Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Any management team that tries to develop improved weapons of defense must

expect challenge in the courts. In the early 1980s the courts tended to give man-

agers the benefit of the doubt and respect their business judgment about whether

a takeover should be resisted. But the courts’ attitudes to takeover battles have

changed. For example, in 1993 a court blocked Viacom’s agreed takeover of Para-

mount on the grounds that Paramount’s directors did not do their homework be-

fore turning down a higher offer from QVC. Paramount was forced to give up its

poison-pill defense and the stock options that it had offered to Viacom. Because of

such decisions, managers have become much more careful in opposing bids, and

they do not throw themselves blindly into the arms of any white knight.

32

At the same time, state governments have provided some new defensive

weapons. In 1987 the Supreme Court upheld state laws that allow companies to de-

prive an investor of voting rights as soon as the investor’s share in the company ex-

950 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

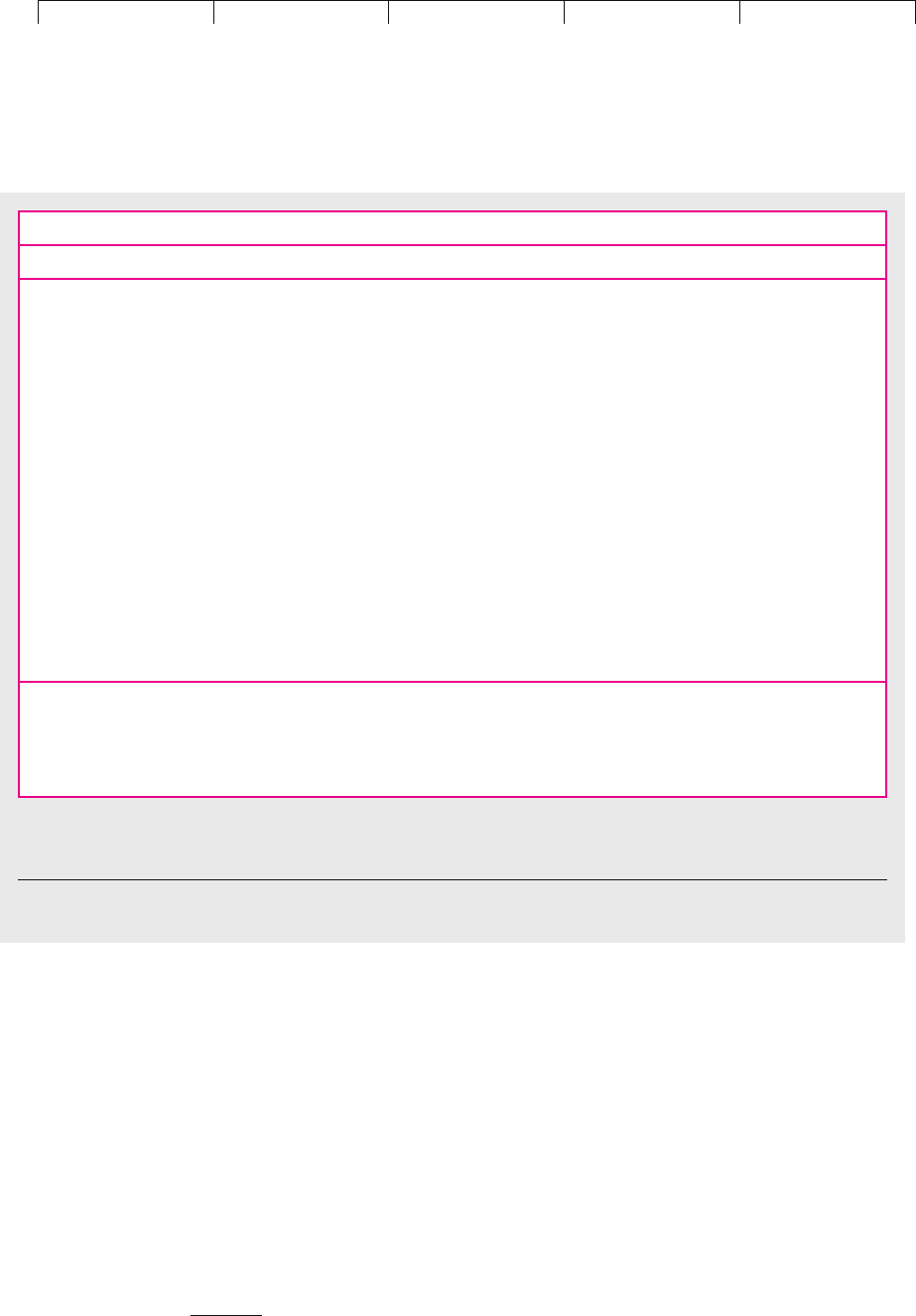

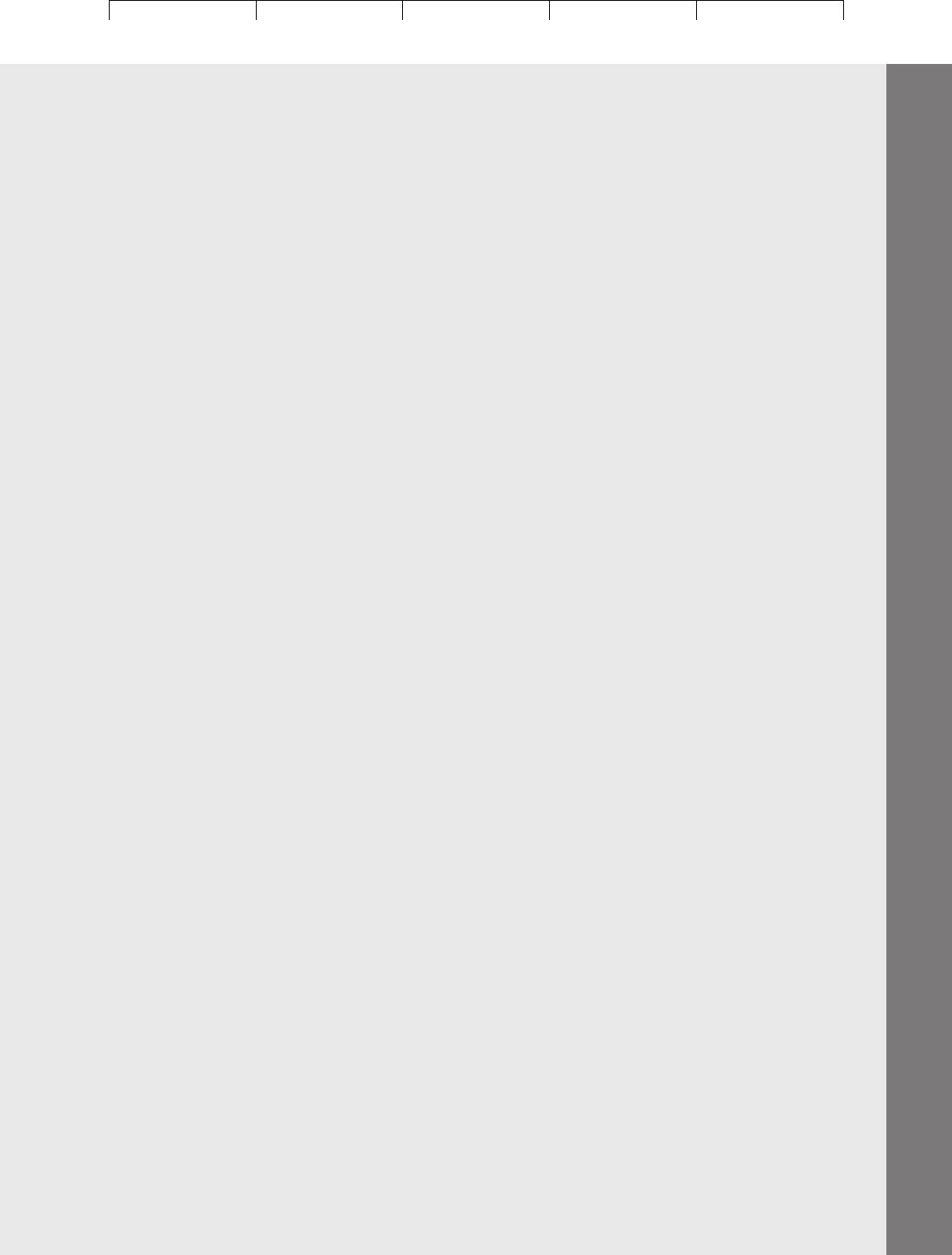

Type of Defense Description

Preoffer Defenses

Shark-repellent charter amendments:

Staggered board The board is classified into three equal groups. Only one group

is elected each year. Therefore the bidder cannot gain control

of the target immediately.

Supermajority A high percentage of shares is needed to approve a merger,

typically 80%.

Fair price Mergers are restricted unless a fair price (determined by formula

or appraisal) is paid.

Restricted Shareholders who own more than a specified proportion of the

voting rights target have no voting rights unless approved by the target’s board.

Waiting period Unwelcome acquirers must wait for a specified number of years

before they can complete the merger.

Other:

Poison pill Existing shareholders are issued rights which, if there is a significant

purchase of shares by a bidder, can be used to purchase additional

stock in the company at a bargain price.

Poison put Existing bondholders can demand repayment if there is a change of

control as a result of a hostile takeover.

Postoffer Defenses

Litigation File suit against bidder for violating antitrust or securities laws.

Asset restructuring Buy assets that bidder does not want or that will create an antitrust

problem.

Liability restructuring Issue shares to a friendly third party or increase the number of share-

holders. Repurchase shares from existing shareholders at a premium.

TABLE 33.6

A summary of takeover defenses.

Source: This table is loosely adapted from R. S. Ruback, “An Overview of Takeover Defenses,” working paper no. 1836–86, Sloan School

of Management, MIT, Cambridge, MA, September 1986, tables 1 and 2. See also L. Herzel and R. W. Shepro, Bidders and Targets:

Mergers and Acquisitions in the U.S., Basil Blackwell, Inc., Cambridge, MA, 1990, chap. 8.

32

In 1985 a shiver ran through many boardrooms when the directors of Trans Union Corporation were

held personally liable for being too hasty in accepting a takeover bid. Changes in judicial attitudes to

takeover defenses are reviewed in L. Herzel and R. W. Shepro, Bidders and Targets: Mergers and Acquisi-

tions in the U.S., Basil Blackwell, Inc., Cambridge, MA, 1990.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

ceeds a certain level. Since then state antitakeover laws have proliferated. Many al-

low boards of directors to block mergers with hostile bidders for several years and

to consider the interests of employees, customers, suppliers, and their communities

in deciding whether to try to block a hostile bid.

AlliedSignal vs. AMP

The hostile attacks of the 1980s were rarely repeated in the 1990s, when most merg-

ers were friendly.

33

But now and then a battle flared up. The following example il-

lustrates takeover tactics and defenses near the end of the millennium.

In the first week of August 1998, AlliedSignal, Inc., announced that it would bid

$44.50 per share, or $9.8 billion, for AMP, Inc. AMP’s stock price immediately

jumped by nearly 50 percent to about $43 per share.

AMP was the world’s largest producer of cables and connectors for computers and

other electronic equipment. It had just announced a fall of nearly 50 percent in quar-

terly profits from the previous year. The immediate cause for this bad news was eco-

nomic troubles in Southeast Asia, one of AMP’s most important export markets. But

longer-run performance had also disappointed investors, and the company was widely

viewed as ripe for change in operations and management. AlliedSignal was betting that

it could make these changes faster and better than the incumbent management.

AMP at first seemed impregnable. It was chartered in Pennsylvania, which had

passed tough antitakeover laws. Pennsylvania corporations could “just say no” to

takeovers that might adversely affect employees and local communities. The com-

pany also had a strong poison pill.

34

AlliedSignal held out an olive branch, hinting that price was flexible if AMP was

ready to talk turkey. But the offer was rebuffed. A tender offer went out to AMP share-

holders, and 72 percent accepted. However, the terms of the offer did not require

AlliedSignal to buy any shares until the poison pill was removed. In order to do that,

AlliedSignal would have to appeal again to AMP’s shareholders, asking them to ap-

prove a solicitation of consent blocking AMP’s directors from enforcing the pill.

AMP fought back vigorously and imaginatively. It announced a plan to borrow $3

billion to repurchase its shares at $55 per share—its management’s view of the true

value of AMP stock. It convinced a federal court to delay AlliedSignal’s solicitation of

consent. At the same time it asked the Pennsylvania legislature to pass a law which

would effectively bar the merger. The governor announced his support. Both compa-

nies sent teams of lobbyists to the state capitol. In October the bill was approved in

the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and sent to the Senate for consideration.

Yet AlliedSignal discovered it had powerful allies. About 80 percent of AMP’s

shares were owned by mutual funds, pension funds, and other institutional in-

vestors. Many of these institutions bluntly and publicly disagreed with AMP’s in-

transigence. The College Retirement Equities Fund (CREF), one of the largest U.S.

pension funds, called AMP’s defensive tactics “entirely inimical to the principles of

shareholder democracy and good corporate governance.” CREF then took an

extraordinary step: It filed a legal brief supporting AlliedSignal’s case in the federal

court.

35

Then the Hixon family, descendants of AMP’s co-founder, made public a

CHAPTER 33

Mergers 951

33

By contrast, a number of hostle takeovers took place in continental European countries where such

activity had been almost unknown.

34

It was a dead-hand poison pill: Even if AlliedSignal gained a majority of AMP’s board of directors, only

the previous directors were empowered to vote to remove the pill.

35

G. Faircloth, “AMP’s Tactics Against AlliedSignal Bid Are Criticized by Big Pension Fund,” The Wall

Street Journal, September 28, 1998, p. A17.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

letter to AMP’s management and directors expressing “dismay,” and asking, “Who

do management and the board work for? The central issue is that AMP’s manage-

ment will not permit shareholders to voice their will.”

36

AMP had complained all along that AlliedSignal’s bid was too low. Robert Ripp,

AMP’s chairman, reiterated this point in his reply to the Hixons and also said, “As

a board, we have an overarching responsibility to AMP, all of its shareholders, and

its other constituencies—which we believe we are serving on a basis consistent

with your interests.”

37

But as the weeks passed, AMP’s defenses, while still intact, did not look quite so

strong. By mid-October it became clear that AMP would not receive timely help from

the Pennsylvania legislature. In November, the federal court finally gave AlliedSignal

the go-ahead for its solicitation of consent to remove the poison pill. Remember,

72 percent of its stockholders had already accepted AlliedSignal’s tender offer.

Then, suddenly, AMP gave up: It agreed to be acquired by a white knight, Tyco

International, for $55 per AMP share, paid for in Tyco stock. AlliedSignal dropped

out of the bidding; it didn’t think AMP was worth that much.

What are the lessons? First is the strength of poison pills and other takeover de-

fenses, especially in a state like Pennsylvania where the law leans in favor of local

targets. AlliedSignal’s offensive gained ground, but with great expense and effort

and at a very slow pace.

The second lesson is the potential power of institutional investors. We believe

AMP gave in not because its legal and procedural defenses failed but largely be-

cause of economic pressure from its major shareholders.

Did AMP’s management and board act in shareholders’ interests? In the end,

yes. They said that AMP was worth more than AlliedSignal’s offer, and they found

another buyer to prove them right. However, they would not have searched for a

white knight absent AlliedSignal’s bid.

Who Gains Most in Mergers?

As our brief history illustrates, in mergers sellers generally do better than buyers. An-

drade, Mitchell, and Stafford found that following the announcement of the bid, sell-

ing shareholders received a healthy gain averaging 16 percent.

38

On the other hand,

it appears that investors expected acquiring companies to just about break even. The

prices of their shares fell by .7 percent.

39

The value of the total package—buyer plus

seller—increased by 1.8 percent. Of course, these are averages; selling shareholders

sometimes obtain much higher returns. When IBM took over Lotus Corporation, it

paid a premium of 100 percent, or about $1.7 billion, for Lotus stock.

Why do sellers earn higher returns? There are two reasons. First, buying firms

are typically larger than selling firms. In many mergers the buyer is so much larger

that even substantial net benefits would not show up clearly in the buyer’s share

price. Suppose, for example, that company A buys company B, which is only one-

tenth A’s size. Suppose the dollar value of the net gain from the merger is split

952 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

36

S. Lipin and G. Faircloth, “AMP’s Antitakeover Tactics Rile Holder,” The Wall Street Journal, October 5,

1998, p. A18.

37

Ibid.

38

See G. Andrade, M. Mitchell, and E. Stafford, “New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers,” Journal

of Economic Perspectives 15 (Spring 2001), pp. 103–120.

39

The small loss to the shareholders of acquiring firms is not statistically significant. Other studies us-

ing different samples have observed a small positive return.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

equally between A and B.

40

Each company’s shareholders receive the same dollar

profit, but B’s receive 10 times A’s percentage return.

The second, and more important, reason is the competition among potential

bidders. Once the first bidder puts the target company “in play,” one or more ad-

ditional suitors often jump in, sometimes as white knights at the invitation of the

target firm’s management. Every time one suitor tops another’s bid, more of the

merger gain slides toward the target. At the same time, the target firm’s manage-

ment may mount various legal and financial counterattacks, ensuring that capitu-

lation, if and when it comes, is at the highest attainable price.

Of course, bidders and targets are not the only possible winners. Unsuccessful

bidders often win, too, by selling off their holdings in target companies at sub-

stantial profits.

Other winners include investment bankers, lawyers, accountants, and in some

cases arbitrageurs, or “arbs,” who speculate on the likely success of takeover bids.

41

“Speculate” has a negative ring, but it can be a useful social service. A tender offer

may present shareholders with a difficult decision. Should they accept, should they

wait to see if someone else produces a better offer, or should they sell their stock in

the market? This dilemma presents an opportunity for the arbitrageurs, who spe-

cialize in answering such questions. In other words, they buy from the target’s share-

holders and take on the risk that the deal will not go through.

As Ivan Boesky demonstrated, arbitrageurs can make even more money if they

learn about the offer before it is publicly announced. Because arbitrageurs may ac-

cumulate large amounts of stock, they can have an important effect on whether a

deal goes through, and the bidding company or its investment bankers may be

tempted to take the arbitrageurs into their confidence. This is the point at which a

legitimate and useful activity becomes an illegal and harmful one.

CHAPTER 33

Mergers 953

40

In other words, the cost of the merger to A is one-half the gain .

41

Strictly speaking, an arbitrageur is an investor who takes a fully hedged, that is, riskless, position. But

arbitrageurs in merger battles often take very large risks indeed. Their activities are oxymoronicly

known as “risk arbitrage.”

∆PV

AB

33.6 MERGERS AND THE ECONOMY

Merger Waves

Mergers come in waves. The first episode of intense merger activity occurred at the

turn of the 20th century and the second occurred in the 1920s. There was a further

boom from 1967 to 1969 and then again in the 1980s and 1990s (1999 and 2000 were

record years). Each episode coincided with a period of buoyant stock prices,

though there were substantial differences in the types of companies that merged

and the ways they went about it.

We don’t really understand why merger activity is so volatile. If mergers are

prompted by economic motives, at least one of these motives must be “here to-

day and gone tomorrow,” and it must somehow be associated with high stock

prices. But none of the economic motives that we review in this chapter has any-

thing to do with the general level of the stock market. None burst on the scene in

1967, departed in 1970, and reappeared for most of the 1980s and again in the

mid-1990s.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Some mergers may result from mistakes in valuation on the part of the stock mar-

ket. In other words, the buyer may believe that investors have underestimated the

value of the seller or may hope that they will overestimate the value of the combined

firm. But we see (with hindsight) that mistakes are made in bear markets as well as

bull markets. Why don’t we see just as many firms hunting for bargain acquisitions

when the stock market is low? It is possible that “suckers are born every minute,” but

it is difficult to believe that they can be harvested only in bull markets.

Merger activity tends to be concentrated in a relatively small number of industries

and is often prompted by deregulation and by changes in technology or the pattern

of demand. Take the merger wave of the 1990s, for example. Deregulation of telecoms

and banking earlier in the decade led to a spate of mergers in both industries. Else-

where, the decline in military spending brought about a number of mergers between

defense companies until the Department of Justice decided to call a halt. And in the

entertainment industry the prospective advantages from controlling both content and

distribution led to mergers between such giants as AOL and Time Warner.

Do Mergers Generate Net Benefits?

There are undoubtedly good acquisitions and bad acquisitions, but economists

find it hard to agree on whether acquisitions are beneficial on balance. Indeed, since

there seem to be transient fashions in mergers, it would be surprising if economists

could come up with simple generalizations.

We do know that mergers generate substantial gains to acquired firms’ stock-

holders. Since buyers roughly break even and sellers make substantial gains, it

seems that there are positive overall benefits from mergers.

42

But not everybody is

convinced. Some believe that investors analyzing mergers pay too much attention

to short-term earnings gains and don’t notice that these gains are at the expense of

long-term prospects.

43

Since we can’t observe how companies would have fared in the absence of a

merger, it is difficult to measure the effects on profitability. Ravenscroft and Scherer,

who looked at mergers during the 1960s and early 1970s, argued that productivity de-

clined in the years following a merger.

44

But studies of subsequent merger activity

suggest that mergers do seem to improve real productivity. For example, Paul Healy,

Krishna Palepu, and Richard Ruback examined 50 large mergers between 1979 and

1983 and found an average increase of 2.4 percentage points in the companies’ pretax

954 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

42

M. C. Jensen and R. S. Ruback, “The Market for Corporate Control: The Scientific Evidence,” Journal

of Financial Economics 11 (April 1983), pp. 5–50, after an extensive review of empirical work, conclude

that “corporate takeovers generate positive gains” (p. 47). Richard Roll reviewed the same evidence and

argues that “takeover gains may have been overestimated if they exist at all.” See “The Hubris Hy-

pothesis of Corporate Takeovers,” Journal of Business 59 (April 1986), pp. 198–216.

43

There have been a number of attempts to test whether investors are myopic. For example, McConnell

and Muscarella examined the reaction of stock prices to announcements of capital expenditure plans.

If investors were interested in short-term earnings, which are generally depressed by major capital ex-

penditure programs, then these announcements should depress stock price. But they found that in-

creases in capital spending were associated with increases in stock prices and reductions were associ-

ated with falls. Similarly, Jarrell, Lehn, and Marr found that announcements of expanded R&D spending

prompted a rise in stock price. See J. McConnell and C. Muscarella, “Corporate Capital Expenditure De-

cisions and the Market Value of the Firm,” Journal of Financial Economics 14 (July 1985), pp. 399–422; and

G. Jarrell, K. Lehn, and W. Marr, “Institutional Ownership, Tender Offers, and Long-Term Investments,”

Office of the Chief Economist, Securities and Exchange Commission (April 1985).

44

See D. J. Ravenscroft and F. M. Scherer, “Mergers and Managerial Performance,” in J. C. Coffee, Jr., L.

Lowenstein, and S. Rose-Ackerman (eds.), Knights, Raiders, and Targets: The Impact of the Hostile Takeover,

Oxford University Press, New York, 1988.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 33 Mergers 955

returns.

45

They argue that this gain came from generating a higher level of sales from

the same assets. There was no evidence indicating that the companies were mortgag-

ing their long-term future by cutting back on long-term investments; expenditures on

capital equipment and research and development tracked industry averages.

46

Perhaps the most important effect of acquisitions is felt by the managers of com-

panies that are not taken over. Perhaps the threat of takeover spurs the whole of

corporate America to try harder. Unfortunately, we don’t know whether, on bal-

ance, the threat of merger makes for active days or sleepless nights.

The threat of takeover may be a spur to inefficient management, but it is also costly.

It can soak up large amounts of management time and effort. When a company is

planning a takeover, it can be difficult to pay as much attention as one should to the

firm’s existing business.

47

In addition, the company needs to pay for the services pro-

vided by the investment bankers, lawyers, and accountants. In the year 2000 merging

companies paid in total more than $2 billion for professional assistance.

45

See P. Healy, K. Palepu, and R. Ruback, “Does Corporate Performance Improve after Mergers?” Jour-

nal of Financial Economics 31 (April 1992), pp. 135–175. The study examined the pretax returns of the

merged companies relative to industry averages. A study by Lichtenberg and Siegel came to similar

conclusions. Before merger, acquired companies had lower levels of productivity than did other firms

in their industries, but by seven years after the control change, two-thirds of the productivity gap had

been eliminated. See F. Lichtenberg and D. Siegel, “The Effect of Control Changes on the Productivity

of U.S. Manufacturing Plants,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 2 (Summer 1989), pp. 60–67.

46

Maintained levels of capital spending and R&D are also observed by Lichtenberg and Siegel, op. cit.;

and B. H. Hall, “The Effect of Takeover Activity on Corporate Research and Development,” in A. J.

Auerbach (ed.), Corporate Takeover: Causes and Consequences, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1988.

47

There is some evidence that, while acquisitions lead to improvements in the productivity of the new

plant, productivity in the firm’s existing plant languishes. See R. McGuckin and S. Nguyen, “On Pro-

ductivity and Plant Ownership Change: New Evidence from the Longitudinal Research Database,”

Rand Journal of Economics 26 (1995), pp. 257–276.

SUMMARY

A merger generates an economic gain if the two firms are worth more together than

apart. Suppose that firms A and B merge to form a new entity, AB. Then the gain

from the merger is

Gains from mergers may reflect economies of scale, economies of vertical integra-

tion, improved efficiency, the combination of complementary resources, or rede-

ployment of surplus funds. In other cases there may be no advantage in combining

two businesses, but the object of the acquisition is to install a more efficient man-

agement team. There are also dubious reasons for mergers. There is no value added

by merging just to diversify risks, to reduce borrowing costs, or to pump up earn-

ings per share.

In many cases the object of merging is to replace management or to force changes

in investment or financing policies. Many of the takeovers in the 1980s were diet

deals, in which companies were forced to sell assets, cut costs, or reduce capital ex-

penditures. The changes added value when the target company had ample free cash

flow but was overinvesting or not trying hard enough to reduce costs or dispose of

underutilized assets.

You should go ahead with the acquisition if the gain exceeds the cost. Cost is the

premium that the buyer pays for the selling firm over its value as a separate entity.

It is easy to estimate when the merger is financed by cash. In that case,

Gain PV

AB

1PV

A

PV

B

2 ∆PV

AB

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

956 PART X Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

When payment is in the form of shares, the cost naturally depends on what those

shares are worth after the merger is complete. If the merger is a success, B’s stock-

holders will share the merger gains.

The mechanics of buying a firm are much more complex than those of buying a

machine. First, you have to make sure that the purchase does not fall afoul of the an-

titrust laws. Second, you have a choice of procedures: You can merge all the assets

and liabilities of the seller into those of your own company; you can buy the stock of

the seller rather than the company itself; or you can buy the individual assets of the

seller. Third, you have to worry about the tax status of the merger. In a tax-free

merger the tax position of the corporation and the stockholders is not changed. In a

taxable merger the buyer can depreciate the full cost of the tangible assets acquired,

but tax must be paid on any write-up of the assets’ taxable value, and the stock-

holders in the selling corporation are taxed on any capital gains.

Mergers are often amicably negotiated between the management and directors

of the two companies; but if the seller is reluctant, the would-be buyer can decide

to make a tender offer or engage in a proxy fight. We sketched some of the offen-

sive and defensive tactics used in takeover battles. We also observed that when the

target firm loses, its shareholders typically win: Selling shareholders earn large ab-

normal returns, while the bidding firm’s shareholders roughly break even. The

typical merger appears to generate positive net benefits for investors, but compe-

tition among bidders, plus active defense by target management, pushes most of

the gains toward the selling shareholders.

Cost cash paid PV

B

APPENDIX

Conglomerate Mergers and Value Additivity

A pure conglomerate merger is one that has no effect on the operations or prof-

itability of either firm. If corporate diversification is in stockholders’ interests, a

conglomerate merger would give a clear demonstration of its benefits. But if pres-

ent values add up, the conglomerate merger would not make stockholders better

or worse off.

In this appendix we examine more carefully our assertion that present values

add. It turns out that values do add as long as capital markets are perfect and in-

vestors’ diversification opportunities are unrestricted.

Call the merging firms A and B. Value additivity implies

where

value of combined firms just after merger;

market values of A and B just before merger.

For example, we might have

and

PV

B

$200 million 1$200 per share 1,000,000 shares outstanding2

PV

A

$100 million 1$200 per share 500,000 shares outstanding2

PV

A

, PV

B

separate

PV

AB

market

PV

AB

PV

A

PV

B

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 33 Mergers 957

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Suppose A and B are merged into a new firm, AB, with one share in AB exchanged for

each share of A or B. Thus there are 1,500,000 AB shares issued. If value additivity

holds, then must equal the sum of the separate values of A and B just before the

merger, that is, $300 million. That would imply a price of $200 per share of AB stock.

But note that the AB shares represent a portfolio of the assets of A and B. Before the

merger investors could have bought one share of A and two of B for $600. Afterward

they can obtain a claim on exactly the same real assets by buying three shares of AB.

Suppose that the opening price of AB shares just after the merger is $200, so that

. Our problem is to determine if this is an equilibrium price,

that is, whether we can rule out excess demand or supply at this price.

For there to be excess demand, there must be some investors who are willing to

increase their holdings of A and B as a consequence of the merger. Who could they

be? The only thing new created by the merger is diversification, but those investors

who want to hold assets of A and B will have purchased A’s and B’s stock before

the merger. The diversification is redundant and consequently won’t attract new

investment demand.

Is there a possibility of excess supply? The answer is yes. For example, there will

be some shareholders in A who did not invest in B. After the merger they cannot

invest solely in A, but only in a fixed combination of A and B. Their AB shares will

be less attractive to them than the pure A shares, so they will sell part of or all their

AB stock. In fact, the only AB shareholders who will not wish to sell are those who

happened to hold A and B in exactly a 1:2 ratio in their premerger portfolios!

Since there is no possibility of excess demand but a definite possibility of excess

supply, we seem to have

That is, corporate diversification can’t help, but it may hurt investors by restricting

the types of portfolios they can hold. This is not the whole story, however, since in-

vestment demand for AB shares might be attracted from other sources if

drops below . To illustrate, suppose there are two other firms, A* and

B*, which are judged by investors to have the same risk characteristics as A and B,

respectively. Then before the merger,

where r is the rate of return expected by investors. We’ll assume and

.

Consider a portfolio invested one-third in A* and two-thirds in B*. This portfo-

lio offers an expected return of 16 percent:

A similar portfolio of A and B before their merger also offered a 16 percent return.

As we have noted, a new firm AB is really a portfolio of firms A and B, with port-

folio weights of and . Thus it is equivalent in risk to the portfolio of and .

Thus the price of AB shares must adjust so that it likewise offers a 16 percent return.

What if AB shares drop below $200, so that is less than ? Since

the assets and earnings of firms A and B are the same, the price drop means that the

expected rate of return on AB shares has risen above the return offered by the

portfolio. That is, if exceeds , then must also exceed .

But this is untenable: Investors and could sell part of their holdings (in a 1:2 ra-

tio), buy AB, and obtain a higher expected rate of return with no increase in risk.

B*A*

1

/

3

r

A*

2

/

3

r

B*

r

AB

1

/

3

r

A

2

/

3

r

B

r

AB

A*B*

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

B*A*

2

/

3

1

/

3

1

/

3

1.082

2

/

3

1.202 .16

r x

A*

r

A*

x

B*

r

B*

r

B

r

B*

.20

r

A

r

A*

.08

r

A

r

A*

andr

B

r

B*

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

PV

AB

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

958 PART X Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

On the other hand, if rises above , the AB shares will offer an

expected return less than that offered by the portfolio. Investors will unload

the AB shares, forcing their price down.

A stable result occurs only if AB shares stick at $200. Thus, value additivity will

hold exactly in a perfect-market equilibrium if there are ample substitutes for the

A and B assets. If A and B have unique risk characteristics, however, then can

fall below . The reason is that the merger curtails investors’ opportunity

to custom-tailor their portfolios to their own needs and preferences. This makes in-

vestors worse off, reducing the attractiveness of holding the shares of firm AB.

In general, the condition for value additivity is that investors’ opportunity set—

that is, the range of risk characteristics attainable by investors through their port-

folio choices—is independent of the particular portfolio of real assets held by the

firm. Diversification per se can never expand the opportunity set given perfect se-

curity markets. Corporate diversification may reduce the investors’ opportunity

set, but only if the real assets the corporations hold lack substitutes among traded

securities or portfolios.

In a few cases the firm may be able to expand the opportunity set. It can do so

if it finds an investment opportunity that is unique—a real asset with risk charac-

teristics shared by few or no other financial assets. In this lucky event the firm

should not diversify, however. It should set up the unique asset as a separate firm

so as to expand investors’ opportunity set to the maximum extent. If Gallo by

chance discovered that a small portion of its vineyards produced wine comparable

to Chateau Margaux, it would not throw that wine into the Hearty Burgundy vat.

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

A*B*

PV

A

PV

B

PV

AB

FURTHER

READING

Here are two useful books on takeovers:

L. Herzel and R. Shepro: Bidders and Targets: Mergers and Acquisitions in the U.S., Basil Black-

well, Inc., Cambridge, MA, 1990.

J. F. Weston, K. S. Chung, and J. A. Siu: Takeovers, Restructuring and Corporate Finance, 3rd ed.,

Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2000.

A good review of the mechanics of acquisitions is provided in:

S. M. Litwin: “The Merger and Acquisition Process: A Primer on Getting the Deal Done,” The

Financier: ACMT, 2:6–17 (November 1995).

Recent merger waves are reviewed in:

G. Andrade, M. Mitchell, and E. Stafford: “New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers,”

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15:103–120 (Spring 2001).

Jensen and Ruback review the early empirical work on mergers. The April 1983 issue of the Journal of

Financial Economics also contains a collection of some of the more important empirical studies.

M. C. Jensen and R. S. Ruback: “The Market for Corporate Control: The Scientific Evidence,”

Journal of Financial Economics, 11:5–50 (April 1983).

Finally, here are some informative case studies:

G. P. Baker: “Beatrice: A Study in the Creation and Destruction of Value,” Journal of Finance,

47:1081–1119 (July 1992).

R. Bruner: “An Analysis of Value Destruction and Recovery in the Alliance and Proposed

Merger of Volvo and Renault,” Journal of Financial Economics, 51:125–166 (1999).

R. S. Ruback: “The Cities Service Takeover: A Case Study,” Journal of Finance, 38:319–330

(May 1983).

B. Burrough and J. Helyar: Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco, Harper & Row, New

York, 1990.

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

33. Mergers

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 33 Mergers 959

QUIZ

1. Are the following hypothetical mergers horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate?

a. IBM acquires Dell Computer.

b. Dell Computer acquires Kroger.

c. Kroger acquires H. J. Heinz.

d. H. J. Heinz acquires IBM.

2. Which of the following motives for mergers make economic sense?

a. Merging to achieve economies of scale.

b. Merging to reduce risk by diversification.

c. Merging to redeploy cash generated by a firm with ample profits but limited

growth opportunities.

d. Merging to combine complementary resources.

e. Merging just to increase earnings per share.

3. Velcro Saddles is contemplating the acquisition of Pogo Ski Sticks, Inc. The values of the

two companies as separate entities are $20 million and $10 million, respectively. Velcro

Saddles estimates that by combining the two companies, it will reduce marketing and

administrative costs by $500,000 per year in perpetuity. Velcro Saddles can either pay

$14 million cash for Pogo or offer Pogo a 50 percent holding in Velcro Saddles. The op-

portunity cost of capital is 10 percent.

a. What is the gain from merger?

b. What is the cost of the cash offer?

c. What is the cost of the stock alternative?

d. What is the NPV of the acquisition under the cash offer?

e. What is its NPV under the stock offer?

4. Which of the following transactions are not likely to be classed as tax-free?

a. An acquisition of assets.

b. A merger in which payment is entirely in the form of voting stock.

5. True or false?

a. Sellers almost always gain in mergers.

b. Buyers usually gain more than sellers.

c. Firms that do unusually well tend to be acquisition targets.

d. Merger activity in the United States varies dramatically from year to year.

e. On the average, mergers produce large economic gains.

f. Tender offers require the approval of the selling firm’s management.

g. The cost of a merger to the buyer equals the gain realized by the seller.

6. Mature companies with ample free cash flow are often targets for takeovers. Briefly ex-

plain why.

7. Briefly define the following terms:

a. Purchase accounting

b. Tender offer

c. Poison pill

d. Greenmail

e. White knight

PRACTICE

QUESTIONS

1. Examine several recent mergers and suggest the principal motives for merging in each case.

2. Examine a recent merger in which at least part of the payment made to the seller was

in the form of stock. Use stock market prices to obtain an estimate of the gain from the

merger and the cost of the merger.

3. Respond to the following comments.

a. “Our cost of debt is too darn high, but our banks won’t reduce interest rates as

long as we’re stuck in this volatile widget-trading business. We’ve got to acquire

other companies with safer income streams.”

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e