Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Managers’ compensation wouldn’t depend on divisions’ market values because no

shares in the divisions would be traded and plans for sale or spin-off would not be

part of the conglomerate’s financial architecture.

The advantages of LBO partnerships are obvious: strong incentives to man-

agers, concentrated ownership (no separation of ownership and control), and lim-

ited life, which reassures limited partners that cash flow will not be reinvested

wastefully.

These advantages carry over to other types of private equity partnerships, in-

cluding venture capital funds. We do not say that this financial structure is appro-

priate for most businesses. It is designed for change, not for the long run. But tra-

ditional conglomerates don’t seem to work well for the long run, either.

Conglomerates around the World

Nevertheless, conglomerates are common outside the United States. In some

emerging economies, they are the dominant financial structure. In Korea, for ex-

ample, the 10 largest conglomerates control roughly two-thirds of the corporate

economy. These chaebols are also strong exporters so that names like Samsung and

Hyundai are recognized worldwide.

Conglomerates are common in Latin America. One of the more successful, the

holding company

36

Quinenco, is in a dizzying variety of businesses, including ho-

tels and brewing in Chile, pasta making in Peru, and the manufacture of copper

and fiber optic cable in Brazil.

Why are conglomerates so common in such countries? There are several possi-

ble reasons.

Size You can’t be big and focused in a small, closed economy: The scale of one-

industry companies is limited by the local market. Scale may require diversifica-

tion. There are various reasons why size can be an advantage. For example, larger

companies have easier access to international financial markets. This is important

if local financial markets are inefficient.

Size means political power; this is especially important in managed economies

or in countries where the government economic policy is unpredictable. In Korea,

for example, the government has controlled access to bank loans. Bank lending has

been directed to government-approved uses. The Korean conglomerate chaebols

have usually been first in line.

Undeveloped Financial Markets If a country’s financial markets are substandard,

an internal capital market may not be so bad after all.

“Substandard” does not just mean lack of scale or trading activity. It may mean

government regulations limiting access to bank financing or requiring govern-

ment approval before bonds or shares are issued.

37

It may mean information in-

efficiency: If accounting standards are loose and companies are secretive, moni-

toring by outside investors becomes especially costly and difficult, and agency

costs proliferate.

980 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

36

A holding company owns controlling blocks of shares in two or more subsidiary companies. The hold-

ing company and its subsidiaries operate as a group under common top management.

37

In the United States, the SEC does not have the power to deny share issues. Its mandate is only to as-

sure that investors are given adequate information.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

In many countries, including some advanced economies, minority investors are

not well protected by law and securities regulation. Sometimes there are blatant

transfers of wealth from outside shareholders to insiders’ pockets. It’s no surprise

that financial markets in such countries are relatively small.

Recent research by Rafael LaPorta and his colleagues finds a strong associa-

tion between legal systems and the development of financial markets and the

volume of external finance.

38

Minority shareholders seem to be best protected in

common-law systems such as those in the United States, Great Britain, and other

English-speaking countries. Civil-law systems, such as those in France and

Spanish-speaking countries, offer less effective protection; consequently, finan-

cial markets are less important in such countries. The volume of external fi-

nancing is low. Financing tends to flow instead through banks, within large, di-

versified companies, or among members of groups of associated companies.

Many of these companies or groups are controlled by families.

The Bottom Line on Conglomerates

Are conglomerates good or bad? Does corporate diversification make sense? It de-

pends on the task at hand and on the business, financial, and legal environments.

If the task is fundamental change, then the required management skills and

knowledge may not be industry-specific. For example, the general partners in LBO

funds are not industry experts. They specialize in identifying potential diet deals,

negotiating financing, buying and selling assets, setting incentives, and choosing

and monitoring management. It’s no surprise that LBO funds end up with diver-

sified portfolios; they invest wherever opportunities crop up. But these same skills

are not best for long-run operation and growth. Thus LBO funds and other private

equity partnerships are designed to force the managers of change to hand over the

reins once change is accomplished.

If the task is managing for the long run, and the company has access to well-

functioning financial markets, then focus usually beats diversification. Conglom-

erates have a hard time setting the right incentives for divisional managers and

avoiding cross-subsidies and overinvestment in the internal capital market.

In less developed countries, conglomerates can be effective. Local history and

practice have led to diversified companies or groups of companies. Also, diversifi-

cation means scale, and size counts when local financial markets are small or un-

developed, when the company needs to attract the best professional managers, and

when assistance or protection from the government is required.

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 981

38

R. LaPorta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny, “Law and Finance,” Journal of Political Econ-

omy 106 (December 1998), pp. 1113–1155 and “Legal Determinants of External Finance,” Journal of Fi-

nance 52 (July 1997), pp. 1131–1150.

34.4 GOVERNANCE AND CONTROL IN THE UNITED

STATES, GERMANY, AND JAPAN

For public corporations in the United States, the agency problems created by the

separation of ownership and control are offset by

• Incentives for management, particularly compensation tied to changes in

earnings and stock price.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

• The legal duty of managers and directors to act in shareholders’ interest,

backed up by monitoring by auditors, lenders, security analysts, and large

institutional investors.

• The threat of a takeover, either by another public company or a private

investment partnership.

But don’t assume that ownership and control are always separated. A large

block of shares may give effective control even when there is no majority owner.

39

For example, Bill Gates owns over 20 percent of Microsoft. Barring some extreme

catastrophe, that block means that he can run the company as he wants to and as

long as he wants to. Henry Ford’s descendants still hold a class of Ford Motor

Company shares with extra voting rights and thereby retain great power should

they decide to exercise it.

40

Nevertheless, the concentration of ownership of public U.S. corporations is much

less than in some other industrialized countries. The differences are not so apparent

in Canada, Britain, Australia, and other English-speaking countries, but there are

dramatic differences in Japan and continental Europe. We start with Germany.

Ownership and Control in Germany

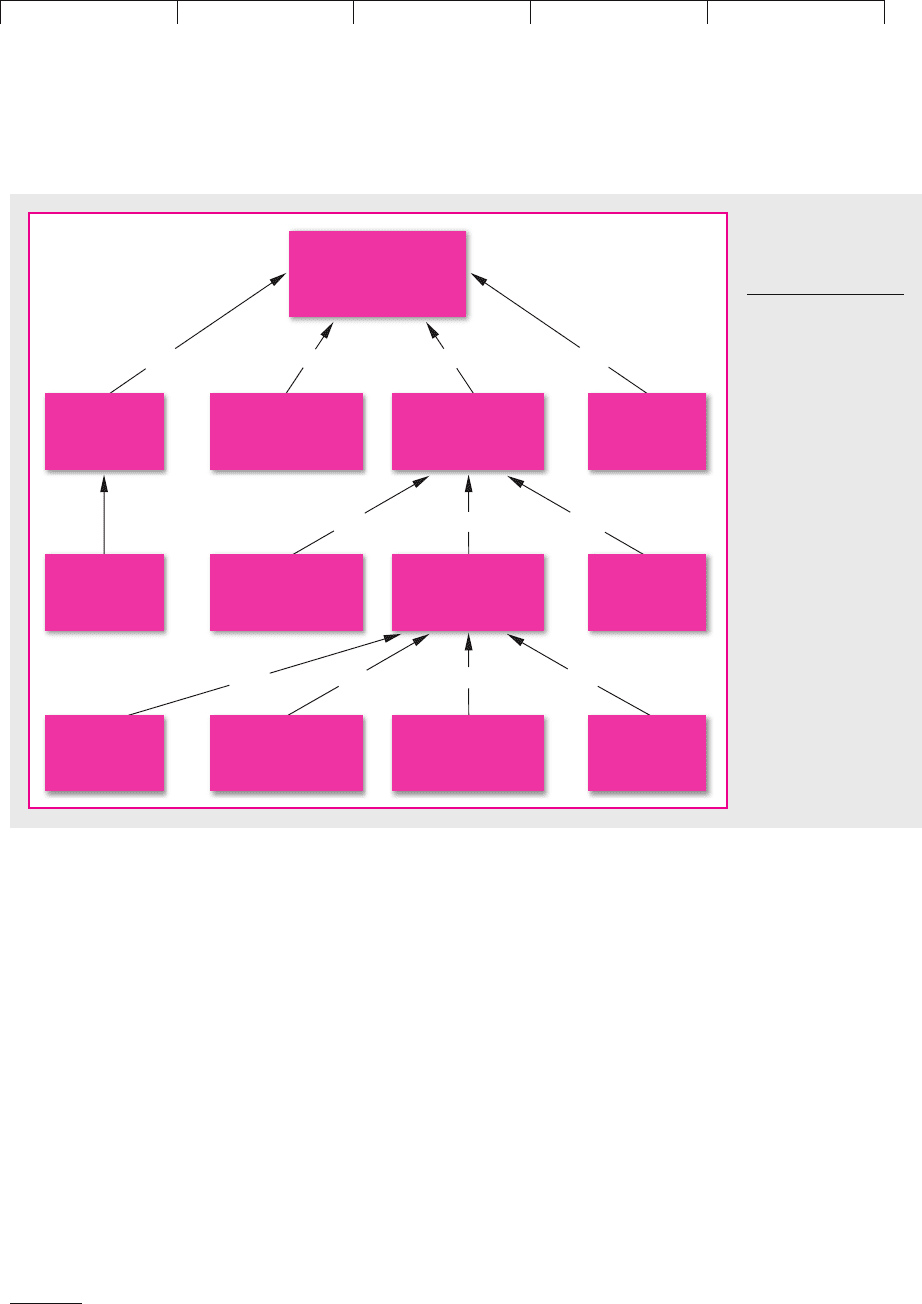

Figure 34.3 summarizes the ownership in 1990 of Daimler-Benz, one of the largest

German companies. The immediate owners were Deutsche Bank, the largest Ger-

man bank, with 28 percent; Mercedes Automobil Holding, with 25 percent; and the

Kuwait government, with 14 percent. The remaining 32 percent of the shares were

widely held by about 300,000 individual and institutional investors.

But this was only the top layer. Mercedes Automobil Holding was half owned

by two holding companies, “Stella” and “Stern” for short. The rest of its shares

were widely held. Stella’s shares were in turn split four ways: between two banks;

Robert Bosch, an industrial company; and another holding company, “Komet.”

Stern’s ownership was split four ways too, but we ran out of space.

41

The differences between German and U.S. ownership patterns leap out from

Figure 34.3. Note the concentration of ownership of Daimler-Benz shares in large

blocks and the several layers of owners. A similar figure for General Motors would

just say, “General Motors, 100 percent widely held.”

In Germany these blocks are often held by other companies—a cross-holding of

shares—or by holding companies for families. Franks and Mayer, who examined

the ownership of 171 large German companies in 1990, found 47 with blocks of

982 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

39

A surprising number of public U.S. corporations do have majority owners. A study by Clifford Hold-

erness and Dennis Sheehan identified over 650. See “The Role of Majority Shareholders in Publicly Held

Corporations: An Exploratory Analysis,” Journal of Financial Economics 20 (January/March 1988),

pp. 317–346.

40

You would predict that companies with concentrated ownership would show better financial per-

formance simply because the blockholders face less of a free-rider problem when they represent share-

holders’ interests. This prediction appears to be true. However, investors who accumulate very large

stakes and gain effective control of the firm may act in their own interests and against the interests of

the remaining minority shareholders. See R. Morck, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny, “Management Owner-

ship and Market Valuation: An Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Financial Economics 20 (January/March

1988), pp. 293–315.

41

A five-layer ownership tree for Daimler-Benz is given in S. Prowse, “Corporate Governance in an In-

ternational Perspective: A Survey of Corporate Control Mechanisms among Large Firms in the U.S.,

U.K., Japan and Germany,” Financial Markets, Institutions, and Instruments 4 (February 1995), Table 16.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

shares held by other companies and 35 with blocks owned by families. Only 26

of the companies did not have a substantial block of stock held by some company

or institution.

42

Note also the bank ownership of Daimler-Benz. This would be impossible in the

United States, where federal law prohibits equity investments by banks in nonfi-

nancial corporations. Germany’s universal banking system allows such invest-

ments. Moreover, German banks customarily hold shares for safekeeping on behalf

of individual and institutional investors and often acquire proxies to vote these

shares on the investors’ behalf. For example, Deutsche Bank held 28 percent of

Daimler-Benz for its own account and had proxies for 14 percent more. Therefore

it voted 42 percent, which approaches a majority.

The ownership structures illustrated in Figure 34.3 are common for large Ger-

man corporations. Control rests mainly with banks and blockholders, not with or-

dinary stockholders. Corporate control is achieved by buying or assembling blocks

of shares. When control changes, selling blockholders receive premiums of 9 to 16

percent over the trading price of the shares. That price increases by 2 or 3 percent

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 983

Daimler-Benz AG

Kuwait

Government

Mercedes

Automobil

Holding AG

Deutsche

Bank

Widely

held

Stern Automobil

Beteiligungsges.

mbH

Stella Automobil

Beteiligungsges.

mbH

Widely

held

Widely

held

Robert Bosch

GmbH

Komet Automobil

Beteiligungsges.

mbH

Bayerische

Landesbank

Dresdner

Bank

28.3% 14% 25.23%

25%

25% 25%25%25%

50%

about 300,000

shareholders

25%

32.37%

FIGURE 34.3

Ownership of

Daimler-Benz, 1990.

Source: J. Franks and C.

Mayer, “The Ownership

and Control of German

Corporations,” Review

of Financial Studies 14

(Winter 2001), Figure 1,

p. 949.

42

See J. Franks and C. Mayer, “The Ownership and Control of German Corporations,” Review of Finan-

cial Studies 14 (Winter 2001), Table 1, p. 947. A block was defined as at least 25 percent ownership. In

Germany, a block of this size can veto certain corporate actions, including share issues and changes in

corporate charters.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

only, so the gains to ordinary stockholders from changes in control are small.

43

In

the United States, by contrast, the big winners in acquisitions are usually the sell-

ing firm’s ordinary stockholders.

Blockholders in Germany do not have unchecked power, however. Large Ger-

man companies have two boards of directors: the supervisory board (Aufsichtsrat)

and management board (Vorstand). Half of the supervisory board’s members are

elected by employees, including management and staff as well as labor unions. The

other half represents stockholders, often including bank executives. (There is also

a chairman who can cast tie-breaking votes if necessary.) The supervisory board

oversees strategy and elects and monitors the management board which operates

the company. Thus control of shares does not mean control of the company—100

percent ownership controls only half of the supervisory board.

This two-tier governance structure reflects a belief, widespread in Europe, that

the firm should act in the interests of all its stakeholders, including its employees

and the public at large, and not just seek to maximize shareholder value. This struc-

ture does not mean poor financial performance or an easy life for management—

poor performance leads to management turnover, just as in the United States,

44

and the German economy has, in general, thrived over the last 50 years. One may

ask, however, whether German companies which undertake extensive interna-

tional operations, and seek financing in international capital markets, are best

served by a financial architecture that skimps on protection for outside minority

investors and discourages attempts to maximize the market value of the firm.

Daimler-Benz, now DaimlerChrysler, is an interesting case study. In the mid-

1990s it reversed an unsuccessful diversification strategy that had led it into sev-

eral other industries, including aerospace and defense. In 1998 it took over

Chrysler. It listed its shares on the New York Stock Exchange and issued financial

statements conforming to U.S. accounting standards. It turned to international cap-

ital markets for financing, including a share issue in the U.S. At the same time

Deutsche Bank was reducing its stake in the company. DaimlerChrysler has for-

mally announced a commitment to increasing shareholder value.

. . . And in Japan

Japan’s system of corporate governance is in some ways in between the systems of

Germany and the United States and in other ways different from both.

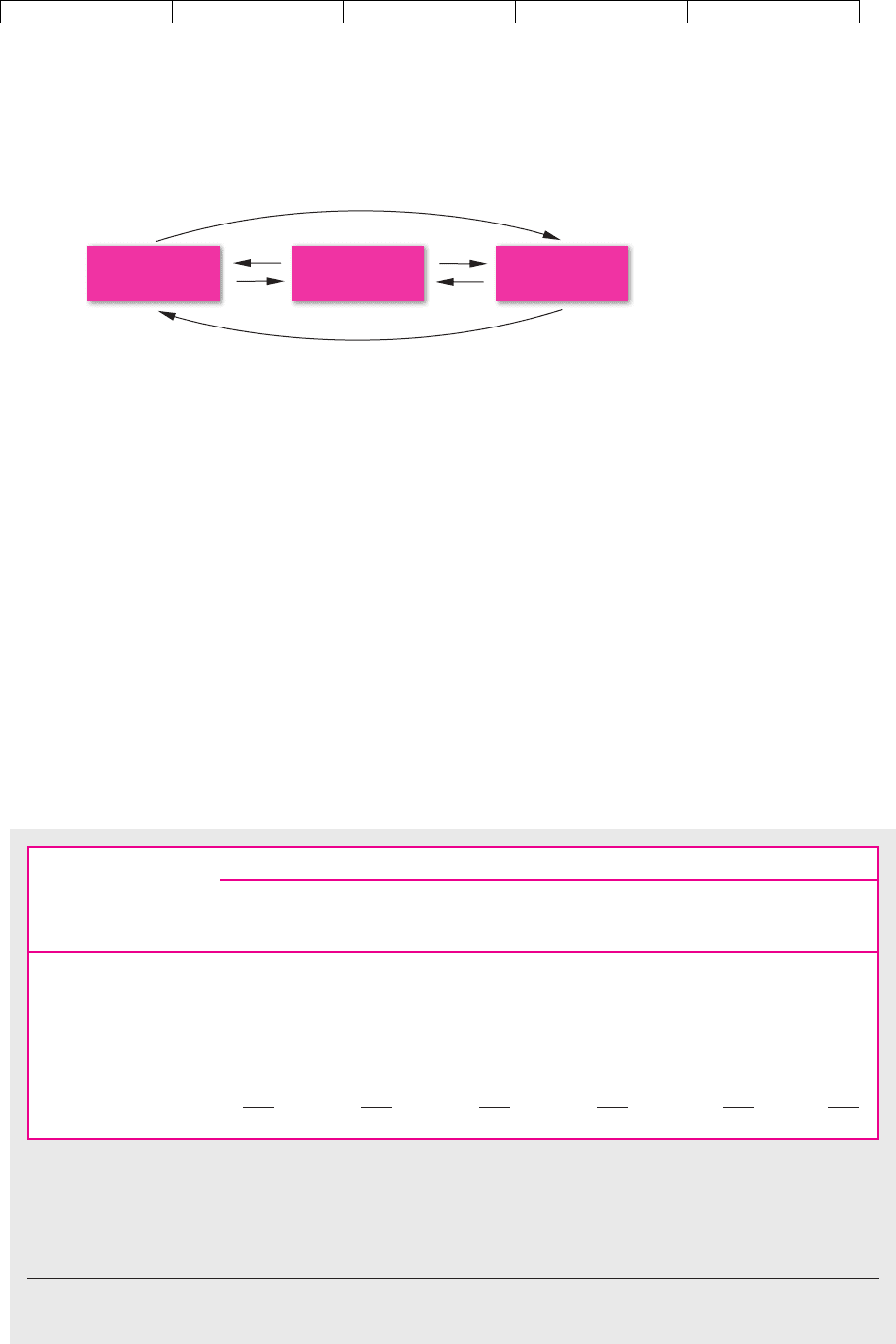

The most notable feature of Japanese corporate finance is the keiretsu. A

keiretsu is a network of companies, usually organized around a major bank. There

are long-standing business relationships between the group companies; a manu-

facturing company might buy a substantial part of its raw materials from group

suppliers and in turn sell much of its output to other group companies.

The bank and other financial institutions at the keiretsu’s center own shares in

most of the group companies (though a commercial bank in Japan is limited to 5

percent ownership of each company). Those companies may in turn hold the

bank’s shares or each others’ shares. Here are the cross-holdings at the end of 1991

between Sumitomo Bank; the Sumitomo Corporation, a trading company; and

Sumitomo Trust, which concentrates on investment management:

984 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

43

Franks and Mayer, op. cit., Table 9, p. 969.

44

See Franks and Mayer, op. cit.; and S. Kaplan, “Top Executives, Turnover and Firm Performance in

Germany,” Journal of Law and Economics 10 (1994), pp. 142–159.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Thus the bank owns 4.8 percent of Sumitomo Corporation, which owns 1.8 percent

of the bank. Both own shares in Sumitomo Trust . . . and so on. Table 34.5 illustrates

the myriad of cross-holdings in a keiretsu. Because of the cross-holdings, the sup-

ply of shares available for purchase by outside investors is much less than the to-

tal number outstanding.

The keiretsu is tied together in other ways. Most debt financing comes from the

keiretsu’s banks or from elsewhere in the group. (Until the mid-1980s, all but a hand-

ful of Japanese companies were forbidden access to public debt markets. The frac-

tion of debt provided by banks is still much greater than that in the United States.)

Managers may sit on the boards of directors of other group companies, and a “pres-

idents’ council” of the CEOs of the most important group companies meets regularly.

Think of the keiretsu as a system of corporate governance, where power is split be-

tween the main bank, the largest companies, and the group as a whole. This confers

certain financial advantages. First, firms have access to additional “internal” financ-

ing—internal to the group, that is. Thus a company with capital budgets exceeding

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 985

Sumitomo

Corporation

Sumitomo

Bank

Sumitomo

Trust

3.4%

5.9%

1.8%

4.8%

2.4%

3.4%

Percentage of Shares Held in:

Sumitomo

Sumitomo Metal Sumitomo Sumitomo Sumitomo

Shareholder Bank Industries Chemical Trust Corporation NEC

S. Bank — 4.1 4.6 3.4 4.8 5.0

S. Metal Industries * — * 2.5 2.8 *

S. Chemical * * — * * *

S. Trust 2.4 5.9 4.4 — 5.9 5.8

S. Corporation 1.8 1.6 * 3.4 — 2.2

NEC * * * 2.9 3.7 —

Other

†

9.7 4.8 9.8 10.4 9.5 11.6

Total

†

13.9 16.4 18.8 22.6 26.7 24.6

TABLE 34.5

Cross-holdings of common stock between six companies in the Sumitomo group in 1991. Read down the columns to see

holdings of each of the companies by the five others. Thus 4.6 percent of Sumitomo Chemical was owned by Sumitomo

Bank, 4.4 percent by Sumitomo Trust, and 9.8 percent by other Sumitomo companies. These figures were compiled by

examining the 10 largest shareholders of each company. Smaller cross-holdings are not reflected.

*

Cross-holding does not appear in the 10 largest shareholdings.

†

Based on the 10 largest shareholdings in 1991.

Source: Compiled from Dodwell Marketing Consultants, Industrial Groupings in Japan, 10th ed., Tokyo, 1992.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

operating cash flows can turn to the main bank or other keiretsu companies for fi-

nancing. This avoids the cost or possible bad-news signal of a public sale of securities.

Second, when a keiretsu firm falls into financial distress, with insufficient cash to pay

bills or fund necessary capital investments, a “workout” can usually be arranged.

New management can be brought in from elsewhere in the group, and financing can

be obtained, again “internally.”

Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein tracked capital expenditure programs of a large

sample of Japanese firms—many, but not all, members of keiretsus. The keiretsu

companies’ investments were more stable and less exposed to the ups and downs of

operating cash flows or to episodes of financial distress.

45

It seems that the financial

support of the keiretsus enabled their members to invest for the long run.

The Japanese system of corporate control has its disadvantages too, notably for

outside investors, who have very little influence. Japanese managers’ compensa-

tion is rarely tied to shareholder returns. Takeovers are unthinkable. Japanese com-

panies have been particularly stingy with cash dividends; this was hardly a con-

cern when growth was rapid and stock prices were stratospheric but is a serious

issue for the future.

Corporate Ownership around the World

The theory of modern finance is most readily applied to public corporations with

shares traded in active and efficient capital markets. The theory assumes that

stockholders’ interests are protected, so that ownership can be dispersed across

thousands of minority stockholders. The protection comes from managers’ incen-

tives, particularly compensation tied to stock price; from supervision by the board

of directors; and by the threat of hostile takeover of poorly performing companies.

This is a reasonable description of the corporate sector in the U.S., UK, and other

“Anglo-Saxon” countries such as Canada and Australia. But as Germany and

Japan illustrate, it is not an accurate description elsewhere. Corporate ownership

in Germany is typical of continental Europe. The ownership diagram for a large

French company would resemble Figure 34.3.

46

The financial architecture of public companies in “Anglo-Saxon” economies

may be the exception, not the rule. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer sur-

veyed the ownership of the largest companies in 27 developed countries. They

found that “except in economies with very good shareholder protection, relatively

few of these firms are widely held. Rather these firms are typically controlled by

families or the State,” or in some cases by financial institutions.

47

This finding has various possible interpretations. The first is obvious: Protection

for outside minority stockholders is a prerequisite for dispersed ownership and a

broad and active stock market. Second, in countries that lack effective legal pro-

tection for minority stockholders, concentrated ownership may be the only feasi-

ble financial architecture.

986 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

45

T. Hoshi, A. Kashyap, and D. Scharfstein, “Corporate Structure, Liquidity and Investment: Evidence

from Japanese Industrial Groups,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (February 1991), pp. 33–60, and

“The Role of Banks in Reducing the Costs of Financial Distress in Japan,” Journal of Financial Economics

27 (September 1990), pp. 67–88.

46

See J. Franks and C. Mayer, “Corporate Ownership and Control in the U. K., Germany and France,”

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 9 (Winter 1997), pp. 30–45.

47

R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer, “Corporate Ownership around the World,” Journal of

Finance 59 (April 1999), pp. 471–517.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We started with LBOs. An LBO is a takeover or buyout financed mostly with debt.

The LBO is owned privately, usually by an investment partnership. Debt financing

is not the objective of most LBOs; it is a means to an end. Most LBOs are diet deals.

The cash requirements for debt service force managers to shed unneeded assets,

improve operating efficiency, and forego wasteful capital expenditure. The man-

agers and key employees are given a significant equity stake in the business, so

they have strong incentives to make these improvements.

Leveraged restructurings are in many ways similar to LBOs. Large amounts of

debt are added and the proceeds are paid out. The company is forced to generate cash

to cover debt service, but there is no change in control and the company stays public.

Most investments in LBOs are made by private equity partnerships. We called

these temporary conglomerates. They are conglomerates because they assemble a

portfolio of companies in several unrelated industries. They are temporary because

the partnership has limited life, usually about 10 years. At the end of this period,

the partnership’s investments must be sold or taken public again in IPOs. Private

equity funds do not buy and hold; they buy, fix, and sell. Investors in the partner-

ship therefore do not have to worry about wasteful reinvestment of free cash flow.

LBO managers know that they will be able to cash out their equity stakes if their

company succeeds in improving efficiency and paying down debt.

The private equity partnership (or fund) is also common in venture capital and

other areas of private investment. The limited partners, who put up almost all of

the money, are mostly institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments,

and insurance companies. The limited partners are first in line when the partner-

ship’s investments are sold. The general partners, who organize and manage the

fund, get a carried interest in the fund’s profits.

The private equity market has been growing steadily. In contrast to these tempo-

rary conglomerates, public conglomerates have been declining in the United States.

In public companies, unrelated diversification seems to destroy value—the whole is

worth less than the sum of its parts. There are two possible reasons for this conglom-

erate discount. First, the value of the parts can’t be observed separately and it is diffi-

cult to set incentives for divisional managers. Second, conglomerates’ internal capital

markets are inefficient. It is difficult for management to appreciate investment op-

portunities in many different industries, and internal capital markets are prone to

overinvestment and cross-subsidies. The difficulties of running internal capital mar-

kets are not restricted to pure conglomerates, but they are most acute there.

Of course corporations shed assets as well as acquire them. Divisions are di-

vested by asset sales, carve-outs, or spin-offs. These divestitures are generally good

news to investors; it appears that the divisions are moving to better homes, where

they can be better managed and more profitable. The same improvements in effi-

ciency and profitability are observed in privatizations, which are spin-offs or

carve-outs of businesses owned by governments.

Although conglomerates are a declining species in the United States, they are

common elsewhere, particularly in emerging economies. An internal capital mar-

ket can make sense when a country’s financial markets are not well developed. Di-

versification also brings scale, which may make it easier to attract professional

management, to gain access to international financial markets, or to gain political

power in countries where the government tries to manage the economy or where

laws and regulations are erratically enforced.

We wonder, though, whether some of these emerging-market conglomerates

will be temporary rather than permanent. In a rapidly growing and modernizing

SUMMARY

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

988 PART X Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

economy, opportunities to buy and fix are spread across many industries. If these

investments are successful, the next logical step may be to sell and focus on one or

a few core businesses.

Our discussion of LBOs, private equity partnerships, and conglomerates illus-

trates how much financial architecture varies and how it depends on the financial

and business environment and on the task at hand. The conglomerate financial ar-

chitecture thrives in much of the world but not in the United States. LBOs are de-

signed to force change in mature businesses. Private equity partnerships eliminate

the separation of ownership and control and make sure that the general partners

have strong incentives to achieve high exit values for the partnership’s invest-

ments.

We also sketched typical arrangements for ownership and control in Germany

and Japan. We did so especially for readers in the United States, who may regard

their system as natural. In some circumstances the German or Japanese system can

work better. Here are two key differences.

First, corporate finance in the United States, Britain, and the other English-

speaking countries relies more on financial markets and less on banks or other fi-

nancial intermediaries than is the case in most other countries. United States cor-

porations routinely issue publicly traded debt in situations where Japanese or

European companies borrow from banks.

Second, U.S.-style corporate finance puts fewer buffers between managers and

the stock market. The block holdings and layered ownership structure of German

companies are rare in the United States, and of course there is nothing remotely like

a Japanese keiretsu. So CEOs and CFOs in the United States usually find their pay-

checks tied to stockholder returns. Negative returns may bring insomnia or bad

dreams about takeovers.

These international comparisons illustrate different approaches to the problem

of corporate governance—the problem of ensuring that managers act in share-

holders’ interest.

FURTHER

READING

Some of the ideas in this chapter were drawn from:

S. C. Myers: “Financial Architecture,” European Financial Management, 5:133–142 (July 1999).

The papers by Kaplan and by Kaplan and Stein provide evidence on the evolution and performance of

LBOs; Jensen, the chief proponent of the free-cash-flow theory of takeovers, gives a spirited and con-

troversial defense of LBOs:

S. N. Kaplan: “The Effects of Management Buyouts on Operating Performance and Value,”

Journal of Financial Economics, 24:217–254 (October 1989).

S. N. Kaplan and J. C. Stein: “The Evolution of Buyout Pricing and Financial Structure (Or, What

Went Wrong) in the 1980s,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 6:72–88 (Spring 1993).

M. C. Jensen: “The Eclipse of the Public Corporation,” Harvard Business Review, 67:61–74

(September/October 1989).

Privatization is reviewed in:

W. L. Megginson and J. M. Nutter: “From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on

Privatization,” Journal of Economic Literature, 39:321–389 (June 2001).

The Winter 1997 issue of the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance contains several articles on

governance and control in different countries. See also the following survey article:

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 34 Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 989

A. Shleifer and R. Vishny: “A Survey of Corporate Governance,” Journal of Finance,

52:737–783 (June 1997).

Here are five useful articles on corporate finance in Germany and Japan:

S. Prowse: “Corporate Governance in an International Perspective: A Survey of Corporate

Control Mechanisms among Large Firms in the U.S., U.K., Japan and Germany,” Financial

Markets, Institutions, and Investments, 4:1–63 (1995).

J. Franks and C. Mayer: “Ownership and Control of German Corporations,” Review of Fi-

nancial Studies, 14:943–977 (Winter 2001).

T. Jenkinson and A. Ljungqvist: “The Role of Hostile Stakes in German Corporate Perfor-

mance,” Journal of Corporate Finance, 7:397–446 (December 2001).

D. E. Logue and J. K. Seward: “Anatomy of a Governance Transformation: The Case of

Daimler-Benz,” Law and Contemporary Problems, 62:87–111 (Summer 1999).

E. Berglof and E. Perotti: “The Governance Structure of the Japanese Keiretsu,” Journal of Fi-

nancial Economics, 36:259–284 (October 1994).

Here are some interesting case studies pertinent to this chapter.

J. Allen: “Reinventing the Corporation: The Satellite Structure of Thermo Electron,” Journal

of Applied Corporate Finance, 11:38–47 (Summer 1998).

R. Parrino: “Spinoffs and Wealth Transfers: the Marriott Case,” Journal of Financial Econom-

ics, 43:241–274 (February 1997).

C. Eckel, D. Eckel, and V. Singal: “Privatization and Efficiency: Industry Effects of the Sale

of British Airways,” Journal of Financial Economics, 43:275–298 (February 1997).

B. Burrough and J. Helyar: Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco, Harper & Row, New

York, 1990.

G. P. Baker: “Beatrice: A Study in the Creation and Destruction of Value,” Journal of Finance,

47:1081–1120 (July 1992).

D. J. Denis: “Organizational Form and the Consequences of Highly Leveraged Transac-

tions,” Journal of Financial Economics, 36:193–224 (October 1994).

QUIZ

1. Define the following terms: (a) LBO, (b) MBO, (c) spin-off, (d) carve-out, (e) asset sale,

(f) privatization, and (g) leveraged restructuring.

2. True or false?

a. One of the first tasks of an LBO’s financial manager is to pay down debt.

b. Once an LBO or MBO goes private it almost always stays private.

c. Privatizations are generally followed by massive layoffs.

d. On average, privatization seems to improve efficiency and add value.

e. Targets for LBOs in the 1980s tended to be profitable companies in mature

industries.

f. “Carried interest” refers to the deferral of interest payments on LBO debt.

g. By the late 1990s, new LBO transactions were extremely rare.

3. What are the government’s motives in a privatization?

4. a. List the disadvantages of a traditional conglomerate in the United States.

b. What advantages might a conglomerate have in other countries, particularly less-

developed economies? List some examples.

5. What are the chief differences in the role of banks in corporate governance in the United

States, Germany, and Japan?

6. What is meant by a “temporary conglomerate”? Give an example.

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e