Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

with magnetic markers or magnetic nanoparticles

have also contributed to biomagnetic research. The

magnetic fields under investigation in biomagnetism

are very weak. Signal amplitudes that are typically

measured are in the range 10

9

–10

14

T in a fre-

quency range from d.c. to 1 kHz. This requires the

sensitivity to magnetic fields that only SQUIDs pro-

vide. In addition, very efficient methods for suppress-

ing electric and magnetic interference have to be used.

Modern biomagnetic systems are very complex.

With only a few exceptions they are operated in a

magnetically shielded room and contain up to 300

low-T

c

SQUID sensors maintained at liquid helium

temperatures in nonmagnetic fiberglass-reinforced

epoxy dewars. Data acquisition, computation, and

visualization of results require state-of-the-art infor-

mation technology. High-T

c

SQUIDs and liquid ni-

trogen cooling are a future prospect and could reduce

system complexity and costs.

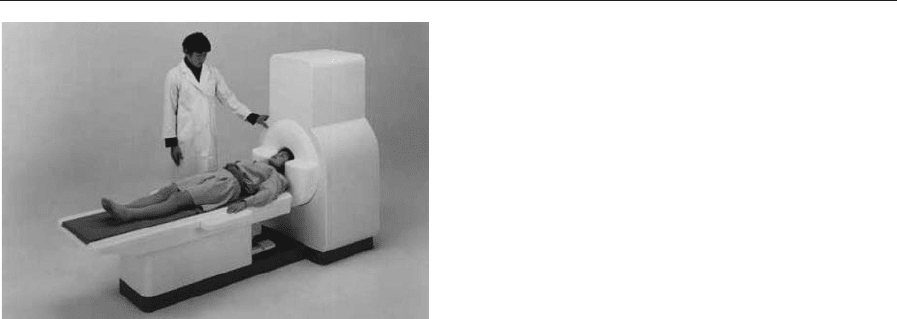

Figure 1 shows a typical system for magnetoencep-

halographic investigations. The patient’s head is po-

sitioned in a helmet-shaped dewar with SQUID

sensors fixed inside at the dewar wall in the vicinity

of the head.

This article introduces several typical applications.

Because of space limitations, only a few instructive

examples of biomagnetic applications are covered

here to demonstrate the broad spectrum of benefits

of biomagnetic SQUID systems. More detailed

overviews can be found elsewhere (e.g., Baum-

gartner et al. 1995, Weinstock 1996, Wikswo 1995).

1. Gastroenterology

From the physical and analytical point of view, this

application is the simplest to handle. The source to be

detected is a small magnetic sample, which may be

easily modeled as a magnetic dipole with well-known

specifications. Thus, if this magnetized sample is pre-

pared and coated in an appropriate manner such that

it can be administered without harm, then its passage

through the gastrointestinal tract of a person may be

monitored with a SQUID system provided with an

algorithm to reconstruct the path of the pellet from

field measurement results. Weitschies et al. (1997)

provide further details of this method.

2. Peripheral Nerves

Another biomagnetic application that relies on a

comparatively simple modeling of the source is the

investigation of peripheral nerve function. The signal

transmission through the nerve fiber may be modeled

as an extended current segment, i.e., by a multipole

expansion. If the spatiotemporal magnetic field dis-

tribution over the nerve is measured with a multi-

channel SQUID system, then the reconstruction of

the current path may be well approximated.

In practice, difficulties result from the poor signal-

to-noise ratio commonly accompanying these exper-

iments. Even with the most sensitive SQUID systems

available an averaging of up to 10

4

stimuli is neces-

sary to recover the relevant magnetic field signal from

the noise. Particularly, the heart signal interferes

strongly and has to be eliminated by advanced meth-

ods of signal processing. Nevertheless, Mackert et al.

(1998) have been able to detect the blocking of nerve

signal transmission.

3. Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

MEG is the most successful application of biomag-

netic systems from the scientific and the commercial

point of view. In 1998 more than 50 multichannel

SQUID systems were installed and used for MEG

investigations worldwide. The latest system genera-

tion contains more than 300 SQUID channels.

Most applications concern fundamental physiolog-

ical and psychological brain research. Clinical appli-

cations concern preoperative evaluation and mapping

of brain functions and localization of epileptic foci of

patients suffering from epilepsy. For an overview on

various aspects of MEG see Lounasma et al. (1996).

Technologically demanding is the construction of

a nonmagnetic helmet-shaped dewar with a close

warm/cold distance between the scalp and the pick-

up coils of the SQUID. Another difficulty is to

provide a spatially high density of sensor positions

without signal cross-talk between the channels.

While all MEG SQUID systems are made using

low-T

c

technology, there is hope that high-T

c

tech-

nology should overcome many of the problems men-

tioned above. The field sensitivity of high-T

c

SQUID

systems has already proved sufficient for brain re-

search. Somatosensory-evoked cortical fields have

Figure 1

SQUID system for magnetoencephalographic

investigations.

1110

SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications

been detected with a high- T

c

SQUID (Drung et al.

1996) having a white noise of o10 fTHz

1/2

.

4. Magnetocardiography (MCG)

Although the maximum amplitude of MCG signals is

1–2 orders of magnitudes higher than typical MEG

signals it is necessary to achieve a similarly good sig-

nal-to-noise ratio, as the relevant signal components

may be of comparably small amplitude. Clinically

interesting applications are seen in the field of risk

stratification of sudden heart death and myocardial

vitality.

One way to derive relevant information from mag-

netic field maps is to recognize specific patterns or

features in the field maps that can be considered as a

‘‘fingerprint’’ or ‘‘signature’’ of certain physiological

or pathophysiological functions in which the physi-

cian is interested and wants to discriminate. A com-

mon approach is then to quantify these signatures by

derived characteristic factors. For instance, patients

who suffer from coronary artery heart disease, and

thus have a high risk of a sudden heart death, show

distinctive alterations in magnetic field maps com-

pared to those of normal subjects. The factors men-

tioned above reflect these alterations and give a

valuable indication as to this risk.

5. Source Localization

Many applications demand a ‘‘localization’’ of the

physiological or pathophysiological function looked

for. Technically, this requires a reconstruction of the

current density distribution, the ‘‘source,’’ that gen-

erated the measured magnetic field pattern. Mathe-

matically, this inverse problem, i.e., the calculation of

the source distribution with the help of measured field

values, is a so-called ill-posed problem, because prin-

cipally no unique solution exists. However, with the

aid of appropriate models an acceptable approxima-

tion of the source may be derived. The most common

model is the equivalent current dipole, which is of

good value in mapping localized brain functions such

as evoked cognitive responses.

A more sophisticated algorithm (Fuchs et al. 1995

pp. 320–5) models the current density distribution of

the investigated brain or heart function by many

small current dipoles distributed over the cortex or

the heart ventricle only at such positions that come

into question on physiological grounds. In this way,

the possible solutions of the inverse problem are ef-

fectively constrained. The proper anatomic geometry

is derived from magnetic resonance imaging.

6. Towards Unsh ielded SQUID Systems

In order to suppress noise due to magnetic fields

generated, for example, from power line hum, electric

street cars, etc., biomagnetic systems are commonly

operated in shielded rooms with thick walls consist-

ing of several layers of mu-metal. Such shielded

rooms make SQUID systems very expensive and

prohibit a wider distribution of biomagnetic meth-

ods. Therefore, many approaches have been tried to

reduce the need for passive shielding.

One way is to use gradiometer concepts, i.e., in-

stead of measuring with one magnetometer the mag-

netic flux at one position, one determines the

difference of magnetic flux of two adjacent positions

(i.e., the approximation of the gradient of the mag-

netic field). As the source to be investigated is close to

the sensors it provides a strong gradient as compared

to a distant interfering source and thus the source

signals are enhanced with respect to the interference.

Gradiometric configurations may be achieved with

appropriately formed pick-up coils: vertical or planar

gradiometers. Another way is to use two magneto-

meters and subtract their signals from each other

electronically, thus forming ‘‘electronic’’ gradiome-

ters. Similarly ‘‘software’’ gradiometers may be

designed.

A modern solution is to configure the SQUIDs to

form a reference system that provides all signal in-

formation for a sophisticated algorithm, which then

generates the appropriate compensation signals to

each of the SQUIDs in the measurement plane of a

multichannel system. At sites with only moderate in-

terference, such systems have successfully demon-

strated an unshielded performance. However, in

urban or clinical environments a passive shield may

still be necessary. For a detailed analysis of the topic

of interference discrimination see Vrba (1996 pp.

117–78).

With HTS SQUIDs unshielded operation is even

more difficult owing to the sensitivity to trapped and

moving flux lines in the high-T

c

material, particularly

if the sensors are cooled and moved in the earth’s

magnetic field.

See also: SQUIDs: The Instrument; SQUIDs: Non-

destructive Testing

Bibliography

Baumgartner C, Deecke L, Stroink G, Williamson S J (eds.)

1995 Biomagnetism: Fundamental Research and Clinical Ap-

plications. IOS, Amsterdam

Drung D, Ludwig F, Mu

¨

ller W, Steinhoff U, Trahms L, Koch

H, Shen Y Q, Jensen M B, Vase P, Holst T, Freltoft T, Curio

G 1996 Integrated YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

magnetometer for biomag-

netic measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 1421–3

Fuchs M, Wagner M, Wischmann H -A, Do

¨

ssel O 1995 Cor-

tical current imaging by morphologically constrained recon-

structions. In: Baumgartner C, Deecke L, Stroink G,

Williamson S J (eds.) Biomagnetism: Fundamental Research

and Clinical Applications. IOS, Amsterdam

1111

SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications

Lounasma O V, Ha

¨

ma

¨

la

¨

inen M, Hari R, Salmelin R 1996 In-

formation processing in the human brain: magnetoencepha-

lographic approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8809–15

Mackert B M, Curio G, Burghoff M, Trahms L, Marx P 1998

Magnetoneurographic 3D localisation of conduction blocks

in patients with unilateral S1 root compression. Elect-

roenceph. Clin. Neurophys. 109, 315–20

Vrba J 1996 SQUID gradiometers in real environments. In:

Weinstock H (ed.) SQUID Sensors: Fundamentals, Fabrica-

tion and Applications, NATO ASI Series E, Applied Science

329. Kluwer, Amsterdam

Weinstock H (ed.) 1996 SQUID Sensors: Fundamentals, Fab-

rication and Applications, NATO ASI Series E, Applied Sci-

ence 329. Kluwer, Amsterdam

Weitschies W, Ko

¨

titz R, Cordini D, Trahms L 1997 High-res-

olution monitoring of the gastrointestinal transit of a mag-

netically marked capsule. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 66, 1218–22

Wikswo J P 1995 SQUID magnetometers for biomagnetism

and nondestructive testing: important questions and initial

answers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 5, 74–120

H. Koch

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt

Berlin, Germany

SQUIDs: Magnetic Microscopy

Magnetic fields above sample surfaces can be imaged

using a superconducting quantum interference device

(SQUID) in a scanning SQUID microscope (SSM).

Both low critical temperature (low T

c

) SQUIDs

(which have better sensitivity) and high T

c

SQUIDs

(which can be operated at higher temperatures)

(Koelle et al. 1999) have been used as SSM sensors.

The best low T

c

SQUIDs have a flux noise of

B2 10

6

F

0

Hz

1/2

, where F

0

¼h/2e ¼2.07 10

15

Wb is the superconducting magnetic flux quantum.

A SQUID magnetometer with this noise and a

100 mm

2

pickup area can detect magnetic fields of

B40pTHz

1/2

, a dipole source of B2500 m

B

Hz

1/2

,a

monopole source (e.g., a superconducting vortex) of

B2.5 10

6

F

0

Hz

1/2

, and a current line source of

B1 nAHz

1/2

. Smaller pickup areas are more sensitive

for a dipole field source, while larger pickup areas are

more sensitive for a current line source. The spatial

resolution is about the size of the effective area, if the

source–pickup area spacing is smaller than this size.

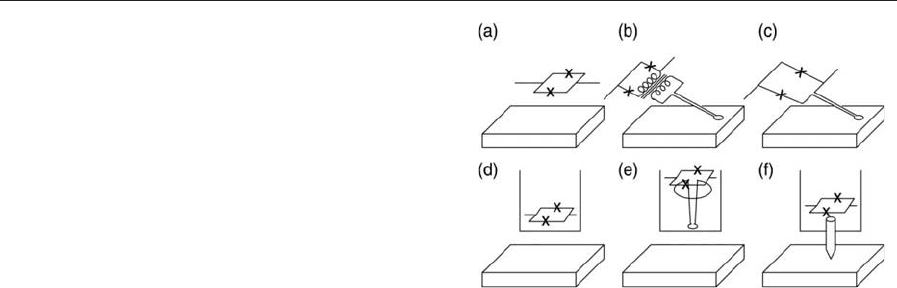

Many schemes have been used to scan the sample

and couple magnetic fields into the SQUID (Kirtley

and Wikswo 1999). Either (i) both sample and

SQUID are cold (Figs. 1(a)–(c)), or (ii) the SQUID

is cold but the sample is at room temperature

(Figs. 1(d)–(f)). The second method has the advan-

tage of not requiring sample cooling, with some

sacrifice in spatial resolution. In either case, a bare

SQUID (Figs. 1(a) and (d)), a SQUID inductively

coupled with a superconducting pickup loop

(Figs. 1(b) and (e)), or a superconducting pickup

loop integrated into the SQUID design (Fig. 1(c))

can be used to detect the sample magnetic field. In

Fig. 1(f), a ferromagnetic tip is used to couple flux

from a room temperature sample to a cooled SQUID.

While early systems connected discrete SQUIDs to

hand-wound pickup coils, integrated SQUID sensors

are now commonplace. In these devices, commonly

Nb–AlO

x

–Nb thin-film SQUIDs, the SQUID junc-

tions, shunt resistors, and modulation coil are

connected to the pickup coil through a well-shielded,

low-inductance lead structure. Pickup loop sizes as

small as 4 mm in diameter have been fabricated: mode-

ling indicates that pickup areas as small as 1 mm

2

can

be effectively attained. SQUIDs using microbridges

as the Josephson weak links (micro-SQUIDs)

(Wernsdorfer et al. 1996) have been fabricated as

small as 1 mm in diameter. These micro-SQUIDs have

two orders of magnitude higher flux noise than the

best tunnel junction SQUIDs, but can be operated in

higher ambient magnetic fields. Most SSMs scan the

sample relative to the SQUID mechanically. While not

as stiff or as fast as piezoelectric scanners, mechanical

scanning affords much larger scan areas (B1cm as

compared to B100 mm).

SSMs have been used in a number of applica-

tions in the fields of biomagnetism, corrosion science,

nondestructive evaluation, and superconductivity

(Wikswo 1995). Two applications in this last area

will be briefly described here.

Exploration of novel superconductors often results

in samples with small superconducting concentra-

tions. The SSM is an ideal tool to image samples to

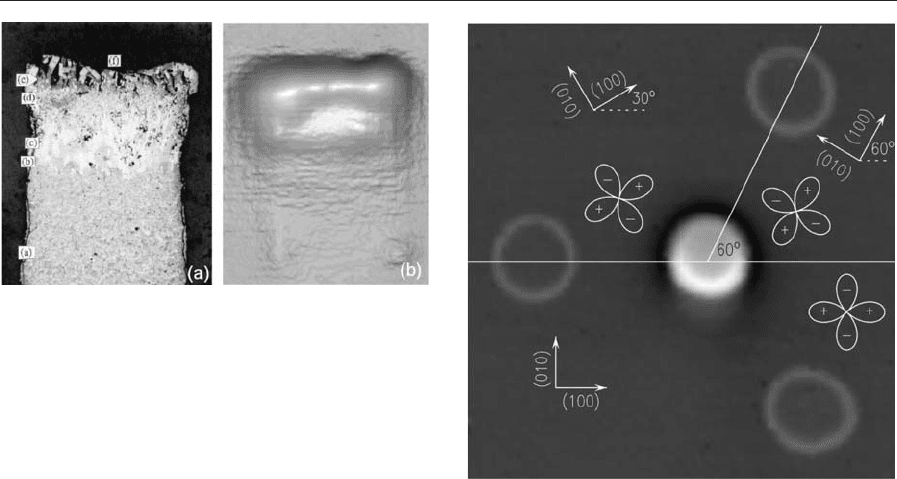

determine which parts are superconducting. Figure 2

shows an example (Scott et al. 1997). Comparison of

optical (Fig. 2(a)) and SSM (Fig. 2(b)) images of a

diffusion couple of Sr

2

CuO

3

þ0.05 KClO

3

processed

at high temperatures and pressures shows that certain

regions (the dark gray areas labeled (e) in Fig. 2(a))

are superconducting. These regions are determined

by electron microprobe to be Sr

3

Cu

2

O

5

Cl.

Figure 1

Various strategies for scanning the sample relative to the

SQUID.

1112

SQUIDs: Magnetic Microscopy

The SSM has also played a central role in phase-

sensitive tests of the pairing symmetry of the high T

c

cuprate superconductors. While conventional super-

conductors have symmetric or s-wave pairing, there is

now good evidence that several optimally doped

cuprates have predominantly d

x

2

y

2 symmetry (see

the polar plots in Fig. 3) (Scalapino 1995). With such

momentum-dependent sign changes, SQUIDs can be

designed with junction supercurrents that destruc-

tively interfere at zero applied field, rather than con-

structively interfering, as for conventional SQUIDs.

The first phase-sensitive tests measured the interfer-

ence patterns of such specially constructed SQUIDs

(van Harlingen 1995).

Other phase-sensitive tests have employed the SSM

(Tsuei et al. 1994, Mathai et al. 1995). Figure 3 is a

SSM image of four thin-film, 58 mm diameter rings of

the high T

c

cuprate superconductor YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

(YBCO) epitaxially grown on a tricrystal substrate of

SrTiO

3

. The tricrystal geometry produces a high-en-

ergy, frustrated state for a d-wave superconductor.

This frustrated state is relaxed by spontaneously gen-

erating a supercurrent around the ring, which pro-

duces a half-integer multiple of the superconducting

flux quantum ((n þ1/2)F

0

, where n is an integer)

threading the ring. The SQUID image of Fig. 3 is of

the sample cooled in zero field. The three outer con-

trol rings have no flux trapped in them; the central

frustrated ring has F

0

/2. A number of optimally

doped cuprate high T

c

superconductors exhibit the

half-flux quantum effect in this geometry, and there-

fore presumably have predominantly d-wave pairing

symmetry.

In summary, magnetic microscopy with SQUIDs

has the advantage of high sensitivity, but the disad-

vantages of the requirement of a cooled sensor and

relatively modest spatial resolution. Progress is being

made in improved instruments with warmed samples,

and with higher spatial resolution.

See also: SQUIDs: The Instrument; Magnetic Force

Microscopy; Magnetic Materials: Transmission Elec-

tron Microscopy; Kerr Microscopy

Bibliography

Kirtley J R, Wikswo J P Jr. 1999 Scanning SQUID microscopy.

Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 29, 117–48

Koelle D, Kleiner R, Ludwig F, Dantsker E, Clarke J 1999

High transition temperature superconducting quantum

interference devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 631–86

Mathai A, Gim Y, Black R C, Amar A, Wellstood F C 1995

Experimental proof of a time-reversal-invariant order

parameter with a p shift in YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

. Phys. Rev. Lett.

74, 4523–6

Scalapino D J 1995 The case for d

x

2

y

2 pairing in the cuprate

superconductors. Phys. Rep. 250, 329–65

Scott B A, Kirtley J R, Walker D, Chen B H, Wang H 1997

Application of scanning SQUID petrology to high-pressure

materials science. Nature 389, 164–7

Tsuei C C, Kirtley J R, Chi C C, Yu-Jahnes L S, Gupta A,

Shaw T, Sun J Z, Ketchen M B 1994 Pairing symmetry and

flux quantization in a tricrystal superconducting ring of

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 593–6

van Harlingen D J 1995 Phase-sensitive tests of the symmetry of

the pairing state in the high-temperature superconductors—

evidence for d

x

2

y

2 symmetry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 67, 515–35

Wernsdorfer W, Doudin B, Mailly C, Hasselbach K, Benoit A,

Meier J, Ansermet J-Ph, Barbara B 1996 Nucleation of the

Figure 3

SQUID microscope image of thin-film YBCO rings. The

presence of a half-flux quantum in the central ring

indicates that YBCO has predominantly d-wave pairing

symmetry (after Tsuei et al. 1994).

Figure 2

(a) Optical micrograph and (b) SQUID microscope

image of a partially superconducting sample. The bright

areas in (b) are superconducting (after Scott et al. 1997).

1113

SQUIDs: Magnetic Microscopy

magnetization reversal in individual nanosized nickel wires.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1873–6

Wikswo J P Jr. 1995 SQUID magnetometers for biomagnetism

and nondestructive testing: important questions and initial

answers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 5, 74–121

J. R. Kirtley

IBM Research, Yorktown Heights, New York, USA

SQUIDs: Nondestructive Testing

The need for inspection has been recognized ever since

people began to build machines. Nondestructive eva-

luation (NDE) techniques that can find hidden flaws

are ultrasonics, radiography, and electromagnetic

techniques (see Nondestructive Testing and Evalua-

tion: Overview). Commonly used magnetic field sen-

sors in NDE are induction coils, Hall probes, and

magnetoresistors. Induction coils are versatile; how-

ever, they have the inherent disadvantage of measur-

ing only the time derivative of the magnetic field. This

requires high signal frequencies for good perform-

ance. Following the development of SQUID sensors,

many research groups have shown the use of SQUIDs

(see SQUIDs: The Instrument) in conjunction with

electromagnetic NDE (e.g., see reviews by Donaldson

et al. 1996, Jenks et al. 1997). The advantages of

SQUIDs include high field sensitivity, wide band-

width, and, possibly most important, very broad dy-

namic range in conjunction with excellent linearity.

1. Eddy Current Inspection

Eddy current testing by inductive sensors is an im-

portant NDE technique, especially for layered struc-

tures. The penetration depth of the electromagnetic

excitation wave, the so-called skin depth, d

0

¼

1/

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

psmf

p

, restricts the depth at which flaws can be

found. For a plane wave excitation with frequency f

of a medium with conductivity s and permeability m,

d

0

denotes the depth of material where the amplitude

is attenuated by 1/e and the phase is rotated by p.

Thus, the phase lag of the response signal contains

information about the flaw depth. In contrast to

conventional techniques, SQUID systems offer a high

sensitivity at low excitation frequencies, permitting

the detection of deeper flaws, and a high linearity,

allowing quantitative evaluation of magnetic field

maps from the structure investigated. Several re-

search groups have developed LTS as well as HTS

SQUID systems for eddy current testing (e.g., Ma

and Wikswo 1993, Podney 1995, Tavrin et al. 1996,

Cochran et al. 1995).

Nondestructive testing (NDT) of new and aging

aircraft structures is essential for flight safety and for

keeping inspection costs low. Eddy current testing is a

widely used NDT method in aircraft maintenance.

The applicability of HTS SQUID magnetometers to

aircraft testing has been demonstrated by Kreutzb-

ruck et al. (1997). Mobile HTS SQUID planar gra-

diometers with orientation-independent cooling have

been developed for eddy current testing of ‘‘second

layer’’ cracks and corrosion in aircraft fuselages

(Krause et al. 1997).

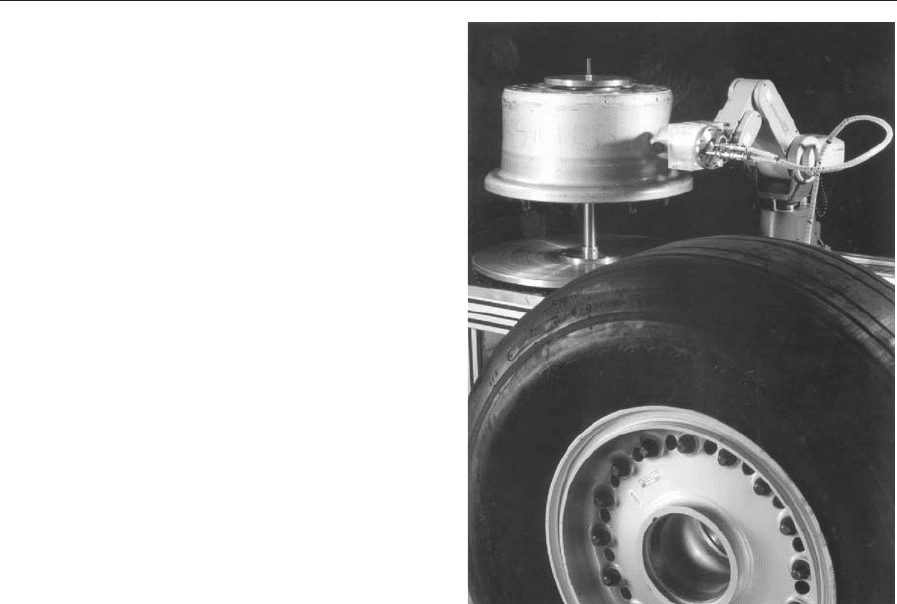

The detection of deep cracks in aircraft wheels is

one example of the application of HTS SQUIDs to

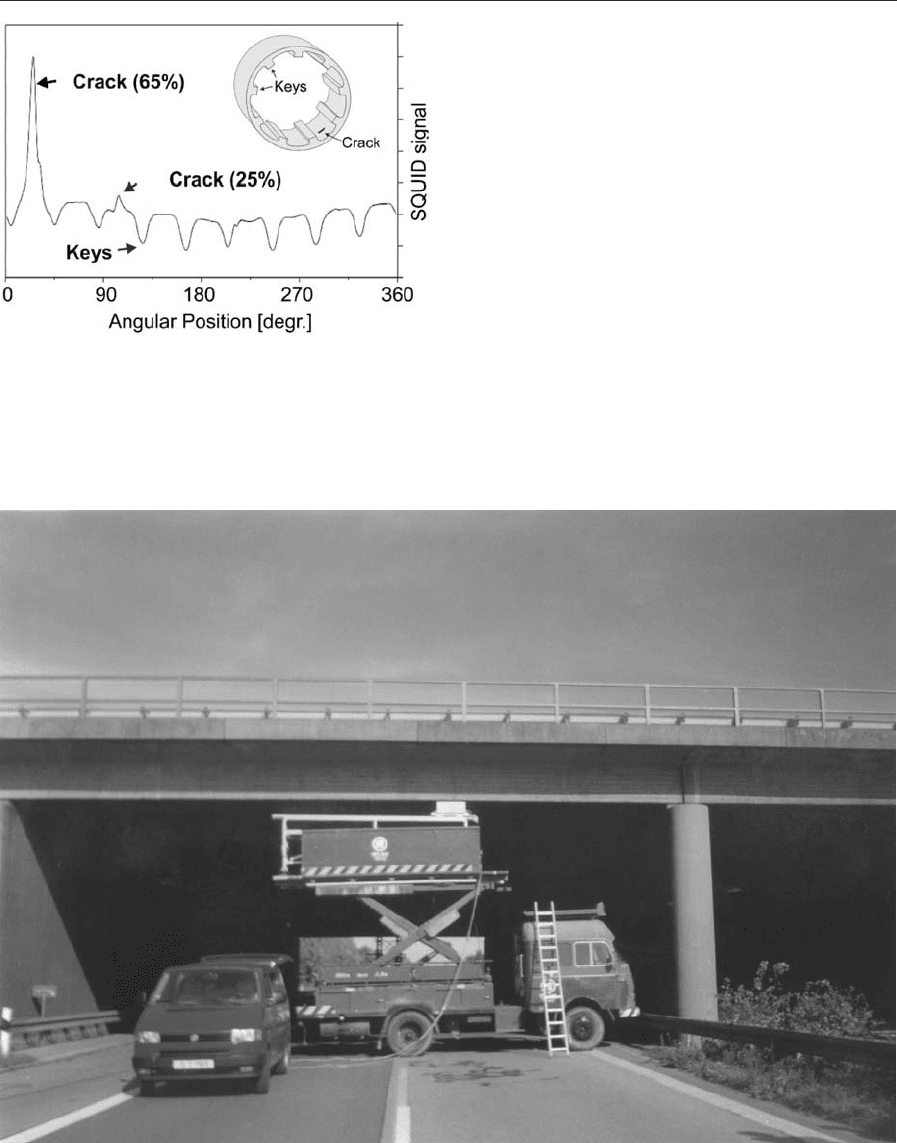

NDT (Hohmann et al. 1999). Figure 1 shows the

main parts of a wheel-testing unit. The system con-

sists of a rotating table, a robot, and a sensor head. A

planar SQUID gradiometer has been integrated with

a commercial Joule–Thomson cryocooler, providing

liquid nitrogen-free SQUID cooling. For the gener-

ation of eddy currents in the sample, a double-D

configuration of induction coils is used. Figure 2

shows the measurement of flaws in an aircraft wheel.

2. Magnetic Flux Leakage

Surface or subsurface flaws in ferromagnetic materi-

als are usually detected by magnetizing the test object

Figure 1

Automated wheel-testing system.

1114

SQUIDs: Nondestructive Testing

and monitoring the magnetic flux leakage (MFL)

above the surface. Open voids lead to a strong en-

hancement of the outside stray field due to the local

absence of a high permeability flux guide. Subsurface

voids affect the local permeability (magnetization) of

the material and, therefore, also the local stray field.

These stray fields are observed either while continu-

ously magnetizing the object or by measuring the re-

manent magnetization. Local changes in the stray

field are mapped by means of scanning the magnetic

field sensor over the metal.

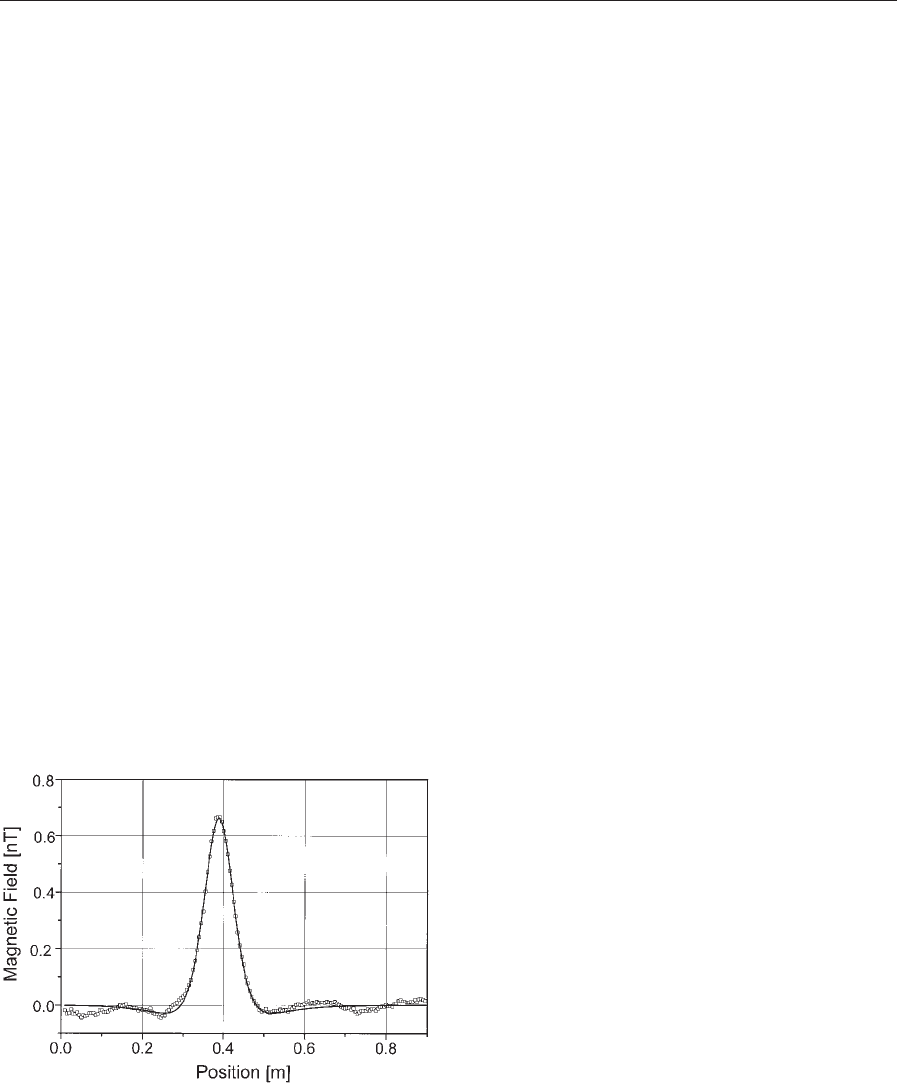

The MFL technique has been used for the detec-

tion of cracks in steel reinforcement rods (rebars) in

concrete structures such as bridges or roofs of build-

ings (Sawade et al. 1997). Owing to hydrogen-in-

duced stress and corrosion, cracks and other damage

to prestressed concrete members can occur. The re-

bars are magnetized longitudinally during a scan with

a yoke magnet. In the center of the yoke, the stray

field is picked up by HTS SQUIDs, having a greater

linearity and dynamic range than conventional Hall

Figure 2

SQUID measurement of an aircraft wheel. Two inner

flaws that penetrate the wall thickness by 65% and 25%

are detected.

Figure 3

Inspection of a German highway bridge using a SQUID system.

1115

SQUIDs: Nondestructive Testing

probe magnetometers, also incorporated into the

same scanner. With this system, dangerous cracks

were detected in a German freeway bridge with run-

ning car traffic (see Fig. 3). Subsequent opening of

the concrete at the detected location confirmed the

findings, and the bridge had to be decommissioned

and demolished.

3. Detection of Ferromagnetic Particles

The first certified commercial use of HTS SQUIDs in

everyday NDE was the detection of ferrous inclusions

in premagnetized aircraft gas turbine disks, fabricat-

ed from a special nonmagnetic alloy. The presence of

such inclusions may cause cracks in these critical

parts, and may eventually lead to engine failure. Ta-

vrin et al. (1999) used a second-order unshielded axial

gradiometer for determination of the mass, radial

position, and depth of small ferromagnetic inclusions

in the disk. The disk is slowly rotated on a turntable

while the gradiometer is moved radially by a me-

chanically stable arm. The measurements of reman-

ent magnetization at two different axial distances

from the disk surface are used to calculate the mag-

netic particle depth using the dipolar 1/R

3

scaling

law. The approximate particle mass is then deter-

mined from its dipole strength. A particle mass of

1 mg is reliably measurable in the depth range up to

70 mm.

Another approach to the problem of ferromagnetic

inclusion detection has been presented by Panaitov

et al. (1999). A SQUID vector reference is used in

a first-order electronic gradiometer to compensate

for the disturbances of unshielded environments.

Samples with small particles of different sizes and

magnetic moments are placed on a scanning table

and moved underneath the gradiometer sensor and

the axial component of the d.c. magnetic field is re-

corded. By fitting the measured field profile to a di-

pole law, the amplitude of the magnetic moment and

the distance from the sensor to the particle is deter-

mined. Figure 4 shows an example of the measured

particle field profile and the dipole fit to the trace.

4. Outlook

Ideally, the end user would like a tomography-like

three-dimensional analysis of the material under test,

an image of the sample. This requires the solution of

the three-dimensional inverse problem: the determi-

nation of the source distribution inside an object by

measuring the magnetic fields at a few locations out-

side (cf. Wikswo 1996). Practical implementation of

these imaging techniques is expected to become avail-

able in the future.

See also: SQUIDs: Biomedical Applications; SQUIDs:

The Instrument

Bibliography

Cochran S, Donaldson G B, Carr C, McKirdy D

McA, Walker M E, Klein U, McNab A, Kuznik J 1995 Re-

cent progress in SQUIDs as sensors for electromagnetic

NDE. In: Collins R, Dover W D, Bowler J R, Miya K (eds.)

NDT of Materials. IOS, Amsterdam, pp. 53–64

Donaldson G B, Cochran A, McKirdy D McA 1996 The use of

SQUIDs for nondestructive evaluation. In: Weinstock H

(ed.) SQUID Sensors. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands,

pp. 599–628

Hohmann R, Maus M, Lomparski D, Gru

¨

neklee M, Zhang Y,

Krause H J, Bousack H, Braginski A I, Heiden C 1999 Air-

craft wheel testing with machine-cooled HTS SQUID gradi-

ometer system. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 9, 3801–4

Jenks W G, Sadeghi S S H, Wikswo J P 1997 SQUIDs for

nondestructive evaluation. J. Phys. D 30, 293–323

Krause H J et al. 1997 Mobile HTS SQUID systems for eddy

current testing of aircraft. In: Thompson D O, Chimenti D E

(eds.) Rev. Prog. QNDE 16. Plenum, New York, pp. 1053–60

Kreutzbruck Mv, Tro

¨

ll J, Mu

¨

ck M, Heiden C 1997 Experi-

ments on eddy current NDE HTS rf SQUIDs. IEEE Trans.

Appl. Supercond. 7, 3279–82

Ma Y P, Wikswo J P 1993 Imaging subsurface defects using a

SQUID magnetometer. In: Thompson D O, Chimenti D E

(eds.) Rev. Prog. QNDE 12. Plenum, New York, pp. 1137–43

Panaitov G, Zhang Y, Wang S G, Wolters N, Zhang L H, Otto

R, Schubert J, Zander W, Soltner H, Bick M, Krause H J,

Bousack H 1999 An HTS SQUID magnetometer using

coplanar resonator with vector reference for operators in

unshielded environment. In: Obradors X (ed.) Applied Su-

perconductivity. Institute of Physics, Bristol, UK, pp. 449–52

Podney W N 1995 Eddy current evaluation of airframes using

refrigerated SQUIDs. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 5,

2490–2

Sawade G, Gampe U, Krause H J 1997 Non-destructive

examination using a SQUID magnetometer. In: Forde M T

Figure 4

Signal of a small magnetic particle, measured with a

SQUID gradiometer (squares). From the dipole fit (line)

the moment of particle is found to be 2.6 10

6

Am

2

,

with a minimum distance to the sensor of 87 mm.

1116

SQUIDs: Nondestructive Testing

(ed.) Proc. 7th Int. Conf. on Structural Faults and Repair.

Engineering Technical Press, Edinburgh, UK, pp. 401–6

Tavrin Y, Krause H J, Wolf W, Glyantsev V, Schubert J,

Zander W, Bousack H 1996 Eddy current technique with

high-temperature SQUID for non-destructive evaluation of

non-magnetic metallic structures. Cryogenics 36, 83–6

Tavrin Y, Siegel M, Hinken J H 1999 Standard method for

detection of magnetic defects in aircraft engine discs using an

HTS SQUID gradiometer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 9,

3809–12

Wikswo J P 1996 The magnetic inverse problem for NDE. In:

Weinstock H (ed.) SQUID Sensors. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The

Netherlands, pp. 629–95

H. Bousack, R. Hohmann, H.-J. Krause

G. Panaitov and Y. Zhang

Forschungszentrum Ju

¨

lich, Germany

SQUIDs: The Instrument

The superconducting quantum interference device

(SQUID) is exquisitely sensitive to tiny changes in

magnetic flux. It can be configured as a very sensitive

magnetometer or magnetic field gradiometer, but it

can also be used in a wide variety of other applica-

tions, for example to measure tiny voltages, to detect

very small magnetic moments, and to amplify radio-

frequency (RF) signals.

There are two basic types of SQUID. The first, the

d.c. SQUID—so called because it operates with a

static bias current—consists of two Josephson junc-

tions (see Josephson Junctions: Low-T

c

and Josephson

Junctions: High-T

c

) connected in parallel on a super-

conducting loop. When the magnetic flux threading

the loop is changed, the maximum supercurrent the

device is able to sustain (the ‘‘critical current’’) oscil-

lates with a period of one flux quantum, F

0

h/2eE2.07 10

15

Wb (see Electrodynamics of Super-

conductors: Flux Properties).

The origin of this effect lies in the flux-induced

changes in the phases of the superconducting order

parameter across the two junctions in a way that is

analogous to the two-slit interference experiment in

optics: hence the acronym SQUID. This effect was

first observed by Jaklevic et al. (1964), and practi-

cal—if somewhat primitive—devices quickly fol-

lowed. By measuring the change in voltage across

the current-biased SQUID, one can detect changes in

magnetic flux corresponding to a minute fraction of a

flux quantum.

The second type of device, the RF SQUID, ap-

peared in 1970, and involves a single Josephson junc-

tion incorporated into a superconducting loop

(Mercereau 1970, Zimmerman et al. 1970). The loop

is inductively coupled to the inductance of a resonant

circuit that is excited at RFs. The RF voltage across

the resonant circuit is periodic in the flux threading

the loop with a period, F

0

, enabling one to detect

changes in flux in much the same way as with the d.c.

SQUID. RF SQUIDs made from machined blocks of

niobium became popular in the early 1970s. Howev-

er, the development of the thin-film d.c. SQUID in

1976 and the subsequent development of techniques

to fabricate thin-film niobium SQUIDs on a wafer

scale using microfabrication techniques borrowed

from the semiconductor industry resulted in the

dominance of this kind of device for low-transition-

temperature (T

c

) superconductors. These devices are

mostly used at liquid helium temperatures (4.2 K) or

lower.

The advent of high-T

c

superconductivity in 1986

led numerous research groups to adopt the SQUID

as a vehicle to develop their thin-film and multilayer

processing technologies. A wide variety of devices

grew from this effort, based on thin films of

YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7x

(YBCO), resulting in a viable device

technology at liquid nitrogen temperatures (77 K).

Although most groups have preferred the d.c.

SQUID, its advantage in sensitivity over the RF

SQUID is less marked than in the case of low-T

c

devices.

This article first outlines the principles of the d.c.

SQUID, and then describes practical low-T

c

devices

and their operation and performance. The principle

of the superconducting flux transformer is intro-

duced, and its use in magnetometers and gradiome-

ters is discussed. The fabrication and performance of

high-T

c

SQUIDs, magnetometers, and gradiometers

are described. The principles, fabrication, operation,

and performance of high-T

c

RF SQUIDs are dis-

cussed, and their application as magnetometers and

gradiometers is described (Barone 1992, Clarke 1996,

Koelle et al. 1999).

1. Low-T

c

d.c. SQUIDs

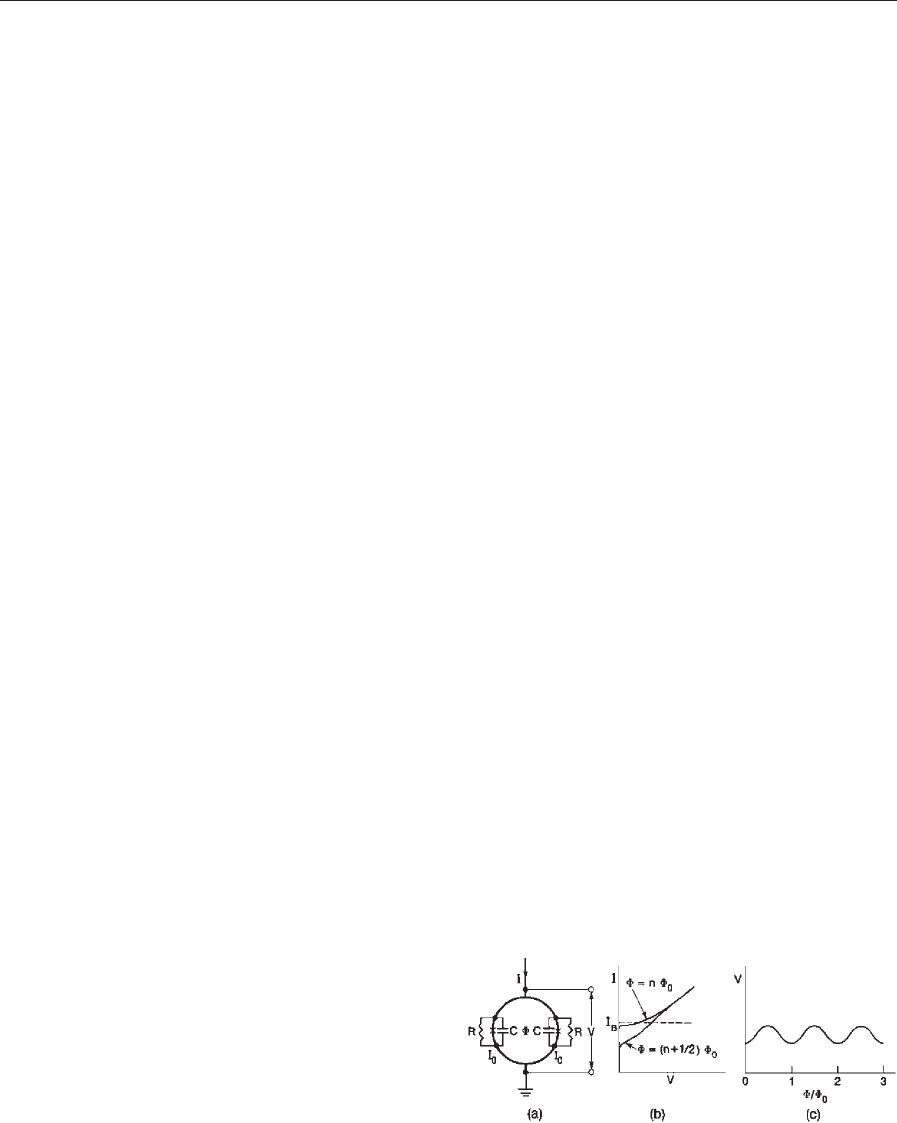

Figure 1(a) shows the configuration of the d.c.

SQUID. Generally, each of the two Josephson junc-

tions is resistively shunted so that the current–voltage

(I–V) characteristic is nonhysteretic, as shown in

Fig. 1(b). As one changes the magnetic flux, F,

threading the loop, the critical current and the I–V

Figure 1

d.c. SQUID: (a) schematic; (b) I–V characteristic; (c) V

vs. F/F

0

at constant bias current I

B

.

1117

SQUIDs: The Instrument

characteristic oscillate between the two extremes

shown with a period, F

0

. Thus, when the SQUID is

biased with a constant current, I

B

, the voltage across

the SQUID is periodic in F, as shown in Fig. 1(c). One

operates the SQUID with the bias current adjusted to

maximize the amplitude of the voltage oscillations,

and the static flux is adjusted to (n7

1

4

)F

0

(n is an in-

teger) to obtain the maximum transfer function,

V

F

7@V/@F7

I

B

.OnemeasuresafluxchangedF5F

0

simply by detecting the resulting change in the voltage.

The behavior of the SQUID can be represented by

a set of nonlinear equations involving the current and

flux biases, the inductance, L, of the SQUID loop, the

critical current, I

0

, shunt resistance, R, and capaci-

tance, C, of the two Josephson junctions, the phase

difference across each junction, the voltage across the

SQUID, and the Nyquist noise generated by each

shunt resistor (Tesche and Clarke 1977). To avoid

hysteresis in the I–V characteristic, the junction pa-

rameters must satisfy the constraint b

c

¼2pI

0

R

2

C/

F

0

t1. There have been extensive computer simula-

tions of these equations in order to obtain parameters

that optimize the performance of the SQUID.

These simulations reveal that thermal noise causes

the performance of the device to deteriorate signif-

icantly unless the magnetic energy per flux quantum,

F

2

0

/2L, exceeds about 40k

B

T. At 4.2 K this constraint

places an upper limit on L of about 1 nH. The sim-

ulations yield values of V

F

and the power spectral

density of the voltage noise, S

V

(f). From S

V

(f) one

can obtain the power spectral density of the flux

noise, S

F

(f)S

V

(f)/V

2

F

, and the so-called flux noise

energy, e(f) ¼S

F

(f)/2L. The value of e(f) is minimized

when b

L

2LI

0

/F

0

E1. For optimum b

L

one finds

V

F

ER/L, S

V

(f)E16k

B

TR, and

eðf ÞE16k

B

TðLC=b

c

Þ

1=2

; b

c

t1 ð1Þ

In addition, there is a current noise in the SQUID

loop that often should be taken into account when

the SQUID is coupled to an input circuit.

Equation (1) gives a clear prescription for reducing

e(f): one should reduce T, L, and C. In practice, the

design of SQUIDs is a compromise between these

requirements and other practical considerations. For

example, for photolithographically patterned tunnel

junctions, C will be not less than a few tenths of a

picofarad, and in order to couple flux efficiently to

the SQUID loop, its inductance should be greater

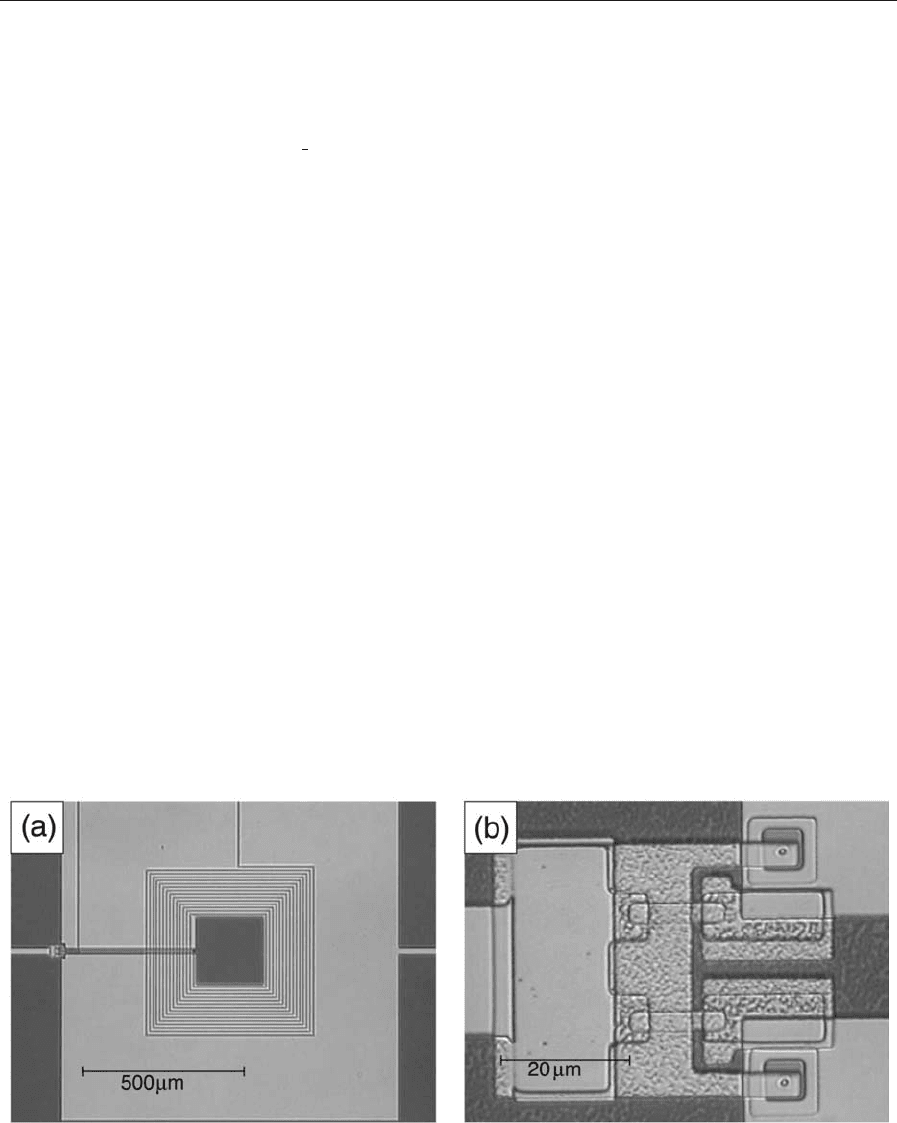

than a few tens of picohenries. The majority of d.c.

SQUIDs in use involve a niobium square washer as

the loop and two resistively shunted Nb–Al

x

O

y

–Nb

tunnel junctions (Fig. 2). The signal to be measured is

coupled in via a niobium spiral coil deposited over

the washer, with an intervening insulating layer; this

arrangement provides efficient magnetic coupling be-

tween the coil and the washer (Ketchen and Jaycox

1982). In typical devices, L is in the range 50–200 pH,

I

0

in the range 5–20 mA, and R in the range 3–10 O.

There are typically n ¼10–50 turns on the coil. The

self-inductance of the coil and its mutual inductance

to the loop are approximately n

2

L and nL, respec-

tively. These devices are fabricated on silicon subst-

rates using standard photolithographic patterning

techniques. The SQUID is often enclosed in a her-

metically sealed assembly, and surrounded by a nio-

bium shield to exclude ambient magnetic field

fluctuations.

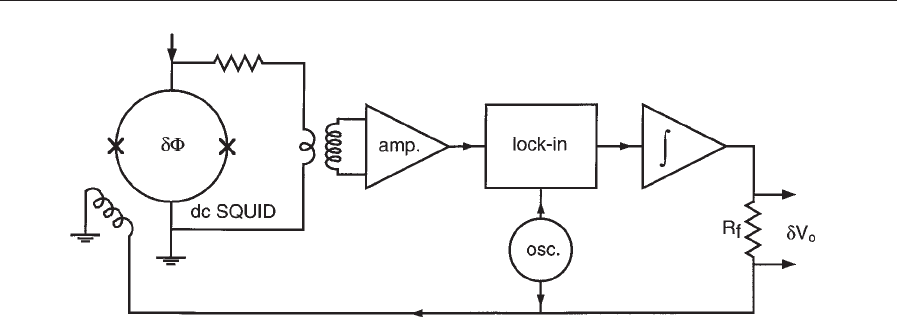

Most SQUIDs are used to measure signals at fre-

quencies up to a few kilohertz, and are invariably

operated in a flux-locked loop (Fig. 3). The output

current of the amplifier chain is fed into a coil cou-

pled to the SQUID so as to maintain the flux thread-

ing it at a constant value. This feedback system

produces a linear response to an input magnetic flux,

Figure 2

(a) d.c. SQUID with 15-turn input coil. (b) Area to left of SQUID washer showing the two junctions and shunt

resistors (courtesy of Xiaofan Meng and Robert McDermott).

1118

SQUIDs: The Instrument

even though it may correspond to many flux quanta,

while enabling one to detect a flux change that is

much less than one flux quantum.

There are a number of different detection and feed-

back systems (Drung 1996). The most widely used

scheme, shown in Fig. 3, involves the application of a

modulating flux, F

m

cos 2pf

m

t, to the SQUID, where

F

m

¼F

0

/4 and f

m

is typically 100 kHz. The resulting

alternating voltage across the SQUID is amplified by

a transformer (often cooled) and a chain of amplifiers,

and is then lock-in detected at frequency f

m

. If the

applied flux in the SQUID is nF

0

, the V–F curve is

symmetric about this local minimum, the voltage

contains components only at 2f

m

, and the output of

the lock-in is zero. When the flux is changed to

nF

0

þdF, there will be a component at f

m

and an

output from the lock-in. After integration, this signal

is fed back to the SQUID via a resistor, R

f

; the volt-

age across this resistor is proportional to dF.

A second popular scheme is ‘‘direct readout,’’ in

which the SQUID is coupled directly to a low-noise

amplifier. The signal from the amplifier is integrated

and fed back to a coil coupled to the SQUID as in the

flux modulation scheme.

Since the amplifier voltage noise is significantly

higher than the intrinsic SQUID noise, the transfer

function of the SQUID is enhanced by ‘‘additional

positive feedback.’’ In this technique, the terminals of

the SQUID are connected across a resistor in series

with a coil that, in turn, is inductively coupled to the

SQUID. When the SQUID is current biased, a

change in the voltage across it due to an applied flux

generates a current in the shunting network and

hence a flux in the SQUID that supports the applied

flux. This scheme has the advantage of relatively

simple electronics, and can operate at frequencies up

to about 10 MHz.

The performance of the d.c. SQUID can be sum-

marized as follows. At 4.2 K the better devices have a

flux noise, S

1/2

F

(f), of 1–2 mF

0

Hz

1/2

, corresponding to

a noise energy of around 100_, at frequencies down to

roughly 1 Hz; at lower frequencies S

1/2

F

(f)scalesap-

proximately as l/f

1/2

. With properly designed electron-

ics, the measured white noise is largely intrinsic to the

SQUID, and its value is in good agreement with com-

puter simulations. Other parameters are determined by

the flux-locked loop. For flux-modulated electronics,

the bandwidth is typically 0–50 kHz, the dynamic

range is 10

7

,andtheslewrateisupto10

7

F

0

s

1

.

2. Flux Transformer

Although the SQUID is very sensitive to magnetic

flux, because of its small area it is not as sensitive to

magnetic fields as one would like for many applica-

tions. For this reason, to make a sensitive magneto-

meter the input coil of the SQUID is connected to an

external superconducting circuit to form a flux trans-

former. Figure 4(a) shows the configuration of a

magnetometer. The inductance of the large area pick-

up loop is approximately matched to the inductance

of the much smaller input coil of the SQUID. Some

flux transformers involve a loop of niobium wire

bonded to the input coil of the SQUID; others consist

of a thin niobium film coupled to the input coil and

fabricated along with the SQUID to make an inte-

grated device. A typical flux transformer enhances

the magnetic field sensitivity by 1–2 orders of mag-

nitude, and the best devices achieve a resolution of

1–2 fT Hz

1/2

at frequencies above a few hertz.

To detect weak signals in a magnetically noisy

environment, most notably in biomagnetic measure-

ments, one generally uses a flux transformer config-

ured as a gradiometer, for example the first-derivative

axial gradiometer shown in Fig. 4(b). The gradio-

meter attenuates magnetic noise from sources at dis-

tances much greater than its baseline—the separation

Figure 3

Flux-locked loop for d.c. SQUID.

1119

SQUIDs: The Instrument