Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

above). The large jump in the Mn moment at T

N

leads to a large jump in the volume, and concurrently

to a large thermal hysteresis (E20 K), clearly indi-

cating a first-order transition. For T4T

N

, a large

thermal expansivity is found. This is ascribed to spin

fluctuations in the (paramagnetic) Mn subsystem. On

the basis of a combined analysis of specific-heat data

and thermal-expansion for the related alloying system

(Nd,Lu)Mn

2

, Kim-Ngan et al. (1994) succeeded to

separate the contribution of the spin fluctuations

from the lattice contribution and other, electronic,

contributions (Fig. 6). The excess volume is assumed

to be due to the magnetic Mn moment. When for the

antiferromagnetically ordered Mn-system at low

temperatures the Mn moment is taken as 2.7 m

B

/

Mn, the mean fluctuating Mn moment would be

B2.5 m

B

/Mn at room temperature. So, the fluctuating

Mn moments are quite comparable with local atomic

moments (of fixed magnitude).

See also: Electron Systems: Strong Correlations;

Itinerant Electron Systems: Magnetism (Ferromag-

netism); Magnetoelastic Phenomena; Metamagnet-

ism: Itinerant Electrons

Bibliography

Aguayo A, Mazin I I, Singh D J 2004 Why Ni

3

Al is an itine-

rant ferromagnet but Ni

3

Ga is not. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92,

147201

1–4

Brommer P E, Franse J J M 1990 Strongly enhanced itinerant

intermetallics and alloys. In: Buschow K H J, Wohlfarth E P

(eds.) Ferromagnetic Materials. Elsevier (North-Holland),

Amsterdam, Vol. 5, pp. 323–96

Duc N H, Brommer P E 1999 3D-Moments and spin fluctu-

ations in some rare-earth – cobalt compounds. In: Buschow

K H J (ed.) Handbook of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier,

Amsterdam, vol. 12, pp. 259–394

Jullien R, Be

´

al-Monod M T, Coqblin B 1974 Resistivity of

nearly magnetic metals at high temperatures: Application to

neptunium and plutonium. Phys. Rev. B 9, 1441–57

Kaul S N 1999 Spin fluctuation theory for weak itinerant-elec-

tron ferromagnets: revisited. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 11,

7597–614

Kim-Ngan N H, Brommer P E, Franse J J M 1994 Spin fluc-

tuations in the (Nd,Lu)Mn

2

system. IEEE Transactions on

Magnetics 30, 866–8

Moriya T 1985 Spin Fluctuations in Itinerant Electron Magnet-

ism. Springer, Berlin

Nakada K, Shimizu H, Yamada H, Harima H 2004 Mag-

netic properties and Fermi surface of YMn

2

. J. Magn. Magn.

Mater. 262, 374–81

Semwal A, Kaul S N 2002 Effect of site disorder on the as-

ymptotic critical behaviour of Ni

75

Al

25

. J. Phys.: Condens.

Matter 14, 5829–47

Shimizu M 1981 Itinerant electron magnetism. Rep. Prog. Phys.

44, 329–409

Takahashi Y 2001 Quantum spin fluctuation theory of the

magnetic equation of state of weak itinerant-electron ferro-

magnets. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13, 6323–58

Yamada H, Fukamichi K, Goto T 2003 Recent advances of

itinerant-electron metamagnetism and related properties of

intermetallic compounds. Physica B 327, 148–54

P. E. Brommer

Van der Waals-Zeeman Instituut, Universiteit van

Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Spin Transitio n Compounds

Octahedral complexes of transition metal ions with

configurations d

4

d

7

exist in either the high-spin

(HS) or low-spin (LS) state, depending on the nature

of the ligand field. In weak fields the ground state is

HS, the d electrons being distributed over the t

2g

and

e

g

sets, whereas strong fields stabilize the LS state, the

t

2g

set being completely occupied before electrons are

added to the e

g

set (Fig. 1). For iron(II), for example,

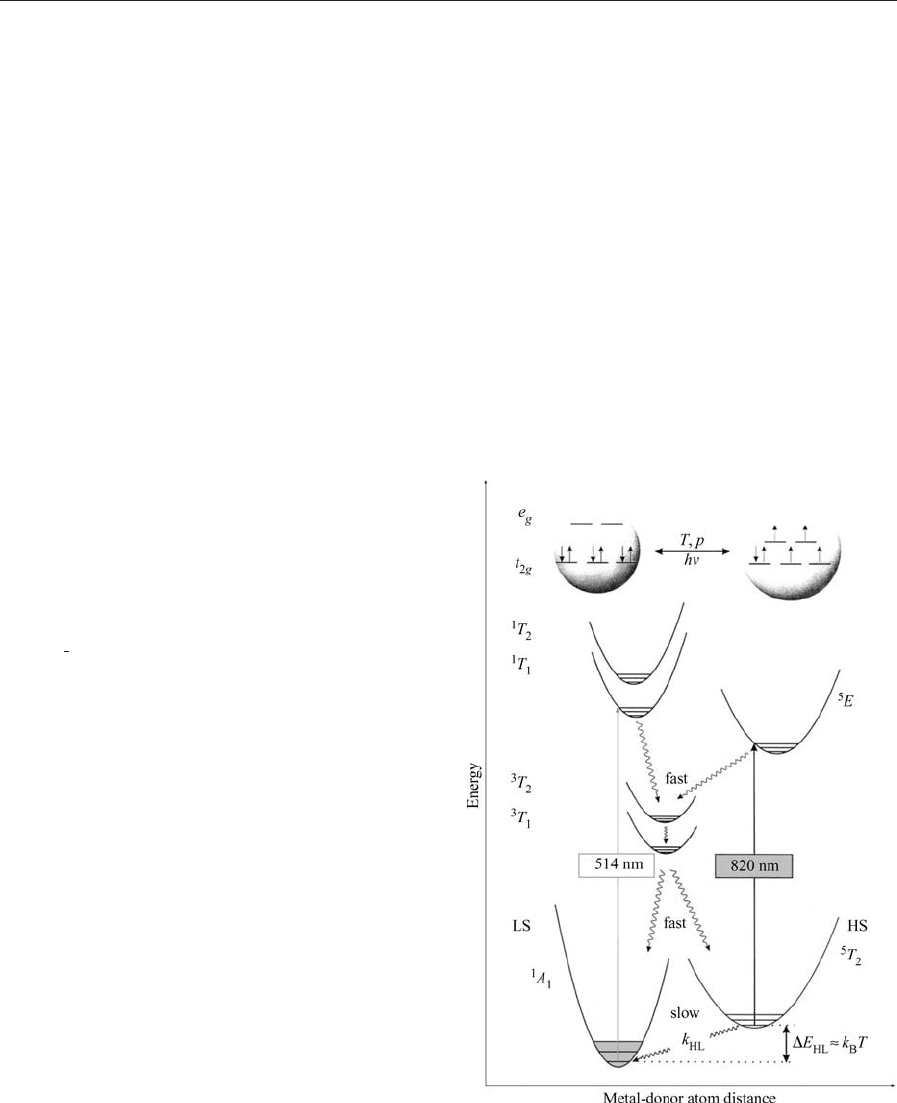

Figure 1

Representation of the interconversion of HS and LS

states for iron(II) and the mechanism of the LIESST

effect.

1100

Spin Transition Compounds

the two states are illustrated by [Fe(H

2

O)

6

]

2 þ

, con-

figuration (t

2g

)

4

(e

g

)

2

, and [Fe(CN)

6

]

4

, configuration

(t

2g

)

6

. For intermediate fields the energy difference

between the lowest vibronic levels of the potential

wells of the two states may be sufficiently small such

that application of some relatively minor external

perturbation effects a change in the state. This phe-

nomenon is known as a spin transition (ST) or spin

crossover. Materials which display STs are of interest

because of their potential in electronic devices for

applications such as data storage and displays. The

first transitions were observed in the 1930s in

iron(III) dithiocarbamates and these were later ex-

tensively studied in the 1960s (Martin and White

1968). Although STs have been observed for all the

configurations d

4

d

7

for the first transition series,

the greatest number has been reported for iron(II)

(Gu

¨

tlich et al. 1994).

1. Occurrence and Detection of Spin Transitions

A change in spin state effects fundamental changes in

the electronic configuration and thus will affect all

those properties of the system which depend on elec-

tronic structure. The most important of these are

magnetism, color, and structure. In HS Fe

II

, electrons

partly occupy both the antibonding e

g

set and the

nonbonding or weakly bonding t

2g

set, whereas in LS

Fe

II

only the t

2g

set is occupied. This allows closer

approach of the donor atoms in the LS state and

hence a HS-LS spin transition is accompanied by a

significant structural change involving a contraction

in the metal–donor atom distances of about 0.2A

˚

or 10%. For solid systems this change in molecular

dimensions may bring about fundamental changes

in the crystal lattice. For this reason STs in solid

systems can follow a number of different paths. These

differ principally in the degree of cooperativity

associated with the transition. When this is low the

transition will be gradual or continuous, but as coop-

erativity increases the transition becomes more

abrupt and may be associated with a phase change

and hysteresis. In some instances two-step transitions

have been observed, while in others residual fractions

of HS or LS species persist at the extremities of the

transition.

An ST may be monitored and an ST curve (HS

fraction vs. T) constructed by a variety of techniques.

The curve reflects the nature of the change in pop-

ulation of the HS state with change in temperature.

For iron(II), Mo

¨

ssbauer spectroscopy is particularly

suitable for characterizing an ST since the spectral

parameters associated with the HS and LS states

clearly differ and the timescale of the technique gen-

erally allows the detection and evaluation of the sep-

arate spin states in the course of the transition.

Although the criterion for the occurrence of an ST

may appear very restrictive, a large number (4150)

of systems have been characterized. The majority are

Fe

II

N

6

systems involving heterocyclic donors. The

first synthetic system, Fe(phen)

2

(NCS)

2

(phen ¼1,10-

phenanthroline), was identified by Ko

¨

nig and Madeja

(1966). Since then many species of similar composi-

tion have been shown to undergo transitions. In ad-

dition, derivatives of simple unidentate ligands such

as isoxazole and tetrazoles, along with multidentate

and polynuclear systems are known. Two strategies

are widely effective in fine-tuning the field strength of

model ligands so as to bring it into the crossover

region:

(i) Incorporation of chemical substituents. If the

substituent is adjacent to a donor atom this will de-

stabilize the singlet state by hindering the close ap-

proach of the metal atom and is illustrated by

[Fe(mephen)

3

]

2 þ

(mephen ¼2-methyl-1,10-phenan-

throline) which is HS at room temperature but

undergoes a transition to LS at low temperatures,

in contrast to the unsubstituted [Fe(phen)

3

]

2 þ

which

is LS. Where the substituent is remote from the donor

atom electronic effects may stabilize either state.

(ii) The replacement of six-membered heterocycles

by five-membered ones. The principal effect here is to

reduce both the s-donor and p-acceptor character of

the system, thus favoring the quintet state, illustrated

by the spin crossover behavior of [Fe(pyim)

3

]

2 þ

(pyim ¼2-(pyridin-2-yl)imidazole), in contrast to the

completely LS nature of [Fe(bpy)

3

]

2 þ

(bpy ¼2,2

0

-

bipyridine).

2. Solution and Solid-state Behavior

STs are observed for systems in both solution and

solid states, though the one system will not necessar-

ily display a transition in both phases. In solution,

interactions between the molecules undergoing spin

change are virtually negligible and thus the course of

the transition can be described by a Boltzmann dis-

tribution over all HS vibronic states and the LS state.

The driving force for the transition is the considerable

entropy gain of B50–80 J mol

1

K

1

for the LS-HS

conversion, made up of a magnetic component,

DS

mag

¼R[ln(2S þ1)

HS

ln(2S þ1)

LS

],

B13 J mol

1

K

1

, and a larger vibrational entropy

contribution arising from the much higher degener-

acies in the HS state. The enthalpy change for the

LS-HS conversion is typically 6–15 kJ mol

1

and

is associated primarily with rearrangement of the co-

ordination sphere (metal–donor atom bond length

increase). In the solid state there is electron–phonon

coupling between the molecules changing spin state,

resulting in cooperative interactions of varying

degrees.

One of the most successful models for ST behavior

takes as its basis the change in the metal–donor

atom distance accompanying a transition (Spiering

and Willenbacher 1989). It is proposed that such a

1101

Spin Transition Compounds

significant change at every ‘‘point defect’’ where an

ST occurs sets up pressure (an ‘‘image pressure’’)

which is communicated to the surroundings via pho-

non interactions. In the course of the ST, at many

point defects the lattice expands and accelerates the

ST in other metal centers. Thus, the nature of

the cooperative interactions in a solid is elastic, and

the model uses typical quantities from elasticity the-

ory, e.g., bulk modulus and Poisson ratio, to account

for the experimental results.

3. Effect of Pressure

The effect of increased pressure is to favor the HS-

LS conversion because of the smaller volume of the

LS form. From both solution studies and crystal

structure determinations, DV has been estimated as

typically 50A

˚

3

per octahedral unit. The study of the

effects of high pressure on the course of STs in solid

samples has revealed some subtle effects which in-

clude displacement of the transition temperature,

change in the width of the hysteresis loop, and

changes in the residual fractions of HS and LS species

at the extremes of the temperature range for the

transition (Ksenofontov et al. 1999).

4. Effect of Light

It has been observed that an Fe

II

spin crossover

compound in the LS state is converted by light into

the metastable HS state with virtually infinite lifetime

at sufficiently low temperatures (Decurtins et al.

1984). This phenomenon became known as the light-

induced excited spin state trapping (LIESST) effect.

Later it was found that the reverse process is also

possible. The mechanism for these photo-switching

processes, a common feature of most Fe

II

spin cross-

over systems, is shown in Fig. 1. Green light is used

for the spin allowed excitation

1

A

1

-

1

T

1

. A fast re-

laxation cascading over two successive intersystem

crossing steps,

1

T

1

-

3

T

1

-

5

T

2

, populates the metast-

able

5

T

2

state. Reverse LIESST is achieved by appli-

cation of red light whereby the

5

T

2

state is excited to

the

5

E state with two subsequent intersystem crossing

processes

5

E-

3

T

1

-

1

A

1

. As demonstrated by Hauser

(1991), photo-switching from LS to HS is also pos-

sible via

1

A

1

-

3

T

1

-

5

T

2

. LIESST can be induced in

spin crossover molecules embedded in polymer films

and in KBr pellets, in addition to solid samples. It is

worth noting that LIESST has also been observed for

the conversion of a HS ground state to a metastable

LS state by red light (Poganiuch et al. 1990).

The effect of light on spin crossover systems is be-

ing pursued vigorously and a number of phenomena

have been reported. These include: light-induced ther-

mal hysteresis (LITH), the effect of raising and low-

ering temperature under constant irradiation (Desaix

et al. 1998); light-perturbed thermal hysteresis

(LPTH), whereby the hysteresis associated with an

ST is shifted to either lower or higher temperatures

under irradiation of different wavelengths (Renz et al.

2000); and ligand-driven light-induced spin crossover

(LD-LISC), whereby irradiation effects a cis–trans

isomerization of the ligand, with subsequent ST at the

Fe

II

center as a consequence of a change in field

strength (Boillot et al. 1999).

5. Applications

The existence of hysteresis is a prerequisite for bista-

bility, which in turn offers the potential for technical

applications of ST systems such as thermal switches

and sensors. Furthermore, the drastic color change

generally accompanying an ST is promising for ap-

plications in displays (Kahn and Launay 1988).

The remarkable changes of ST behavior under ap-

plied pressure can be exploited in pressure sensors for

applications where remote sensing of pressure could

be achieved by a color change in a spin crossover

material. The light-induced switching phenomena de-

scribed above also offer much promise. Data storage

using spin crossover materials, although now limited

to low-temperature regions, may eventually play a

role in holographic devices. Orientational experi-

ments on ‘‘transient grids’’ of a HS/LS lattice have

yielded highly promising refractive index results. The

switching rates in the subnanosecond region at am-

bient temperatures may be a promising basis for op-

tical switches. Patents covering these aspects have

been registered.

6. Future Developments

Research on ST compounds has grown enormously

both from a chemical point of view, allowing the

more-or-less controlled synthesis of new materials

with special properties, and regarding physical char-

acterization using powerful techniques. Aspects which

are the focus of many research groups include:

*

synergism (coupling) of magnetic exchange be-

tween metal centers and ST at the metal atom;

and

*

detailed structural characterization of metasta-

ble states; important findings on the lattice para-

meters of a system in a LIESST-generated metastable

state have emerged and detailed structural studies will

allow greater understanding of light-induced phe-

nomena in general.

See also: Photomagnetism of Molecular Systems

Bibliography

Boillot M-L, Chantraine S, Zarembowitch J, Lallemand J-Y,

Prunet J 1999 First ligand-driven, light-induced spin change

1102

Spin Transition Compounds

at room temperature in a transition-metal molecular com-

pound. New J. Chem. 179–83

Decurtins S, Gu

¨

tlich P, Ko

¨

hler C P, Spiering H, Hauser A 1984

Light-induced excited spin state trapping in a transition metal

complex. Chem. Phys. Lett. 105, 1–4

Desaix A, Robeau O, Jeftic J, Haasnoot J G, Boukheddaden K,

Codjovi E, Linares J, Nogues M, Varret F 1998 Light-in-

duced bistability in spin transition solids leading to thermal

and optical hysteresis. Eur. Phys. J. B6, 183–93

Gu

¨

tlich P, Hauser A, Spiering H 1994 Thermal and optical

switching of iron(II) complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.

33, 2024–54

Hauser A 1991 Intersystem crossing in Fe(II) coordination

compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 111, 275–90

Kahn O, Launay J P 1988 Molecular bistabilty: an overview.

Chemtronics 3, 140

Ko

¨

nig E, Madeja K 1966 Unusual magnetic behaviour of

some iron(II)–bis(1,10-phenanthroline) complexes. Chem.

Commun. 61

Ksenofontov V, Spiering H, Schreiner A, Levchenko G, Good-

win H A, Gu

¨

tlich P 1999 The influence of hydrostatic pres-

sure on hysteresis phase transition in spin crossover

compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 60, 393–9

Martin R L, White A H 1968 The nature of the transition

between high-spin and low-spin octahedral complexes of the

transition metals. Trans. Met. Chem. 4, 113

Poganiuch P, Decurtins S, Gu

¨

tlich P 1990 Thermal- and light-

induced spin transition in [Fe(mtz)

6

][BF

4

]

2

. First successful

formation of a metastable low-spin state by irradiation with

light at low temperatures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 3270–8

Renz F, Spiering H, Goodwin H A, Gu

¨

tlich P 2000 Light per-

turbed hysteresis in an iron(II) crossover compound observed

by the Mo

¨

ssbauer effect. Hyperfine Int. in press

Spiering H, Willenbacher N J 1989 Elastic interaction of high-

spin and low-spin complex molecules in spin crossover com-

pounds. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1, 10089–105

P. Gu

¨

tlich

Johannes Gutenberg Universita

¨

t, Mainz, Germany

H. A. Goodwin

University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Spintronics in Semiconductor

Nanostructures

Spintronics is a relatively new field of electronics

which has been rapidly developing over the past few

years. In order to understand the potential of this

new kind of electronics, it is useful to consider the

basic properties of the electron. One of these prop-

erties is the charge, which has been exploited up to

now in conventional semiconductor electronics. The

charge of a single electron is constant and local

changes of charge can only happen via a current.

However, the electron also has a second property,

namely the spin. The spin can be seen as an angular

momentum which—corresponding to a rotating

charge—also induces a magnetic moment. Much in

contrast to a macroscopic angular momentum the

spin can only have two different (opposite) directions.

It is quantized, with the axis of quantization given by

an external magnetic field. So, whereas the electron

charge has a constant value, the spin of an electron

can have two different values called spin-up and spin-

down which can be ‘‘flipped’’ from one value to the

other. This property allows for the local creation of a

spin population without a current (in contrast to a

charge) but it also means that a spin population can

vanish over time, while a charge population in the

absence of a current cannot.

A well-known effect based on spin is ferromagnet-

ism. In normal materials the spin of the electrons is

distributed statistically. This means that 50% of the

electrons have spin-up and 50% have spin-down. In

ferromagnetic materials such as Fe, Co, or Ni, it is

energetically favorable for a majority of the elec-

trons to have the same spin direction. In this case the

material exhibits a macroscopic magnetic moment

and produces an external magnetic field. Until the

mid-1980s, access to the magnetic properties was

possible only via the magnetic field, using inductive

pickup coils like in tape storage or computer disk

applications.

In 1987 the situation changed, when a new effect

was discovered. Baibich et al. (1988), Binasch et al.

(1989), and Valet and Fert (1993) discovered that

metallic multilayers (see Multilayers: Interlayer Cou-

pling) composed of magnetic and nonmagnetic metals

can exhibit a so-called giant magnetoresistance (see

Giant Magnetoresistance). When an external magnetic

field is applied to the system, the resistance of the

layers decreases. It was soon thereafter determined

that the effect was based on the spin polarization of

the carriers. The spin polarization of the carriers in a

material b is a macroscopic quantity giving the aver-

age spin population of the electronic system:

b ¼

n

m

n

k

n

m

þ n

k

ð1Þ

where n

m

and n

k

are the number of carriers with

spin-up and spin-down, respectively. It is clearly

visible that for a nonmagnetic material b is 0. In a

conventional ferromagnetic material, its value can be

up to 40%.

If we assume the same mobility for spin-up and

spin-down electrons, without loss of generality, we

can assume

b ¼

r

m

r

k

r

m

þ r

k

ð2Þ

where r is the local conductivity.

In a homogeneous material this spin polarization

can give rise to a spin-polarized current. As long as

spin flips are neglected, we can derive two equations

1103

Spintronics in Semiconductor Nanostructures

for the spin-up and spin-down current, respectively:

~

j

mk

¼

~

Er

mk

ð3Þ

The spin polarization of the currents a is then de-

fined as

a ¼

j

m

j

k

j

m

þ j

k

ð4Þ

This corresponds to a picture in which two spin

channels exist, which can be seen as fully spin-polar-

ized noninteracting resistors. However, it is clear that

the voltage applied to both resistors is always the

same, because the interaction of electrons with an

electric field is independent from spin, and current

contacts are typically not spin selective. A spin-po-

larized current can thus only be obtained in a mate-

rial where the carriers are already spin polarized.

The picture changes dramatically, when hybrid

structures consisting of both spin-polarized and un-

polarized materials are investigated. In this case, the

continuity of the respective spin currents has to be

maintained, unless a strong spin scattering is present.

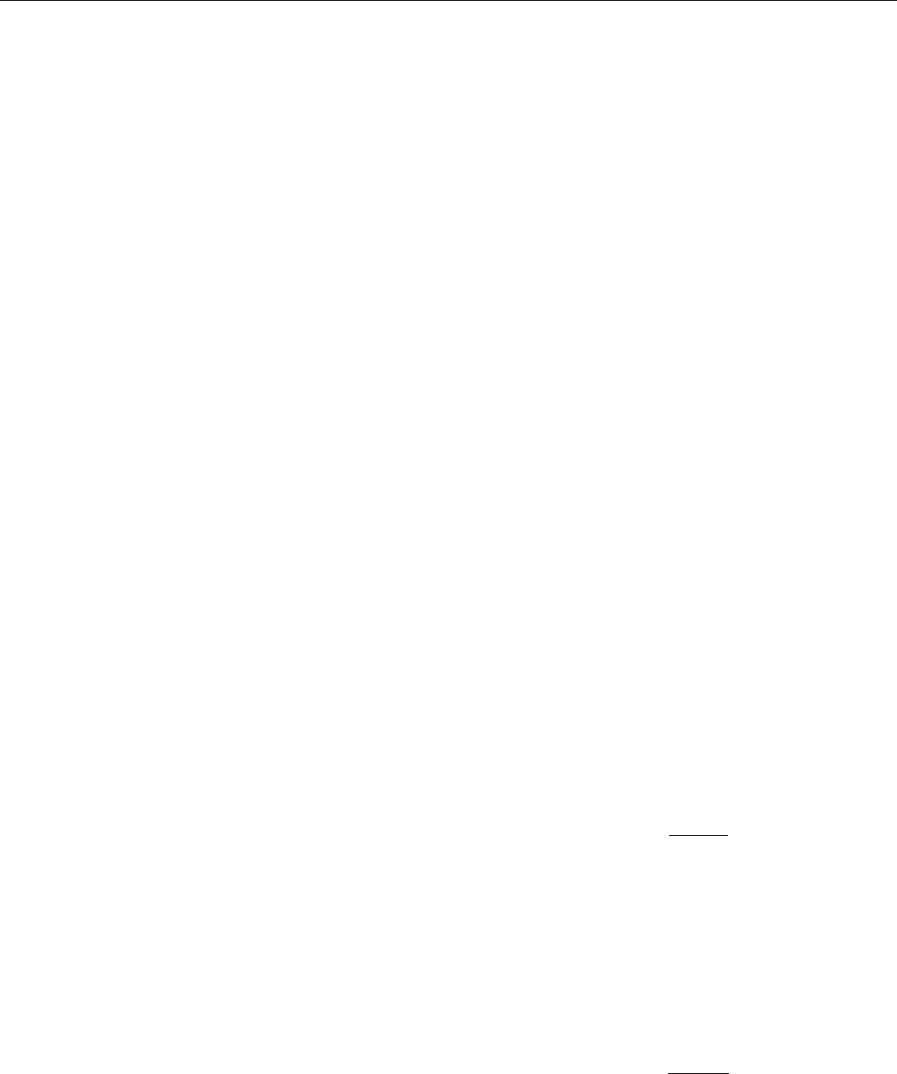

For a ferromagnet/nonmagnet/ferromagnet (FM/

NM/FM) trilayer system this leads to the so-called

two-current model, in which two spin channels are

present. Each channel consists of three resistors, two

for the two ferromagnets and one for the nonmag-

netic material (Fig. 1). When the two magnetic layers

are magnetized in parallel, the two spin channels have

a different total resistance. When the alignment is

antiparallel, the resistances of the spin channels are

equal. Calculating the total resistance of the system

yields different values for parallel and antiparallel

alignment. The value for the parallel alignment is

always lower than for the antiparallel alignment.

This effect is termed giant magnetoresistance (GMR).

Besides the appearance of a magnetoresistance, a

second effect is also present; in the antiparallel state,

the current through both spin channels is equal.

However, in the parallel state, the two spin currents

are different yielding a spin-polarized current in the

nonmagnetic material.

The spin polarization of the current in the parallel

state is equal to

a ¼ b

R

fm

R

sc

2

2ðR

fm

=R

sc

Þþð1 b

2

Þ

ð5Þ

and the normalized difference in resistance between

the parallel and the antiparallel state is

a ¼

b

2

1 b

2

R

2

fm

R

2

sc

2

4ðR

2

fm

=R

2

sc

Þþ2ðR

fm

=R

sc

Þþð1 b

2

Þ

ð6Þ

GMR quickly made its way into applications like

hard-disk read heads and field sensors (see Magnetic

Recording Systems: Spin Valves) and also seemed

desirable for integrating spin-based devices into con-

ventional electronics.

However, in metal-based devices high values for

GMR can only be achieved when the thickness of the

nonmagnetic material is only a few A

˚

, a fact which

limits the device resistance to fractions of an O and is

incompatible with existing CMOS technology. Fur-

thermore, these small dimensions leave no room for

the manipulation of the spin. Indeed in 1990 a new

concept for a semiconductor device for spin manip-

ulation was published by Datta and Das in which a

spin-polarized current through a semiconductor can

be modulated by an electrostatic gate via the spin-

orbit coupling. This device has come to be known as

Figure 1

Resistor model (two-current model) for the

semiconductor device with two ferromagnetic contacts

(up), showing the configuration of the parallel and of the

antiparallel magnetization of the contacts. The depicted

size of the resistors indicates the higher and lower

resistance of spin-up and spin-down channel,

respectively. A straightforward calculation shows that

the total resistance in the parallel configuration is lower

than in the antiparallel case.

1104

Spintronics in Semiconductor Nanostructures

the Datta-transistor (Datta and Das 1990). The au-

thors claimed that the spin-polarized current should

be obtained by using a GMR-like geometry with

ferromagnetic metal contacts on a semiconductor

mesa. Furthermore, optical experiments indicated

that extremely long spin lifetimes and large spin-flip

lengths can be obtained in semiconductors (Kikkawa

and Awschalom 1999). Motivated by these results

several research groups for more than half a decade

tried to achieve the injection of a spin-polarized cur-

rent (spin injection) into a semiconductor, however,

without any results that could not be interpreted as

side effects like magnetoresistance or Hall effect

(Monzon and Roukes 1999).

The explanation for this failure is simple. If we

replace the nonmagnetic metal in the GMR config-

uration (Fig. 1) by a semiconductor, it seems on first

sight that the picture does not change. However, us-

ing real numbers for the resistance values shows that

in comparison to the resistance of the semiconductor,

the resistance of the ferromagnet can be neglected.

Even when the spin polarization of the ferromagnet is

80% or 90%, the difference in resistance of both spin

channels will be too low to induce any difference in

the current of the two spin channels, and any current

through the semiconductor remains unpolarized.

In Eqn. (5) this corresponds to R

fm

{R

sc

. This

problem was first discussed in Schmidt et al. (2000)

where the calculation was extended to a local de-

scription, in which spin flips in the ferromagnetic

material are taken into account. In this case, the out-

come is similar, only the resistance R

fm

is replaced by

l

fm

=s

fm

which is the resistance of a sheet of the

ferromagnet with the thickness of the spin-flip length.

The spin polarization of the current in the semicon-

ductor is thus proportional to the spin polarization of

the ferromagnet b; however, it is reduced by a factor

of ðl

fm

=s

fm

Þ=ðx

0

=s

sc

Þ where x

0

and s

sc

are the length

and conductivity of the semiconductor, respectively.

It seems obvious that one way to circumvent this

conductance mismatch is to increase the value of

l

fm

=s

fm

; however, ferromagnetic materials typically

have a small spin-flip length and an extremely high

resistivity would be needed, which will deteriorate the

electrical properties of a device. One way to achieve

such a high resistance contact has been discussed by

Rashba (2000) and by Fert et al. (2001). Less obvious

is the use of fully spin-polarized materials (see Half-

metallic Magnetism) with b ¼1. In this limit we ob-

tain a ¼1 independent from the resistivity and the

spin-flip length in the materials. This is possible be-

cause one of the spin channels is now completely

blocked due to the absence of carriers.

Approximately at the same time as the conduct-

ance mismatch was identified, new experiments based

on a different class of magnetic materials were

published. When semiconductors are doped with

magnetic ions (e.g., Mn or Fe), they can become

ferromagnetic or strongly paramagnetic (see Dilute

Magnetic Semiconductors). ZnMnSe is an example of

these so-called dilute magnetic semiconductors

(DMSs). Without external magnetic fields, the Mn-

spins are not aligned or are antiferromagnetically

coupled. However, at low temperatures and in an

external magnetic field the material exhibits a giant

Zeeman splitting. The g-factor can be larger than 100,

leading to a splitting of the conduction band of up to

20 meV. At low temperatures, where kT is smaller

than the Zeeman splitting, the population of the two

spin levels can be expressed by a Boltzmann factor.

The upper spin level is thus completely depopulated

and the material should act as a perfect spin aligning

contact.

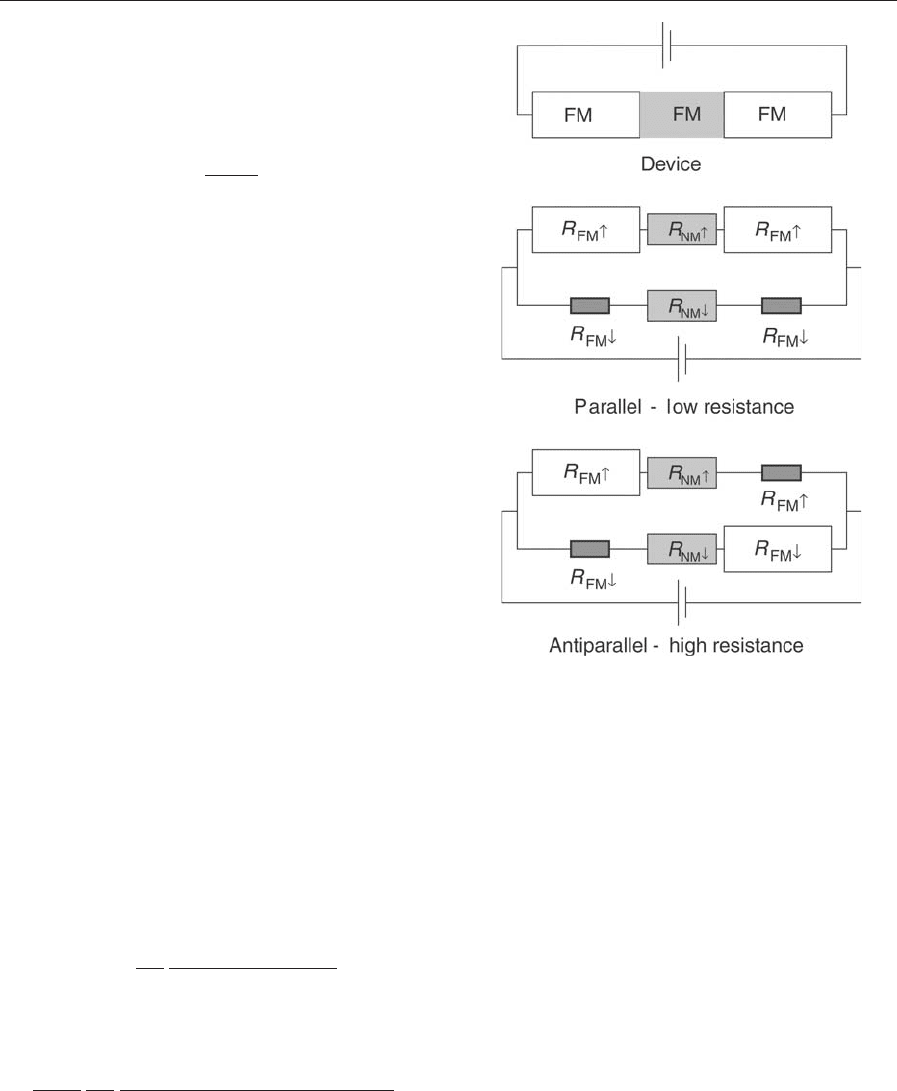

The first proof of high-efficiency spin injection us-

ing dilute magnetic semiconductors was obtained in

1999 using a light emitting diode (LED) fitted with a

DMS contact. When an electron and a hole recom-

bine in GaAs and emit a photon, the polarization of

this photon is related to the spins of the hole and the

electron via the quantum mechanical selection rules.

When unpolarized holes recombine with spin-polar-

ized electrons, there are two possibilities. In case light

and heavy holes are degenerate, the circular optical

polarization of the emitted photons is

P

opt

circ

¼

s

þ

s

s

þ

þ s

¼

ð3n

m

þ n

k

Þð3n

k

þ n

m

Þ

ð3n

m

þ n

k

Þþð3n

k

þ n

m

Þ

¼

1

2

n

m

n

k

n

m

þ n

k

¼

1

2

a ð7Þ

When the degeneracy is lifted the circular optical

polarization is equal to the electron spin polarization.

A GaAs LED which is fed with unpolarized holes

from the p-side and with spin-polarized electrons

from the n-side will thus emit light with a circular

polarization which is directly proportional to the

electron spin polarization. Such a diode was fabri-

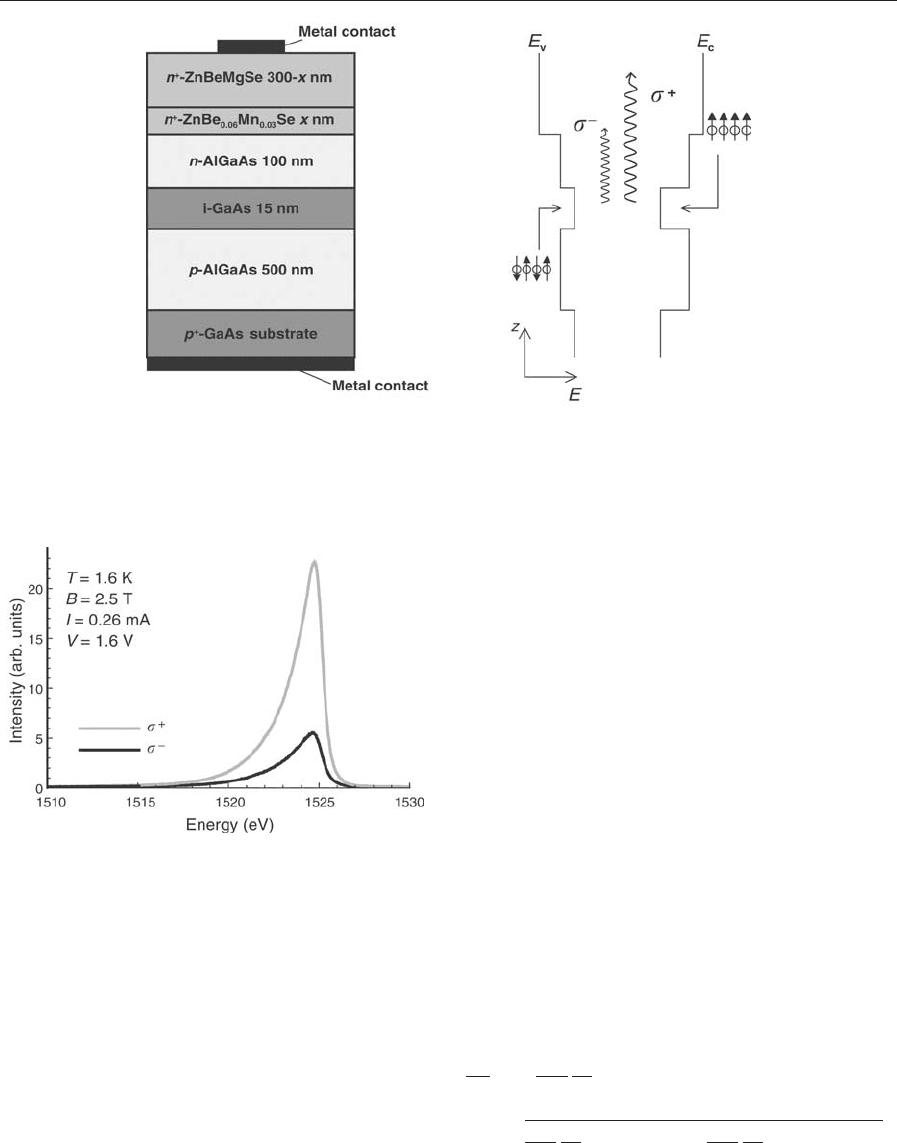

cated (Fig. 2) and characterized at low temperature

and in moderate magnetic fields between 0 T and 5 T.

The hole confinement in the diode was weak in order

to insure degenerate hole states. Figure 3 shows a

typical electroluminescence (EL) spectrum of a spin

LED. The maximum polarization obtained in the

experiment was up to 46% indicating an electron spin

polarization of more than 90% (Fiederling et al.

1999). A similar experiment was performed using

ferromagnetic GaMnAs, however, with a strongly

reduced efficiency (Ohno et al. 1999).

When DMSs are used as spin aligners however,

electrical detection of spin-polarized transport is

more difficult than for ferromagnets. The paramag-

netic behavior makes it virtually impossible to

achieve two small contacts with antiparallel magnet-

ization and thus excludes GMR-like experiments. In

addition, the magnitude of magnetoresistance effects

due to spin injection is typically proportional to the

square of the spin injection efficiency (Eqn. (6)).

1105

Spintronics in Semiconductor Nanostructures

While the latter would not present too big a problem

due to the high spin injection efficiency demonstrated

in the optical experiment, the realization of GMR

could only be achieved using very small contacts with

small ferromagnetic bias magnets that are difficult to

realize.

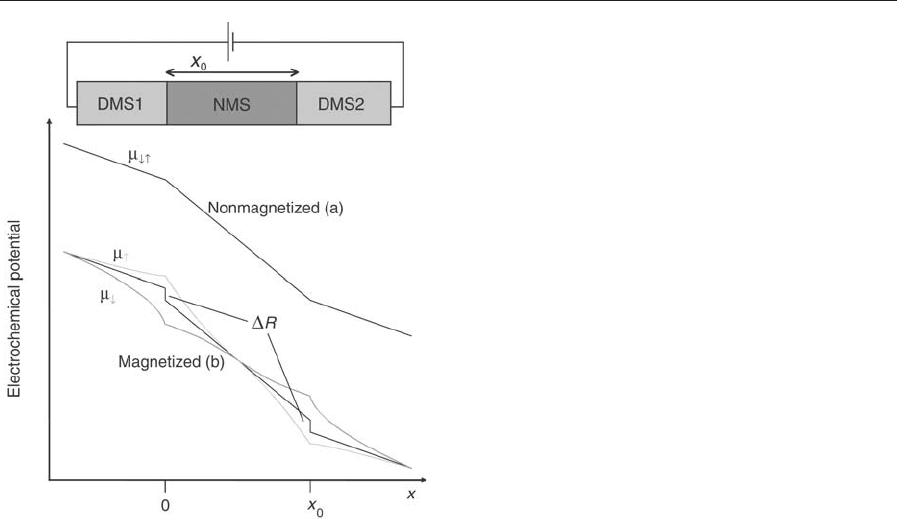

However, the splitting of the electrochemical

potentials which is always present in spin injection

experiments can be used in electrical detection of

the spin injection effect. When a nonmagnetic semi-

conductor is fitted with two dilute magnetic semi-

conductor contacts and a voltage is applied, a new

magnetoresistance effect can be observed. While the

DMS is not magnetized, current through the sample

will lead to an identical slope for the electrochemical

potentials of spin-up and spin-down electrons in the

nonmagnetic semiconductor (NMS) (Fig. 4(a)). As

soon as the DMS is magnetized, the electrochemical

potentials will split at the interfaces leading to a kind

of boundary resistance (Fig. 4(b)).

Much in contrast to giant magnetoresistance, this

boundary resistance persists even if the spacing be-

tween the contacts is larger than the spin-flip length

in the NMS (the effect can also be present in a single

contact geometry). This boundary resistance will ap-

pear as a magnetoresistance, which can be up to

100% of the resistance of the NMS. The increase of

the resistance can be attributed to the nonequilibrium

distribution of spin currents in the spin channels of

the NMS. At the boundary, one spin channel is sup-

pressed over the range of the spin-flip length, reduc-

ing the total conductivity. In the ideal case of full spin

polarization and no spin scattering, one spin channel

is completely suppressed throughout the NMS lead-

ing to a reduction of the conductivity by a factor of 2.

For a finite spacing of the contacts, the magnetore-

sistance can be shown to be

DR

R

sc

¼ b

2

l

dms

s

dms

s

sc

x

0

2

l

dms

s

dms

s

sc

l

sc

ð1 þ e

x

0

=l

sc

Þþ2

l

dms

s

dms

s

sc

x

0

e

x

0

=l

sc

þ 1 b

2

ð8Þ

Figure 2

Layer sequence (left) and band structure (right) of the spin aligner LED. The device consists of a GaAs/AlGaAs LED

which has a spin aligning n-contact. The electrons are aligned in the II–VI-layer and recombine in the GaAs with

unpolarized holes coming from the GaAs substrate.

Figure 3

EL spectrum of a typical spin LED. The signal is

strongly polarized.

1106

Spintronics in Semiconductor Nanostructures

The effect has been observed experimentally in an

all II–VI semiconductor structure where the NMS

was ZnBeSe and the DMS was ZnBeMnSe. The ob-

served effect was up to 25% of the total device re-

sistance (Schmidt et al. 2001). The deviation from

100% can be explained by the fact that the contact

spacing in this experiment was much larger than the

expected spin scattering length in ZnBeSe.

Meanwhile, different experiments using optical de-

tection and based on ferromagnetic metal contacts

with tunnel barriers have been published (Motsnyi

et al. 2002, Zhu et al. 2001). Although the efficiency

obtained is not as high as in the case of DMS con-

tacts, they show that based on a detailed understand-

ing of the phenomena, novel approaches can lead

towards room-temperature applications. In addition,

over the past years a large research effort has been

initiated and is ongoing which is dedicated to highly

spin-polarized materials that are ferromagnetic at

room temperature. These could replace DMSs and

still maintain the same spin injection efficiency that is

needed for device applications.

Bibliography

Baibich M N, Broto J M, Fert A 1988 Giant magnetoresistance

of (001)Fe/(001)Cr magnetic superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett.

61, 2472

Binasch G, Gru

¨

nberg P, Saurenbach F, Zinn W 1989 Enhanced

magnetoresistance in layered structures with antiferromag-

netic interlayer exchange. Phys. Rev. B 39, 4828

Datta S, Das B 1990 Electronic analog of the electrooptic

modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 56 (7), 665

Fert A, Jaffres H 2001 Conditions for efficient spin injection

from a ferromagnetic metal into a semiconductor. Phys. Rev.

B 64, 184420

Fiederling R, Keim M, Reuscher G, Ossau W, Schmidt G,

Waag A, Molenkamp L W 1999 Injection and detection of a

spin-polarized current in a light-emitting diode. Nature

(London) 402, 787

Kikkawa J M, Awschalom D D 1999 Lateral drag of spin co-

herence in gallium arsenide. Nature 397, 139–41

Monzon F G, Roukes M L 1999 Spin injection and the local

Hall effect in InAs quantum wells. JMMM 198–199, 632

Motsnyi V F, De Boeck J, Das J, Van Roy W, Borghs G,

Goovaerts E, Safarov V I 2002 Electrical spin injection in a

ferromagnet/tunnel barrier/semiconductor heterostructure.

Appl. Phys. Lett. 81 (2), 265

Ohno Y, Young D K, Beschoten B, Matsukura F, Ohno H,

Awschalom D D 1999 Electrical spin injection in a ferro-

magnetic semiconductor heterostructure. Nature 402, 790

Rashba E I 2000 Theory of electrical spin injection: tunnel

contacts as a solution of the conductivity mismatch problem.

Phys. Rev. B 62, R16267

Schmidt G, Ferrand D, Molenkamp L W, Filip A T, van Wees

B J 2000 Fundamental obstacle for electrical spin injection

from a ferromagnetic metal into a diffusive semiconductor.

Phys. Rev. B 62, R4790

Schmidt G, Richter G, Grabs P, Gould C, Ferrand D, Mole-

nkamp L W 2001 Large magnetoresistance effect due to spin

injection into a nonmagnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett.

87, 227203

Valet T, Fert A 1993 Theory of the perpendicular magnetore-

sistance in magnetic multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 48 (10), 7099

Zhu H J, Ramsteiner M, Kostial H, Wassermeier M, Schonherr

H P, Ploog K H 2001 Room-temperature spin injection from

Fe into GaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87 (1), 016601

G. Schmidt

Universita

¨

tWu

¨

rzburg, Germany

SQUIDs: Amplifiers

Radio-frequency (RF) amplifiers virtually always

involve semiconductors as active elements. Noise

temperatures of about 2 K can be achieved with these

devices at frequencies of several hundred megahertz

(Bradley 1999), when the amplifier is cooled to liquid

helium temperatures. Cooling the amplifier to still

lower temperatures does not reduce the noise tem-

perature further because of intrinsic noise sources in

Figure 4

Schematic drawing of the device with two DMS contacts

and plot of the electrochemical potentials for the two

spin channels. Without applied magnetic field (a) the

potentials are identical. As soon as a magnetic field is

applied (b) the potentials split at the interfaces.

1107

SQUIDs: Amplifiers

the transistor. It is also questionable whether a

transistor can be cooled to, say, 1 K because of the

relatively large power dissipation.

At least at frequencies of several hundred mega-

hertz, better results can be obtained by using a

d.c. superconducting quantum interference device

(SQUID) as an RF amplifier. For this device, the

noise temperature continues to decrease linearly with

the bath temperature as it is lowered to about 0.1 K

(Wellstood et al. 1994). This is because the power

dissipation in the SQUID is orders of magnitude

lower than for a transistor, and because the only in-

trinsic noise source at frequencies above a few hertz is

Nyquist noise in the shunts of the junctions.

1. Conventional d.c. SQUID Amplifier

The conventional d.c. SQUID amplifier (Hilbert and

Clarke 1985) consists of two resistively shunted Jose-

phson junctions (see Josephson Junctions: Low-T

c

,

Josephson Junctions: High-T

c

) incorporated into a

square washer of inductance L over which is depos-

ited a superconducting input coil of n turns with in-

ductance L

i

En

2

L. The SQUID is current and flux

biased so that the flux to voltage transfer function,

V

F

¼@V/@F, is close to a maximum. A signal current

I

i

in the input coil generates a flux M

i

I

i

in the SQUID

and an output voltage V

0

EM

i

I

i

V

F

across it, where

M

i

is the mutual inductance between the input coil

and the SQUID. With sufficiently large M

i

and V

F

,a

relatively high gain can be obtained in this configu-

ration. The conventional flux locked loop operation

of the SQUID, which is used to linearize its transfer

function, cannot be realized for the required high-

frequency operation. This means that the amplitude

of the input signal is limited to currents that produce

flux changes in the SQUID of less than about F

0

/4.

Fortunately, in most high-frequency applications the

input signal amplitude is much less than that. If

a SQUID with a flux noise of 10

6

F

0

Hz

1/2

is

used one can still achieve a dynamic range of nearly

120 dBHz

1/2

. Larger flux changes, caused, for ex-

ample, by 50 Hz or 60 Hz fields, can easily be com-

pensated by operating the SQUID in a slow flux

locked loop, which maintains the flux bias at odd

multiples of F

0

/4.

Using a SQUID amplifier with an input circuit

tuned to 93 MHz, Hilbert and Clarke (1985) achieved

a gain of about 18 dB and a noise temperature of

about 1.5 K for a bath temperature of 4.2 K. Above

100 MHz, however, parasitic capacitance, C

p

, be-

tween the input coil of inductance L

i

and the SQUID

produces self-resonances and severely reduces the

gain. The L

i

C

p

parallel resonance can be moved to

higher frequencies by reducing the number of turns,

reducing their width, or increasing the thickness of

the insulating layer that separates the coil from the

SQUID. However, reducing the number of turns may

reduce the mutual inductance between the coil and

the SQUID to a value that is too small to produce a

satisfactory gain. For the same reason the size of the

SQUID hole should be made as large as possible

(e.g., 200 mm 200 mm).

Takami et al. (1989) have described a SQUID am-

plifier in which the input circuit is tuned to the desired

resonant frequency by adjusting the thickness of the

insulating layer between the SQUID and coil, thus

varying the parasitic capacitance. To match the high

resistance of the parallel L

i

C

p

circuit to the 50 O signal

source, the signal is coupled to the coil by a small

(3 pF) capacitor. This scheme leads to a relatively high

quality factor, Q,oftheL

i

C

p

circuit, a high input cur-

rent at the resonant frequency, and thus a high gain.

Gains have been measured of up to 23 dB at 150 MHz,

and a noise temperature of about 0.7 K for a bath

temperature of 4.2 K. Unfortunately, the high Q of the

resonant circuit decreases the bandwidth to about 1%

of the operating frequency, which for many applica-

tions is too small. Increasing the bandwidth by de-

creasing Q decreases the gain. Nevertheless, for

narrow-band applications such as NMR, this coupling

scheme provides a high gain, low noise amplifier for

frequencies of up to a few hundred megahertz.

If operation at higher frequencies is required, the

parasitic capacitance either has to be reduced or

its influence removed with a resonance technique.

Reducing the capacitance can be achieved by placing

the input coil inside the SQUID hole. Because of the

decreased coupling between coil and SQUID, how-

ever, the gain is quite small. Tarasov et al. (1995)

have made a SQUID amplifier in this way, and

reported gains of 8 dB at 700 MHz and a noise tem-

perature of about 1.5 K. In an alternative design,

Prokopenko et al. (1999) used a SQUID amplifier

with a series resonant input circuit to achieve a gain

of 10 dB at 3.8 GHz and a noise temperature of 5 K.

2. SQUID Amplifier with Microstrip Input

Coupling

An alternative way of achieving high gains and low

noise temperatures at high frequencies is to take ad-

vantage of the parasitic capacitance, by operating the

input coil of a d.c. SQUID as a microstrip resonator.

The input signal is no longer coupled to the two ends

of the input coil, but rather between one end of the

coil and the SQUID loop, which acts as a ground

plane for the coil; the other end of the coil is left

open. The microstrip resonator is thus formed by the

inductance of the input coil and its ground plane and

the capacitance between them. In this configuration,

the parasitic capacitance no longer prevents currents

from flowing through the coil.

For the case in which the impedance, Z

s

, of the

source coupled to one end of the microstrip is larger

than its characteristic impedance, Z

0

, and the other

1108

SQUIDs: Amplifiers

end of the input coil is left open, the fundamental

resonance occurs when the length, l, of the microstrip

is equal to half the wavelength of the RF signal. In

this mode, the microstrip resonator is analogous to a

parallel tuned circuit and, neglecting losses in the

microstrip and the SQUID, one calculates a quality

factor Q ¼pZ

s

/2Z

0

. At the resonant frequency the

current fed into the resonator is amplified by Q, pro-

ducing a magnetic flux that is coupled into the

SQUID via a mutual inductance M

s

¼a(LL

s

)

1/2

,

where L

s

is the microstrip inductance and a the cou-

pling coefficient. One selects the resonant frequency

by appropriate choice of the length of the coil. Q,

which determines the bandwidth of the amplifier, can

be varied by selecting the characteristic impedance of

the microstrip; i.e., by choosing an appropriate width

of the turns of the coil and thickness and dielectric

constant of the insulating layer between the coil and

SQUID. One has to keep in mind, however, that re-

ducing Q will increase the bandwidth and lower the

gain, since the resonant current amplification is pro-

portional to Q.

Since the conventional washer SQUID is an asym-

metric device (the two Josephson junctions are situ-

ated close together rather than on opposite sides of

the SQUID loop), one can either ground the washer

or ground the counter electrode close to the Joseph-

son junctions. Using the washer as ground plane for

the input coil suggests one should ground the washer.

However, it is also possible to ground the counter

electrode and have the washer at output potential. In

this case, depending on the sign of V

F

(which deter-

mines the phase shift between input and output of the

amplifier), one can obtain either a negative or positive

feedback from the output to the input, and using

positive feedback, the gain of such amplifiers can be

enhanced substantially.

Using this configuration, Mu

¨

ck et al. (1998) meas-

ured gains of 20 dB up to a frequency of 1.3 GHz.

Noise temperatures as low as 100 mK (at 400 MHz)

have been measured when the SQUID is cooled to

0.4 K (Andre

´

et al. 1999). This noise temperature is

only about a factor of three above the quantum limit.

The intrinsic noise temperature of the amplifier is typ-

ically 1/4 of the bath temperature, T,and,within

measurement errors, scales with T.

The microstrip amplifier can be tuned by means of

a varactor diode, which is connected to the open end

of the microstrip. Changing the capacitance of the

varactor diode by an applied d.c. voltage enables one

to reduce the resonant frequency of the amplifier by

nearly a factor of two. If gains higher than 20 dB are

desired, two amplifiers can be connected in cascade.

3. Conclusion

For applications requiring extremely low noise tem-

peratures at frequencies of several hundred megahertz

and above, an RF amplifier based on a d.c. SQUID is

a promising alternative to semiconductor amplifiers.

Such applications include intermediate frequency am-

plifiers for superconductor–insulator–superconductor

(SIS) mixers, NMR, or Axion detectors. Gains of

more than 20 dB at frequencies exceeding 1 GHz have

been obtained with such amplifiers and noise temper-

atures as low as 100 mK. An exciting possibility is the

expectation that the quantum limit could be reached

with a d.c. SQUID amplifier cooled to about 100 mK.

A challenge for future work is the extension to higher

frequencies. It should be possible to operate a SQUID

amplifier at frequencies exceeding 10 GHz, probably

by modifying the geometry of the SQUID from the

square washer format to, perhaps, an in-line config-

uration. One may hope that the design and testing of

such SQUID amplifiers will be undertaken in the not-

too-distant future.

See also: SQUIDs: The Instrument

Bibliography

Andre

´

M -O, Mu

¨

ck M, Clarke J, Gail J, Heiden C 1999 Mi-

crostrip d.c. SQUID radio frequency amplifier with tenth-

kelvin noise temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 698–700

Bradley R F 1999 Cryogenic, low noise, balanced amplifiers for

the 300–1200 MHz band using heterostructure field-effect

transistors. Nucl. Phys. B (Proc. Suppl.) 72,137–44

Hilbert C, Clarke J 1985 DC SQUIDs as radio frequency am-

plifiers. J. Low Temp. Phys. 61, 263–80

Mu

¨

ck M, Andre

´

M -O, Clarke J, Gail J, Heiden C 1998 Radio

frequency amplifier based on a niobium d.c. SQUID with

microstrip input coupling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 2885–7

Prokopenko G V, Balashov D M, Shitov S V, Koshelets V P,

Mygind J 1999 Two-stage S-band d.c. SQUID amplifier.

IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. AS-9, in press

Takami T, Noguchi T, Hamanaka H 1989 A d.c. SQUID r.f.

amplifier. IEEE Trans. Mag MAG-25, 1030–3

Tarasov M A, Prokopenko G V, Koshelets V P, Lapitskaya I L,

Filippenko L V 1995 Integrated r.f. amplifier based on d.c.

SQUID. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. AS-5, 3226–9

Wellstood F C, Urbina C, Clarke J 1994 Hot-electron effects in

metals. Phys. Rev. B 49, 5942–55

M. Mu

¨

ck

Institut fu

¨

r Angewandte Physik der Justus-Liebig-

Universita

¨

t Giessen, Germany

SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications

A major application of SQUID systems (see

SQUIDs: The Instrument) is in biomagnetism, a dis-

cipline where the faint magnetic fields associated with

electrophysiological functions of the heart, brain,

nerves, or muscles are detected with the ultrahigh

field sensitivity of SQUIDs. Biomedical investigations

1109

SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications