Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

T4T

B

(unblocked state) the particle susceptibility is

equal to w

0

. For ToT

B

(blocked state), it is given

by w

1

¼ m

0

M

2

s

=3K. Thus, for a broad volume distri-

bution, the susceptibility will be

wðT; t

m

Þ¼

m

0

M

2

s

3kTZ

Z

V

c

0

V

2

f ðVÞdV

þ

m

0

M

2

s

3KZ

Z

N

V

c

Vf ðVÞdV ð16Þ

with V

c

such that T

B

ðV

c

Þ¼T. The fraction of un-

blocked particles decreases with temperature so that

the w versus T curve has a maximum. The

temperature T

max

at maximum is proportional to the

average blocking temperature according to the type

of volume distribution function.

The thermal variation of the initial susceptibility is

commonly studied by measurements at very low field

of the in-phase a.c. susceptibility w

0

ac

ðnÞ¼dM=dH

with n the frequency, and d.c. susceptibility w ¼M/H

(Fig. 2(a)). The d.c. susceptibility measured after

cooling the sample in zero field (ZFC susceptibility)

shows a maximum, like w

0

ac

. The d.c. susceptibility

measured after cooling the sample under field (FC

susceptibility) grows continuously with decreasing

temperature, splitting from the ZFC curve at

T

sp

4T

max

, and finally saturating below some tem-

perature T

sat

. T

sp

and T

sat

correspond to the largest

and smallest T

B

value, respectively. For T4T

sp

, the

system is at equilibrium. For ToT

sp

, it is in a non-

equilibrium state.

In the blocked state, any change of the magnetic

field is followed by a time variation of the magnet-

ization, e.g., both the ZFC and remanent (M

r

) mag-

netizations are time dependent. For a single particle

with relaxation time t

N

(ac1), an exponential time

decay

M

r

ðtÞ¼M

r

ð0Þexp

t

t

N

ð17Þ

was predicted by Ne

´

el. For a volume distribution,

M

r

ðtÞ¼ð1=ZÞ

R

N

0

M

r

ðt; VÞVf ðVÞdV. A decay of the

form M

r

ðtÞ¼A SlnðtÞ is usually found, but devi-

ations can be observed depending on the experimen-

tal conditions (e.g., recording time of the relaxation)

and sample characteristics. The blocked state gives

rise to bulk-like hysteresis cycles, affected by particle

size and anisotropy, responsible for the difference

in saturation, remanence and coercive force H

c

. For

uniaxial anisotropy, when all the moments are

blocked, M

r

¼ M

s

=2 and H

c

¼ H

K

=2 if the easy ax-

es are randomly oriented, and M

r

¼ M

s

and H

c

¼

H

K

if they are aligned parallel to the field. An ori-

entation texture can easily be induced by freezing a

ferrofluid under field.

6. A.c. Susceptibility

The a.c. susceptibility, wðoÞ¼w

0

ðoÞiw

00

ðoÞ,with

o ¼ 2pn the angular frequency, is determined by the

moments able to follow the small a.c. field H ¼ H

0

e

iot

.

Frequencies of interest for ferrofluids range from hertz

to gigahertz, i.e., up to ferromagnetic resonance. For a

uniaxial particle where the moment deviates slightly

from the easy axis, the resonant condition is

o ¼ gm

0

H

K

. Far below resonance, for a random as-

sembly of particles with volume V and relaxation time

t, the particle magnetization is given by

MðtÞ¼H

0

½w

0

ðw

0

w

N

Þe

t=t

ð18Þ

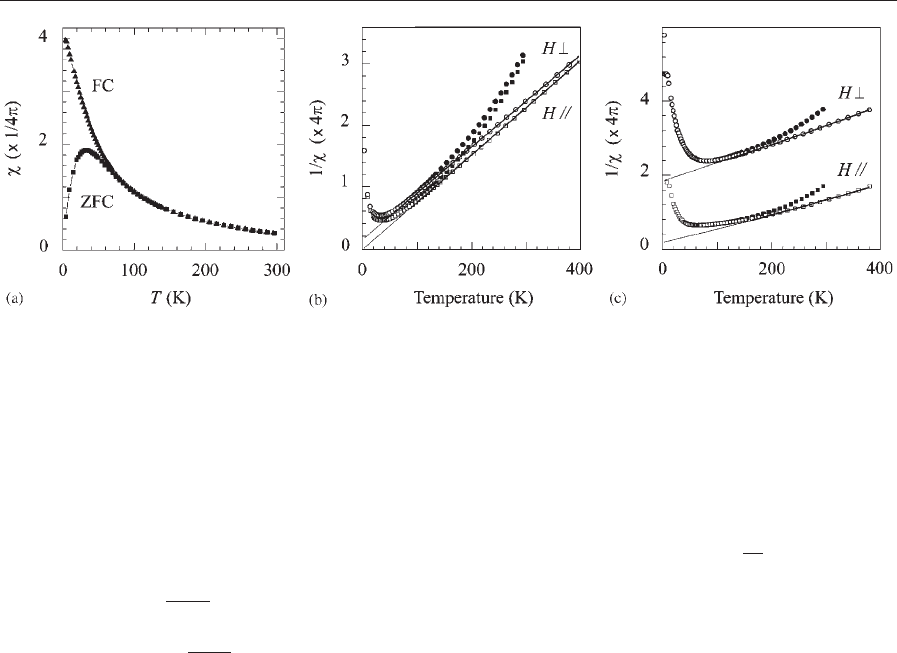

Figure 2

Thermal variation of the initial susceptibility (w) for polymerized g-Fe

2

O

3

ferrofluids. Applied field H ¼800 A m

1

. (a)

Field-cooled (FC) and zero-field-cooled (ZFC) susceptibilities for a dilute sample. (b) Inverse ZFC susceptibility for

parallel or perpendicular geometry; and (c) Concentrated sample. Experimental data (filled symbols); corrected (open

symbols) for the thermal variation of the intrinsic magnetization. Volume fraction of particles (a, b) 0.0075, (c) 0.195.

Average diameter 7.7 nm. (Unpublished data courtesy of M. Nogue

´

s).

200

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

where w

N

is the high-frequency susceptibility. The

Fourier transform gives the susceptibility according to

Debye’s theory

wðoÞ¼

w

0

þ iotw

N

1 þ iot

w

0

ðoÞ¼w

N

þ

w

0

w

N

1 þ o

2

t

2

w

00

ðoÞ¼

ðw

0

w

N

Þot

1 þ o

2

t

2

ð19Þ

w

0

ðoÞ falls monotonically with increasing o, whereas

w

00

ðoÞ has a maximum at ot ¼ 1(Fig.3).Thisenables

one to determine the effective relaxation time and

particle size in a ferrofluid in a relatively simple way.

A single loss peak will be found if the relaxation

time is distributed continuously, in the range

1–100 MHz when the Ne

´

el mechanism dominates,

and much lower when the Brownian process prevails.

For a random assembly of particles, wðoÞ can be de-

scribed in terms of its parallel, w

8

ðoÞ, and perpen-

dicular, w

>

ðoÞ, components according to

wðoÞ¼

w

8

ðoÞþ2w

>

ðoÞ

3

ð20Þ

w

8

ðoÞ and w

>

ðoÞ refer (Eqn. (19)) to longitudinal and

transverse relaxation times, respectively. With in-

creasing frequency, w

8

ðoÞ remains purely relaxational

in character. w

>

ðoÞ is associated with resonance,

which corresponds to w

0

>

ðoÞ going negative. From

the frequency dependence of wðoÞ in the range

100 MHz10 GHz, parameters such as H

K

, K , and

M

r

ðtÞ can be determined.

7. Interparticle Interaction Effects

The magnetic dipolar interparticle interaction always

exists in a particle assembly. In a ferrofluid, its con-

sequences can range from liquid-like short-range

order to highly anisotropic chain configurations as

observed in large applied fields. The energy of particle

i due to interaction with all other particles is given by

E

i

¼m

0

md

X

iaj

H

ij

; H

ij

¼

3ðm

j

dr

ij

Þr

ij

m

j

4pd

3

ij

ð21Þ

where H

ij

is the magnetic field seen by particle i due

to the interaction with particle j, and r

ij

and d

ij

are

the unit vector and distance defining the vector con-

necting the centers of the two particles with moments

m

i

and m

j

. The interaction energy adds to the indi-

vidual anisotropy energy. The particle energies are

interdependent and the whole system tends to min-

imize its magnetostatic energy. A ferrofluid system,

unconstrained topologically, will partition itself into

an ensemble of subsystems with low magnetostatic

energy.

Relaxation in the particles can be assumed blocked

and the leading parameter is l ¼ m

0

m

2

=4pD

3

h

kT with

D

h

the hydrodynamic particle diameter, neglecting

size distribution. The stability of the suspension of

particles limits the value of l. No spatial correlation

occurs if lt1. Clustering develops with growing l

and when l is large enough, all particles are aggre-

gated at equilibrium, as shown by Monte Carlo

simulations. Short linear chains (dimers, trimers)

predominate at small l values. Bending and branch-

ing appear when l increases. At medium values,

closed magnetic configurations prevail. For large l

values, the cluster structure is more and more iso-

tropic and dense, with the orientation of the mo-

ments tending to be randomized. In large applied

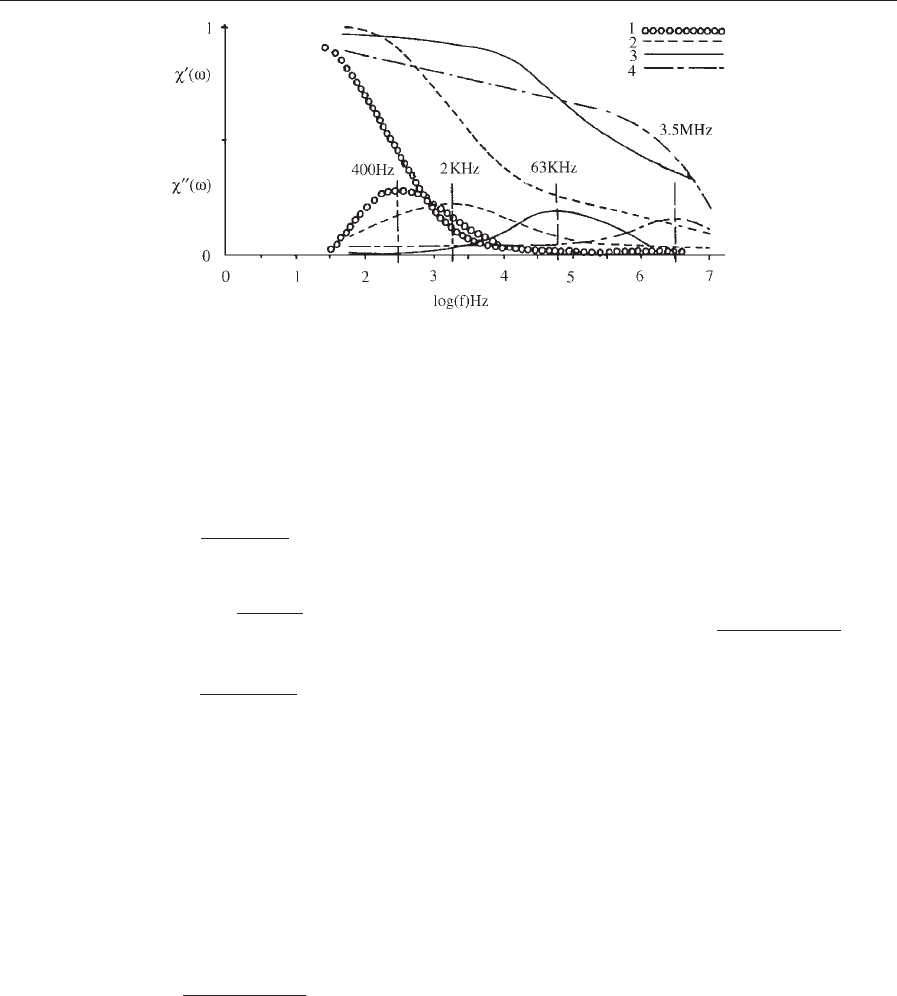

Figure 3

Normalized plots of the real and imaginary parts of the a.c. susceptibility against frequency for cobalt ferrite (1,3) and

magnetite (2,4) ferrofluids. Median particle radius of (1–3) 5 nm, (4) 4.5 nm. (Reprinted with permission from Fannin

1994; r Elsevier Science B.V.)

201

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

fields, the spatial order becomes anisotropic. The

orientation effect of the field strengthens the interac-

tions favoring chain-like configurations, which give

rise to the anisotropic magneto-optical properties of

ferrofluids.

The interactions influence the magnetic properties

especially in low applied fields. They cause deviations

from the Langevin behavior (Figs. 2(b) and (c)). The

equilibrium magnetization is given by the Langevin

law, referring to the effective field, H

eff

, seen by the

particle, which is not equal to the applied field, H

app

,

in the presence of interaction. Since the sample is

magnetized, boundary phenomena give rise to de-

magnetizing field effects. The demagnetizing field is

constant inside the sample if this is an ellipsoid with

an axis parallel to the applied field. The field exterior

to the particles is then given by

H

ext

¼ H

app

N

e

C

v

M ð22Þ

with N

e

(0pN

e

p1) the demagnetizing factor of the

sample. The measured susceptibility w

app

¼ M=H

app

depends on the geometrical experimental parameters,

unlike w

ext

¼ M=H

ext

.

Different models have been proposed for estimat-

ing H

eff

as a function of H

ext

. They all lead to first

order, with a varying range of applicability, to the

same formula for the initial susceptibility

w

ext

¼ w

0

ð1 þ N

i

C

v

w

0

Þð23Þ

where N

i

¼ 1=3. This agrees with experimental re-

sults, after correcting for size distribution and ther-

mal variations of M

s

and C

v

, and with numerical

simulations for w

n

0

¼ C

v

w

0

t3. In the limit w

n

0

{3, the

susceptibility takes a Curie–Weiss form; it is in no

way indicative of a magnetic phase transition. For

w

n

0

\3, correlations cannot be neglected and Eqn. (23)

does not hold; the influence of the microstructure

ðw

n

0

E8lC

v

Þ no longer reduces to a concentration ef-

fect and Monte Carlo simulations are in practice the

only reliable way of modeling. Since the texture varies

with field and temperature (l), the magnetic behavior

of ferrofluids can be extremely complex. In real sys-

tems, clustering of physicochemical origin may bring

extra complexity.

The interactions affect the Brownian dynamics

(Fig. 3), especially because a cluster is a rotating

Brownian object, with relaxation time proportional

to the volume. They modify the dynamics in the par-

ticles depending on the topology and relative mag-

nitudes of the anisotropy and interaction energies. In

random solid systems, for weak enough interactions,

the dynamics can still be described in the framework

of the Ne

´

el relaxation. The interactions increase the

energy barrier. In the Dormann et al. (1997) model,

valid when all (most) moments are above or near

their blocking temperature, the increase for particle i

is approximately given by

E

Bint

ðiÞ¼

X

j

q

ij

L

q

ij

kT

; q

ij

¼

m

0

4p

m

i

m

j

3cos

2

x

ij

1

d

3

ij

ð24Þ

where x

ij

is an angle parameter of r

ij

. For strong

enough interactions, the behavior will become co-

operative in type. In any case, typical features (e.g.,

aging effect on the magnetization relaxation) of cor-

related disordered systems, such as spin–glass sys-

tems, will be observed if the experimental conditions

(temperature, time window) are suitably chosen. In

ferrofluids, the dynamics in aggregated particles in-

fluences the lifetime of their association.

8. Summary

The theoretical models of magnetic dynamics in

ferrofluids and main macroscopic experimental fea-

tures have been outlined. The main difference be-

tween Ne

´

el and Brownian relaxations lies in their

timescales. It is the key to the specific properties of

ferrofluids, i.e., a perfectly soft behavior (irrespective

of particle size, concentration, and aggregation), an

orientational texture under field, and a spatial texture

caused by the magnetic interparticle interaction.

See also : Ferrofluids: Applications; Ferrofluids: In-

troduction; Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies;

Ferrofluids: Preparation and Physical Properties;

Ferrohydrodynamics

Bibliography

Brown F J Jr. 1979 Thermal fluctuations of fine ferromagnetic

particles. IEEE Trans. Magn. Mag-15, 11961–208

Chantrell R W, Walmsley N, Gore J, Maylin M 2000 Calcu-

lations of the susceptibility of interacting superparamagnetic

particles. Phys. Rev. B63, 024410

Coffey W T, Cregg P J, Kalmykov Yu P 1993 On the theory of

Debye and Ne

´

el relaxation of single domain ferromagnetic

particles. In: Prigogine I, Rice S A (eds.) Advances in Chem-

istry and Physics. Wiley, New York, Vol. 83

Coffey W T, Crothers D S F, Dormann J L, Geoghegan L J,

Kennedy E C 1998 Effect of an oblique magnetic field on the

superparamagnetic relaxation time. Phys. Rev. B58, 3249–66

Coverdale G N, Chantrell R W, Martin G A R, Bradbury A,

Hart A, Parker D A 1998 Cluster analysis of the microstruc-

ture of colloidal dispersions using the maximum entropy

technique. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 188, 41–51

Dormann J L, Fiorani D, Tronc E 1997 Magnetic relaxation in

fine-particle systems. In: Prigogine I, Rice S A (eds.) Ad-

vances in Chemistry and Physics. Wiley, New York, Vol. 98

Dunlop D J, O

¨

zdemir O

¨

1997 Rock Magnetism. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge

Fannin P C 1998 Wideband measurement and analysis tech-

niques for the determination of the frequency-dependent,

complex susceptibility of magnetic fluids. In: Prigogine I,

Rice S A (eds.) Advances in Chemistry and Physics. Wiley,

New York, Vol. 104

202

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

Kodama R H 1999 Magnetic nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 200, 359–72

Pshenichnikov A F, Mekhonoshin V V 2000 Equilibrium mag-

netization and microstructure of the system of super-

paramagnetic interacting particles: numerical simulation. J.

Magn. Magn. Mater. 213, 357–69

Raikher Yu L, Stepanov V I 1997 Linear and cubic dynamic

susceptibilities of superparamagnetic fine particles. Phys.

Rev. B55, 15005–17

E. Tronc

C.N.R.S., Universite

´

Pierre et Marie Curie

Paris, France

D. Fiorani

Institute of Materials Chemistry, C.N.R., Rome, Italy

Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies

The investigation of the internal structure of mag-

netic fluids is often carried out by indirect techniques

like magnetization measurement or ex situ investiga-

tions, e.g., the electron micrography of specially pre-

pared fluid samples. This causes strict limitations

concerning the interpretation of the fluid microstruc-

ture itself as well as of the dependence of macroscopic

properties of the fluids on microscopic structural

changes.

A possibility to overcome these restrictions is the

use of neutron scattering to explore microstructural

properties of magnetic fluids. In contrast to normal

light, scattering neutrons are able to penetrate ferro-

fluid samples of reasonable thickness and to give ap-

propriate scattering intensities on experimentally

practicable time scales. The intensity of neutrons scat-

tered by a ferrofluid contains an additional anisotrop-

ic magnetic part besides the usual nuclear scattering.

This magnetic part of the scattering intensity I

m

de-

pends on the relative orientation between the scatter-

ing vector q

!

, the neutron polarization p

!

, and the

magnetization of the fluid sample m

!

respectively:

I

m

pfð q

!

p

!

Þðq

!

m

!

Þg

2

ð1Þ

If unpolarized neutrons are used—and thus the

first bracket becomes a constant factor—the scatter-

ing intensity of magnetic scattering is anisotropic de-

pending on the relative orientation between scattering

vector and sample magnetization:

q

!

m

!

2

¼

0if q

!

8m

!

1if q

!

>m

!

8

>

<

>

:

9

>

=

>

;

ð2Þ

For an unmagnetized sample the ð q

!

m

!

Þ

2

-term

equals 2=3 and the scattering becomes isotropic as it

can be seen from Fig. 1. In particular, magnetic neu-

tron scattering allows direct access to the magnetic

microstructure and thus to the solutions of questions

like magnetic size distribution or cluster and chain

formation of magnetic particles. Details concerning

the possibility to distinguish between nuclear and

magnetic scattering will be discussed in the forth-

coming sections.

1. Selection of Experimental Method

The choice of the particular neutron scattering method

to be used is determined by the size of the scattering

units and the main goal of the investigation itself.

The typical particle size range for the particles sus-

pended in a magnetic fluid—which is usually between

5 nm and 30 nm—requires a range of q-vectors to be

examined between:

q

min

¼

2p

d

max

E0:2

(

A

1

and

q

max

¼

2p

d

min

E1

(

A

1

ð3Þ

For thermal neutrons with a wavelength l of about

6A

˚

to 10A

˚

, which are usually used for the experi-

ments, this corresponds to scattering angles y defined

by

sinðyÞ¼

lq

4p

ð4Þ

in the range between 51 and 251. That means that the

method usually chosen for ferrofluid investigations is

small angle neutron scattering (SANS). For details on

SANS experiments the reader should refer to the basic

textbooks by Guinier (1963) and Egelstaff (1965).

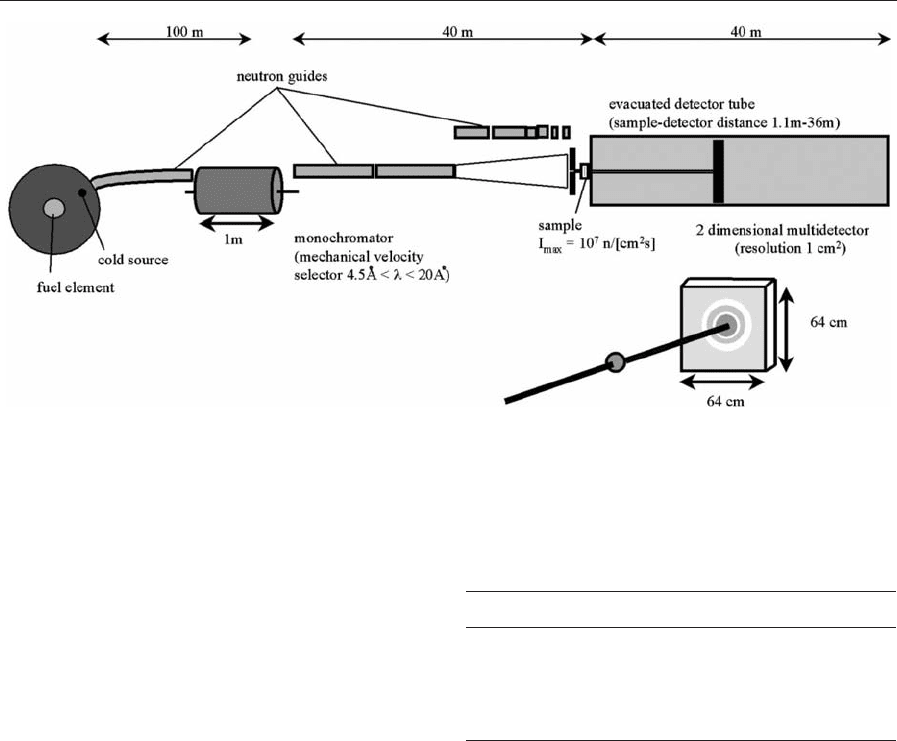

Figure 2 shows the principal set up for a SANS ex-

periment with magnetic fluids. The sample is subjected

to a collimated neutron beam transmitted through

the fluid. The scattered neutrons are usually detected

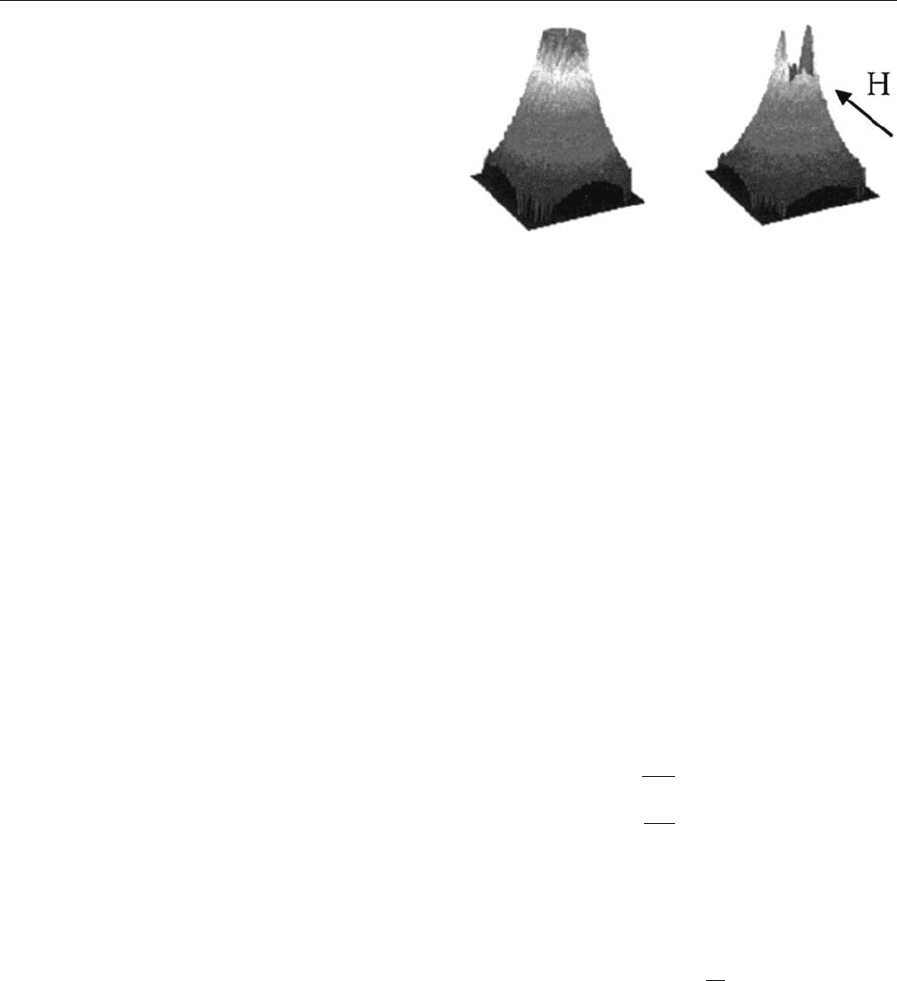

Figure 1

Typical small angle scattering signal from an

unmagnetized ferrofluid (left) and from a fluid under

influence of a field H in the depicted direction (right)

(after Odenbach 2000).

203

Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies

using a two-dimensional array detector. The detec-

tor—sample distance can be altered to vary the max-

imum momentum transfer detectable. To avoid

reduction of scattering intensity, the neutron path to

the sample and from the sample to the detector is

guided through vacuum tubes.

SANS experiments can be carried out using polar-

ized as well as unpolarized neutrons, providing dif-

ferent kind of information, as can be seen from Eqn.

(1). Some basic experimental questions will be dis-

cussed, followed by the experiments with unpolarized

neutrons that represent the major amount of exper-

imental work performed. Finally, experiments with

polarized neutrons and other experimental tech-

niques will be outlined.

2. Nuclear Scattering and Contrast Variation

As was already mentioned, neutron scattering on

magnetizable materials provides an anisotropic part

of scattering intensity as a result of the interaction

between the neutrons magnetic moment and the

magnetization of the sample.

Besides this, the most important part of scattering

intensity will usually be made by conventional nuclear

scattering. The total cross-section for nuclear scatter-

ing is composed from the coherent s

coh

, incoherent

s

inc

, and absorption s

abs

scattering cross-sections of

the particles material, the surfactant, and the solvent.

The scattering cross-sections for the most important

elements contained in a ferrofluid are given in Table 1.

Essential for scattering experiments is the relation

between the coherent scattering providing the signal

and incoherent scattering and absorption leading to

unwanted noise and signal reduction. For the metallic

particles the coherent scattering cross-section is dom-

inant compared to the incoherent part and only weak

absorption occurs leading to only small reduction of

the scattered intensity. For surfactant and carrier

liquid, one has to distinguish between deuterated and

nondeuterated material. If nondeuterated substances

are used, the scattering behavior will be dominated by

the incoherent scattering due to the hydrogen atoms.

In this case the scattering from the surfactant and the

carrier liquid will dominate the incoherent scattering

of the whole sample investigated. The scattering from

the particles will be just a small additional part over a

strong incoherent noise and thus detection may be

difficult. Furthermore, the maximum thickness of the

sample in the direction of the beam will be reduced

Figure 2

A typical SANS scattering geometry at the example of the small angle scattering instrument D11 at the Institute Laue

Langevin in Grenoble.

Table 1

Scattering cross-sections for relevant elements in barns.

Element s

coh

s

inc

s

abs

Fe 1.86 0.46 1.4

H 1.76 79.7 0.19

D 5.59 2.01 5 10

4

O 4.23 0.01 1 10

4

C 4.52 0.98 3 10

3

Source: Egelstaff (1965).

204

Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies

due to the incoherent scattering by hydrogen. Exper-

iments (Odenbach et al. 2000) have shown that the

scattering intensity rises by a factor of approximately

three if deuterated carrier liquids are used and the

necessary counting time for a given sample thickness

and for reasonable statistics can be furthermore re-

duced due to the improvement of the signal/noise

ratio in the case of absence of hydrogen.

Beside this, the partial replacement of hydrogen by

deuterium allows special experimental approaches

providing additional information about the ferrofluid

sample. If one defines the excess scattering from the

particles over the scattering from the carrier liquid as

the scattering contrast (Cebula et al. 1983b), one can

change the scattering intensity by variation of the

scattering from carrier liquid and surfactant. The

optimization of the contrast between particles and

carrier solvent provides optimum statistics of the sig-

nal and ensures that the scattered signal is dominated

by the internal particle structure of the ferrofluid. By

comparison of scattering intensities from a fluid with

deuterated surfactant with that from one having con-

ventional surfactant, information about the thickness

of the surfactant layer can be obtained. The best way

to do that is the use of a Guinier plot, i.e., a plot of

the logarithm of scattered intensity over the square

of q. This plot provides a linear relation for small

q-vectors with a slope proportional to the mean size

of the scattering units. Thus in the first case a Guinier

plot provides the core size of the particles, in the sec-

ond case it reflects the size including the surfactant.

3. SANS Experiments for Determination of Size

Distribution

Size distribution determination for the particles in a

magnetic fluid can be done by electron microscopy or

magnetic measurement. In the first case a sample

must be prepared by a process that may modify the

size distribution, while the second method provides

values that strictly depend on the underlying mag-

netic theory, in particular the question of interaction

between the particles can cause serious problems.

From Eqns. (3) and (4) it is seen that the scattering

angle depends on the size of the scattering structures,

i.e., in the case of a ferrofluid on the size of the

particles

sinðyÞ¼

l

2d

ð5Þ

A monodisperse colloid would provide a SANS

signal which would directly allow the determination

of the particle size from a Guinier plot. For a poly-

disperse system the situation becomes more difficult,

since multiple signal structures are superimposed.

Under these conditions a model is needed to fit the

data and to obtain the size distribution. Most often

the usual log normal distribution is used as base

model for the fits, but newly developed fitting soft-

ware at several neutron sources allows more model-

independent determination of the distribution. The

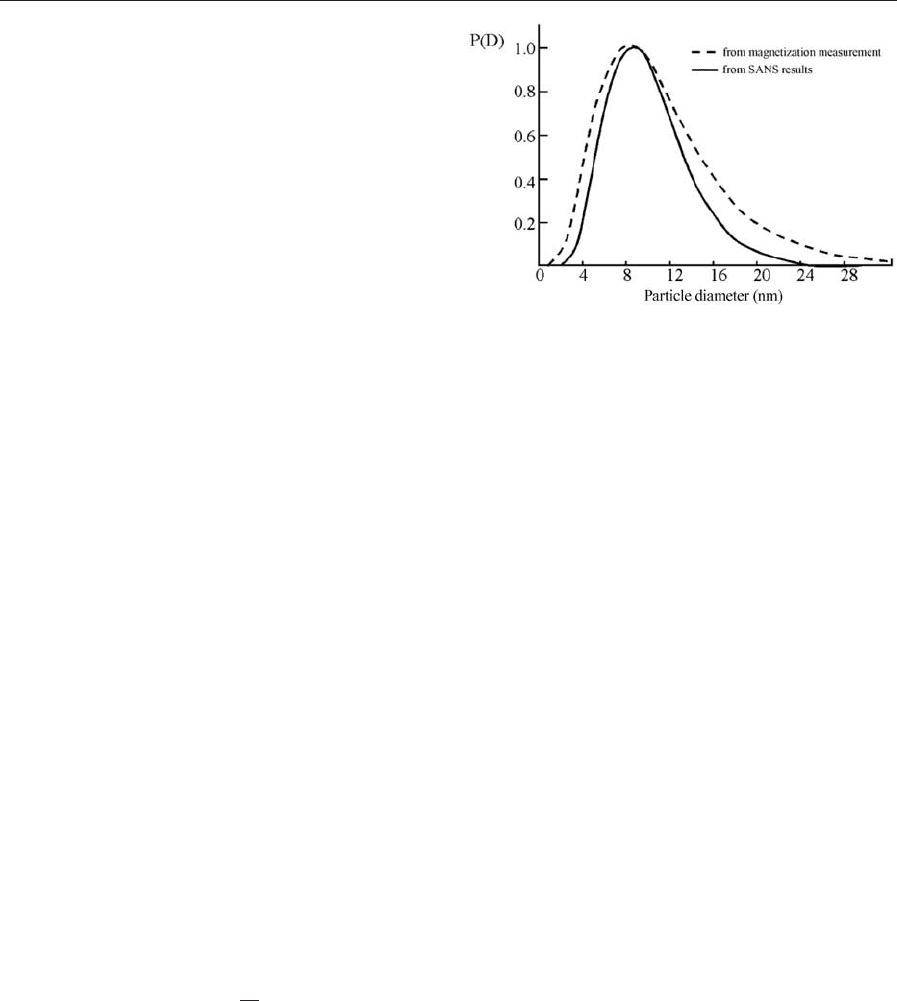

experimental results obtained in SANS studies show

various deviations from the distributions determined

with conventional methods like magnetization meas-

urement that shed a light on some basic problems in

the understanding of magnetic fluids. In some exper-

iments (e.g., Potton et al. 1983) an expansion of the

size distribution to larger radii was obtained from the

SANS data compared to magnetization measure-

ment, while Upadhyay et al. (1993) observed a nar-

rower distribution in neutron experiments (Fig. 3).

The explanations for these discrepancies are usu-

ally taken from the lack of knowledge about basic

data of the fluids themselves. While the narrower

distribution is explained by field-induced magnetic

interaction between the particles in magnetization

measurement, not accounted for in the data evalua-

tion of these measurements, the expansion to larger

radii could be explained by the difference between the

bulk saturation magnetization and that of small par-

ticles (So

¨

ffge et al. 1981). Furthermore, the assump-

tion of spherical particles which is usually used when

fitting the neutron data together with the consider-

ably large errors of neutron scattering data in general

could also lead to discrepancies. Thus it is seen that

the underlying model for the data evaluation and the

assumptions within as well as the accuracy of the data

obtained are of significant influence on the results

obtained. While the models used can only be im-

proved on the basis of new experimental results, the

quality of the scattering data must be optimized

Figure 3

The comparison between particle size distributions

measured with conventional magnetization

measurement and by SANS. The discrepancy is

explained by the neglection of field-induced interaction

of the particles in magnetization measurement analysis

(after Upadhyay et al. 1993).

205

Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies

(e.g., by appropriate choice of deuterated carrier liq-

uids) to avoid additional uncertainties.

4. SANS Experiments for Observation of Cluster

Formation

While SANS methods are only an alternative in de-

termining particle size distribution, they provide a

unique tool if the formation and development of

clusters and cluster like structures of magnetic par-

ticles are considered. Aggregation of particles forms

structures—determining the scattering process—

which have sizes in the order of several hundred

nm. Thus the intensity scattered by these structures

will be found at even smaller scattering angles of the

order of 11 and less. Even the best small angle scat-

tering experiments available nowadays reach with

such requirements the edge of their technological

possibilities. Nevertheless the influence of the scat-

tering from large structures changes the line shape of

the small angle scattering signal even at higher angles

easily available in experiments. Such changes can

then be taken to obtain information on formation of

multiparticle aggregates in magnetic fluids.

In this way, Cebula et al. (1983a) investigated the

appearance of cluster formation in ferrofluids con-

taining cobalt particles. They found a strong depend-

ence of the scattering signal on the volume fraction

of particles at zero field indicating the appearance

of cluster formation due to magnetic dipole—dipole

interaction. Furthermore, they found interference

peaks when a magnetic field was applied, indicating

the appearance of ordered structures like chains

aligned with the magnetic field direction. Finally re-

duction of temperature, resulting in a reduction of

thermal motion, lead to an anisotropy at H ¼0, also

indicating formation of aggregates and chains. Thus

these experiments showed clearly that SANS is a

powerful tool for the in situ observation of aggrega-

tion phenomena in ferrofluids without disturbing ef-

fects due to drying in sample preparation for electron

micrography.

Extended work on aggregation formation in mag-

netite-based ferrofluids was carried out by Rosman

et al. (1990). They combined the SANS measure-

ment in variable magnetic fields with the already

discussed contrast variation method providing them

with the particle size distribution and the structure

of the surfactant layer of the fluids under investiga-

tion. Here again the mentioned differences between

conventional and neutron scattering methods ap-

peared. Even at low volume fraction and in compa-

rably weak magnetic fields of about 100 mT they

found a formation of thin chains of particles in the

direction of the applied field. Higher volume con-

centration enabled formation of three-dimensional

rods in field direction. The interparticle distance

obtained from the scattering data gave rise to the

assumption that the surfactant layers are in contact

in the aggregates.

Even larger structures can be observed in ferrofluid

mixtures (Hayter et al. 1989) when macromolecules

are dispersed in a ferrofluid. These nonmagnetic mol-

ecules act as magnetic voids in the liquid and arrange

to macroscopic structures in presence of magnetic

fields. The neutron diffraction patterns obtained

show an anisotropy that corresponds to these mac-

rostructures. In this case the neutron diffraction ex-

periments were used to prove the possibility of

alignment of nonmagnetic macromolecules by means

of magnetic fluids.

5. SANS Experiments with Polarized Neutrons

During the discussion of neutron scattering data ob-

tained from ferrofluids with unpolarized neutrons, it

became clear that anisotropies in the scattering pat-

tern can be due to magnetic effects (see Eqn. (1)) as

well as due to formation of structures. The use of

polarized neutrons can be a powerful help to distin-

guish between these two kind of anisotropies and

thus to eliminate the nuclear scattering background

completely. To do so the fluid sample is subjected to a

beam of polarized neutrons and a polarization anal-

ysis—distinguishing between neutrons scattered with

spin flip and those scattered without—is carried out

after the scattering process. Coherent nuclear scat-

tering, giving information about the structural phe-

nomena like aggregation by measuring the particle

number density, does not flip the neutrons spin. In

contrast, the magnetic scattering—which is caused by

the component of magnetization perpendicular to

q

!

—causes spin flip for those components of mag-

netization which are perpendicular to the field, while

the parallel one gives nonflip scattering. Therefore

measurement of scattered intensity with q

!

parallel

and perpendicular to the applied field makes it pos-

sible to distinguish between nuclear and magnetic

scattering signals. This technique has been used by

Pynn et al. (1983) to analyze the interparticle struc-

ture in a cobalt ferrofluid.

The previously discussed problem of the influence

of polydispersity on the SANS signal can also be re-

duced by the use of polarized neutrons (Nunes 1988).

Furthermore, a detailed analysis of nuclear and mag-

netic scattering intensities and of the respective size

distributions obtained can shed a light on the exist-

ence of magnetically dead layers.

6. Other Experimental Approaches

Up to now we have outlined the use of neutron scat-

tering for determination of structure and agglomera-

tion processes in magnetic fluids using SANS

techniques. Beside this, there are a couple of experi-

ments taking neutron scattering for other experimental

206

Ferrofluids: Neutron Scattering Studies

goals or using alternative scattering techniques. For

example SANS experiments have been used to inves-

tigate diffusion phenomena in magnetic fluids (Oden-

bach et al. 1995) by determination of the spatial

variation of magnetic scattering anisotropy. Since the

anisotropy is proportional to magnetization of the

fluid and since this is a measure for the concentration

of particles at given magnetic field strength, one can

determine the spatial variation and time dependence of

concentration in a ferrofluid subjected to a magnetic

field gradient. Other SANS experiments have shown

that it is possible to use the anisotropy as a measure

for local variations of flow velocity in a ferrofluid

(Odenbach et al. 1999). The shear in the fluid changes

the mean alignment of the particles with the magnetic

field direction and thus reduces the apparent magnet-

ization in a certain sample volume leading to a change

of anisotropy.

In the characterization of a temperature-sensitive

magnetic fluid the disappearance of magnetic scat-

tering for temperatures above the Curie point has

been used to distinguish between magnetic and nu-

clear scattering, avoiding the loss of intensity con-

nected with the spin flip method discussed above

(Upadhyay et al. 1997).

Finally, powder diffraction with polarized neu-

trons was used as an alternative method to determine

the size distribution of the particles and to get in-

formation about magnetically-disordered layers

(Lin et al. 1995).

7. Outlook

It has been discussed that neutron scattering can be a

helpful tool to investigate the microstructure of mag-

netic fluids, the structure of particles and surfactants

and the formation of clusters, aggregates, and chains.

From this it is astonishing that the amount of work

done in this field is not as high as one would expect

considering the potential of the method. A possible

reason for this could be based on the fact that shortly

after the first efforts in this field the two major neu-

tron sources in Europe, providing sufficient intensity

for ferrofluid experiments—the high flux research re-

actors at ILL in Grenoble and at KFA in Ju

¨

lich, were

out of order for approximately five years for main-

tenance reasons. Now, after restart of both sources,

the activities on neutron scattering experiments with

ferrofluids have been reactivated and new results are

expected in the future. In particular the investigation

of structure formation in the presence of magnetic

field and shear flow—which is the microscopic reason

for the appearance of non-Newtonian effects in ferro-

fluids—is expected to become a vivid field of interest.

See also: Ferrofluids: Introduction; Ferrofluids: Pre-

paration and Physical Properties; Ferrofluids: Mag-

netic Properties; Ferrohydrodynamics

Bibliography

Cebula D J, Charles S W, Popplewell J 1983a Aggregation in

ferrofluids studied by neutron small angle scattering. J. Phys.

44, 207–13

Cebula D J, Charles S W, Popplewell J 1983b Neutron scat-

tering studies of ferrofluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 39, 67–70

Egelstaff P A 1965 Thermal Neutron Scattering. Academic

Press, London

Guinier A 1963 X-ray Diffraction in Crystals. Freeman, San

Francisco, pp. 319–50

Hayter J B, Pynn R, Charles S W, Skjeltorp A T, Trewhella J,

Stubbs G, Timmins P 1989 Ordered macromolecular struc-

tures in ferrofluid mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 1667–70

Lin D, Nunes A C, Majkrzak C F, Berkowitz A E 1995

Polarized neutron study of the magnetization density distri-

bution within a CoFe

2

O

4

colloidal particle. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 145, 343–8

Nunes A C 1988 Effect of magnetic polydispersion in super-

paramagnetic colloids on neutron scattering line shapes. J.

Appl. Cryst. 21, 129–35

Odenbach S, Gilly H, Lindner P 1999 The use of magnetic small

angle neutron scattering for the detection of flow profiles in

magnetic fluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 201, 353–6

Odenbach S, Schwahn D, Stierstadt K 1995 Evidence for dif-

fusion-induced convection in ferrofluids from small angle

neutron scattering. Z. Phys. B 96, 567–9

Potton J A, Daniell G J, Eastop A D, Kitching M, Melville D,

Poslad S, Rainford B D, Stanley H 1983 Ferrofluid particle

size distributions from magnetization and small angle neu-

tron scattering data. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 39, 95–8

Pynn R, Hayter J B, Charles S W 1983 Determination of

ferrofluid structure by neutron polarization analysis. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 51, 710–3

Rosman R, Janssen J J M, Rekveldt M Th 1990 Interparticle

correlations in Fe

3

O

4

ferrofluids, studied by the small angle

neutron scattering technique. J. Appl. Phys. 67, 3072–80

So

¨

ffge F, Schmidbauer E 1981 AC susceptibility and static

magnetic properties of an Fe

3

O

4

ferofluid. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 24, 54–8

Upadhyay R V, Sutariya G M, Mehta R V 1993 Particle size

distribution of a laboratory synthesized magnetic fluid. J.

Magn. Magn. Mater. 123, 262–6

Upadhyay T, Upadhyay R V, Mehta R V, Aswal V K, Goyal P

S 1997 Characterization of a temperature-sensitive magnetic

fluid. Phys. Rev. B 55, 5585–8

S. Odenbach

Universita

¨

t Bremen, Germany

Ferrofluids: Preparation and Physical

Properties

A ferrofluid, or magnetic fluid as it is also commonly

referred to, consists of a stable colloidal suspension of

single-domain nano-sized particles of ferri- or ferro-

magnetic materials in a carrier liquid. A wide range of

carrier liquids have been employed, and many ferro-

fluids are commercially available to satisfy particular

207

Ferrofluids: Preparation and Physical Properties

applications, e.g., in rotary vacuum lead-throughs, it

is essential that the carrier liquid has a very low vapor

pressure. In other applications, temperature—either

high, low, or both—may be a critical consideration.

Theoretically it should be possible to produce dis-

persions in any liquid thereby being able to tailor the

requirements of viscosity, surface tension, tempera-

ture and oxidative stability, vapor pressure, stability

in hostile environments, etc., to the particular appli-

cation in mind, whether it be technological or bio-

medical (see Ferrofluids: Applications).

In order to achieve a stable colloidal suspension,

and in this context stability refers to situations where

the ferrofluid is subjected to a magnetic field, mag-

netic field gradient, and/or gravitational field, the

magnetic particles generally have to be of approxi-

mately 10 nm in diameter. Particles of this size,

whether they are ferrite or metal, possess a single

magnetic domain only, i.e., the individual particles

are in a permanent state of saturation magnetization.

As a result, a strong long-range magnetostatic at-

traction exists between individual particles which

would inevitably lead to agglomeration of the parti-

cles and subsequent sedimentation unless a means of

achieving a repulsive interaction can be incorporated.

A repulsive mechanism (see Ferrofluids: Introduction)

can be achieved by coating the particles with a sur-

face-active material (surfactant) to produce an en-

tropic repulsion or by incorporating a charge on the

surface of the particles thereby producing an electro-

static repulsion. In the case of liquid–metal carriers,

no such interaction has yet been achieved to produce

a stable suspension.

The various methods by which small magnetic

particles can be prepared and subsequently colloidal-

ly dispersed is described in this article. The prepara-

tion of particles and ferrofluids has been the subject

of numerous patents and research publications. A

comprehensive bibliography of this information can

be found updated in each of Proceedings of the In-

ternational Conference on Magnetic Fluids (ICMF),

under the following authors Zahn and Shenton

(1980), Charles and Rosensweig (1983), Kamiyama

and Rosensweig (1987), Blums et al. (1990), Cabuil

et al. (1993), Bhatnagar and Rosensweig (1995). Re-

views of the subject have been given by Rosensweig

(1979, 1985, 1988), Charles and Popplewell (1980),

Martinet (1983) and Scholten (1978).

1. Preparation of Nano-sized Magnetic Particles

The preparation of nano-sized magnetic particles can

be conveniently considered under two headings; one

dealing with metal particles and the other with ferrites.

1.1 Metal Particles

There are a number of methods of producing small

magnetic metallic particles, the commonest of which

for ferrofluid preparation being the decomposition of

organometallic compounds. In addition, reduction of

solutions of metal salts and other miscellaneous

methods are available. The decomposition of organo-

metallic compounds will be discussed in most detail

as it is the easiest and most versatile method of pro-

ducing metal particles suitable for ferrofluids. In most

of these methods, the presence of a surfactant is cru-

cial. By selecting an appropriate surfactant, it has

been shown (Charles and Wells 1990) to be an effec-

tive method of controlling particle size.

There are two major advantages of using ferroflu-

ids based on metallic particles, such as cobalt and

iron particles. First, these metals have high saturation

magnetizations compared with ferrites and second,

they can be produced easily with very narrow size

distributions. However, there is also a major draw-

back which has restricted their use in most commer-

cial applications and that is their poor resistance to

oxidation and subsequent loss of magnetic properties.

Only by maintaining these fluids in an inert atmos-

phere can these fluids possess an extended lifetime.

(a) Decomposition of organometallic compounds

In the 1960s, several groups of workers (Thomas

1966, Hess and Parker 1966) reported the production

of colloidal-sized cobalt particles by the thermolysis

of dicobalt octa-carbonyl in hydrocarbon solutions

containing polymeric materials. The process is very

simple in that it only involves refluxing a solution of

the carbonyl, usually in toluene, until the reaction is

complete, with the formation of cobalt metal parti-

cles. Thomas (1966) showed that the particles possess

a very narrow size distribution ideal for the produc-

tion of stable colloids. The particles also possess an

f.c.c. structure instead of the b.c.c. structure of bulk

cobalt. The absence of a polymer in the thermolysis

leads to the formation of large particles (4100 nm).

A detailed investigation by Hess and Parker (1966) of

the presence of different copolymers of acrylonitrile-

styrene in the reaction solution showed that the

greater the concentration of polar groups along the

polymer chain, the smaller the size of the particles

formed.

It was Smith (1981) who proposed that the reaction

is polymer-catalyzed, which results in the formation

of a polymer–carbonyl complex which then decom-

poses to form elemental cobalt. Papirer et al. (1983)

showed that the decomposition could also be cataly-

zed by the presence of surfactants. They investigated

the evolution of carbon monoxide during the decom-

position in the presence of diethyl-2-hexyl sodium

sulphosuccinate (Manoxol-OT) and in its absence,

both experiments carried out as a function of tem-

perature. The results were consistent with the pres-

ence of ‘‘micro-reactors’’ and a diffusion mechanism

to control the growth. The higher the temperature

used, the smaller the particles produced. During the

208

Ferrofluids: Preparation and Physical Properties

process of thermolysis in toluene, the presence of

Co

4

(CO)

12

was identified as an intermediate.

However, the overall reaction mechanism is com-

plex but it seems likely that a carbonyl complex and/

or microreactors are formed which subsequently de-

compose to produce cobalt particles. Charles and

Wells (1990) investigated methods to control the size

of the cobalt particles formed by the use of a variety

of surfactants and combinations of surfactants. By

taking aliquots of the reaction mixture as the reaction

proceeded and making observations using electron

microscopy, they observed the presence of clusters or

microreactors for the first half hour of a four-hour

reaction but no particles. Subsequently, observations

showed the presence of particles only. They were

able to consistently produce particles with median

diameters in the range 5 to 15 nm. The median di-

ameter refers to a lognormal volume distribution (see

Sect. 1.3).

In many of the papers quoted so far, little infor-

mation has been presented concerning the saturation

magnetization of the particles compared to that of

the bulk. Charles and Wells (1990) found the satu-

ration magnetization of the particles to be consist-

ently lower (75%) than that of the bulk value of

17900 Gauss (1.79 T). This result is in agreement with

the work of Hess and Parker (1966). There are several

possible reasons for this, namely oxidation, spin-pin-

ning/canting, or poor crystallization. Experiments

where care had been taken to avoid oxidation still

showed the reduced saturation magnetization. How-

ever, evidence from x-ray diffraction indicated that

the particles were poorly crystallized or amorphous

with similar results being obtained for iron particles

produced by a similar process (Wonterghem et al.

1986). X-ray diffraction and Mo

¨

ssbauer studies indi-

cated the presence of carbon in the particles which is

thought responsible for the poorly crystallized state.

The particles, when annealed, showed an x-ray

pattern consistent with a-Fe and w-Fe

5

C

2

. Some re-

searchers, using transmission electron diffraction,

have reported that the particles produced by therm-

olysis have a crystalline structure. Whether this is a

true indication of the structure of the particles or that

annealing has taken place in the electron beam is not

known. Measurements of the magnetic anisotropy of

cobalt particles have been undertaken by several

groups of workers (Chantrell et al. 1980, Charles and

Wells 1990).

Iron particles of colloidal dimensions can also be

produced by thermolysis (Wonterghem et al. 1986); in

this case of iron pentacarbonyl in decahydronaph-

thalene. Particle size is again controlled by the pres-

ence of surfactants. The actual structure of the

particles is open to question. Some groups have re-

ported a crystalline structure (Kilner et al. 1984),

whilst others (Wonterghem et al. 1986) reported an

amorphous structure which undergoes crystallization

on annealing.

(Hoon et al. 1983) have reported the preparation of

colloidal nickel particles by the irradiation of nickel

carbonyl with ultraviolet light and by the reduction

of nickelocene. The particles were reported to have an

f.c.c. structure from transmission electron diffraction.

Nakatani and Furubayashi (1990) and Nakatani

et al. (1993) have prepared iron nitride particles by

two methods. First, by a plasma CVD reaction of

iron pentacarbonyl and nitrogen gas and second, by

heating a solution of iron pentacarbonyl in kerosene

containing a surfactant through which a constant

stream of ammonia is passed. The crystal structure

observed is e-Fe

3

N.

It is also possible to prepare alloy particles of the

transition metals by the thermolysis of mixed-metal

organometallic compounds in the presence of surfact-

ants. Lambrick et al. (1985, 1987) prepared organo-

metallic compounds from which particles of Fe–Co

and Ni–Fe alloys with median diameters B8 nm were

obtained. The saturation magnetizations of the par-

ticles are 84% of that of the bulk values.

(b) Reduction of metal salts in aqueous solution

Much of the work on the formation of particles by

the reduction of metal salts in aqueous solution using

reducing agents such as sodium hypophosphite or

sodium borohydride stemmed from an interest in

producing particles suitable for magnetic recording

media. The particles produced were typically of

micron size, which precluded their use in ferrofluids

because of their large magnetic moments and conse-

quent strong magnetostatic interactions.

However, there have been a few reports of the for-

mation of particles of nanometer size which could be

used in ferrofluids. The solutions used in the prepa-

ration contain the salts of ferromagnetic elements, a

reducing agent, complexing agents, and buffers to

control the pH during reaction. The formation of

particles is induced by the addition of PdCl

2

to

the solution. By the introduction of water-soluble

viscosity-increasing materials, it has been shown

(Akashi and Fujyama 1969) that particle size can

be reduced so that the particle can remain in stable

suspension. There have been a few other reports of

the formation of such particles. Harada et al. (1972)

have reported the formation of Co-P particles, using

sodium hypophosphite as reducing agent, in aqueous

solutions containing protein or synthetic polypep-

tides. Similar studies on Fe-P particles have also been

undertaken.

The at.% of phosphorus or boron in the particles is

very dependent on the conditions used. Above a crit-

ical concentration of boron, phosphorus, and indeed

carbon, the particles possess an amorphous structure

very similar to structures produced by rapid-quench

techniques. The incorporation of phosphorus, boron,

and carbon is a disadvantage in one respect, in that

the saturation magnetization of the particles may be

209

Ferrofluids: Preparation and Physical Properties