Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

970

Unix

System

Labs,

1991,1995

NCR,

1991

Teradata,

1991

AT&T

Capital,

1993, 1996

AT&T

Submarine

Systems,

1997

AT&T

Universal

Card,

1998

AT&T

Broadband,

2001

Lucent,

1996

NCR,

1996

McCaw

Cellular,

1994

LIN

Broadcasting,

1995

Global

Network

(from IBM),

1998, 1999

Media One,

2000

Vanguard

Cellular,

1999

TCI,

1999

At Home Corp.

(Excite@Home),

2000

Divestitures

Mergers and

Acquisitions

1984

Antitrust

Settlement

Ameritech

Bell Atlantic

Bell South

AT&T

NYNEX

Pacific

Telesis

Southwestern

Bell

U.S. West

AT&T

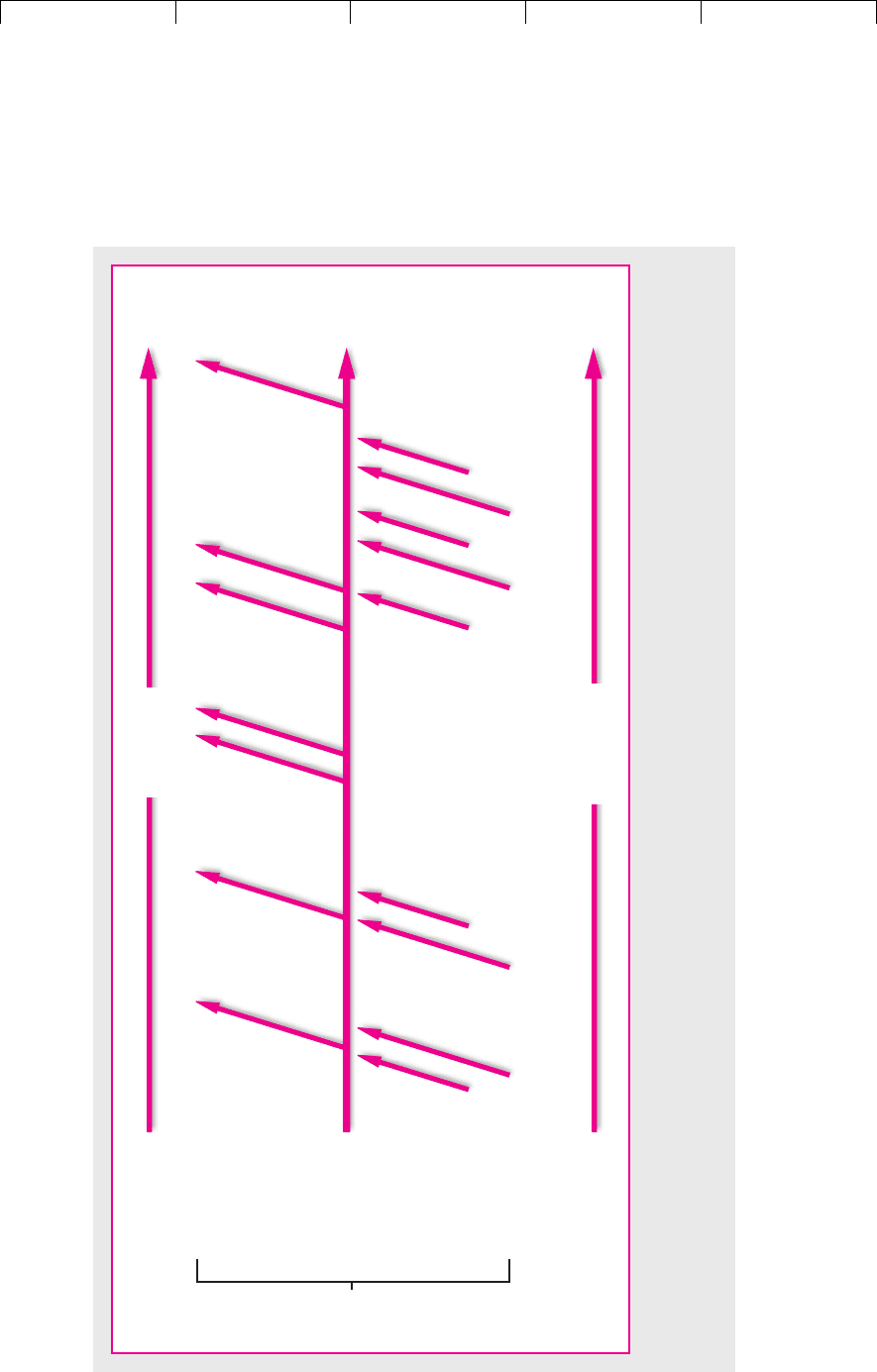

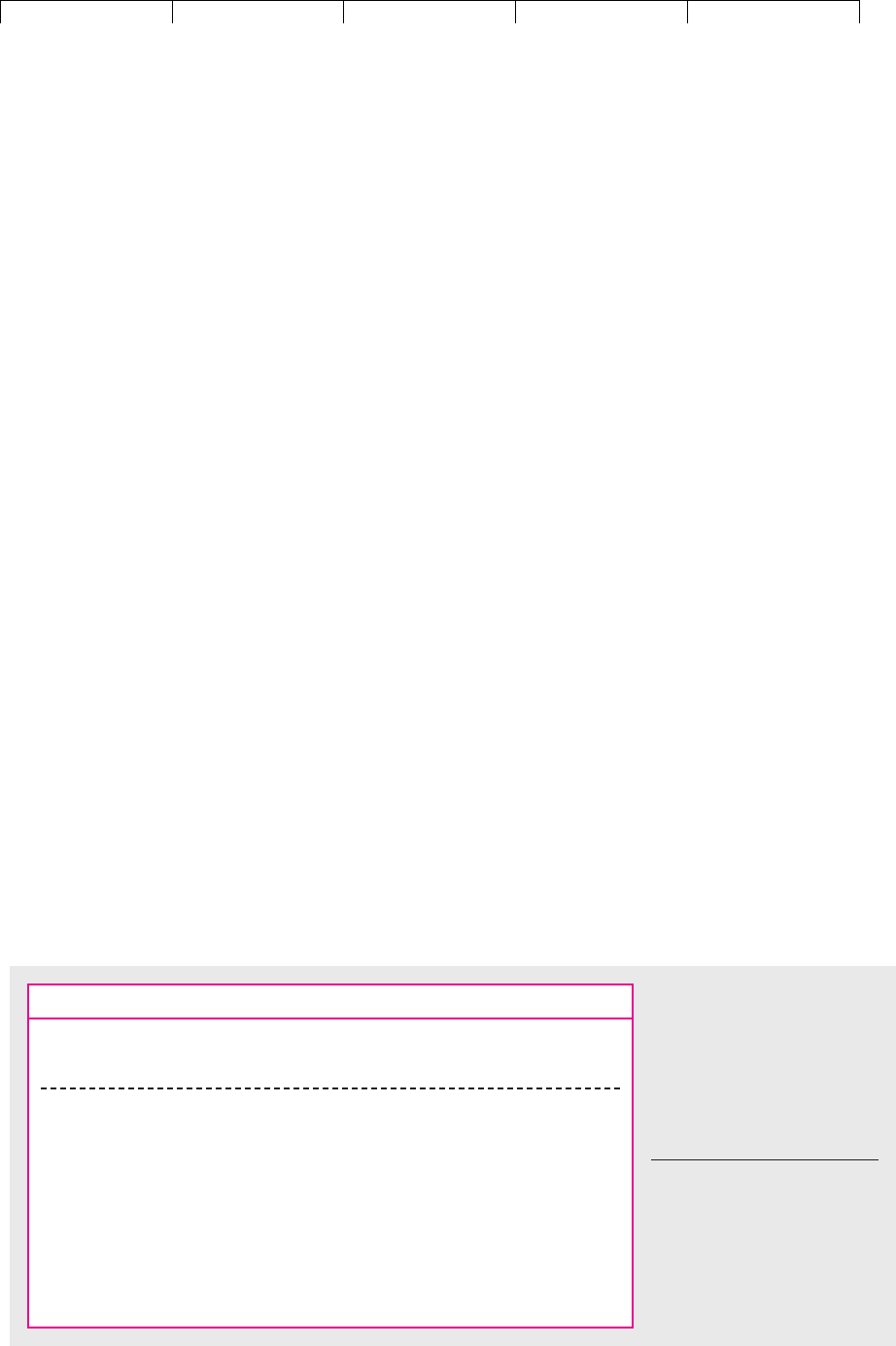

FIGURE 34.1

The effects of AT&T’s antitrust settlement in 1984, and a few of AT&T’s acquisitions and divestitures from 1991 to 2001. Divestitures are shown by the

outgoing burgundy arrows. When two years are given, the transaction was completed in two steps.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Spin-offs widen investors’ choice by allowing them to invest in just one part of

the business. More important, spin-offs can improve incentives for managers.

Companies sometimes refer to divisions or lines of business as “poor fits.” By spin-

ning these businesses off, management of the parent company can concentrate on

its main activity.

17

If the businesses are independent, it is easier to see the value and

performance of each and reward managers accordingly. Managers can be given

stock or stock options in the spun-off company. Also, spin-offs relieve investors of

the worry that funds will be siphoned from one business to support unprofitable

capital investments in another.

Announcement of a spin-off is generally greeted as good news by investors.

18

Investors in U.S. companies seem to reward focus and penalize diversification.

Consider the dissolution of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil trust in 1911. The

company he founded, Standard Oil of New Jersey, was split up into seven sep-

arate corporations. Within a year of the breakup, the combined value of the suc-

cessor companies’ shares had more than doubled, increasing Rockefeller’s per-

sonal fortune to about $900 million (about $15 billion in 2002 dollars). Theodore

Roosevelt, who as president had led the trustbusters, ran again for president

in 1912:

19

“The price of stock has gone up over 100 percent, so that Mr. Rockefeller and his as-

sociates have actually seen their fortunes doubled,” he thundered during the cam-

paign. “No wonder that Wall Street’s prayer now is: ‘Oh Merciful Providence, give

us another dissolution.’ ”

Why is the value of the parts so often greater than the value of the whole? The

best place to look for an answer to that question is in the financial architecture of

conglomerates. But first, we take a brief look at carve-outs, asset sales, and priva-

tizations.

Carve-outs

Carve-outs are similar to spin-offs, except that shares in the new company are not

given to existing shareholders but are sold in a public offering. Recent carve-outs

include Pharmacia’s sale of part of its Monsanto subsidiary, and Philip Morris’s

sale of part of its Kraft Foods subsidiary. The latter sale raised $8.7 billion.

Most carve-outs leave the parent with majority control of the subsidiary, usually

about 80 percent ownership.

20

This may not reassure investors who worry about

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 971

17

The other way of getting rid of “poor fits” is to sell them to another company. One study found that

over 30 percent of assets acquired in a sample of hostile takeovers from 1984 to 1986 were subsequently

sold. See S. Bhagat, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny, “Hostile Takeovers in the 1980s: The Return to Corporate

Specialization,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics (1990), pp. 1–12.

18

Research on spin-offs includes K. Schipper and A. Smith, “Effects of Recontracting on Shareholder

Wealth: The Case of Voluntary Spin-offs,” Journal of Financial Economics 12 (December 1983), pp. 409–436;

G. Hite and J. Owers, “Security Price Reactions around Corporate Spin-off Announcements,” Journal of

Financial Economics 12 (December 1983), pp. 437–467; and J. Miles and J. Rosenfeld, “An Empirical Analy-

sis of the Effects of Spin-off Announcements on Shareholder Wealth,” Journal of Finance 38 (December

1983), pp. 1597–1615. P. Cusatis, J. Miles, and J. R. Woolridge report improvements of operating per-

formance in spun-off companies. See “Some New Evidence that Spin-offs Create Value,” Journal of

Applied Corporate Finance 7 (Summer 1994), pp. 100–107.

19

D. Yergin: The Prize, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1991, p. 113.

20

The parent must retain an 80 percent interest to consolidate the subsidiary with the parent’s tax ac-

counts. Otherwise the subsidiary is taxed as a freestanding corporation.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

lack of focus or a poor fit, but it does allow the parent to set managers’ compensa-

tion based on the performance of the subsidiary’s stock price.

Some companies carve out a minority interest in a subsidiary and later sell or

spin off the remaining shares. For example, Sara Lee, the food company, carved

out a 19.5 percent stake in the luxury leather goods retailer Coach in 2000. The

remaining 80.5 percent of the Coach shares were sold to Sara Lee stockholders

in 2001.

21

Perhaps the most enthusiastic carver-outer of the 1980s and 1990s was Thermo

Electron, with operations in healthcare, power generation equipment, instrumen-

tation, environmental monitoring and cleanup, and various other areas. At year-

end 1997, it had seven publicly traded subsidiaries, which in turn had carved out

15 further public companies. The 15 were grandchildren of the ultimate parent,

Thermo Electron.

22

Some companies have distributed tracking stock tied to the performance of par-

ticular divisions. This does not require a spin-off or carve-out, only the creation of

a new class of common stock. For example, in 1997 Georgia Pacific distributed a

special class of shares tied to the performance of its Timber Group. The company

noted that having two classes of shares “provides the opportunity to structure in-

centives for employees of each Group that are tied directly to the share price per-

formance of that Group.”

23

Asset Sales

The simplest way to divest an asset is to sell it. Asset sale refers to the acquisition

of part of one firm by another. The record asset sale is Comcast’s acquisition of

AT&T Broadband, AT&T’s cable television division, for $42 billion in 2001.

We have mentioned the sale of AT&T’s credit card division to Citibank. Asset

sales are common in the credit card business. The largest credit card issuers, in-

cluding Citibank, MBNA, and First USA, grew during the 1980s and 1990s by ac-

quiring the credit card operations of hundreds of smaller banks.

Asset sales are also common in manufacturing. Maksimovic and Phillips exam-

ined a sample of about 50,000 U.S. manufacturing plants each year from 1974 to

1992. About 35,000 plants in the sample changed hands during that period. About

one-half of the ownership changes were the result of mergers or acquisitions of en-

tire firms. The other half of the ownership changes came about by asset sales, that

is, sale of part or all of a division. On average, about 4 percent of the plants in the

sample changed hands each year, about 2 percent by merger or acquisition, and

about 2 percent by asset sales.

24

972 PART X Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

21

Sara Lee stockholders were allowed to exchange Sara Lee shares for Coach shares. The terms of the

exchange gave Sara Lee’s stockholders the opportunity to get Coach shares at a discount, so all of the

Coach shares were issued in short order.

22

In 1998 Thermo Electron announced a plan to consolidate several of its children and grandchildren in

order to move to a less complicated structure. In 2001, it began to spin off some of its peripheral oper-

ations as separate companies.

23

Georgia Pacific Corporation, Proxy Statement and Prospectus, November 11, 1997, p. 35. The Timber

Group was sold to Plum Creek Timber Company in 2001. Timber Group tracking stock was exchanged

for Plum Creek shares.

24

V. Maksimovic and G. Phillips, “The Market for Corporate Assets: Who Engages in Mergers and As-

set Sales and Are There Efficiency Gains?” Journal of Finance 56 (December 2001), Table I, p. 2030.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Announcements of asset sales are good news for investors in the selling firm,

and productivity of the assets sold increases, on average, after the sale.

25

It appears

that asset sales transfer business units to the companies that can manage them

most effectively.

Privatization

A privatization is a sale of a government-owned company to private investors. For

example, the government of Germany originally owned Volkswagen but sold it in

1961. Britain sold British Telecom in 1984. The United States sold Conrail in 1987.

Most privatizations are more like carve-outs than spin-offs, because shares are

sold for cash, not distributed to the ultimate “shareholders,” that is, to the people

of the selling country. But several former Communist countries, including Russia,

Poland, and the Czech Republic, privatized by means of vouchers distributed to

citizens. The vouchers could be used to bid for shares in newly privatized compa-

nies. Thus the companies were not sold for cash, but for vouchers.

26

Privatizations raised enormous sums for selling governments. France raised

$17.6 billion in two share issues for France Telecom in 1997 and 1998. Japan raised

over $80 billion in the privatization of NTT (Nippon Telephone and Telegraph) in

1987 and 1988. Privatizations have also been common in airlines (e.g., Japan Air-

lines and Air New Zealand) and banking (e.g., the French bank Paribas).

The motives for privatization seem to boil down to the following three points:

1. Increased efficiency. Through privatization, the enterprise is exposed to the

discipline of competition and insulated from political influence on

investment and operating decisions. Managers and employees can be given

stronger incentives to cut costs and add economic value.

2. Share ownership. Privatizations encourage share ownership. Many

privatizations give special terms or allotments to employees or small

investors.

3. Revenue for the government. Last but not least!

There were fears that privatizations would lead to massive layoffs and unem-

ployment, but that does not appear to be the case. While it is true that privatized

companies operate more efficiently and thus reduce employment, they also grow

faster as privatized companies, which increases employment. In many cases the

net effect on employment is positive.

On other dimensions, the impact of privatization is almost always positive. A re-

view of research on privatization concludes that privatized firms “almost always

become more efficient, more profitable, . . . financially healthier and increase their

capital investment spending.”

27

It seems clear that changing from state to private

ownership is in general a valuable change in financial architecture.

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 973

25

See Maksimovic and Phillips, op. cit.

26

There is extensive research on voucher privatizations. See, for example, M. Boyco, A. Shleifer, and R.

Vishny, “Voucher Privatizations,” Journal of Financial Economics 35 (April 1994), pp. 249–266; and R. Ag-

garwal and J. T. Harper, “Equity Valuation in the Czech Voucher Privatization Auctions,” Financial Man-

agement 29 (Winter 2000), pp. 77–100.

27

W. L. Megginson and J. M. Netter, “From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privati-

zation,” Journal of Economic Literature 39 (June 2001), p. 381.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We now examine a different form of financial architecture, the conglomerate. Con-

glomerates are firms investing in several unrelated industries. Large public con-

glomerates are now rare in the United States, though common elsewhere. We will

try to figure out why. We will also examine the financial architecture of the private

conglomerates that invest in venture capital and LBOs.

Pros and (Mostly) Cons of U.S. Conglomerates

Conglomerates were the corporate celebrities of the 1960s. They grew by leaps and

bounds through aggressive programs of acquisitions in unrelated industries. By

the 1970s, the largest conglomerates had achieved amazing scopes and spans.

Table 34.2 shows that by 1979 ITT was operating in 38 different industries and

ranked eighth in total sales among U.S. corporations.

In 1995 ITT, which had already sold or spun off several lines of business, split its

remaining operations into three separate firms. One acquired ITT’s interests in ho-

tels and gambling; a second took over ITT’s automotive parts, defense, and elec-

tronics businesses; and a third specialized in insurance and financial services (ITT

Hartford). Most of the conglomerates created in the 1960s were broken up in the

1980s and early 1990s; however, a few successful new conglomerates have sprung

up. Tyco International, AMP’s white knight, is one of these.

28

What advantages were claimed for conglomerates? First, diversification across

industries was supposed to stabilize earnings and reduce risk. That’s hardly com-

pelling, because shareholders can diversify much more efficiently and flexibly on

their own.

29

Second, and more important, was the idea that good managers were

fungible; in other words, that modern management would work as well in the

manufacture of auto parts as in running a hotel chain. Neil Jacoby, writing in 1969,

argued that computers and new methods of quantitative, scientific management

had “created opportunities for profits through mergers that remove assets from the

974 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

34.3 CONGLOMERATES

Sales Rank Company Number of Industries

8 International Telephone & 38

Telegraph (ITT)

15 Tenneco 28

42 Gulf & Western Industries 41

51 Litton Industries 19

66 LTV 18

73 Illinois Central Industries 26

103 Textron 16

104 Greyhound 19

128 Martin Marietta 14

TABLE 34.2

The largest U.S. conglomerates in

1979, ranked by sales compared to

all U.S. industrial corporations.

Most of these companies have

been broken up.

Source: A. Chandler and R. S. Tetlow,

eds., The Coming of Managerial

Capitalism, Richard D. Irwin, Inc.,

Homewood, IL, 1985, p. 772; see also J.

Baskin and P. J. Miranti, Jr., A History of

Corporate Finance, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK: 1997,

chap. 7.

28

See Section 33.5.

29

See the Appendix to Chapter 33.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

inefficient control of old-fashioned managers and place them under men schooled

in the new management science.”

30

There was some truth in this. The most successful early conglomerates did force

dramatic improvements in some mature and slackly managed businesses. The

problem is, of course, that a company doesn’t need to be diversified to take over

and improve a lagging business.

Third, conglomerates’ wide diversification meant that their top managements

could operate an internal capital market. Free cash flow generated by divisions in

mature industries could be funneled within the company to other divisions with

profitable growth opportunities. There was no need for fast-growing divisions to

raise financing from outside investors.

There are some good arguments for internal capital markets. The company’s own

managers probably know more about its investment opportunities than do outside

investors, and transaction costs of issuing securities are avoided. Nevertheless, it ap-

pears that attempts by conglomerates to allocate capital investment across many un-

related industries are more likely to subtract value than add it. Trouble is, internal

capital markets are not really markets but combinations of central planning (by the

conglomerates’ top management and financial staff) and intracompany bargaining.

Divisional capital budgets depend on politics as well as pure economics. Large, prof-

itable divisions with plenty of free cash flow may have more bargaining power than

growth opportunities; they may get generous capital budgets while smaller divi-

sions with good prospects but less bargaining power are reined in.

Berger and Ofek estimate the average conglomerate discount at 12 to 15 per-

cent.

31

Conglomerate discount means that the market value of the whole conglomer-

ate is less than the sum of the values of its parts. The chief cause of this discount,

at least in Berger and Ofek’s sample, seemed to be overinvestment and misalloca-

tion of investment. In other words, investors were marking down the value of the

conglomerates’ shares from worry that their managements would make negative-

NPV investments in mature divisions and forego positive-NPV opportunities else-

where.

Conglomerates face further problems. Their divisions’ market values can’t be

observed independently, and it is difficult to set incentives for division managers.

This is particularly serious when managers are asked to commit to risky ventures.

For example, how would a biotech startup fare as a division of a traditional con-

glomerate? Would the conglomerate be as patient and risk-tolerant as investors in

the stock market? How are the scientists and clinicians doing the biotech R&D re-

warded if they succeed? We don’t mean to say that high-tech innovation and risk-

taking is impossible in public conglomerates, but the difficulties are evident.

Internal Capital Markets in the Oil Business Misallocations in internal capital

markets are not restricted to pure conglomerates. For example, Lamont found that,

when oil prices fell by half in 1986, diversified oil companies cut back capital in-

vestment in their non-oil divisions.

32

The non-oil divisions were forced to “share

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 975

30

Quoted in A. Chandler and R. S. Tetlow, eds., The Coming of Managerial Capitalism, Richard D. Irwin,

Inc., Homewood, IL: 1985, p. 746.

31

P. Berger and E. Ofek, “Diversification’s Effect on Firm Value,” Journal of Financial Economics 37 (Jan-

uary 1995), pp. 39–65.

32

O. Lamont, “Cash Flow and Investment: Evidence from Internal Capital Markets,” Journal of Finance

52 (March 1997), pp. 83–109.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

the pain,” even though the drop in oil prices did not diminish their investment op-

portunities. The Wall Street Journal reported one example:

33

Chevron Corp. cut its planned 1986 capital and exploratory budget by about 30 per-

cent because of the plunge in oil prices . . . A Chevron spokesman said that spending

cuts would be across the board and that no particular operations will bear the brunt.

About 65 percent of the $3.5 billion budget will be spent on oil and gas explo-

ration and production—about the same proportion as before the budget revision.

Chevron also will cut spending for refining and marketing, oil and natural gas

pipelines, minerals, chemicals, and shipping operations.

Why cut back on capital outlays for minerals, say, or chemicals? Low oil prices are

generally good news, not bad, for chemical manufacturing, because oil distillates

are an important raw material.

By the way, most of the oil companies in Lamont’s sample were large, blue-chip

companies. They could have raised additional capital from investors to maintain

spending in their non-oil divisions. They chose not to. We do not understand why.

All large companies must allocate capital among divisions or lines of business.

Therefore they all have internal capital markets and must worry about mistakes

and misallocations. But this danger probably increases as a company moves from

a focus on one, or a few related industries, to unrelated conglomerate diversifica-

tion. Look again at Table 34.2: How could the top management of ITT keep accu-

rate track of investment opportunities in 38 different industries?

Fifteen Years after Reading this Chapter

You have just seized control of Establishment Industries, the blue-chip conglomer-

ate, after a high-stakes, high-profile takeover battle. You are a financial celebrity,

hounded by business reporters every time you step out of your stretch limo. You’re

contemplating a Ferrari and a trophy spouse. Fundraisers from your college or uni-

versity are suddenly very attentive. But first you’ve got to deliver on promises to

add shareholder value to your renamed New Establishment Corporation.

Fortunately you remember Principles of Corporate Finance. First you identify New

Establishment’s neglected divisions—the poor fits that have not received their

share of capital or top management attention. These you spin off; no more internal

capital market. As independent companies, these divisions can set their own capi-

tal budgets, but to obtain financing, they have to convince outside investors that

their growth opportunities are truly positive-NPV. The managers of these spun-off

companies can buy stock or be given stock options as part of their compensation

packages. Therefore incentives to maximize value are stronger. Investors under-

stand this, so New Establishment’s stock price jumps as soon as the spin-offs are

announced.

Establishment Industries also has some large, mature, cash-cow businesses. You

add still more value by selling some of these divisions to LBO partnerships. You

bargain hard and get a good price, so the stock price jumps again.

The remaining divisions will be the core of New Establishment. You consider

pushing through a leveraged restructuring of these core activities to make sure that

free cash flow is paid out to investors rather than invested in negative-NPV ven-

tures. But you decide instead to implement a performance measurement and com-

976 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

33

Cited in Lamont, op. cit., pp. 89–90.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

pensation system based on residual income.

34

You also make sure managers and

key employees have significant equity stakes. You take over as CEO, and New Es-

tablishment survives and prospers. Your celebrity status fades away, except that

once a year you are listed in Forbes magazine’s annual compilation of the 400

wealthiest executives and investors. It could happen.

Financial Architecture of Traditional U.S. Conglomerates

This fanciful tale sums up the argument for focus and against conglomerate diver-

sification. We must be careful not to push the argument too far, however. GE, an

exceptionally successful company, operates in a wide range of unrelated indus-

tries, including jet engines, equipment leasing, broadcasting, home appliances,

and medical equipment.

But we can confidently identify the challenges set by the financial architecture

of conglomerates.

To add value in the long run, the conglomerate structure sets two tasks for top

management: (1) Make sure divisional management and operating performance

are better than could be achieved if the divisions were independent and (2) oper-

ate an internal capital market that beats the external capital market. In other words,

conglomerate management has to make better capital investment decisions than

could be achieved by independent companies responsible for their own financing.

Task (1) is difficult because divisions’ market values can’t be observed sepa-

rately, and it is difficult to set incentives for divisional managers. Task (2) is diffi-

cult because the conglomerate’s central planners have to fully understand invest-

ment opportunities in many different industries and because internal capital

markets are prone to allocations by bargaining and politics.

Now we turn to a class of conglomerates that does seem to add value. We will

find, however, that they have a different financial architecture.

Temporary Conglomerates

Table 34.3 lists the businesses in which a Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts (KKR) LBO

fund operated in 1998. Looks like a conglomerate, right? But this fund is not a pub-

lic company. It is a private partnership.

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 977

34

That is, on EVA. See Section 12.4.

Books, cards, other publishing (2 companies)

Communications

Consumer services (Kindercare Learning Centers)

Fiber optics (coupling and connections)

General food products

Golf and healthcare products (1 company)

Hospital and institutional management

Insurance (in Canada)

Other consumer products (1 company)

Printing and binding

Transportation equipment and parts

TABLE 34.3

KKR formed an LBO partnership in 1993. By 1998 this fund

held companies in the following industries. The partnership

was a (temporary) conglomerate.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

This KKR fund is a private investment partnership and a temporary conglomerate. It

buys up companies, generally in unrelated industries, but it does not buy and hold. It

tries to buy, fix, and sell. It buys to restructure, to dispose of incidental assets, and to

improve operations and management. If the program of improvement is a success, it

sells out, either by taking the company public again or by selling it to another firm.

KKR is famous for LBOs. But its financial structure is shared by venture capital

partnerships formed to invest in startup companies and by partnerships formed to

buy up private companies without LBO financing. These are all private equity part-

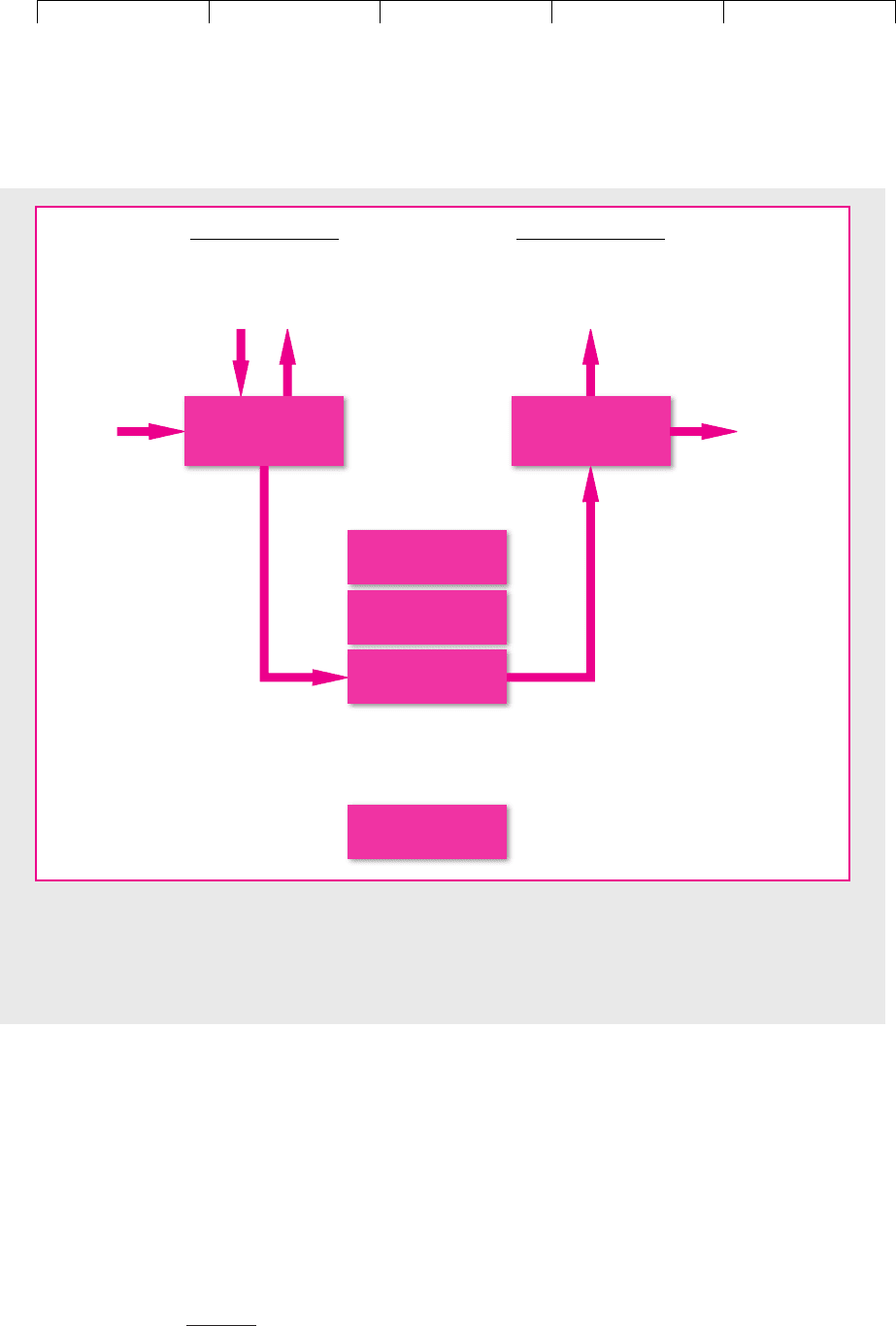

nerships. Figure 34.2 shows how such a partnership is organized. The general part-

ners organize and manage the venture. The limited partners

35

put up most of the

978 PART X

Mergers, Corporate Control, and Governance

35

Limited partners enjoy limited liability. See Section 14.2.

Partnership

General partners

put up 1% of

capital

Management

fees

Limited

partners

put in

99% of

capital

Investment

in diversified

portfolio

of companies

Sale or IPO

of companies

Limited

partners get

investment

back, then

80% of

profits

Investment Phase

Company 1

Company 2

Company 3

Company

N

•

•

•

Partnership

General partners

get carried interest

in 20% of profits

Payout Phase

FIGURE 34.2

Organization of a typical private equity partnership. The limited partners, having put up almost all of the money,

get first crack at the proceeds from sale or IPO of the portfolio companies. Once their investment is returned, they

get 80 percent of any profits. The general partners, who organize and manage the partnership, get a 20 percent

carried interest in profits.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

X. Mergers, Corporate

Control, and Governance

34. Control Governance,

and Financial Architecture

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

money. Limited partners are generally institutional investors, such as pension

funds, endowments, and insurance companies. Wealthy individuals or families

may also participate.

Once the partnership is formed, the general partners seek out companies to in-

vest in. Venture capital partnerships look for high-tech startups, LBO partnerships

for mature businesses with ample free cash flow and a need for new or reinvigo-

rated management. Some partnerships specialize in particular industries, for ex-

ample biotechnology or real estate. But most end up with a portfolio of companies

in different industries.

The partnership agreement has a limited term, 10 years or less. The portfolio

companies must be sold and the proceeds must be distributed. The general part-

ners cannot reinvest the limited partners’ money. Of course, once a fund is proved

successful, the general partners can usually go back to the limited partners, or to

other institutional investors, and form another one.

The general partners get a management fee, typically 1 or 2 percent of capital

committed, plus a carried interest, usually 20 percent of the fund’s profits. In other

words the limited partners get paid off first, but then get only 80 percent of any fur-

ther returns. (The general partners have a call option on 20 percent of the partner-

ship’s value, with an exercise price equal to the limited partners’ investment.)

Table 34.4 summarizes a comparison by Baker and Montgomery of the financial

structures of an LBO fund and a typical public conglomerate. Both are diversified,

but the fund’s limited partners do not have to worry that free cash flow will be

plowed back into unprofitable investments. The fund has no internal capital mar-

ket. Monitoring and compensation of management also differ. In the LBO fund,

each company is run as a separate business. The managers report directly to the

owners, the fund’s partners. Each company’s managers own shares or stock op-

tions in that company, not in the fund. Their compensation depends on their com-

pany’s market value in a sale or IPO.

In a public conglomerate, these businesses would be divisions, not freestanding

companies. Ownership of the conglomerate would be dispersed, not concentrated.

The divisions would not be valued by investors in the stock market, but by the con-

glomerate’s corporate staff, the very people who run the internal capital market.

CHAPTER 34

Control, Governance, and Financial Architecture 979

LBO Partnerships Public Conglomerates

Widely diversified, Widely diversified,

investment in unrelated investment in unrelated

industries industries

Limited-life partnership Public corporations designed

forces sale of portfolio to operate divisions for the long run

companies.

No financial links or transfers Internal capital market

between portfolio

companies

General partners “do the Hierarchy of corporate staff evaluates

deal,” then monitor; lenders divisions’ plans and performance.

also monitor.

Managers’ compensation Divisional managers’ compensation

depends on exit value of depends mostly on earnings—“smaller

company. upside, softer downside.”

TABLE 34.4

LBO funds vs. public

conglomerates. Both diversify,

investing in a portfolio of

unrelated businesses, but their

financial structures are

otherwise fundamentally

different.

Source: Adapted from G. Baker and

C. Montgomery, “Conglomerates

and LBO Associations: A

Comparison of Organizational

Forms,” working paper, Harvard

Business School, Cambridge, MA,

July 1996.