Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

During

the

Long

French

War:

(II)

The Eastern

Hemisphere

165

-~3

X

V

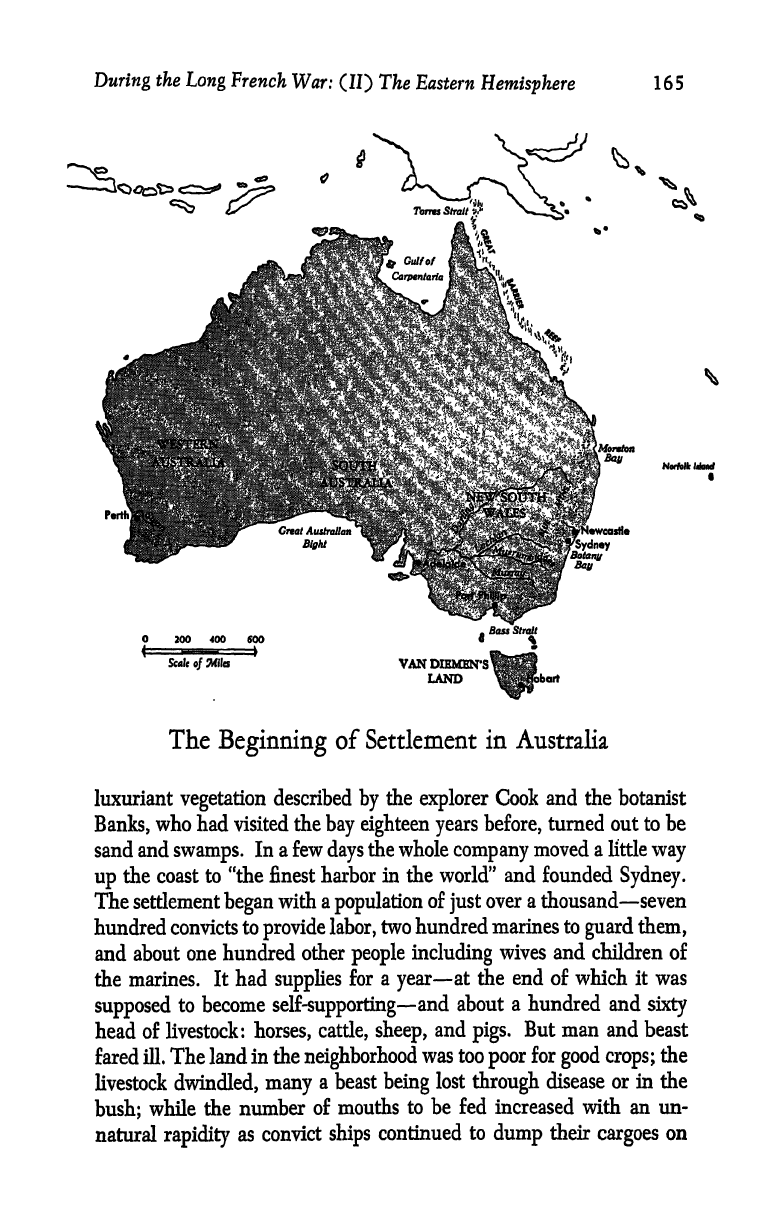

The

Beginning

of

Settlement

in

Australia

luxuriant

vegetation

described

by

the

explorer

Cook

and the

botanist

Banks,

who

had

visited

the

bay

eighteen

years

before,

turned out to be

sand

and

swamps.

In

a few

days

the

whole

company

moved

a little

way

up

the coast

to "the

finest harbor in

the

world"

and founded

Sydney.

The settlement

began

with a

population

of

just

over

a

thousand seven

hundred

convicts

to

provide

labor,

two

hundred marines to

guard

them,

and about

one

hundred

other

people including

wives and children of

the

marines. It had

supplies

for

a

year

at

the

end of which it was

supposed

to become

self-supporting

and

about

a hundred

and

sixty

head

of livestock:

horses,

cattle,

sheep,

and

pigs.

But

man

and

beast

fared

ill

The land

in

the

neighborhood

was too

poor

for

good crops;

the

livestock

dwindled,

many

a

beast

being

lost

through

disease or

in

the

bush;

while

the number

of

mouths

to

be

fed

increased

with an un-

natural

rapidity

as convict

ships

continued

to

dump

their

cargoes

on

166

CHAPTER

TEN:

the

shore.

During

the

early

years

vessels

had

to

be hurried

off to

fetch

food

from

the

Cape,

Batavia,

and China

in

order

to avert

starvation,

and

severe

rationing

was

a

common

experience. Though

better

land

was

shortly

found

and cultivated

at

the

head of the harbor

and

also

further

up

the

coast,

it

was

nearly

twenty years

before the

importation

of

food became

unnecessary.

To

say

that

the

British

government

was

trying

to

build

a

colony

with

the

wrong

kind of

material

is to miss the

whole

point

of this

settlement.

The

raison d'&tre

of New South Wales was

transportation,

not

coloniza-

tion.

The

only

alternative at

that time was more

expensive

and

less

humane.

It was

to

keep

the

convicts in

the

mother

country

where,

since the

American

Revolution

had

stopped

transportation

to

the

old

colonies,

congestion

in

the

jails

and

prison

ships

had

grown

until

they

could hold no more. The

whole

colony

was a

prison

from

which

there

was

practically

no

escape.

The Blue

Mountains,

forty

miles to the

west,

defied

all

efforts

of white

men to

cross

them

until

a

quarter

of

a

century

after the

founding

of

Sydney, by

which

time

the

prison

camp

was

grow-

ing

into a

real

colony;

and

over

the

sea

no other

land was

near

enough

for

fugitives

to

reach in

small

boats.

Of course men

and women

who

were

condemned

to serve

for

seven

years

or

more,

some of

them

for

life,

and

who knew

that

the

government

was

obliged

to

provide

them

with

food, shelter,

and

clothing,

had

little

incentive

to labor.

The

law-

yers

insisted

that

they

were

not

slaves

because

their

persons

were

not

the

property

of the

government,

though

their

services were.

This

was

a

distinction

without a

difference.

Where

they

did differ

from

slaves

was

in

their

being

more

intelligent

and

less

docile.

They

were a

strange

assortment of

people

drawn

from

many

walks

of life

including

the

learned

professions,

and

they

had

little in

common

except

that

all

had

been

caught

in

the

toils

of

the

law.

Most

of

them

were

not

what

we

would

call

jailbirds,

Many

were

victims

of

the

unreformed

criminal

law,

which

prescribed

heavy

penalities

for

what are

now

light

offenses.

A

few

were

radicals

whose

only

crime

was to

be

mistaken

for

revolu-

tionaries.

The

most

troublesome

by

far

were

some

two

thousand

Irish

rebels

who had

been

captured

after

the

rising

of

1798.

More

uncontrollable

than

the

convicts

were

those

who

were

sent

out

to

keep

them

under

control.

The

first

governor

had

some

trouble

with

the

marines,

who

were

as

guardian

angels

compared

with

those

who

soon came

to

replace

them

permanently.

The

New

South

Wales

Corps

was

recruited in

England

for

this

special

purpose

and

therefore

lacked

the

traditional

military appeal

of

glory

and

honor.

Its

officers

and

men

During

the

Long

French

War:

(II)

The Eastern

Hemisphere

167

were

soldiers

in

name

but

not in

character. The rank and

file were

men

whom

no

self-respecting

regiment

would

have;

and

the

officers,

lured

by

promises

of

land,

were

bent on

making

their fortunes

out of

the

colony.

Quite

a

number

of

them

did,

for

they

got

convicts

to work

their

land

and

they

monopolized

the

local

trade,

which was

chiefly

in

spirit-

uous

liquors.

They

debauched the

colony,

and with

their

men behind

them

they

defied

governor

after

governor,

all

naval

officers,

until

at

last

in

1808

they deposed

and

imprisoned Captain

William

Bligh,

of

mutinous

Bounty

fame,

who

had

been

appointed

to bridle

them.

As

the

year

1809

drew to an

end,

the

rule

of

this

unruly corps

came

to

an

end

with the

arrival

of

orders for the

New South

Wales

Corps

to

return

to

England.

A

Highland

regiment

was

sent to

garrison

the

colony,

and

the

commander of

this

regiment

was made the

new

governor.

He was

the

first of

a

line

of

military

governors,

and

his

unit

was

the

first of

a

succession

of

regular

regiments

that

maintained

order

in

this

distant

corner

of

the

empire.

Drink

and the devil did not

have it all

their own

way during

the

days

of naval

governors

and

the

New South Wales

Corps.

These

governors,

being

men of

the

sea,

pushed exploration

around

the coast

of

the con-

tinent;

and the

appearance

of

an

odd

French

vessel,

raising

fears

of

a

French

attempt

at

occupation, inspired

the

planting

of two

subcolonies

in

Tasmania,

then

still known as

Van

Diemen's

Land,

in 1804.

Mean-

while

the

wool

industry

of

Australia

was born.

Its father

was

John

Macarthur,

who

arrived

as

a

lieutenant

of the

corps

in 1790 and

soon

gave

up

his commission

in

order

to take

up

sheep raising.

By

careful

breeding,

particularly

with

some merino

stock

he

procured

from

South

Africa in

1797,

he

proved

that

fortunes

could

be made

in

wool. In 1788

the number

of

sheep

in the

colony

shrank

from

the

original

forty-four

to

twenty-nine;

but

by

1800,

when

Macarthur

sailed

for

England

to learn

more

about

the

business,

the

number

had

grown

to

more than six

thousand.

In

1810

there

were

more

than

twenty-five

thousand,

and

the

following

decade

saw

a tenfold

increase.

Sheep provided

the

pres-

sure that

burst

through

the

forbidding

barrier

on

the west of the

narrow

coastal

region.

All who had

tried to

penetrate

the Blue

Mountains

failed

because

they

followed

the

valleys,

which ended

in blank

walls.

It

was

by following

the

ridges

that

a

party

got

across

in

1813

and

dis-

covered

the

great

grasslands

beyond.

This

was the

beginning

of

inland

exploration

and

expansion,

and

was the

work

not of

government

serv-

ants,

as

the coastal

exploration

had

been,

but of

private

individuals

seeking

room for

sheep,

which

could

now

multiply

indefinitely.

Hence

168 CHAPTER

TEN:

the

tenfold increase

of the second

decade

of

the

century.

The

colony

had

at

last

found its feet.

A

social

emancipation

was

also

proceeding.

Though

free

immigration

was

not

allowed until after the

war and

then took

many

years

to

be-

come

relatively important,

and

though

the

transportation

system

con-

tinued to

augment

the

population

until

well on

in

the

century,

the

colony

contained a

declining

proportion

of

convicts,

and from

being

primarily

a

prison

for their confinement

was

growing

into

a

home

for

their

reformation.

Convicts

were

being

graduated

from

their

hard

school,

some at the

end

of

their

terms and

some

before

it

as

a

reward

for

good

behavior or valuable

service. The former

were

properly

called

"expirees"

and

the

latter

"emancipists,"

but both were often

lumped

together

under

the latter denomination.

As

these

ex-convicts

swelled

in

number,

their

place

in

society presented

a nice

problem;

for

the

free

settlers,

who had

entered the

country

through

the New South

Wales

Corps

or

as civil

servants,

arrogated

unto themselves

the

position

of

a

moral

aristocracy.

The

first

military governor,

Lachlan

Macquarie,

who

restored

discipline

in

the

colony

and ruled until

1821,

tackled

this

problem

boldly,

some

still think

too

boldly.

He

insisted

that

once a

convict became

a

free

man

he was

entitled

to be

treated as such

in

every

respect;

and

being

as much of an autocrat

as his naval

predecessors,

he

did

not hesitate to

appoint qualified

emancipists

to the

magistrates'

bench or other civil office. An

aristocrat

but

no

snob,

this

proud

High-

land

laird also entertained at his own

table

ex-convicts whom

he

found

socially

respectable;

but free

settlers,

whom

he invited at the

same

time,

would not

compromise

themselves

by

sitting

down

to dinner

with

such

companions

even

in

Government House.

London

received

many

bitter

charges against

him

for

favoring emancipists,

and he

may

have

patron-

ized some

who

were

still rascals.

But there was

no

denying

the

fact

that

the best

doctor,

the

only

lawyer,

and some of

the

soundest

business-

men in

Sydney

were

ex-convicts.

Good

was

coming

out

of

evil.

Macquarie

was

the last

of the

"tyrants,"

as all

the first

governors

were

called

because

they

ruled

with

little

check

from

far-off

London

and

with none in

the

colony

except

from

the

lawless

New

South

Wales

Corps.

These

governors

did

not

have

even an

advisory

council.

They

legislated

as

they

saw

fit

and

conducted the

administration

accordingly.

There was

a

criminal

court

designed

by

an

act

of

parliament

in

1787

to

mete

out

justice

in

a

community

of

condemned

criminals

where

trial

by jury

was

simply

out

of the

question.

It was

military

in

composition

and

procedure.

After

the

successful

rising

against

Bligh,

however,

a

During

the

Long

French

War:

(II)

The

Eastern

Hemisphere

169

trained

lawyer

was

sent

from

England

to

preside

over this court.

The

civil

courts,

erected

by

the

governor

on

royal

rather

than

parliamentary

authority,

were

long

manned

by only

amateurs who

should

have fol-

lowed

the laws of the

mother

country

but

knew

little about

them.

Their

decisions

commanded

equally

little

respect,

with the result

that from

the

year

1800

appeals

were

commonly

carried to

England

whenever

the

amount involved

warranted the

expense

until

1812,

when a

local

court

of

appeals

with

an

English

chief

justice

was set

up.

In

parlia-

ment,

which

passed

an

annual

grant

to

cover

the

bills

drawn

by

the

governor

to

pay

the

expenses

of his

government,

there

were

occasional

complaints

of

the

cost,

to

which

the ministers

always

replied

that

no

cheaper

method of

disposing

of

criminals could be

found.

The

amount

for

1815 was

80,000,

when

the

population

was

about

15,000.

The

home

government

seems to

have

thought

it was

getting

its

money's

worth,

and was

pleased

with

the

way

the

Australian

enterprise

was

developing.

This

very

development

was

framing

an awkward

question

for

the

ministers

in

London,

who

did

not

begin

to

see it until

after

the war

was

over.

By

what

right

was the

governor

exercising

such

despotic power

over

free

Britons? This

was no

conquered

colony

where,

by

constitu-

tional

law,

the

authority

of the

Crown

was

supreme

until

it was

re-

nounced

or

parliament

intervened to

regulate

it.

Here the

governor

was

legally

invested

with

power

to

rule

a

society

of

convicts

and their

guardians,

but not of freemen.

Ill

THE

APPROACH

TO

REFORM

Chapters

XL

Overthrow of

the

Landed

Oligarchy

XIL

The

Rise of the Colonial

Office

and

the

Fall

of

Slavery

XIII.

The Growth

of

Anti-Imperialism

CHAPTER

XI

Overthrow

of the

Landed

Oligarchy

WITH

A

REACTIONARY

Tory

party

entrenched

in

power by

the

long

war

which

it had

conducted

to

a

triumphant

conclusion,

Great

Britain

entered

a

period

of

internal

strain and stress. The

foundations

of the

country's

life

had

shifted

from beneath

the old

landed

ruling

class,

which

represented

an

age

that

had

gone

and

yet

clung

tenaciously

to

a

system

of

government

that

excluded other classes

from

power.

Sooner

or later

the

new industrial

society,

which

was

growing

stronger

year

by

year,

would

throw off

the

yoke

of

the

past.

This is

what

happened

in

1832,

after

a

struggle

that shook

the

country

like

an

earthquake.

It

was

a

veritable

revolution,

and

it

brought

in its train

sweeping

measures

of

reconstruction.

The

curse of the French Revolution

was

not banished

with

Napo-

leon. It

still brooded

over the Old

World,

which is

not

surprising

after

the

terrible

experiences

that

Europe

had

suffered

during

the

previous

quarter

of

a

century.

A fierce reaction

ruled

on

the

continent.

Down

in

Rome,

street

lighting

and

vaccination

were

abolished

as revolution-

ary,

having

been

introduced

by

the

French.

Everywhere

the

authorities

were

in

mortal

terror of

revolution

breaking

out

again,

and

they

acted

accordingly,

with

the

result

that

they

only

increased

the

danger

of

explosion.

Revolutions

soon

began

to

pop,

and

they

got

worse

until at

last

in

1848 almost

all

Europe

seemed

to be

blowing

up.

Britain came

through

these

trying

years

without

a

revolution

of

violence,

but

appar-

ently

by

rather

a slim

margin.

The

repressive

policy

of the

government

in

Britain,

though

mild

in

comparison

with

what

was

common

on

the

continent,

was

no

longer

the

persecution

of

an

unpopular

minority.

Now

the

working

class as a

whole

felt

that

it

was directed

against

them,

and this

was

dangerous.

Now

more

than

ever,

the few

throve

on the

misery

of

the

many,

and

the

many

knew

it.

174

CHAPTER

ELEVEN:

British

democracy

was

awakening

slowly

and

painfully.

In

origin

and

character,

it was

the

same

as that which

later

grew

on

the

Euro-

pean

continent,

but

quite

different from American

democracy

of

that

time.

The

North American

environment

emancipated

the

individual.

For little

or

nothing,

the common

man

could

get

good

land

on

which

he

and

his

family

could

lead

an

independent

life. The

cornerstone

of

American

democracy

was the farmer who

worked his

own

farm.

De-

mocracy

in

Britain was the

child of the

industrial

revolution,

which

uprooted

people

from the soil

and

herded

them,

a

great

mass of

prop-

ertyless

wage

earners,

into

crowded urban

centers

where

they

in-

evitably

became

class conscious. There

conditions

kept

the

common

man

down,

and there was no

escape

until,

by

organization

and

struggle,

he

gradually

emancipated

himself.

There

democracy

was a

difficult

achievement of

man,

rather

than a

gift

of

nature;

and

it is

a

nice

ques-

tion whether

democracy

in

America,

where the

condition

that

created

and

sustained

it has

passed

away,

can

survive

unless

it

conforms

to

the

Old World

type,

which

appears

to

be more

permanent.

Though

British

democracy

was

awakening,

it was

not

yet

coherent,

it

did

not

know

how

to

express

itself;

and half a

century

was

to

pass

before the

ordinary

workingman

won the

right

to vote.

For

several

years

after

Waterloo

the

plight

of the

toiling

masses

in

Britain

was

truly

miserable. The

return

of

peace

did

not

bring prosperity.

It

broke

the

war

boom,

throwing many

workingmen

out of

employment,

and at

the

same time it

turned loose

a

flood

of

discharged

soldiers

and

sailors.

The

only

relief it

might

have

brought

cheap

food

was

quickly

denied

by

the

Corn Law

of

18 1 5.

This

prohibited

importation

when

the

domestic

price

was less

than 80

shillings

a

quarter,

which

meant

wheat at

$2.50

a

bushel

nearly

twice

the

daily

wage

of

a

carpenter

and

more

than

twice the

cost

of a

pair

of shoes.

The

law

was

passed

to save

agriculture,

which war

pressure

had

extended to

unprofitable

land,

from

being

ruined

by

the

collapse

of

prices.

It

was

class

legislation

with a

venge-

ance. It

taxed the

multitude

of

consumers

for

the

benefit

of

the few

who

possessed

the

means

of

production,

the

few

being

the

landed

class

who

constituted

parliament.

Another

condition

that

increased the

hardships

of

the

time

was

the

continuance

of

the

industrial

revolution,

now

speeding up,

which

substituted

machines

for

hand labor.

The

misery

of

the

masses

burst

forth

in

riots

all

over

the

country.

The

people

were

desperate

and

they

struck

at

those

whom

they

held

responsible

for their

suffering

at

butchers

and

bakers

whose

shops

they

attacked,

at

landlords

whose

barns

and stacks

they

burned,

and at