Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

bonds sell at different prices, you must dig deeper and look at the separate interest

rates for one-year cash flows, for two-year cash flows, and so on. In other words, you

must look at the spot rates of interest.

To find the spot interest rate, you need the price of a bond that simply makes one

future payment. Fortunately, such bonds do exist. They are known as stripped bonds

or strips. Strips originated in 1982 when several investment bankers came up with

a novel idea. They bought U.S. Treasury bonds and reissued their own separate

mini-bonds, each of which made only one payment. The idea proved to be popu-

lar with investors, who welcomed the opportunity to buy the mini-bonds rather

than the complete package. If you’ve got a smart idea, you can be sure that others

will soon clamber onto your bandwagon. It was therefore not long before the Trea-

sury issued its own mini-bonds.

13

The prices of these bonds are shown each day in

the daily press. For example, in the summer of 2001, a strip maturing in May 2021

cost $316.55 and 20 years later will give the investors a single payment of $1,000.

Thus the 20-year spot rate was , or 5.92 percent.

14

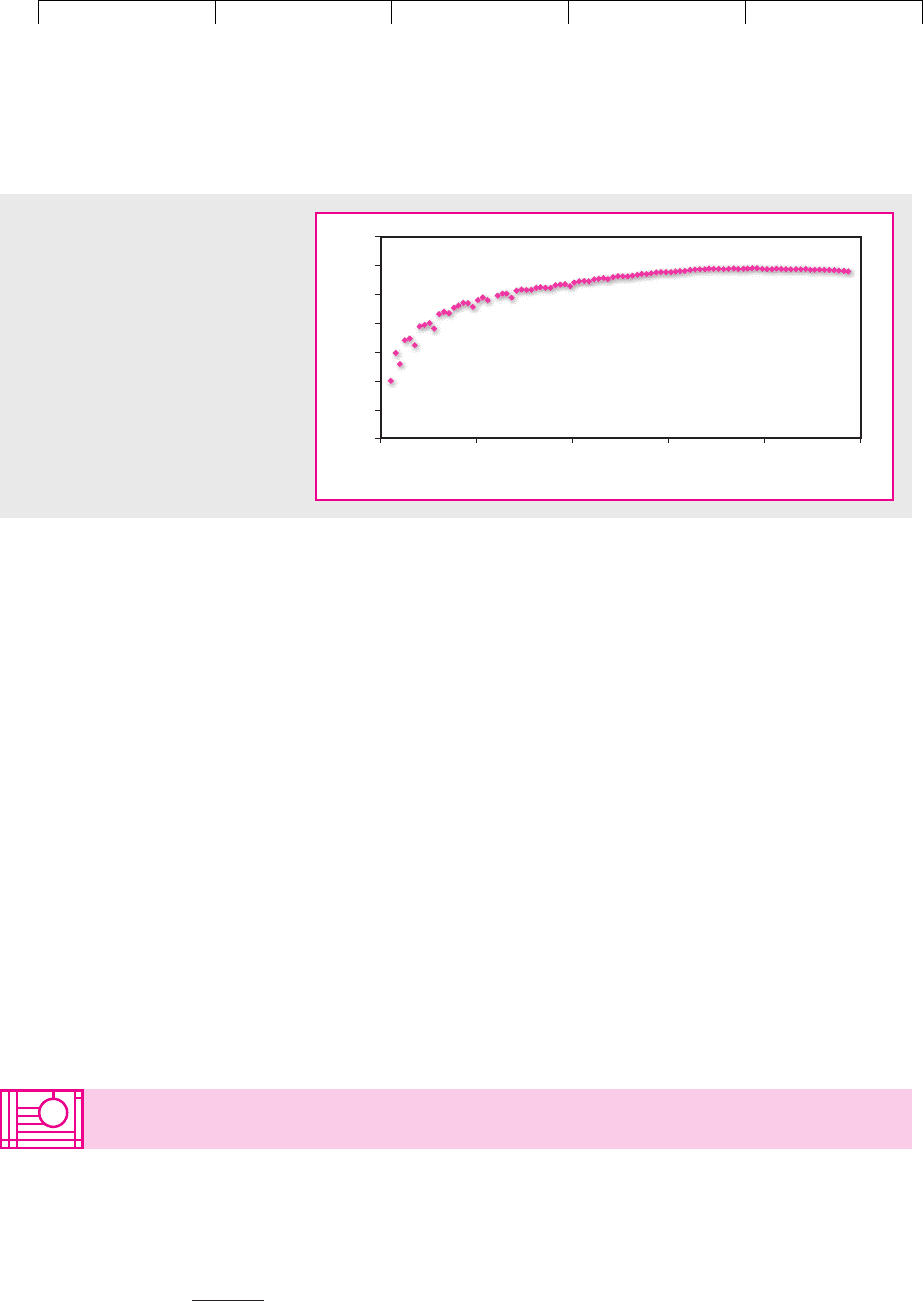

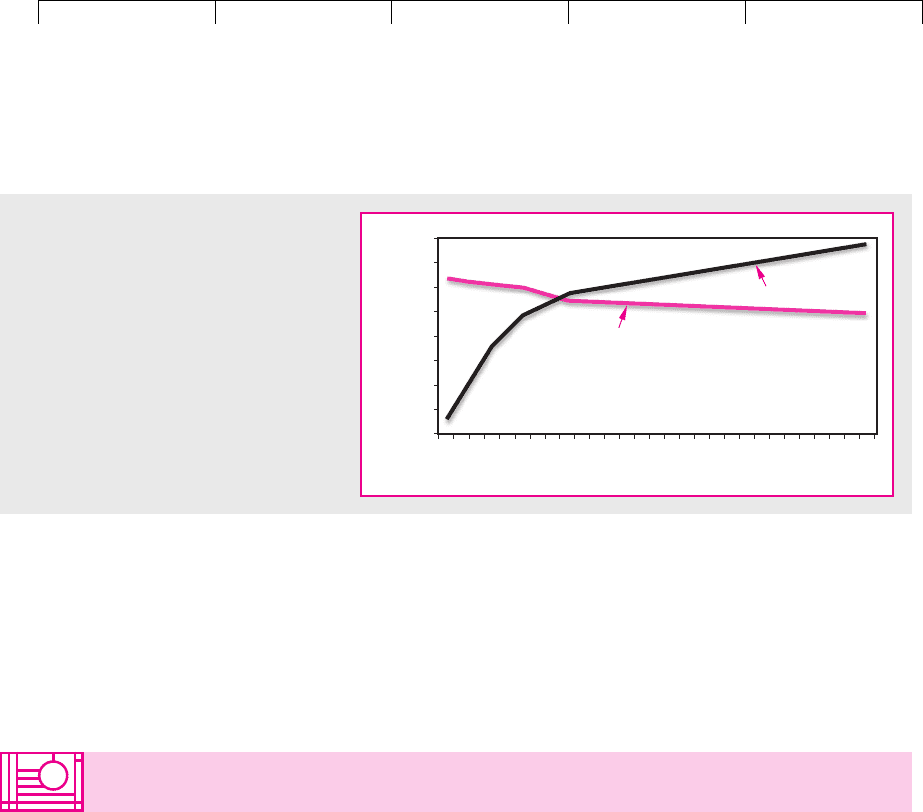

In Figure 24.3 we have used the prices of strips with different maturities to plot

the term structure of spot rates from 1 to 24 years. You can see that investors re-

quired an interest rate of 3.4 percent from a bond that made a payment only at the

end of one year and a rate of 5.8 percent from a bond that paid off only in year 2025.

11000/316.552

1/20

⫺ 1 ⫽ .0592

674 PART VII

Debt Financing

13

The Treasury continued to auction coupon bonds in the normal way, but investors could exchange

them at the Federal Reserve Bank for stripped bonds.

14

This is an annually compounded rate. The yields quoted by investment dealers are semiannually

compounded rates.

0

2001

2006 2011

Year

2016 2021 2026

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Spot rate, percent

FIGURE 24.3

Spot rates on U.S. Treasury strips,

June 2001.

24.3 HOW INTEREST RATE CHANGES AFFECT BOND

PRICES

Duration and Bond Volatility

In Chapter 7 we reviewed the historical performance of different security classes.

We showed that since 1926 long-term government bonds have provided a higher

average return than short-term bills, but have also been more variable. The stan-

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

dard deviation of annual returns on a portfolio of long-term bonds was 9.4 percent

compared with a standard deviation of 3.2 percent for bills.

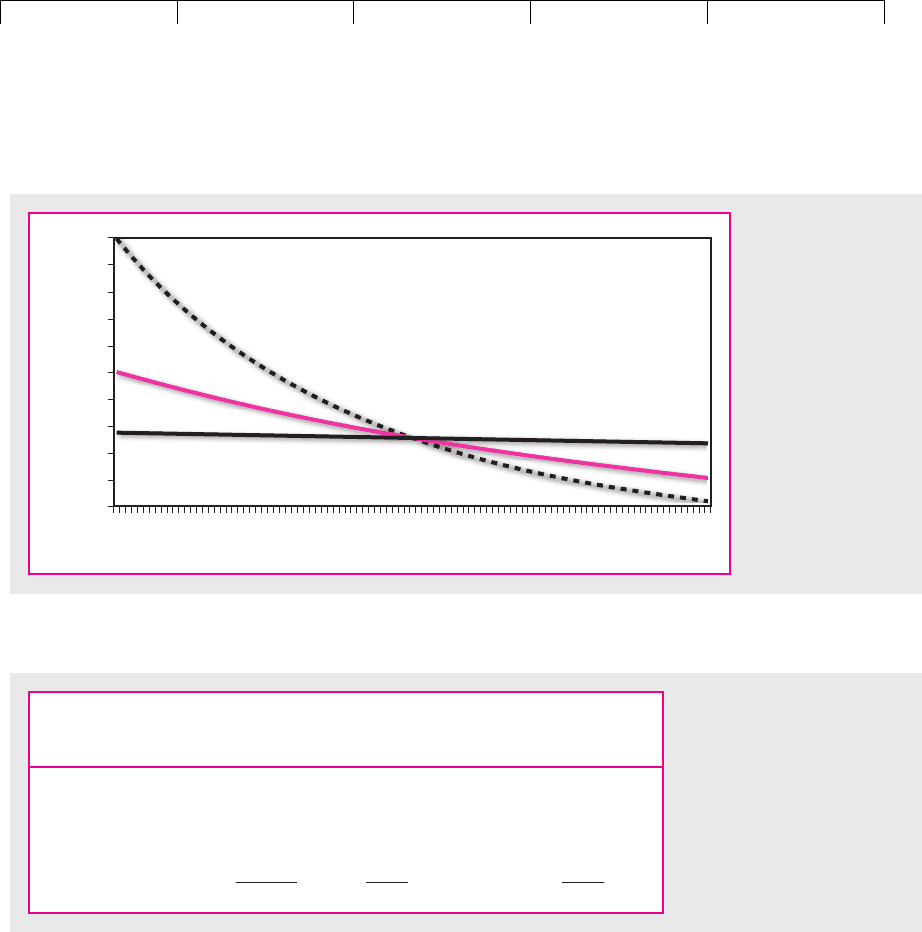

Figure 24.4 illustrates why long-term bonds are more variable. Each line shows

how the price of a 5-percent bond changes with the level of interest rates. You can

see that the price of a longer-term bond is more sensitive to interest rate fluctua-

tions than that of a shorter bond.

But what do we mean by long-term and short-term bonds? It is obvious in the

case of strips that make payments in only one year. However, a coupon bond that

matures in year 10 makes payments in each of years 1 through 10. Therefore, it is

somewhat misleading to describe the bond as a 10-year bond; the average time to

each cash flow is less than 10 years.

Consider the Treasury 6 7/8s of 2006. In mid-2001 these bonds had a present

value of 108.57 percent of face value and yielded 4.9 percent. The third and fourth

columns in Table 24.2 show where this present value comes from. Notice that the

cash flow in year 5 accounts for only 77.5 percent of the bond’s value. The remain-

ing 22.5 percent of the value comes from the earlier cash flows.

CHAPTER 24

Valuing Debt 675

50

70

90

110

130

150

170

190

210

230

250

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Interest rate, percent

Bond price, percent

30-year 5 percent bond

10-year

5 percent bond

1-year 5 percent bond

FIGURE 24.4

How bond prices

change as interest

rates change. Note

that longer-term

bonds are more

sensitive to interest

rate changes.

Proportion of

Total Value Proportion of

Year C

t

PV(C

t

) at 4.9% [PV(C

t

)/V] Total Value ⴛ Time

1 68.75 65.54 0.060 0.060

2 68.75 62.48 0.058 0.115

3 68.75 59.56 0.055 0.165

4 68.75 56.78 0.052 0.209

5 1068.75 841.39 0.775 3.875

V ⫽ 1085.74 1.000 Duration ⫽ 4.424 years

TABLE 24.2

The first four columns show

that the cash flow in year 5

accounts for only 77.5 percent

of the present value of the

6 7/8s of 2006. The final

column shows how to calculate

a weighted average of the time

to each cash flow. This average

is the bond’s duration.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Bond analysts often use the term duration to describe the average time to each

payment. If we call the total value of the bond V, then duration is calculated as

follows:

15

For the 6 7/8s of 2006,

The Treasury 4 5/8s of 2006 have the same maturity as the 6 7/8s, but the first four

years’ coupon payments account for a smaller fraction of the bond’s value. In this

sense the 4 5/8s are longer bonds than the 6 7/8s. The duration of the 4 5/8s is

4.574 years.

Consider now what happens to the prices of our two bonds as interest rates

change:

Duration ⫽ 11 ⫻ .0602⫹ 12 ⫻ .0582⫹ 13 ⫻ .0552⫹

…

⫽ 4.424 years

Duration ⫽

31 ⫻ PV1C

1

24

V

⫹

32 ⫻ PV1C

2

24

V

⫹

33 ⫻ PV1C

3

24

V

⫹

…

676 PART VII Debt Financing

15

This measure is also known as Macaulay duration after its inventor. See F. Macaulay, Some Theoretical

Problems Suggested by the Movements of Interest Rates, Bond Yields, and Stock Prices in the United States since

1856, National Bureau of Economic Research, New York, 1938.

16

For this reason volatility is also called modified duration.

6 7/8s of 2006 4 5/8s of 2006

New Price Change New Price Change

Yield falls .5% 1108.96 ⫹2.14% 1009.91 ⫹2.21%

Yield rises .5% 1063.16 ⫺2.08% 966.81 ⫺2.15%

Difference 4.22% 4.36%

Thus, a 1 percentage-point variation in yield causes the price of the 6 7/8s to change

by 4.22 percent. We can say that the 6 7/8s have a volatility of 4.22 percent, while

the 4 5/8s have a volatility of 4.36 percent.

Notice that the 4 5/8 percent bonds have the greater volatility and that they

also have the longer duration. In fact, a bond’s volatility is directly related to its

duration:

16

In the case of the 6 7/8s,

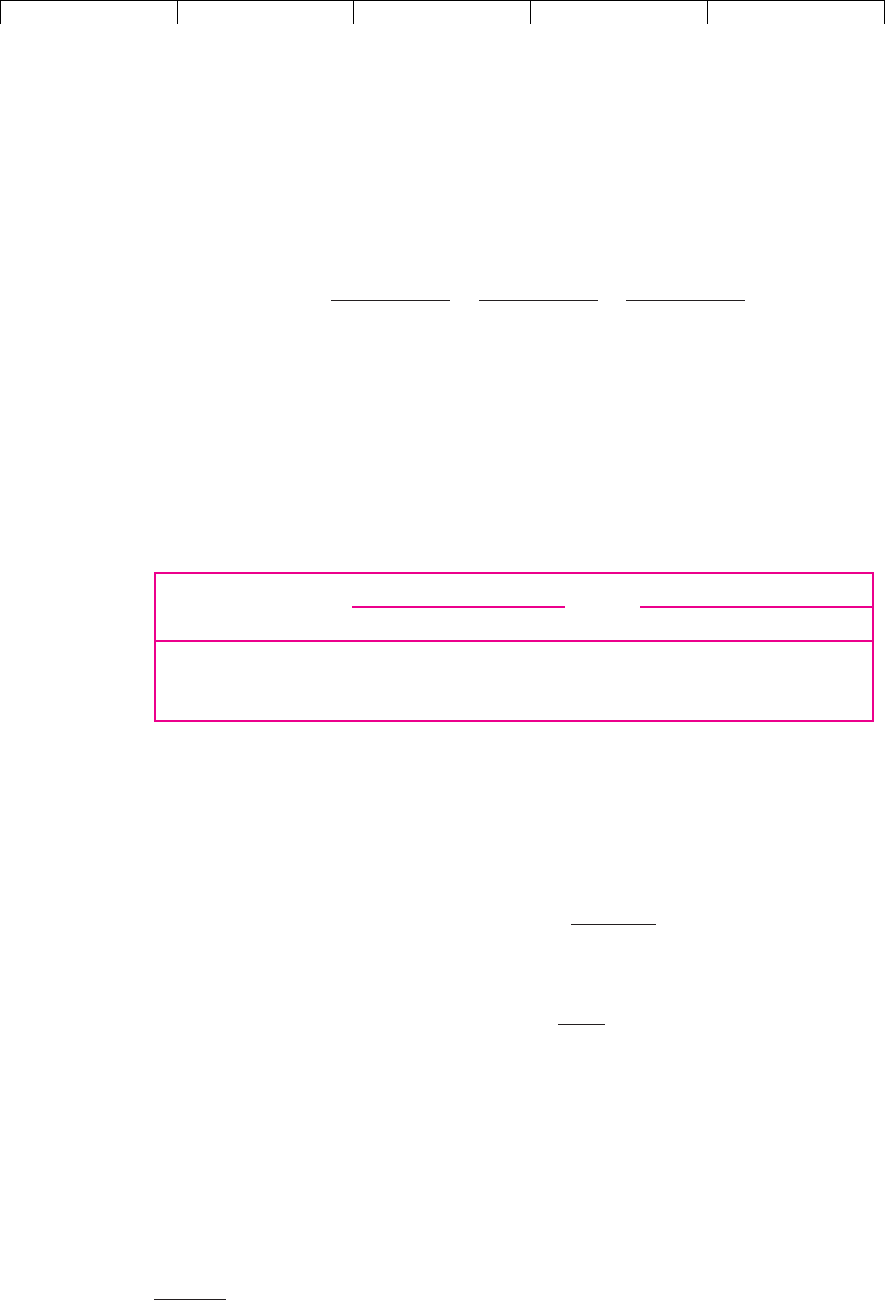

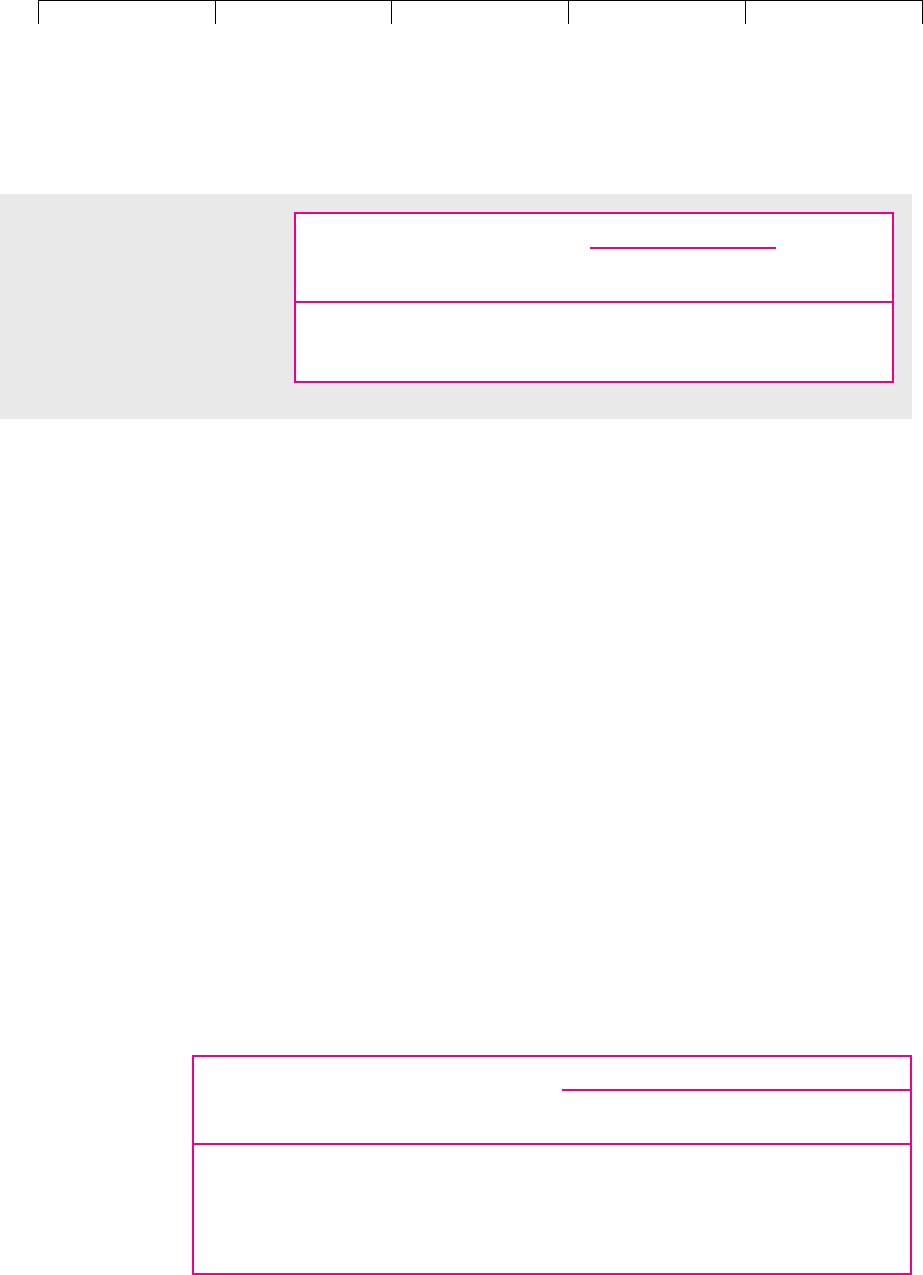

In Figure 24.4 we showed how bond prices vary with the level of interest rates. Each

bond’s volatility is simply the slope of the line relating the bond price to the interest

rate. You can see this more clearly in Figure 24.5, where the convex curve shows the

price of the 5 percent 30-year bond for different interest rates. The bond’s volatility is

measured by the slope of a tangent to this curve. For example, the dotted line in the

figure shows that, if the interest rate is 5 percent, the curve has a slope of 15.4. At this

point the change in bond price is 15.4 times a change in the interest rate. Notice that

the bond’s volatility changes as the interest rate changes. Volatility is higher at lower

interest rates (the curve is steeper), and it is lower at higher rates (the curve is flatter).

Volatility 1percent2⫽

4.424

1.049

⫽ 4.22

Volatility 1percent2⫽

duration

1 ⫹ yield

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Managing Interest Rate Risk

Volatility is a useful, summary measure of the likely effect of a change in interest

rates on the value of a bond. The longer a bond’s duration, the greater is its volatil-

ity. In Chapter 27 we will make use of this relationship between duration and

volatility to describe how firms can protect themselves against interest rate

changes. Here is an example that should give you a flavor of things to come.

Suppose your firm has promised to make pension payments to retired employ-

ees. The discounted value of these pension payments is $1 million; therefore, the

firm puts aside $1 million in the pension fund and invests the money in govern-

ment bonds. So the firm has a liability of $1 million and (through the pension fund)

an offsetting asset of $1 million. But, as interest rates fluctuate, the value of the pen-

sion liability will change and so will the value of the bonds in the pension fund.

How can the firm ensure that the value of the bonds in the fund is always sufficient

to meet the liabilities? Answer: By making sure that the duration of the bonds is al-

ways the same as the duration of the pension liability.

A Cautionary Note

Bond volatility measures the effect on bond prices of a shift in interest rates. For ex-

ample, we calculated that the 6 7/8s had a volatility of 4.22. This means a 1 percentage-

point change in interest rates leads to a 4.22 percent change in bond price:

This relationship is sometimes called a one-factor model of bond returns; it tells us

how each bond’s price changes in response to one factor—a change in the overall

level of interest rates. One-factor models have proved very useful in helping firms

to understand how they are affected by interest-rate changes and how they can

protect themselves against these risks.

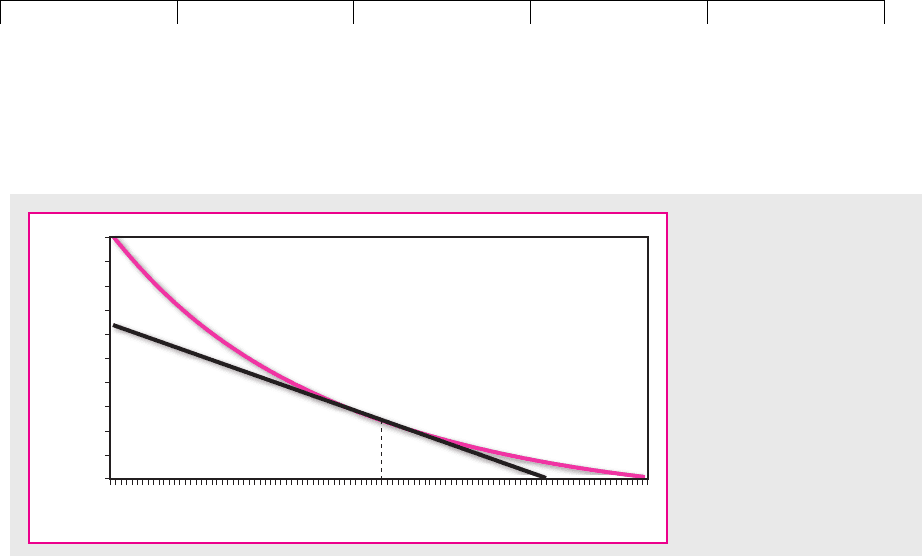

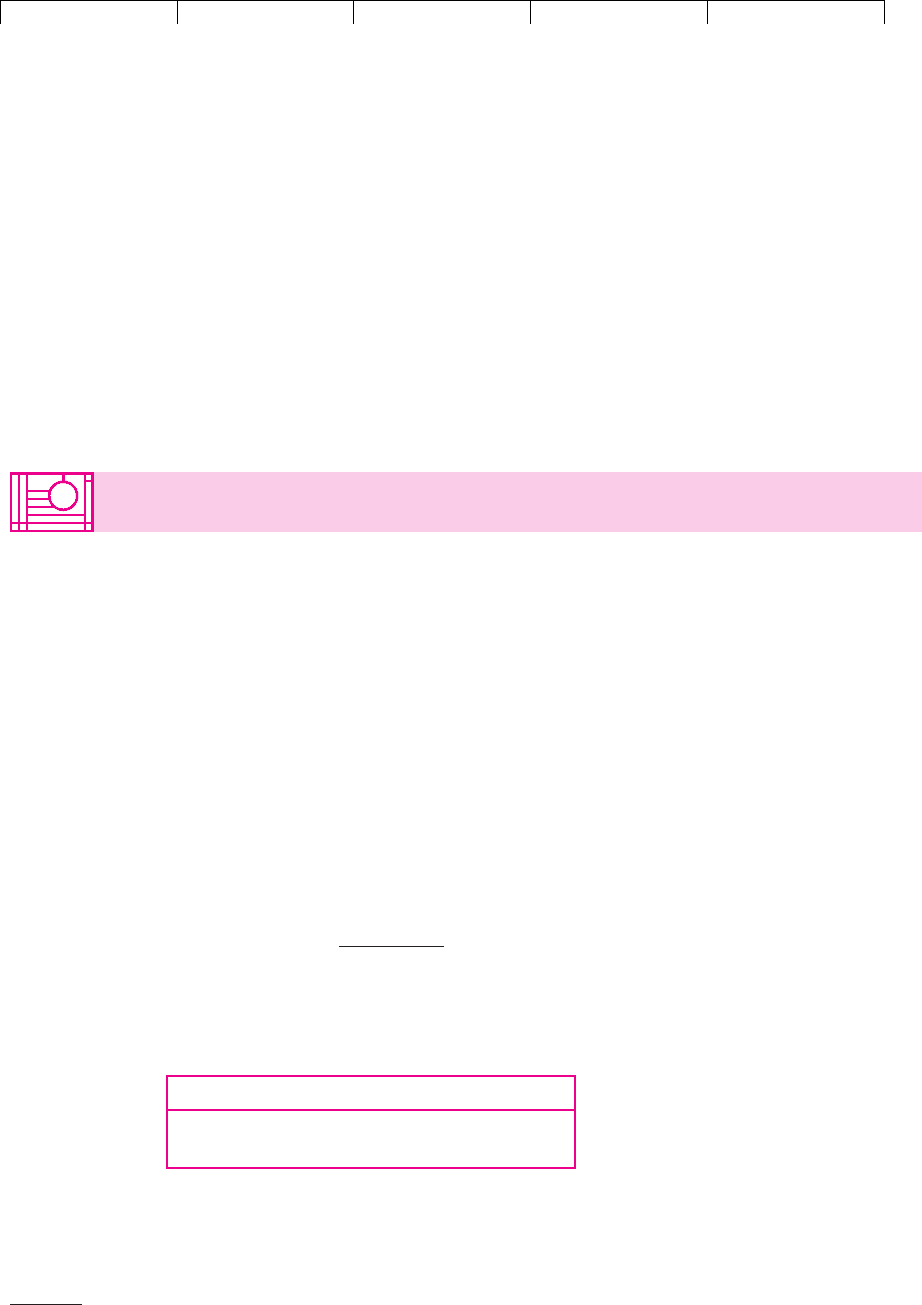

If the yields on all Treasury bonds moved in precise lockstep, then changes in

the price of each bond would be exactly proportional to the bond’s duration. For

example, the price of a long-term bond with a duration of 20 years would always

rise or fall twice as much as the price of a medium-term bond with a duration of 10

years. However, Figure 24.6 illustrates that short- and long-term interest rates do

Change in bond price ⫽ 4.22 ⫻ change in interest rates

CHAPTER 24

Valuing Debt 677

50

70

90

110

130

150

170

190

210

230

250

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Interest rate, percent

Bond price, percent

FIGURE 24.5

Volatility is the slope of the

curve relating the bond price

to the interest rate. For

example, a 5 percent 30-year

bond has a volatility of 15.4

when the interest rate is 5

percent. At this point the

change in price is 15.4 times

the change in the interest

rate. Its volatility is higher at

lower interest rates (the curve

is steeper) and lower at

higher rates (the curve is

flatter).

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

not always move in perfect unison. Between 1992 and 2000 short-term interest rates

nearly doubled while long-term rates declined. As a result, the term structure,

which initially sloped steeply upward, shifted to a downward slope. Because

short- and long-term yields do not move in parallel, one-factor models cannot be

the whole story, and managers need to worry not just about the risks of an overall

change in interest rates but also about shifts in the term structure.

678 PART VII

Debt Financing

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

6.5

7

7.5

2

3 5 7 10 30

Bond maturity, years

Yield, percent

April 2000

September 1992

FIGURE 24.6

Short-term and long-term interest rates do

not always move in parallel. Between

September 1992 and April 2000 short-term

rates rose sharply while long-term rates

declined.

24.4 EXPLAINING THE TERM STRUCTURE

The term structure that we showed in Figure 24.3 was upward-sloping. In other

words, long rates of interest are higher than short rates. This is the more common

pattern but sometimes it is the other way around, with short rates higher than long

rates. Why do we get these shifts in term structure?

Let us look at a simple example. Figure 24.3 showed that in the summer of 2001

the one-year spot rate was about 3.5 percent. The two-year spot rate was

higher at 4 percent. Suppose that in 2001 you invest in a one-year U.S. Treasury

strip. You would earn the one-year spot rate of interest and by the end of the year

each dollar that you invested would have grown to . If instead

you were prepared to invest for two years, you would earn the two-year spot rate

of and by the end of the two years each dollar would have grown to

. By keeping your money invested for a further year,

your savings grow from $1.0350 to $1.0816, an increase of 4.5 percent. This extra 4.5

percent that you earn by keeping your money invested for two years rather than

one is termed the forward interest rate or .

Notice how we calculated the forward rate. When you invest for one year, each

dollar grows to . When you invest for two years, each dollar grows to

. Therefore, the extra return that you earn for that second year is

. In our example,

If you twist this equation around, you obtain an expression for the two-year spot

rate, , in terms of the one-year spot rate, , and the forward rate, :

11 ⫹ r

2

2

2

⫽ 11 ⫹ r

1

2⫻ 11 ⫹ f

2

2

f

2

r

1

r

2

f

2

⫽ 11 ⫹ r

2

2

2

/11 ⫹ r

1

2⫺ 1 ⫽ 11.042

2

/11.0352⫺ 1 ⫽ .045, or 4.5%

f

2

⫽ 11 ⫹ r

2

2

2

/11 ⫹ r

1

2⫺ 1

$11 ⫹ r

2

2

2

$11 ⫹ r

1

2

f

2

$11 ⫹ r

2

2

2

⫽ $1.04

2

⫽ $1.0816

r

2

$11 ⫹ r

1

2⫽ $1.035

1r

2

21r

1

2

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

In other words, you can think of the two-year investment as earning the one-year spot

rate for the first year and the extra return, or forward rate, for the second year.

The Expectations Theory

Would you have been happy in the summer of 2001 to earn an extra 4.5 percent

for investing for two years rather than one? The answer depends on how you ex-

pected interest rates to change over the coming year. Suppose, for example, that

you were confident that interest rates would rise sharply, so that at the end of the

year the one-year rate would be 5 percent. In that case rather than investing in a

two-year bond and earning the extra 4.5 percent for the second year, you would

do better to invest in a one-year bond and, when that matured, to reinvest the

money for a further year at 5 percent. If other investors shared your view, no one

would be prepared to hold the two-year bond and its price would fall. It would

stop falling only when the extra return from holding the two-year bond equalled

the expected future one-year rate. Let us call this expected rate —that is, the

spot rate of interest at year 1 on a loan maturing at the end of year 2.

17

Figure 24.7

shows that at that point investors would earn the same expected return from in-

vesting in a two-year loan as from investing in two successive one-year loans.

This is known as the expectations theory of term structure.

18

It states that in equi-

librium the forward interest rate, , must equal the expected one-year spot rate, .

The expectations theory implies that the only reason for an upward-sloping term

structure, such as existed in the summer of 2001, is that investors expect short-term

interest rates to rise; the only reason for a declining term structure is that investors ex-

pect short-term rates to fall.

19

The expectations theory also implies that investing in

a succession of short-term bonds gives exactly the same expected return as investing

in long-term bonds.

If short-term interest rates are significantly lower than long-term rates, it is of-

ten tempting to borrow short-term rather than long-term. The expectations theory

1

r

2

f

2

1

r

2

CHAPTER 24 Valuing Debt 679

17

Be careful to distinguish from , the spot interest rate on a two-year bond held from time 0 to time

2. The quantity is a one-year spot rate established at time 1.

18

The expectations theory is usually attributed to Lutz and Lutz. See F. A. Lutz and V. C. Lutz, The The-

ory of Investment in the Firm, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1951.

19

This follows from our example. If the two-year spot rate, , exceeds the one-year rate, , then the for-

ward rate, , also exceeds . If the forward rate equals the expected spot rate, then must also ex-

ceed . The converse is likewise true.r

1

1

r

21

r

2

r

1

f

2

r

1

r

2

1

r

2

r

21

r

2

(

a

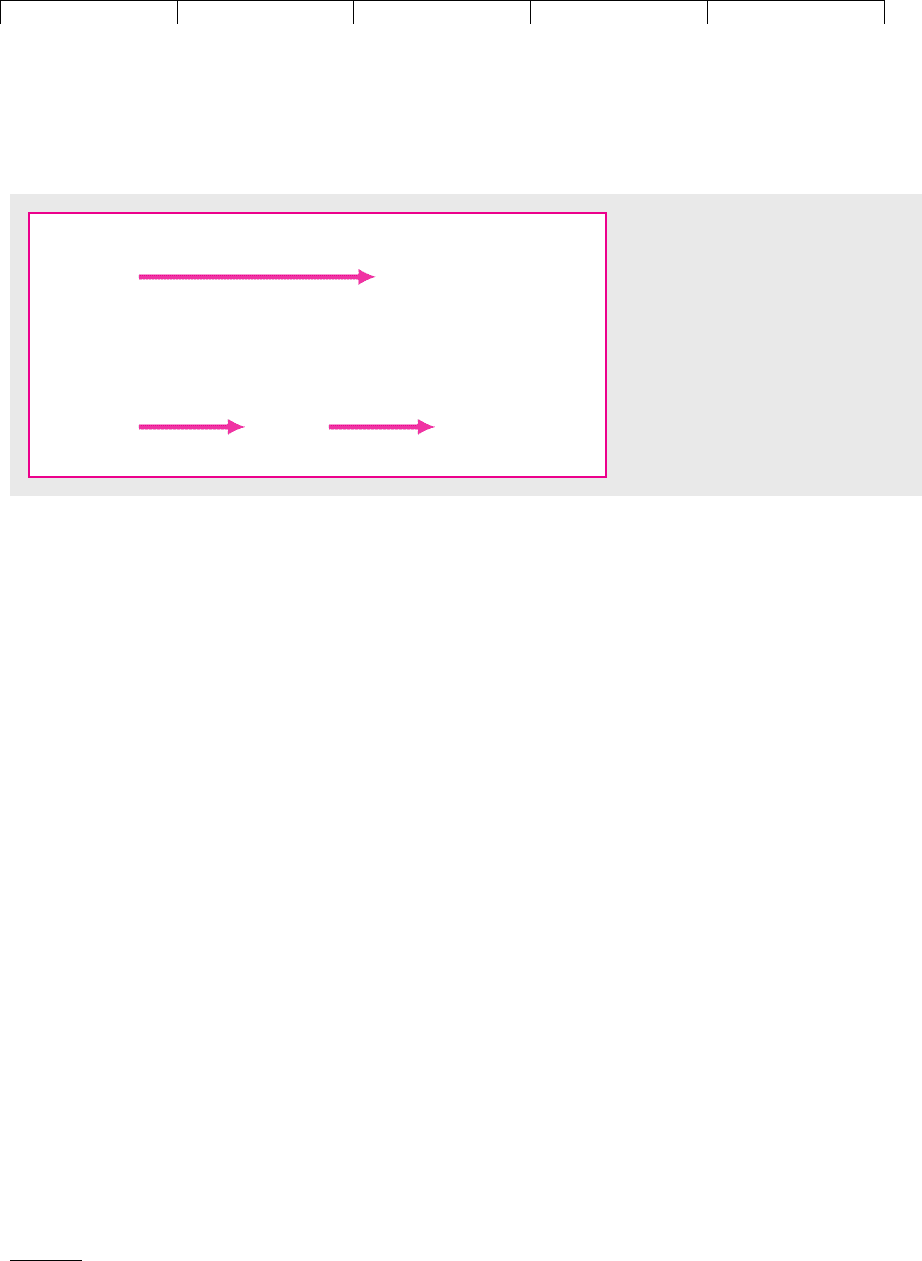

) The future value of $1 invested in a two-year loan

Period 0 Period 2

(1 +

r

2

)

2

= (1 +

r

1

) ⫻ (1 +

f

2

)

(

b

) The future value of $1 invested in two successive one-year loans

Period 0 Period 1

(1 +

r

1

) ⫻ (1 +

1

r

2

)

Period 2

FIGURE 24.7

An investor can invest either in a

two-year loan [a] or in two successive

one-year loans [b]. The expectations

theory says that in equilibrium the

expected payoffs from these two

strategies must be equal. In other

words, the forward rate, , must

equal the expected spot rate, .

1

r

2

f

2

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

implies that such naïve strategies won’t work. If short rates are lower than long

rates, then investors must be expecting interest rates to rise. When the term struc-

ture is upward-sloping, you are likely to make money by borrowing short only if

investors are overestimating future increases in interest rates.

Even on a casual glance the expectations theory does not seem to be the com-

plete explanation of term structure. For example, if we look back over the period

1926–2000, we find that the return on long-term U.S. Treasury bonds was on aver-

age 1.9 percent higher than the return on short-term Treasury bills. Perhaps short-

term interest rates did not go up as much as investors expected, but it seems more

likely that investors wanted a higher expected return for holding long bonds and

that on the average they got it. If so, the expectations theory is wrong.

The expectations theory has few strict adherents, but most economists believe

that expectations about future interest rates have an important effect on term struc-

ture. For example, the expectations theory implies that if the forward rate of inter-

est is 1 percent above the spot rate of interest, then your best estimate is that the

spot rate of interest will rise by 1 percent. In a study of the U.S. Treasury bill mar-

ket between 1959 and 1982, Eugene Fama found that a forward premium does on

average precede a rise in the spot rate but the rise is less than the expectations the-

ory would predict.

20

The Liquidity-Preference Theory

What does the expectations theory leave out? The most obvious answer is “risk.”

If you are confident about the future level of interest rates, you will simply choose

the strategy that offers the highest return. But, if you are not sure of your forecast,

you may well opt for the less risky strategy even if it offers a lower expected return.

Remember that the prices of long-duration bonds are more volatile than those

of short-term bonds. For some investors this extra volatility may not be a concern.

For example, pension funds and life insurance companies with long-term liabili-

ties may prefer to lock in future returns by investing in long-term bonds. However,

the volatility of long-term bonds does create extra risk for investors who do not

have such long-term fixed obligations.

Here we have the basis for the liquidity-preference theory of the term struc-

ture.

21

If investors incur extra risk from holding long-term bonds, they will de-

mand the compensation of a higher expected return. In this case the forward rate

must be higher than the expected spot rate. This difference between the forward

rate and the expected spot rate is usually called the liquidity premium. If the

liquidity-preference theory is right, the term structure should be upward-sloping

more often than not. Of course, if future spot rates are expected to fall, the term

structure could be downward-sloping and still reward investors for lending long.

But the liquidity-preference theory would predict a less dramatic downward

slope than the expectations theory.

680 PART VII

Debt Financing

20

See E. F. Fama, “The Information in the Term Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 13 (December

1984), pp. 509–528. Evidence from the Treasury bond market that the forward premium has some power

to predict changes in spot rates is provided in J. Y. Campbell, A. W. Lo, and A. C. MacKinlay, The Econo-

metrics of Financial Markets, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1997, pp. 421–422.

21

The liquidity-preference hypothesis is usually attributed to Hicks. See J. R. Hicks, Value and Capital:

An Inquiry into Some Fundamental Principles of Economic Theory, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Ox-

ford, 1946. For a theoretical development, see R. Roll, The Behavior of Interest Rates: An Application of the

Efficient-Market Model to U.S. Treasury Bills, Basic Books, Inc., New York, 1970.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Introducing Inflation

The money cash flows on a U.S. Treasury bond are certain, but the real cash flows

are not. In other words, Treasury bonds are still subject to inflation risk. Let us look

therefore at how uncertainty about inflation affects the risk of bonds with different

maturities.

22

Suppose that Irving Fisher is right and short rates of interest always incorporate

fully the market’s latest views about inflation. Suppose also that the market learns

more as time passes about the likely inflation rate in a particular year. Perhaps to-

day investors have only a very hazy idea about inflation in year 2, but in a year’s

time they expect to be able to make a much better prediction. Since investors ex-

pect to learn a good deal about the inflation rate in year 2 from experience in year

1, next year they will be in a much better position to judge the appropriate interest

rate in year 2.

You are saving for your retirement. Which of the following strategies is the more

risky? Invest in a succession of one-year Treasury bonds or invest in a 20-year bond?

If you buy the 20-year bond, you know what money you will have at the end of

20 years, but you will be making a long-term bet on inflation. Inflation may seem

benign now, but who knows what it will be in 10 or 20 years? This uncertainty

about inflation makes it more risky for you to fix today the rates at which you will

lend in the distant future.

You can reduce this uncertainty by investing in successive short-term bonds.

You do not know the interest rate at which you will be able to reinvest your money

at the end of each year, but at least you know that it will incorporate the latest in-

formation about inflation in the coming year. So, if the prospects for inflation de-

teriorate, it is likely that you will be able to reinvest your money at a higher inter-

est rate.

Inflation uncertainty may help to explain why long-term bonds provide a liquid-

ity premium. If inflation creates additional risks for long-term lenders, borrowers

must offer some incentive if they want investors to lend long. Therefore, the forward

rate of interest must be greater than the expected spot rate by an amount that

compensates investors for the extra risk of inflation.

Relationships between Bond Returns

These term structure theories tell us how bond prices may be determined at a point

in time. More recently, financial economists have proposed some important theo-

ries of how price movements are related. These theories take advantage of the fact

that the returns on bonds with different maturities tend to move together. For ex-

ample, if short-term interest rates are high, it is a good bet that long-term rates will

also be high. If short-term rates fall, long-term rates usually keep them company.

Such linkages between interest rate movements can tell us something about rela-

tionships between bond prices.

The models that bond traders use to exploit these relationships can be quite

complex and we can’t get deeply into the subject here. However, the following ex-

ample will give you a flavor of how the models work.

Suppose that you can invest in three possible government loans: a three-

month Treasury bill, a medium-term bond, and a long-term bond. The return on

E1

1

r

2

2

f

2

CHAPTER 24 Valuing Debt 681

22

See R. A. Brealey and S. M. Schaefer, “Term Structure and Uncertain Inflation,” Journal of Finance 32

(May 1977), pp. 277–290.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

the Treasury bill over the next three months is certain; we will assume it yields a

2 percent quarterly rate. The return on each of the other bonds depends on what

happens to interest rates. Suppose that you foresee only two possible outcomes—

a sharp rise in interest rates or a sharp fall. Table 24.3 summarizes how the prices

of the three investments would be affected. Notice that the long-term bond has a

longer duration and therefore a wider range of possible outcomes.

Here’s the puzzle. You know the price of the Treasury bill and the long-term

bond. But can you get rid of the two question marks in Table 24.3 and figure out

what the medium-term bond should sell for?

Suppose that you start with $100. You invest half of this money in the Treasury

bill and half in the long-term bond. In this case the change in the value of your

portfolio will be if interest rates rise and

if interest rates fall. Thus, regardless of whether in-

terest rates rise or fall, your portfolio will provide exactly the same payoffs as an

investment in the medium-term bond. Since the two investments provide identi-

cal payoffs, they must sell for the same price or there will be a money machine.

So, the value of the medium-term bond must be halfway between the value of a

three-month bill and that of the long-term bond, that is, .

Knowing this, you can calculate what the yield to maturity on the medium-term

bond has to be. You can also calculate its value next year, either

or .

Everything now checks; regardless of whether interest rates rise or fall, the

medium-term bond will provide the same payoff as the package of Treasury bill

and long-term bond and therefore it must cost the same:

101.5 ⫹ 10 ⫽ 111.5

101.5 ⫺ 6.5 ⫽ 95

198 ⫹ 1052/2 ⫽ 101.5

1.5 ⫻ 22⫹ 1.5 ⫻ 182⫽⫹$10

1.5 ⫻ 22⫹ 3.5 ⫻ 1⫺1524 ⫽⫺$6.5

682 PART VII

Debt Financing

Change in Value

Beginning If Interest If Interest Ending

Price Rates Rise Rates Fall Value

Treasury bill 98 ⫹2 ⫹2 100

Medium-term bond ? ⫺6.5 ⫹10 ?

Long-term bond 105 ⫺15 ⫹18 90 or 123

TABLE 24.3

Illustrative payoffs from three

government securities. Note the

wider range of outcomes from the

longer-duration loans. We don’t

know what the medium-term bond

sells for; we need to figure it out

from how its value changes when

interest rates rise or fall.

Ending Value

Initial If Interest If Interest

Outlay Rates Rise Rates Fall

Equal holdings (.5 ⫻ 98) ⫹ (.5 ⫻ (.5 ⫻ 100) ⫹ (.5 ⫻ (.5 ⫻ 100) ⫹ (.5 ⫻

of Treasury bill 105) ⫽ 101.5 90) ⫽ 95 123) ⫽ 111.5

& long-term

bond

Medium-term 101.5 101.5 ⫺ 6.5 ⫽ 95 101.5 ⫹ 10 ⫽

bond 111.5

Our example is grossly oversimplified, but you have probably already noticed

that the basic idea is the same that we used when valuing an option. To value an

option on a share, we constructed a portfolio of a risk-free loan and the common

stock that would exactly replicate the payoffs from the option. That allowed us to

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

VII. Debt Financing 24. Valuing Debt

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

price the option given the price of the risk-free loan and the share. Here we value a

bond by constructing a portfolio of two or more other bonds that will provide ex-

actly the same payoffs.

23

That allows us to value one bond given the prices of the

other bonds.

Our example carries three messages. First, bond traders focus on changes in bond

prices and on how the changes for different bonds are linked. Second, changes in

bond prices can be related to a small number of factors (in our example, the change

in the overall level of interest rates completely defined the change in the price of

each bond). Third, once the linkages between bond prices can be pinned down,

then each bond can be priced relative to a package of other bonds.

CHAPTER 24

Valuing Debt 683

23

Two early examples of models that use no-arbitrage conditions to model the term structure are

O. Vasicek, “An Equilibrium Characterization of the Term Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 5

(November 1977), pp. 177–188; and J. C. Cox, J. E. Ingersoll, and S. A. Ross, “A Theory of the Term

Structure of Interest Rates,” Econometrica 53 (May 1985), pp. 385–407.

24.5 ALLOWING FOR THE RISK OF DEFAULT

You should by now be familiar with some of the basic ideas about why interest

rates change and why short rates may differ from long rates. It only remains to con-

sider our third question: Why do some borrowers have to pay a higher rate of in-

terest than others?

The answer is obvious: Bond prices go down, and interest rates go up, when the

probability of default increases. But when we say “interest rates go up,” we mean

promised interest rates. If the borrower defaults, the actual interest rate paid to the

lender is less than the promised rate. The expected interest rate may go up with in-

creasing probability of default, but this is not a logical necessity.

These points can be illustrated by a simple numerical example. Suppose that the

interest rate on one-year, risk-free bonds is 9 percent. Backwoods Chemical Com-

pany has issued 9 percent notes with face values of $1,000, maturing in one year.

What will the Backwoods notes sell for?

The answer is easy—if the notes are risk-free, just discount principal ($1,000)

and interest ($90) at 9 percent:

Suppose instead that there is a 20 percent chance that Backwoods will default and

that, if default does occur, holders of its notes receive nothing. In this case, the pos-

sible payoffs to the noteholders are

PV of notes ⫽

$1,000 ⫹ 90

1.09

⫽ $1,

000

Payoff Probability

Full payment $1,090 .8

No payment 0 .2

The expected payment is .

We can value the Backwoods notes like any other risky asset, by discounting their

expected payoff ($872) at the appropriate opportunity cost of capital. We might dis-

count at the risk-free interest rate (9 percent) if Backwoods’s possible default is

.81$1,

0902⫹ .21$02⫽ $872