Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Salvaging

What

Was

Left

of

the

American

Wreck

45

ing

the

Americans

to

gather

all

the

benefits.

Therefore

the

article

was

struck

out,

1

but

with

no

intention

of

discarding reciprocity.

The

pur-

pose

was to

guard

it

by

placing

it

upon

a

more

equitable

footing

in

a

supplementary

commercial

treaty.

That

this

would

shortly

follow was

the

understanding

of

both

parties

when

they

signed

the

preliminaries

of

30

November

1782,

the

preamble

of which

retained

a

reference to

the establishment

of

reciprocity;

and when

this draft of the

treaty

was

submitted

to

parliament

in

January

1783,

the

omission of

any

pro-

vision

to

carry

out

the

promise

of the

preamble

at

once roused

great

uneasiness.

The

House of

Commons,

backed

by

the

insistent

demands

of

mer-

cantile

interests

outside,

was

so

impatient

to

get

the freest

possible

trade

with

the

United

States

that

the

government

soon

yielded, prom-

ising

a

bill

to make

provisional

regulations

pending

the

preparation

of

.a

permanent system.

Then

the

government

fell from

power,

for other

reasons;

and

a

few

days

afterward William

Pitt,

who

continued in

office

until a

new

administration

could be

formed,

presented

the bill.

It

offered the

United

States

substantially

all the

advantages,

free

of

any

of

the

disadvantages,

of

being

included

in the

charmed circle of the

British

commercial

system;

therefore

it

was

open

to

all

the

objections

that

had

been

raised

against

the

eliminated

article

of

the

treaty.

Nevertheless

it was

very

much

what

"the whole house" had

wanted,

according

to

the

admission

of

the member

who

opened

the

fight

against

it.

The

shipping

interests

were of

course

stoutly

hostile because the

bill

spelled

the

doom

of their

monopoly,

but the

commercial

and West

Indian interests

fought

hard

for it.

During

the weeks

of warm

debate

that

followed,

various

objections

forced

the

house to

adopt

drastic

amendments.

In the

end,

the

bill,

though

mutilated,

was not

killed;

it was

merely

laid

aside

in

the

hope

that a

better solution was at

hand.

The new

ministry,

of Fox and

North,

reverted

to

the

original plan

and

hoped

a solution

might

be

worked out for

insertion in the

peace

treaty.

Again

the

negotiators

tried

to find

a

satisfactory

formula;

again

the

difficulty

lay

in

Britain,

with

the

navigation

laws;

and

again

London

decided

to

put

off the

question

for settlement in

a

supplementary

treaty,

for Fox was

impatient

to

conclude

peace.

When

he

cut

short

the

discussions and

thrust

forward the

provisional

treaty

of

November

1782,

slightly

reworded

to

make

it

definitive,

the

Americans

were

1

Except

the

provision

for

the

navigation

of the

Mississippi,

which the

Americans

desired in order

to

enlist British

interest

in

preventing Spain

from

closing

the mouth

of

the

river.

46

CHAPTER

FOUR:

reluctant

to

accept

it because their

signatures

would

terminate

their

commission

without their

having

gained

reciprocity.

But

they

too

would rather have an earlier

peace

without

it than

a

later

one

with it.

Thus it

happened

that the mutual

eagerness

of

the

American

commis-

sioners

and

the British

government

to

end

the

war

postponed

the

burial

of the

old

colonial

system.

The

corpse

was

revived

to

vigorous

life before

it could

be laid

away

in the

commercial

treaty

that was to have

supplemented

and com-

pleted

the

peace.

The

revival

was

largely

the work

of

one

man,

who

was no

shipping

magnate

but

a

patriotic

soldier,

accomplished

scholar,

wealthy

landowner,

and

member of

parliament:

Lord

Sheffield.

He

blew a

trumpet

call

that

reverberated

throughout

the

land,

rallying

the

nation behind the

threatened

navigation

laws.

Rarely

has

a

book had

such a

great

and

rapid

influence

upon public

opinion

and

public policy

as his

Observations

on

the

Commerce

of

the

United

States,

which

ran

through

two editions

in 1783 and

reached

a sixth in 1784.

There was

no

need,

Sheffield

asserted,

to

go courting

the

Americans

to

win

back

their

trade.

They

would

still

have to

buy

most

of their

manufactured

goods

from

Britain,

because

they

had

practically

no

industries

whereas she

had the

best in the

world,

and because

only

her

merchants

could

give

the

credit

they

needed.

They

would still have

to

sell

to

her,

since she

offered

the best

market

for their

produce.

By

holding

fast to her

navigation

laws,

under

which

she

had

grown

great,

Britain

could make the

Americans

pay

her

for their own

political

inde-

pendence.

These

laws

would

deprive

them

of their

West

Indian

trade,

the most

valuable

part

of

their

commerce,

and

give

it to

Canada,

Nova

Scotia,

Newfoundland,

and

Ireland.

They

would

also

shift

this

trade

from American

to

British

bottoms,

giving

more

employment

to the

latter than

they

took

away

from

the

former

because

the

voyages

would

be

longer.

Sheffield's

arguments

could

not

be

dismissed as

vain

boast-

ing,

for he

supported

them

with

a

wealth

of

facts

and

figures

gathered

by

painstaking

research

that

made

him

an

outstanding

authority

on

matters

of

trade.

But

the

power

of his

appeal

on

behalf

of

the

navi-

gation

laws was

more

than

logical.

It

was

psychological.

It

did

much

to

revive this

countrymen's

self-confidence,

which

had

been

rudely

shaken

by

the

wreck of

the

empire.

The old

colonial

system,

thus

preserved

for

another

two

generations,

never

completely

enclosed

the

colonial

empire.

The

old

colonies,

which

had burst

through

from the

inside

before

the

Revolution,

burst

through

from

the

outside at

the

close of

the

Revolution.

Britain

was

unable

to

Salvaging

What Was

Left

of

the

American

Wreck

47

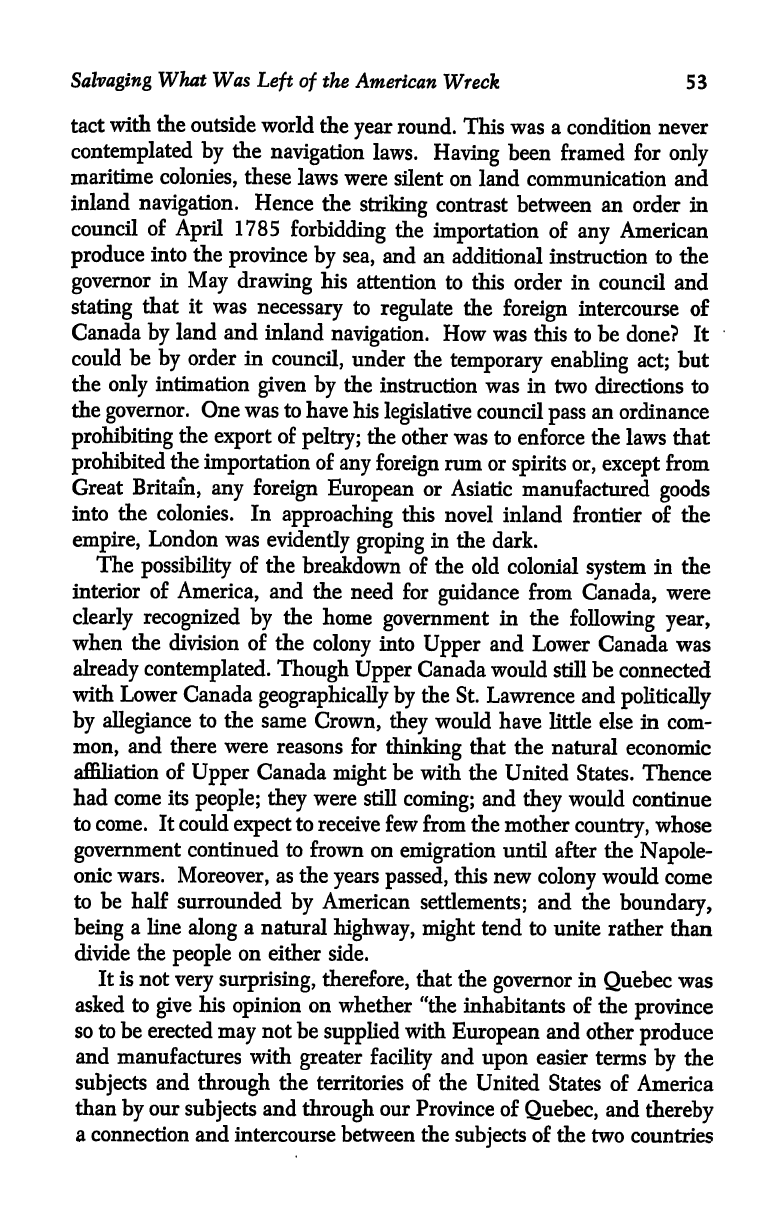

GOLF

OF

The

British

West

Indies

get

peace

without

opening

all

her

North

American

inshore

fisheries-

not

just

those of

Newfoundland

to citizens

of

the United

States

and,

in

addition,

allowing

them to

use

any

unsettled

parts

of

the coasts

of

Nova

Scotia,

Labrador,

and the

Magdalen

Islands

for

purposes

of

drying.

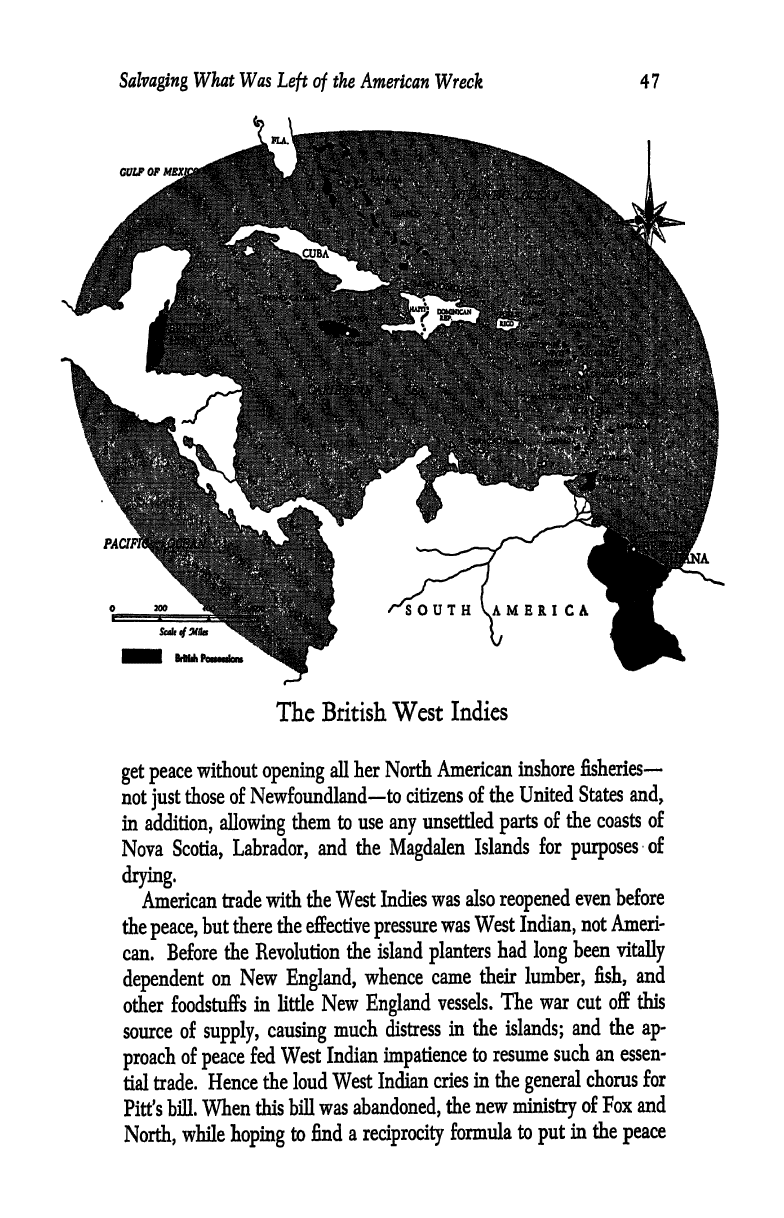

American

trade

with

the

West

Indies

was also

reopened

even

before

the

peace,

but

there

the effective

pressure

was

West

Indian,

not

Ameri-

can.

Before

the Revolution

the island

planters

had

long

been

vitally

dependent

on

New

England,

whence

came

their

lumber,

fish,

and

other

foodstuffs

in

little

New

England

vessels.

The

war

cut

off

this

source

of

supply,

causing

much

distress

in

the

islands;

and

the

ap-

proach

of

peace

fed West

Indian

impatience

to

resume

such an essen-

tial

trade.

Hence

the loud

West

Indian

cries

in the

general

chorus

for

Pitt's

bill. When

this bill

was

abandoned,

the

new

ministry

of

Fox

and

North,

while

hoping

to

find

a

reciprocity

formula

to

put

in

the

peace

48

CHAPTER

FOUR:

treaty,

felt the

necessity

for some more

immediate

action.

Therefore

an act was

passed

to

authorize

temporarily

the

regulation

of

commerce

between

the United States and

the British

Empire by

orders

in council.

The

first

order,

issued

in

May

1783,

modified

a

basic

rule

of

the

old

law

by opening

the

ports

of the

mother

country

to

American

ships

importing

American

unmanufactured

produce.

The

first

order

touch-

ing

the

colonies

followed

in

July

and aimed

at relief

for

the

West

Indies.

It

allowed them

to

import

American

lumber,

flour,

bread,

grain, vegetables,

and

livestock;

and to

export

to

the

United

States

rum,

sugar,

molasses,

coffee,

nuts,

ginger,

and

pimento*

But

it forbade the

importation

of

American

meat,

dairy produce,

and

fish

and

confined

this American

trade to

British

ships.

The

exclusion

of meat

and

dairy

produce

was to

protect

Ireland,

which had

begun

to

supply

the West

Indies with

these

articles

during

the

war;

2

of

fish to

protect

the British

fisheries;

and of

American vessels

to

protect

British

ships,

which

could

not

operate

as

cheaply

as

the

small American craft.

This

exclusion

of

American vessels was

an

unexpected

blow

to

both

the

United States

and

the West

Indies. It

queered

the

pitch

for

the

negotiation

of

reciprocity

then

proceeding

in

Paris,

and

it

shot

prices

up

100

per

cent

in the

islands.

The

planters

were

aghast,

and the

West

India Committee in

England

leaped

into action. The

coalition

govern-

ment

would not

yield;

but

West

Indian

hopes

rose

when

Pitt,

known

as the

friend of free

intercourse,

became

prime

minister in

December

1783.

The

new

administration

intimated

a

willingness

to

compromise

by

admitting

to

West

Indian

ports

American

vessels of

less

than

eighty

tons

in

other

words,

vessels too

small to

engage

in

trade

with

Europe

or to

feed an

American

navy.

The

West

Indians then

overshot

the

mark

by

rejecting

any

limitation of

tonnage,

whereupon

the

govern-

ment

referred

the

whole

question

to

the

new

Committee

of the

Privy

Council for

Trade

and

Plantations

on the

very day

it

was

organized

in

March 1784.

8

For

nearly

three

months

this

privy

council

committee

investigated

the

problem

of West

Indian

trade,

patiently

seeking

and

weighing

all

the available

evidence.

There

were

three

main

considerations.

The

West Indian

merchants

and

planters

did

their

best

to

prove

that

high

costs of

production

would

ruin the

islands

if

they

could

not

get

Ameri-

can

supplies

and

if

their

trade with

the

United

States

was

confined

to

2

In

1778

parliament

opened

colonial trade to

Ireland.

8

For

its

origin

see

infra

p.

56.

Salvaging

What

Was

Left of

the

American

Wreck

49

British

bottoms.

Sir

Guy

Carleton

and all

others

in

England

who

were

best

informed

on

conditions

in

British North

America

testified

that

these

colonies,

if

given

a

proper

advantage

over

the

United

States,

would

soon

be able

to

supply

the

West

Indies

at reasonable

prices

with

all

the

North

American

products

they

needed;

and

that

here

was

a

good

opportunity

to stimulate the

development

of

British

North

Amer-

ica

at the

expense

of the

colonies that

had

revolted

and

to

give

much-

deserved

encouragement

to the

new

Loyalist

settlements.

The

evidence

collected

on

shipping

was

strong:

over

sixty

thousand

seamen

dis-

charged

from

the

navy

on the return

of

peace;

"a

vast

number"

of

merchant

vessels,

with all

their

crews,

released

from

transport

and

other

public

service;

the

fall of transatlantic

freight

rates

to

prewar

levels;

and

the

temptation

of

idle sailors

to

seek

foreign

employment,

thereby

draining

Britain's naval reserve

and

building

up

the maritime

strength

of

her

competitors,

particularly

the

United

States.

Another

consideration

was

the

possibility

of American

retaliation,

but

this

was

lightly

dismissed

for

several

reasons.

The

flourishing

condition of

American

trade

was

deflating

American

indignation

over

the restric-

tion

of

West

Indian

trade

to

British

shipping,

and

neither

the

weak

central

government

nor

the

several

states

were

capable

of

applying

any

effective

pressure.

The

question

was

therefore

decided

on

grounds

that

were

wholly

intraimperial.

The

West

Indians

suspected

that

the

Loyalists

prejudiced

the com-

mittee

in favor

of

British

North

America;

and

there

is

no doubt

that

from

this

time

until

its

fall

two

generations

later,

the old

colonial

system,

on

balance,

worked

for

British

North

America

and

against

the

West

Indies.

But

regard

for

the

Loyalists

was

not

responsible

for

this

preference,

nor

did

it have

any practical

effect

upon

the decision

of

the committee.

Its

conclusion

that

British

North

America could

supply

immediately

a

large

proportion,

and

within

about

three

years

the

whole

of

the

West

Indian

requirements

of

lumber

and

provisions,

though

quite

wrong

on

both

counts,

did

not

visit

any

injury

upon

the

West

Indies.

They

were

already

getting

American

supplies

in British

ships,

which

had

brought

prices

down

from

the

recent

peak;

and

the com-

mittee

would

let

these

supplies

continue

to

flow

as

long

as

necessary,

but

it

would

not

allow

American

vessels,

even

of

small

tonnage,

to

carry

these

supplies.

That

was

the

real

issue,

and

it

was

decided

in

favor

of

British

shipping.

Britain

could

and should

retain

the

monopoly

of

the

carrying

trade

of

her

empire.

The

report

of

the

privy

council

committee

thus

upheld

the

existing

50

CHAPTER

FOUR:

arrangement,

which

had been

made

without

any regard

for

British

North

America;

and these northern

colonies

constituted

only

one

of

several

factors that

might

dictate

a future

change.

Meanwhile

this

compromise

of the old

colonial

system

was continued

on a

year

to

year

basis

until

1788.

By

that

time

it was

fairly

evident

that

the

concession

to

the West

Indies

could not

be

withdrawn

or

curtailed,

and

need

not

be

enlarged.

The islands

were still

dependent

on the

United

States

for

the

great

bulk of

their

supplies.

On

the

other

hand,

the

exclusion

of

American vessels

was not

strangling

them,

for

their

trade

with

the

mother

country,

both

export

and

import,

was

25

per

cent

larger

than

before

the

war,

and some

six hundred

British

ships

were

employed

in

carrying

it.

Therefore Pitt's

government

introduced

a bill

to make

the

existing regulations

permanent,

and

parliament

passed

it with

only

a

flicker

of

opposition.

But the time was

not far off

when

it would

be

impossible

to

keep

American

vessels

out of the

British

West

Indies.

The

adoption

of

the

Constitution

of

the United States

provided

for a

central

government

that

could

retaliate;

and

the

great

war

with

France,

which

began

in

1793,

created new

conditions

that

upset

the act

of

1788.

Meanwhile,

how

did the

closing

in of

the old colonial

system apply

in

British North America?

Newfoundland

had

drawn

so much of its

food from New

England

before the Revolution that

the

return of

peace

brought

pressure

to

reopen

access

to

this source

of

supply.

The

prob-

lem

of the

fishing colony

thus

resembled that

of

the

sugar

islands,

though

it was on

a

much

smaller

scale

and

was

complicated

by

the

necessity

of

sharing

the

"British

shore" with

American

fishermen,

which created

a

greater

possibility

of

smuggling.

Here

too there

was

a vain

hope

that the

Loyalist

settlements

would

obviate the

necessity

of

relying

on the United

States. A

temporary

act

of 1785

permitted

spe-

cially

licensed

British

ships

to

import

American

bread, flour,

and live-

stock into

Newfoundland;

and the

act of

1788,

mentioned

above,

authorized

the

governor

to

continue

this

trade

under

the

same

limita-

tion,

though only

on

a

temporary

basis.

No

vessel

could

get

a

license

more than

seven months

after it

had

cleared

from

a

port

in

the

mother

country.

The Maritime

Provinces,

whose

population

had

been

suddenly

trebled

by

the

influx

of

Loyalists,

were

more

dependent

on

New

Eng-

land.

During

the

first winter

of the

peace,

the

governor

of

Nova

Scotia,

acting

on

no

authority

save

necessity

and

the

advice

of

his

council,

admitted

supplies

from

Boston in

small

American craft.

This

freedom

Salvaging

What Was

Left of

the American

Wreck

51

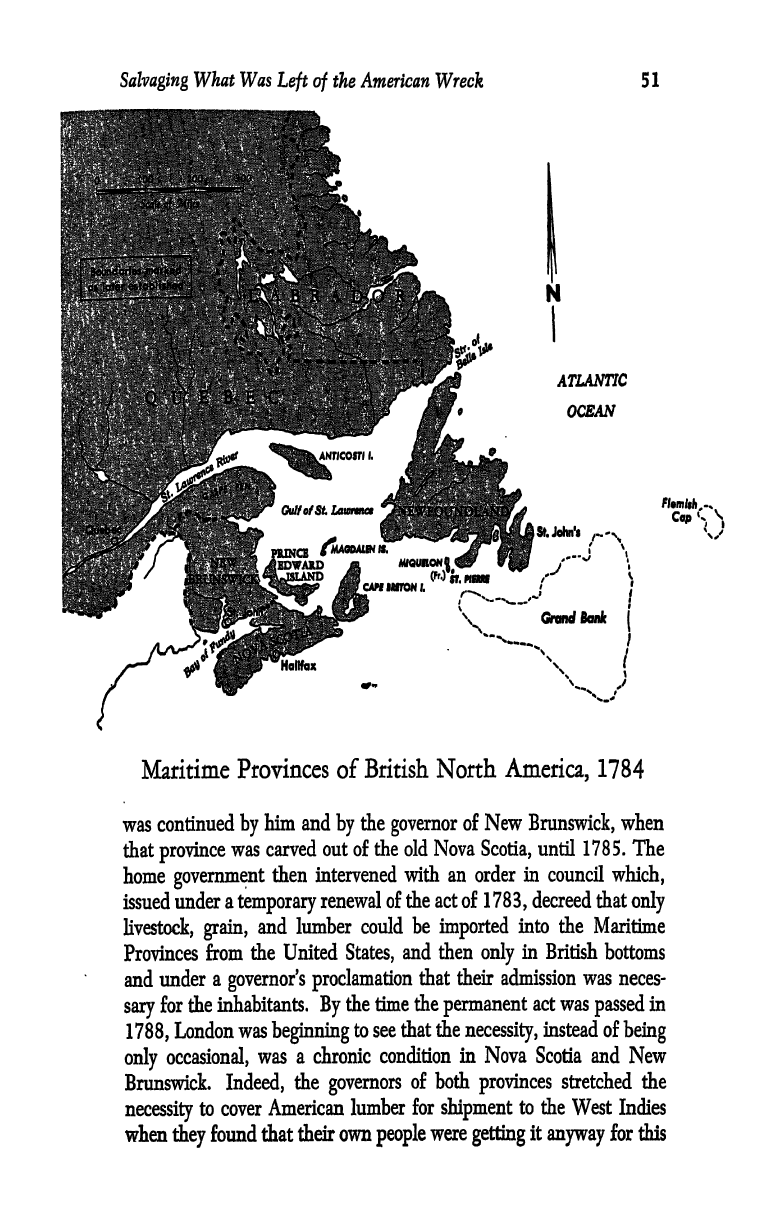

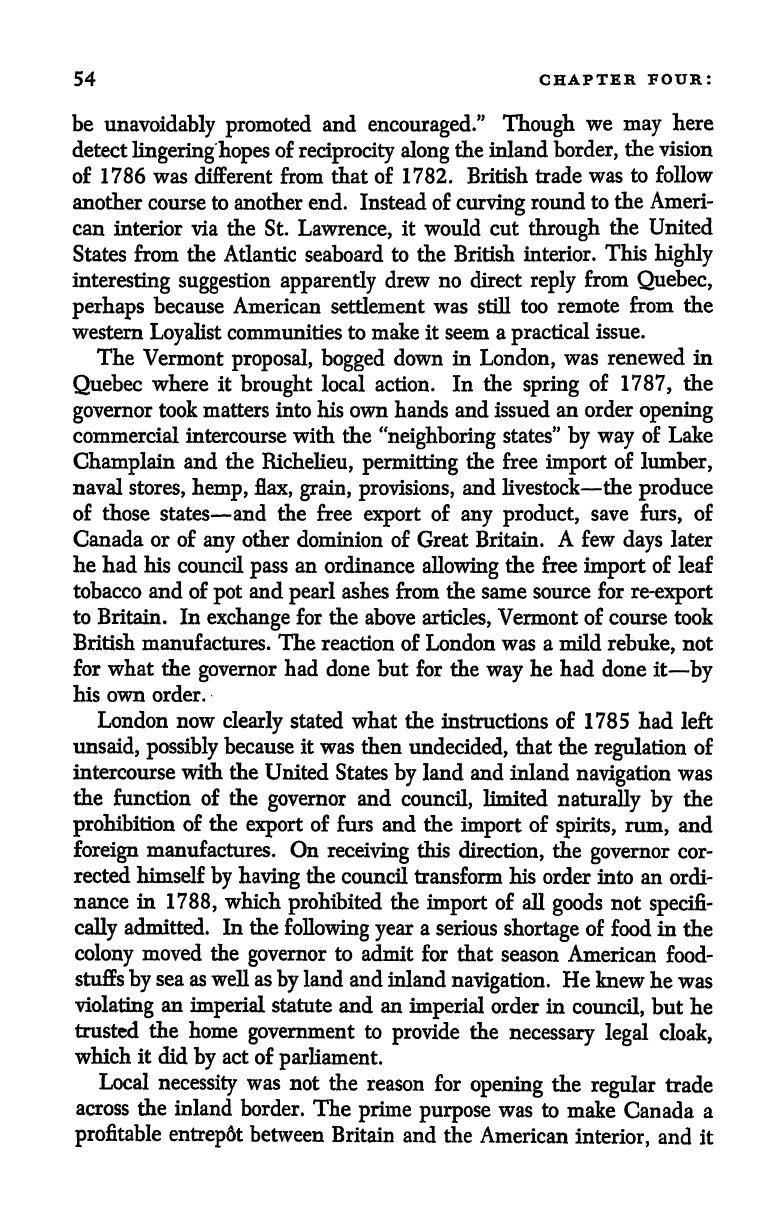

Maritime

Provinces

of

British

North

America,

1784

was

continued

by

him and

by

the

governor

of

New

Brunswick,

when

that

province

was carved

out of

the

old

Nova

Scotia,

until

1785.

The

home

government

then

intervened with an order

in

council

which,

issued

under

a

temporary

renewal of the

act of

1783,

decreed

that

only

livestock,

grain,

and lumber

could be

imported

into the

Maritime

Provinces

from

the

United

States,

and

then

only

in

British

bottoms

and

under

a

governor's

proclamation

that their admission was

neces-

sary

for the

inhabitants.

By

the

time the

permanent

act

was

passed

in

1788,

London

was

beginning

to see

that

the

necessity,

instead

of

being

only

occasional,

was

a chronic

condition

in Nova

Scotia and New

Brunswick.

Indeed,

the

governors

of

both

provinces

stretched the

necessity

to

cover

American lumber

for

shipment

to

the

West

Indies

when

they

found that

their own

people

were

getting

it

anyway

for this

52

CHAPTER

FOUR:

purpose.

Necessity

and

opportunity

also

gave

rise

to an illicit

impor-

tation of American

pitch,

tar,

and

turpentine,

which

the

governors

could not

prevent

and which the home

government

made

licit

by

an

act of

1793.

London,

however,

neither

would

nor

could

do

anything

about the American rum that

poured

into Nova Scotia

and New Bruns-

wick

during

these

years.

It

was

cheaper

than

the domestic

manufac-

ture,

which in turn was

cheaper

than

the

British

West

Indian

product

laid down in

Halifax. There

was no

keeping

it

out

when

American

fishermen were

allowed

by

treaty

to

hover

around these

British

shores

and even

land on

them.

These conditions

suggest

a heaven

for

smug-

glers.

Such was the

intimacy

between the Maritime Provinces

and

New

England

that

the

governor

of Nova

Scotia

asked

permission

to

provide

himself

with an

armed vessel to

keep

this

intimacy

within

legal

bounds.

He

got

the

permission

from

England

and

the

vessel

from

the

United

States.

No such

trade,

legitimate

or

illegitimate,

linked

the

old Province

of

Quebec

with

the

United

States

during

the

first four

years

of

their

peaceful

separation,

because there

was neither

necessity

nor

oppor-

tunity

for

it.

The first

chink in

the

wall was

opened

from the

British

side in

response

to

temptation

from

the

other side

from

Vermont;

and

meanwhile

the

temptation

started

a

highly interesting

investigation

into

the

whole

question

of

economic

relations between

Canada

and the

neighboring Republic.

Vermont was

imprisoned

in

the

interior

and

threatened with

economic

suffocation,

for

the

treaty

of

1783

severed

it

from

the

British

Empire

and the

hostility

of New

York

excluded it

from

the

United

States

until

1791.

During

the

Revolution its

leaders

had

flirted with

the

British

in

Quebec,

discussing

the

possibility

of a

return

to the

old

allegiance.

Both

parties

dropped

this

discussion

when

peace

came,

but

the

Vermonters

could

not

end the

flirtation.

Their

economic

plight

was

too

pressing. They

had

to

get

an

outlet,

and

the

one

provided

by

nature

was

down

Lake

Champlain

and

the

Richelieu

River

to

the

St.

Lawrence.

So

they

knocked at

the

door

of

Quebec

with

proposals

of

commercial reunion

with

the

empire.

Quebec

referred

the

matter

to

London,

and there

the

peculiar

position

of

Vermont

provoked

an

inquiry

early

in

1785

that

revealed

the

peculiar

position

of

Canada.

Here

was

something quite

new

and

very

puzzling

in

the

commercial

system

of

the

British

Empire.

Cut

off

from

the

sea

for

five

months

out

of

every

twelve,

the

old

Province

of

Quebec

was

really

an

inland

colony.

Only

through

a

foreign

country,

the

United

States,

could

it

have

con-

Salvaging

What Was

Left of

the

American

Wreck 53

tact

with the

outside

world

the

year

round. This

was a condition never

contemplated

by

the

navigation

laws.

Having

been

framed for

only

maritime

colonies,

these

laws

were

silent

on land

communication

and

inland

navigation.

Hence

the

striking

contrast between an

order

in

council

of

April

1785

forbidding

the

importation

of

any

American

produce

into the

province

by

sea,

and an

additional instruction to

the

governor

in

May

drawing

his

attention

to this

order

in

council and

stating

that it

was

necessary

to

regulate

the

foreign

intercourse of

Canada

by

land

and

inland

navigation.

How

was

this

to be done? It

could

be

by

order in

council,

under the

temporary

enabling

act;

but

the

only

intimation

given

by

the

instruction was

in

two

directions

to

the

governor.

One was to

have

his

legislative

council

pass

an

ordinance

prohibiting

the

export

of

peltry;

the

other was

to enforce the laws

that

prohibited

the

importation

of

any

foreign

rum or

spirits

or,

except

from

Great

Britain,

any

foreign

European

or

Asiatic

manufactured

goods

into

the

colonies.

In

approaching

this

novel

inland

frontier

of the

empire,

London was

evidently

groping

in the

dark.

The

possibility

of the

breakdown

of

the

old

colonial

system

in the

interior

of

America,

and the

need for

guidance

from

Canada,

were

clearly

recognized

by

the

home

government

in

the

following

year,

when the

division of the

colony

into

Upper

and Lower

Canada was

already

contemplated.

Though Upper

Canada

would still

be

connected

with Lower

Canada

geographically by

the St.

Lawrence and

politically

by allegiance

to the

same

Crown,

they

would

have

little else in com-

mon,

and

there were

reasons for

thinking

that the

natural

economic

affiliation

of

Upper

Canada

might

be with the

United

States.

Thence

had come its

people;

they

were

still

coming;

and

they

would

continue

to come. It

could

expect

to

receive few

from the mother

country,

whose

government

continued

to

frown

on

emigration

until after

the

Napole-

onic wars.

Moreover,

as the

years

passed,

this new

colony

would

come

to be half

surrounded

by

American

settlements;

and die

boundary,

being

a line

along

a

natural

highway, might

tend to unite

rather

than

divide

the

people

on either

side.

It is not

very

surprising,

therefore,

that the

governor

in

Quebec

was

asked to

give

his

opinion

on

whether

"the inhabitants

of

the

province

so to be erected

may

not

be

supplied

with

European

and

other

produce

and

manufactures with

greater facility

and

upon

easier

terms

by

the

subjects

and

through

the territories

of the

United States

of

America

than

by

our

subjects

and

through

our

Province of

Quebec,

and

thereby

a

connection and

intercourse between the

subjects

of the

two

countries

54

CHAPTER

FOUR:

be

unavoidably promoted

and

encouraged."

Though

we

may

here

detect

lingering hopes

of

reciprocity along

the inland

border,

the

vision

of

1786 was

different from

that of 1782. British

trade

was

to

follow

another course

to another

end.

Instead of

curving

round

to

the

Ameri-

can interior via the St.

Lawrence,

it would

cut

through

the

United

States from the Atlantic

seaboard

to the British

interior.

This

highly

interesting suggestion

apparently

drew

no

direct

reply

from

Quebec,

perhaps

because American settlement was still

too

remote

from

the

western

Loyalist

communities

to

make it

seem

a

practical

issue.

The

Vermont

proposal,

bogged

down in

London,

was renewed

in

Quebec

where

it

brought

local action. In

the

spring

of

1787,

the

governor

took

matters

into

his own

hands and

issued

an

order

opening

commercial intercourse with

the

"neighboring

states"

by way

of Lake

Champlain

and the

Richelieu,

permitting

the free

import

of

lumber,

naval

stores,

hemp,

flax,

grain,

provisions,

and livestock

the

produce

of those

states and the free

export

of

any product,

save

furs,

of

Canada

or

of

any

other dominion

of

Great

Britain.

A few

days

later

he

had his

council

pass

an

ordinance

allowing

the free

import

of leaf

tobacco and of

pot

and

pearl

ashes

from the same source

for

re-export

to

Britain. In

exchange

for

the

above

articles,

Vermont of course took

British

manufactures.

The

reaction

of

London

was a

mild

rebuke,

not

for

what

the

governor

had

done but for

the

way

he

had done it

by

his

own order.

London now

clearly

stated what the

instructions of 1785

had left

unsaid,

possibly

because it

was then

undecided,

that

the

regulation

of

intercourse with the

United

States

by

land

and

inland

navigation

was

the

function

of the

governor

and

council,

limited

naturally

by

the

prohibition

of

the

export

of furs

and the

import

of

spirits,

rum,

and

foreign

manufactures. On

receiving

this

direction,

the

governor

cor-

rected

himself

by

having

the

council transform

his

order into

an

ordi-

nance in

1788,

which

prohibited

the

import

of

all

goods

not

specifi-

cally

admitted. In the

following

year

a

serious

shortage

of

food in

the

colony

moved

the

governor

to admit

for

that

season

American

food-

stuffs

by

sea

as well as

by

land and

inland

navigation.

He knew

he was

violating

an

imperial

statute

and an

imperial

order in

council,

but

he

trusted

the home

government

to

provide

the

necessary

legal

cloak,

which

it

did

by

act

of

parliament.

Local

necessity

was

not

the

reason for

opening

the

regular

trade

across

the

inland

border.

The

prime

purpose

was

to

make

Canada

a

profitable

entrep&t

between

Britain

and the

American

interior,

and it