Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

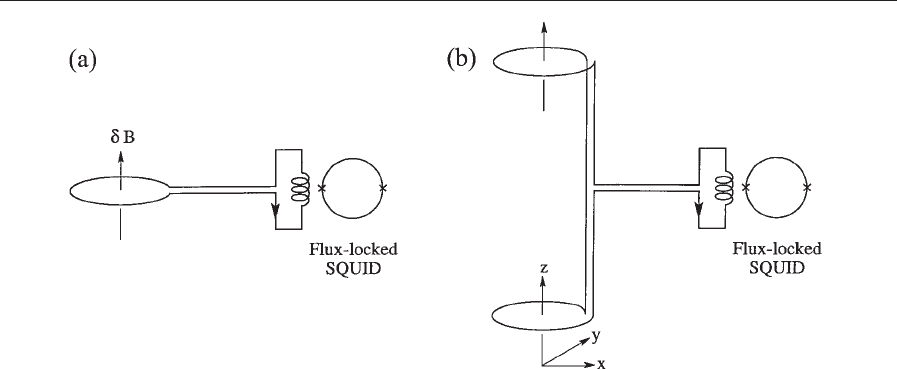

of its pickup loops—while leaving signals at a dis-

tance less than its baseline largely unattenuated.

Second-derivative axial gradiometers are also used,

as are thin-film planar gradiometers measuring off-

diagonal gradients.

3. Low-T

c

SQUIDs as High-frequency Amplifiers

Low-T

c

SQUIDs can be operated at frequencies up to

about 100 MHz (see SQUIDs: Amplifiers), and have

been used as sensitive detectors of NMR and nuclear

quadrupole resonance. In this application, the

SQUID is operated open loop, with the static flux

adjusted to optimize V

F

. At 100 MHz gains of about

20 dB and noise temperatures of about 1 K have been

achieved (Hilbert and Clarke 1985).

A subsequent configuration—the so-called ‘‘micro-

strip SQUID amplifier’’—has been realized to am-

plify signals up to about 1 GHz (Mu

¨

ck et al. 1998). In

this device the signal is coupled between one end of

the spiral input coil and the SQUID washer (Fig. 2),

which form a microstrip. When the signal frequency

corresponds to the half-wavelength resonance in the

microstrip, gains of up to 25 dB have been achieved.

Cooled to 20 mK, such amplifiers have noise temper-

atures close to the quantum limit.

4. High-T

c

d.c. SQUIDs

Most high-T

c

SQUIDs (Koelle et al. 1999) are in-

tended for operation at 77 K. The constraint F

2

0

/

2L\40k

B

T imposes an upper limit on L of about 50

pH; at this value the constraint b

L

E1 implies

I

0

E20 mA. All practical high-T

c

d.c. SQUIDs are

fabricated from thin films of YBCO, deposited by

laser ablation, sputtering, or co-evaporation. The

major remaining difficulty in the fabrication of these

devices is the lack of a reproducible junction tech-

nology that produces acceptable parameters at 77 K.

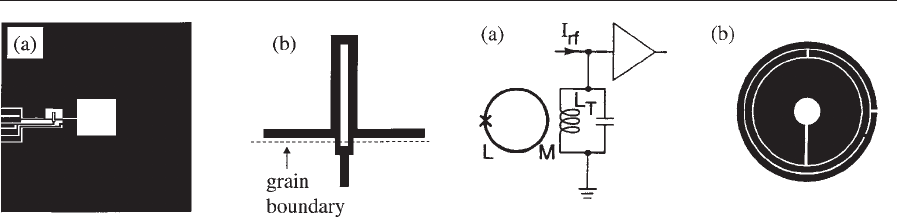

The most commonly used junctions involve grain

boundaries, formed by the epitaxial growth of the

film either on bicrystal substrates or over a step pat-

terned in the substrate, which is usually SrTiO

3

. The

film crossing the grain boundary is patterned to a

width of 1–2 mm. Although the results are generally

satisfactory, the yield of junctions with acceptable

parameters is smaller than is desirable. These junc-

tions do have the virtue of simplicity in that the entire

SQUID is patterned in a single layer of YBCO, most

usually by ion milling. A dozen or so devices with

500 mm 500 mm washers can be patterned on a

10 mm 10 mm substrate.

Compared with their low-T

c

counterparts, high-T

c

grain boundary junctions produce high levels of 1/f

noise. Fortunately, this noise can be greatly reduced

in the d.c. SQUID by a scheme in which the bias

current is reversed, typically at a few kilohertz. The

noise of high-T

c

SQUIDs varies more widely than

that of low-T

c

SQUIDs, reflecting the variability in

the junction parameters. The best devices achieve a

flux noise of about 5 mF

0

Hz

1/2

at frequencies down

to about 1 Hz, corresponding to a noise energy of

10

30

JHz

1

, or a little better. For reasons that re-

main unclear, noise energies are typically an order of

magnitude higher than the computed values. Since

the flux-locked loop is similar to that used for low-T

c

devices, with the addition of bias reversal, compara-

ble values of dynamic range, frequency response, and

slew rate are achieved.

The small area of high-T

c

SQUIDs mandates the

use of a flux transformer for sensitive magnetometers.

One approach is to use a configuration much like that

of Fig. 2. Although integrated devices of this kind

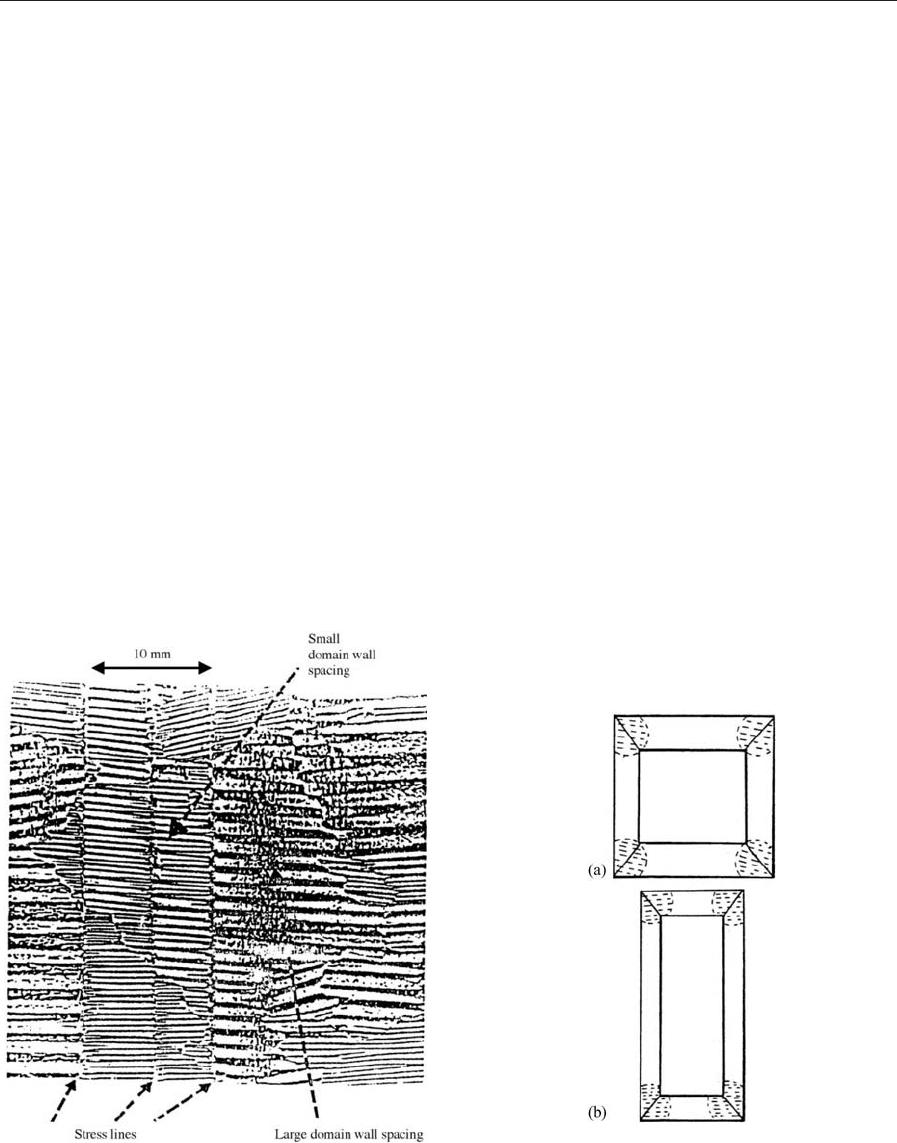

Figure 4

Wire-wound superconducting flux transformers: (a) magnetometer; (b) first-derivative axial gradiometer.

1120

SQUIDs: The Instrument

have been successfully fabricated, the difficulty of

obtaining appropriate junction parameters and a ful-

ly epitaxial YBCO–SrTiO

3

–YBCO multilayer on the

same substrate has led to low yields. As a result,

many groups have resorted to a flip-chip technology

in which the SQUID and flux transformer are made

on separate chips that are pressed together face-to-

face, separated by a thin insulating layer. The best of

these magnetometers achieves a white noise below

10 fT Hz

1/2

; however, all these multilayer structures

exhibit 1/f noise, which increases the noise to, typi-

cally, 30 fT Hz

1/2

at 1 Hz. An alternative approach,

illustrated in Fig. 5, is the so-called ‘‘directly coupled

magnetometer,’’ which has the advantage of being

patterned in a single YBCO layer. A current induced

in the large area pickup loop by a magnetic field is

injected directly into the body of the SQUID. The

magnetic field noise of the best devices, about

30 fT Hz

1/2

, remains constant at frequencies down

to about 1 Hz.

Various configurations of gradiometers have been

fabricated and tested. Given that suitable high-T

c

wire is not available, hardware gradiometers are in-

variably planar structures that measure off-diagonal

gradients. The best of these has a baseline of about

50 mm, and attenuates uniform magnetic fields by

roughly 10

3

. In an alternative approach one subtracts

the signals from high-T

c

magnetometers electronical-

ly to form first or second derivatives.

An important issue with high-T

c

devices is their

operation in an ambient magnetic field, such as that

of the earth. When a high-T

c

film is field cooled, flux

vortices may enter; thermally induced hopping of

these vortices can produce large levels of 1/f noise.

This problem is largely overcome by ensuring that the

film has a narrow linewidth, formed, for example, by

patterning it with holes or slots.

5. High-T

c

RF SQUIDs

The RF SQUID (Fig. 6(a)) consists of a single Joseph-

son junction integrated into a superconducting loop

that is inductively coupled to the inductance, L

T

,of

an LC resonant (tank) circuit. The tank circuit is

driven by a current at frequency o

RF

/2p, and the re-

sultant RF voltage is periodic in the flux applied to

the SQUID with period F

0

. The RF can range from

20 MHz up to 10 GHz. The RF amplitude is demod-

ulated, and this signal is amplified, integrated, and fed

back to flux lock the SQUID as in Fig. 3.

Operation of the RF SQUID relies on the fact that

the applied flux, F, which induces a supercurrent

around the loop, in general differs from the total flux,

F

T

. There are two distinct modes of operation. For

b

0

L

2pLI

0

/F

0

41, the plot of F

T

vs. F is hysteretic.

Energy is dissipated each time an RF cycle traverses a

hysteresis loop; the number of these traversals per

unit time is periodic in F. As a result, the quality

factor of the tank circuit and hence the voltage across

it at constant RF current are also periodic in F.

However, for b

0

L

o1 there is no hysteresis and no

dissipation. Rather, the SQUID behaves as a para-

metric inductance, modulating the effective induct-

ance and hence the resonant frequency of the tank

circuit as the flux is varied. Consequently, at constant

drive frequency the RF voltage is again periodic in F.

In the hysteretic regime, for an optimized RF

SQUID the noise energy is given by (Chesca 1998)

eðf ÞEðLI

2

0

=2o

RF

Þð2pk

B

T=I

0

F

0

Þ

4=3

ð2Þ

Note that e scales inversely with o

RF

, implying that

higher frequency operation results in lower noise. In

the nonhysteretic regime, e also scales as 1/o

RF

up

to the limiting value o

RF

¼R/L, at which frequency,

under optimum conditions (Chesca 1998), one

obtains

eðf ÞE3k

B

T=ðb

0

L

Þ

2

ðR=LÞð3Þ

Equations (2) and (3) show that e(f) increases with

T. For low-T

c

SQUIDs, however, the noise temper-

ature of the amplifier coupled to the tank circuit is

often much higher than the bath temperature so that

Figure 5

(a) Directly coupled magnetometer fabricated from a

thin film of YBCO (not to scale); (b) magnified view of

the d.c. SQUID showing location of the two grain

boundary junctions (courtesy of Hsiao -Mei Cho).

Figure 6

RF SQUID. (a) Schematic showing SQUID inductively

coupled to a resonant circuit excited by an RF current,

I

rf

. (b) Coplanar microwave resonator and flux

concentrator; RF SQUID is on a separate substrate, and

is not shown (Zhang et al. 1998).

1121

SQUIDs: The Instrument

the system noise is much greater than the intrinsic

noise. This is one reason why the d.c. SQUID is pre-

ferred. When the temperature is raised to 77 K the

intrinsic noise of the d.c. SQUID increases, while the

effective system noise temperature of the RF SQUID

changes little. As a result, at 77 K the noise energy of

the RF SQUID, operated at gigahertz frequencies, is

not very different from that of the d.c. SQUID.

The first generation of RF SQUIDs involved thin-

film YBCO washers containing a central hole and a

slit connected by one (or often two) grain boundary

junctions. The washer was inductively coupled to a

tank circuit, excited at frequencies that ranged from

20 MHz to 200 MHz. The magnetic field sensitivity

could be enhanced by means of a flux concentrator,

made from bulk YBCO, or a single-layer flux trans-

former. The most sensitive of these devices achieved a

magnetic field noise below 30 fT Hz

1/2

at frequencies

down to about 1 Hz. However, the large size of these

magnetometers—up to 50 mm across—limited their

applicability. Subsequently, operation at higher fre-

quencies, 1–3 GHz, was achieved by replacing the

lumped tank circuit with a microwave resonator. In

the design shown in Fig. 6(b) the circular RF SQUID

(not shown) is flip-chip coupled to the YBCO reso-

nator, which consists of a flux concentrator sur-

rounded by two coplanar lines (Zhang et al. 1998).

The relative position of the gaps in these lines and of

the connection between them enables one to adjust

the resonant frequency. This configuration is straight-

forward to fabricate, involving the fabrication of a

single-layer RF SQUID on one chip and of a single-

layer resonator on the other. The best white noise

achieved is below 20 fT Hz

1/2

; however, the level of

1/f noise is high, about 100 fT Hz

1/2

at 1 Hz. More

sophisticated devices with a multiturn flux transform-

er integrated with the resonator have also been

developed.

A detailed comparison of the measured and pre-

dicted noise of the RF SQUID has proved difficult,

partly because it is difficult to determine the critical

current accurately so that it is not clear whether b

0

L

is greater or less than unity. It is likely that some

devices are operated in a mixed mode in which

the flux-dependent RF signal is produced by varia-

tions in both dissipation and inductance. RF

SQUIDs have been configured as gradiometers using

both thin-film structures and electronic subtraction of

magnetometers.

6. Final Remarks

The technology of low-T

c

d.c. SQUIDs, based on

Nb–Al

x

O

y

–Nb tunnel junctions, is highly developed,

enabling one to fabricate reproducible devices in

quantity on 2–4 in (5–10 cm) silicon washers. The

sensitivity of these devices as magnetometers, around

1fTHz

1/2

, surpasses the demands of virtually all

applications. Thus, there is little research on low-T

c

d.c. SQUIDs themselves, at least for low-frequency

applications, although there are ongoing efforts to

make the associated electronics less expensive, par-

ticularly for systems with large numbers of channels.

The emphasis is much more on applications, most

notably in biomagnetism (Ha

¨

ma

¨

la

¨

inen et al. 1993,

Vrba 1996) (see SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications),

nondestructive evaluation (Wikswo 1995) (see SQUIDs:

Nondestructive Testing), NMR (Greenberg 1998) (see

SQUIDs: Amplifiers), and a vast array of basic science

experiments.

In the high-T

c

arena, the magnetic field sensitivity

achieved for d.c. SQUIDs is not vastly greater than

for RF SQUIDs. However, presumably because of

the complexity of the microwave system required for

the RF SQUID, most groups prefer the d.c. SQUID.

In contrast to the low-T

c

situation, there is not yet a

satisfactory high-T

c

junction technology; most devic-

es rely on grain boundary junctions. The white flux

noise of d.c. SQUIDs is unlikely to be reduced sig-

nificantly until better junctions—with a higher I

0

R

product—are realized. The 1/f noise of single-layer

devices is satisfactorily low, but in the case of mul-

tilayer structures—which have the lowest white

noise—it remains higher than is desirable. It is to

be hoped that work to improve the crystalline quality

of multilayers and of film edges will reduce the 1/f

noise. Further investment is also required to manu-

facture high-T

c

SQUIDs in reasonable quantities,

and thus reduce their price. However, despite these

remaining problems high-T

c

SQUIDs are now ex-

ploited in various applications, for example magne-

tocardiology (see SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications),

nondestructive evaluation (see SQUIDs: Nondestruc-

tive Testing), and magnetic microscopy (see SQUIDs:

Magnetic Microscopy).

Bibliography

Barone A (ed.) 1992 Principles and Applications of Super-

conducting Quantum Interference Devices. World Scientific,

Singapore

Chesca B 1998 Theory of RF SQUIDs operating in the pre-

sence of large thermal fluctuations. J. Low Temp. Phys. 110,

963–1001

Clarke J 1996 SQUID fundamentals. In: Weinstock H (ed.)

SQUID Sensors: Fundamentals, Fabrication and Applications.

Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Chap. 1, pp. 1–62

Drung D 1996 Advanced SQUID read-out electronics. In: We-

instock H (ed.) SQUID Sensors: Fundamentals, Fabrication

and Applications. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Greenberg Ya S 1998 Application of superconducting quantum

interference devices to nuclear magnetic resonance. Rev.

Mod. Phys. 70, 175–222

Ha

¨

ma

¨

la

¨

inen M, Hari R, Ilmoniemi J, Knuutila J, Lounasmaa O

V 1993 Magnetoencephalography—theory, instrumentation,

and applications to noninvasive studies of the working

human brain. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 413–97

1122

SQUIDs: The Instrument

Hilbert C, Clarke J 1985 DC SQUIDs as radio frequency am-

plifiers. J. Low Temp. Phys. 61, 263–80

Jaklevic R C, Lambe J, Silver A H, Mercereau J E 1964 Quan-

tum interference effects in Josephson tunneling. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 12, 159–60

Ketchen M B, Jaycox J M 1982 Ultra-low noise tunnel junction

d.c. SQUID with a tightly coupled planar input coil. Appl.

Phys. Lett. 40, 736–8

Koelle D, Kleiner R, Ludwig F, Dantsker E, Clarke J 1999

High-transition-temperature superconducting quantum in-

terference devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 631–84

Koelle D, Miklich A H, Ludwig F, Dantsker E, Nemeth D T,

Clarke J 1993 DC SQUID magnetometers from single layers

of YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

. Appl. Phys. Lett. 63, 2271–3

Mercereau J E 1970 Superconducting magnetometers. Rev.

Phys. Appl. 5, 13–20

Mu

¨

ck M, Andre

´

M-O, Clarke J, Gail J, Heiden C 1998 Radio-

frequency amplifier based on a niobium d.c. superconducting

quantum interference device with microstrip input coupling.

Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 2885–7

Tesche C D, Clarke J 1977 DC SQUID: noise and optimization.

J. Low Temp. Phys. 27, 301–31

Vrba J 1996 SQUID gradiometers in real environments. In:

Weinstock H (ed.) SQUID Sensors: Fundamentals, Fabrica-

tion and Applications. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Wikswo J P Jr 1995 SQUID magnetometers for biomagnetism

and nondestructive testing: important questions and initial

answers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 5, 74–120

Zhang Y, Yi H R, Schubert J, Zander W, Banzet M, Braginski

A I 1998 A design of planar multi-turn flux transformers for

radio frequency SQUID magnetometers. Appl. Phys. Lett.

72, 2029–31

Zimmerman J E, Thiene P, Harding J T 1970 Design and op-

eration of stable rf-biased superconducting point-contact

quantum devices, and a note on the properties of perfectly

clean metal contacts. J. Appl. Phys. 41, 1572–80

J. Clarke

University of California, Berkeley, California, USA

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic

Properties

Electrical steels are used in the cores of electromag-

netic devices such as motors, generators, and trans-

formers because of the ability of ferromagnetic

materials to magnify the magnetic effects of cur-

rent-carrying coils (see Magnets Soft and Hard: Mag-

netic Domains). Of the available ferromagnetic

materials, iron and its alloys offer the best cost ben-

eficial performance. The torque of a motor is pro-

portional to B

2

, where B is the intensity of

magnetization operating between its stationary and

moving parts. Because of this square law relationship

even small gains in B lead to useful increases in

torque and thus output power.

In the case of transformers, the large magnetiza-

tions available from iron enable voltage transforma-

tions to be carried out by windings of an acceptable

size. The voltage appearing at a transformer winding

is related to the rate of flux change dF/dt for the core

and is normally of sine form so that operation at high

peak flux levels is important.

It is clear that for steels to be of the most use for

electrical machines a high working induction is de-

sired, as close as practicable to the approximately 2 T

at which iron becomes saturated.

At the same time a high permeability (ratio of B to

H) or flux magnifying property is desired. The effec-

tive permeability of iron reduces as saturation is ap-

proached leading to heavier demands on magnetizing

current.

Additionally the duties of core steel must be exe-

cuted without serious wastage of energy within the

metal (called power loss or core loss) due to the pe-

riodic magnetic reversals involved in use.

The range of electrical steels available has arisen

out of the appropriate compromises struck between

these factors. Different types of steel suit different

applications (see Table 1).

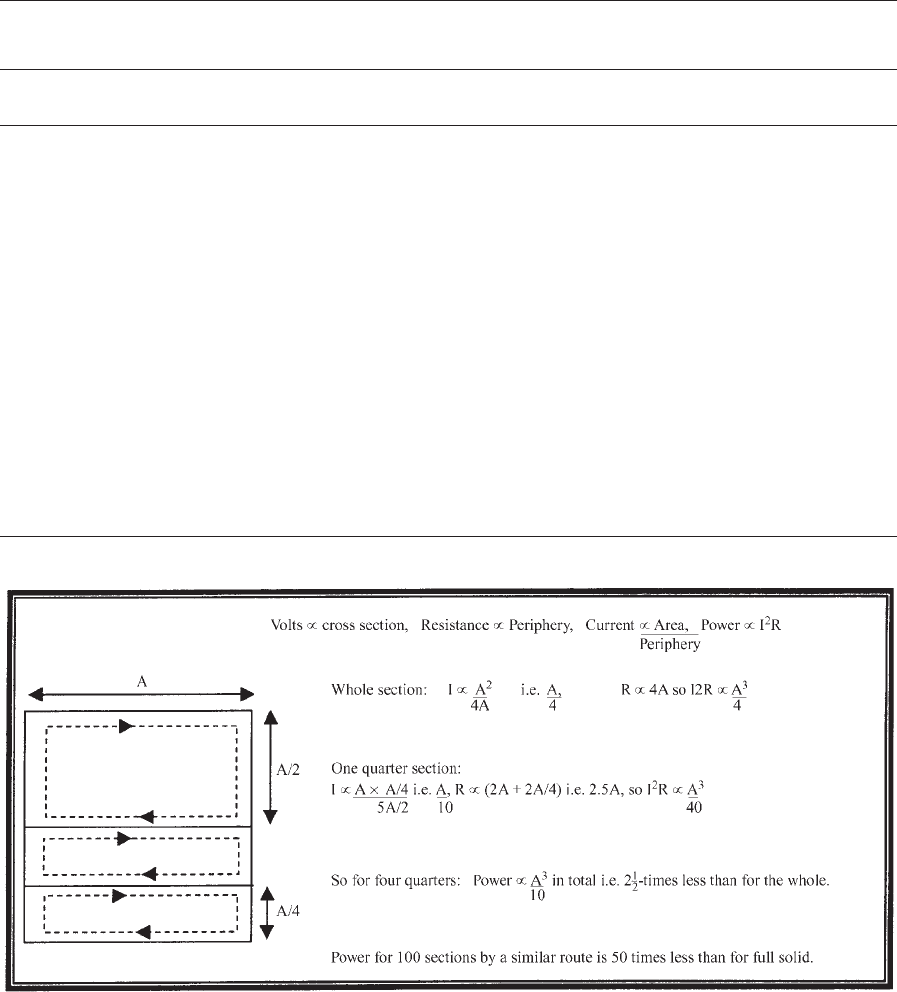

1. Reduction of Power Loss

One of the primary sources of power loss within an

electrical steel is eddy current loss (see Magnetic

Losses). If a solid iron core is placed within a mag-

netizing coil the iron core itself provides short-

circuited current paths in which so-called induced

‘‘eddy currents’’ can flow. These waste energy as heat

and also produce magnetic fields which oppose the

magnetization (Lenz’s law effects) so that penetration

of flux to the centre of the core is inhibited. Eddy

currents can be radically reduced by splitting up the

core into laminae which restricts the flow of eddy

currents (Fig. 1). There are limits to the degree of

lamination which can be applied set by the cost of

rolling steel to reduced thickness and the complexity

of handling this material for core building. Inevitably

as thinner steel is used the effective space occupancy

of the metal reduces since a pile of plates can never

have the same mass as solid metal of the same su-

perficial dimensions.

Further the need to insulate laminae from each

other by applying coatings reduces the effective space

occupancy. Overall the effect is to reduce the appar-

ent saturation induction of the core. Lamination cre-

ates much more metal surface, and surfaces produce

power loss due to domain wall pinning.

A second means of restraining eddy currents is the

use of alloying elements added to iron. Adding some

3% of silicon to iron raises its resistivity fourfold.

Many other elements have been tried as resistivity

raisers (e.g., aluminum) but silicon has proved to be

the most useful. Adding silicon certainly reduces eddy

currents (and so power loss) but the resulting alloys

are more difficult to roll and harder to punch into

laminations. Further, added silicon dilutes the iron

1123

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic Properties

present and reduces saturation magnetization and

high field permeability.

A second major component of power loss is hys-

teresis loss. If a plot is made of B vs. H over a cycle of

magnetization then the area of the resulting B–H

loop represents lost energy. The mechanism of this

so-called ‘‘hysteresis loss’’ relates to the fact that the

magnetization in iron functions via ferromagnetic

domain wall motion (see Magnetic Hysteresis). Easy

domain wall motion is impeded by non-magnetic in-

clusions in the steel, stressed regions and unfavorable

surface states. Clearly it is advantageous for the steel

Table 1

Typical electrical steels.

Type of steel Thickness Power loss

Conventional

density (g cm

3

) Relative permeability Usage

Non-oriented motor

grade requiring

customer anneal

0.65 mm 7.0 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.5 T,

50 Hz

7.85 3000 at 1.5 T Small

Non-oriented

superior motor

grade, requiring

customer anneal

0.5 mm 3.8 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.5 T,

50 Hz

7.85 3000 at 1.5 T Small/medium

motors

Non oriented fully

annealed

0.5 mm 5.3 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.5 T,

50 Hz

7.75 1620 at 1.5 T Larger rotating

machines small

transformers

Non oriented fully

annealed

0.35 mm 2.25 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.5 T,

50 Hz

7.60 660 at 1.5 T Large rotating

machines

Grain oriented steel

(CGO)

0.27 mm 0.78 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.5 T,

50 Hz

7.65 1.83 T at

800 A m

1

Rel m

1830 at 1.83 T

Transformers

High permeability

grain oriented steel

0.27 mm 0.98 W kg

1

B

ˆ

1.7 T,

50 Hz

7.65 1.93 T at

800 A m

1

Rel m

1930 at 1.93 T

Transformers

Relay soft iron 1.0 mm – 7.85 Coercive field

strength

56–80 A m

1

Figure 1

Lamination restrains eddy currents and reduces power wastage—a simplified model.

1124

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic Properties

to be inclusion-free (high purity) and free from stress.

Domain wall pinning occurs at surfaces so that no

more surface than is appropriate should be created

(i.e., steel not too thin). The bonding of coatings to

steel can produce effective roughness at the coating/

steel interface which pins domain walls and adds to

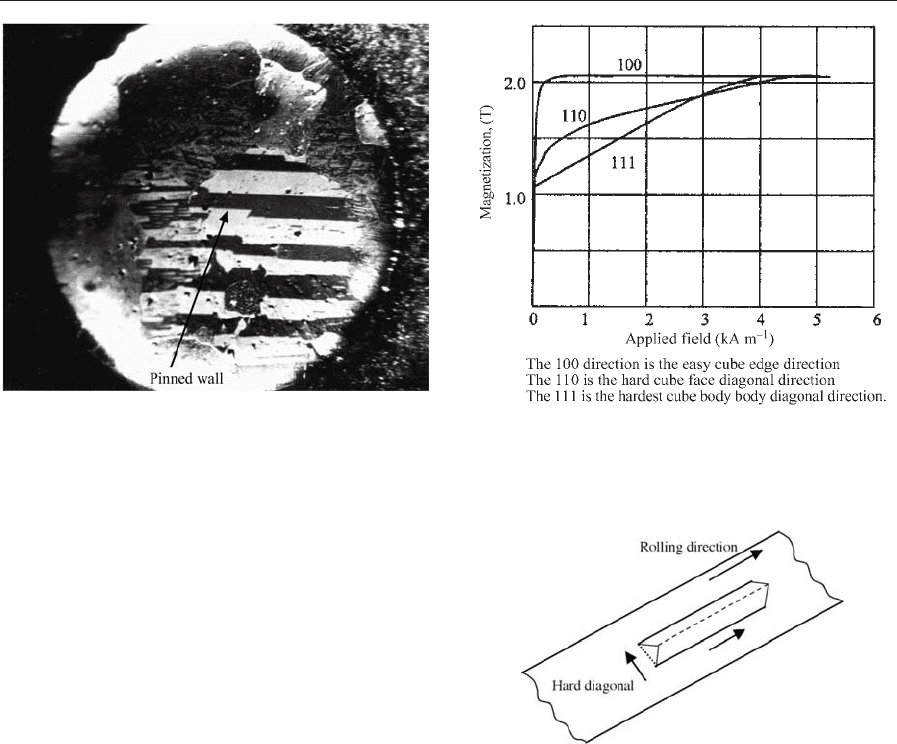

hysteresis loss. Figure 2 shows the domain structure

in an electrical steel in which a domain wall is clearly

shown with part of its length pinned.

A further contribution to loss reduction comes

from increasing grain size of the steel. With larger

grains (crystallites) there is less grain boundary per

unit volume. Grain boundaries are prime domain

wall pinning sites. Special rolling and heat treatment

regimes are used to promote grain growth. Appro-

priate heat treatments also relieve stress.

Permeability (in certain directions) can be en-

hanced by growing grains in which the easy direction

of magnetization of the iron lattice (Fig. 3) is caused

to lie along the direction in which magnetization is

desired. This process of ‘‘grain orientation’’ is com-

monly based on the creation of directionally organ-

ized impurity particles, which act to inhibit grain

growth in directions other than that desired. To per-

form this operation, impurities are purposely added

to steel at the melting stage (e.g., manganese sulfide,

aluminum nitride) so that during subsequent metal-

lurgical operations grains with easy directions of

magnetic response in the rolling direction of produc-

tion are grown preferentially. Figure 4 shows the ori-

entation for the most used Goss grains system.

The statistics of grain growth require that if only

certain nuclei are allowed to grow, then from a re-

duced population the resulting grains will be large. In

so-called conventional grain oriented (CGO) steel

grains are some 3–4 mm across in metal 0.27 mm

thick. The easy direction of magnetization of the

grains lies within a spread of a few degrees about the

rolling direction.

The desire to get the very highest in-rolling-direc-

tion permeability from steel has led to the devising of

better and better grain growth inhibitors so that the

so-called ‘‘improved oriented steel’’ can have a

directionality spread of only 1–21. This precision

has arisen from the requirement that only super-

accurately oriented nuclei grow. The growth statistics

now lead to grains, which may be 2–3 cm across. This

sounds good as orientation is excellent and grain

boundaries are few.

However, the magnetic energy considerations with-

in a grain dictate that large grains support wide do-

main wall spacings. With a wide domain wall spacing

walls must move more rapidly to execute the required

Figure 2

Magneto-optic image of ferromagnetic domains.

Figure 3

Responses to magnetizing fields of different crystal

directions.

Figure 4

A ‘‘Goss-oriented’’ crystal’s relationship to the sheet

rolling direction.

1125

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic Properties

flux reversal. A rapidly moving domain wall is a di-

ssipative item due to the micro eddy currents induced

by its movement.

This effect can be countered to some degree by

creating artificial grain boundaries and reducing the

domain wall spacing. Such artificial grain boundaries

can be created by lines of mechanical damage or

stress, or even gross displacement of metal at the steel

surface. Such domain refinement can use laser treat-

ments, spark ablation, ball scribing, etc., to give the

desired effect. Figure 5 shows the effect of domain

refinement.

The addition of silicon not only restrains eddy

currents but improves medium-field permeability and

reduces the tendency for losses to rise over time due

to the occurrence of fine precipitates within grains.

It is often suggested that eddy current losses in-

crease with the square of frequency of excitation and

hysteresis losses linearly. However, complex domain

interactions produce losses in excess of this simple

model. From the point of view of machine-design

engineers, losses are fairly well described by the

equation:

Loss ¼ Af þ Bf

2

ðf ¼ frequencyÞ:

Here A is a coefficient linked to hysteresis, though

not exclusively, and it is increased by the effects of

stress and impurities. B is a coefficient influenced by

material thickness and resistivity, but also by domain

wall spacing.

In general power loss increases with the amplitude

of magnetization and the hysteresis component rises

with approximately the 1.6 power of B

max

. This is a

useful indicator within the normal range of magnet-

izations.

2. Steel for Transformers

The production of grain orientation is very valuable

for materials destined for use in transformers since

unidirectional flux is employed (except at joints and

corners). In cores where the percentage of corner re-

gion is relatively high conventional grain oriented

steel may be preferred as the less exact orientation

eases flux rotation at corners. Figure 6 shows cores of

differing aspect ratio. Where the long limbs and

smaller percentage of corner is used the super-ori-

ented steel can be best exploited. It is usual to employ

super-oriented steel at higher working inductions

(B

max

1.7 T and above) than is usual for CGO

(B

max

E1.5 T). However, in any system over voltage

can more rapidly take steel operating at B

max

1.7 T

into technical saturation when severe unwanted mag-

netizing currents will flow.

3. Steel for Rotating Machines

Grain orientation of the Goss type is unsuitable

for the cores of most motors and generators where

properties need to be equal at all angles in the plane

Figure 5

Example of domain refinement.

Figure 6

(a) A core with low aspect ratio, (b) a core with high

aspect ratio.

1126

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic Properties

of the sheet. Here the benefits of lamination and

added silicon still apply and enhanced purity with

large grains is desirable. Large grains can be pro-

duced by two main methods.

3.1 Long Hot Anneal

Steel strip can be annealed at about 1000 1Cina

strand anneal line so that grains may grow to some

tens of microns in diameter. Combined with a mod-

erate amount of added silicon, e.g., 1–3%, a good

core material is produced which is nearly isotropic.

After such an anneal the steel is soft but the added

silicon raises hardness to a degree where stamping

into motor laminations is fairly convenient.

3.2 Critical Grain Growth

Here strip steel is annealed in a strand anneal line

then given a small amount of cold rolling, reducing

thickness by about 8%. This is just enough cold work

to build in sufficient strain energy to provide ‘‘explo-

sive’’ grain growth when the metal is re-heat treated

at about 800 1C. This can usefully be applied after

stamping of the steel which was done while still hard

from cold rolling. The removal of stamping stress is

combined with the beneficial effects of critical grain

growth.

3.3 Decarburization

A strand anneal conducted in wet hydrogen, e.g.,

800 1C and a dew point of 65 1C enables dissolved

carbon to be removed down to some 0.003%. This

practice helps reduce hysteresis loss.

Further, end users can make the final post-stamp-

ing anneal a decarburizing anneal. In recent years it

has become possible to reduce carbon to very low

levels at the steel making stage of production so that

anneals can be conducted in a neutral gas, e.g.,

nitrogen. The application of a wet hydrogen anneal

when carbon is already low can damage the metal by

the production of sub-surface oxidation which harms

permeability.

A wide range of highly developed methods exists

for the management of lamination annealing for

stress removal and decarburization.

4. Coatings

A variety of coatings are used on electrical steels. On

grain oriented steel a magnesium oxide coating is

applied to the steel before final anneal so that the

sulfur which was introduced to control grain growth

for orientation can be finally removed. This coating

reacts with the silicon in the steel to yield a magne-

sium silicate glass, which is both insulative and able

to apply tension to the steel substrate due to the low

thermal expansivity of the glass A supplementary

tensile coating may be applied on top of the glass.

Tension in the steel refines the ferromagnetic domain

structure and reduces power loss. Non-oriented steel

may be given a fully organic coating which aids

stamping (no further anneal used), or it may require a

mixed organic/inorganic coating, part of which sur-

vives anneal.

For small machines, e.g., below kilowatt size, in-

terlaminar insulation is not very dependent on ap-

plied coatings and provided that stamping burrs do

not create unwanted current paths losses do not rise

unduly.

A suitable coating can prevent sticking of lamina-

tions when these are annealed in stacks. More re-

cently coatings have been developed which are able to

survive cold rolling aimed at eventual critical grain

growth so that the overall process is simplified.

5. Relay Steels

Electrical steels are normally classified by power loss,

and further by permeability. Unalloyed iron intended

for use in electromechanical relays is classified by

coercive force. (H needed to bring B to zero after full

magnetization in ampere-meters). Table 1 shows

some typical properties of electrical steels.

6. Conclusions

Silicon–iron alloys represent the most widely used

and most cost beneficial core materials for devices

used in electric power handling.

See also: Magnetic Steels

Bibliography

Beckley P 1999 Modern steels for transformers and machines.

IEE Eng. Sci. J. (Aug), 149–59

Beckley P, Thompson J E 1970 Influence of inclusions on

domain wall motion and power loss. Proc. IE 117 (Nov),

2194–200

P. Beckley

Newport, UK

Stress Coupled Phenomena:

Magnetostriction

In terms of a simple atomic description the equilib-

rium distances between the constituents of solid mat-

ter are mainly determined by forces between electric

charges and the thermal energy. These distances can

1127

Stress Coupled Phenomena: Magnetostriction

be altered by externally applied mechanical forces

resulting in deformations usually described by the

tensor of strains e. In substances exhibiting an or-

dered structure of atomic magnetic moments the

magnetic interaction energy contributes to the total

energy and causes additional deformations e

M

. For a

ferromagnetic substance with spontaneous magneti-

zation, M

S

, these magnetically caused deformations

have an isotropic part, resulting in volume changes

proportional to M

2

S

(Ne

´

el 1937) and an anisotropic

part (depending on the direction of M

S

). e

M

is con-

nected with the elastic tensor by means of so-called

magneto-elastic coupling constants. If M

S

is rotated,

e.g., by an external magnetic field, the deformations

e

M

are changed resulting in macroscopic deforma-

tions, Dl, of a sample, often denoted as magneto-

striction.

1. Volume Magnetostriction (k

V

¼DV/V)

This type of magnetostriction can be observed in

cases where M

S

is altered either by strong magnetic

fields or near the temperature of a magnetic phase

transition, e.g., the Curie temperature for ferromag-

nets. In most cases l

V

is proportional to the magnetic

field strength H. In practicable magnetic fields the

slope l

V

/H is small (B10

13

–10

12

m

´

/A

1

). Near the

Curie temperature T

C

, however, M

S

can be consid-

erably enhanced by moderate fields. Recently, values

of l

V

/HE10

8

m

´

/A

1

were reported for La(Fe

0.88

Si

0.12

)

13

at T ¼200 K (Fujita and Fukamichi 1999).

On the other hand, M

S

changes dramatically with

temperature near T

C

for a constant field and may

induce volume changes equal to or larger than the

thermal expansion.

2. Joule Magnetostriction k

J

¼(Dl/l)

anis

The anisotropic part of magnetic deformations was

discovered by Joule more than 150 years ago and is

therefore often called Joule magnetostriction. In poly-

crystalline materials with statistically distributed

crystalline axes it depends on the angle y between

/M

S

S and the measuring direction where /M

S

S is

the volume averaged spontaneous magnetization:

l

J

¼ð3=2Þl

S

ðcos

2

y /cos

2

y

0

SÞ

Here l

S

denotes the saturation value of l and

/cos

2

y

0

S is the mean value of cos

2

y in the initial

state. In a single crystal (Dl/l)

anis

additionally depends

on the direction of M

S

with respect to the crystalline

lattice and is, therefore, described by several aniso-

tropy constants l

n

depending on the lattice type as

well as on the material. Cubic materials, e.g., iron,

nickel, and many alloys, are described by two con-

stants l

100

and l

111

measured for the cases where the

direction of M

S

, and that of the measurement, are

parallel to the lattice directions [100] and [111],

respectively. Therefore,

l

J

¼ð3=2Þl

100

½ða

2

x

b

2

x

þ a

2

y

b

2

y

þ a

2

z

b

2

z

Þ1=3

þ 3l

111

ða

x

a

y

b

x

b

y

þ a

y

a

z

b

y

b

z

þ a

z

a

x

b

z

b

x

Þ

where a

i

and b

i

are the direction cosines of M

S

and the

measurement direction with respect to the crystal ax-

es, respectively. Usually l

n

values are of different

magnitude and may even have opposite signs. A typ-

ical example is iron with l

100

¼24 10

6

and l

111

¼

–22 10

6

. Iron often serves as illustration of the

apparently complicated dependence of l

J

as a func-

tion of the field strength. The behavior can simply be

explained in terms of magnetic domains. According to

the magnetocrystalline anisotropy of iron in small

fields the magnetization inside each domain is essen-

tially parallel to one of the three /100S axes and

gets closer to the field direction by shifting the walls

between differently oriented /100S domains, this

results in a positive Dl/l. With an increasing field

strength, however, M

S

is rotated away from the

/100S direction. Then, due to the higher probability

to find one of the four /111S axes near the field

direction, the negative contribution of l

111

dominates

the initial positive change.

3. Theory

3.1 Phenomenological Approaches

The simplest way to describe magnetostrictive effects

is through mathematical phenomenology: to calcu-

late the dependence of magnetization M and strain e

on magnetic field H and stress s one introduces the so

called path-dependent differentials (PDD), the inte-

gration of which over the material history should

recover the correct M and e behavior. The goal is to

construct these PDDs using as few adjustable para-

meters as possible and yet with enough predictive

power to make this approach useful.

By a ‘‘physical’’ macroscopic treatment of magne-

tostriction the magnetization M is presented as the

sum of reversible M

r

and irreversible M

irr

contribu-

tions. M

r

can then be expressed as a function of the

effective field H

eff

, which, in turn, depends on the

magnetization state and elastic stress. The changes of

M

irr

can be due to various dissipative processes, e.g.,

domain wall motion. The theory in its simplest form

(for an isotropic material) results in a system of non-

linear equations that depend on M and magneto-

striction l(M) (which is also assumed to exhibit

hysteresis). The input parameters of the theory (be-

sides the standard material characteristics) are, e.g.,

the pinning constant and the initial magnetic suscep-

tibility (Sablik and Jiles 1993).

The ‘‘microscopic’’ approach, which should be

able to predict not only the average properties of

1128

Stress Coupled Phenomena: Magnetostriction

magnetostrictive materials but also their microscopic

features, is based on the minimization of the magneto-

elastic free energy, written as a function of the mag-

netization M(r) and deformation e(r) of a magnetic

body (James and Kinderlehrer 1994). The energy

minimization itself can be carried out either analyti-

cally (for simplest cases) or numerically. However,

numerical methods, which would allow self-consis-

tent computations of magnetization structures and

deformation fields in a general three-dimensional

case, are not yet available.

3.2 Ab Initio Calculations

First principles calculations of magnetostriction con-

stants are now possible for two kinds of magnetic

materials:

(i) In transition metals like iron, cobalt, and nick-

el, where itinerant electrons are responsible for mag-

netic order, the spin-orbit coupling which leads to the

magnetostrictive effects is weak and can be treated

using the perturbation theory. Due to the complicat-

ed band structure of transition metals, corresponding

numerical calculations of the magnetocrystalline an-

isotropy energy E

MCA

(its derivative, with respect to

the lattice strain e, provides information about the

magnetostriction constant l) are very tedious. How-

ever, due to recent methodological progress, mono-

tonic and numerically stable dependencies of E

MCA

(e)

can be obtained (Wu et al. 1998) leading to a rea-

sonable quantitative agreement (within 15–30%) be-

tween the experimentally measured l-values and

theoretical results.

(ii) In most rare earth elements magnetic proper-

ties are dominated by localized f-electrons, and the

corresponding spin-orbit coupling is so large that the

opposite limit of infinite coupling is a good basis for

the calculations. In this limit the charge density of the

f-shell is assumed to follow the orientation of the

atomic magnetic moment in an applied field. Due to

the strong anisotropy of this charge density, a large

lattice distortion occurs on rotation of these f-elec-

tron clouds, thus leading to huge magnetostriction.

Corresponding ab initio calculations (Buck and

Fa

¨

hnle 1998) require the determination of the equi-

librium lattice constants of rare earth compounds

when the sample magnetic moment is oriented along

various crystallographic directions. Magnetostriction

l can then be determined from the relative difference

between these constants. Unfortunately, a compari-

son with experimental data is difficult at present due

to their relatively poor quality.

4. Applications

Volume magnetostriction can be used to adjust the

thermal expansion coefficient in certain temperature

regions, e.g., for invar and covar alloys. The latter is

widely used for metal-glass seals and in large cooling

cells for liquid hydrogen shipping. Joule magneto-

striction was initially used for ultrasound generators

and is, at present, applied in many other systems as

well. A material composed of two compounds each

consisting of a rare earth element and iron is specially

designed for the generation of large elongations at

room temperature in small magnetic fields. One of

them (TbFe

2

) yields a giant saturation magneto-

striction. It needs, however, a high magnetic field

strength. The other (DyFe

2

) is added to TbFe

2

in

order to make the combination magnetically soft.

The optimized substance containing about 70%

DyFe

2

yields a l

S

E2 10

3

at room temperature in

a moderate magnetic field and is, therefore, an ideal

material for actuators and transducers. Recently, a

plan was conceived which would achieve a high mag-

netostriction combined with a high saturation mag-

netization. This can be realized by using multilayers

consisting of thin films of amorphous TbFe and films

of Fe–Co alloys (Quandt and Ludwig 1999). These

systems are tailored for applications in optical scan-

ners, micro-valves, linear and rotation micro-motors

and micro-pumps. It should be pointed out that this

class of substances provides a conversion factor from

magnetic to mechanical energy of nearly one.

5. New Effects in Thin Films and Multilayers

In ultra thin films and multilayers new effects, due to

interfaces and large strains, were found. Interfaces

give a remarkable contribution to the magneto-elastic

coupling at film thicknesses smaller than several nm

resulting, e.g., in nearly magnetostriction free

Co

50

Fe

50

films at a film thickness of about 1.6 nm.

Co

50

Fe

50

is an alloy with the high saturation magne-

tostriction of 80 10

6

in the bulk state. In poly-

crystalline iron films the saturation magnetostriction

changes its sign at a film thickness of 5 nm. In systems

where, due to epitaxial growth, giant strains in the

range of several percent can be obtained, higher order

magneto-elastic coupling coefficients are observed

(Sander et al. 1999). Their magnitude is comparable

even with the usually dominating linear ones. Trig-

gered by these new experimental findings both the

scientific and the practical importance of magneto-

striction effects have recently received considerable

attention.

See also: Magneto-elasticity in Nanoscale Hetero-

genous Materials; Magnetostrictive Materials

Bibliography

Buck S, Fa

¨

hnle M 1998 Ab initio calculation of the giant mag-

netostriction in Te and Er. Phys. Rev. B57, R14044–7

Chikazumi S 1997 Physics of Ferromagnetism. Clarendon,

Oxford

1129

Stress Coupled Phenomena: Magnetostriction