Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER

VII

How

Ireland

Nearly

Became

the

First

Dominion

of

the

British

Commonwealth

of

Nations

IRELAND

WAS

England's

oldest

overseas

possession,

the senior

depend-

ent

member of

the

empire;

and

toward

the

close

of the

eighteenth

century

it

gained

such

a

large

measure

of

independence

within

the

empire

that

it

showed distinct

promise

of

becoming

the

first

dominion

of

the British

Commonwealth

of Nations.

Then occurred

one of the

greatest

tragedies

in

the

history

of Ireland

and of

the

empire.

The

curse of

the

French

Revolution descended

upon Anglo-Irish

relations.

The

emergence

of the

modern British Commonwealth was

postponed

for

generations,

until

the

Dominion of

Canada

grew

into the

position

that Ireland

had so

nearly

attained;

and

Ireland

was

thrust back into

subjection,

to become the

festering

sore of British

politics.

To

understand the

Irish

problem,

it

is well to

compare

Ireland with

Wales

and

Scotland

in

their relations

with

England,

which

incorpo-

rated all

three of

them to

form

the

United

Kingdom

under

one

govern-

ment seated in London.

Wales

and Scotland were

no

more

English

than

was Ireland.

Why,

then,

have there not been

corresponding

Welsh

and Scottish

problems?

Obviously

Wales

and

Scotland

were

as

reconciled to

union with

England

as

Ireland

was not.

Why

this

striking

difference?

Much of

the

explanation

lies far in

the

past,

and a

swift

glance

back

at

each of the

three in turn

is

very

enlightening.

Wales,

the

nearest and

weakest,

was

the first to

fall under

English

control,

by

a

piecemeal

conquest

in

the

middle

ages.

But

the

Welsh

were

not

treated

as a

subject

race.

They kept

their

own

language

without

ques-

tionand

they

still do and

only gradually

were

English

laws

and

96

CHAPTER SEVEN:

institutions introduced

among

them.

It

was

characteristic

of the official

English

attitude

that in 1301

the

title

"Prince

of

Wales"

was

conferred

upon

the eldest son

of

the

king.

Wales

turned

Protestant

with

England,

and

at the

same time

it was

formally

merged

with

England,

whose

parliament

was

enlarged

to include

Welsh

members. Welshmen

then

became

the

political

equals

of

Englishmen.

It is

also worth

noting

that the

Tudor

line,

which

ruled

England

at

that

time,

was

Welsh in

origin

and

this was

flattering

to

Welsh

pride.

Scotland

at

that time

was still

an

independent kingdom,

and for

several

hundred

years

had

been

a

nasty

thorn

in the flesh

of

England,

as Ireland

was later

to

become.

Ever

since

the twelfth

century

Scot-

land

had

been

the

ally

of

France,

England's

chronic

foe.

England

had

tried

to

conquer

both

enemies but

had

been

less successful

in Scotland

than

in

France.

It

was

the

triumph

of the

Reformation

in

Scotland

that severed

the

historic Franco-Scottish

alliance

and first drew the

two

kingdoms

of

Great

Britain

together

in defense of

their

common

Protestantism,

which in turn made

it

possible

for

the

king

of Scotland

to

ascend the

throne

of

England

when the Tudor line

died with

Elizabeth

I

in 1603.

This

union

of

the

two

crowns was

acceptable

to

both

kingdoms

because

it

catered to

the

national

pride

of Scotland

without

offending

that

of

England.

The latter

country

was so much

greater

in

wealth,

power,

and

development

that it could have no fear

of

being

annexed

by

Scotland.

Each

country

still

had

its

own inde-

pendent government,

and more than a

century passed

before

they

were

finally

joined

to

form one

realm,

and

then not

by

conquest

but

by negotiated

agreement.

Meanwhile

they

were

associated as consti-

tutional

equals

under the common

Crown,

like the dominions

and

the

mother

country

today.

But

the modern British

Commonwealth could

not

grow

out of this loose

Anglo-Scottish

connection because the two

kingdoms,

sharing

one

little

island,

found that

they

had

to unite

as

one

on

terms

that

were

mutually satisfactory.

Englishmen

were

able to

plant

flourishing

colonies,

to

develop

a

great

shipping

interest,

and to

build

a rich commerce

foreign

as well as

colonial

for

the

benefit

of

England,

while

the

people

of

Scotland could not

do the same

for their

country

because

it

was

relatively poor

and weak.

Scotland,

therefore,

wanted

to share

England's larger

life.

England,

on

the

other

hand,

was alarmed

by

Scottish threats

to choose a

separate

king,

which

would have revived

the

mediaeval

danger

to

England's

rear.

Hence

the

bargain

of

1707,

by

which

the

two countries

were

united

under

a

common

parliament

and

a

common

government

as

well as a

common

How

Ireland

Nearly

Became

the

First

Dominion

97

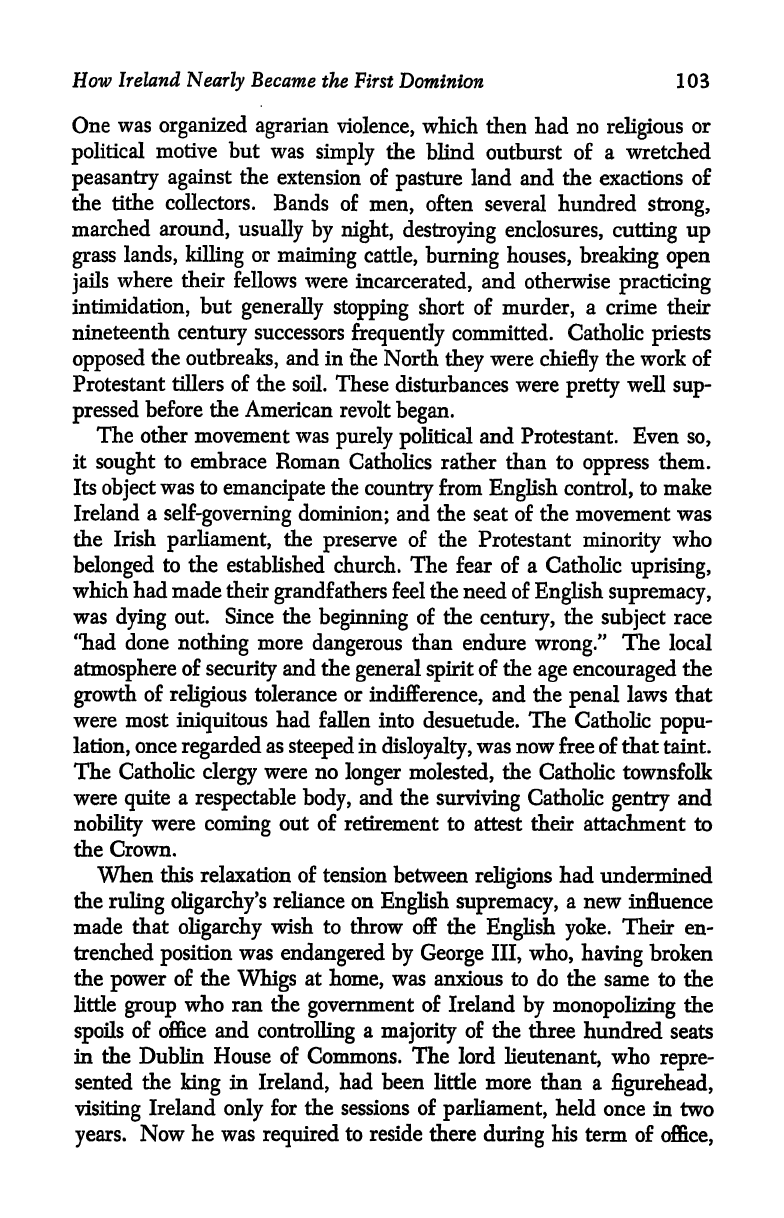

ATLANTIC

OCEAN

IRISH

SEA

Hill

St.

George's

Channel

ip ap

30

.o

50

Stole

of

Miles

BOUNDARY

BETWEEN

NORTHERN

IREUNDj

AND

EIRE

(IRISH

FREE

STATE)

"""

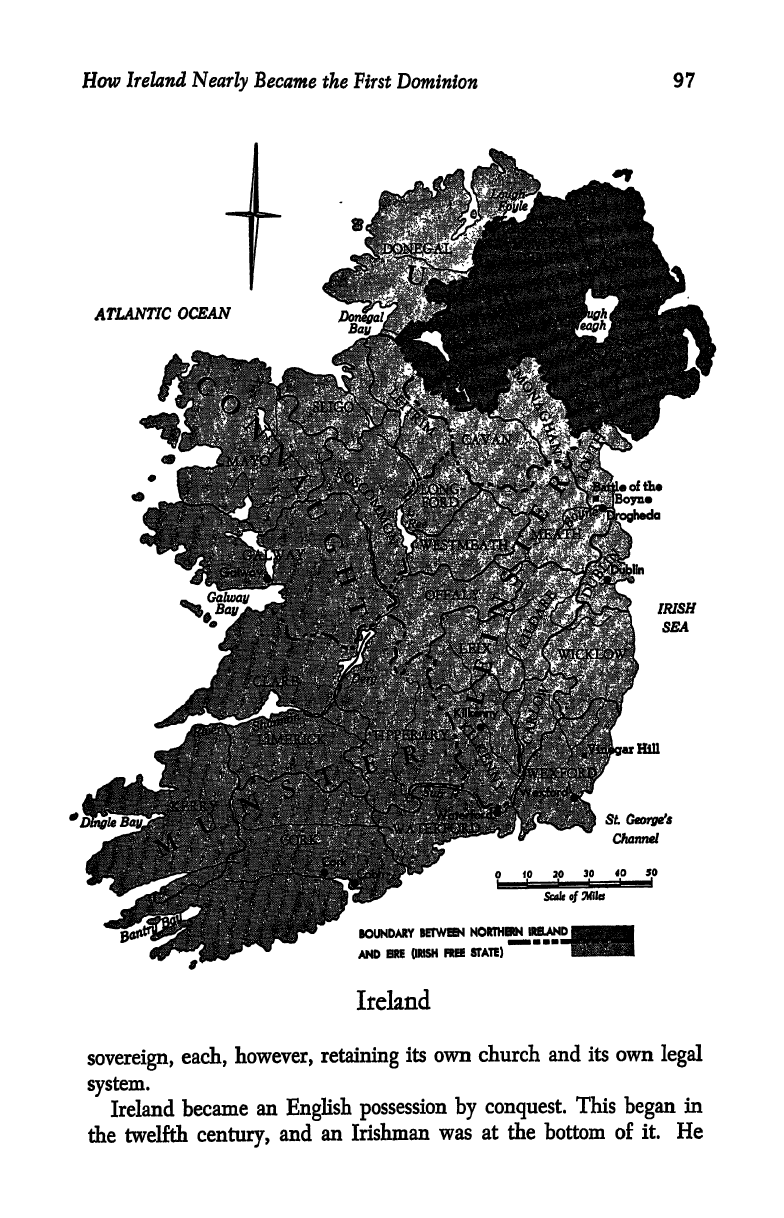

Ireland

sovereign,

each,

however,

retaining

its

own

church

and its

own

legal

system.

Ireland

became

an

English

possession

by

conquest.

This

began

in

the

twelfth

century,

and

an

Irishman

was

at the bottom

of

it. He

98 CHAPTER

SEVEN:

was

Dairmait

MacMurchada

(which

in

plain

English

is

Jeremiah

Murphy),

a

wild tribal chief

who,

by

war and

intrigue,

won

recog-

nition

'as

king

of Leinster. His

many

misdeeds,

which

included

the

abduction

of

die

wife of

a

neighboring

chief

whose

territory

he

coveted,

raised

up

such a

swarm

of

enemies

as

drove

him

from the

island.

Seeking

out

the

king

of

England,

he offered his

allegiance

in

return

for aid in

recovering

his

kingdom.

What he

got

from the

king

of

England

was

merely permission

to

raise

recruits from

among

the

latter's

subjects;

but

he

had little

difficulty

in

enlisting many,

who

were

spoiling

for

such

a

chance to

use

their

swords

in

carving

out

for

them-

selves

broad baronial

estates.

They

had been

doing

this

very

thing

in

Wales,

and

they

found

it easier in

Ireland,

where the terrain

was

less

difficult and the natives

had no

experience

in

meeting

such

well-armed

foes. The

sequel,

however,

was not the

same in the

two

countries.

The

Anglo-Norman

feudal

conquest

of

little

Wales

became

com-

plete,

whereas that

of much

larger

Ireland did

not;

and the

king

of

England

was

able

to

keep

a

tighter

rein

on

his

baronial vassals

in

nearer

Wales

than he could

on their

fellows in distant

Ireland.

Because the

latter

had to live with

hostile native

tribes

as

neighbors,

and

were

freer

to take

the

law into their

own

hands,

their

relations

with

the

Irish

developed

a

bitterness that

was

unknown in

Wales.

Thus in

Ireland

were

"sown

the

seeds of

racial

hatred

which

were

to strike

their

roots

deeper

and

deeper

in

proportion

as

the

differences

of

language,

blood,

and

civilization,

which had

originally

separated

tie

two

populations,

melted into

insignificance."

The

English

colony

in

Ireland

introduced

English

civilization

into

the island.

English

civilization had

also

entered

Scotland,

but much

earlier and

in such a

different

way

that it

greatly helps

to

explain

the

contrast

between Scottish

and

Irish

history.

It

was

by

a

Scottish

conquest

of the northern

part

of

England

in

the

beginning

of

the

tenth

century.

Edinburgh

was

originally

an

English

town,

and

most

of

the

Lowlands

an

English

district.

An

English

block

was

thus

incorporated

into

Scotland,

and

within a

few

generations

the

cruder

and

poorer

Highlands

ceased to be the

predominant

part

of the

northern

kingdom.

Ireland

began

to

be

a

threat

to

England

at

the

close

of

the

middle

ages,

when rival

claimants

to

the

English

throne

got

active

support

from

the

semi-independent

Anglo-Irish

barons.

The

king

then

dis-

patched

Sir

Edward

Poynings

with

an

army

to

establish

the

royal

authority

in

Ireland,

but the

forces

at

the

disposal

of

this

official

were

barely

sufficient

for

the

task

of

confirming

the

English

government's

Haw

Ireland

Nearly

Became

the

First

Dominion

99

control

of the

Pale,

an

English

district

around

Dublin.

Beyond

lay

the

great

estates of

the

Anglo-Irish

magnates

who were

accustomed

to

wage

private

war

among

themselves

and

with their

Irish

neighbors.

All

Poynings

could do

to

check

them

was

to restrict

their

power

over the

Irish

parliament,

which

had

been

set

up

in

the

English colony

after

the

English

pattern,

by

having

it

pass

what

came

to

be

known,

and

in

later

generations

execrated,

as

Poynings'

Laws.

These

subjected

all

Irish

legislation

to the

will

of

the

English

government.

The

Irish

tragedy

deepened

in the

sixteenth

and

seventeenth cen-

turies. The

Tudor

rulers

of

England

forced

the

Reformation

on Ire-

land.

At

first

this

caused

little

trouble,

for

in

Ireland the

old

church

had

fallen

into sad

decay.

But

during

Elizabeth I's

reign

Roman

Catho-

lic

missionaries,

mostly

Jesuits,

poured

into

Ireland,

effecting

a

revival

which

injected

a

religious

fervor

into the

hatred

between the Irish

and

the

English.

Meanwhile

the

English

government

tried

to

assimilate

the

Irish

tribal

system

by

transforming

the

chiefs into

great

landlords,

like

the

descendants of the

Anglo-Norman

conquerors,

with

their clans-

men as

simple

tenants

toiling

for them.

Supported by

grants

of

nobility

and

of

confiscated church

property,

the

attempt

was

more

or less

suc-

cessful,

but

it

produced

some

fierce

uprisings.

Another

novelty

of

the

time

was

the

resumption,

under the

Roman

Catholic

Queen

Mary,

of

English

colonization

in

Ireland.

Lands

swept

clean of Irish

rebels

were settled

with

an

English population

for the

express

purpose

of

strengthening

the

English

interest

in the

island. This

was the

begin-

ning

of

the

plantation policy

which

was to be

carried much

further

in lie

next

century.

As Elizabeth

I's

reign

wore on and

England

drifted into

an

unde-

clared

war

with

Spain,

the

turmoil

in

Ireland

increased

and

disclosed

a

new

menace

to

England.

The

hands of

Spain

and

Rome

became

more

and

more

evident

in

Ireland,

seeking

to

use

it

as a

convenient

base

from

which

to

effect

the overthrow of Protestant

England.

After

the

destruction

of

the

Spanish

Armada,

Philip

of

Spain

relied

chiefly

on

Ireland

to

encompass England's

fall;

and the

old

tribal

Ireland,

for-

getting

the bitter

feuds that had

always

divided

it,

united

in

a

flaming

revolt.

At last

the

English government

did what it

had

never

done

before.

It

sent

to Ireland

sufficient forces

to

complete

the

conquest

of

the

island,

which

was

essential for

England's security.

Though

Spain

backed

the

Irish

with

a

promise

of

aid,

this was

slow

in

coming.

In

1601

a

Spanish

fleet landed

a

Spanish

army

in

Ireland.

It

was

too late.

The back

of

the rebellion

was

already

broken.

The

conquest

of

Ireland

100

CHAPTER

SEVEN:

had

also come too

late,

having

been

postponed

until it

entailed

a

terrific

struggle

in which both

sides

fought

with

savage

ferocity.

Government

troops

even

destroyed crops

with

the

express

purpose

of

reducing

the

peasants by

starvation.

The

present

division

of

Ireland

dates

from

the settlement

that

fol-

lowed

this

subjugation

of

Ireland from

the

great

Ulster

plantation

of 1608 on lands forfeited for treason.

A

company

of

Londoners

got

the town of

Derry,

which

then

became

Londonderry,

and

thousands

of dour

Presbyterians

from

Scotland

were

settled

as tillers of the

soil

in this

part

of Ireland.

These Scots

therefore

took

much firmer

root

than

English

landlords

who lived

on the

rents

paid by

Irish tenants.

It

was then too

that

the

Irish

parliament

received

the

shape

it

preserved

until

it

disappeared

with

the Union

of

1800. It was

enlarged

and

packed

with a

majority

of

Protestants to

bridle

the

political

power

of

the

Catholic

nobility

and

gentry,

Anglo-Irish

as well

as

Irish.

In

1641,

fearing

further confiscations

of land

and

religious perse-

cution,

Catholic

Ireland

rose in arms and fell

upon

the

Protestants,

massacring

many

of them.

England

was horrified but

helpless,

for

she

was

trembling

on the brink

of

her

own civil

war,

which this

Irish

rebellion

precipitated.

Charles I

vainly

tried

to draw

a

Catholic

army

from

Ireland

to

crush the

Puritans

and establish his

despotism

in

England,

but

his

efforts

only

hastened his own

execution

and then

visited an

additional

English

curse

on Ireland. There

Cromwell

and his

fanatical veterans

crushed

the rebels

mercilessly,

killed all

the

priests

they

could

lay

their

hands

on,

and

sought

to

drive the whole

Celtic

population

into

Connaught

so

that the

rest of the

land

might

be

settled

by

English

Protestants.

Though

he

failed to

achieve

this

wholesale

removal,

he

planted

large

numbers of his

own

soldiers

as

yeomen,

and

he

well-nigh completed

the

destruction of the

Irish

gentry,

whose

estates were

turned

over

to

Englishmen.

Outside

Ulster,

which

be-

came

more

intensely

Protestant,

Cromwell's

soldier

settlers

were

geo-

graphically

too

scattered

and

socially

too

cut off from

the

Protestant

gentry

to

preserve

their

English

character

and

their

religion

for

more

than

a

generation,

and the

destruction of

the

native

gentry

delivered

the

Irish

peasants

wholly

into

the

hands

of the

persecuted

priests.

Cromwell's

conquest

of

Ireland

was

more

thorough

than

Elizabeth's,

and

again

was the

price

that

Ireland

had

to

pay

for

England's

secu-

rity,

this

time

against

the

danger

of

a

royalist

reconquest

of

England

from

Ireland,

which

would

have

destroyed

liberty

in

England.

Scot-

land

likewise

threatened

England

at

this

time,

and,

as a

consequence,

How

Ireland

Nearly

Became the First

Dominion

101

experienced

its

only

real

conquest

by

England.

But

the

English

army

was

soon

withdrawn,

when

the

Stuarts were

peacefully

restored

in

1660,

and

Scotland

recovered

its

independence

under the

same

crown.

Ireland,

on

the other

hand,

suffered new disabilities.

It was

regarded

as

a

colony,

whose

economic interests should be sacrificed

for

those

of

England.

This,

of

course,

was a

basic

principle

of

the

old

colonial

system,

which was then

being developed;

but Ireland

was

singled

out

for

special

treatment because it

was

the

only

colony

that

offered

serious

economic

competition

with

England.

Selfish

interests

in the

English

parliament

insisted on

excluding

Ireland

from

the

benefits

of the

navi-

gation

laws,

thereby

ruining

a

promising

Irish

shipping,

and

on

pro-

hibiting

the

importation

of

livestock,

meat,

butter,

and cheese

from

Ireland,

to

the

infinite

damage

of

producers

in

that

unhappy

island.

Much

worse

was the fate that befell

Ireland on

the morrow

of

the

English

Revolution

of

1688,

because

England's

security

was

again

at

stake

in

Ireland.

King

James

II,

driven

from

his throne

because

he

tried

to

force

Roman Catholicism

and

despotism

upon

England,

fled

to

France

for

aid,

and with French

troops

turned

up

in Ireland

to

rally

that

country

for the

reconquest

of his

throne.

He

called

a

Roman

Catholic

Irish

parliament

that

enacted

a

wholesale attainder

of Protes-

tants

and the

confiscation

of

their

property;

and he

made

war

upon

them

to

extirpate

them,

as

a

preliminary

step

to his

invasion

of

England

with

a Roman

Catholic

army

at

his back.

The

Protestants

were cor-

nered

in

a

little

bit

of

Ulster

and

were

nearly

exhausted

before

they

were

saved

by

relief from

England.

William

of

Orange,

the

new

king

of

England,

followed

with a

strong

army

to

reconquer

Ireland before

he

could

turn

on

his

principal

foe,

which

was

France.

For

a while

the

issue

was

in doubt

because

the

French

defeated

the

English

fleet

and

were,

therefore,

free

to

land

a

French

army.

It

came

in 1691

but,

like the

Spanish

army

of

ninety years

before,

it was

too

late,

for William

had

already

won

a decisive

victory

over

the Irish.

Before the

year

was

out

the

Irish

war

was

over,

and

for

a third

time,

out

of

self-defense,

England

had

completely

conquered

Ireland.

The

fright

that

Ireland

had

again

given

England,

and

the

nightmare

of

terror

from

which

Irish

Protestants

had

just

recovered,

inspired

a

grim

determination

to

crush

Catholic

Ireland

forever;

to this

end,

law

was

piled

upon

law

during

the

next

half

generation.

The Roman

Catholics,

who

formed

at least

three

quarters

of

the

population,

were

deprived

of

all

civil

rights,

their

property

was

confiscated,

their

educa-

tion

was

proscribed,

and

their

clergy

were

outlawed.

These

penal

laws

102

CHAPTER SEVEN:

were

almost as monstrous

as the

measures

that had

recently

harried

the

Huguenots

out

of

France. Catholic

Ireland

was

so

prostrate

that

it

did not stir

during

the

rest

of

England's

long

struggle

against

Louis

XIV or her wars with France

in

the middle

of

the

eighteenth century.

Even

Irish

Protestants

suffered,

though

much less

severely,

from

legislation passed by

the

newly

sovereign

parliament

in

London,

under

the influence

of

Anglican

religious

intolerance

and

English

commer-

cial

jealousy.

It

excluded from

every public

office

the

loyal

Presby-

terians

of

Ulster,

who

were

reinforced

by immigration

from

Scotland

until

they

perhaps

equalled

in

number the

Episcopalian

Protestants in

Ireland;

and

it

forbade

the

export

of Irish

woolen

goods

to

any

country

except England,

which had

earlier

imposed prohibitive

duties

upon

them. Irish

landowners,

mostly

members of

the established

church,

when

hit

by

the

closing

of

the

English

market to

their

livestock

and

meat,

had

turned

to

the

production

and manufacture of wool on

a

large

scale,

which

profitable

business was

now

strangled.

The

only prosperous

part

of

Ireland

was Protestant

Ulster,

the

home

of

the linen

industry,

which

England

encouraged, having practically

none

of

her

own. The rest of the

country

was

in

a

deplorable

state,

and

the

economic

plight

of the Irish

peasants

was

the worst

of

all.

Crowded

on diminutive

holdings

and without

any security

of

tenure,

they

had to

pay

rackrents forced

up

by

their own

competition

for

land,

the

only

thing

that

stood between

them

and

certain

starvation.

They

also had

to

support

two

churches,

their own and a

hated

one,

hated

all

the more because

the

tithe-jobbers,

who

bought

the

rights

of the

clergy,

were a race of

harpies.

Already

"Raleigh's

fatal

gift"

was the

staple

food,

which

meant

three

"meal

months" or

"hungry

months"

before

there were new

potatoes

to

dig.

The

blight

of absentee

proprietorship

rested

heavily upon

the

country.

Jonathan

Swift

declared that at

least

one third

of all

the

Irish

rent was

spent

in

England.

Rarely

was

any

revenue from an estate

put

back

into it. The

land was

usually

leased

and

subleased

by

Protestant

middlemen who

battened on

the half-

starved,

half-naked

peasants

living

in mud

hovels of their

own

con-

struction.

English

colonization

exhibited no

more

concern for the

Irish

natives

than it did for the red

men it

encountered in

North

America

or

the

black men it

imported

into

the

Caribbean

colonies.

By

the time of

the

American

Revolution new life

was

stirring

in

Ireland.

The

previous

decade

had

seen

the

beginning

of

two

move-

ments

that were

to

color

Irish

history

down to our

own

day.

Though

later

they

ran

together,

there

was

yet

no

connection

between

them.

How

Ireland

Nearly

Became

the First

Dominion 103

One

was

organized

agrarian

violence,

which

then had

no

religious

or

political

motive but

was

simply

the

blind outburst of

a

wretched

peasantry

against

the

extension of

pasture

land and

the exactions

of

the

tithe

collectors.

Bands

of

men,

often

several hundred

strong,

marched

around,

usually

by

night,

destroying

enclosures,

cutting

up

grass

lands,

killing

or

maiming

cattle,

burning

houses,

breaking

open

jails

where their

fellows

were

incarcerated,

and

otherwise

practicing

intimidation,

but

generally

stopping

short of

murder,

a

crime

their

nineteenth

century

successors

frequently

committed. Catholic

priests

opposed

the

outbreaks,

and

in

the

North

they

were

chiefly

the

work

of

Protestant

tillers

of the

soil. These

disturbances were

pretty

well

sup-

pressed

before the

American

revolt

began.

The other

movement

was

purely political

and Protestant. Even

so,

it

sought

to embrace

Roman

Catholics rather than to

oppress

them.

Its

object

was

to

emancipate

the

country

from

English

control,

to make

Ireland

a

self-governing

dominion;

and the seat of the movement was

the

Irish

parliament,

the

preserve

of the Protestant

minority

who

belonged

to the

established church. The fear of a Catholic

uprising,

which

had made

their

grandfathers

feel the need of

English

supremacy,

was

dying

out. Since

the

beginning

of the

century,

the

subject

race

"had

done

nothing

more

dangerous

than endure

wrong."

The

local

atmosphere

of

security

and the

general

spirit

of

the

age encouraged

the

growth

of

religious

tolerance or

indifference,

and the

penal

laws that

were most

iniquitous

had fallen

into desuetude. The Catholic

popu-

lation,

once

regarded

as

steeped

in

disloyalty,

was now free

of that

taint.

The Catholic

clergy

were

no

longer

molested,

the

Catholic townsfolk

were

quite

a

respectable

body,

and the

surviving

Catholic

gentry

and

nobility

were

coming

out

of retirement

to attest their attachment

to

the Crown,

When

this relaxation of tension

between

religions

had undermined

the

ruling oligarchy's

reliance on

English supremacy,

a

new influence

made

that

oligarchy

wish

to throw

off the

English yoke.

Their

en-

trenched

position

was

endangered

by

George

III,

who,

having

broken

the

power

of

the

Whigs

at

home,

was anxious

to do the

same

to the

little

group

who

ran the

government

of Ireland

by

monopolizing

the

spoils

of

office and

controlling

a

majority

of the

three

hundred seats

in

the

Dublin

House of Commons. The

lord

lieutenant,

who

repre-

sented

the

king

in

Ireland,

had been little

more

than

a

figurehead,

visiting

Ireland

only

for

the

sessions

of

parliament,

held once

in two

years.

Now

he was

required

to reside there

during

his term

of

office,

104

CHAPTER

SEVEN:

to take

the

business

of

patronage

out

of

the hands

of the

Undertakers,

as

they

were

called

because

they

had

"undertaken"

to

manage

parlia-

ment,

and

to

manage

the

government

himself

under

direction from

London.

Thus

the

problem

of

imperial

control

was

coming

to

a

head

in

Ireland

at

the

same

time

as in

the

American

colonies.

The

American

Revolution

had

a

profound

effect

upon

Ireland. Yet

there

it

produced

no

sign

of a

revolutionary uprising,

even

among

the

Presbyterians

in

Ulster,

who were

"fiercely

American."

The

Catholics

were

never

quieter;

their

principal

noblemen

responded eagerly

to a

government

request

for

aid in

raising troops,

the old

ban on

Catholic

enlistments

having

been

ignored

for

many years;

and

their

gentry

seized

the

occasion

to

present

addresses

of

loyalty

condemning

the

violence

of the

Americans.

The

Anglican

minority,

however,

were

far

from

unanimous in

backing

British

authority

in

America,

for

many

of

them

realized

that

the

American

cause was

theirs

too.

Still

they

would

use

only

constitutional

means to

get

rid

of

British

authority

in

Ireland.

The

strength

of the

Irish

parliamentary

opposition

grew,

reinforced

by

the

election of

Henry

Grattan,

under

whose

eloquent

leadership

it

concentrated

upon

the

removal

of

trade

restrictions

and

the

establish-

ment

of Irish

legislative

independence;

and the

Irish

political

struggle

led

both

sides to

cultivate

the

favor

of the

Catholics.

Grattan

would

grant

them

the

same

legal

and

political

rights

as

Protestants,

and

the

government

of

Lord

North

was not

unfriendly

to

Catholic

claims,

with

the

result that an

Irish

act of

1778

repealed

invidious

limitations

upon

Catholic

purchase

and

inheritance

of

land,

and

the

preamble

of

the

new law

enunciated

the

general

principle

"that

all

denominations

should

enjoy

the

blessings

of

our

free

constitution."

It

was a

good

augury

that

real

reform

began

in

Ireland with

a

concession to

Catholics

and

a

promise

of

more

to

come.

In

the

same

year

a

British

act

admitted

Irish

vessels

to

the

privileges

of

British

vessels

under

the

navigation

laws.

Ireland

was

drawing

together

and

becoming

a

nation.

When

the

American

war

widened

into

a

European

one

with

the

entry

of

France and

Spain,

and

their

navies

qualified

the

British

com-

mand

of

the

sea,

a

hostile

invasion

of

Ireland

seemed

imminent.

Neither the

British

nor

the Irish

government

could

provide

the

forces

to meet

it,

while

the

French

government

hoped

for

an

Irish

rebellion

to aid the

invasion;

but

the

nascent

Irish

nation

rallied

to the

defense

of

the

country.

Under

the

direction

of

the

leading

gentry,

the

people

flew

to

arms,

elected their

own

officers,

met

regularly

for

military

drill,