior which reflects the oscillations

of the interlayer exchange coupling. Subsequently, os-

cillations of GMR with the spacer layer thickness have

been found in many systems, as illustrated in Fig. 2 for

the case of Fe/Cr multilayers. As shown in Fig. 2, the

variation of the MR ratio as a function of chromium

thickness presents four well-defined maxima associated

with four ranges of antiferromagnetic (AF) coupling.

In the ranges corresponding to ferromagnetic (F) cou-

pling GMR vanishes. The height of the maximums is a

decreasing function of the chromium thickness. GMR

oscillations have been found in a large number of sys-

tems, but the typical variation illustrated in Fig. 2 is

not always observed. It frequently occurs that, for low

spacer layer thicknesses, the AF exchange coupling is

reduced by F coupling arising from pinholes in the

spacer layer. Indeed, avoiding pinholes is one of the

key challenges in the synthesis of such multilayers.

However, in some cases, the GMR can be restored by

growing discontinuous magnetic layers which, when

broken into small islands, reduce the deleterious effect

of F coupling by pinholes (Duvail et al. 1995).

Not all imperfections are as harmful for GMR as

pinholes through the nonmagnetic layers. Other types

of imperfection, by introducing spin-dependent scat-

tering potentials, can act in the opposite direction and

enhance GMR. For example, introducing cobalt or

iron impurities in nickel layers or dusting permalloy/

Cu interfaces with cobalt can enhance GMR. It has

also been found that, in some cases, GMR can be

enhanced by an increase of the roughness of the in-

terfaces. An example of such an influence of the

roughness of Fe/Cr multilayers on GMR is shown in

Fig. 3.

Figure 2

MR ratio of Fe/Cr multilayers as a function of

chromium layer thickness, t

Cr

, at 4.2 K and 300 K (after

Fullerton et al. 1993).

Figure 3

(a) GMR curves at 4 K for two Fe/Cr superlattices sputtered at different argon pressures. (b) Low-angle x-ray

diffraction spectra of the same samples. The results show that GMR is enhanced by the presence of roughness (after

Fullerton et al. 1992).

246

Giant Magnet oresistance

2. Hard/Soft and Exchange Biased Spin Valve

Structures

GMR requires that an antiparallel configuration of

the magnetizations can be switched into parallel by

applying a magnetic field. AF interlayer exchange

is not the only way to obtain an antiparallel config-

uration. GMR effects can also be obtained with tri-

or multilayers combining hard and soft magnetic

layers (Shinjo and Yamamoto 1990). As the switching

of the magnetizations of the hard and soft magnetic

layers occurs at different fields, there is a field range in

which they are antiparallel and the resistance is high-

er. Such structures are often referred as hard/soft spin

valves. The best-known structure in which interlayer

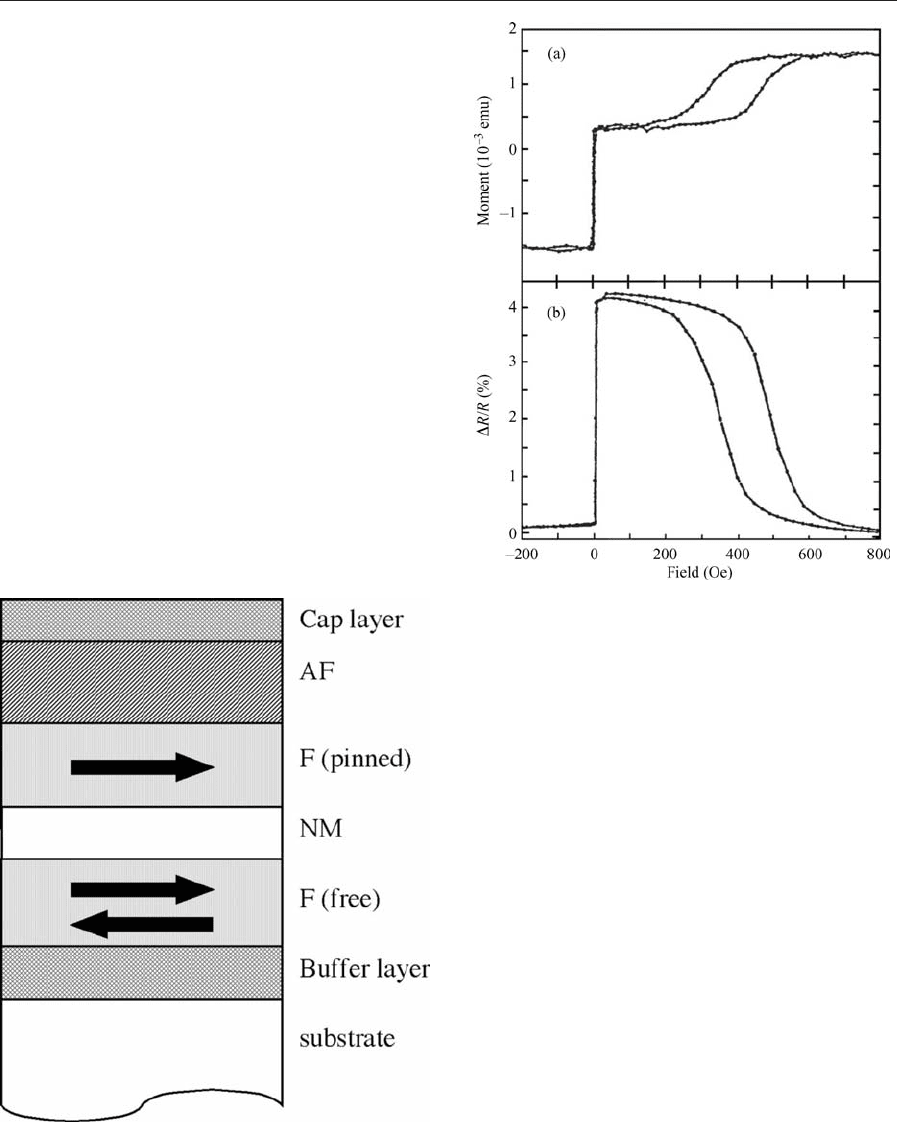

exchange is not used to obtain GMR is the exchange

biased spin valve structure, introduced by Die

´

ny et al.

(1991). As shown in Fig. 4, two soft magnetic layers

are separated by a nonmagnetic (NM) layer, one of

the magnetic layers having its magnetization pinned

by an exchange biasing interaction with an AF pin-

ning layer. The operation of the exchange biased spin

valve can be understood from the magnetization and

MR curves in Fig. 5. One of the permalloy layers has

its magnetization pinned by the AF FeMn layer in the

negative direction. When the magnetic field is swept

from negative to positive values, the magnetization of

the free layer reverses at very small field, whereas the

magnetization of the pinned layer remains fixed in the

negative direction. This gives rise to a steep increase

of resistance. A large positive field is needed to over-

come the exchange biasing interaction and to reverse

the magnetization of the pinned layer, which results in

a drop of the resistance back to its initial value. The

strong and almost reversible resistance variation in a

low-field range makes this structure attractive for ap-

plications such as sensors or read-heads. Since the

mid-1990s, many refinements have been developed to

optimize the performances of exchange biased spin

valve structures.

3. CPP GMR

The discussion of the preceding section concerns meas-

urements performed with the electrical current parallel

to the plane of the layers (CIP geometry). We now

concentrate on GMR effects obtained for CPP geo-

metry (for an extensive review see Bass and Pratt 1999).

Figure 4

Schematic cross-section of an exchange biased spin valve

layered structure.

Figure 5

(a) Hysteresis loop and (b) MR of a spin valve (60 A

˚

NiFe/22 A

˚

Cu/40 A

˚

NiFe/70 A

˚

FeMn) exchange bias

structure at room temperature (after Dieny et al . 1991).

247

Giant Magnet oresistance

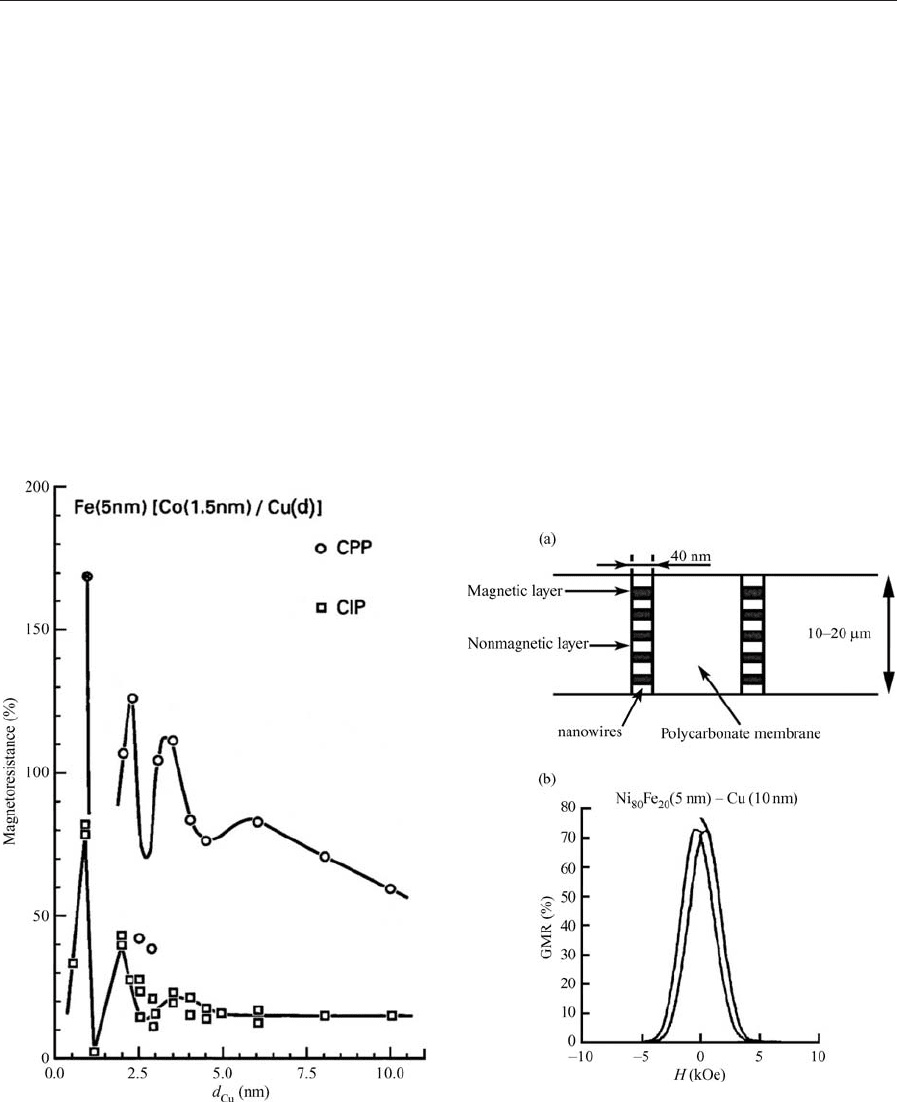

The first measurement in CPP geometry was per-

formed by sandwiching the multilayers between two

superconducting niobium electrodes in a cross-strip

geometry. A comparison between the amplitudes of

CIP GMR and CPP GMR for a series of Co/Cu

multilayers is shown in Fig. 6. It turns out that the

CPP GMR is definitely larger and that the decay as a

function of the spacer layer thickness is weaker in the

CPP geometry.

Several alternative methods without superconduct-

ing contacts have been developed for measurements

of CPP GMR at higher temperatures. Some of these

methods are based on lithography and microfabrica-

tion techniques. Multilayers have been patterned

into pillars using lithography by Gijs et al. (1993).

Although a high-resolution lithography technique

was used in these experiments, the aspect ratios were

not high enough to ensure a pure CPP geometry

without superconducting contacts. Nevertheless, the

first temperature dependence of CPP GMR was ob-

tained with these experiments.

CPP GMR has also been obtained by depositing

multilayers onto grooved InP substrates. An oblique

deposition technique is used, which results in multi-

layers deposited on one face of the groove. Thus, CPP

measurement are achieved when the current flows

perpendicular to the grooves, while, in the same

sample, CIP GMR can be measured by flowing the

current parallel to the grooves (Gijs et al. 1995).

Finally, CPP GMR has also been studied in mul-

tilayered nanowires electrodeposited into the pores of

nuclear track-etched polycarbonate membranes (for

an extensive review see Fert and Piraux 1999). As

illustrated in Fig. 7(a), the aspect ratio of the nano-

wires is very high (of the order of 1000), which guar-

antees that the current is perpendicular to the layers.

However, the number of nanowires connected in

parallel is generally unknown, which restricts the in-

vestigations to the measurements of MR ratios. The

Co/Cu and NiFe/Cu multilayer systems have been

extensively studied in the nanowire geometry. An ex-

ample of experimental CPP GMR result is shown in

Fig. 7(b).

Figure 6

Comparison of CIP and CPP GMR at 4.2 K for a series

of Co (15 A

˚

)/Cu (d

Cu

) multilayers as a function of t

Cu

(after Bass and Pratt 1999).

Figure 7

(a) Schematic representation of multilayered nanowires

electrodeposited in the pores of a polymer matrix. (b)

MR curves at 77 K of NiFe 50 A

˚

/Cu 100 A

˚

multilayered

nanowires (after Fert and Piraux 1999).

248

Giant Magnet oresistance

4. Brief Phenomenological Overview of the

Physics of GMR

GMR is related to the spin dependence of the con-

duction in ferromagnetic metals and alloys (Campbell

and Fert 1982). At low temperature, when the spin

flip scattering of the electrons by magnons is frozen

out, there is conduction in independent parallel chan-

nels by the spin m (majority) and spin k (minority)

electrons. The resistivity of the ferromagnet is then

expressed as:

r ¼

r

m

r

k

r

m

þ r

k

ð1Þ

where r

m

and r

k

are the resistivities of the spin m and

k channels, respectively. The asymmetry between the

two channels can be characterized by the spin asym-

metry coefficient:

b ¼

ðr

k

r

m

Þ

ðr

k

þ r

m

Þ

ð2Þ

There are several origins of the difference between

r

m

and r

k

. First, there is an intrinsic origin, which is

related to the spin dependence of the number, the

effective mass, and the density of states at the Fermi

level of the electrons. There are also extrinsic origins,

which are related to the spin dependence of the im-

purity and defect potentials. In addition, away from

the low-temperature limit, it is necessary to take into

account the transfer of momentum between the two

conduction channels by spin-flip electron–magnon

scattering.

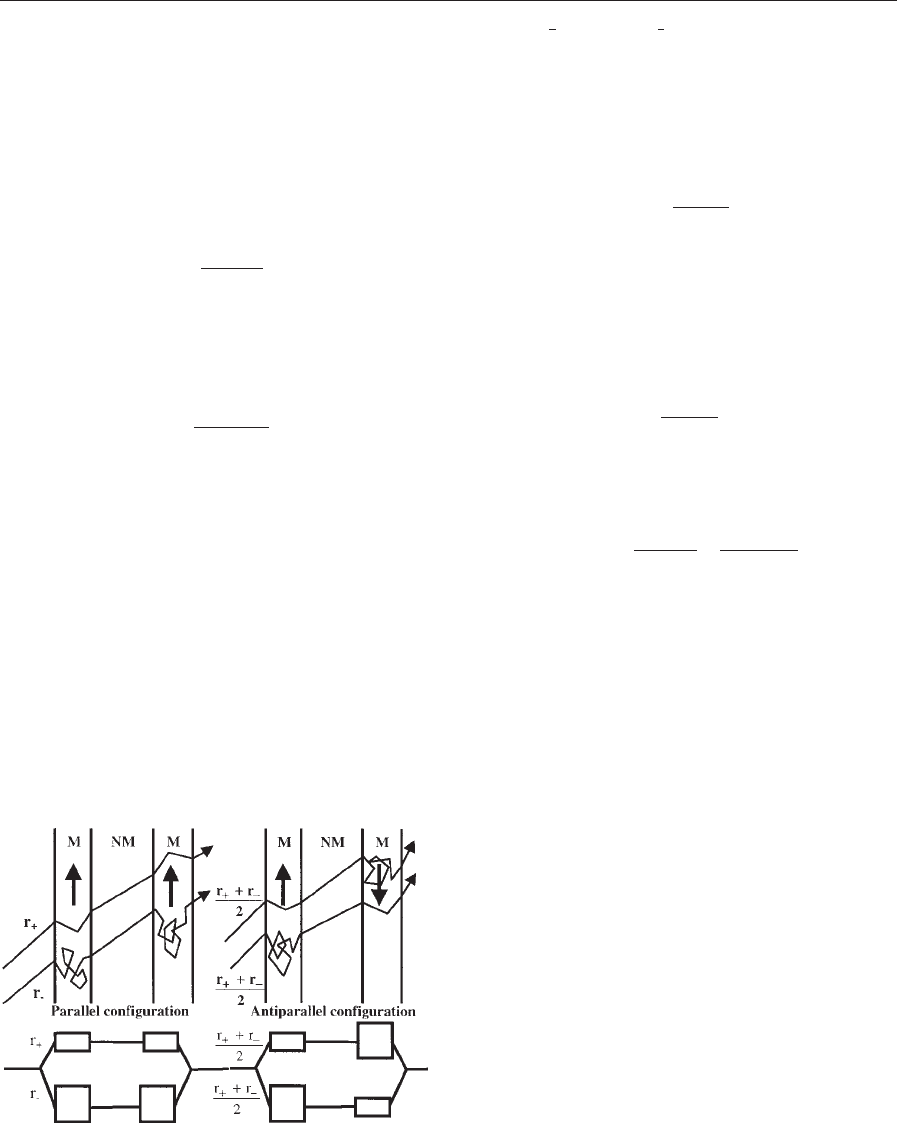

Figure 8 shows schematically the mechanism of

GMR, in the situation where the mean free path

(MFP), l, of electrons is much larger than the period

of the multilayer. Throughout this article, our nota-

tion is þand for the spin directions corresponding

to s

Z

¼þ

1

2

and s

Z

¼

1

2

, z being an absolute axis for

the whole multilayer, and m and k for the majority

and minority spin directions in a given ferromagnetic

layer. In the parallel configuration, the electrons of

the spin þand spin channels are, respectively, ma-

jority and minority electrons in all the magnetic lay-

ers, and this gives different resistances, r

þ

and r

for

the two channels. The final resistance is:

r

P

¼

r

þ

r

r

þ

þ r

ð3Þ

If, for example, r

þ

is much smaller than r

, the

current is shorted by the spin þ channel of fast elec-

trons and r

P

Er

þ

. In the antiparallel configuration,

electrons of both channels are alternatively majority

and minority spin electrons and the shorting by one of

the channels disappears. The resistance is (r

þ

þr

)/2

for both channels and the final resistance is:

r

AP

¼

r

þ

þ r

4

4r

P

ð4Þ

If r

þ

is much smaller than r

then r

AP

Er

/4 is

much larger than r

P

Er

þ

. The general expression for

the GMR ratio is:

GMR ¼

r

AP

r

P

r

P

¼

ðr

r

þ

Þ

2

4r

þ

r

ð5Þ

The above simple picture no longer holds when the

thickness of the layers becomes larger than the elec-

tron MFP (typically 10 nm in nonmagnetic layers, a

few nanometers in ferromagnetic layers), at least for

CIP. For example, when the thickness of the non-

magnetic layers, t

N

, becomes larger than the MFP in

these layers, l

N

, there is no overlap between the re-

spective effects of two consecutive magnetic layers on

the electron distribution function, and the GMR de-

creases as exp(t

N

/l

N

). This is discussed in Sect. 5.1.

In CPP geometry, owing to spin accumulation effects,

the scaling length becomes the spin diffusion length

(SDL), l

sf

, as discussed in Sect. 5.2. The SDL is related

to spin flip scattering and can be much larger than the

MFP which explains that the GMR can be observed

for much thicker layers in the CPP geometry. It is

only when the thickness, t

N

, of the nonmagnetic layers

exceeds the SDL, l

N

sf

, in nonmagnetic materials that

CPP GMR decreases as expðt

N

=l

N

sf

Þ.

5. Models of GMR

The theoretical models of GMR are based on the spin-

dependent conduction described in the preceding sec-

tion. However, predicting the GMR of a multilayer is

difficult because there are various possible origins of

the spin dependence in a given system. This is illus-

trated in Fig. 9, which shows the spin-dependent

potential landscape seen by conduction electrons. One

first sees the intrinsic potential of the multilayers

Figure 8

Schematic representation of the GMR mechanism. The

scheme holds for both CIP and CPP geometries.

249

Giant Magnet oresistance