Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

enter the planes of the cube, and so form lines parallel

to each crystallographic direction of the crystal (Fig. 8).

It is believed that this extraordinary structural feature

is mainly responsible for the relatively high T

c

softhe

compounds. Due to technological considerations with

respect to processing and fabrication, only Nb

3

Sn

(T

c

¼ 18:1 K) is used for the manufacturing of wires

forhighfield(45 T) superconducting magnets.

MgB

2

has been found to be superconducting at a

T

c

of 39 K and a B

c2

at about 11 T. This new Type 2

superconductor has a hexagonal structure (AB

2

) with

a ¼ 3:086

(

A and c ¼ 3:524

(

A. Although the com-

pound has quite low T

c

and B

c2

values (about 15 T at

4.2 K and 10 T at 20 K), it is of considerable interest

for the processing of wires used for the construction

of superconducting magnets operating at 1–2 T and

20 K, due to its comparably low price and excellent

workability. In addition, it is hoped that besides

MgB

2

other superconducting compounds of this new

class of superconductors with T

c

s much higher than

39 K will be found.

Superconductivity has been found in different ma-

terials (Table 1), which indicates that superconduc-

tivity is not only related to one or two structural

types, but may occur everywhere.

4.1 High-temperature Superconducting Cuprates

Since the first high temperature superconductor

(HTSC) based on copper oxide with the composition

La

0.85

Ba

0.115

CuO

3

was found, a variety of high-tem-

perature superconductors have been synthesized. They

all share a single structural feature, namely supercon-

ducting two-dimensional sheets of CuO

2

consisting of

corner-shared CuO

4

units. The sheets are separated by

a nonsuperconducting layer which supplies the sheets

with charge carriers. The HTSCs can be divided into

three major groups: (i) REEBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

(123 type);

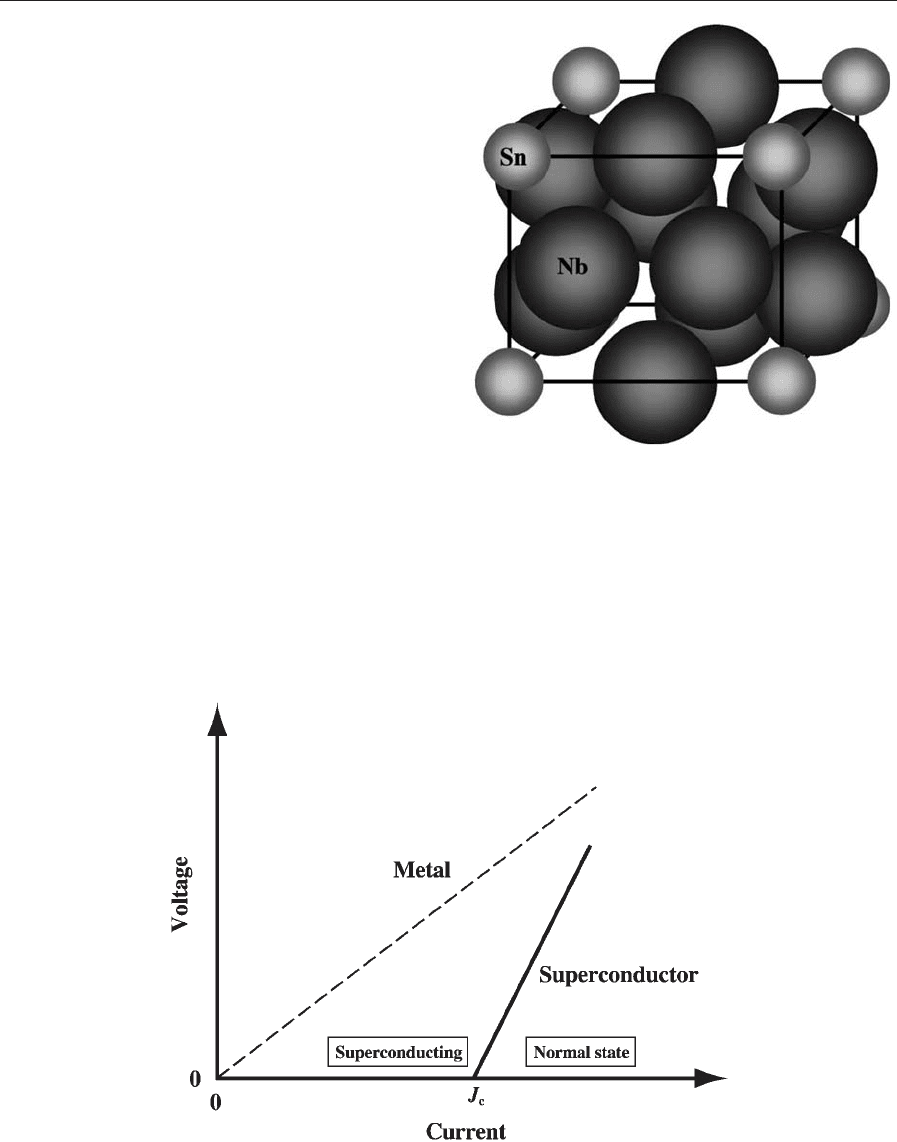

Figure 7

Current–voltage characteristic of a superconductor.

Figure 8

Crystal structure of A15 phases (Nb

3

Sn).

1140

Superconducting Materials, Types of

(ii) AB

2

Ca

n1

Cu

n

O

2n þ2.5

(1223 type); (iii) A

2

B

2

Ca

n1

Cu

n

O

2n þ4

(2223 type) with REE ¼ rare earth ele-

ments; A ¼ Bi, Tl, Hg; B ¼ Sr, Ba. The phases have a

pronounced layered structure which is visible both

microscopically (Fig. 9) and macroscopically (Fig. 10).

Due to the significantly different parameters of the a,

b, and c axis, the crystallization rate in direction of

the a,b plane is about 10

2

–10

3

times faster than in c

direction.

Compared with low-temperature superconductors

of Type 2, the cuprates behave very differently with

respect to their superconducting properties vs. the

temperature. Their resistivity transition is broader

and the breadth increases rapidly with the applied

field. This means that there is a region below B

c2

where the material shows a substantial electrical re-

sistance, although the material is superconducting

with respect to quantum mechanical considerations.

This region is shown in Fig. 11 between B

c2

and the

irreversibility line, B

irr

. Below B

irr

the resistance of

the material is zero. The substantial resistance above

B

irr

corresponds to very easy flux flow.

The layered structure also implies a pronounced

anisotropy of the properties, causing the so-called

Table 1

Superconducting elements, alloys, and compounds.

Material Temperature (K) Material Temperature (K)

Elements A15 phases

Carbon (C) 15 Nb

3

Ge 23.2

Lead (Pb) 7.2 Nb

3

Si 19

Lanthanum (La) 4.9 Nb

3

Al 19

Tantalum (Ta) 4.47 Nb

3

Sn 18.1

Mercury (Hg) 4.15 V

3

Si 17.1

Tin (Sn) 3.72 Ta

3

Pb 17

Indium (In) 3.40 V

3

Ga 16.8

Thallium (Tl) 1.70 Nb

3

Ga 14.5

Rhenium (Re) 1.697 V

3

In 13.9

Protactinium (Pa) 1.40

Thorium (Th) 1.38 High-temperature superconductors

Aluminum (Al) 1.175 HgBa

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

8

138

Gallium (Ga) 1.10 HgBa

2

CaCu

2

O

6

124

Gadolinium (Gd) 1.083 HgBa

2

CuO

4

98

Molybdenum (Mo) 0.915 Tl

2

Ba

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

127

Zinc (Zn) 0.85 TlBa

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

9

123

Osmium (Os) 0.66 TlBa

2

Ca

3

Cu

4

O

11

112

Zirconium (Zr) 0.61 Tl

2

Ba

2

Ca

3

Cu

4

O

12

112

Americium (Am) 0.60 Bi

2

Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

110

Cadmium (Cd) 0.517 Bi

2

Sr

2

CaCu

2

O

8

Ruthenium (Ru) 0.49 Bi

2

Sr

2

CuO

6

20

Titanium (Ti) 0.40 Ca

1x

Sr

x

CuO

2

(at about 5 GPa) 110

Uranium (U) 0.20 TmBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

90

Hafnium (Hf) 0.128 GdBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

94

Iridium (Ir) 0.1125 YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

93

Lutetium (Lu) 0.100 Pb

2

Sr

2

YCu

3

O

8

70

Beryllium (Be) 0.026 GaSr

2

(Y, Ca)Cu

2

O

7

70

Tungsten (W) 0.0154 La

1.85

Ba

.15

CuO

4

35

Platinum (Pt) 0.0019 (Nd,Sr,Ce)

2

CuO

4

35

Rhodium (Rh) 0.000325 Pb

2

(Sr,La)

2

Cu

2

O

6

32

La

1.85

Sr

0.15

CuO

4

38

Metals and alloys

Nb0.6Ti0.4 9.8 Various superconductors

Nb 9.25 Cs

3

C

60

40

Tc 7.80 MgB

2

39

V 5.40 Ba

0.6

K

0.4

BiO

3

30

YNi

2

B

2

C 15.5

LiTiO

2

13

1141

Superconducting Materials, Types of

‘‘two-dimensional superconductivity’’ parallel to the

a,b plane. For example, the critical current density as

well as the B

c1

and B

c2

values of the compounds, are

significantly greater parallel to the a,b plane than

parallel to the c axis (Fig. 12). In addition, due to the

almost complete decoupling of the CuO

2

sheets by

the nonsuperconducting (Bi, Tl, Hg)O sheets, the

HTSCs behave very differently within an applied

magnetic field. At temperatures below about 30 K

flux lines are formed above B

c1

like in the Type 2 low-

temperature superconductors. Above that tempera-

ture, the flux lines disappear and separated, almost

two-dimensional, flux disks, the so-called pancake

vortices, are formed within the CuO

2

sheets (Fig. 13).

The coupling between the pancakes is very weak, es-

pecially at high temperatures, for example 77 K (boil-

ing point of liquid nitrogen), so that the pancakes are

moving independently from the neighboring pancake

of the next CuO

2

sheet when a Lorenz force is ap-

plied. Pinning of these pancakes is almost impossible

and therefore, the J

c

decreases significantly in an ap-

plied magnetic field (Fig. 14).

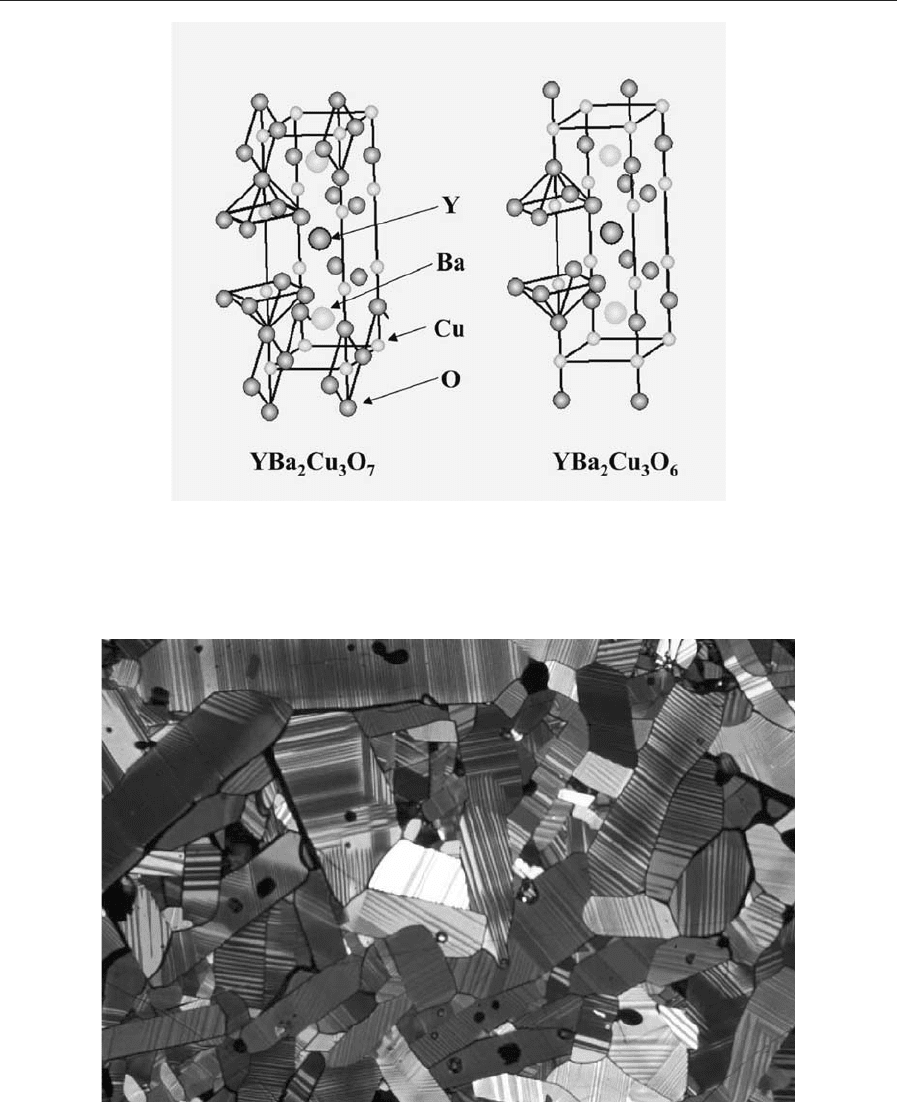

4.2 The Compound YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

One of the main important high temperature super-

conducting cuprates is the compound YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

,

better known as the ‘‘123 phase’’ (T

c

¼ 93 K). The

123 phase is characterized by a Cu–O sublattice con-

sisting of the CuO

2

sheets parallel to the crystallo-

graphic a–b plane, and Cu–O chains parallel to the

crystallographic a axis (Fig. 15). The yttrium atom

enters the center of the unit cell, and separates the

Cu–O sheets. At temperatures of above 700 1C the

compound is tetragonal with a ¼ 3:857

(

A and

c ¼ 11:839

(

A. Below that temperature, the phase be-

comes orthorhombic with a ¼ 3:885

(

A, b ¼ 3:818

(

A,

and c ¼ 11:680

(

A due to the introduction of excess

oxygen into the Cu–O chains.

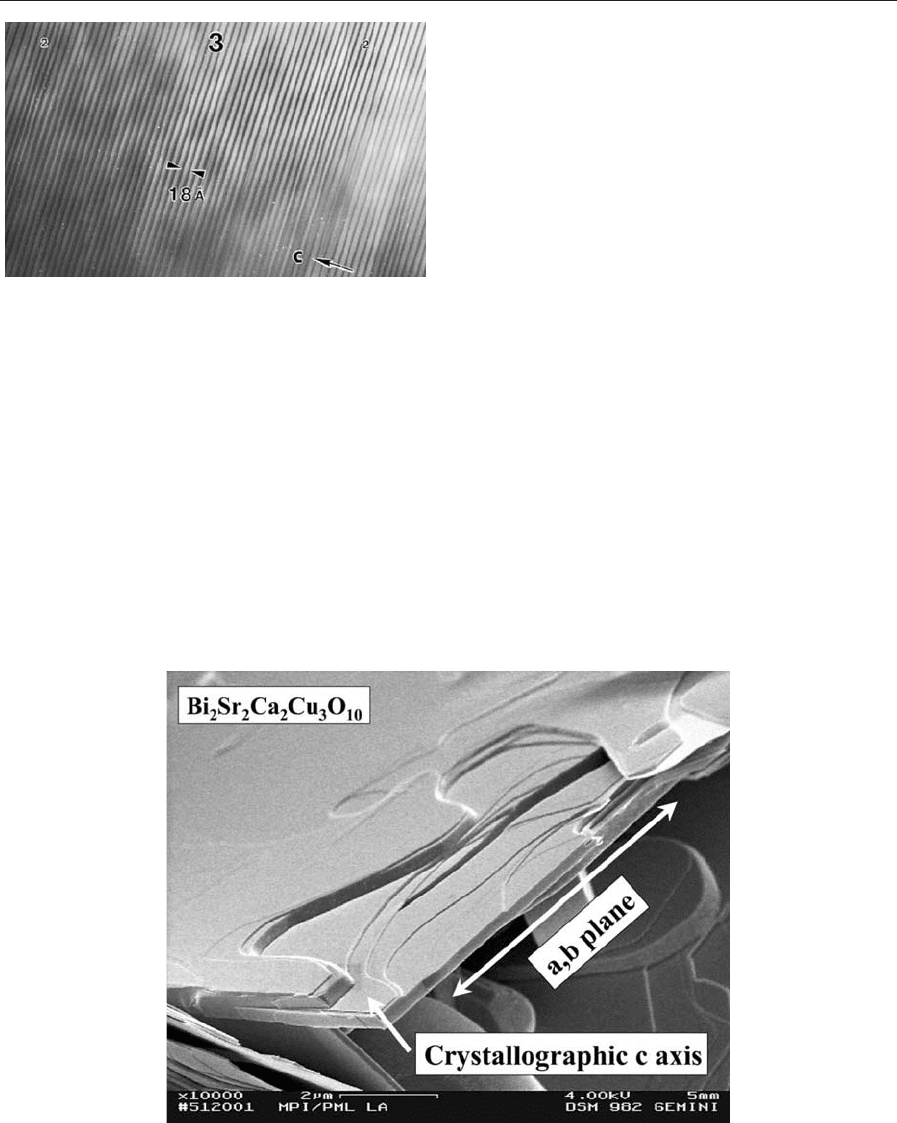

Figure 9

Transmission electron microscopic image of a

Bi

2

Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

crystal. Dark layers: BiO bilayers,

light gray layers: Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

7

. (3) area with

Bi

2

Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

structure; (2) Stacking faults with

Bi

2

Sr

2

CaCu

2

O

8

structure. (C) crystallographic c axis.

18 A

˚

represent a half unit cell of Bi

2

Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

.

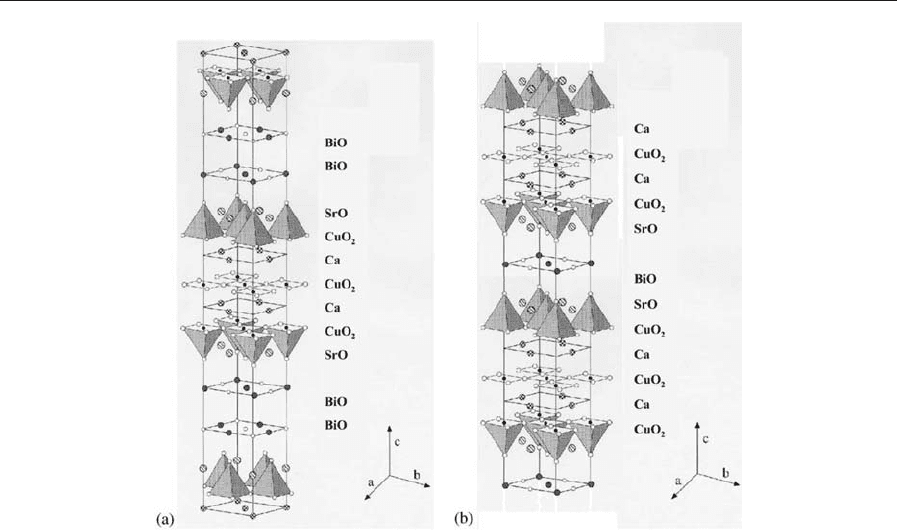

Figure 10

Scanning electron microscopic image of a Bi

2

Sr

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

crystal showing the extreme anisotropy in grain

dimension.

1142

Superconducting Materials, Types of

The phase transformation is combined with a for-

mation of elastic twins parallel to the crystallogra-

phic [110] plane. This phenomenon makes it easy to

distinguish between the tetragonal and orthorhom-

bic 123 phase using a microscope and polarized light

(Fig.16).TetragonalYBa

2

Cu

3

O

6

is nonsuperconduct-

ing. With increasing oxygen content the compound

becomes superconducting at about YBa

2

Cu

3

O

6.3

.

Maximum T

c

is reached at YBa

2

Cu

3

O

6.93

. A further

increase of the oxygen content decreases T

c

.

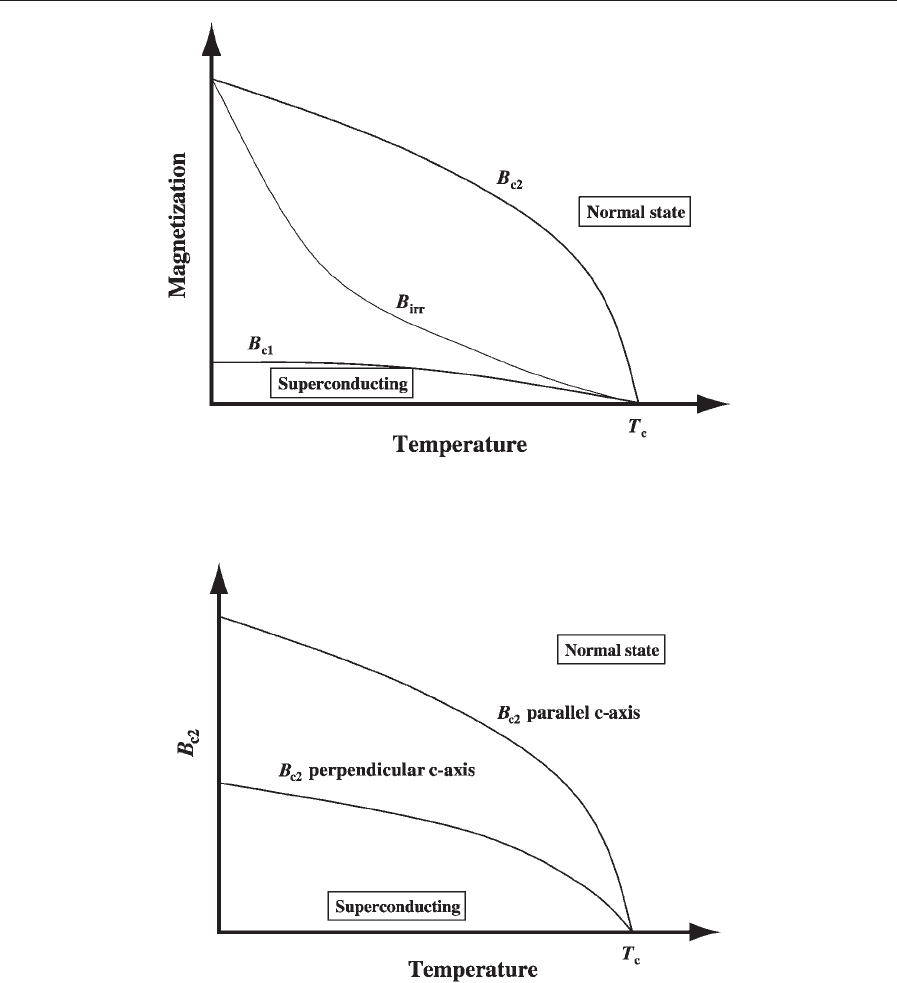

Figure 11

B

c111

, B

c2

, and B

irr

vs. the temperature.

Figure 12

Schematic drawing of the upper critical field vs. temperature parallel and perpendicular to the crystallographic c axis

showing the pronounced anisotropy of the superconducting properties of the HTSCs.

1143

Superconducting Materials, Types of

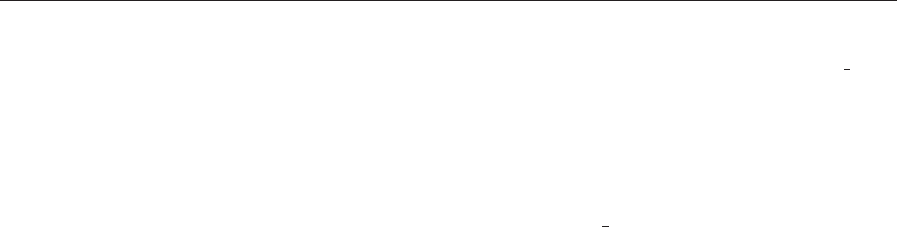

4.3 The 1223 and 2223 Type Compounds

The compounds have layered structures parallel to

the crystallographic a,b plane, consisting of (Bi,Tl,

Hg)O-layers which alternate with perovskite-like

B

2

Ca

n1

Cu

n

O

1 þ2n

units as illustrated in Fig. 17.

The Sr

2

Ca

n1

Cu

n

O

1 þ2n

units contain the CuO

2

sheets which are oriented parallel to the a,b plane.

The n ¼ 2 phase (1212 or 2212 phase) is characterized

by two CuO

2

sheets and the n ¼ 3 phase (1223 and

2223 phase) by three CuO

2

sheets, respectively. Thus,

the general structure of all members of the series

consist of CuO

2

sheets, that are separated by calcium

(for n 41) and covered in the c direction by (Ba,Sr)O

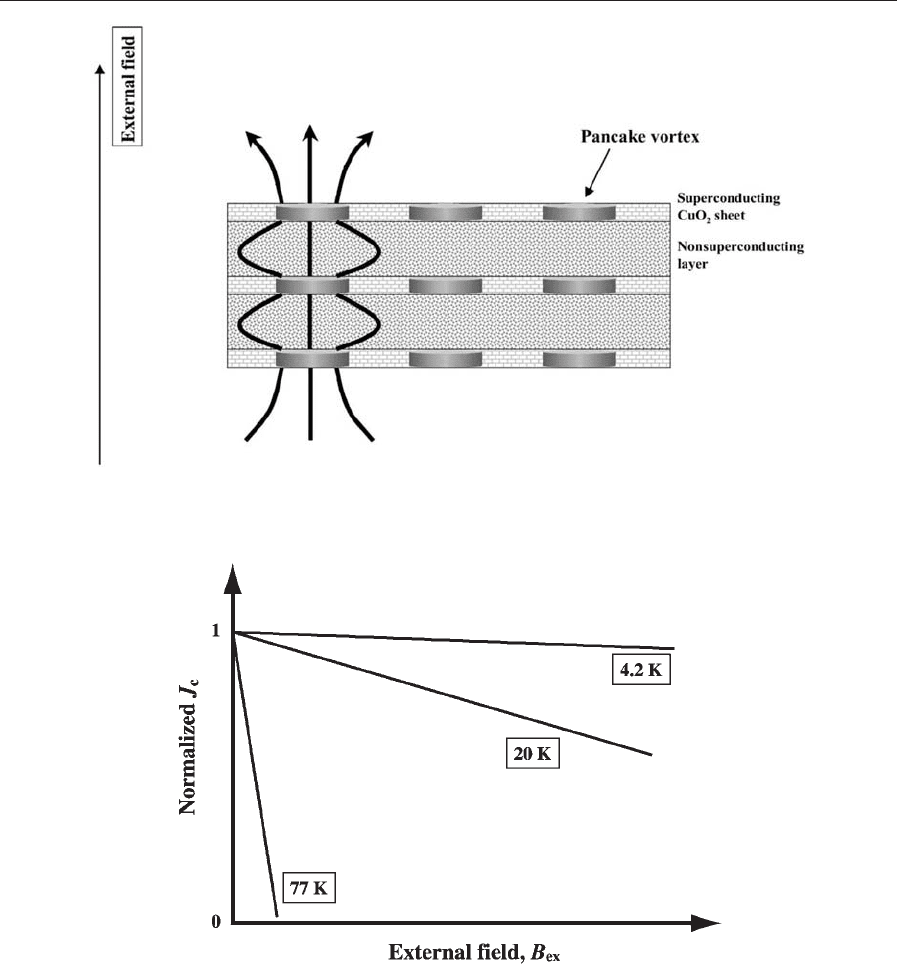

Figure 13

Pancake vortex in a HTSC parallel to the CuO

2

sheets.

Figure 14

Schematic drawing of the influence of the external field, B

ex

, on the J

c

value of HTSCs at different temperatures.

1144

Superconducting Materials, Types of

Figure 15

Crystal structure of tetragonal, nonsuperconducting YBa

2

Cu

3

O

6

, and orthorhombic, superconducting YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

.

Figure 16

Micrograph of a 123 ceramic using an optical microscope and polarized light showing the [110] twin boundaries in 123

grains.

1145

Superconducting Materials, Types of

sheets. These perovskite-like units alternate in c di-

rection with the (Bi, Tl, Hg)O-layers.

The T

c

s of the compounds are dependent on the

oxygen content and, like the 123 phase, they exhibit a

maximum T

c

at a certain oxygen content. However,

none of them become nonsuperconducting at low

oxygen contents, and the dependence of T

c

is very

different from compound to compound.

See also: Electrodynamics of Superconductors:

Weakly Coupled; Superconducting Thin Films:

Materials, Preparation, and Properties; Supercon-

ducting Thin Films: Multilayers; Superconducting

Permanent Magnets: Principles and Results

Bibliography

Bardeen J, Cooper N L, Schrieffer J R 1957 Theory of super-

conductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–204

Cava R J 2001 Oxide superconductors. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83,

5–28

Flu

¨

kiger R 1991 A15 compound superconductors. In: Advances

in Materials Science and Engineering. Pergamon, Oxford

Ginsberg D M (ed.) 1989 Physical Properties of High Temper-

ature Superconductors. World Scientific, Singapore

Lynn J W (ed.) 1990 High Temperature Superconductivity.

Springer, New York

Matthias B T, Geballe T H, Compton V B 1965 Superconduc-

tivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 35, 1–23

Meissner W, Ochsenfeld R 1933 Naturwissenschaften. 21, 787

Onnes H K 1911 Comm. Phys. Lab. Univ. Leiden, Suppl. No. 34

Park C, Snyder R L 1995 Structures of high-temperature

cuprate superconductors. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 78, 3171–94

Tinkham M 1975 Introduction to Superconductivity. McGraw-

Hill, New York (extended edn. 1995)

P. Majewski

Max-Planck-Institut fu

¨

r Metallforschung

Stuttgart, Germany

Superconducting Materials: BCS and

Phenomenological Theories

At very low temperatures many metals and alloys

undergo a second-order phase transition to a super-

conducting state in which there is no resistance to

flow of electricity. Superconductors exhibit other re-

markable phenomena such as exclusion of magnetic

flux from the interior (the Meissner effect) and flux

quantization. Phenomenological theories were devel-

oped to describe semiquantitatively different aspects

of superconductivity, including the Gorter–Casimir

Figure 17

(a) Crystal structure of the A

2

B

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

type HTSC with A ¼ Bi, Tl, Hg, and B ¼ Sr, Ba. (b) Crystal structure of

the AB

2

Ca

2

Cu

3

O

10

type HTSC with A ¼ Tl, Hg, and B ¼ Sr, Ba.

1146

Superconducting Materials: BCS and Phenomenological Theories

two-fluid model for thermal properties and the

London theory for electromagnetic properties. In

spite of many attempts, it was nearly 50 years from

the discovery of superconductivity in 1911 before a

microscopic theory based on pairing of electrons was

derived from quantum mechanics. The theory has

been able to account quantitatively for most proper-

ties of superconductors as well as to predict new

unexpected phenomena. Transition temperatures can

be derived essentially from first principles for the

simpler metals, but the theory has been less successful

in predicting new compounds with high transition

temperatures.

1. Outline of Phenomenological Theories

Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh

Onnes, only three years after he had liquefied heli-

um. He found that the resistance of a rod of frozen

mercury drops suddenly to zero when cooled to near

the boiling point of helium (4.2 K). It was soon found

that superconductivity is a common phenomena, ex-

hibited by many metals, alloys, and intermetallic

compounds when cooled below a critical temperature

T

c

. To show that the resistance really vanishes, Onnes

showed that a persistent current flows indefinitely in

a ring or solenoid with no voltage applied. In steady

state, the electric field in a superconductor vanishes

(E ¼0).

It was not until 1933 that Meissner discovered a

property that is even more basic; a superconductor

excludes a magnetic field (B ¼0). If a sphere or other

simply connected body is placed in a magnetic field

and cooled below T

c

, the flux in the interior is

expelled. If the field were applied when the sphere is

in the superconducting state, currents would be set up

near the surface to keep the flux inside from chang-

ing. They would flow indefinitely, so that B would

remain zero in the interior. What Meissner showed is

that the state with the flux excluded is the unique

thermodynamically stable state of a superconductor.

Thus the currents flowing near the surface that coun-

teract the external field are stable, not metastable.

Early attempts to account for the vanishing resist-

ance were aimed at trying to understand why the

electrons making up the supercurrent flow are not

scattered as they are in the normal state. After the

discovery of the Meissner effect, the focus shifted

to the nature of the phase transition in the elec-

tronic structure that could lead to such remarkable

properties.

Superconductivity can be understood only in terms

of quantum theory; superconductors are quantum

systems on a macroscopic scale. The current flowing

around a superconducting ring is quantized such that

the total magnetic flux threading the ring is an inte-

gral multiple of a flux unit, F

0

¼ h=2e ¼ 2:07

10

15

Wb.

There is a critical magnetic field as well as a critical

temperature. Because flux is excluded from the inte-

rior, there is an increase in magnetic energy of

1

2

m

0

H

2

per unit volume, where H is the applied field. When

this magnetic energy more than makes up for the free

energy differences G

s

(0)–G

n

between superconducting

and normal phases in the absence of a field, the sys-

tem reverts to normal. Thus the critical magnetic field

H

c

is given by

1

2

m

0

H

2

c

¼ G

n

G

s

ð0Þð1Þ

The free energy difference and critical fields decrease

with increasing temperature and vanish at the critical

temperature T

c

. There is an approximate law of cor-

responding states:

H

c

¼ H

0

ð1 ðT=T

c

Þ

2

Þð2Þ

where H

0

is the critical field at T ¼0 K. Equation (1)

gives a relation between H

c

(T) and the thermody-

namic quantities, such as heat capacity, that can be

derived from the free energy. Experiments in the early

1930s by Keesom and co-workers at Leiden verified

these relations experimentally.

In 1934, Gorter and Casimir showed that Eqn. (2)

and other properties could be accounted for by a

phenomenological two-fluid model in which there is

an electron charge density r

s

ðr

s

¼ n

s

eÞ associated

with the superfluid condensate and a density r

n

as-

sociated with electrons excited out of the condensate

and subject to the usual scattering processes, with the

total density r ¼ r

s

þ r

n

. The total current is then

J ¼ r

s

v

s

þ r

n

v

n

, where v

s

and v

n

are the velocities of

the two components. In the absence of an electric

field, v

n

¼0 and J

s

¼ r

s

v

s

. There is no entropy asso-

ciated with r

s

, so a supercurrent carries no entropy.

A little later, in 1935, F. London and H. London

proposed their famous phenomenological equations

to describe the electrodynamics of superconductors.

To account for infinite conductivity and the Meissner

effect, they added to Maxwell’s equations an equa-

tion relating the current to magnetic field:

J

s

ðrÞ¼AðrÞ=L ð3Þ

where L ¼ m=n

s

e

2

m

0

and A is the vector potential

expressed in a gauge such that r:A ¼ 0. The time

derivative gives the usual equation for acceleration

of the electron in an electric field in the absence of

dissipation. Equation (3) leads in addition to the

Meissner effect.

F. London suggested that superconductivity is a

quantum phenomenon associated with the rigidity of

the wave function describing the response of the

system to changes of the momentum p of electrons in

a magnetic field. The current is given by a sum over

all electrons of e/p eAS=m averaged over the

wave function of the superconducting condensate.

1147

Superconducting Materials: BCS and Phenomenological Theories

Equation (3) follows if /pS ¼ 0 even in the presence

of a magnetic field (described in the London gauge).

In a normal metal /pS changes in such a way that

/p eAS is very small, giving just the small Landau

diamagnetism. Particularly in his book, published in

1950, London emphasized that the rigidity of the

wave functions in a magnetic field could arise from a

long-range order in the momentum distribution of

the electrons.

According to the London theory, the shielding

currents near the surface of a superconductor in a

magnetic field flow in a layer of average thickness

determined by a penetration depth l ¼ l

L

¼ L

1=2

,

determined by n

s

, the density of superconducting

electrons. In the late 1940s, Pippard, working at

Cambridge, found that the penetration depth in-

creases markedly with added impurities. Impurities

decrease the scattering mean free path of electrons in

the normal state but have little effect on their density.

For this and other reasons, he proposed a nonlocal

form of the London relation in Eqn. (3) in which

J

s

ðrÞ is given by an integral of AðrÞ over a region

surrounding the point r of size determined by a co-

herence distance x.Ifl is the electron mean free path,

x

1

¼ x

1

0

þ l

1

ð4Þ

where x

0

is the coherence distance in the pure metal,

typically of order 10

7

m.

About the same time (1950), Ginzburg and Landau

proposed a different sort of modification of the Lon-

don equations. They were interested in trying to un-

derstand the energy of the boundary between

superconducting and normal domains in the inter-

mediate state. The intermediate state consists of a

series of normal and superconducting domains in the

form of slabs parallel to the applied field. The field B

is equal to the critical field in the normal domains and

vanishes in the interior of the superconducting do-

mains. The change from n

s

¼0 in the normal domains

to the equilibrium value in the superconducting do-

mains occurs gradually across the boundary over a

distance determined by the two lengths in the prob-

lem, x and l.

Thus they needed to have a theory that describes

changes of n

s

(r) in space. Further, in accord with

Landau’s theory of second-order phase transitions,

they described the ordered low-temperature phase by

an order parameter that vanishes as T-T

c

. Ginzburg

and Landau showed remarkable insight in proposing

on phenomenological grounds that the order para-

meter be a complex function CðrÞ¼jCðrÞjexp½i jðrÞ

with amplitude and phase. The order parameter

describes both the density n

s

and the velocity v

s

of

superconducting condensate:

n

s

¼jCðrÞj

2

m

v

s

¼ _rjðrÞe

AðrÞ

)

ð5Þ

Because of pairing, it is now known that m

¼ 2 m,

e

¼ 2e and n

s

¼ n

s

=2.

Since CðrÞ must be single valued, the line integral

of rj around a closed loop must be a multiple of 2p.

If the loop is in the interior of a superconductor

where v

s

¼0 (such as around the interior of a torus

containing a persistent current), the enclosed flux F ¼

H

A:dl ¼ðh=e

Þ

H

rjdl must be a multiple of a flux

unit F

0

¼ h=e

.

By expanding the free energy in powers of C(r),

they derived a nonlinear Schro

¨

dinger-like equation to

determine C(r). This equation was coupled with

Maxwell’s equations to determine C(r) and thus the

supercurrent flow subject to appropriate boundary

conditions. The expansion is presumed to be valid

just below T

c

where C(r) is small. They used the

equations to determine the boundary energy as well

as other properties of superconductors.

To have a Meissner effect, the boundary energy

must be larger than a critical value. Otherwise the

superconductor could break up into a structure with

very thin normal regions that would allow the flux

to penetrate a distance l on either side. The decrease

in magnetic energy from the flux penetration would

more than compensate for the higher free energy of

the normal regions. Ginzburg and Landau found

that the criterion could be described by a parameter

k ¼ l=x.Ifko1=O2, the superconductor is stable

against normal domain formation for all fields less

than H

c

and there is a perfect Meissner effect.

If k41=O2, the flux begins to penetrate when the

field is greater than a lower critical field H

c1

oH

c

, but

the metal remains superconducting up to a higher

critical field, H

c2

4H

c

. Since magnetic flux can

penetrate for H

c1

oHoH

c2

, the increase in magne-

tic energy is less than that for a complete Meissner

effect, so that the transition to the normal state does

not occur until the higher critical field is reached. The

upper critical field H

c2

may be as large as 20 T

or greater for some intermetallic compounds. High-

field superconducting magnet wire is made with such

materials.

Superconductors with ko1=O2 that exhibit a per-

fect Meissner effect are called type I, those with

k41=O2 are called type II. Type-II superconductors

were first investigated by Shubnikov at Kharkov in

the Soviet Union in 1937 and 1938. His work stopped

when he fell victim to a purge.

It was first thought that flux penetrates type-II su-

perconductors through thin layers of normal domains

as it does in the intermediate state. Then Abrikosov

derived another solution, published in 1957, of the

Ginzburg–Landau equations that he interpreted as a

periodic array of quantized vortex lines. The order

parameter C(r) goes to zero on the axis of the lines.

Supercurrent circulating around the axis gives rise

to one unit of flux F

0

. With this theory, Abrikosov

was able to account in a quantitative way for the

magnetization curves observed by Shubnikov.

1148

Superconducting Materials: BCS and Phenomenological Theories

In addition to the Ginzburg–Landau theory, the

year 1950 was notable for the experimental discovery

that T

c

depends on isotopic mass (indicating that the

motion of the ions in the metal must be involved) and

H. Fro

¨

hlich’s independent suggestion that interac-

tions between electrons and lattice vibrations (or their

quanta, phonons) are responsible for superconduc-

tivity. Results of the experiments could be accounted

for if T

c

varies inversely with the square root of the

isotopic mass.

Onnes just missed discovering the isotope effect 30

years earlier. He attempted to detect a difference in

critical temperature between ordinary lead and lead

that came from radioactive decay of uranium. How-

ever, his measurements were not sufficiently precise

to find the small difference in T

c

arising from the

slight difference in mass of the lead nuclei from the

two sources.

Attempts by Fro

¨

hlich and by Bardeen in 1950 to

explain superconductivity in terms of changes in the

energy of individual electrons from interaction with

the phonons failed. Pines and Bardeen showed that the

electron–phonon interaction leads to an effective at-

tractive interaction for electrons which have energies

within a phonon energy of the Fermi energy E

F

.Itwas

thought that it would be necessary to take this attrac-

tive interaction into account in a successful theory.

2. Pairing Theory of Superconductivity

In 1957, Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer gave a the-

ory of superconductivity based on pairing of elec-

trons in the superconducting ground state. Pairing

occurs in such a way as to take advantage of the

attractive phonon-induced interaction between elec-

trons. An energy gap for quasiparticle excitations

appears at the Fermi surface, in confirmation of ex-

periments in the early 1950s of heat capacity and of

thermal conductivity. The theory, known as the BCS

theory from the initials of the authors, has been suc-

cessful in accounting in quantitative detail for a wide

variety of properties of superconductors, including

the isotope effect, the Meissner effect, persistent cur-

rents, a second-order phase transition, an expression

for the supercurrent in the form suggested by Pip-

pard, penetration depths and their temperature de-

pendence, and other electromagnetic and thermal

properties.

Normal metals are well described by a Fermi sea of

electrons and quasiparticle excitations of electrons

from the sea. Each quasiparticle state is defined by a

wave vector k and spin s.AtT ¼0 K, all states with

energies less than the Fermi energy E

F

are occupied;

those above are unoccupied. Low-lying excited con-

figurations can be described by the wave vectors of

the occupied states above E

F

and unoccupied states

or holes below E

F

. If the energy x

k

is measured

from the Fermi energy, the total excitation energy is

given by

W

exc

¼

X

occ

k4k

F

x

k

þ

X

occ

kok

F

jx

k

jð6Þ

Self-energies from effects of coulomb and phonon in-

teractions are included in the quasiparticle energies x

k

.

According to BCS, the ground-state wave function

of the superconducting condensate is a linear com-

bination of a selected set of wave functions C

i

of low-

lying excited configurations of the normal metal:

C

s

¼

X

a

i

C

i

ð7Þ

The configurations C

i

which enter the sum are

restricted to those in which the normal quasiparticle

states are occupied in pairs of opposite spin and

momentum ðkm; kkÞ, such that if in a given config-

uration one of the two states is occupied, the other is

also. An interaction between electrons gives matrix

elements between two configurations in which a pair

k ðkm; kkÞ is occupied and the pair k

0

unoccupied

in one configuration and k

0

occupied and k

unoccupied in the other. With paired configurations,

the phases of the wave functions can be chosen so

that all matrix elements between such configurations

are negative for an attractive interaction V. If the

coefficients a

i

have the same sign or phase, the matrix

elements V

ij

add coherently to give a negative con-

tribution to the energy:

Z

C

s

VC

s

dt ¼

X

a

i

a

j

V

ij

ð8Þ

The wave function in Eqn. (7) was written by BCS

in terms of creation operators, c

ks

for putting a par-

ticle in the state k, s:

C

s

¼

Y

k

ðu

k

þ v

k

c

km

c

kk

ÞC

0

¼

X

N

a

N

c

N

ð9Þ

Here v

2

k

is the probability that the pair ðkm; kkÞ is

occupied and u

2

k

¼ 1 v

2

k

is the probability that it is

unoccupied. The wave function is not an eigenstate of

the number of pairs N, but the coefficients u

k

and v

k

can

be chosen so that the distribution is sharply peaked

about the number in the normal ground state below E

F

.

For a simple model in which it is assumed that

V

ij

¼V for jx

k

jo_o

ph

and zero otherwise, where

_o

ph

is an average phonon energy, the following re-

sults are obtained by a variational method:

u

2

k

¼ 1 v

2

k

¼

1

2

1 þ

x

k

E

k

ð10aÞ

E

k

¼ðx

2

k

þ D

2

Þ

1=2

for jx

k

jo_o

ph

ð10bÞ

D ¼ 2_o

ph

exp½1=Nð0ÞVð10cÞ

G

s

G

N

¼

1

2

Nð0ÞD

2

ð10dÞ

1149

Superconducting Materials: BCS and Phenomenological Theories