Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

product liquid. After a prolonged period of grinding

in a ball mill (500–1000 h) near-quantitative conver-

sion of the feed solids to colloidal particles of the

order of 9–10 nm results. A representative composi-

tion consists of magnetite particles, oleic acid disper-

sant, and an aliphatic hydrocarbon carrier such as

hexadecane. Oversize material can be removed by

centrifuging or with magnets and the concentration

of particles adjusted by the evaporation or addition

of the carrier solvent.

The domain magnetization of elemental iron or

cobalt exceeds that of magnetite at normal temper-

atures by three- to four-fold giving incentive to the

preparation of more highly magnetizable ferrofluids

containing these metals. A problem that arises is the

reactivity of the elemental particles with atmospheric

oxygen. Nakatani et al. (1993) prepared dispersions

of iron-nitride particles, e.g., Fe

3

N, in oils. Gaseous

ammonia is bubbled through a solution of liquid iron

carbonyl, Fe(CO)

5

, dissolved in kerosene containing

a polyamine surfactant and produces a well dispersed

colloid with particles of highly uniform size. The iron

nitrides possess a domain magnetization approaching

that of iron and are resistant to oxidation. Ferrofluids

having saturation magnetization up to m

0

M ¼0.233 T

are reported.

3. Colloidal Stability of the Particles

3.1 Stability Against Sedimentation

Ferrofluids employ the same principle that keeps the

atmosphere suspended above the earth, preventing it

from collapsing under gravitational pull, to keep the

tiny magnetic particles suspended. In addition, the

finite size of the particles plays an important role.

Consider a container of ferrofluid exposed to a

nonuniform magnetic field of sufficient intensity to

magnetically saturate the sample at all points. At an

arbitrary point P the magnetic force acting on a unit

volume of the fluid in a given direction s is given from

the Kelvin force expression for dipolar matter as

m

0

mndH/ds where m

0

is the permeability of free space

(4p 10

7

kgms

2

A

2

), m ¼M

d

V

d

is the magnetic

moment of a particle, M

d

is domain magnetization

(4.46 10

5

Am

1

for magnetite), V

d

particle volume

(m

3

), n the number concentration of particles (m

3

),

and H magnetic field magnitude (Am

1

) where

B ¼m

0

(H þM). Balance of the forces acting at equi-

librium on a differential slice of the medium centered

about P and oriented perpendicular to s yields the

relationship:

dp ¼ m

0

mndH ¼ m

0

M

d

efdH ð2Þ

where p is osmotic pressure of the particles (regarding

the particles as a gas occupying the volume of the

fluid space), M

d

is domain magnetization (4.46 10

5

for magnetite) e the volume fraction within a coated

particle that is magnetic, and f the local volume

fraction of coated particles in the ferrofluid. An

equation of state relates p to the concentration of the

particles.

A semi-van der Waals relationship that accounts

for the volume occupied by the particles is given by:

p

1

f

1

f

m

¼

kT

V

d

ð3Þ

where f

m

is the maximum value of f to which the

colloid can be concentrated as limited by the size

of the coated particles, k the Boltzmann constant

(1.38 10

23

NmK

1

), and T absolute temperature

(K). A representative value of f

m

is 0.74 correspond-

ing to hexagonal close packed spheres, and a typical

value of e is 0.36 corresponding to 10 nm core par-

ticles coated with a surfactant of 2 nm thickness.

Combining Eqns. (2) and (3) to eliminate p yields a

differential equation governing the distribution of the

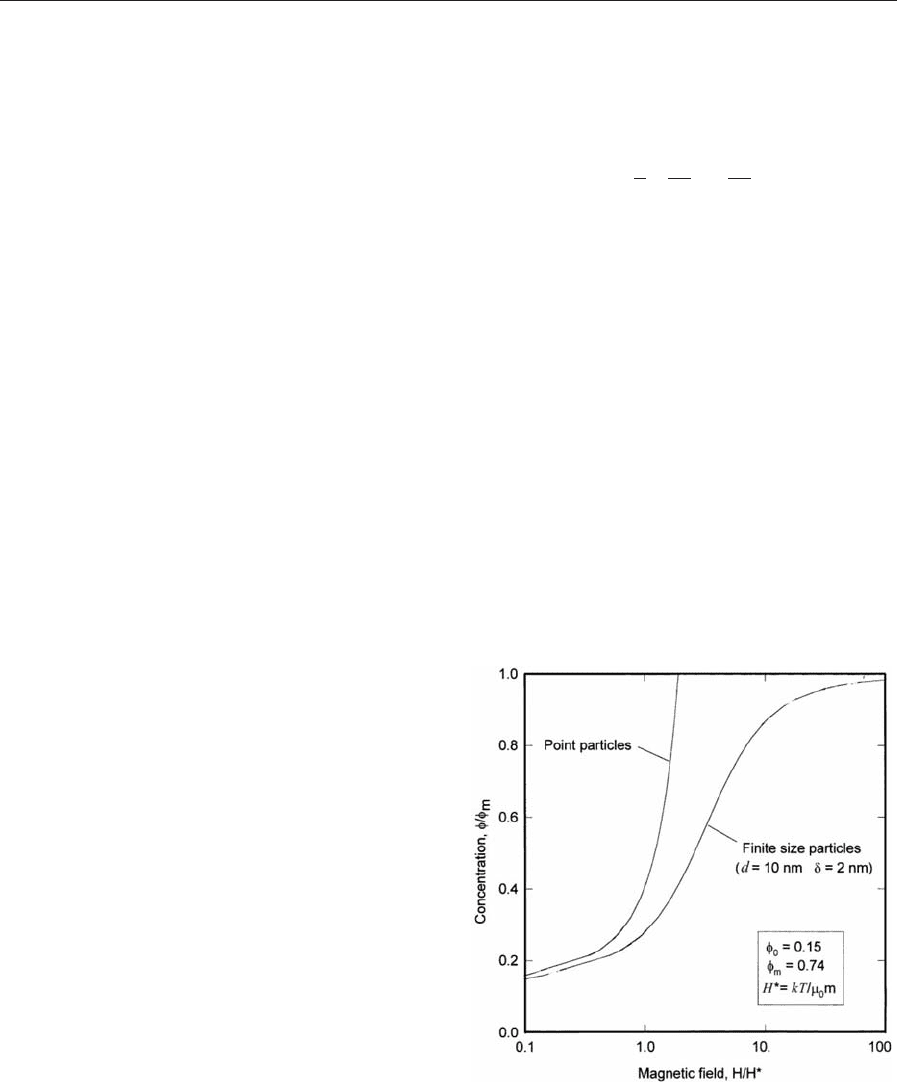

particles. Integration yields the plot of Fig. 2 showing

the distribution of the finite size particles as a func-

tion of the local field; concentration never exceeds the

maximum value which is less than one. A curve

showing the distribution for point particles is shown

for comparison. In the application of ferrofluids to

zero leakage rotary shaft seals and related devices, a

concentrated ferrofluid is generally employed. The

steric hindrance due to the finite particle size is re-

sponsible for the high retention of fluid homogeneity

required for the successful operation of these devices.

Figure 2

Sedimentation equilibrium of ferrofluid particle

concentration in nonuniform magnetic field. The steric

hindrance of finite-size particles limits their maximum

concentration to a physically realistic value.

190

Ferrofluids: Introduction

3.2 Stability Against Agglomeration

A typical ferrofluid contains on the order of 10

17

particles per cubic centimeter, and collisions between

particles are frequent. Hence, if the particles adhere

together, agglomeration will be rapid. The particles

are permanently magnetized, so the maximum energy

to overcome the magnetic attraction between a pair

of particles each of radius, R, occurs when the par-

ticles are aligned. The corresponding dipole–dipole

magnetic interaction is given by:

E

M

¼

8pm

0

M

2

d

R

3

9ðx þ 2Þ

3

ð4Þ

where x ¼s/R with s the surface to surface separation

distance.

In addition, van der Waals forces of attraction

arise between neutral particles due to the fluctuating

electric dipole-induced dipole forces that are always

present. It is also necessary to guard against these

forces. London’s model predicts an inverse sixth

power law between point particles which Hamaker

extended to apply to equal spheres with the following

result.

E

V

¼

A

6

2

x

2

þ 4x

þ

2

ðx þ 2Þ

2

þ ln

x

2

þ 4x

ðx þ 2Þ

2

"#

ð5Þ

A is the Hamaker constant, roughly calculable

from the optical dielectric properties of particles and

the medium. For Fe, Fe

2

O

3

,orFe

3

O

4

in hydrocarbon

carrier, A ¼10

19

Nm is representative within a fac-

tor of three.

A technique to prevent particles from approaching

too close to one another is the steric repulsion arising

from the presence of long chain molecules adsorbed

onto the particle surface. A lattice model for the steric

repulsion based on the theory of polymer configura-

tions in a good solvent (deGennes 1975) yields an

expression for steric repulsion E

S

.

E

S

¼kT

d

3

a

3

ln

1

1 f

s

f

s

p

12

2 x

R

d

2

6

R

d

þ 5

"#

ð6Þ

In Eqn. (6) d is coating thickness, a is the length

associated with the lattice spacing, i.e., the correla-

tion length along a chain, and f

s

is mean volume

fraction of surfactant in the space between the sur-

faces.

The net sum, E

N

, of the magnetic, van der Waals,

and steric energy terms is decisive for determining

monodispersity of the colloidal ferrofluid.

E

N

¼ E

M

þ E

V

þ E

S

ð7Þ

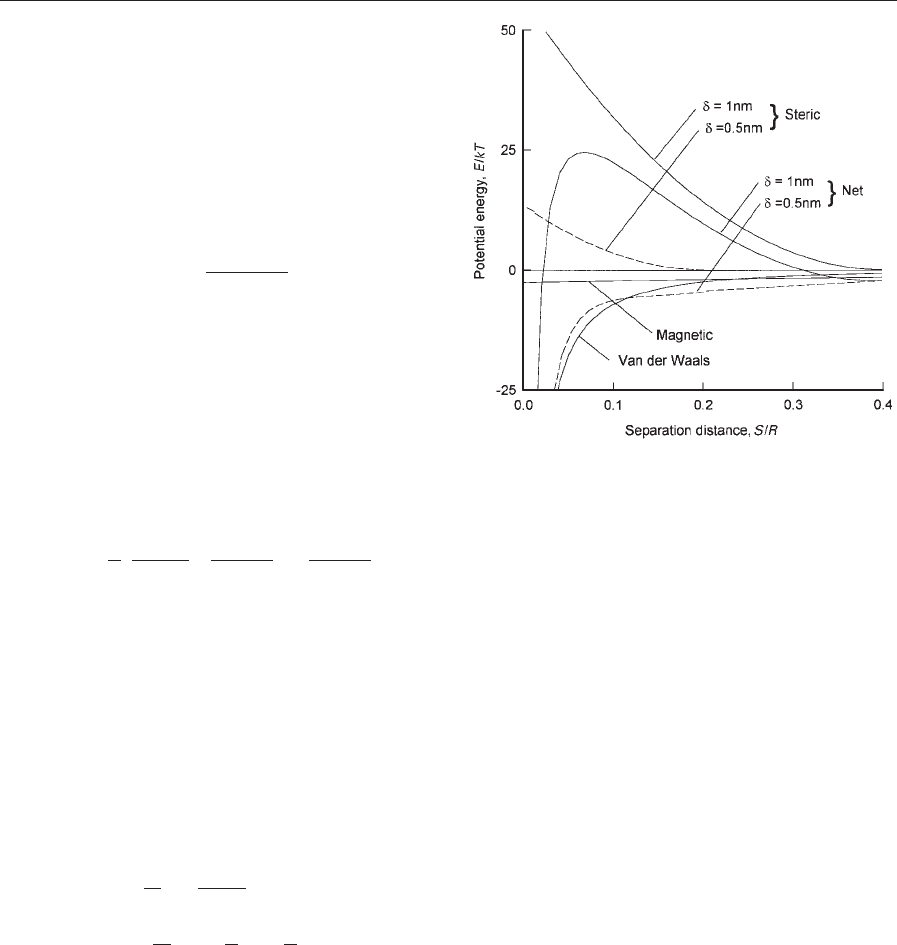

Figure 3 illustrates calculated behavior for given

size particles with two different thicknesses of coat-

ings. The curve of magnetic energy is the same in

both cases as is the distribution of van der Waals

energy. Magnetic interaction can nearly be neglected

in comparison. Steric repulsion with the thicker coat-

ing (1 nm) yields a net energy curve presenting a bar-

rier energy of nearly 25 kT. Statistically, few particles

cross the barrier and the colloid is stable against ag-

glomeration. The thin coating (0.5 nm) yields a net

energy curve that is attractive at all distances thus

yielding an unstable preparation.

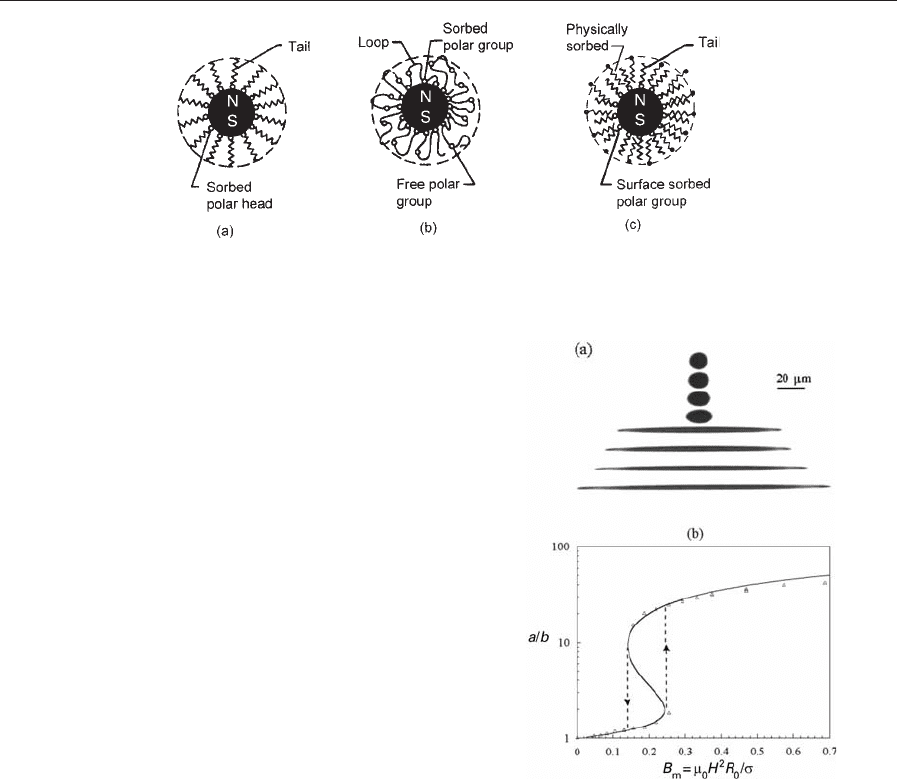

Various sorbent configurations that confer steric

stability to ferrofluids are illustrated schematically in

Fig. 4. A particle coated with a sorbed monolayer of

a long tail molecule having a polar head group, e.g.,

oleic acid, is shown in Fig. 4(a). Figure 4(b) illustrates

a polymeric species having multiple polar groups dis-

tributed along its length. Loops of polymer rather

than tails serve as the protective layer. Because more

than one polar group attaches to the particle surface,

the colloidal stability at elevated temperatures is

enhanced; polybutenylsuccinpolyamines are an ex-

ample. Figure 4(c) illustrates a double layer config-

uration with inwardly oriented tails of polar

molecules in an outer layer associated with the tails

of the surface-sorbed layer. This configuration serves

to disperse particles in aqueous media. Example

combinations are: sodium oleate/sodium oleate and

sodium oleate/sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate.

Figure 3

Potential energy versus surface separation distance of

sterically protected 10 nm magnetite particles of a

ferrofluid. A net energy barrier greater than about 10 kT

prevents agglomeration of particles.

191

Ferrofluids: Introduction

Charge stabilized colloids prepared with the Mass-

art technique use the sorption of small moities to

adjust electrical charge on the particle. Sorption of

tetramethylammonium ion ðNðCH

3

Þ

þ

4

Þ yields stable

dispersions in alkaline solution (pH49) where hy-

droxyl ion (OH

) furnishes the counterion, whereas

perchlorate ion ðClO

4

Þ and nitrate ðNO

3

Þ peptize

particles in acidic media (pHo5) where hydrogen

ions (H

þ

) are the counterions. Magnetic particles

coated with citrate ligands are peptizable at interme-

diate levels of pH and are candidates for medical

application at neutral pH.

4. Phase Transition

Under certain conditions, ferrofluids undergo phase

separation in which micronic droplets of a concen-

trated phase exist in equilibrium with a continuous

dilute phase. The appearance of a drop is shown in

Fig. 5(a). The phenomenon can be brought on in

various ways—by application of magnetic field in-

tensity in excess of a critical value, addition of a

foreign solvent, change of pH or counter ion con-

centration of an electrically stabilized preparation,

and by reduction of temperature. It is sometimes

possible to take advantage of such a phase separa-

tion, e.g., to sort particles by size, or to induce colors

in thin layers by diffraction of light. In other cases,

where a dilute magnetic fluid is retained by applica-

tion of a field gradient, the separation can lead to

undesired weeping of the dilute phase.

Optical methods are useful for detecting the drop-

lets. Direct microscopic observation via light trans-

mitted through a thin layer is possible for droplets

having size of a few micrometers; the layer is trans-

parent red-orange in the homogeneous region. Laser

light scattering being very sensitive to the presence of

small clusters may be more suitable for direct detec-

tion of the very onset of the transition.

Figure 6 shows coexistence curves for a hydro-

carbon-based ferrofluid that has particle size d

mp

¼

7.4 nm as determined by electron microscopy. Field

intensity producing transition can be increased using

a sample containing smaller size particles. A sample

with particle sizes d ¼5.0 nm tested homogeneous

at all concentrations in the highest field applied

(12.7 Am

1

).

5. Ferrofluid Modification

If an excess of a polar solvent such as acetone or

a lower molecular weight alcohol is added to an

Figure 4

Sorbed protective layers of various types yield stably dispersed particles in a ferrofluid.

Figure 5

As shown in (a) a stretched droplet of phase-separated

ionic ferrofluid exhibits a jump in length as applied field

exceeds a critical value; (b): hysteresis results when field

is decreased. Viscosity of the drop phase exceeds that of

the dilute phase by a factor of more than 300 as

determined from birefringence (after Bacri and Salin

1983).

192

Ferrofluids: Introduction

oleic-acid-stabilized ferrofluid in hydrocarbon carrier

the magnetite particles flocculate and settle out in an

external force field. Evidently, the surface layer re-

tracts and becomes ineffective in providing steric re-

pulsion. The particles redisperse spontaneously when

fresh solvent is added, showing that the surfactant

remains bound onto the particle surface. The tech-

nique permits the concentration of the colloid to be

adjusted and excess surfactant removed. Removing

the excess generally reduces the viscosity, especially

of high concentration, more magnetic preparations.

Also, the initial solvent, e.g., high volatility heptane,

can be exchanged for one of low volatility, useful in

applications where the ferrofluid is exposed to the

atmosphere as in magnetic fluid rotary shaft seals and

acoustic drivers.

Certain surfactants are only weakly adsorbed and

dissolve off into the polar liquid mixture. Contacting

the settled out particles with fresh solvent fails to

produce a stable dispersion. An example is aqueous

ferrofluid having particles coated with Aerosol C61,

an amine complex. After washing the precipitated

particles with solvent, a different surfactant may be

added which is capable of strongly adsorbing onto

the particle surface. The new surfactant can be cho-

sen to confer dispersibility of the particles in a totally

different solvent. The technique confers great flexi-

bility in the production of ferrofluids in diverse car-

riers such as mineral oils, esters, silicones, etc.

6. Magnetic Properties

6.1 Equilibrium Magnetization

The magnetic torque, t, experienced by a single par-

ticle of volume V and domain magnetization M

d

whose moment is oriented at angle y to applied in-

duction B is given by t ¼mHsiny where m ¼M

d

V is

the magnetic moment of the particle. The associated

energy to rotate the particle away from alignment

with the field is W ¼mB(1cosy) with the probability

p(y) of finding a particle oriented between angle y

and y þdy proportional to the Boltzmann factor

exp(W/kT) times the steradians in orientational

space, sinydy, with the component of the moment

along the field direction given by mcosy. The mean

value of magnetization for monodisperse particles is

given by the integration:

%

m

m

¼

R

p

0

cosðyÞpðyÞdy

R

p

0

pðyÞdy

¼ cothg

1

g

RLðgÞð8Þ

where L(g) is the Langevin function and g ¼mB/kT.

L(g) ¼g/3 for g51 and L(g) ¼11/g for gb1. Noting

that

%

m=m ¼ M=M

s

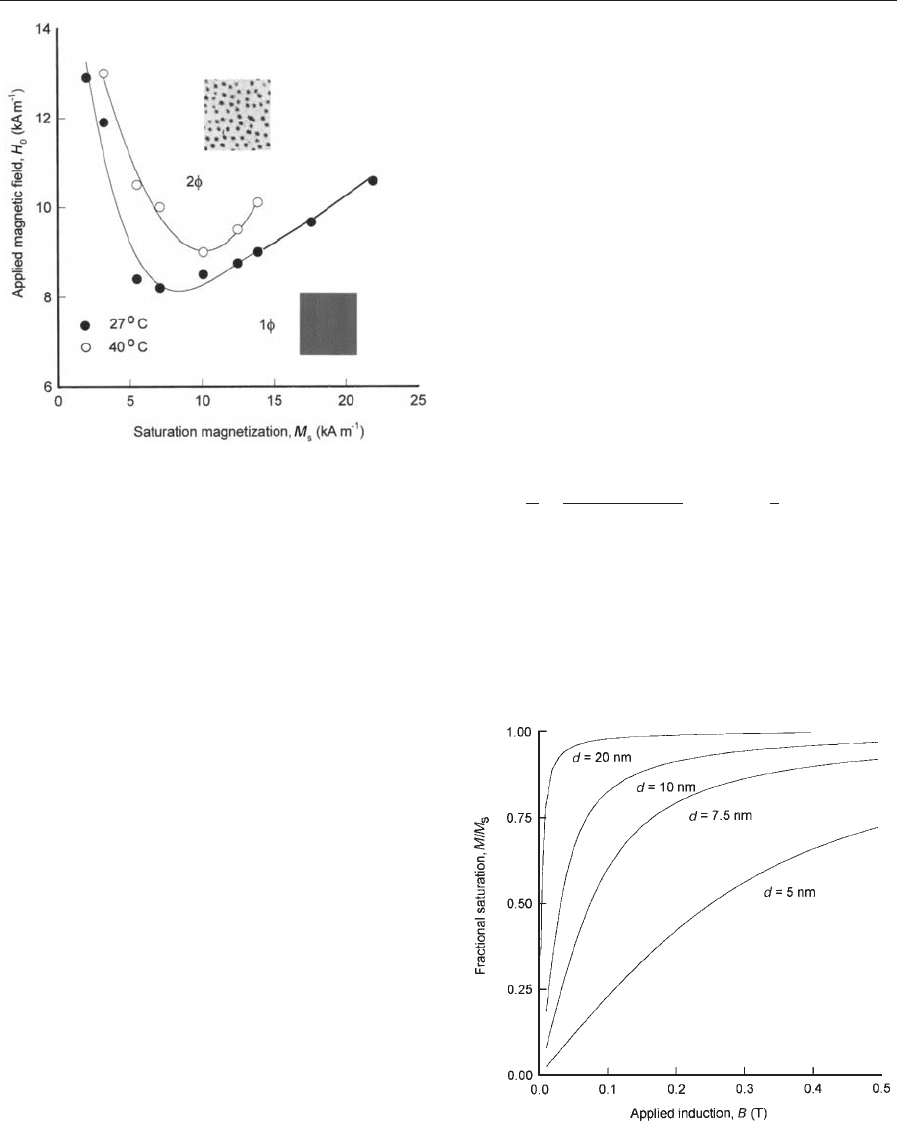

where M is magnetization of the

ferrofluid and M

s

is the saturation value of M, mag-

netization curves for monodisperse spherical particles

calculated with the domain magnetization of mag-

netite are shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 6

Coexistence curves for a hydrocarbon-based ferrofluid

of magnetite particles. Insets show appearance of a thin

layer seen through a microscope: one-phase region

shows homogeneous coloring; cross-sections of

stretched droplets in the two-phase region form a

patterned array due to mutual repulsion; applied field is

normal to the layer (after Popplewell and Rosensweig

1992).

Figure 7

Magnetization curves computed from the Langevin

relationship (magnetite, M

d

¼4.46 10

5

Am

1

).

193

Ferrofluids: Introduction

For a polydisperse system the shape of the mag-

netization curve depends on the distribution of par-

ticle sizes. Commonly a good fit to the distribution is

given by the log normal distribution function P(d)

where P(d)d(d) is the fraction of total magnetic vol-

ume having diameter between d and d þd(d).

PðdÞ¼

1

sd

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

2p

p

exp

ln

2

ðd=d

0

Þ

2s

2

ð9aÞ

and

Z

N

0

PðdÞdðdÞ¼1 ð9bÞ

where ln(d

0

) is the mean of ln(d), d

0

is the median

diameter, and s is its standard deviation The most

probable diameter is given by d

mp

¼d

0

exp(s

2

), the

mean diameter /dS ¼d

0

exp(s

2

/2), and higher mo-

ments /d

n

S ¼d

0

n

exp(n

2

s

2

/2). Taking size distribution

into account the magnetization curve is given by:

MðHÞ¼

Z

N

0

Mðd; HÞPðdÞdd ð10Þ

Chantrell et al. (1978) used expansions of the La-

ngevin function together with the log normal distri-

bution to obtain the following expressions for median

diameter, d

0

, and standard deviation, s, from a mag-

netization curve of a polydisperse system.

s ¼

1

3

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ln

3w

M

s

=H

0

s

ð11aÞ

d

0

¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

w

3M

s

H

0

r

18kT

pM

d

1

3

ð11bÞ

where w is the initial susceptility of the fluid and 1/H

0

is the extrapolation to M ¼0 of the straight line

obtained for high fields when plotting M ¼f(1/H).

Measured values of magnetization for dilute ferro-

fluids are in good agreement with the superparamag-

netic relationship when the distribution of particle

size is taken into account. Dipole–dipole interaction

between particles elevates the low field portion of the

magnetization curve for ferrofluids having parameter

m

0

M

2

d

V=kTE30 or greater.

Temperature dependence of magnetization is of

interest in problems of thermal convection. The

pyromagnetic coefficient K ¼@M/@T depends on

domain magnetization, fluid expansion coefficient,

particle volume fraction, and thermal disorientation

which can be modeled with the Langevin function.

6.2 Anomalous Susceptibility

The initial susceptibility w ¼M/H of ferrofluid con-

taining noninteracting particles can be computed

from the expansion of Eqn. (8) as L(g) ¼M/M

s

¼g/3

where M

s

is the saturation magnetization of the

ferrofluid and a is the Langevin argument. Thus

w ¼pm

0

d

3

M

d

M

s

/18kT where M

d

is the domain mag-

netization of the magnetic particles. For a concen-

trated phase of 12 nm magnetite particles with

m

0

M

s

¼0.1T the value of w is 3.27. Polydisperse

ferrofluid samples posess susceptibilities that are con-

sistent with this estimate. However, as seen previous-

ly, values of w in the droplets of a phase-separated

sample are more than an order of magnitude larger.

An in situ measurement based on elongation behavior

of a droplet as a function of applied magnetic field

intensity provides an elegant means for measuring the

susceptibility as discussed in the following.

Using ionic ferrofluid the elongated deformation is

obtained in fields of very low intensity, of the order of

120 Am

1

(1.5 Oe). Above a threshold value of the

magnetic Bond number, B

m

¼m

0

H

2

R

0

/s

t

,whereR

0

is

radius of an initially spherical drop and s

t

interfacial

tension, the drop experiences an elongational shape

instability characterized by a steep jump of its aspect

ratio. The S-shape curve, see Fig. 5(b) can be fitted to a

theoretical expression assuming an ellipsoidal prolate

shape allowing susceptibilitiy w and s

t

to be deduced.

The minimum susceptiblity to achieve the hard tran-

sition occurs at about w ¼18. For this data w ¼75710

and s ¼972 10

7

Nm

1

with R

0

¼6.5 mm.

Subjected to a rotating magnetic field, the drops

first elongate and spin, develop arms reminiscent of

starfish, and undergo other transitions depending on

field rotational frequency and intensity.

6.3 Nonequilibrium Magnetization

The vectorial magnetization, M

0

, in equilibrium with

steady magnetic field, H, in motionless fluid is aligned

in the direction of H and possesses magnetization

magnitude M

0

given, for example, by the Langevin

relationship. However, in the presence of time-vary-

ing magnetic field magnitude or orientation the mag-

netization, M, lags behind the field and differs from

M

0

. Models have been developed (Shliomis 1974,

Martsenyuk et al. 1973) to treat this behavior which

has importance to dynamic flows of ferrofluids.

Measurement of the frequency response of mag-

netization of a ferrofluid yields information concern-

ing the relaxation mechanism (Fannin et al. 1990).

7. Viscosity of Ferrofluid

7.1 Viscosity in Absence of Field

In 1906, Einstein derived the earliest theory for non-

interacting spheres suspended in a liquid based on the

flow field of pure rate-of-strain perturbed by the

presence of the sphere. The resulting formula relates

the mixture viscosity, Z, to the carrier fluid viscosity,

194

Ferrofluids: Introduction

Z

0

, and solids fraction, f, in the form Z/Z

0

¼1 þ5f/2.

This relationship has been extended by Batchelor to

second order in concentration. For higher concen-

trations, a parameterized expression may be assumed

of the form Z/Z

0

¼1/(1 þaf þbf

2

) with insistence

that the expression (i) reduce to the Einstein rela-

tionship for small values of f so that a ¼5/2; (ii) the

suspension becomes effectively rigid at a concentra-

tion, f

c

, indicative of close packing (0.74 for close

packed spheres); and (iii) core particles of volume

fraction f coated with dispersing agent of thickness d

occupies volume fraction f(1 þd/r)

3

where r is radius

of the core particle. Combining these relationships

results in the expression:

Z Z

0

fZ

¼

5

2

1 þ

d

r

3

5f

c

=2 1

f

2

c

!

1 þ

d

r

6

f ð 12Þ

If particles have a tendency to cluster and form a

gel network, the value of f

c

is less than 0.74. For f

c

less than 0.4 the coefficient of the last term in Eqn.

(12), and hence the slope of a plot of (Z – Z

c

)/fZ vs. f

changes sign, a phenomenon that has been observed

for certain ferrofluids.

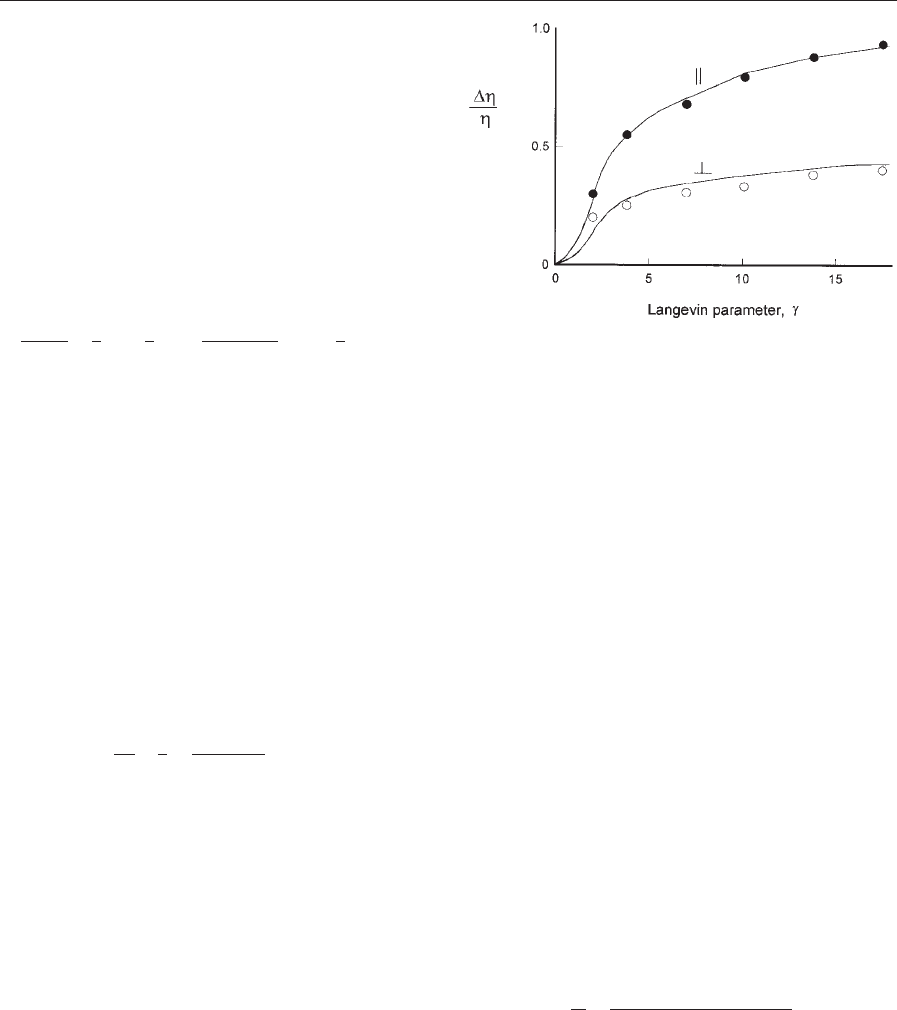

7.2 Viscosity in Magnetic Field

When a magnetic field is applied to a ferrofluid that is

sheared, the magnetic particles in the fluid tend to

remain aligned in the direction of the orienting field

and viscous dissipation in the fluid increases. A the-

oretical treatment (Shliomis 1974) for dilute suspen-

sions of particles with large Ne

´

el time constant and

accounting for the Brownian rotational motion gives

DZ

Z

¼

3

2

f

g tanhg

g þ tanhg

sin

2

b ð13Þ

where g is the Langevin parameter, b the angle be-

tween the magnetic field, H, and the fluid vorticity,

X ¼X v, where v is the fluid velocity vector. The

vorticity is twice the local average spin rate of the

colloid. Magnetic particles rotate freely when the ro-

tational and magnetic axes are aligned with the local

field direction but are hindered otherwise. In laminar

flow through a circular tube (Poiseuille flow) the

vorticity magnitude is constant on concentric circles

in a cross-section normal to the axis of the tube. For

field oriented parallel to the axis, sin

2

b ¼1 while for

perpendicular orientation of the field relative to the

tube axis, averaging over b gives /sin

2

bS ¼1/2.

Hence, for any applied magnetic field intensity,

DZ

77

¼2DZ

>

. As seen in Fig. 8, the theoretical curves

(solid lines) agree well with the experimental data of

McTague (1969) for a dilute suspension of polymer-

stabilized cobalt particles in toluene.

In alternating, linearly polarized magnetic field,

the viscosity of a ferrofluid can exhibit a substantial

reduction, i.e., a negative viscosity component

(Shliomis and Morozov 1994). The particles of the

ferrofluid act as tiny motors rotating faster than the

vorticity spin rate thus helping to propel the fluid.

8. Other Physica l Properties

Mass density and specific heat of ferrofluids is esti-

mated as the volumetric average of particle and

matrix liquid values assuming surfactant to possess

properties of the carrier liquid. Pour point and vapor

pressure can be estimated as that of the carrier liquid.

Surface tension at ambient temperatures of sterically-

stabilized aqueous ferrofluid is reduced from that of

water (72 mNm

1

) to a typical value of 26 mNm

1

,

most likely due to free surfactant concentrated at the

air interface. Interfacial tension for ferrofluids in var-

ious organic alkanes and esters ranges typically from

20 to 32 mNm

1

depending on the carrier.

The thermal conductivity, l, of a composite con-

sisting of particles in a matrix fluid is described by the

Maxwell formula obtained by comparing the thermal

field with the analogous electrical field and it is as-

sumed that ferrofluids can be described in this man-

ner also.

l

l

c

¼

2l

c

þ l

p

þ 2f

p

ðl

p

l

c

Þ

2l

c

þ l

p

f

p

ðl

p

l

c

Þ

ð14Þ

where l

c

is thermal conductivity of the carrier solution,

l

p

the thermal conductivity of the particles, and f

p

the

particle volumetric concentration. Solids conductivity

may differ significantly from that of the carrier, e.g.,

for g-Fe

2

O

3

and perhaps magnetite l

p

E6Wm

1

K

1

while for an oil l

c

E0.13 W m

1

K

1

. Thus, the solids

volumetric concentration must considerably affect the

Figure 8

Magnetoviscosity of a dilute ferrofluid containing

particles of elemental cobalt. Data of McTague (1963)

compared to theory (after Shliomis and Raikher 1980).

195

Ferrofluids: Introduction

thermal conductivity of the ferrofluid. Data of mag-

netite-in-kerosene ferrofluid show a range 1.0ol/

l

c

o2.0 with maximum concentration of f ¼0.2. Mag-

netic field oriented normal to the temperature gradient

does not affect l.

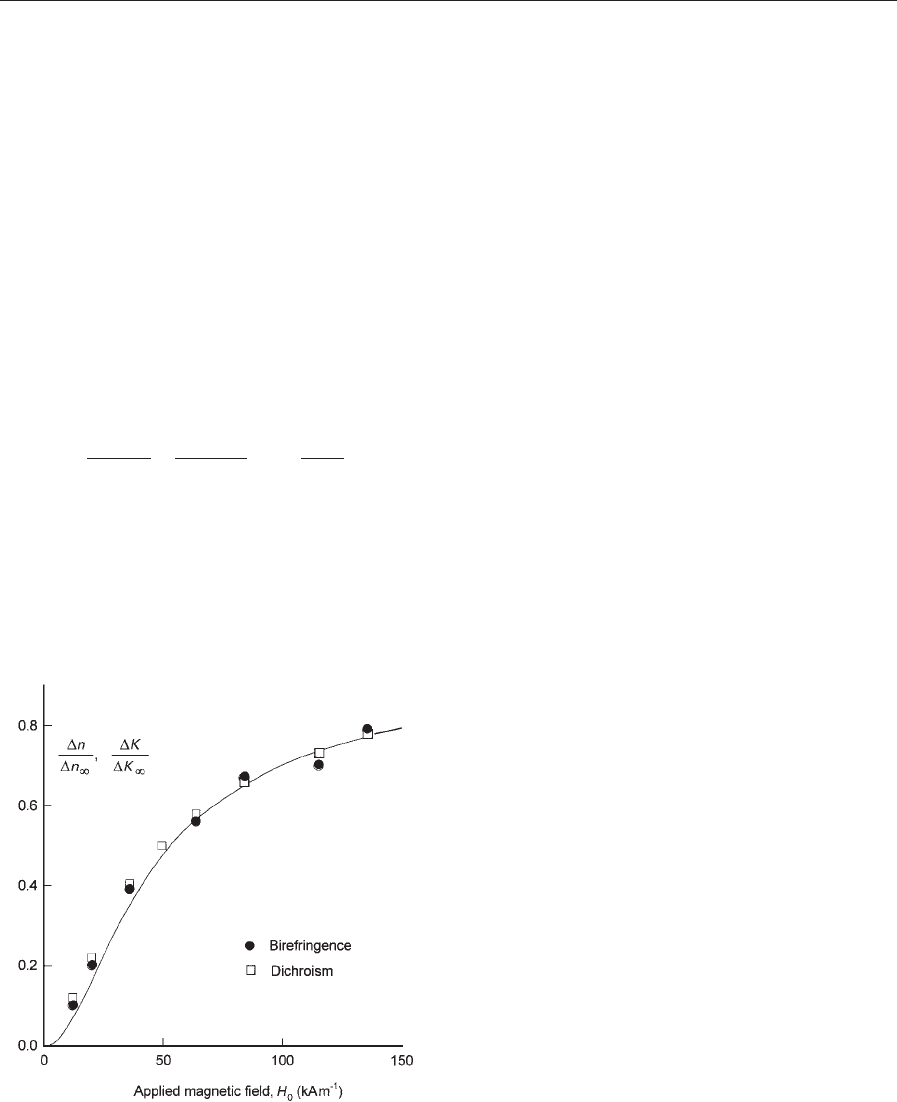

Ferrofluid solutions when sufficiently dilute or in a

thin enough layer transmit a light beam, and the

normally isotropic fluid becomes optically aniso-

tropic in an applied magnetic field, H. Properties

of interest include birefringence, dichroism, and

Faraday rotation.

Birefringence and dichroism in homogeneous sam-

ples is attributed to the shape anisotropy of particles

and possibly correlations between neighbors. The in-

fluence of an individual particle depends on the ori-

entation of its axis relative to the electric field of

the incident light ray. Analysis that averages over

orientations yields a dependence on applied field in-

tensity that is the same for both phenomena

(Shliomis and Raikher 1980).

n

77

n

>

Dn

N

¼

K

77

K

>

DK

N

¼ 1

3LðgÞ

g

ð15Þ

where n

0

i

and K

i

are components of refractive index

and adsorption coefficient, respectively. Figure 9 il-

lustrates the favorable comparison of data and pre-

dictions for a sterically-stabilized ferrofluid. Using

birefringence detection with a sample having volu-

metric particle fraction of less than 10

3

as a sensor,

the viscosity of carrier liquids was measured with an

accuracy of 5% over a viscosity range of seven dec-

ades (Bacri et al. 1985). The viscosity of the solu-

tions was negligibly changed by presence of the

particles, less than 2.5 parts per thousand using the

Einstein relationship. Bibette (1993) produced a

monodisperse emulsion of oil base ferrofluid drop-

lets in an aqueous carrier and optically measured

force vs. distance characterizing the electrostatic

double layer surrounding the droplets. Modulation

of the applied magnetic field was used to control the

attraction between droplets, hence their separation

distance.

9. Status and Future Directions

Scientific understanding of ferrofluids as a material

has progressed greatly. Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Conferences on Magnetic Fluids (Elsevier,

North-Holland, Publishers) are a rich source of in-

formation including bibliographies of patents and the

literature. The influence of magnetic and thermal

fields on the hydrodynamics of ferrofluids, i.e., ferro-

hydrodynamics, is highly developed. Commercial

applications of ferrofluids range from tribology to

instrumentation to densimetric separation of miner-

als, and many other uses are in stages of research.

Materials research challenges for the future include:

development of stable fluids having larger saturation

moments, conjugation of ferrofluid particles with

protein species for drug delivery and medical imag-

ing, development of ferrofluid inks in various colors,

ferrofluids possessing greater monodispersity, stable

ferrofluids in liquid metal carrier, and ferrofluid com-

posites with tailored properties.

See also: Ferrofluids: Applications Ferrofluids: Neu-

tron Scattering Studies; Ferrofluids: Preparation and

Physical Properties; Ferrohydrodynamics

Bibliography

Bacri J-C, Dumas J, Gorse D, Perzynski R, Salin D 1985

Ferrofluid viscometer. J. Phys. Lett. 46, L1199–205

Bacri J-C, Perzynski R, Salin D, Cebers A O 1992 Instabilities

of a ferrofluid droplet in alternating and rotating magnetic

fields. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 248, 241–6

Bacri J-C, Salin D 1983 Dynamics of the shape transition of a

magnetic ferrofluid drop. J. Phys. Lett. 44, 415–20

Bashtovoy V G, Berkovsky B M, Vislovich A N 1988 Intro-

duction to Thermomechanics of Magnetic Fluids. Hemisphere,

Washington, DC

Berkovsky B (ed.) 1996 Magnetic Fluids and Applications Hand-

book. Begell House, New York

Bibette J 1993 Monodisperse ferrofluid emulsions. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater. 122, 37–41

Blums E, Cebers A, Maiorov M M 1997 Magnetic Fluids.

Walter de Gruyter, Berlin

Figure 9

Dependence on magnetic field of birefringence and

dichroism for a hydrocarbon base ferrofluid compared

to theory.

196

Ferrofluids: Introduction

Chantrell R W, Popplewell J, Charles S W 1978 Measurements

of particle size distribution parameters in ferrofluids. IEEE

Trans. Magn. MAG-16, 975–7

de Gennes P G 1975 Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics.

Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, p. 74

Elmore W C 1938a Ferromagnetic colloid for studying mag-

netic structures. Phys. Rev. 54, 309–10

Elmore W C 1938b The magnetization of ferromagnetic col-

loids. Phys. Rev. A24, 1092–5

Fannin P C, Scaife B K P, Charles S W 1990 A study of the

complex ac susceptibility of magnetic fluids subjected to a

constant polarizing magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.

85, 54–6

Gable H S, Kerr G W 1977 Magnetic organo-iron compounds.

US Pat. 4 001 288 (CIP of copending application Ser. No.

487 564 filed Sept. 15, 1965)

Khalafalla S E, Reimers G W 1973 Magnetofluids and their

manufacture. US Pat. 3 764 540

Khalafalla S E, Reimers G W 1974 Production of magnetic

fluids by peptization techniques. US Pat. 3 843 540

Martsenyuk M A, Raikher Yu L, Shliomis M I 1973 On the

kinetics of magnetization of suspensions of single domain

particles. Sov. Phys. JETP 38, 413–6

Massart R 1981 Preparation of aqueous magnetic liquids in

alkaline and acidic media. IEEE Trans. Magn. MAG-17,

1247–8

Massart R 1996 Dispersion of particles in the base liquid. In:

Berkovsky B (ed.) Magnetic Fluids and Applications Hand-

book. Begell House, New York

McTague J P 1969 Magnetoviscosity of magnetic colloids. J.

Chem. Phys. 51, 133–6

Nakatani I, Hijikata M, Ozawa K 1993 Iron-nitride magnetic

fluids prepared by vapor-liquid reaction and their magnetic

properties. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 122, 10–4

O’Connor T L 1962 Preparation of sols of metal oxides. Belg.

Pat. 613 716

Papell S S 1965 Low viscosity magnetic fluid obtained by the

colloidal suspension of magnetic particles. US Pat. 3 215 572

Popplewell J, Rosensweig R E 1992 Influence of concentration

on field-induced phase transition in magnetic fluids. Int. J.

Appl. Electromagn. Mater. 2 (Suppl.), 83–6

Rosensweig R E 1985 Ferrohydrodynamics, Cambridge Mono-

graphs on Mechanics and Applied Mathematics. Cambridge

University Press, New York [Republished 1997. Dover Pub-

lications, Mineola, NY]

Rosensweig R E, Nestor J W, Timmins R S 1965 Ferrohydro-

dynamic fluids for direct conversion of heat energy. Materials

Association Direct Energy Conversion Symposium Proceed-

ings. AIChE—I. Chem. Eng. Ser. 5, 104–18 discussion,

133–7

Sandre O, Browaeys J, Perzynski R, Bacri J -C, Cabuil V,

Rosensweig R E 1999 Assembly of microscopic highly mag-

netic droplets: magnetic alignment versus viscous drag. Phys.

Rev. E 59, 1736–46

Scholten P C 1980 The origin of birefringence and dichroism in

magnetic fluids. IEEE Trans. Magn. MAG-16, 221–5

Shliomis M I 1974 Magnetic fluids. Sov. Phys. Usp. 112, 153–69

Shliomis M I, Raikher Yu L 1980 Experimental investigations

of magnetic fluids. IEEE Trans. Magn. MAG-16, 237–50

Shliomis M I, Morozov K I 1994 Negative viscosity under

alternating magnetic field. Phys. Fluids 6, 2855–61

R. E. Rosensweig

Fondation de l’Ecole Normale Supe

´

rieure

Paris, France

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

The magnetic properties of ferrofluids are dominated

by the intrinsic magnetic properties of the particles

themselves. These are governed by dynamical effects

due to Ne

´

el relaxation in the solid and Brownian

motion in the fluid, and influenced by the interpar-

ticle interaction.

1. Single-domain Particles

The particles have diameters in the range of typically

2–20 nm. The size is generally below the critical limit,

dependent on the specific ferromagnet, where a mag-

netic domain structure can form, and so the particles

can be considered as single domain. Because of the

nanometer-scaled size, finite-size effects are signifi-

cant. Surface effects influence the intrinsic properties

(e.g., magnetization, magnetocrystalline anisotropy).

The breaking of symmetry results in site-specific sur-

face anisotropy; the reduced number of magnetic

neighbors and specific electronic and structural fea-

tures lead to magnetic disorder and weakened ex-

change coupling, with possible effects on atomic

moments. All phenomena depend on the surface

microstructure and can vary with the surroundings.

Volume effects influence the behavior of the ex-

change-coupled spin system against excitation. The

particle volume, V, is small enough for coherent spin

reversal (Stoner–Wohlfarth particle), at least on a

macroscopic viewing scale. Because all the spins ro-

tate in unison, except perhaps near the surface, they

can be dealt with collectively via the particle moment

m. Its magnitude is given by

m ¼ M

s

V ð1Þ

where M

s

is the intrinsic magnetization, which is the

magnetic moment per unit volume. It can often be

considered as constantly neglecting its thermal var-

iation. The orientation of m with respect to the lattice

is determined by the total magnetic anisotropy

energy, which results generally from bulk magneto-

crystalline, magnetostatic (shape), and global macro-

scopic surface anisotropies. It can often be considered

uniaxial and is then given by

E ¼ KVsin

2

y ð2Þ

where K (40) is the effective anisotropy energy den-

sity, generally in the range 10

4

–10

6

Jm

3

, and y is the

angle with respect to the symmetry (easy) axis.

Since the anisotropy energy decreases with volume,

the energy barriers separating the easy directions can

be comparable to the thermal energy, kT, even below

room temperature; here, k is Boltzmann’s constant

and T the temperature. m is then no longer fixed in

the lattice, unlike in large crystals, but fluctuates

197

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

among the easy directions. Ne

´

el performed the first

calculation of the relaxation time and this thermo-

activated phenomenon is called Ne

´

el or superpara-

magnetic relaxation. The corresponding magnetic

behavior is called superparamagnetism.

A particle responding to a magnetic field rotates its

moment. In a solid, the rotation occurs inside the

particle (Ne

´

el relaxation). In a ferrofluid, it can also

occur by bulk rotation (Brownian rotational diffu-

sion). The relaxation rates are generally different and

the two processes can often be treated separately.

2. Ne

´

el Relaxation

In a uniform magnetic field H of strength H, the free

energy of an isolated uniaxial particle with aniso-

tropy barrier E

B

¼ KV, fixed in space, is given by

E ¼ E

B

sin

2

y m

0

mHðcos y cos c þ sin y sin c cos jÞð3Þ

where m

0

is the permeability of free space, c the angle

between the easy axis (unit vector e) and field, and j

the longitude of m relative to the plane (e,H). H

K

¼

2E

B

=m

0

m is the anisotropy field. The energy has a

bistable form if the field is not too large, i.e.,

HoH

c

ðcÞ with 1XH

c

=H

K

X1=2. In Brown’s model,

the equation of motion is given by the Gilbert–Land-

au–Lifshitz equation

2t

N0

dm

dt

¼

m

0

kT

mz

1

m H

e

þ m H

e

ðÞm

t

N0

¼

m

2gkT

ðz

1

þ zÞð4Þ

where g is the gyromagnetic ratio (1.7 10

11

s

1

T

1

),

and z (E10

1

210

2

) the dimensionless damping

factor of the precession of m in the effective field

H

e

¼m

1

0

@E=@m þ hðtÞ, where hðtÞ is a random

white-noise field. The probability density of m ori-

entations obeys a Fokker–Planck equation, as is the

case for Brownian motion.

The effective time to surmount the barrier is given

by t

N

¼ 2t

N0

P

N

n¼1

A

n

=l

n

, where l

n

is the nth eigen-

value, and A

n

its amplitude. The lowest (a0) eigen-

value, l

1

, is associated with the overbarrier mode,

and higher ones with intrawell modes. Only the

former is frequently considered and then t

N

¼

2t

N0

=l

1

. If the field is parallel to the easy axis, the

energy barrier is E

B

ð17hÞ

2

with h ¼ H=H

K

, and t

N

is

given by

a ¼

E

B

kT

{1; t

N

¼ t

N0

1

2

5

a þ

48

875

a

2

þ

2

5

a

2

h

2

1

ac1; t

7

¼ t

N0

p

1=2

a

3=2

ð1 h

2

Þð17hÞ

1

exp½að17hÞ

2

;

t

1

N

¼ t

1

þ

þ t

1

ð5Þ

t

1

þ

and t

1

are the probabilities per unit time of m

reversal from the lower to upper minimum and vice

versa, respectively. For H ¼ 0, t

N

is well approxi-

mated for all barrier heights by

t

N

¼ t

N0

f2a½p

1=2

a

3=2

ða þ 1Þ

1

þ 2

a1

g

1

ðe

a

1Þð6Þ

For ac1, t

N

is often written as t

N

¼ t

0

e

a

, where the

factor t

0

is of the order of 10

9

–10

11

s.

3. Brownian Rotational Diffusion

If m is blocked in the lattice, along the easy axis

(y ¼ 0), the free energy is

E ¼m

0

mHcos c ð7Þ

There is no precessional motion. The equation of

motion for Brownian rotation is given by

2t

B0

dm

dt

¼

m

0

kT

m H

e

ðÞm½; t

B0

¼

3V

h

Z

kT

ð8Þ

where V

h

is the hydrodynamic volume of the particle,

and Z (N s m

2

) the kinematic viscosity of the carrier.

The longitudinal, t

B8

(t

B

), and transverse, t

B>

, relax-

ation times are given by

t

B8

¼

t

B0

x 2LðxÞxL

2

ðxÞ

LðxÞ

t

B>

¼

t

B0

2LðxÞ

x LðxÞ

ð9Þ

with

x ¼

m

0

mH

kT

where LðxÞ¼cothx 1=x is the Langevin function.

For x{1, LðxÞ¼x=3, so t

B8

¼ t

B>

¼ t

B0

. For xc1,

LðxÞ¼1 1=x and t

B8

¼ t

B>

=2 ¼ t

B0

=x. Equations

(7)–(9) also apply to the solid-state process (with t

N0

replacing t

B0

) if the influence of the anisotropy is

negligible (HcH

K

).

4. Behavior in Zero Field

A moment rotating by both processes has the effec-

tive relaxation time t

eff

given by

1

t

eff

¼

1

t

N

þ

1

t

B

ð10Þ

so the process with the shorter time is dominant. In

general, t

N0

ot

B0

, implying a critical volume V

c

satis-

fying t

N

¼ t

B

(e.g., for t

N0

=t

B0

¼ 10

2

and H ¼ 0,

V

c

E8 kT K

1

). Smaller particles will relax mostly by

Ne

´

el and larger ones by Brownian process. In a

zero field, t

N

is in the range of approximately 10

10

–

10

20

s, and t

B

of 10

8

–10

4

s, so t

eff

is in the range

198

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties

10

10

–10

4

s. A moment will appear blocked or time-

averaged to zero depending on whether t

eff

is longer

or shorter, respectively, than the measuring time, t

m

.

Every moment is time-averaged on the scale for d.c.

magnetization measurements, where t

m

is typically

1–100 s, and so a ferrofluid has no spontaneous mag-

netization. Moreover, after the removal of the field

the system is demagnetized within a time t{t

m

,so

ferrofluids are intrinsically perfectly reversible in

terms of their d.c. magnetic properties. If particle ro-

tation is frozen out, the relaxation time can reach

a geological scale. Under given experimental (t

m

; T)

conditions, a particle can appear unmagnetized

(t

N

ot

m

) or magnetized (t

N

4t

m

) depending on its

size and anisotropy (KV).

5. D.c. Magnetization and Initial Susceptibility

When the measuring time is longer than the relaxa-

tion time, the system is at thermodynamic equilibri-

um and Boltzmann statistics can be applied. If

t

B

ot

N

(t

B

ot

N

ot

m

or t

B

ot

m

ot

N

), the Ne

´

el relax-

ation is of no consequence and Eqn. (7) leads to the

magnetization given by

M ¼

M

s

R

N

0

cos c e

E=kT

sin c dc

R

N

0

e

E=kT

sin c dc

¼ M

s

LðxÞð11Þ

If t

N

ot

B

(ot

m

), which can occur only in small fields,

the system is at equilibrium on the Brownian time

scale (Eqn. (3), MðcÞ); the easy axis orientation ( c)

is changed after a Brownian event and so the mag-

netization at global equilibrium will be M ¼

1

2

R

p

0

MðcÞsincdc, which reduces for x{1to

M ¼ M

s

x=3. For xc1, there is no Ne

´

el relaxation

(H4H

K

) and M ¼ M

s

ð1 1=xÞ as a first approxi-

mation. Langevin’s law of paramagnetism describes

the result in each case. By analogy with spins, the

equilibrium behavior is called superparamagnetic.

The initial (low-field) susceptibility follows a Curie

law

m

0

M

s

VH

kT

{1; w

0

¼

M

H

¼

m

0

M

2

s

V

3kT

ð12Þ

If there are n similar particles per unit volume in

the sample, the sample magnetization is M

n

¼ nM.

In practice, it is necessary to take the size distribution

into account. Experimental devices measure the mag-

netic moment, so M

n

¼ C

v

/MS, where C

v

is the

volume fraction of particles, and M

hi

the average

particle magnetization given by

M

hi

¼

1

Z

Z

N

0

MðVÞVf ðVÞdV

Z ¼

Z

N

0

Vf ðVÞdV ð13Þ

where f ðVÞ is the volume distribution function. If all

particles satisfy the conditions for the low- and high-

field approximations of the Langevin function, the

magnetization is given by

low field M

hi

¼

m

0

HM

2

s

3kTZ

Z

N

0

V

2

f ðVÞdV ð14Þ

high field Mhi¼M

s

1

kT

m

0

HM

s

Z

ð15Þ

where M

s

is the average intrinsic magnetization. The

data exhibit no remanence and coercivity and show

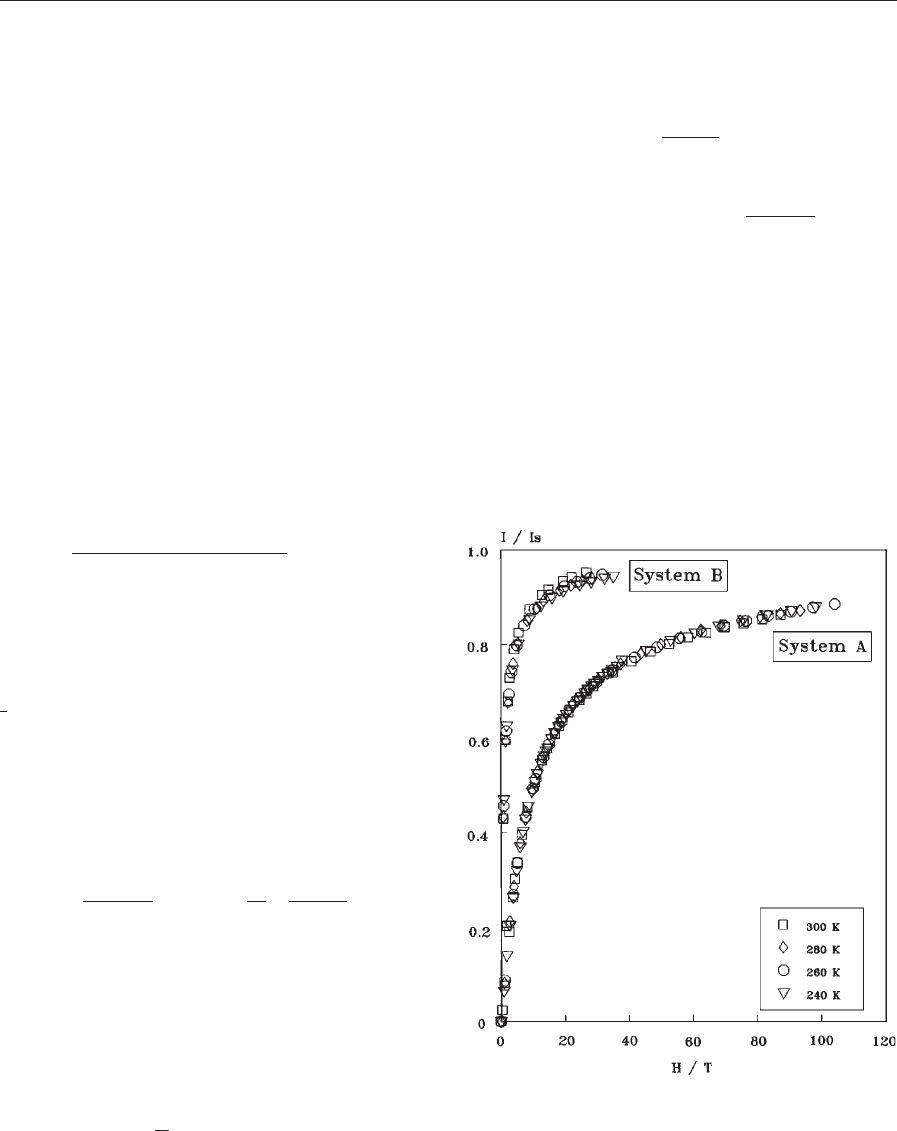

H/T superposition (Fig. 1). In principle, one can

make use of the magnetization curve to determine the

parameters of the size distribution.

Below the melting temperature of the carrier, the

moments will gradually block with decreasing tem-

perature, according to the distribution of energy

barriers. A blocking temperature T

B

is defined for a

particle of volume V as the temperature at which

t

N

¼ t

m

. In very small fields, T

B

¼ KV=klnðt

m

=t

0

Þ for

ac1. If the easy axes are randomly oriented, for

Figure 1

Thermal dependence of reduced magnetization curves of

magnetite ferrofluids. Median particle diameter (A)

4.8 nm; (B) 9.6 nm. (Reprinted with permission from

Williams et al. 1993; r Elsevier Science B.V.)

199

Ferrofluids: Magnetic Properties