Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of magnitude difference in commitments of time, per-

sonnel and funds to the two fields since the mid-1940s,

which are themselves measures of the relative com-

mercial importance of the two fields to date. Some

superconducting devices can be made in a single film

of material, the most common uses two films and the

most complex requires only three. Despite this, they

perform logic functions faster than the most advanced

semiconductor devices and at a level of power dissi-

pation which is orders of magnitude smaller (see Thin

Films, Multilayers and Devices, Superconducting).

Whether they will ever become more complex, or in-

deed need to do so, is an open question.

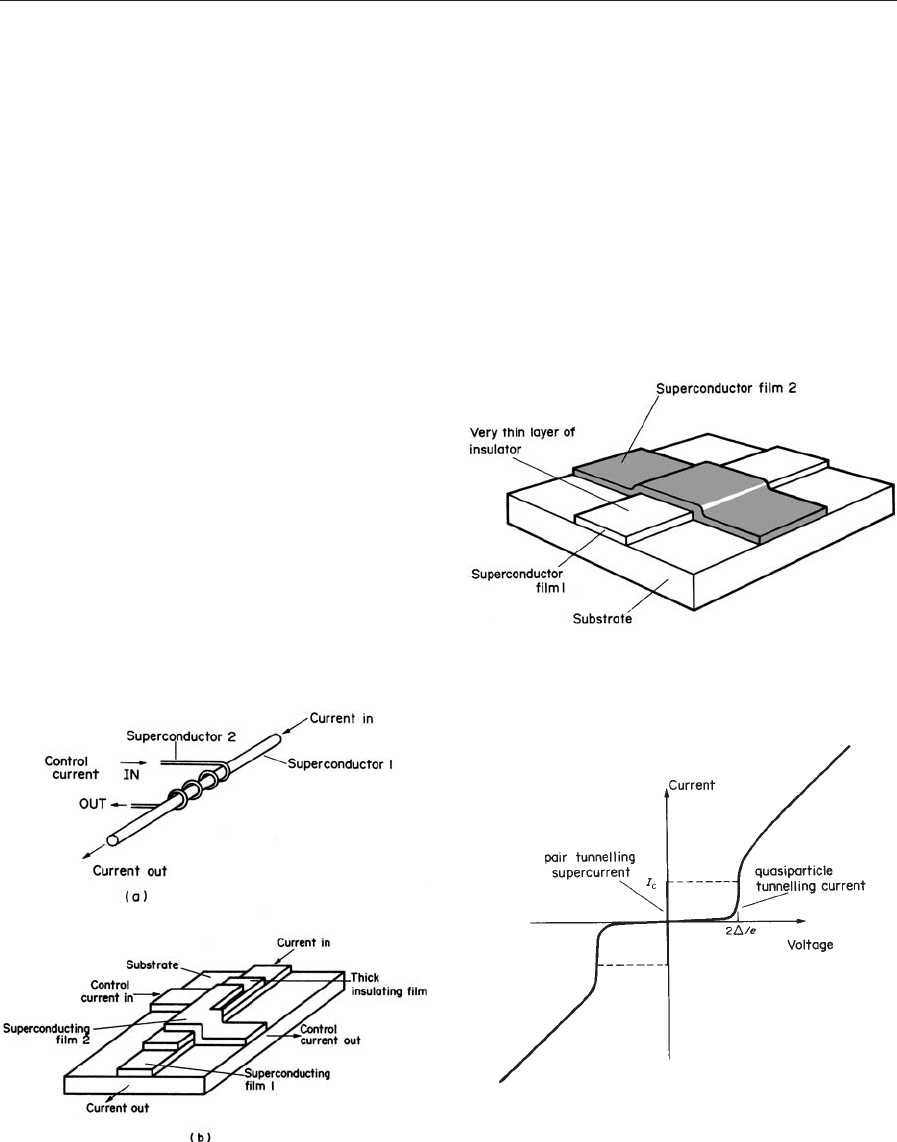

3.1 Tunnel Junctions and Weak Link Structures

Superconductors are affected strongly by magnetic

fields and only weakly by electric fields. This mag-

netic field sensitivity is the basis for many electronic

devices. In a superconducting film, or film adjacent to

a superconductor, a local region is produced where

the superconducting state can be controlled by ex-

ternal magnetic fields. The cryotron (Buck 1956),

which was the earliest superconducting electron de-

vice, used this principle. This device, which was in-

vented in 1954 and therefore predates the Josephson

effect, used two films (see Fig. 6) separated by an

insulator. A current through the control film created

a magnetic field which switched the second film from

its superconducting to its normal state. Recovery

from the normal state was not fast (by modern

standards). With the discovery of the Josephson

effect (see Josephson 1962) a much faster device be-

came possible. The Josephson junction (see Fig. 7)

consists of two superconducting films separated by a

thin insulator (o1.5 nm thick). This insulator allows

the tunnelling of pairs of electrons (the Josephson

current) and single electrons (the quasiparticle cur-

rent). These result in the tunnelling currents shown in

Fig. 8 as a function of the voltage across the insu-

lator. For an ideal junction there would be a discon-

tinuous jump at 2D/e and an exponentially small

subgap tunnelling current proportional to exp(D/

k

B

T) (Van Duzer and Turner 1981). In real systems

there is a smearing due to lifetime effects and non-

uniformity in the films. In addition there is invariably

a subgap leakage current. The sources of subgap

leakage vary from device to device and depend very

Figure 6

Cryotron types: (a) wire-wound type, (b) thin-film type.

Figure 7

Josephson junction (SIS tunnel junction).

Figure 8

I–V characteristic of Josephson junction for the case

where the two superconducting films have the same

energy-gap parameter D, the characteristic shows some

subgap leakage current.

1240

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Supercondu cting

much on the fabrication of the device. Leakage can

for instance arise from electron states within the tun-

nel barrier, or pinholes in the barrier itself. At low

temperatures for very-high-quality low-leakage bar-

riers, small subgap currents due to two-particle or

many-particle tunnelling can be observed (Kirk et al.

1991). If a small magnetic field is applied to the junc-

tion parallel to the films, the Josephson current is

reduced to zero when one quantum of magnetic flux

is in the area given by the width of the junction mul-

tiplied by the sum of the London penetration depths

of the two films (Rowell 1963). In practical devices,

this is about 0.1–1 mT. It is important to realize that,

in contrast to the cryotron, it is only the Josephson

current that is switched off by the magnetic field. The

two films comprising the junction remain entirely su-

perconducting at these low magnetic fields. In addi-

tion to control by magnetic field, the junction can

also be switched by increasing the current until the

maximum Josephson current is exceeded.

The Josephson tunnel junction has become the de-

vice of choice for LTS electronic, instrument and

sensor applications (Ruggiero and Rudman 1990). It

is fast and consumes little power. Its modern form,

made from Nb/Al–Al oxide–Nb, is described in detail

in SQUIDs; Biomedical Applications; SQUIDs: The

Instrument; Josephson Voltage Standard; Josephson:

Junctions: Low-T

c

Soon after the theoretical discovery and experi-

mental verification of the Josephson tunnel junction,

it was realized that Josephson effects could be ob-

served in many even simpler structures, which are

now collectively known as weak links (Anderson and

Dayem 1964). No tunnelling occurs in any of these

structures, they rely instead on creating a region of

weak coupling between two superconductors by var-

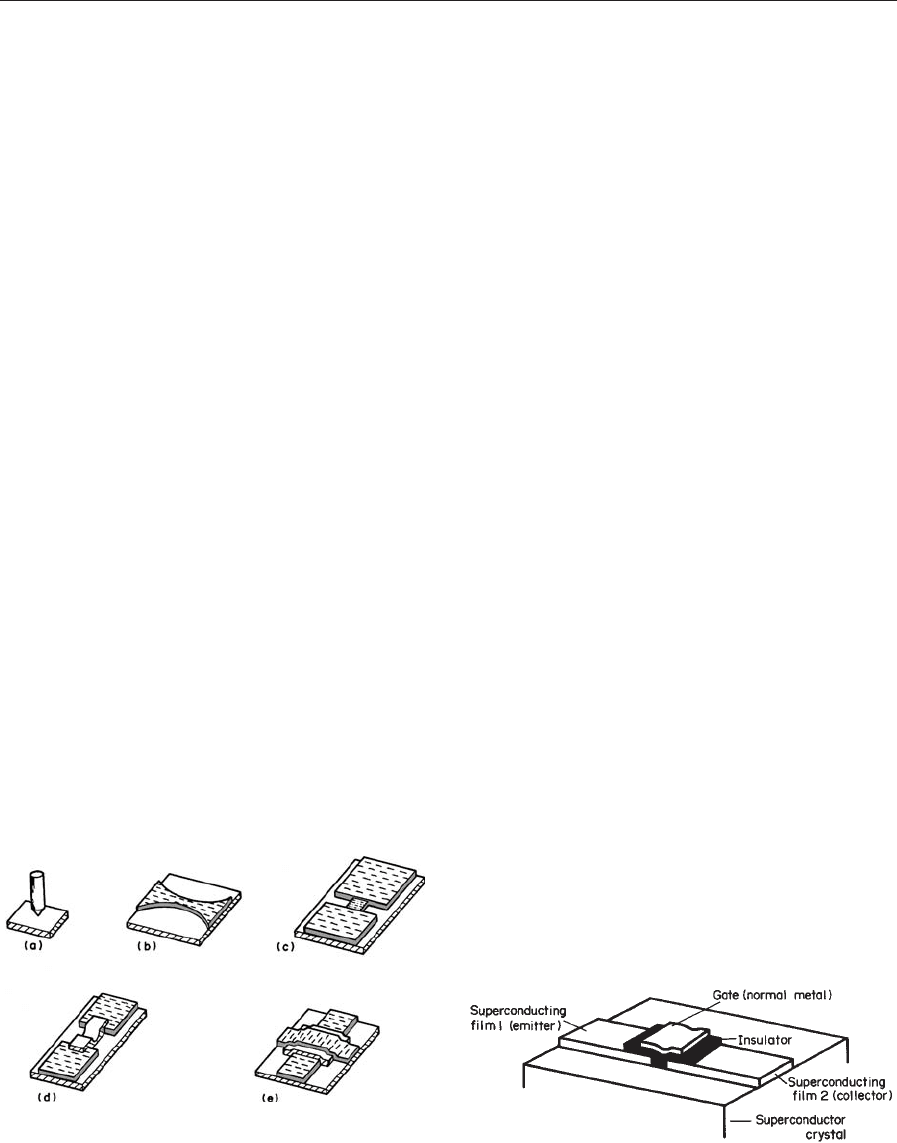

ious means other than an oxide layer. Some examples

are shown in Fig. 9. The simplest is a contact between

a pointed wire of one superconductor and a second

bulk superconductor (‘‘point contact’’). The thin-film

version is a small constriction defined in a film

(a ‘‘weak link’’, ‘‘bridge’’ or ‘‘microbridge’’). A ‘‘var-

iable thickness bridge’’ has the constriction both

thinner and narrower than the surroundings (banks).

The coupling region can also be made from a normal

metal, which is made weakly superconducting by the

proximity effect (SNS junction).

In all these Josephson weak link devices, the length

of the coupling region must be comparable to the

superconducting coherence length in that region. In

LTS materials and normal metals, standard film

growth and lithographic techniques can produce fea-

tures of the sizes required (generally t1 mm). In HTS

materials, this is obviously not possible.

Unlike the semiconducting transistor, supercon-

ducting devices do not have gain. At a fixed current

level, they simply switch between the zero voltage and

finite voltage states with application of magnetic field.

A few three-terminal devices have been investigated

that are more transistorlike in design, but not yet in

operation (Kleinsasser and Gallagher 1990). One ex-

ample is the superconducting FET (see Fig. 10), in

which two closely spaced superconducting contacts

induce a weak coupling region on the surface of a

semiconductor by the proximity effect. This super-

conducting channel is then switched on and off by

application of an electric field from the gate. To date,

large gate voltages are required to achieve switching

and the devices are not practical.

As of mid-1991, the device scene in HTS materials

is one of great activity and some uncertainty. All the

devices made in LTS materials are being investigated,

with varied levels of success. It is clear that the short

coherence lengths of the HTS materials creates a real

challenge in device design and processing. It does

seem likely that junctions of the weak link type will

emerge as more important than tunnel junctions, at

least in those HTS materials with T

c

477 K. The rea-

sons for this will be given later.

One HTS device has been created which has no

LTS counterpart. A control line modulates the flux

density in a weakened region of a second film (chan-

nel). It can be called a flux-flow cryotron (Martens

et al. 1991) in that the channel is switched from zero

resistance into its flux flow state, rather than into its

normal state. Its value in interface circuits has already

Figure 9

Josephson weak link structures: (a) point contact, (b)

constriction, (c) variable thickness bridge, (d) SNS

planar and (e) SNS sandwich.

Figure 10

Superconducting three-terminal device (FET type).

1241

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Superconducting

been demonstrated, in that its output voltage is quite

large (tens to hundreds of millivolts).

3.2 Device Processing: LTSs

The LTS weak link devices are relatively easy to

make with current lithographic techniques. Optical,

electron-beam and ion-beam patterning have all been

used to create the weak regions of dimensions 1 mmor

less in a variety of materials. The details will not be

discussed here.

Tunnel junctions exhibiting quasiparticle tunnel-

ling were first made in the late 1950s by the very

simple process of evaporating a strip of aluminum

film using a shadow mask, exposing it to the air for a

short time (B1 min), then evaporating a crossing

strip of lead to produce an Al–Al oxide–Pb tunnel

junction (Giaever 1960). The brief exposure to air

grows the required thickness of aluminum oxide

(B1.5 nm) which completely covers the aluminum

film even over relatively large areas of a few square

millimeters. It is important that there are no defects

or ‘‘pinholes’’ in the oxide, otherwise a metallic short

circuit occurs. This basic oxidation process has been

used for the vast majority of tunnel junctions made

on many different materials, and is used in the cur-

rent commercial process.

Other materials that have been used to make oxide

tunnel junctions include lead, tin, niobium, tantalum

and the alloys and A15 compounds of niobium. In

some cases the oxidation is not so easy as it is for

aluminum and heating in oxygen is required. Because

of its relatively high T

c

(7.2 K), lead and its alloys

received many years of study as the metallizations for

Josephson circuits. The problems that were encoun-

tered illustrate the difference between the research

mode of making a few successful junctions for scien-

tific study, and a manufacturing mode of rep-

roducibly making circuits that require many

thousands of junctions. The variation of critical cur-

rent density across these junctions must be small and

they must survive both shelf storage and many ther-

mal shocks as they are cycled from 300 K to 4.2 K

and back to 300 K. Because of the failure of lead, no

satisfactory metallization for Josephson circuits ex-

isted for 20 years (1963–1983). Niobium was an ob-

vious choice (T

c

¼9.2 K), but oxidation of niobium

itself produces a mixture of oxides with insulating,

semiconducting and even metallic properties. There is

probably also degradation of the niobium film sur-

face. This problem was finally solved by immediately

depositing a thin layer (o10 nm) of aluminum on top

of the niobium film in the same vacuum system, then

oxidizing the aluminum to form an aluminum oxide,

rather than niobium oxide, tunnel barrier (Geerk

et al. 1982).

Such ‘‘artificial’’ barriers have been used for a

number of other materials that do not readily oxidize

themselves. The best known example is MgO, which

is deposited as a thin layer on top of NbN to form

NbN–MgO–NbN tunnel junctions (Shoji et al. 1985).

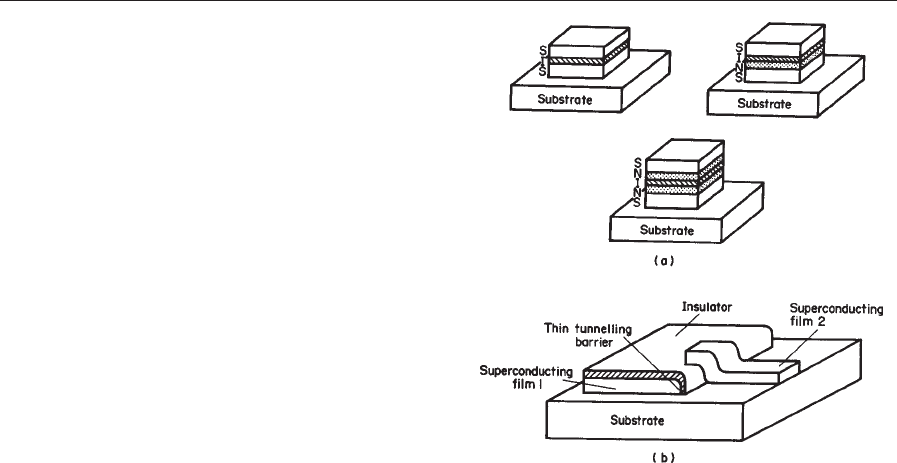

The different types of ‘‘sandwich’’ tunnel junctions

are shown in Fig. 11.

The sizes of sandwich junctions can be as small as

1 mm 1 mm using standard optical lithography and

submicrometer sizes using deep-UV sources. Another

way to make very small junctions is to oxidize the

edge of a film that has been cut by ion milling. Such

an ‘‘edge junction’’ is shown in Fig. 11. The small

capacitance of such structures makes them suitable

for high-frequency SIS detectors used in radio as-

tronomy studies.

3.3 Device Processing: HTSs

The new oxide materials with T

c

477 K are demand-

ing the invention of a new device technology. They

readily form tunnel junctions with counterelectrodes

of low-T

c

materials (Geerk et al. 1988), either because

their surfaces lose oxygen and become insulating, or

because the counterelectrode itself (e.g., lead) removes

the oxygen to form the insulator. However, such

junctions have no technological value. Obviously

there is no Josephson current until the temperature

is below T

c

of the counter electrode and, at least to

date (1991), none of them exhibits the I–V character-

istic of Fig. 8 with well-defined Josephson current

and energy gap. This comment applies to all the

Figure 11

(a) Three types of multilayer sandwich structure

Josephson junction, SIS, SNIS and SNINS; (b) edge-

type Josephson junction.

1242

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Supercondu cting

anisotropic oxides. Whether it is an intrinsic property

remains to be seen.

The isotropic oxides (e.g., BaPbBi oxide, BaKBi

oxide) are strikingly different. A ‘‘classical’’ I–V

characteristic of the type shown in Fig. 8 has been

observed by simply touching a BKBO single crystal

to a BKBO film and work is underway to produce

similar results in a thin-film sandwich structure. At

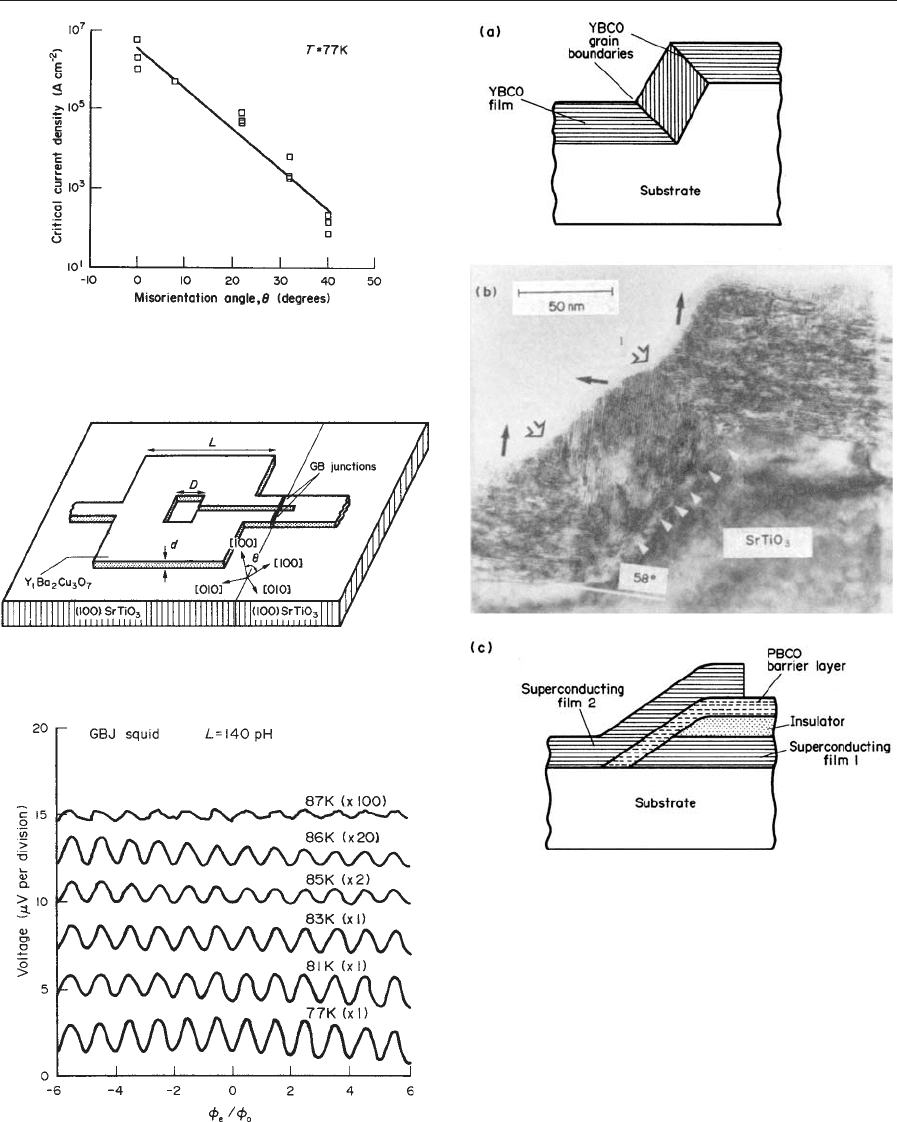

Figure 12

Variation of critical current density with misorientation

angle for grain boundaries in YBCO films on yttria-

stabilized zirconia (YSZ) substrates.

Figure 13

Bicrystal SQUID structure with grain boundary

junctions.

Figure 14

Field modulation of bicrystal SQUID illustrated in Fig.

13 for temperatures between 77 K and 87 K.

Figure 15

(a) Schematic of steep step junction with two grain

boundaries, (b) electron micrograph of 581 step junction

in a YBCO film on SrTiO

3

(after Jia et al. 1991) and

(c) schematic of a shallow step junction with a normal

PrBCO layer.

1243

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Superconducting

present, the maximum T

c

in an isotropic oxide su-

perconductor is about 30 K. However, this would al-

low a Josephson technology similar to that developed

for niobium to be used at 12–15 K, well within the

range of closed cycle refrigerators of reasonable cost.

Thus, these isotropic oxides might become important

metallizations for electronics applications.

In the absence of any useful tunnel junctions in

HTS materials, the weak link devices are of more

importance than they were in the LTS field (although

it is true that most of the SQUID-based LTS mag-

netometers that have been sold have in fact used such

weak links rather than tunnel junctions). A great va-

riety of device structures are being investigated at

present (mid-1991). Many of them make SQUIDs

operating at 77 K. Whether any of them will become

the basis of a genuine circuit technology remains to

be seen. They include SNS devices where the N layer

can be silver (or silver–gold alloy). In one geometry

the silver covers a break in the HTS film induced by a

step in the substrate. Other N layers are semicon-

ducting and ‘‘metallic’’ oxides, in various geometries

(Simon 1991). The possible presence of a proximity

effect in such oxides is an interesting issue.

To define a weak link constriction, or region of

reduced J

c

and T

c

, of a size comparable to the very

short coherence lengths, is difficult in HTS materials.

However, electron-beam writing and focused ion-

beam milling have been used with some success, and

the use of patterning by a scanning tunnelling mi-

croscope has been proposed. In one structure nature

itself seems to provide a structure of the correct di-

mensions, namely a boundary between two grains in

the film. The cleanest examples of such devices are

grain boundary junctions grown on substrates that

were cut and deliberately misaligned in the plane by

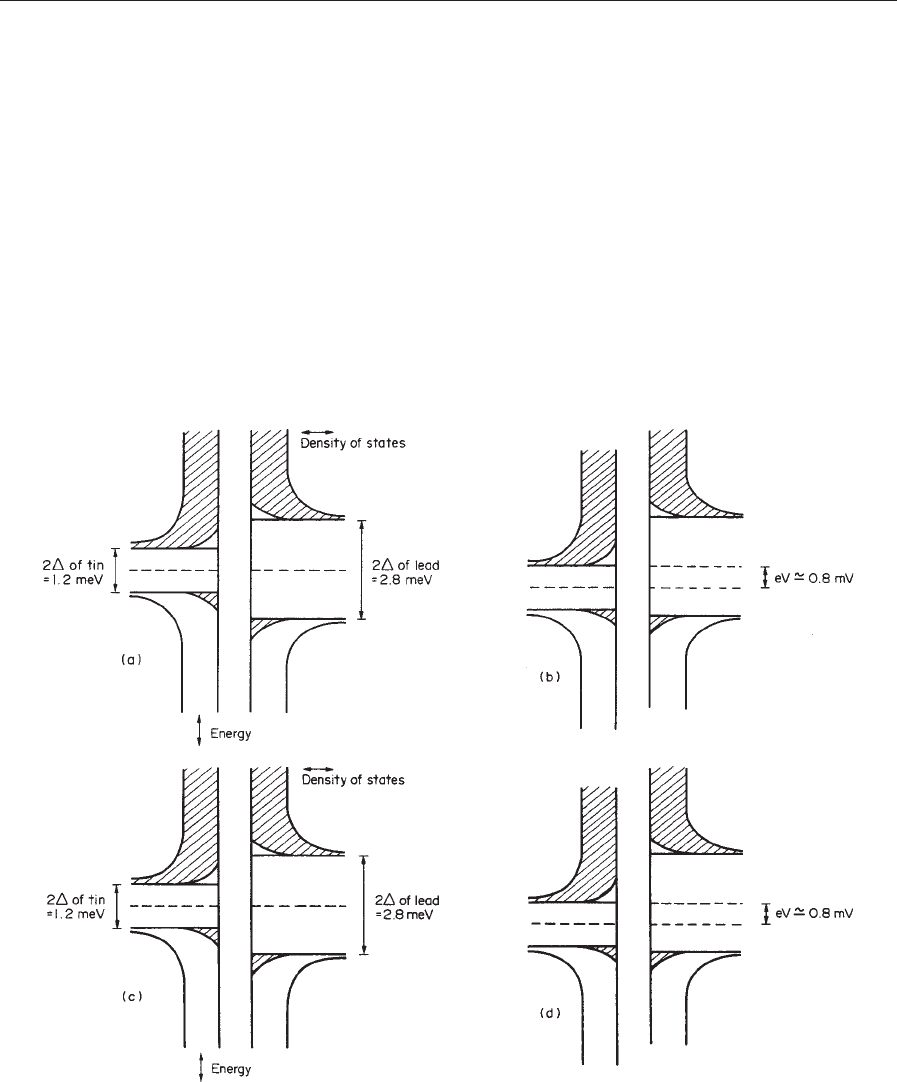

Figure 16

The density of filled and empty quasiparticle states for lead and tin superconducting layers on each side of a tunnel

barrier. An applied voltage V leads to a relative displacement of the density of state diagrams, the voltage

corresponding to the gap 2D is 2D/e: (a) zero applied voltage; (b) eV ¼D

Pb

D

Sn

C0.8 mV; (c)

D

Pb

D

Sn

oeVoD

Pb

þD

Sn

, eVC1.4 mV; and (d) eV ¼D

Pb

þD

Sn

C2.0 mV.

1244

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Supercondu cting

various tilt angles (Gross et al. 1990a). The film,

growing epitaxially, replicates the orientation of the

substrate. On yttria-stabilized zirconia substrates, the

critical current drops exponentially with angle, by

four orders of magnitude as the angle is increased

from 0 to 401 (see Fig. 12) (Ivanov et al. 1991).

SQUIDs of YBCO showing modulation with mag-

netic field up to 87 K have been produced with such

grain boundary junctions (Gross et al. 1990b). (See

Fig. 13, which shows the structure, Fig. 14 demon-

strating the modulation and also the article Josephson

Junctions: High-T

c

.)

A step geometry has also been used to form weak

link HTS junctions (see Fig. 15). If the angle of the step

is steep (y4451) single or multiple grain boundaries

form at the discontinuity in the substrate surface

(Fig. 15a,b). For shallow junctions (yo351)theepitaxy

is preserved at the step and an SNS junction can be

formed by depositing a heteroepitaxial layer of normal

PrBCO (Fig. 15c) (Gao et al. 1991). In this junction

films are grown with the c axis normal to the substrate

so that the tunnelling current is in the ab plane, the

direction with longest coherence length.

An alternative process called biepitaxy creates a

grain boundary in the film by control of the in-plane

epitaxy using seed and buffer layers (Char et al.

1991a), rather than by changing the substrate orien-

tation. This process could allow complex circuits of

grain boundary junctions to be demonstrated, as the

junction can be located at any point on a single-crys-

tal substrate. The first integrated SQUID magneto-

meter fabricated on one chip used such biepitaxial

grain boundary junctions (Char et al. 1991b).

3.4 Properties of Devices

The ideal BCS current–voltage characteristic of LTS

tunnel junctions can be readily understood by the use

of semiconductorlike diagrams in which the filled and

empty quasiparticle states are shown at an energy 2D

apart and have (E

2

D

2

)

1/2

energy dependencies of the

density of states (see Fig. 16). The superconducting

pairs are shown at the Fermi level, the midpoint of

the gap. The effect of an applied voltage V is simply

to slide the Fermi levels and thus the whole gap

structures relative to each other by a distance eV. The

effect of temperature is included by a thermal distri-

bution over only the quasiparticle states.

The most interesting case is that of two supercon-

ductors with different energy gaps, say tin and lead to

be specific. The T

c

values are 3.7 K and 7.2 K, and the

energy-gap parameters D ¼0.6 meV and 1.4 meV, re-

spectively or 2D ¼1.2 meV and 2.8 meV. The density

of states diagrams are then as shown in Fig. 16a at

zero voltage and a temperature significantly below

the T

c

of tin. As the voltage is increased, a maximum

in current occurs at eV ¼D

Pb

D

Sn

(Fig. 16b), but the

current then decreases for larger voltages. This is

because the current is the integral over the filled and

empty states that are aligned with each other, which

is smaller in Fig. 16c than in Fig. 16b. A sudden

increase in current occurs for eV ¼D

Pb

þD

Sn

in

Fig. 16d. In theory, this should be a discontinuous

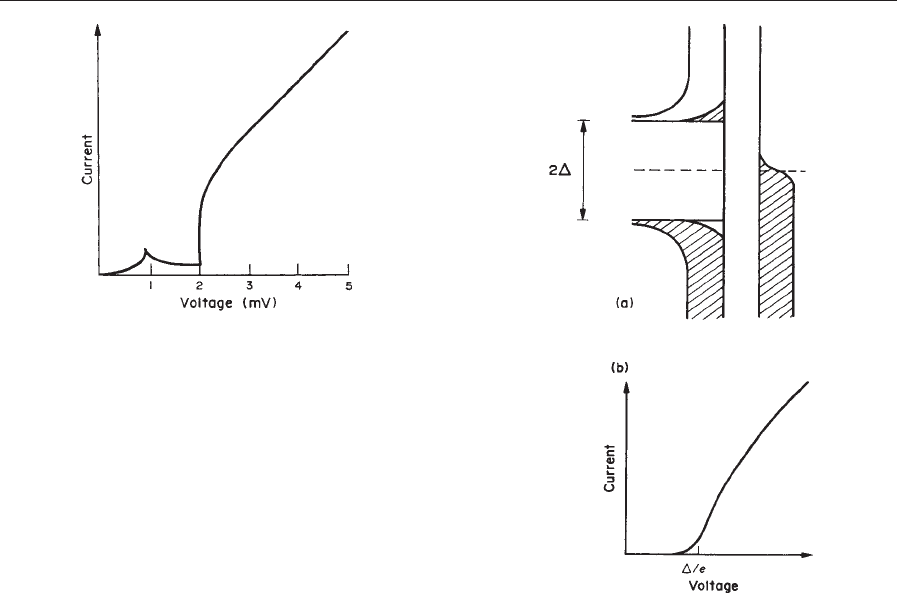

Figure 17

The current–voltage characteristic for the tunnelling of

quasiparticles in an Sn–I–Pb junction.

Figure 18

SIN tunnel junction: (a) density of filled and empty

states at zero applied voltage, and (b) current–voltage

characteristic at finite temperature.

1245

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Superconducting

jump in current at any temperature, but in practice it

has a slight width due to lifetime effects and nonuni-

formities in the films.

At high voltages, the current–voltage characteristic

approaches that of the normal state. The quasipar-

ticle branch of the characteristic is shown in Fig. 17;

the complete characteristic, including the Josephson

current of pairs flowing at V ¼0 exhibits the main

features of Fig. 8. Another interesting case is the S–I–

N junction, where N is a normal metal, for which the

density of states diagram and I–V characteristic are

shown in Fig. 18. The reader should be able to rec-

reate the I–V characteristics by following the process

of sliding the density of states as described.

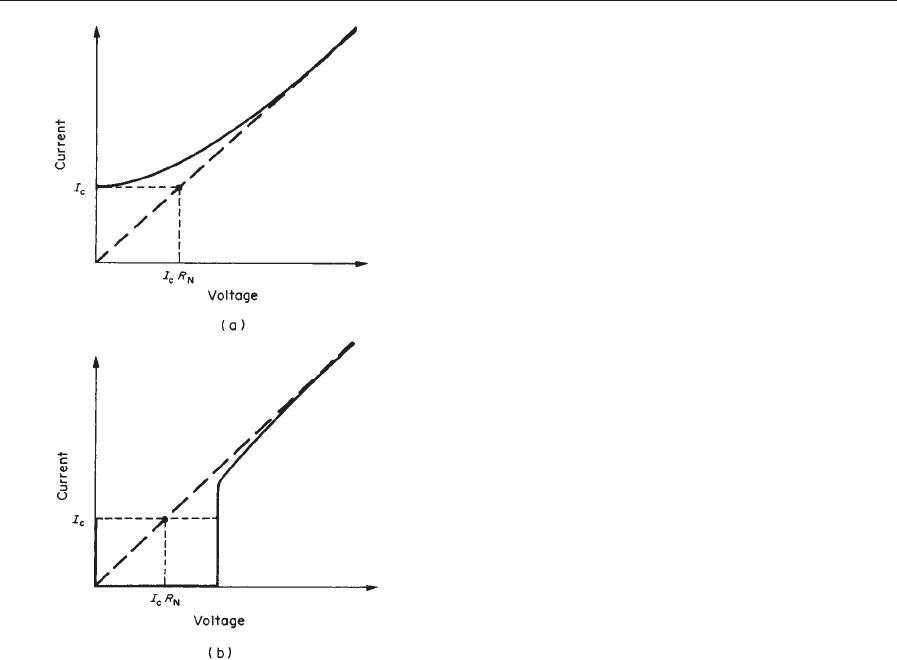

In weak link devices, as there is no tunnelling,

there is no signature of the energy gap in the I–V

characteristic. In many such devices, the I–V charac-

teristic resembles that for a tunnel junction with

a low-resistance shunt across it, the resistively

and capacitatively shunted junction (RCSJ) (see

Electrodynamics of Superconductors: Weakly Coupled ).

The I–V characteristic then appears as in Fig. 19.

An important ‘‘figure of merit’’ for both LTS and

HTS devices of both tunnelling and weak link types is

the I

C

R

N

product, which is the voltage defined in Fig.

19. It is related to the signal voltage that is available

in a SQUID or circuit. Obviously it should be large

(millivolts). It can be p3 mV in niobium tunnel junc-

tions, but in many HTS devices, especially the SNS

type, it is very small (e.g., tens of microvolts). This

makes such structures less interesting for practical

applications.

A second figure of merit, used for tunnel junctions,

is a measure of the subgap leakage current that flows

for voltages less than the energy gap compared with

the current that would flow at the same voltage in the

normal state. This can be expressed as the ratio R

S

/R

N

calculated at some defined voltage (e.g., 2 mV for nio-

bium devices), or as a voltage V

m

defined as R

S

times

the critical current I

c

. In an ideal junction, this current

is only due to quasiparticles that are thermally excited

above the gap. Hence, at temperatures small com-

pared with T

c

, it should be very small. For example,

for Pb–I–Pb junctions at 1 K values for R

S

/R

N

of 10

5

have been observed. For Nb–I–Nb at 4.2 K most of

the subgap current is thermally excited and the ratio is

about 20–25. Values lower than this indicate a poor

quality junction with some non-tunnelling leakage

paths for the excess current. The most obvious pos-

sibility is a small pinhole in the tunnel barrier.

4. Concluding Remarks

The discovery of the HTS oxides raises interesting

questions of how LTS and HTS junction technologies

will be used, assuming that the latter can be devel-

oped. There are strong signs that this will happen. In

some areas of application, it seems likely that HTS

and LTS technologies will compete with each other,

as they do with silicon and GaAs in some cases.

In one example, the most sensitive SQUIDs for

measuring magnetic signals from the brain might well

remain at 4.2 K, whereas for other measurements,

where portability of the equipment is needed (e.g.,

nondestructive evaluation of pipes) 77 K operation

will be favored.

The majority of the digital circuits that have been

built with niobium tunnel junctions employ ‘‘voltage

state logic,’’ in which the two states of the junction

are at zero voltage and about 2.9 mV. Power dissi-

pation is the product of the current and this voltage

for the time that the junction remains switched. If

HTS junctions of the same type could be made, the

advantages of the low power dissipation of super-

conducting technology would be partly lost. The

voltage (gap) would be ten times larger, and the cur-

rent also ten times larger (to scale with the operating

temperature); hence, the power would be 100 times

larger.

Figure 19

(a) The current–voltage characteristic for a weak link

with a resistively shunted junction RSJ type transition,

the I

C

R

N

product for the weak link is indicated; and (b)

I

C

R

N

product for Josephson tunnel junction.

1246

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Supercondu cting

However, there is a class of superconducting cir-

cuits, known as QFP (quantum flux parametron) or

SFQ (single flux quantum) circuits, that avoid this

problem and, hence, regain the advantage of the very

low power dissipation of Josephson technology, even

at temperatures up to 77 K. The basic circuit element

is the SQUID and power is dissipated only when a

quantum of flux (which is the bit of information in

QFP) moves in or out of the SQUID loop. The mo-

mentary voltage pulse is the bit of information in

SFQ circuits. Such circuits do not need Josephson

junctions of the type shown in Fig. 8; in fact they can

use weak link devices. Thus, they appear to be the

most likely candidates for initial demonstrations of

HTS high-speed electronics.

Another divergence between LTS and HTS that is

already becoming apparent is the extensive use of fully

epitaxial multilayer devices in HTS. In this materials

aspect, HTS begins to resemble III–V semiconductor

technology much more than it does conventional su-

perconductor (niobium) technology. As an example,

an integrated HTS SQUID magnetometer has been

fabricated which utilized 15 epitaxial oxide layers of

superconductors and insulators, plus a final silver

contact layer (see Char et al. 1991a). Indeed, the field

of superconducting thin films, multilayers and devices

is changing and progressing rapidly.

See also: Films and Multilayers: Conventional

Superconducting; Metrology: Superconducting

Cryogenic Current Comparators; Superconducting

Machines: Energy Distribution Components; Super-

conduction Radiation Sensors; Superconducting

Thin Films: Materials, Preparation and Properties;

Superconducting Wires and Cables: Materials and

Processing

Bibliography

Anderson P W, Dayem A H 1964 Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 195

Banerjee I, Yang Q S, Falco C M, Schuller I K 1983 Aniso-

tropic critical fields in superconducting superlattices. Phys.

Rev. B 28, 5037–40

Braginski A I, Talvacchio J 1990. In: Ruggiero S T, Rudman D

A (eds.) 1990 Superconducting Devices. Academic Press, San

Diego, CA, Chap. 8, p. 273

Brandt N B, Ginzburg N I 1960 Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 39, 1554

Buck D A 1956 Proc. IRE 44, 482

Buckel W, Gey W 1963 Z. Phys. 176, 336

Char K, Colclough M S, Garrison S M, Newman N,

Zaharchuk G 1991a Biepitaxial grain-boundary junctions in

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

. Appl. Phys. Lett. 59 , 733–5

Char K, Colclough M S, Lee L P, Zaharchuk G 1991b Exten-

sion of the biepitaxial Josephson junction process to various

substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 59, 2177–9

Eom C B, Sun J Z, Yamamoto K, Marshall A F, Luther K E,

Geballe T H, Cadermann S S 1989 In situ grown

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

thin films from single-target magnetron sput-

tering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 55 (6), 595–7

Gao J, Aarnink W A M, Gerritsma G J, Veldhuis D, Rogalla H

1991 Preparation and properties of all high T

c

SNS-type edge

dc SQUIDS. IEEE Trans. Magn. 27, 3062–5

Geerk J, Gurvitch M, McWhan D B, Rowell J M 1982 Physica

109, 1775

Geerk J, Xi X X, Linker G 1988 Electron tunnelling into thin

films of Y

1

Ba

2

Cu

3

O

7

. Z. Phys. B 73, 329–36

Giaever I 1960 Phys. Rev. Lett. 5, 147

Greene L H, Bagley B G 1990 In: Ginsberg D M (ed.) 1990

Physical Properties of High Temperature Superconductors II.

World Scientific, Singapore, p. 509

Gross R, Chaudhari P, Dimos D, Gupta A, Koren G 1990a

Thermally activated phase slippage in higher T

c

grain bound-

ary Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 228–31

Gross R, Chaudhari P, Kawasaki M, Ketchen M B, Gupta A

1990 Low noise YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

grain boundary junction dc

SQUIDS. Appl. Phys. Lett. 57, 727–9

Hammond R H 1975 IEEE Trans. Magn. 11, 201

Inam A, Hegde M S, Wu X D, Venkatesan T, England P, Miceli

P F, Chase E W, Chang C C, Tarascon J M, Wachtman J B

1988 As-deposited High-T

c

and J

c

superconducting thin films

made at low temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 53, 908–9

Ivanov Z G, Nilsson P A, Winkler D, Brorsson G, Claeson T

1991 Proc. SQUID 1991 (in press)

Jia C L, Kabius B, Urban K, Herrman K, Cui G J, Schubert J,

Zander W, Braginski A I, Heiden C 1991 Microstructure of

epitaxial YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

films on step edge SrTiO

3

substrates.

Physica C 175, 545–54

Josephson B D 1962 Phys. Lett. 1, 251

Karkut M G, Matijaservic V, Antognazza L, Triscone J-M,

Missert N, Beasley M R, Fischer Ø 1988 Anomalous upper

critical fields of superconducting multilayers—verification of

the Takahashi–Tachiki effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1751–4

Kirk E C G, Blamire M G, Somekh R E, Evetts J E, Van

Vechten D, Lovellette M N 1991 Ultra-high quality Nb/

AlO

x

/Nb tunnel junctions with epitaxial base layers. IEEE

Trans. Magn. 27, 3137–40

Kleinsasser A W, Gallagher W J 1990 In: Ruggiero S T, Rud-

man D A (eds.) 1990 Superconducting Devices. Academic

Press, San Diego, CA, Chap. 9, p. 325

Li Y Q, Zhao J, Chern C S, Huang W, Kulesha G A, Lu P,

Gallois B, Norris P, Kear B, Cosandey F 1991 High critical

current densities in YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

thin films formed by met-

allorganic chemical vapor deposition at 730 1C. Appl. Phys.

Lett. 58, 648–50

Lowndes D H, Norton D P, Budai J D 1990 Superconductivity

in nonsymmetric epitaxial YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

/PrBa

3

Cu

3

O

7x

su-

perlattices—the superconducting behavior of Cu–O bilayers.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 1160–3

Martens J S, Ginley D S, Beyer J B, Nordman J E, Hohen-

warter G K G 1991 A Josephson junction to FET high-speed

line driver made of T1CaBaCuO. IEEE Trans. Magn. 27,

3284–8

Rowell J M 1963 Phys. Rev. Lett. 11, 200

Ruggiero S T, Barbee T W, Beasley M R 1980 Phys. Rev. Lett.

45, 1299

Ruggiero S T, Barbee T W, Beasley M R 1982 Phys. Rev. B 26,

4894

Ruggiero S T, Rudman D A (eds.) 1990 Superconducting

Devices. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

Shinjo T, Takeda T 1987 Metallic Superlattices. Elsevier,

Amsterdam

Shoji A, Aoyagi M, Kosaka S, Shinokik F, Hayakawa H 1985

Niobium nitride Josephson tunnel junctions with magnesium

oxide barriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 46, 1098–100

1247

Thin Films, Multilayers and Devices, Superconducting

Simon R 1991 High-T

c

thin films and electronic devices. Phys.

Today 44 (6), 64–70

Somekh R E, Shih W C, Dyrbye K, Huang K H, Baxter C S

1989 The Sputter Deposition of Metal Multilayers, X-Ray

Instrumentation, SPIE Vol. 1140. Society of Photo-Optical

Instrumentation Engineers, Bellingham, WA, pp. 453–63

Taber R C 1990 A parallel plate resonator technique for mi-

crowave loss measurements on superconductors. Rev. Sci.

Instrum. 61, 2200–6

Takahashi S, Tachiki M 1986 Theory of the upper critical

field of superconducting superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 33, 4620–

31

Van Duzer T, Turner C W 1981 Principles of Superconductive

Devices and Circuits. Elsevier, Amsterdam

J. M. Rowell

Conductus Inc., Sunnyvale, California, USA

Thin Films: Domain Formation

Soft magnetic films and nanostructures are of interest

for applications as sensors and storage material.

Most desirable are single-domain structures that

switch their magnetization at a certain field by fast

coherent rotation. These ideal films, so far, have not

been produced; the films tend to break up into do-

mains along the magnetization loop. The formation

of domains in soft magnetic films and nanostructures

has to be understood for the discussion of the mag-

netic properties of the films and nanostructures and

how to select them for applications.

A desirable ideal state of the magnetization in thin

ferromagnetic films is the single-domain state in

which at remanence the magnetization is directed

along an easy axis. Application of an external field

should cause coherent rotation of the magnetization

towards the applied field. Magnetization reversal is

expected by spontaneous switching at a critical field.

Nature does not follow these idealized assumptions.

For discussing the static equilibrium state of the

magnetization in a real sample one has to consider

the integral minimum of all magnetic energies: the

Zeeman energy e

H

¼

~

H

~

M of the sample in an ap-

plied field; the crystalline anisotropy energy e

K

; the

uniaxial anisotropy energy e

K

u

; the magnetostrictive

anisotropy energy e

s

; the exchange anisotropy e

ex

; the

external demagnetizing self-energy e

dext

¼(1/2)

~

H

dext

~

M, where

~

H

dext

is the demagnetizing field from

magnetic poles at the film boundaries; the intrinsic

demagnetizing self-energy e

dint

¼(1/2)

~

H

dint

~

M,

where

~

H

dint

is the demagnetizing field resulting from

intrinsic magnetization divergencies; the surface an-

isotropy s

s

; and the wall energy s

w

(Kittel 1949,

Craik and Tebble 1965).

All of these energy densities have to be integrated

over the volume of the film. Their minimum gives the

stable state of magnetization distribution in the

film. This problem is treated in the field of micro-

magnetism.

Experimental observation of domains gives a first

indication of how to approximate this difficult prob-

lem, which is then reduced to the domain theory,

in which the domains are separated by walls and

homogeneous magnetization is assumed within do-

mains (Kittel 1949).

The methods of domain observation have in-

creased in sensitivity and resolution over the years.

They include the Bitter pattern, magneto-optical Far-

aday and Kerr rotation, Lorentz microscopy, spin

polarized photoemission of electrons, and x-ray di-

chroism (Hubert and Scha

¨

fer 1998). These methods

will not be discussed in this article.

Why is the single-domain state of a film not a state

of lowest energy? Why does the film break up into

domains?

(i) The film size is finite. Magnetic poles at the

boundaries cannot be avoided in the single-domain

state, leading to strong magnetic self-energy. The to-

tal magnetic energy is decreased when this self-energy

is decreased by domain formation. The additional

increase in energy owing to domain wall energy is

smaller than the decrease of the self-energy.

(ii) Nonideal films, for instance polycrystalline

films, show fluctuation of the direction of the local

magnetization around the mean direction, the so-

called magnetization ripple (Hoffmann 1968). In

some cases this ripple is responsible for nucleation

of domains. The ripple prevents a coherent switching

of single domains.

Domain formation in thin films is many and var-

ied. It can be explained in the best way by discussing

soft magnetic thin films with uniaxial magnetic an-

isotropy, which are applied as magnetic sensors. The

uniaxial anisotropy results from film deposition in the

presence of a magnetic field parallel to the film plane

or from field annealing below the Curie temperature

of the deposited film. In both cases the direction of

the applied field introduces an easy axis of the mag-

netization parallel to the applied field. Permalloy

(Ni

91

Fe

19

) is the typical material used for soft mag-

netic uniaxial films.

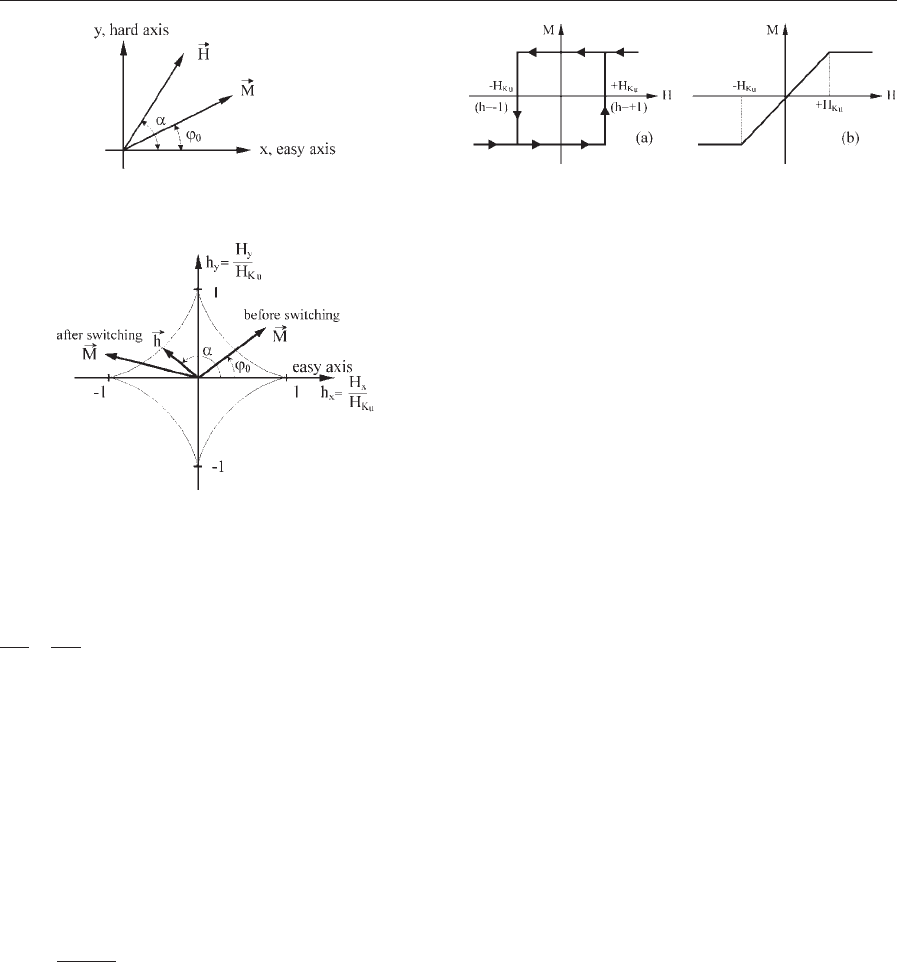

1. The Single-domain Theory of Stoner and

Wohlfarth

The magnetization reversal of ideal uniaxial films is

theoretically described by the Stoner–Wohlfarth sin-

gle-domain theory (Stoner and Wohlfarth 1948,

Cohen 1969, Prutton 1964), in which an ideal uniax-

ial film with homogeneous in-plane magnetization is

assumed.

The in-plane magnetization loops with applied field

in the easy or hard direction are calculated from

the minimum of the Zeeman energy,

~

M

~

H, and the

1248

Thin Films: Domain Formation

uniaxial anisotropy energy, K

u

sin

2

j

0

(Fig. 1), lead-

ing to

@e

@j

0

¼

@

@j

0

½HM cosða j

0

ÞþK

u

sin

2

j

0

¼HM sinða j

0

Þþ2K

u

sinj

0

cos j

0

¼ 0 ð1Þ

for the equilibrium state.

Introducing the anisotropy field H

K

u

¼2K

u

/M,

which is characteristic for uniaxial films, the equilib-

rium state is given by

h sinða2j

0

Þþcos j

0

sin j

0

¼ 0 ð2Þ

The field h ¼H/H

K

u

¼HM/2K

u

is the applied field

in units of H

K

u

, which will be used in the following

discussions.

The effective field, h(a), in units of H

K

u

, is given by

1

2K

u

@

2

e

@j

2

0

¼ hðaÞ¼h cosða j

0

Þþcos2j

0

ð3Þ

which determines the stability of the magnetization.

Stable states require h(a)40; instability, i.e. switch-

ing, occurs for h(a) ¼0 (Hoffmann 1966, 1968).

The equation

hðaÞ¼h cosða j

0

Þþcos2j

0

¼ 0 ð3aÞ

describes the well-known Stoner–Wohlfarth astroid

(Fig. 2) (Stoner and Wohlfarth 1948, Cohen 1969,

Prutton 1964).

On applying a field

~

H at an angle a to the easy axis,

for which the magnetization at H ¼0 was originally

saturated, the magnetization is coherently rotated by

an angle j

0

from the easy axis. As soon as the

applied field

~

H crosses the astroid, the magnetization

switches spontaneously by coherent rotation into a

new stable state (Fig. 2).

In the special case of applying the field along the

easy axis, the magnetization remains stable in the

original state, until at H ¼H

K

u

it switches spontane-

ously to the antiparallel direction by coherent rotation

(Fig. 3(a)). These two stable states, switched at H

K

u

,

make uniaxial films desirable for magnetic storage.

Unfortunately, in reality, coherent switching along the

easy axis is not observed. Instead, the magnetization of

the films breaks up into domains, and magnetization

reversal is completed by domain wall motion with co-

ercive force 7H

c

7o7H

K

u

7 (see Figs. 10(a) and (b)).

In the special case of applying the field along the

hard axis, the magnetization rotates continuously

from the easy axis against the direction of the applied

field, until at H ¼H

K

u

the magnetization is saturated

in this direction. The expected magnetization loop is

given in Fig. 3(b). In this way the uniaxial film is used

as a field sensor (see also Coercivity Mechanisms).

2. Magnetization Ripple

In discussing magnetization reversal in real polycrys-

talline films or in single-crystalline films, including

defects, one has to include inhomogeneous local an-

isotropies, such as crystalline anisotropy and magne-

tostriction of the crystallites. These local anisotropies

lead to deviations, j, of the local direction of the

magnetization from the mean direction j

0

. The mag-

netization is no longer homogeneous over the entire

film. The fluctuations are coupled in elliptical areas

over many crystallites. The major axis of the coupling

ellipse is always directed perpendicular to the mean

magnetization and is determined by dipolar coupling.

The minor axis, parallel to the mean magnetization, is

determined by the exchange length.

The fluctuation j can be seen in images obtained

by Lorentz microscopy (Fig. 4). This ‘‘magnetization

ripple’’ (Hoffmann 1966, 1968, Cohen 1969) dominates

Figure 2

Stoner–Wohlfarth astroid.

Figure 3

Magnetization loops of uniaxial films: (a) easy axis;

(b) hard axis.

Figure 1

System of coordinates and angles.

1249

Thin Film s: Domain Formation