Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Engdahl G (ed.) 1999 Handbook of Giant Magnetostrictive Ma-

terials: Physics and Device Applications. Academic Press,

London

Fujita A, Fukamichi K 1999 Giant volume magnetostriction

due to the itinerant electron metamagnetic transition in

La(Fe–Si)

13

compounds. IEEE Trans Magn MAG-35,

3796–801

Hubert A, Scha

¨

fer R 1998 Magnetic Domains. Springer, Berlin

James R D, Kinderlehrer D 1994 Theory of magnetostriction

with application to Terfenol-D. J. Appl. Phys. 76, 7012–4

Ne

´

el L 1937 E

´

tudes sur le moment et le champ mole

´

culaire des

ferromagne

´

tiques. Ann. Phys. 8, 237–308

Quandt E, Ludwig A 1999 Giant magnetostrictive multilayers.

J. Appl. Phys. 85, 6232–7

Sablik M, Jiles D C 1993 Coupled magnetoelastic theory of

magnetic and magnetostrictive hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Magn

MAG-29, 2113–23

Sander D, Enders A, Kirschner J 1999 Stress and magnetic

properties of surfaces and ultrathin films. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 200, 439–55

Tremolet de Lacheisserie E du, 1993 Theory and Applications of

Magnetoelasticity. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Wassermann E F 1990 Invar: moment-volume instabilities in

transition metals and alloys. In: Buschow K H J, Wohlfarth

E P (eds.) Ferromagnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amster-

dam, Vol. 5, Chap. 3, pp. 237–322

Wu R Q, Chen L J, Shick A, Freeman A J 1998 First principles

determination of magnetocrystalline anisotropy and magne-

tostriction in bulk and thin film transition metals. J. Magn.

Magn. Mater 177–81, 1216–9

W. Andrae and R. Mattheis

IPHT Jena, Germany

D. Berkov

Innovent, Jena, Germany

Superconducting Machines: Energy

Distribution Components

Most of the potential applications of superconduc-

tivity in power systems benefit from zero resistance

and high critical current densities in the supercon-

ducting state thus reducing losses and size of com-

ponents, for example the generator, transformer,

cable (see Superconducting Wires and Cables: Low-

field Applications), SMES (superconducting magnetic

energy storage) and motor. But, there is also a po-

tential application which utilizes the transition from

the superconducting to the normal-conducting state

in order to limit fault currents. The device is usually

referred to as a superconducting fault current limiter

(SCFCL).

1. Superconducting Transformer

Transformers are major components of power

systems. They allow generation, transmission, and

distribution of electrical energy at different voltage

levels, leading to economical benefits.

Replacing the copper windings in transformers by

a superconductor (SC) offers several opportunities.

First it offers reduction in losses, owing to the zero

resistance of the conductor. Second it offers reduc-

tion of size and weight. Because of higher current

densities, the mass of conductor needed can be very

small. By applying more winding turns/length in the

coils, the amount of iron can be reduced as well. Even

iron-free transformers might become feasible. Third,

large conventional power transformers are oil-cooled.

A superconducting transformer would be more envi-

ronmentally benign.

In a conventional transformer design the SC will be

exposed to alternating magnetic fields up to about

0.3 T. In designs with increased winding turns/length

(to reduce iron volume) an even higher magnetic field

(B) would be reached. The main challenges for the SC

material are high j

c

losses, low ac losses at high B, and

low cost. Since transformers generate losses not only

in the conductor but also in the iron core, it is ad-

visable to leave the core of an SC transformer at

room temperature, where cooling is cheaper. Such a

design however, poses serious requirements on the

cryostat, which would need a warm bore and should

ideally be made of nonmagnetic and electrically in-

sulating material in order to avoid additional losses.

1.1 Status of Research

Several SC transformers based on LTS have been

built in the past, having a rated power of a few

100 kV A. Commercially available LTS (low temper-

ature superconductor) wires meet technical and eco-

nomical needs (j

c

about 50 kA cm

2

, a.c. losses

o10

5

WA

1

m

1

at 0.1 T. However, commerciali-

zation of LTS transformers has so far been prohib-

ited by the rather high cooling costs, mainly caused

by thermal losses through cryostat and current leads.

HTS offers the opportunity to operate SC trans-

formers at 77 K, which could reduce cooling costs to

an acceptable level. But, HTS (high temperature su-

perconductor) wires are not nearly as mature as the

LTS wires. At present Bi2223 wire is the only HTS

available of sufficient length, which could be operated

at 77 K. First prototypes based on these materials

have been built. A 630 kV A prototype has already

been operated for one year under realistic conditions.

Even though the technical feasibility has been proven,

the present Bi2223 wire will hardly allow a commer-

cial SC transformer to be built.

At present the 77 K field dependence of j

c

(j

c

(B)), of

the wire is too strong and the a.c. losses and wire

costs are too high. J

c

(B) can be improved by oper-

ating the transformer at a lower temperature, which

of course increases cooling costs. Bi2223 conductors

with reduced a.c. losses are under development. The

1130

Superconducting Machines: Energy Distribution Component s

maximum acceptable losses are in the order of

10

4

WA

1

m

1

at 0.1 T; present values are about

10 times higher.

YBCO (YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7–x

) tapes, even though only

available at length of few meters, offer better j

c

(B)

and potentially lower cost. The a.c. losses in mag-

netic fields parallel to the YBCO tape will be negli-

gible. However, it will be a great challenge to reduce

the losses due to perpendicular field components

(occurring mainly at the end of the coils) to an ac-

ceptable value. Nevertheless, considering the status of

early twenty-first century technology, the material

seems to have the highest potential for transformer

applications.

2. Superconducting Fault Current Limiter

In electric power systems short circuits might be

caused by aged or accidentally damaged insulation

or by lightning striking an overhead line. The sub-

sequent fault current is only limited by the impedance

of the system between location of fault and power

sources. All components of the power system have to

be designed to withstand the stresses caused by a

short circuit. The higher the fault current anticipated,

the higher the costs for the equipment.

Many approaches for realising fault current limit-

ers (FCL) have been based on components with

strongly nonlinear current–voltage characteristics

(e.g., semiconductors, iron-core reactors, and super-

conductors). Among the nonlinear materials, super-

conductors stand out because of their unique

transition from zero to finite resistance. FCLs which

utilize this transition will be referred to as supercon-

ducting fault current limiters (SCFCLs). FCLs which

are based on other concepts but might still use SC,

e.g., in order to realize low-loss coils, will not be dis-

cussed here. There are essentially two concepts in

SCFCLs, i.e., the ‘‘resistive’’ and the ‘‘shielded core’’

concepts.

2.1 Resistive SCFCL

The most straightforward concept in an SCFCL is

the so called ‘‘resistive SCFCL’’ in which the SC is

directly connected in series to the line to be protected.

For cooling, the SC might be immersed in a coolant

(e.g., liquid helium for LTS or liquid nitrogen for

HTS), which is chilled by using a refrigerator.

The cross-section of the SC is determined such

that, at nominal current, the SC is operated inside the

superconducting state, i.e., at zero resistance, so that

its interference with the network is negligible. How-

ever, the SC only has true zero impedance for direct

current (d.c.)-currents. For the more common a.c.

applications the finite length of the SC leads to a

finite reactance and the alternating magnetic field

generated by the current produces a.c. losses. They

both depend very strongly on the geometry of the SC,

and can be reduced by optimized conductor archi-

tecture, e.g., in the coils with windings in opposite

directions or meander structures.

In case of a fault, the increase in j will drive the SC

out of the superconducting region into a flux–flow

regime. The rapidly increasing resistance limits the

current to a value below the unlimited prospective

fault current. The actual limitation behavior depends

very much on the length of the SC and also on the

type of SC material. The three main different limi-

tation behaviors can be realized by just varying the

length of the same SC material.

First, by using a very long conductor, the electric

field E ¼(line voltage)/(conductor length), to which

the SC is exposed during the fault will be very small.

Thus, the corresponding current density will exceed

the nominal value only by a little. The power density

E.

j

dissipated in the SC will be negligible so that the

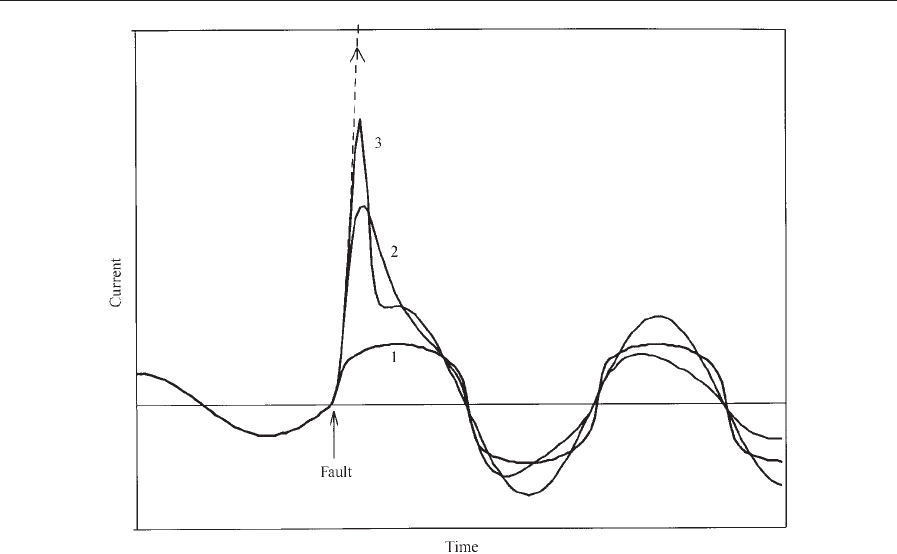

SC will essentially not warm up (curve 1 in Fig. 1).

This ‘‘constant temperature’’ design gives a very good

limitation. However, the long length of the conductor

will be prohibitively expensive and cause rather high

a.c. losses.

The other extreme design would be using a rather

short conductor, leading to a relatively large E during

the fault. As the fault occurs, the current will increase

essentially unlimited by the small resistivity of the

flux–flow regime and only limited by the impedance

of the power system. However, because of the very

high E.

j

dissipated in the SC, the material will heat up

rapidly and, after a few 100 ms, will become normal

conducting and limit the fault current close to or even

below the nominal value (curve 3 of Fig. 1). This

‘‘fast heating’’ design needs a rather small amount of

SC material. However, the height of the first peak still

depends on the unlimited prospective fault current,

and instantaneous recovery to normal operation is

not possible, since the SC first has to cool down.

Furthermore, severe over voltages may arise from the

abrupt current reduction, caused by the rapid tran-

sition into the normal-conducting state. Last, but not

least, the high E.

j

value during the fault might lead to

the SC being damaged.

Using a conductor of intermediate length will lead

to an intermediate poor density dissipation in the SC.

For the first 10 ms the maximum of the fault current

will be limited to several times (e.g., 5–10) that of the

nominal current. The SC will keep warming up and

after a few tens of milliseconds will enter the normal

conducting region (‘‘slow heating’’ design, curve 2 in

Fig. 1).

2.2 Hot Spots

In the above discussion it is assumed that during

the limitation process the voltage drop is uniform

over the whole length of the conductor. In reality,

1131

Superconducting Machines: Energy Distribution Components

however, SC tends to develop thermal instabilities

called ‘‘hot spots,’’ which are due to the strong cur-

rent and temperature dependence of their resistance.

The common measure for reducing the problem is to

attach a normal conducting ‘‘bypass’’ or ‘‘shunt’’ in

close electrical contact to the SC, which allows the

current to bypass the hot spot. Of course, the bypass

reduces the total normal resistance of the conductor,

which might have to be compensated by increased

length. It should be noted that the problem of exces-

sive heating will also limit the maximum possible

electric field to which the conductor can be exposed

during the fault, i.e., it will also set a lower limit for

the length of the SC.

2.3 Shielded Core SCFCL

The second concept in a SCFCL is often referred to

as the ‘‘shielded core.’’ In this concept the SC is not

connected galvanically in the line, but magnetically.

The device is essentially a transformer, with its pri-

mary normal conducting coil connected in series to

the line to be protected, while the secondary side is a

superconducting tube (i.e., a one turn coil). In normal

operation the iron core sees no magnetic field because

it is completely shielded by the SC, thus the name

‘‘shielded core.’’ Because of the inductive coupling

between the line and the SC, the device is sometimes

also referred to as an ‘‘inductive SCFCL.’’ The volt-

age on the secondary is reduced by the number of the

turns of the primary coil, while the current is in-

creased by the same factor. The SC on the secondary

has to be designed for these values. Assuming an

ideal transformer, the SCFCL will behave exactly like

a resistive SCFCL.

In order to achieve a certain limitation behavior,

both types of SCFCL need the same amount of a

certain SC material. Compared to the resistive

SCFCL, the shielded core SCFCL shows the disad-

vantage of being only applicable for a.c. currents and

having a much larger size and weight. On the other

hand it needs no current leads, which is especially

attractive for high current applications, since the

losses of the leads are proportional to their current-

carrying capability.

2.4 Status of Research

Several SCFCL prototypes with a rated power of

several MVA have been realized based on LTS fol-

lowing the resistive concept. Because of the high j

c

and low heat capacity of LTS the ‘‘fast heating’’ de-

sign was the ‘‘natural’’ choice. However, like in the

Figure 1

Different designs offer different current limitation behaviors. 1, Constant temperature; 2, slow heating; 3, fast heating.

1132

Superconducting Machines: Energy Distribution Component s

case of the transformer, commercialization has so far

been prohibited by the rather high cooling costs.

To date, the largest HTS SCFCL prototype that

has been built utilizes Bi-2212 bulk material. ABB

has realized a three-phase 1.2 MV A prototype based

on tubes of this material. For ceramic HTS, this ge-

ometry is usually more easily realized than long

length conductors. The device is of the ‘‘shielded

core’’ and ‘‘slow heating’’ type, it was successfully

operated for one year under realistic conditions in a

Swiss hydropower plant.

Because of their high critical current density

(1 MA cm

2

) YBCO films are especially suitable for

the ‘‘fast heating design.’’ Siemens has demonstrated

a resistive 300 kV A model based on this material.

The films were deposited on planar ceramic subst-

rates, covered with a gold bypass, and patterned into

meander.

Bi2223 wires are at present not particularly suitable

for SCFCL, because of the low normal resistivity of

the Ag-matrix. However, if this resistivity could be

increased, the wire would be quite suitable for resis-

tive SCFCL and could even allow for the incorpo-

ration of ‘‘current limitation’’ functionality in other

devices. Following this approach, a project led by

ABB in partnership with American Superconduc-

tor and Electricite

´

de France has been launched to

develop a current limiting transformer.

See also: Superconducting Machines: Energy Storage

Bibliography

Fevrier A, Tavergnier J P, Laumond Y, Bekhaled M 1988 Pre-

liminary test on a superconducting power transformer. IEEE

Trans. Magn. 24, 1477–80

Gromoll B, Ries G, Schmidt W, Kraemer H P, Seebacher B,

Utz B, Nies R, Neumueller H W, Balzer E, Fissher S, Heis-

mann B 1999 Resistive fault current limiters with YBCO

films–100 kV A functional model. IEEE Trans. Appl. Super-

cond. 9, 656–9

Hoernfeldt S, Albertsson O, Bonmann D, Koenig F 1993 Power

transformer with superconducting windings. IEEE Trans.

Magn. 29, 3556–8

Paul W, Chen M 1998 Superconducting control for surge cur-

rents. IEEE Spectrum May, 49–54

Paul W, Lakner M, Rhyner J, Unterna

¨

hrer P, Baumann Th,

Chen M, Widenhorn L, Gue

´

rig A 1997 Test of 1.2 MV A

high-T

c

superconducting fault current limiter. Supercond. Sci.

Technol. 10, 914–8

Schwenterly S W, McConnel B W, Demko J A, Fadnek A, Hsu

J, List F A, Walker M S, Hazelton D W, Murray F S, et al.

1999 IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 9, 680–4

Seeber B (ed.) 1998 Handbook of Applied Superconductivity IOP

Publishing, Vol. 2, pp. 1613–26 and 1691–1702

Verhaege T, Cottevieille C, Estop P, Quemener M, Tavergnier J

P, Bekhaled M, Bencharab C, Bonnet P, Laumond Y, Pham

V D, Poumarede C, Therond P G 1996 Experiments with a

high voltage (40 kV) superconducting fault current limiter.

Cryogenics 36, 521–6

Yazawa T, Yoneda E, Nomura S, Tsurunaga K, Urata M,

Ohkuma T, Honjo S, Iwata Y, Hara T 1997 Experiments

with a 6.6 kV A/1 kA single-phase superconducting fault cur-

rent limiter. In: Rogalla H, Blank D H A (eds.) Proceedings

of EUCAS 1997, Third European Conference on Applied

Superconductivity. Institute of Physics Conference Series

Number 158. Institute of Physics, Bristol, Vol. 2, pp. 1183–6

Zueger H 1998 630 KVA high temperature superconducting

transformer. Cryogenics 38, 1169–72

W. Paul

ABB Corporate Research Ltd, Baden-Daettwil

Switzerland

Superconducting Machines: Energy

Storage

Superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) is

an emerging technology offering tremendous benefits

to the electric power industry. Many years after its

conception (Ferrier 1970), SMES is still not widely

implemented and its commercial viability is only

slowly being established.

1. Principles of Operation

Electric power has always been available on instant

demand with a high degree of reliability, flexibility,

and control; however, it has never been easy to store

in large quantities on a cost-effective and environ-

mentally sound basis.

In SMES, electric energy is stored by circulating a

current in a superconducting coil, or inductor. Be-

cause no conversion of energy to other forms is in-

volved (e.g., mechanical or chemical), round-trip

efficiency can be very high. The energy stored in a d.c.

inductor is given by

E ¼

1

2

LI

2

ð1Þ

where E is the stored energy, L is the inductance of

the coil (which depends on coil geometry), and I is the

circulated current.

As an energy storage device, SMES is a relatively

simple concept. It stores electric energy in the mag-

netic field generated by d.c. current flowing through a

coiled wire. If the coils were wound using a conven-

tional wire such as copper, the magnetic energy

would be dissipated as heat owing to the resistance of

the wire. However, if the wire is superconducting (no

resistance), then energy can be stored in a persistent

mode, virtually indefinitely, until required.

The SMES coil, a d.c. device, is usually connected

to its load (typically an a.c. device) via an a.c./d.c.

converter, or ‘‘power conditioning system’’ (PCS).

1133

Superconducting Machines: Energy Storage

The architecture of the PCS varies depending on the

application, but in general is based on standard semi-

conductor power switches in arrangements to max-

imize reliability, efficiency, and controllability.

The only loss associated with magnetic storage is

the power needed to keep the coil cryogenically

cooled as required by the superconductor. Addition-

ally, there are minor losses associated with power

transfers through the a.c./d.c. converter. Overall ef-

ficiency of a SMES system is heavily dependent on

size (stored energy) and power rating, as well as on

duty cycle, but in general SMES units can be much

more efficient than many other systems for energy

storage.

2. Applications

In terms of energy storage, SMES competes with

other technologies such as batteries, flywheels, and

capacitors. The choice of technology is determined by

economics (cost) when considering all angles: system

performance, capital and operating costs of the unit,

reliability and maintainability, environmental and

disposal costs, insurance, etc.

SMES is particularly attractive in comparison to

other options in cases where a high power/energy ra-

tio is needed (sharp pulses), or when the power pulse

repetition rate is high (e.g., tens or even hundreds of

pulses per day).

Pulsed power loads such as electromagnetic launch

(for military or space applications) could be enabled

through the implementation of a SMES system. Buff-

ering pulsating loads in general is a high-payoff

application of SMES.

In the electric power sector SMES has two major

applications: power quality enhancement, and trans-

mission-related services. Power quality enhancement

refers to the ability of SMES systems to sit idle and

connected between a load and its utility supply line to

‘‘buffer’’ and ‘‘filter’’ power quality disturbances such

as voltage sags and spikes, harmonic distortions, or

frequency problems coming through the utility dis-

tribution network. Certain applications needing very

sensitive loads (such as is required in semiconductor

processing plants) can derive great benefit from ac-

cess to ‘‘clean’’ power and thus pay the premium in

price over other storage technologies. At the lower

end of stored energy and power (a few megajoules

and few megawatts) this is already a commercial ap-

plication of SMES, with the prospect of capturing a

larger market with the development of larger units.

The electric utility industry, being deregulated in

most parts of the world, could also be major market

for this technology. The applicability of SMES to the

utility sector goes well beyond energy storage (daily

load leveling). Some of these applications are:

*

increased transmission capacity through enhan-

ced line stability;

*

spinning reserve;

*

leveling of renewable energy sources;

*

voltage control;

*

frequency control;

*

subsynchronous frequency damping;

*

wide-area generation control; and

*

black start.

Power and energy ratings needed for each of these

application vary, from a few hundred megajoules to

provide transmission line stabilization, to possibly

many gigajoules in the case of spinning reserve for a

large network.

In transmission stabilization, a SMES unit is stra-

tegically located within a high-voltage network to in-

ject active and/or reactive power on demand to

dampen voltage fluctuations that can cause the trig-

gering of protective relays. These fluctuations are

usually the result of large generation plants or loads

tripping and creating instabilities that cause large-ar-

ea blackouts. In spinning reserve a SMES unit can act

as a infinitely controllable generating unit (with the

added benefit of also acting as a ‘‘sink’’) to enhance

flexibility of dispatch and to provide that extra cush-

ion need to run a transmission network without the

need of having ‘‘idling’’ plants with the concomitant

environmental penalty.

In a fully deregulated utility industry (something

not yet achieved) SMES will be an integral part of the

network.

3. Technology Development

The status of SMES in terms of its development and

application has been reviewed by Hassenzahl (1989)

and by Luongo (1996). The early years of SMES

development were mostly devoted to system studies

and to determining optimum configurations. During

the 1980s the technology saw an increase in activity

with the implementation of programs that led to

actual hardware being produced. During the 1990s

there was somewhat of a retrenchment in terms of

development, with relatively few full demonstration

programs.

In the early 1980s a 30 MJ SMES unit was installed

and tested at the Bonneville Power Authority trans-

mission grid in the USA to demonstrate its ability to

dampen subsynchronous resonant frequencies (Rog-

ers et al. 1983). Also during the 1980s the US De-

partment of Defense funded the design and

development of components needed to build a

large-scale SMES units that would serve as pulsed

power supplies to military systems. These activities

yielded a number of advances in terms of innovative

designs and the actual fabrication and testing of ma-

jor SMES components. Among the advances was the

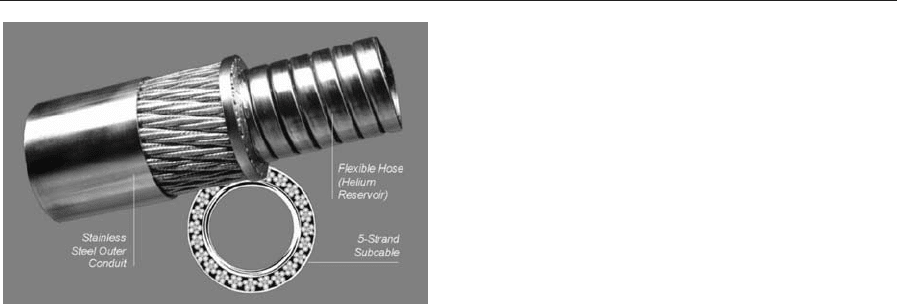

development of a very high-current cable-in-conduit

conductor, shown in Fig. 1, rated at 200 kA (at 1.8 K

and 5 T), and which was actually tested in short

1134

Superconducting Machines: Energy Storage

samples under operating condition to its quench cur-

rent of 300 kA (Peck et al. 1994).

In the 1990s most of the development activity took

place in Japan with a focus on transmission stability

applications as well as the construction and testing of

a large SMES model coil (Hamajima 1999).

Previous experience with SMES notwithstanding,

it is safe to say that this technology is still in need of

an integrated large-scale demonstration under actual

operating conditions (e.g., utility environment) be-

fore its widespread acceptance in the market.

4. Outlook

Despite its great promise and many years of devel-

opment, SMES is far from being the commercial

success once envisioned. Even though the technology

is making some inroads into the marketplace (at the

lower end of storage/power ratings), it is far from

mature or being widely accepted. The main stumb-

ling block for wider dissemination of SMES is not

technical, but rather economic. The extremely high

cost of superconducting devices does not justify the

economic benefits that could be accrued in most ap-

plications. The advent of high-temperature supercon-

ductor (HTS) materials has done little to advance the

deployment of SMES. Major reductions in the price

of these superconductors would be needed before

they can make an impact on the commercial viability

of SMES. Operation at higher temperature alone

does not justify adoption of HTS materials, as

operating costs are typically a small component of

lifecycle cost for SMES units of practical size.

Continued advances in SMES technology are

nevertheless likely. One-of-a-kind units for specific

applications will give SMES opportunities to demon-

strate its benefits. Through this evolutionary chain of

development SMES will some day take its promised

role in the electric power industry.

See also: Superconducting Permanent Magnets: Po-

tential Applications; Superconducting Permanent

Magnets: Principles and Results

Bibliography

Ferrier M 1970 Stockage d’energie dans un enroulement sup-

raconducteur. Low Temperature and Electric Power. Perga-

mon, Oxford, UK , pp. 425–32

Hamajima T 1999 Test results of the SMES model coil—pulse

performance. Cryogenics 39, 351–7

Hassenzahl W V 1989 Superconducting magnetic energy stor-

age. IEEE Trans. Magnetics 25, 750–8

Luongo C A 1996 Superconducting storage systems: an over-

view. IEEE Trans. Magnetics 32, 2214–23

Peck S D, Zeigler J, Luongo C A 1994 Tests on a 200 kA cable-

in-conduit conductor for SMES. IEEE Trans. Appl. Super-

cond. 4, 199–204

Rogers J D, et al. 1983 30-MJ SMES system for electric utility

transmission stabilization. Proc. IEEE 71, 1099–107

C. A. Luongo

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

Tallahassee, Florida, USA

Superconducting Materials, Types of

In 1911 the Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh

Onnes (Onnes 1911) observed during studies of the

electric properties of pure metals at temperatures

near absolute zero (0 K or 273.15 1C), that the re-

sistance of a mercury wire dropped precipitously

when cooled to below 4.2 K (268.95 1C). He soon

recognized this to be the manifestation of a new state

of matter ‘‘which on account of its extraordinary

electrical properties may be called the superconduct-

ing state.’’

For over 20 years after the discovery of supercon-

ductivity, this new state was believed to be just an

ideal conductor that loses its resistance below a dis-

tinct temperature, the so-called critical temperature,

T

c

. In the year 1933, Meissner and Ochsenfeld (1933)

discovered that magnetic fields are excluded from the

inside of a superconductor even on cooling in a con-

stant magnetic field that could not be explained by

classical electrodynamics. This effect is known today

as the Meissner–Ochsenfeld effect.

Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer published their

comprehensive theory of superconductivity in 1957

(Bardeen et al. 1957). The salient point of the so-

called BCS theory is the attractive electron inter-

action mediated by phonons. By that virtue, two

electrons couple to form so-called Cooper pairs,

which act in a fundamentally different way from

single electrons. Being quasi-particles with integer

spin, Cooper pairs follow the Bose–Einstein statistics

Figure 1

High-current cable-in-conduit conductor.

1135

Superconducting Materials, Types of

which allows them to condense into a single quan-

tum mechanical state, with all Cooper pairs having

the same wave function. Thus, superconductivity is

often referred to as a macroscopic quantum phe-

nomenon. The BCS theory was very successful

in predicting the critical temperature of a material

and provided an explanation for the isotope effect,

according to which the critical temperature shifts

as a function of the isotopic mass of chemical

elements.

With the discovery of materials showing transition

temperatures near and above 100 K, it became evident

that the BCS theory would not be adequate to des-

cribe this new class of superconductors, known as

high-temperature superconductors, in contrast to the

term ‘‘low-temperature superconductor’’ which com-

prises all superconductors with critical temperatures

below about 30 K. Experiments gave evidence that the

charge carriers of superconductivity are Cooper pairs.

But, the question about the nature of the force that

keeps the Cooper pairs together is still a matter of

investigation.

Since the first observation of superconductivity in

mercury, thousands of compounds and alloys were

investigated with respect to their superconducting

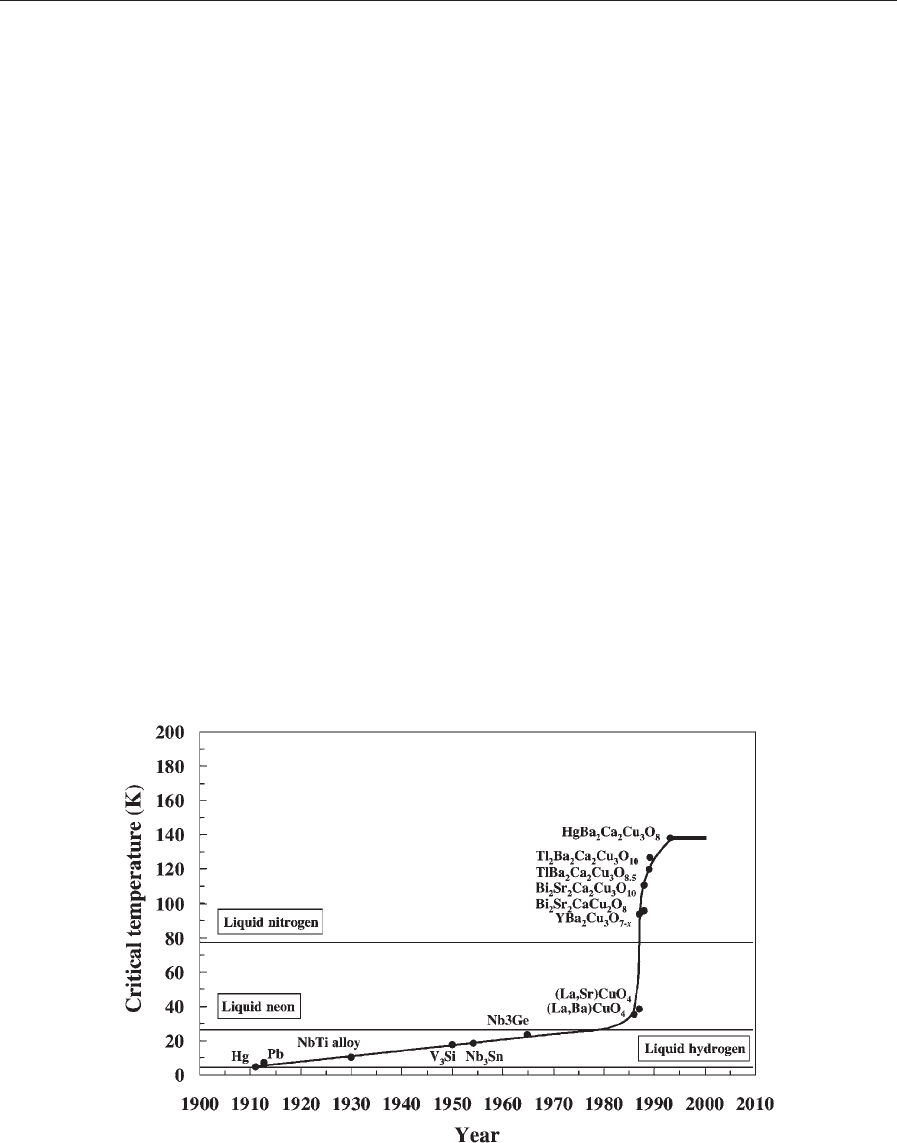

properties. In Fig. 1 the fever curve of superconduc-

tivity is shown, which is marked by the highest critical

temperature known during that time. Since 1993,

several new superconductors have been found. None

of them, however, have surpassed the world cham-

pion HgBa

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

8

exhibiting a T

c

of 138 K at

ambient pressure, and 164 K at an isostatic pressure

of 23 GPa.

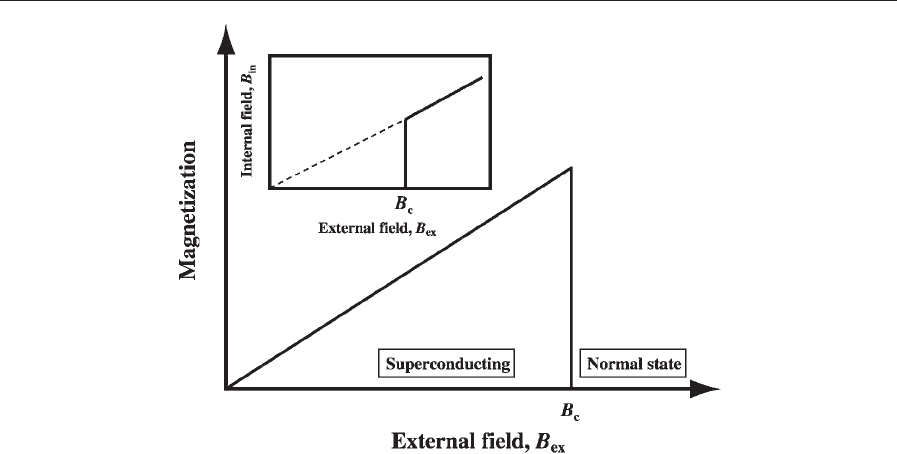

1. Type 1 Superconductors

Type 1 superconductors—also known as the ‘‘soft’’

superconductors—are characterized by a very sharp

transition to a superconducting state at T

c

, and by

‘‘perfect’’ Meissner–Ochsenfeld effect up to the so-

called critical field, B

c

. Above B

c

, the material be-

comes normal conducting. Even here, the transition is

very sharp (Fig. 2). The value of B

c

is temperature

dependent and reaches zero at T

c

. However, the

magnetic field is not repelled at the surface of the

superconductor, but penetrates it within a 10

8

–10

7

m thick surface layer causing screening electric cur-

rents in the surface layer. These currents generate a

magnetic field which is anti-polarized to the external

field. This phenomenon is the reason for the well-

known levitation effect of a permanent magnet above

a superconductor, or vice versa.

The so-called penetration depth, l, of the external

magnetic field is a material property. It also is

temperature dependent and increases asymptotically

towards T

c

. At the particular field B

c

relatively

thick normal and superconducting domains running

parallel to the field can coexist, known as the inter-

mediate state.

2. Type 2 Superconductors

Type 2 superconductors—also known as the ‘‘hard’’

superconductors—differ from Type 1 in that their

transition from a normal to a superconducting state

is gradual across a region of ‘‘mixed state’’ behavior.

Figure 1

Maximum critical temperature vs. time.

1136

Superconducting Materials, Types of

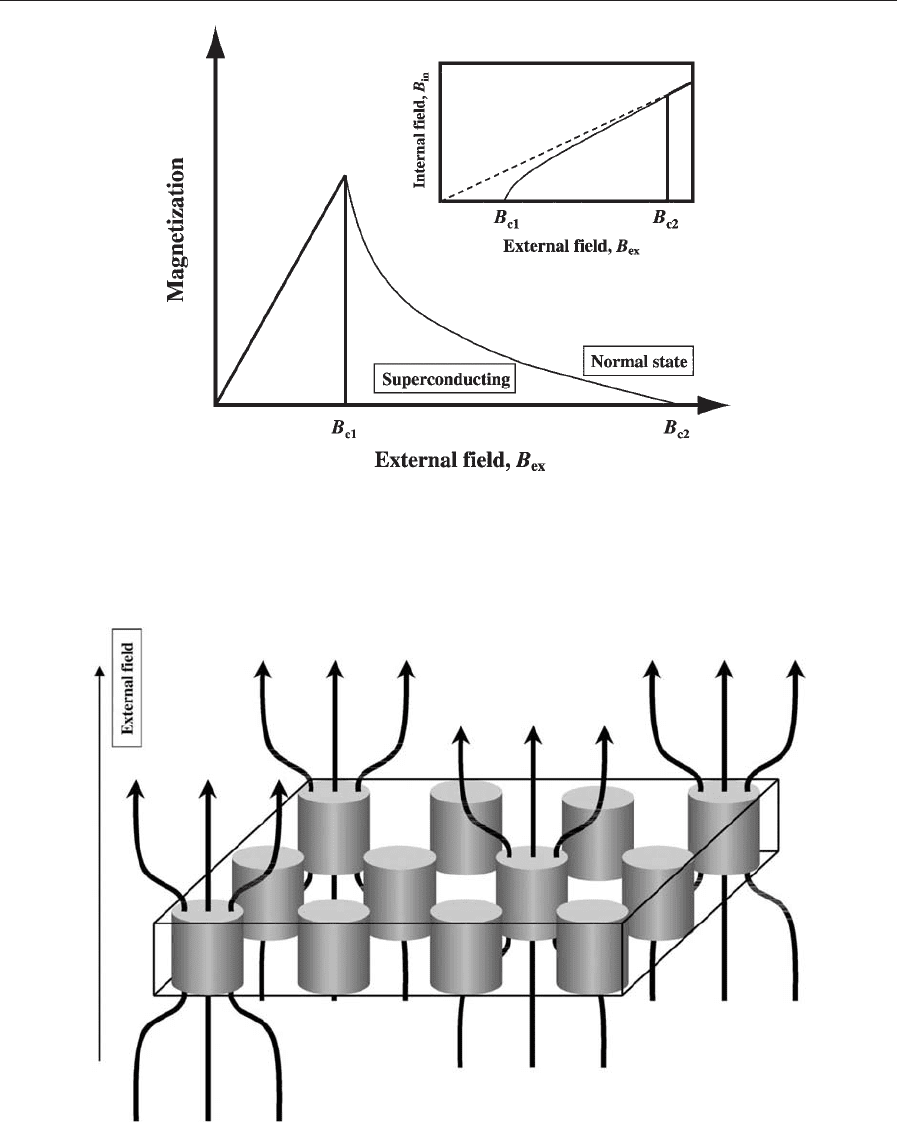

A Type 2 superconductor exhibits a very different

behavior in an external magnetic field compared to

the Type 1 superconductors. At low external fields,

like the Type 1 superconductor it repels the magnetic

field up to the lower critical field, B

c1

. This region is

also called the ‘‘Meissner phase.’’ Above B

c1

, regu-

larly divided quantified flux vortices or flux lines enter

the material up to the so-called upper critical field,

B

c2

(Fig. 3). In the region between B

c1

and B

c2

, su-

perconducting and nonsuperconducting areas with

trapped magnetic flux lines are present (Fig. 4). With

increasing magnetic fields, the trapped flux lines move

closer together and more trapped flux lines occur, so

that the superconducting volume decreases and that

of the nonsuperconducting increases (see Electrody-

namics of Superconductors: Flux Properties). The re-

gion is called the ‘‘Shubnikov phase’’ or the mixed

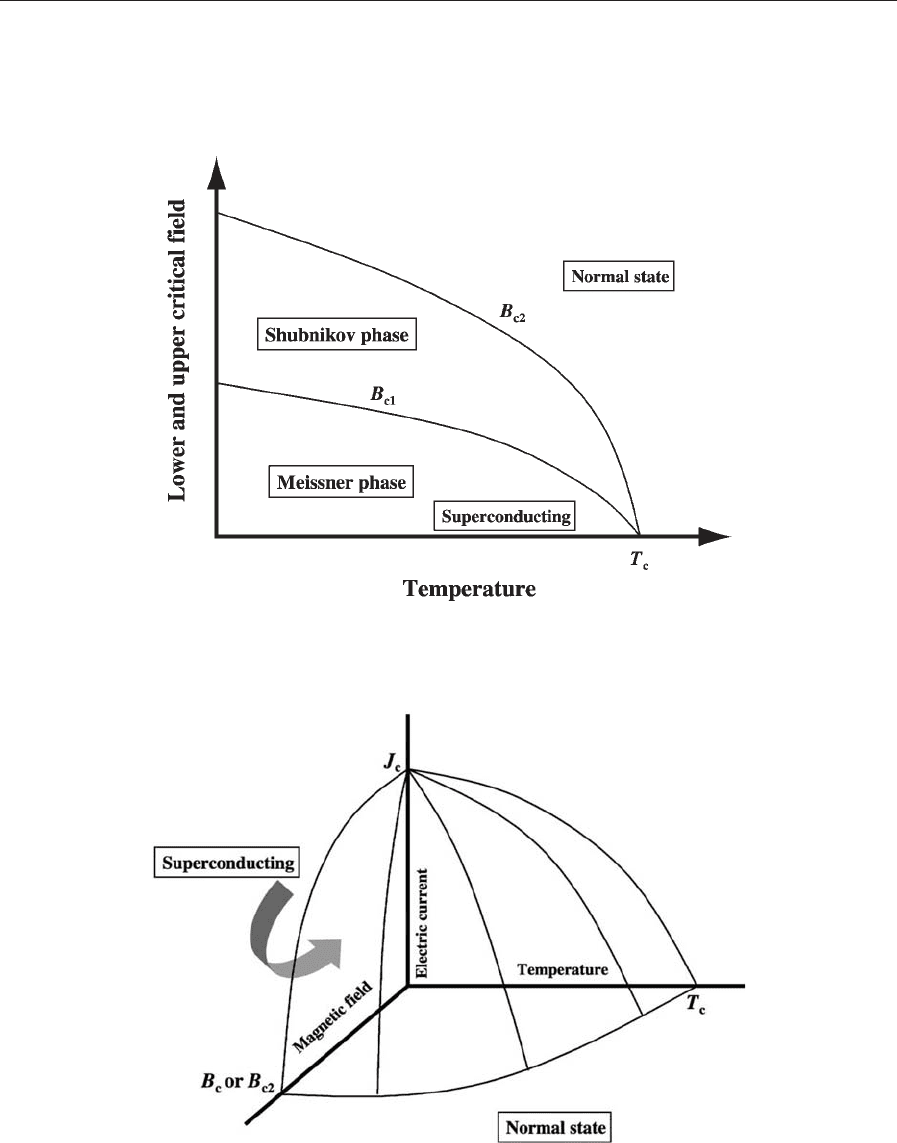

state. The values of B

c1

and B

c2

are also temperature

dependent and decrease with increasing temperature.

At T

c

both values, B

c1

and B

c2

, are zero (Fig. 5).

3. Critical Current Density

Both categories of superconductors, Types 1 and 2,

can carry large electric currents up to a certain value

which is called the critical current density, J

c

(A cm

2

). Above J

c

, the superconductor becomes

normal conducting. J

c

is dependent on both the tem-

perature and the external magnetic field. At T

c

or B

c

(Type 1) or B

c2

(Type 2) the value of J

c

is zero and the

superconductor becomes normal conducting (Fig. 6).

Superconductors show characteristic current vs. volt-

age behavior. At a current below J

c

the voltage is

zero. Above J

c

, as in a metal, the voltage increases

with the current (Fig. 7).

In the mixed state, when an electric current is

transported through the superconductor due to the

Lorenz force, the trapped flux lines can move through

the superconductor causing dissipation of the current

and a warming of the superconductor. This phenom-

enon can result in a rapid transition into the normal

conducting state. Therefore, the value of J

c

is signi-

ficantly lower in the Shubnikov phase compared to

the Meissner phase. However, the flux lines can be

pinned by so-called pinning centers, which are defects

with different dimensions within the superconductor.

For example, point defects (zero dimension), dislo-

cation lines (one dimension), twin planes (two di-

mensions), and second phases (three dimensions).

The flux lines remain pinned until the Lorenz force

surpasses the pinning force of the defect.

4. Superconducting Materials

Except for the elements vanadium, technetium, and

niobium, the Type 2 category of superconductors in-

cludes compounds and alloys. Niobium (T

c

¼ 9:2 K),

especially when alloyed with titanium (Nb0.7Ti0.3:

T

c

¼ 9:8 K), exhibits the highest critical temperature

of all elements. Although superconductors with higher

Figure 2

Magnetization of a Type 1 superconductor vs. the external field, B

ex

. Insert: Magnetic field within a Type 1

superconductor, B

in

, vs. the external field, B

ex

.

1137

Superconducting Materials, Types of

Figure 3

Magnetization of a Type 2 superconductor vs. the external field, B

ex

. Insert: Magnetic field within a Type 2

superconductor, B

in

, vs. the external field, B

ex

.

Figure 4

Type 2 superconductor with trapped flux lines vortex.

1138

Superconducting Materials, Types of

T

c

are available, until now, most commercially avail-

able superconducting magnets operating below about

5 T are based on NbTi wires, due to its compara-

bly low price and excellent manufacturing qualities.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, compounds

were found with T

c

values in the range of 10–20 K.

These compounds belong to the b-tungsten structure

family, also named A15 phases or A

3

B structure. The

unit cell of the structure consists of a cube with the B

atoms entering each corner of the cube. The A atoms

Figure 5

Lower and upper critical field of a Type 2 superconductor vs. the temperature.

Figure 6

Critical current density, J

c

, vs. the temperature and the external magnetic field.

1139

Superconducting Materials, Types of