Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the magnetization reversal in fields along the hard axis

and is responsible for the formation of domains. The

model of homogeneous magnetization of ideal single-

domain films is no longer applicable. The fluctuations,

j, of the magnetization cause magnetic divergencies,

leading to intrinsic demagnetizing fields. Furthermore,

exchange energy has to be taken into account. Assum-

ing a two-dimensional thin film with infinite diameter,

the total energy density depends on the site r

-

:

eðr

-

Þ¼e

H

þ e

K

u

þ e

d

ðr

-

Þþe

ex

ðr

-

Þþe

loc

ðr

-

Þð4Þ

and is now the sum of the Zeeman energy e

H

, the uni-

axial anisotropy energy e

K

u

, the intrinsic demagnetizing

energy e

d

( r

-

), the exchange energy e

ex

( r

-

), and the

local energy e

loc

( r

-

).

Instead of Eqns. (1) and (2), the following varia-

tional problems have to be solved. For the equilib-

rium state:

d

ZZZ

eðr

0

-

ÞdV

0

¼ 0 ð5Þ

and for the effective field:

h

eff

ðr

-

Þ¼

1

2K

u

d

2

ZZZ

eðr

0

-

ÞdV

0

ð6Þ

Solving Eqn. (5) first gives the mean direction j

0

of

the magnetization, which is the same as in the single-

domain theory.

Furthermore, solution of Eqn. (5) leads to a quan-

titative description of the ripple angle, j, and the rip-

ple wavelength, l. The r.m.s. value

ffiffiffiffiffiffi

j

2

q

depends on

the local anisotropies and the applied field; l depends

on the exchange constant and the applied field. On

decreasing the applied field H from saturation towards

the Stoner–Wohlfarth astroid, both the ripple angle,

j, and the ripple wavelength, l, increase (Fig. 5).

Solution of Eqn. (6) leads to a quantitative de-

scription of the intrinsic demagnetizing field caused

by the ripple (Hoffmann 1966). The effective intrinsic

demagnetizing field is aligned parallel or antiparallel

to the mean magnetization (Fig. 6). This oscillation

causes local instabilities as soon as h

eff

( r

-

) ¼0, lead-

ing to ripple blocking. This is most important for

domain formation owing to the existence of the rip-

ple. Blocking means that the mean direction of the

magnetization no longer follows the Stoner–Wohlf-

arth single-domain behavior. The film splits into

domains and hysteresis is observed.

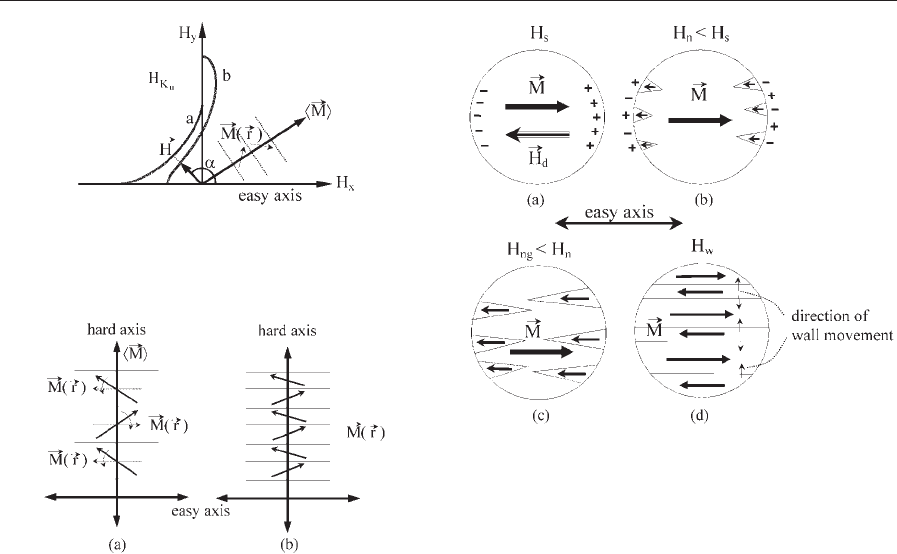

The blocking curve is now the critical curve (Fig. 7)

for magnetization reversal in thin films. On increasing

the reversed applied field, the field vector can never

approach the Stoner–Wohlfarth astroid (curve a) be-

fore crossing the blocking curve (curve b). This is a

fundamental statement of ripple theory. The mag-

netization of a real film with uniaxial anisotropy can

never be switched by coherent rotation. The magnet-

ization breaks up into domains. Magnetization re-

versal is completed by domain wall motion. This

theoretical prediction has been confirmed by many

experiments. The Stoner–Wohlfarth model can be

applied only to the region outside the blocking curve.

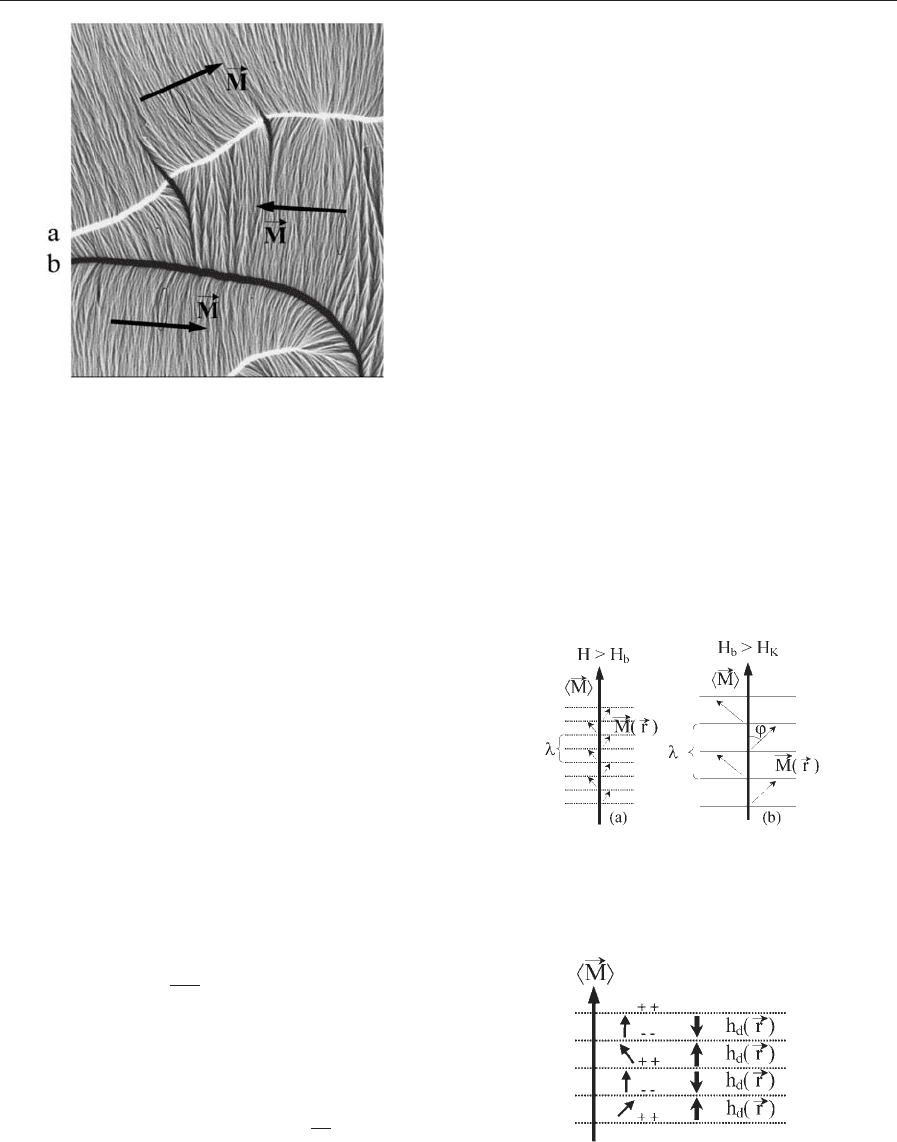

Figure 5

Magnetization ripple: (a) free ripple state; (b) ripple at

blocking field H

b

.

Figure 4

Lorentz image with magnetization ripple, Bloch wall,

and cross-tie wall (courtesy of J. Zweck).

Figure 6

Intrinsic demagnetizing field of the ripple.

1250

Thin Films: Domain Formation

3. Magnetization Reversal in Fields Along the

Hard Axis

Magnetization reversal along the hard or easy axis is

of special interest. In the case of high-quality films

(low local anisotropies), the magnetization loop in

the hard axis direction may appear as in Fig. 3(b) as a

straight line. In this case the intrinsic demagnetizing

field is small. The ripple wavelength at blocking,

which determines the domain width, is large. Each

domain then behaves like a Stoner–Wohlfarth single

domain. Reversal occurs by clockwise and counter-

clockwise rotation of the magnetization within each

domain (Fig. 8(a)). The remanence is zero.

In the case of larger local anisotropies the intrinsic

demagnetizing field is stronger. The ripple wave-

length at blocking is smaller (Fig. 8(b)). Magnetiza-

tion reversal within the domains is affected by the

demagnetizing field. Hysteresis is observed. The re-

manence is larger than zero.

4. Magnetization Reversal in Fields Along the

Easy Axis

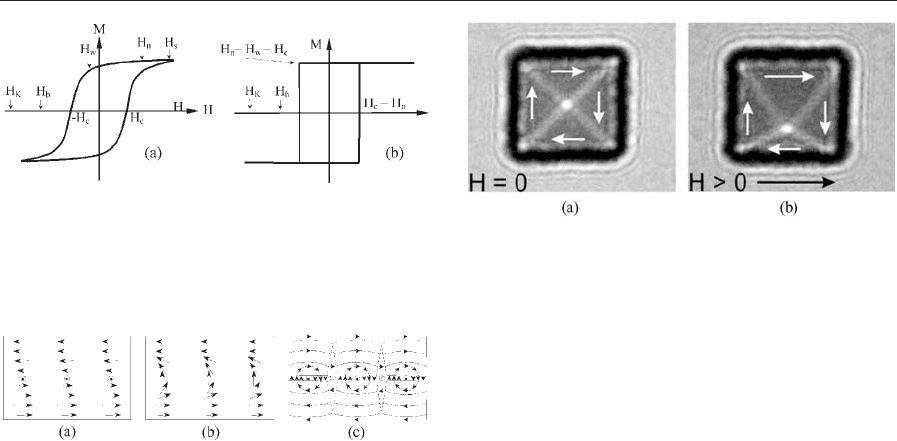

During magnetization reversal along the easy axis

some more effects have to be discussed. Owing to the

finite size of the films, at saturation magnetic poles at

the edge of the film create an external demagnetizing

field H

d

(Fig. 9(a)), which need not be discussed dur-

ing hard axis reversal.

The demagnetizing field is antiparallel to the mag-

netization. It is strongest at the film edge. Decreasing

the applied field below the saturation field leads to

nucleation of reversed domains at the nucleation field

H

n

(Fig. 9(b)). This reduces the total demagnetizing

field and consequently the demagnetizing self-energy.

On decreasing the applied field further, the re-

versed nuclei grow (at H

ng

) (Fig. 9(c)) and finally

form domains (Fig. 9(d)). The magnetization reversal

is finalized by domain wall movement that starts at

H

w

. The reversal always starts with nucleation at H

n

.

The shape of the magnetization loop depends on the

strengths of H

n

, H

ng

, and H

w

. The ripple is present in

all cases but the mentioned fields dominate the do-

main formation and the magnetization reversal, since

these fields are effective before ripple blocking occurs.

Two characteristic types of magnetization loops

are observed, depending on the geometry and quality

of the film:

(i) H

n

4H

ng

4H

w

4H

c

, which leads to a magnet-

ization loop in the easy axis direction as shown in

Fig. 10(a); and

(ii) H

n

oall other fields, which leads to a magnet-

ization loop as shown in Fig. 10(b); in this case the

applied field H has to be reversed from the saturation

direction to nucleate the reversed domains, which

immediately grow to larger domains and saturate the

magnetization by domain wall movement.

Figure 7

Critical curves for magnetization reversal: (a) Stoner–

Wohlfarth astroid; (b) blocking curve.

Figure 8

Magnetization ripple during reversal along the hard

axis. Ripple at the blocking field. Film with (a) low local

anisotropies and (b) large local anisotropies.

Figure 9

Stages of magnetization reversal along the easy axis: (a)

saturation in applied field H

s

; (b) nucleation of reversed

domain at decreasing applied field; (c) growth of the

nuclei; (d) formation of walls and wall movement.

1251

Thin Film s: Domain Formation

The magnetization loop of Fig. 10(b) is similar to

that along the easy axis of the Stoner–Wohlfarth sin-

gle-domain theory (Fig. 2(a)) where magnetization

reversal is given by coherent switching. In real films

coherent switching at H

K

u

can never occur, as ex-

plained by the blocking curve (Fig. 7). Domains are

formed and magnetization reversal occurs by domain

wall movement. This is very clearly seen, since

7H

c

7o7H

K

u

7 in all cases. The magnetization reversal

in isotropic films with zero uniaxial anisotropy is the

same as described above for the easy axis reversal.

In general, the single-domain theory is valid only

outside the blocking curve (Fig. 7). The films can be

used as sensors without hysteresis, as long as the

magnetic field vector does not cross the blocking

curve. Coherent switching is impossible.

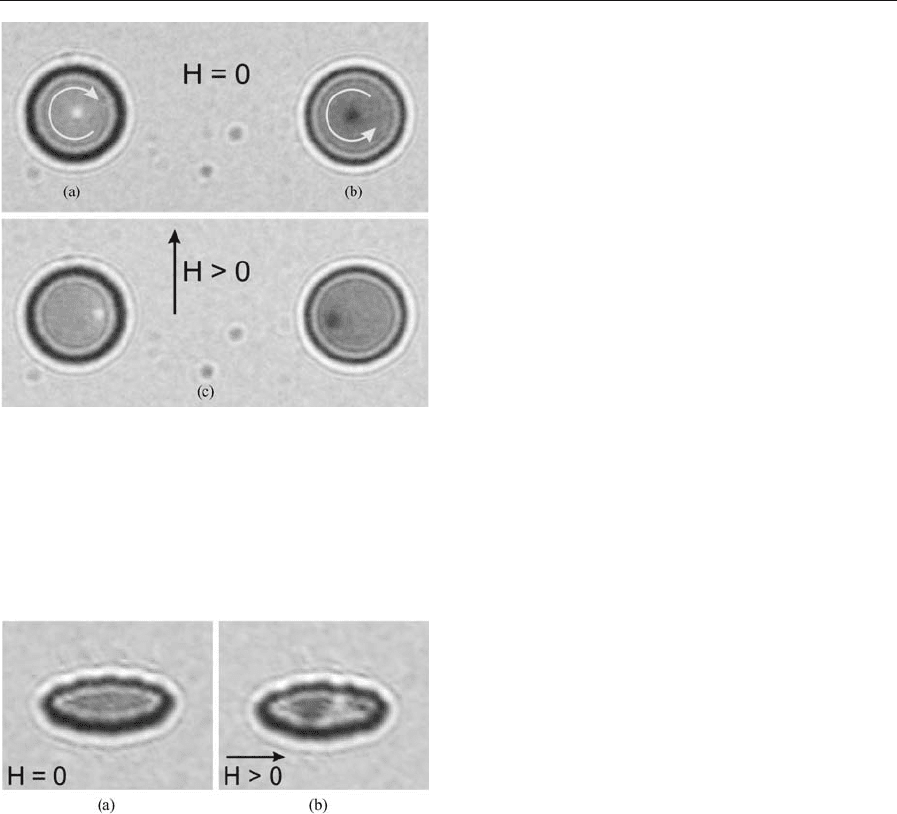

5. Domain Walls

Three types of walls are observed in thin films, de-

pending on the film thickness (Kittel 1949, Hubert

and Scha

¨

fer 1998, Middelhoek 1961). Examples are

given below for permalloy films.

(i) Bloch wall, film thickness d450 nm (Fig. 11(a)).

Inside of the walls the magnetic moments rotate

around the normal of the walls, avoiding magnetic di-

vergences and stray fields parallel to the film plane.

Stray fields perpendicular to the film plane result from

magnetic poles at the film surface.

(ii) Ne

´

el wall, film thickness do25 nm (Fig. 11(b)).

For thinner films the magnetic self-energy of poles at

the film surface is too strong. Within the wall the

magnetic moments rotate in the film plane, avoiding

the magnetic poles at the surfaces. Instead, the wall

creates magnetic divergencies, which increase the wall

energy.

(iii) Cross-tie wall, film thickness B25–50 nm

(Fig. 11(c)). This type of wall is a transition between

the Ne

´

el and Bloch walls.

6. Magnetization Reversal in Nanostructures

Domain formation in nanostructures is governed by

the external demagnetizing field from the film edge.

In the remanent state domains are formed to avoid

the demagnetizing field.

6.1 Rectangular Nanostructures

Rectangular nanostructures show in the remanent

state the ideal Landau–Lifshitz domain configuration

that is shown in the Lorentz image of Fig. 12(a).

Applying a magnetic field causes an increase of the

domain with magnetization parallel to the field and a

decrease of the domain with antiparallel magnetiza-

tion. The vortex in the center of the film is shifted

perpendicular to the applied field (Fig. 12(b)).

6.2 Circular Nanostructures

To avoid the demagnetizing field from the edges of the

circular nanostructures in the remanent state the mag-

netization forms a circular flux closure with a vortex

in the center of the nanostructure. Figures 13(a) and

(b) show the Lorentz image of rotation of the mag-

netization. Increasing an applied field shifts the vortex

perpendicular to the applied field with respect to the

film edge (Fig. 13(c)). At the saturation field H

s

the

vortex collapses. This saturation field is larger than

the demagnetizing field H

d

at saturation. Decreasing

the applied field to zero again leads to circular flux

Figure 10

Magnetization loops dominated (a) by the field

necessary for wall movement and (b) by the nucleation

field.

Figure 11

Domain walls in thin films: (a) Bloch wall; (b) Ne

´

el wall;

(c) cross-tie wall.

Figure 12

Landau–Lifshitz configuration of domains of a squared

nanostructure, observed by Lorentz microscopy: (a)

remanence; (b) in an applied field (courtesy of M.

Schneider).

1252

Thin Films: Domain Formation

closure with a vortex in the center of the structure

(see Figs. 13(a) and (b)).

6.3 Elliptical Nanostructures

The shape anisotropy of elliptical nanostructures

leads to an easy axis along the major axis. After

saturation along the easy axis the structure remains in

a single-domain state at zero field (Fig. 14(a)). On

applying a reverse field the magnetization breaks up

into domains (Fig. 14(b)). Saturation in the reverse

field occurs by domain wall motion. These structures

are of interest for magnetic storage. For this purpose

the formation of domains during magnetization re-

versal has to be avoided. Much work is in progress to

overcome this reversal problem.

7. Conclusion

The interest in ferromagnetic films is rapidly growing

because of their application as field sensors in various

modes, as magnetic storage material for floppy disks,

as nanostructures in MRAMs, and as giant magnetic

resistance elements in many applications. In cases of

single-domain behavior stability at remanence and

after switching the magnetization from one stable

state to another is desired. Difficulties arise because

of domain formation in the films and nanostructures.

This article shows that in any nonideal soft magnetic

film domain formation is unavoidable. Future inves-

tigations will try to overcome this problem instead of

neglecting it.

See also: Longitudinal Media: Fast Switching; Mag-

nets, Soft and Hard: Domains; Magnetic Films:

Anisotropy; Magnetic Layers: Anisotropy; Mono-

layer Films: Magnetism

Bibliography

Cohen M S 1969 In: Chopra K L (ed.) Thin Film Phenomena.

McGraw-Hill, New York, 608 ff

Craik D J, Tebble R S 1965 Ferromagnetism and Ferromagnetic

Domains. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Hoffmann H 1966 Stray fields in thin magnetic films. IEEE

Trans. Magn. MAG 2, 566–70

Hoffmann H 1968 Theory of magnetization ripple. IEEE Trans.

Magn. MAG 4, 32–8

Hubert A, Scha

¨

fer R 1998 Magnetic Domains. Springer, Berlin,

p. 11 ff

Kittel C 1949 Physical theory of ferromagnetic domains. Rev.

Mod. Phys. 21, 541–83

Middelhoek S 1961 Ferromagnetic domains in thin Ni–Fe films.

Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam

Prutton M 1964 Thin Ferromagnetic Films. Butterworth, Wash-

ington, DC

Stoner E C, Wohlfarth E P 1948 A mechanism of magnetic

hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A250,

599–642

H. Hoffmann

Universita

¨

t Regensburg, Germany

Thin Films: Giant Magnetostrictive

Interest in giant magnetostrictive materials in thin film

form has grown rapidly over the past few years, owing

to their potential as actuators for powerful trans-

ducer systems in microsystems, e.g., laser scanners,

Figure 13

Circular nanostructures (height 15 nm, diameter 600 nm)

observed by Lorentz microscopy. The bright and dark

spots are vortices. (a) Counterclockwise flux closure at

remanence, vortex in the center of the circle. (b)

Clockwise flux closure at remanence. (c) Applied field

~

H:

shift of the vortices perpendicular to

~

H towards the edge

of the nanostructure (courtesy of M. Schneider).

Figure 14

Lorentz microscopy image of elliptical nanostructures:

(a) at remanence after saturation along the major axis;

(b) in applied reverse field (courtesy of M. Schneider).

1253

Thin Film s: Giant Magnetostrictive

micropumps, and ultrasonic motors (Quandt 2000).

The development of the corresponding room temper-

ature giant magnetostrictive thin film materials is

based on rare earth–transition metal alloys. In gener-

al, the rare earth iron-based alloys offer the best

chance of developing giant magnetostriction at room

temperature or above, since the highly aspherical 4f

orbitals of the rare earths remain in an oriented state,

owing to the strong coupling between the rare earth

and the iron moments, resulting in this large room-

temperature magnetostriction.

An important task in developing giant magnetos-

trictive materials has been optimization of magneto-

striction to magnetic anisotropy ratio, in order to

attain large strains at moderate magnetic fields. In

bulk materials it was achieved by using cubic com-

pounds—the rare earth–Fe

2

Laves phases—in which

the second order anisotropy constant vanishes, also

by Tb–Dy alloying in order to compensate the fourth

order anisotropy constant (Clark 1980). In the case of

thin films, amorphous (Tb,Dy)

x

(Fe,Co)

1x

films

(Duc et al. 1996) or especially novel TbFe/FeCo

multilayers (Quandt and Ludwig 1999) represent the

most promising approaches to combine soft magnetic

and giant magnetostrictive properties.

Special attention has to be paid to the sign of the

magnetostriction. While terbium-based materials ex-

hibit positive magnetostriction, which means that this

material expands in the direction of the external field,

samarium-based materials behave in the opposite

way, thus allowing an easy design of magnetostrictive

bimorphs, which enables the realization of stress- or

temperature-compensated bending actuators while

further enhancing the overall effect.

The fabrication of giant magnetostrictive thin films

was originally realized only by PVD techniques, the

most prominently used being magnetron sputtering

(Quandt 2000) with either mosaic-type or composite

targets as well as multitarget arrangements. Other

PVD techniques include electron beam evaporation,

laser ablation and ion beam sputtering. The amor-

phous films are generally deposited onto unheated or

cooled substrates, while for crystalline films heated

substrates for a single-step process are used as an al-

ternative to a post-deposition crystallization treatment.

For applications, the orientation of the magnetic

easy axis and of the domains in the demagnetized

state is of special importance, because maximum

magnetostriction is only obtained by 90 1 rotations of

the magnetic domains while 180 1 rotations do not

result in any magnetostrictive strain. Considering

that magnetostrictive thin film actuators are in gen-

eral driven by a single magnetic field, the direction of

which is fixed in relation to the actuator and in-plane

in order to avoid large demagnetization losses, the

optimized demagnetized state should consist of do-

mains with an in-plane easy axis being oriented per-

pendicular to the driving field direction. This initial

state can be obtained by a post-deposition annealing

process under an in-plane magnetic field which is

oriented under 90 1 towards the driving field direction

(Ludwig and Quandt 2000).

Another possibility to influence the direction of the

magnetic easy axis of a magnetostrictive film is di-

rectly related to the film’s stress. Considering the

minimum of the magnetoelastic energy for an iso-

tropic ferromagnet

E

me

¼

3

2

sl

s

cos

2

a

the orientation of the magnetic easy axis (a: angle

between the directions of the magnetization and of

the application of the stress) depends on the sign of

the film stress s for a material with a given saturation

magnetostriction l

s

. This equation implies an in-

plane magnetic easy axis for a positive product sl

s

,

while a negative product results in a perpendicular

anisotropy. Therefore, in the case of positive magne-

tostrictive-like terbium-based or FeCo films, tensile

stress is required for in-plane anisotropy, whereas

negative magnetostrictive samarium-based films

should be deposited with compressive stress to result

in the same anisotropy. As the sign and the magni-

tude of the film’s stress can be controlled by the fab-

rication conditions, the thermal expansion coefficient

of the substrate, or by stress annealing, an in-plane

magnetic easy axis can be adjusted, in general, for all

thin film materials.

The in-plane magnetoelastic coupling coefficient b

or the magnetostriction l can be measured by the

common cantilevered substrate technique using the

formula of du Tre

´

molet de Lachesserie and Peuzin,

resulting in:

b ¼

a

L

h

2

s

h

f

E

s

6ð1 þ n

s

Þ

; l ¼

bð1 þ n

f

Þ

E

f

where a is the deflection angle of the cantilever as a

function of applied field, L is the free length of the

cantilever, E

s

and n

s

are the Young’s modulus and

Poisson’s ratio for the substrate, and h

s

, h

f

are the

thicknesses of the substrate and film, respectively.

In the following sections, amorphous, nanocrys-

talline and multilayered state-of-the-art giant mag-

netostrictive materials in thin film form with positive

and negative magnetostriction and applications of

these materials are discussed.

1. Amorphous Films

Use of amorphous materials is an important

approach to lowering macroscopic anisotropy. In

amorphous magnetic rare earth–iron alloys, the con-

tribution of the rare earth–iron interaction results in

the formation of a sperimagnetic structure with an

ordering temperature above room temperature. In

the case of positive magnetostrictive materials, TbFe

thin films have been fabricated in a wide composition

1254

Thin Films: Giant Magnetostrictive

range. It was found that increasing the rare earth

content compared to the Laves phase composition

results in the highest low-field magnetostriction in

amorphous thin film materials. Assuming the same

local environment in the amorphous compared to the

crystalline state, a further approach to reduce the

remaining anisotropy should be achievable by Tb/Dy

substitution, which was investigated for a wide com-

position range for rare earth–iron or rare earth–

cobalt thin film materials. This approach leads to a

further reduction in the magnetic saturation field, but

the lower Curie temperature due to the dysprosium

alloying leads to a significant reduction in the satu-

ration magnetostriction resulting in no or only a very

small gain in low-field magnetostrictive strain of these

ternary films.

Since the Curie temperature of amorphous TbFe is

still quite low and is thus detrimental to giant mag-

netostriction to be obtained at higher temperatures,

another interesting approach is related to the amor-

phous TbCo or TbFeCo alloys. Although the crys-

talline Laves phase TbCo

2

orders below 300 K, the

ordering temperatures in amorphous TbCo alloys are

raised up to 600 K depending on the composition,

owing to a strongly ferromagnetically coupled cobalt

sublattice with a sperimagnetic structure. In partic-

ular, amorphous films of the system Tb–Dy–Fe–Co

exhibit very high room temperature magnetostrict-

ions, exceeding 1000 10

6

. Comparison with other

amorphous terbium-based thin film materials is

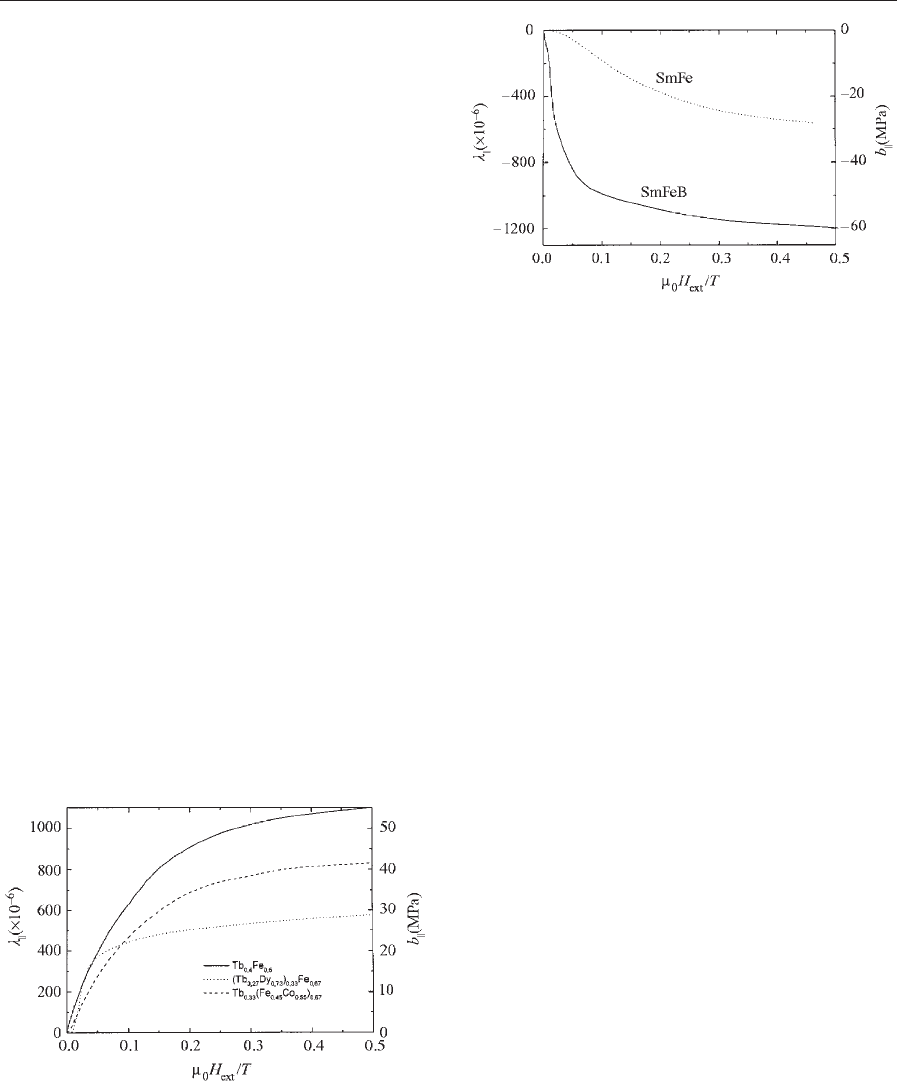

shown in Fig. 1.

While SmFe

2

bulk materials are normally not con-

sidered as actuator materials, owing to the tensile

stress required in these materials in order to achieve a

suitable alignment of the magnetic domains, this sit-

uation is different in thin film bending transducers,

which can easier be stressed with different signs.

Therefore, amorphous Sm–Fe and Sm–Fe–B thin

films have been investigated over a wide composi-

tional range, showing interesting giant magnetostrict-

ion at low external fields, especially in the case of

Sm–Fe–B with a boron content of approximately 0.8

at.% (Lim et al. 1998), which is shown in Fig. 2 in

comparison to an amorphous SmFe thin film.

2. Nanocrystalline Materials

The major drawback of all amorphous materials are

their low Curie temperatures, leading to a limited

temperature range of use and to large temperature

coefficients of the magnetostriction at room temper-

ature. Since the Laves phase TbFe

2

orders at 711 K

(Clark 1980), crystallized films of the composition

(Tb

0.3

Dy

0.7

)Fe

2

have been investigated in some detail.

In general, it has been found that crystallization is

accompanied by a coercivity of at least 70 mT, thus

requiring large magnetic driving fields. A possibility

to overcome these limitations is related to the control

of the grain size of the magnetic thin film material, as

the random anisotropy model predicts a decrease of

the coercivity with the grain size provided that the

grain size is smaller than the ferromagnetic exchange

length (Winzek et al. 1999).

Therefore, giant magnetostrictive materials with

nanocrystalline grain structure should allow the com-

bination of high Curie temperatures with soft mag-

netic properties. In particular, three approaches to

realize a nanocrystalline grain structure have been

reported: control of the crystallization temperature,

addition of additives to enhance grain nucleation,

and the use of multilayer structures to limit the grain

growth in normal direction. The most promising re-

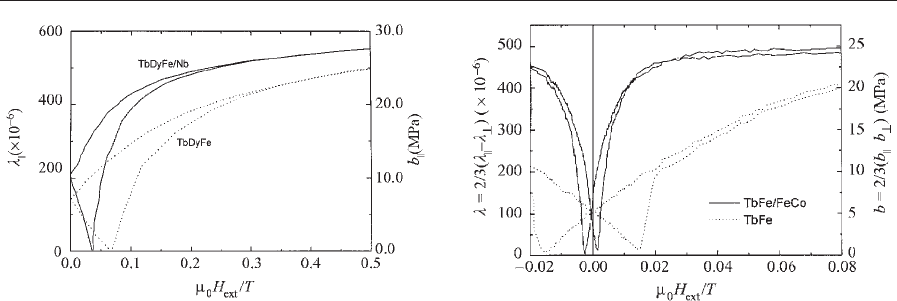

sult has been obtained for TbDyFe/Nb multilayers

having a Curie temperature of 560 K and a saturation

magnetostriction of 550 10

6

. Their hysteresis is

significantly reduced compared to crystalline single

Figure 1

In-plane magnetostriction and magnetoelastic coupling

coefficient of amorphous Tb

0.4

Fe

0.6

,

(Tb

0.27

Dy

0.73

)

0.33

Fe

0.67

, and Tb

0.33

(Fe

0.45

Co

0.55

)

0.67

films.

Figure 2

In-plane magnetostriction and magnetoelastic coupling

coefficient of amorphous Sm

0.4

Fe

0.6

and

Sm

0.368

Fe

0.626

B

0.006

films.

1255

Thin Film s: Giant Magnetostrictive

layer materials (Fig. 3), but still reaches 35 mT under

optimized preparation conditions.

3. Multilayers

Since the magnetic saturation field is proportional to

the ratio of the anisotropy and the saturation mag-

netization, an alternative approach is based on an

increase of the saturation magnetization of these ma-

terials. The amorphous rare earth transition metal

materials used up to now have rather low magneti-

zations, owing to their ferrimagnetic nature. For the

compositions of interest the rare earth moments

dominate and thus any decrease of their content will

further reduce the magnetization, while an increase

results in a lowering of the Curie temperature and

consequently a lowering of the room temperature

magnetization. However, using multilayers it is pos-

sible to engineer new composite materials with prop-

erties which overcome these limitations (Quandt and

Ludwig 1999).

To create such a composite, two materials have to

be combined: one material is the giant magnetos-

trictive amorphous TbFe alloy, while the other is

magnetically soft and has a very high magnetization

and, preferably, a considerable magnetostriction itself

(e.g., FeCo). Fabricating these layers with thicknesses

smaller than the ferromagnetic exchange length and

the domain wall width, domain wall formation at the

interfaces is prevented and the magnetic properties

of such an exchange-coupled multilayer system are

determined by the average of those of each individual

layer. Although it was found that the layers couple

anti-parallelly, an enhancement of the overall mag-

netization is achievable for certain thickness ratios.

Together with the reduction in anisotropy this in-

crease in magnetization results in a significant

reduction in the magnetic saturation field. Figure 4

compares the low field magnetoelastic coupling coef-

ficient of an optimized TbFe/FeCo multilayer with a

state-of-the-art amorphous TbFe single layer film.

Furthermore, these types of multilayers show two

effects which are of interest for the realization of

smart actuators: both a significant change of the

Young’s modulus and of the electrical resistivity with

the magnetic field. The Young’s moduli of the mu-

lilayers exhibit a distinct increase with the applied

magnetic field, of approximately 20% in the case of

an annealed TbFe/FeCo multilayer, while this effect

is smaller and requires higher magnetic fields in the

case of the corresponding amorphous TbFe single-

layer materials. The magnetoresistive effect is ap-

proximately 0.2% being developed in the same field

range as the films’ magnetostriction.

4. Applications

Giant magnetostrictive materials in thin film form

have predominantly been used as various micro-ac-

tuators for applications in microsystem technology

(Ludwig and Quandt 2000). Their working principle

is based on a bending transducer which consists of a

film/substrate compound with the substrate being, in

general, non-magnetostrictive. Different geometries

and boundary conditions are common, the most im-

portant being cantilevers, membranes and plates.

Upon magnetization the magnetostriction in the film

causes the film/substrate compound to bend, similar

to the bending of a bimetallic transducer. Commonly,

the most important feature of these micro-actuators

is their remote-controlled operation. In the following,

some examples of these magnetostrictive thin film

transducers are explained in more detail.

In the case of cantilevers different applications have

been realized, normally by using silicon micro-ma-

chining for the fabrication of the cantilevers. The large

Figure 3

In-plane magnetostriction and magnetoelastic coupling

coefficient of nanocrystalline (Tb

0.27

Dy

0.73

)

0.33

Fe

0.67

films and (Tb

0.27

Dy

0.73

)

0.33

Fe

0.67

/Nb multilayers.

Figure 4

Low-field magnetostriction and magnetoelastic coupling

coefficient of Tb

0.4

Fe

0.6

/Fe

0.5

Co

0.5

multilayers in

comparison to Tb

0.4

Fe

0.6

amorphous single layers.

1256

Thin Films: Giant Magnetostrictive

bending or deflection of these cantilevers was applied

for fluid jet deflectors controlling up to 500 mls

1

,for

magnetic field measurements by detecting the deflec-

tion of the cantilever optically, as well as for optical

two-dimensional micro-mirrors which employ bending

and torsional vibrations driven by two differently ori-

ented magnetic fields. Furthermore, special attention

was paid to the development of thermal drift-free

actuators either realized by a special design of the

micromachined substrate or by combining positive

and negative magnetostrictive materials in a bimorph

structure.

Magnetostrictive membranes have been used for

fluidic micro-components such as micro-valves or

micro-pumps, whereas the deflection of the mem-

brane is used either to close or to open the valve

outlet or to induce a pressure rise in the pumping

chamber. Free plates with magnetostrictive coatings

have been employed for the realization of travelling

machines or for ultrasonic motors. Both linear and

rotating standing wave motors were realized with

micro-machined silicon or titanium substrates using a

propulsion mechanism of vibrating teeth on a friction

layer. The ultrasonic motors were operated by a.c.

magnetic fields in combination with a magnetic bias

field.

As a completely different application, giant mag-

netostrictive thin films can be used in scanning probe

microscopy for magnetic field imaging. This tech-

nique has been demonstrated in the case of the mag-

netic field distribution of a hard-disk read–write head

by coating this device and measuring the magnetic

field induced change in the thickness of the coating

due to the magnetostriction.

These different applications demonstrate the po-

tential that giant magnetostrictive thin film materials

have for the realization of micro-actuators and

micro–sensors. It is expected that further application

areas can be addressed by using the novel giant

magnetostrictive multilayers, owing to their higher

magnetostrictive susceptibility, their higher Curie

temperature and their additional features, e.g., their

change of resistivity and Young’s modulus in a mag-

netic field.

See also: Magnetoelastic Phenomena; Magneto-

strictive Materials; Magnetoelasticity in Nanoscale

Heterogeneous Materials

Bibliography

Clark A E 1980 Magnetostrictive rare earth–Fe

2

compounds.

In: Wohlfarth E P (ed.) Ferromagnetic Materials. Elsevier,

Amsterdam, Vol. 1, pp. 531–86

Duc N H, Mackay K, Betz J, Givord D 1996 Giant magne-

tostriction in amorphous (Tb

1x

Dy

x

)(Fe

0.45

Co

0.55

)

y

films. J.

Appl. Phys. 79, 973–6

Lim S H, Choi Y S, Han S H, Kim H J, Shima T, Fujimori H

1998 Magnetostriction of Sm-Fe and Sm-Fe-B thin films

fabricated by RF magnetron sputtering. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 189, 1–8

Ludwig A, Quandt E 2000 Giant magnetostrictive thin films for

applications in microelectromechanical systems. J. Appl.

Phys. 87, 4691–5

Quandt E 2000 Giant magnetostrictive thin film technologies.

In: Engdahl G (ed.) Handbook of Giant Magnetostrictive

Materials. Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 323–43

Quandt E, Ludwig A 1999 Giant magnetostrictive multilayers.

J. Appl. Phys. 85, 6232–7

Winzek B, Hirscher M, Kronmu

¨

ller H 1999 Crystallization of

sputter-deposited giant-magnetostrictive TbDyFeM (M ¼Mo,

Zr) films and multilayers. J. Alloys Comp. 283,78

E. Quandt

Stiftung Caesar, Bonn, Germany

Transition Me tal Oxides: Magnetism

For practical applications the most important mag-

netic transition metal oxides are ferrites. In addition,

manganites with perovskite structure and chromium

dioxide are also important. Oxides in which magnet-

ism is connected with the presence of f electrons are

discussed elsewhere (see Localized 4f and 5f Moments:

Magnetism).

A convenient feature of ferrites is that their mag-

netic properties can be well controlled. This is con-

nected with the fact that the magnetic part of the free

energy has a good approximation in a single ion char-

acter, i.e., it is a sum of the contributions of individual

ions present in the system. As a rule there are several

crystallographic sublattices occupied by cations with a

large number of possible combinations of cation types

and concentrations. By choosing the proper combina-

tion the desired properties may be then achieved.

There are numerous reviews of magnetism and the

properties of transition metal oxides. A good review

with an accent on applications was written by

McCurrie (1994). Ferrites with the spinel structure

were considered by Krupic

ˇ

ka and Nova

´

k (1982) and

Brabers (1995), while those with the garnet and mag-

netoplumbite structure were discussed by Winkler

(1981) and Kojima (1982), respectively. Recent ex-

perimental results for the mixed valence manganites

were reviewed by Ramirez (1997).

1. Basic Interactions of Loc alized Electrons

In most of the magnetic oxides the 3d electrons of the

iron group transition metal ions may be treated as

localized. The exceptions are usually connected with

the mixed valence, i.e., with the presence of two dif-

ferent valence states of the same atom on crystallo-

graphically equivalent sites. Even in these cases,

however, the localized picture provides a convenient

starting point. The interactions important for the

1257

Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism

magnetism of systems with localized 3d electrons are

discussed below.

1.1 Intra-atomic Coulomb Interaction

This interaction makes the occupation of an orbital

state by two electrons with opposite spins energetically

unfavorable. A consequence is the First Hund’s rule

according to which the ground state of a free ion cor-

responds to the maximal total spin S. Between terms

having the same S, the term with the maximum total

angular momentum L is energetically most stable

(Second Hund’s rule). The energy intervals between

terms characterized by their L and S values are of the

order of electron volts. In particular the ground state

of the Fe

3 þ

ion is

6

S (S ¼5/2, L ¼0) and the first

excited term

4

G (S ¼3/2; L ¼4) is at B4eV.

1.2 Crystal and Ligand Field

In crystals the electrons of a magnetic ion are sub-

jected to the electrostatic crystal field and due to the

covalency the 2s and 2p electrons of oxygen ligands

are transferred to the empty states of the magnetic

ion. Both these effects lead to the splitting of the en-

ergy levels of the ion. The corresponding interaction

has a single electron character and it is described by

an effective Hamiltonian:

#

H

CF

¼

X

2l

k¼0

X

k

q¼k

B

k;q

#

t

k;q

ð1Þ

where B

k,q

is the crystal field coefficient and t

ˆ

k,q

is the

one electron irreducible tensor operator, which can

be expressed in terms of the electron orbital momen-

tum operator l

ˆ

%

. The Hamiltonian H

ˆ

CF

reflects the

local symmetry of the ion site. For the d electrons

(l ¼2), in the important case of the octahedral sym-

metry, Eqn. (1) reduces to:

#

H

CF

¼

B

4

60

½35

#

l

4

z

30lðl þ 1Þ

#

l

2

z

þ 25

#

l

2

z

6lðl þ 1Þþ3l

2

ðl þ 1Þ

2

þ

5

2

ð

#

l

4

þ

þ

#

l

4

Þ ð2Þ

which splits a quintuplet of d-orbital states into a

lower lying triplet, denoted as t

2g

, and doublet e

g

. The

splitting between the doublet and the triplet is of the

order of electronvolts and H

ˆ

CF

is thus comparable to

the intra-atomic Coulomb interaction. In the tetra-

hedral symmetry the quintuplet is again split into a

doublet e and a triplet t

2

, with the doublet having a

lower energy. If the local symmetry is lower than cu-

bic, more terms are present in H

ˆ

CF

causing additional

splitting of the orbital states.

1.3 Spin-orbit Coupling

The spin-orbit coupling is an intra-atomic relativistic

interaction, which couples the electron spin with its

orbital momentum. It may be approximated by:

#

H

ls

¼ zð l

-

s

-

Þð3Þ

For the iron group ions the spin-orbit coupling

parameter z is of the order of 1 10

2

–1 10

1

eV

and H

ˆ

ls

is thus smaller compared to the intra-atomic

Coulomb and crystal field interactions.

1.4 Vibronic Interaction, Jahn–Teller Effect

The vibronic (electron–lattice) interaction is especial-

ly important for ions, which have the orbitally de-

generate ground state in the given crystal

environment. As shown by Jahn and Teller a cou-

pling term, linear in displacement of ions (‘‘force’’),

then appears in the Hamiltonian. In the static treat-

ment, which neglects the kinetic energy of ions, the

local symmetry is then lowered by a spontaneous

distortion of the environment (static Jahn–Teller ef-

fect). The static treatment is appropriate for systems

with a large concentration of Jahn–Teller ions, where

the co-operative interaction leads to lowering of the

crystal symmetry. If a Jahn–Teller ion is isolated in

an otherwise ideal lattice, the symmetry of its envi-

ronment remains unchanged. However, in wave func-

tions the electron and lattice coordinates become

inexorably mixed, leading to a significant modifica-

tion of the behavior observed, e.g., the spin-orbit

coupling is quenched (dynamic Jahn–Teller effect).

Examples of ions exhibiting strong Jahn–Teller ef-

fects are Mn

3 þ

,Cr

2 þ

, and Cu

2 þ

ions in the octa-

hedral co-ordination and the tetrahedral Fe

2 þ

ion.

1.5 Exchange Interaction

The dominant mechanisms of the exchange interac-

tion in magnetic oxides are connected with the trans-

fer of electrons between the magnetic ions via the

intervening oxygen ligands. Such ‘‘supertransfer’’ de-

pends on the mutual orientation of the spins and on

the occupations of the electron orbitals. Owing to the

Pauli principle, the transfer can occur in the case of

half-filled orbitals only for antiparallel spins, hence

the antiparallel spin orientation is favored. This is the

strongest exchange mechanism in ferrites leading to

ferrimagnetism or antiferromagnetism. If one of the

orbitals in question is empty, transfer of electrons

with both spin orientations is allowed, but, because of

the intra-atomic exchange interaction (First Hund’s

rule), the parallel orientation is preferred. This mech-

anism thus leads to ferromagnetic ordering. A par-

ticular case of the latter interaction occurs when the

two orbital states have the same energy, as in the

manganite perovskites with mixed Mn

3 þ

–Mn

4 þ

va-

lence. The Mn

3 þ

–Mn

4 þ

pair may be treated as

Mn

4 þ

–Mn

4 þ

þe

with the Mn

4 þ

centers being

equivalent. The tendency to ferromagnetism is then

1258

Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism

strong, and the interaction is in this case called the

double exchange (e.g., Kubo and Ohata 1972).

The exchange interactions listed above are isotrop-

ic and the corresponding effective Hamiltonian has

the Heisenberg form:

#

H

ex

¼

X

i

X

jai

J

ij

~

^

S

i

~

^

S

j

ð4Þ

For the double exchange this form is only a rough

approximation, because the biquadratic and higher-

order terms are important too. The exchange integral

J

ij

is a sensitive function of the angle between the M

i

-

oxygen and the M

j

-oxygen bonds in the M

i

-oxygen-

M

j

triad and it also depends on the orbital states in

question. In particular, if either the M

i

or the M

j

cation has an orbitally degenerate state, J

ij

must be

treated as an operator in the orbital space.

In combination with the spin-orbit and crystal-

field terms the exchange interaction (Eqn. (4)) yields

anisotropic terms in the effective Hamiltonian, which

may be expressed in the pseudodipolar or/and

Dzyaloshinski–Moriya form:

#

H

psdip

¼

~

^

S

i

%

T

~

^

S

j

;

#

H

DM

¼ D½

~

^

S

i

;

~

^

S

j

ð5Þ

where T

%

is a traceless tensor (e.g., Kanamori 1963).

2. Crystal and Magnetic Structure

A convenient representation of the crystal structures

of the magnetic oxides is provided by the intercon-

nected polyhedra as showed in Figs. 1(a)–(d). The

centers of the polyhedrons (tetrahedrons, octahe-

drons, dodecahedrons, or bipyramids) are occupied

by the cations, while the oxygen ligands are situated

in their corners.

2.1 Spinels

Spinel ferrites MFe

2

O

4

have a cubic crystal symmetry

with eight formula units in the unit cell. There are

two cation sublattices—tetrahedral (A) and octahe-

dral (B). In spinel ferrites with a normal structure

(e.g., Zn

2 þ

[Fe

2

3 þ

]O

4

)M

2 þ

ions occupy the A sublat-

tice, while the B sublattice is filled by the Fe

3 þ

ions.

In the inverse spinel ferrites the M

2 þ

ions are in the B

sublattice (M ¼Ni, Co, or Fe). For M ¼Mn, Mg, or

Cu the M ions are in both the A and B sublattice and

their distribution may be influenced by the thermal

treatment. The Fe

3 þ

ions may be substituted by oth-

er trivalent magnetic (Mn

3 þ

,orCr

3 þ

) or nonmag-

netic (Ga

3 þ

,orAl

3 þ

) ions. Other possibilities are

represented by the Li-ferrite, Fe

3 þ

[Li

1 þ

0.5

Fe

3 þ

1.5

]O

4

,

and maghemite, g-Fe

2

O

3

-Fe

3 þ

[&

1/3

Fe

3 þ

5/3

]O

4

(where

& represents the cation vacancy).

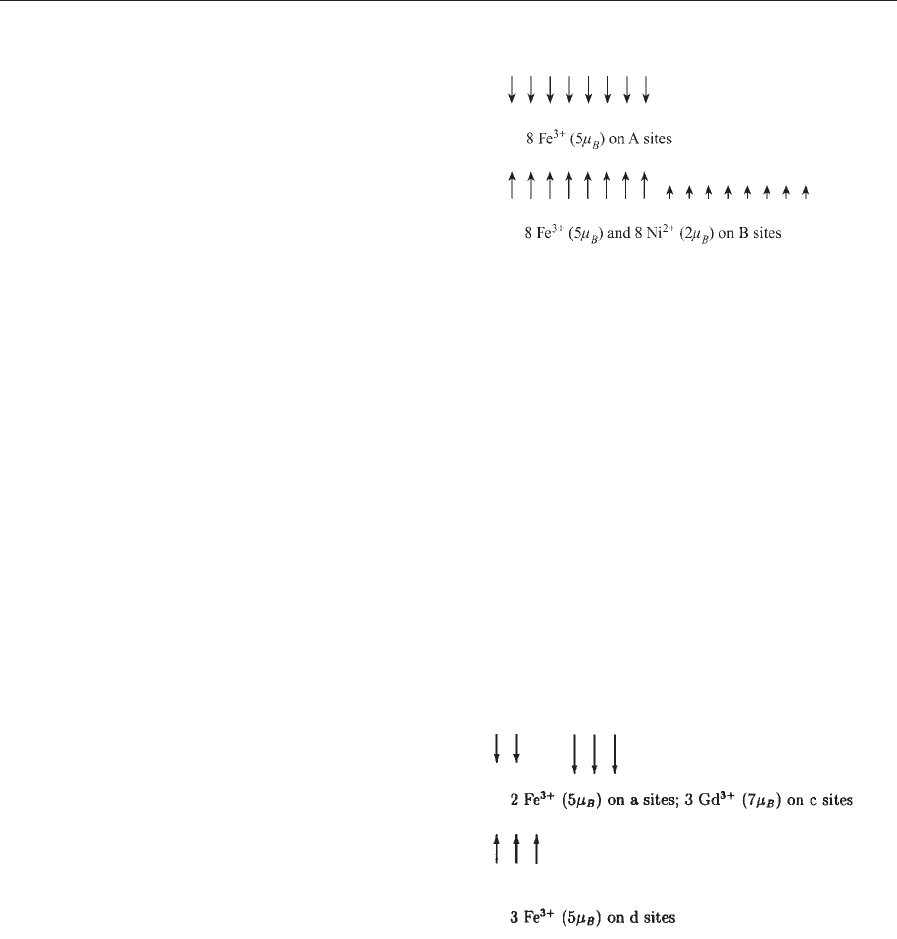

The dominating magnetic coupling in the spinel

ferrites is the antiferromagnetic A–B superexchange

interaction, leading to ferrimagnetic ordering. The

magnetic structure of nickel ferrite is thus:

2.2 Garnets

The ferrites with the garnet structure R

3

Fe

5

O

12

(R may be, for example, yttrium, trivalent rare-earth

ion, or bismuth) are cubic compounds with eight for-

mula units in the unit cell. The Fe

3 þ

ions occupy 16

tetrahedral (d) sites and 24 octahedral (a) sites. The

R

3 þ

ions fill 24 dodecahedral (c) sites. The ion dis-

tribution is thus {R

3 þ

3

}[Fe

3 þ

2

](Fe

3 þ

3

)O

2

12

.Ironcanbe

fully substituted by some other trivalent cations (e.g.,

Al

3 þ

,orGa

3 þ

), or partly by tetravalent (Si

4 þ

,or

Ge

4 þ

) or bivalent (Co

2 þ

,orMg

2 þ

) ions. If the sub-

stitute is not trivalent, the charge neutrality is main-

tained by the change of the iron valence. The bivalent

cations (e.g., Ca

2 þ

,Sr

2 þ

,orMn

2 þ

) may also enter

the c sublattice.

The dominating magnetic coupling in the garnet

ferrites is the antiferromagnetic a–d superexchange

interaction, leading to a ferrimagnetic ordering of

Fe(a) and Fe(d) spins. The spin of the rare-earth ions

on the c sublattice is antiparallel to the Fe(d) spin.

The magnetic structure of Gd

3

Fe

5

O

12

is:

Gd

3 þ

is an S-state ion with zero-orbital momen-

tum in the ground state. The exchange interactions in

Gd

3

Fe

5

O

12

are thus isotropic and the magnetic struc-

ture is collinear. In other rare-earth iron garnets the

magnetic moments of individual R

3 þ

ions are not

parallel to the magnetization forming so called um-

brella structure.

2.3 Hexagonal Ferrites

The most important hexagonal ferrites M

2

Fe

12

O

19

(M ¼Ba, Sr, or Pb) have the magnetoplumbite struc-

ture. The unit cell contains two formula units, and

1259

Transition Metal Oxides: Magnetism