Boyer George R. An Economic History of the English Poor Law, 1750-1850

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

An Economic Model

of

the English

Poor

Law 107

seasonal layoffs were more likely

to

occur

the

larger

the

share

of the

poor rate paid

by

non-labor-hiring taxpayers.

The

value

of

e

was

deter-

mined

by the

distribution

of

property holdings

in the

parish

and was

therefore largely insulated from parish politics. Because parish authori-

ties determined property assessments, however,

the

political makeup

of

the parish could potentially have affected

the

value

of e. If

those

in

power tended

to

underassess their own property, then,

for a

given distri-

bution

of

property,

e

would have been smaller

in

parishes dominated

by

labor-hiring farmers than

in

parishes dominated

by

taxpayers

who did

not hire labor.

The size

of

poor relief benefits

was

determined

by the

parish vestry.

Recall that unemployed workers received income

d

t

,

which consisted

of

private (severance) payments from farmers

to

workers,

b

n

and

public

relief benefits.

It was

clearly

in the

interest

of

labor-hiring farmers

to

substitute public

for

private

relief,

since public relief was partly paid

for

by non-labor-hiring taxpayers. Where labor-hiring farmers dominated

parish vestries, therefore, unemployed workers should have received

only poor

relief.

Conversely, where vestries were controlled

by

taxpay-

ers

who did not

hire labor, poor relief benefits might have been

set

below

the

efficient level

of d

t

(determined from equation

(7)),

forcing

farmers

to

offer private relief payments

to

workers they laid

off

during

slack seasons.

29

Because

the

level

of

public relief benefits

was set by the

parish vestry,

the

size

of the

poor relief subsidy

and,

therefore,

the

number

of

layoffs were partly determined

by the

political makeup

of the

parish.

For any

given values

of e and x

n

the

number

of

layoffs should

have been larger

in

parishes dominated

by

labor-hiring farmers than

in

parishes dominated

by

taxpayers

who did not

hire labor.

The model shows that layoffs should never occur

if

s

= 0.

This result

may appear surprising

at

first,

but it has an

intuitive explanation.

Con-

sider

an

allocation

of

labor hours

in

which there

is

less than full employ-

ment, which yields

an

expected utility

V for

each worker

and a

profit

TT'

for

the

farmer. Suppose this allocation

of

labor hours

is

replaced

by a

new allocation

in

which

all

workers

are

employed,

and

hours

per

worker

are reduced

by

enough

to

equate total labor hours across

the two

alloca-

tions.

If

s

=

0 and the

total man-hours worked

are the

same,

the

farmer's

profits

are the

same

for

both allocations,

and he

should

be

indifferent

29

Private relief benefits typically took

the

form

of

allotments

of

land

or

potato ground

offered

by

farmers

to

their workers

at

zero

or

below-market rent.

108 An Economic History of

the

English Poor Law

between them.

30

However, because workers are risk averse, they prefer

the new allocation of labor, which assures them employment, despite the

fact that the expected income from the two contracts is the same. Thus,

full-employment contracts are always dominant if

s

= 0, that is, if labor-

hiring farmers are the only parish taxpayers (e = 1) or poor relief is not

given to able-bodied workers (g = 0).

One other result obtained from the model should be mentioned. Re-

call that the farmer is assumed to enter into an agreement (implicit

contract) with N workers, where N does not necessarily equal all the

workers in the parish (that is, N ^ 1). The size of N is determined by the

following equation

EX

t

{fMxMx,)*Mx<)

~

c<(x

t

)

+ [1 -

n

t

(x

t

)/N]z

t

(x

t

)}

- y = 0

where y is the Lagrangian multiplier associated with the constraint

TV

<

1. When N < 1, y = 0, and the optimal number of workers under

contract is determined by equating the average output from the marginal

worker to the average cost of hiring him, which is his consumption net of

the amount he is willing to pay not to be laid off times the probability of

layoff.

31

All workers in the parish will be under contract if the average

output from the marginal worker is sufficiently high.

If N < 1, the parish contained more able-bodied workers than it

needed. By law the parish was under an obligation to offer poor relief to

all persons unable to provide for themselves. But it was not necessary to

provide all persons with outdoor

relief.

It was in the ratepayers' interest

to force chronically unemployed workers either to perform onerous

tasks or to enter a workhouse in order to obtain

relief.

The purpose of

such tactics was to ensure that the expected utility of redundant workers

was less than V*, and thus to cause them to leave the parish. In this way

the parish vestry was able to maintain the resident work force at approxi-

mately the number of workers needed by labor-hiring farmers.

Up to this point I have assumed that cottage industry did not exist in

the parish. However, although wage rates and employment opportuni-

30

If s > 0, the

farmer's profits

are

larger under

the

original allocation

of

labor time,

because workers

on

layoff

are

supported

in

part

by

non-labor-hiring taxpayers.

31

Burdett

and

Wright (1989b) show that

the

number

of

workers under contract

is

nega-

tively related

to the

value

of a

firm's experience-rating factor, which

is

essentially

the

same

as e in my

model. That

is, the

firm's long-run demand

for

labor

is

affected

by the

marginal

tax

cost

of

layoffs.

In

terms

of my

model,

an

increase

in the

share

of the

poor

rate paid

by

non-labor-hiring taxpayers would increase

the

number

of

workers

the

farmer offered

a

contract,

N.

An Economic Model of

the

English Poor Law 109

ties in cottage industry declined sharply after 1780, women and children

were still employed at straw plaiting, lacemaking, and the like, in parts

of the rural south in 1832.

32

Cottage industry can be incorporated into

the model by including the utility obtained from such employment,

V{H),

in the workers' utility constraint faced by the farmer, as follows

ES

t

V

t

(x

t

) > V* - V(H)

The existence of nonagricultural employment opportunities for women

and children reduced the utility value of the implicit contract farmers

had to offer their workers to keep them from leaving the parish. Agricul-

tural wage rates or relief benefits should have been lower in parishes

with cottage industry than in parishes without cottage industry, other

things equal.

c. Summary of

the

Model's Results

The model developed in this section shows that implicit contracts con-

taining seasonal layoffs and poor relief payments to unemployed work-

ers were cost-minimizing for labor-hiring farmers only under certain

conditions. The major determinants of the form of farmers' profit-

maximizing labor contracts were the extent of seasonal fluctuations in

the demand for labor (a function of crop mix), the share of the poor

rate paid by non-labor-hiring taxpayers, and the political makeup of

the parish. In grain-producing areas, where the demand for labor fluctu-

ated sharply over the crop cycle, farmers minimized labor costs by

laying off unneeded workers during slack seasons and having them

collect poor

relief.

Full-employment contracts were cost-minimizing in

pasture-farming areas, where the demand for labor was spread rela-

tively evenly over the year.

For any given crop mix, the larger the contribution of non-labor-

hiring taxpayers to the poor rate, the lower the cost to farmers of laying

off workers and the larger the number of layoffs. The contribution of

non-labor-hiring taxpayers was determined by the distribution of prop-

erty holdings in the parish and by the size of relief benefits paid to

unemployed workers. The latter was set by the parish vestry and there-

fore was affected by the political makeup of the parish.

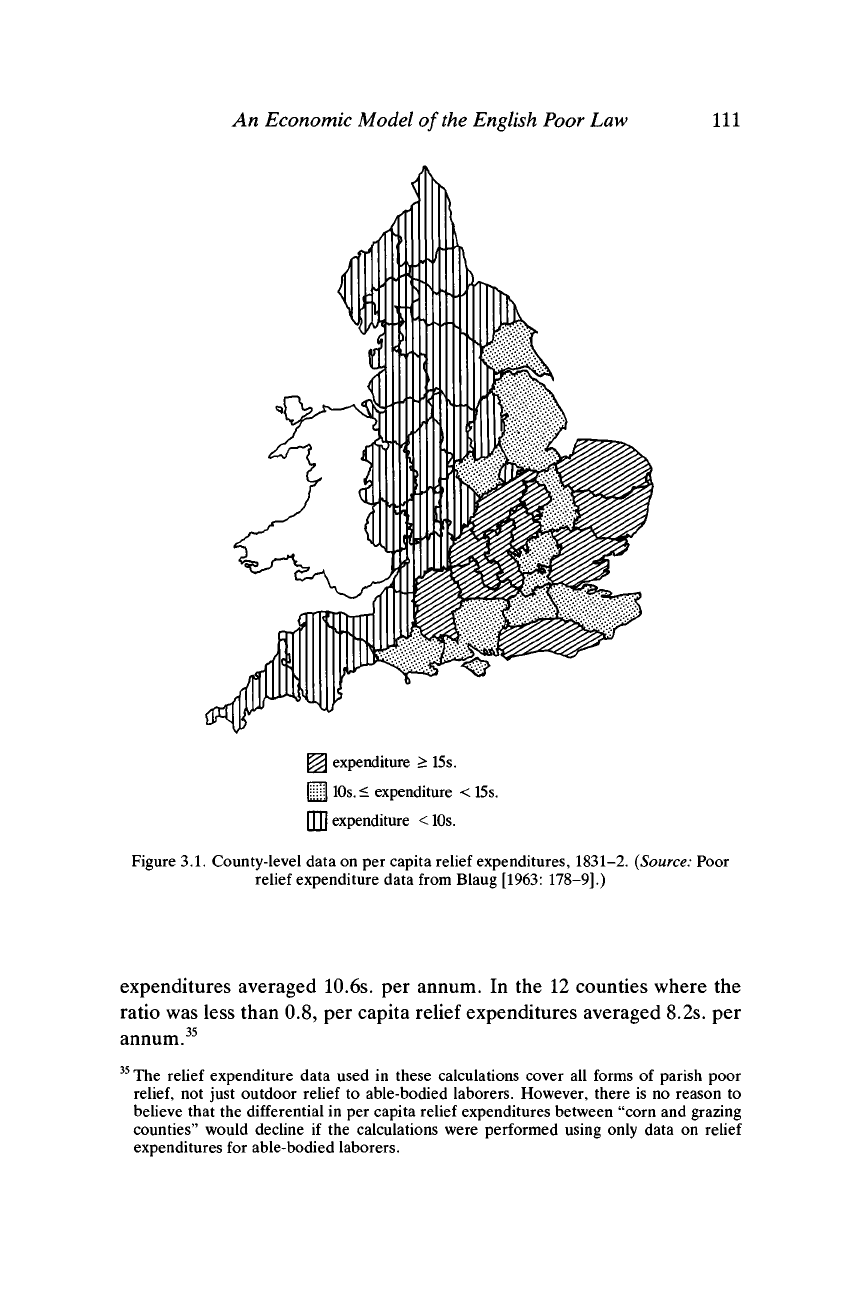

County-level data on per capita relief expenditures and information

32

See

Chapter

1,

Section

3.

110

An

Economic History

of

the English

Poor

Law

on regional variations

in the

length

of

labor contracts suggest that,

on

average, labor-hiring farmers responded

in a

cost-minimizing manner

to

the economic environment. Explicit yearlong labor contracts remained

widespread

in

pasture-farming areas throughout

the

Speenhamland

era,

while weekly

(or

even daily) contracts became predominant

in the

south

and east during

the

last

few

decades

of

the eighteenth century (Hasbach

1908:

176-8,

262-3,

329;

Hobsbawm

and

Rude

1968: 40,

43-4).

The

absence

of

yearlong contracts

in

grain-producing areas suggests that

farmers were indeed laying

off

laborers during certain seasons.

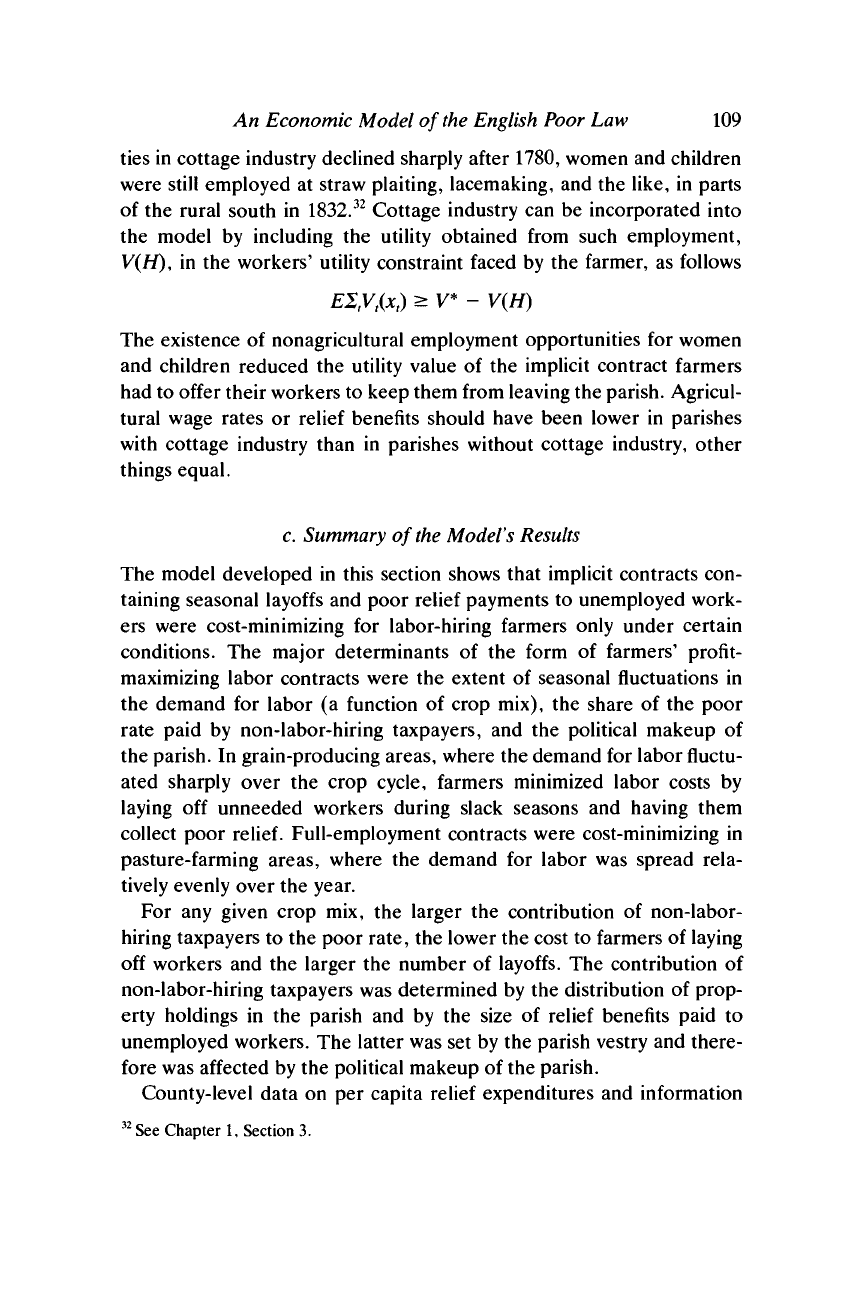

There

is

also

a

strong positive correlation,

at the

county level

of

aggregation, between

per

capita poor relief expenditures

and the

impor-

tance

of

grain production.

33

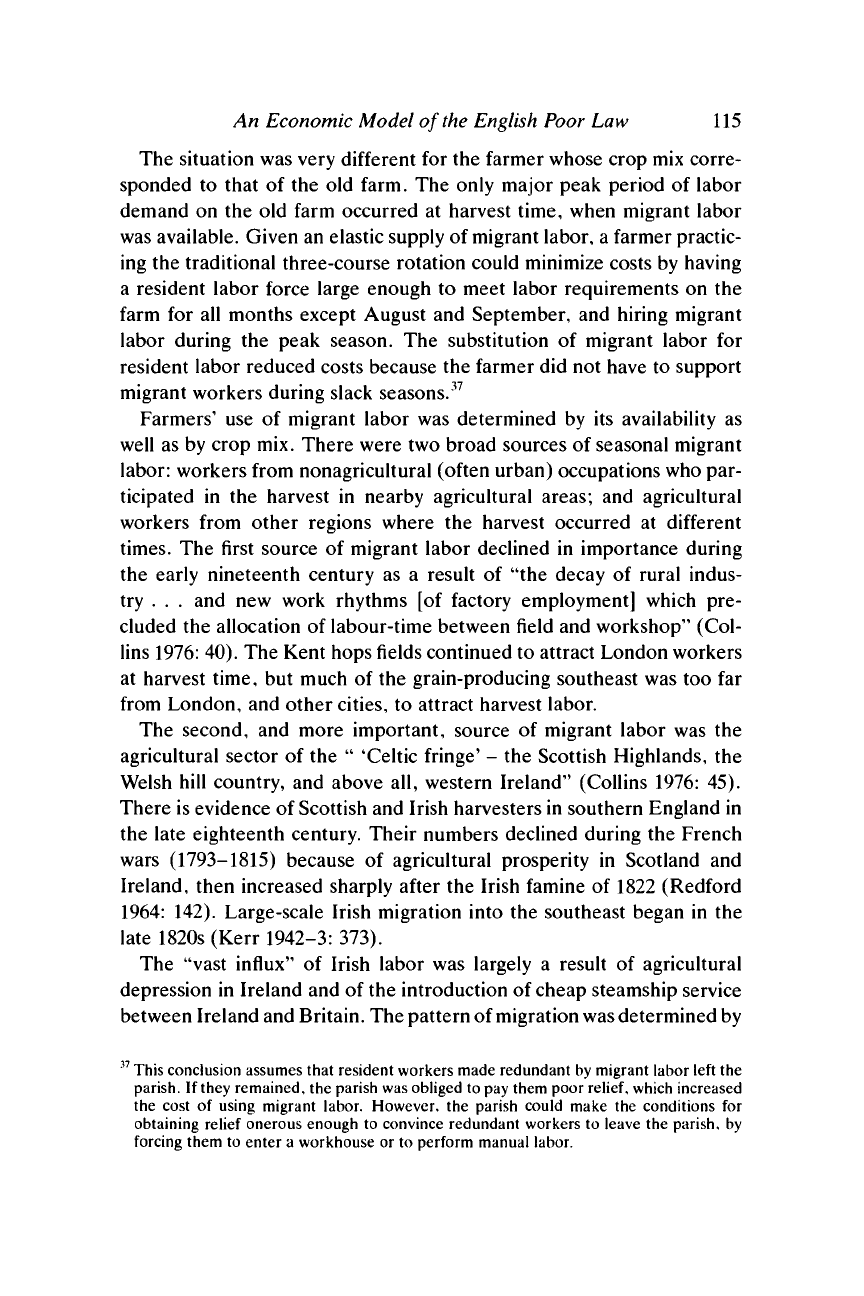

Figure 3.1 presents county-level data

on per

capita relief expenditures

in

1831. There

is a

clear regional aspect

to the

level

of per

capita expenditures, which were significantly higher

in the

southeast than

in the

west

or

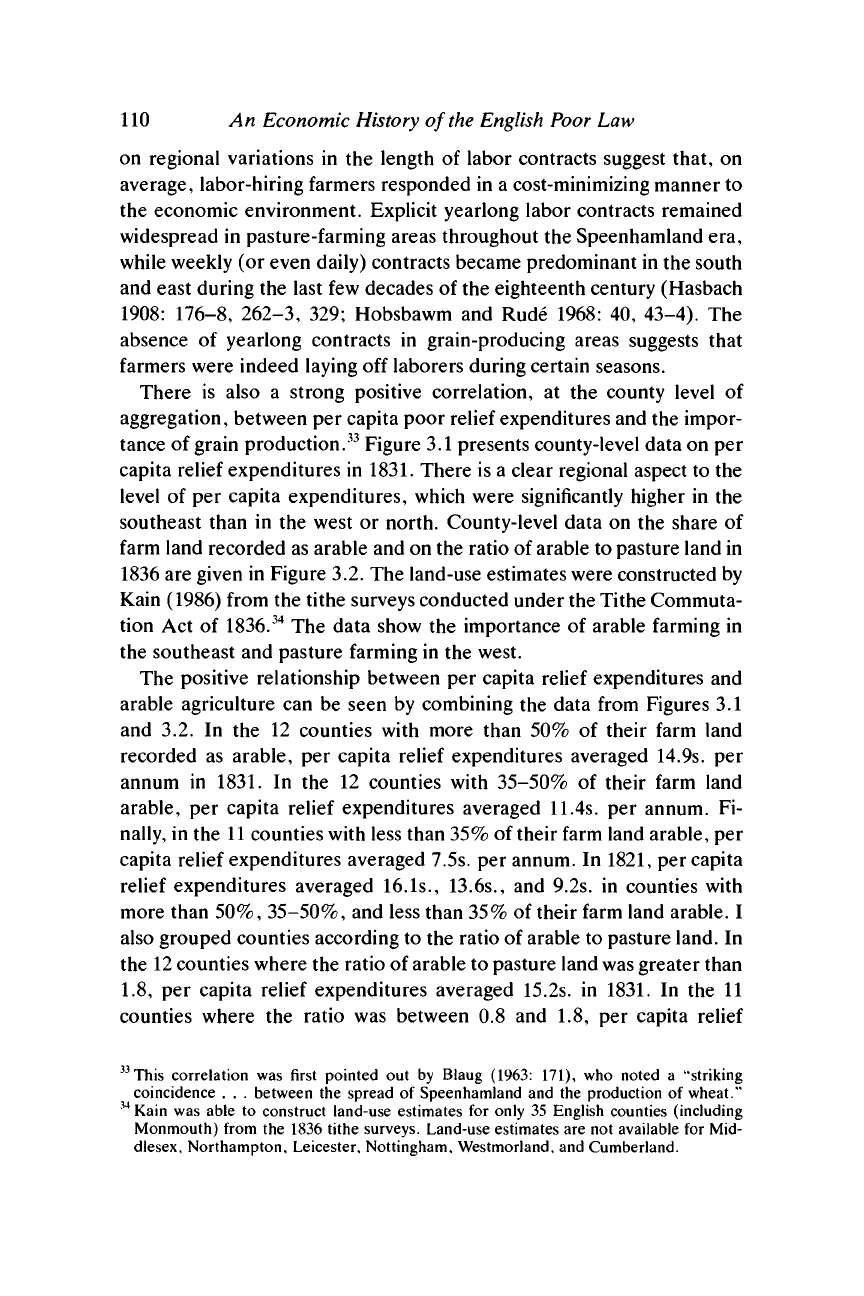

north. County-level data

on the

share

of

farm land recorded

as

arable

and on the

ratio

of

arable

to

pasture land

in

1836

are

given

in

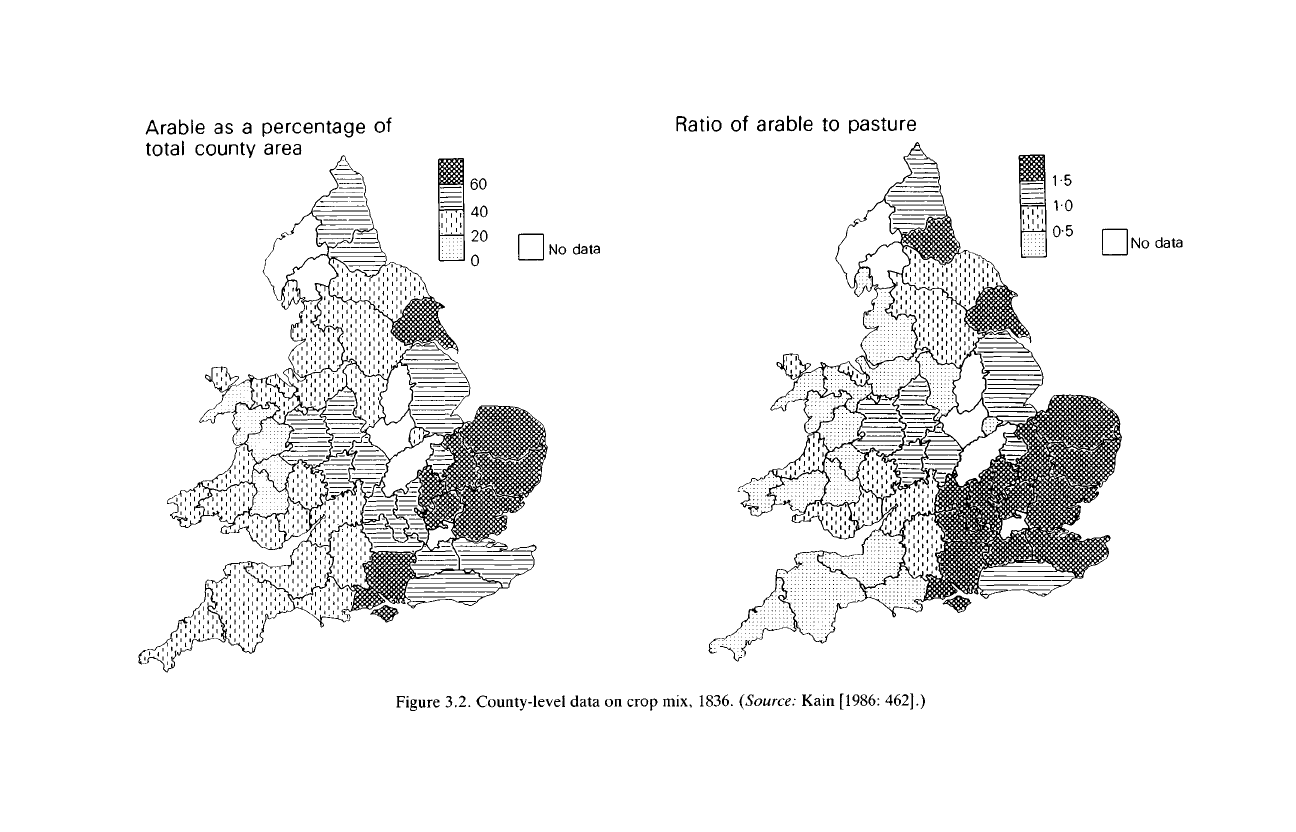

Figure 3.2.

The

land-use estimates were constructed

by

Kain (1986) from

the

tithe surveys conducted under the Tithe Commuta-

tion

Act of

1836.

34

The

data show

the

importance

of

arable farming

in

the southeast

and

pasture farming

in the

west.

The positive relationship between

per

capita relief expenditures

and

arable agriculture

can be

seen

by

combining

the

data from Figures

3.1

and

3.2. In the 12

counties with more than

50% of

their farm land

recorded

as

arable,

per

capita relief expenditures averaged 14.9s.

per

annum

in 1831. In the 12

counties with 35-50%

of

their farm land

arable,

per

capita relief expenditures averaged 11.4s.

per

annum.

Fi-

nally,

in the

11

counties with less than

35%

of

their farm land arable,

per

capita relief expenditures averaged 7.5s.

per

annum.

In

1821,

per

capita

relief expenditures averaged 16.1s., 13.6s.,

and 9.2s. in

counties with

more than 50%, 35-50%,

and

less than 35%

of

their farm land arable.

I

also grouped counties according

to the

ratio

of

arable

to

pasture land.

In

the

12

counties where

the

ratio

of

arable

to

pasture land was greater than

1.8, per

capita relief expenditures averaged 15.2s.

in 1831. In the 11

counties where

the

ratio

was

between

0.8 and 1.8, per

capita relief

33

This correlation was first pointed out by Blaug

(1963:

171), who noted a "striking

coincidence . . . between the spread of Speenhamland and the production of wheat."

34

Kain was able to construct land-use estimates for only 35 English counties (including

Monmouth) from the 1836 tithe surveys. Land-use estimates are not available for Mid-

dlesex, Northampton, Leicester, Nottingham, Westmorland, and Cumberland.

An Economic Model of the

English Poor

Law

111

^ expenditure > 15 s.

J

10s.

£ expenditure < 15s.

[JJ]

expenditure <10s.

Figure

3.1.

County-level data on per capita relief expenditures, 1831-2.

(Source:

Poor

relief expenditure data from Blaug

[1963:

178-9].)

expenditures averaged 10.6s. per annum. In the 12 counties where the

ratio was less than 0.8, per capita relief expenditures averaged 8.2s. per

annum.

35

The relief expenditure data used in these calculations cover all forms of parish poor

relief,

not just outdoor relief to able-bodied laborers. However, there is no reason to

believe that the differential in per capita relief expenditures between "corn and grazing

counties" would decline if the calculations were performed using only data on relief

expenditures for able-bodied laborers.

Arable as a percentage of

total county area

r

Ratio of arable to pasture

•

No data

No data

Figure 3.2. County-level data on crop mix, 1836. (Source: Kain [1986: 462].)

An Economic Model of

the English

Poor Law

5. The Effect of Migrant Labor on the Rural Labor Market

113

The model developed in Section 4 assumed that farmers only employed

workers who resided in the parish during the entire year. But profit-

maximizing farmers might have preferred to reduce the resident labor

force and hire migrant labor at harvest time rather than to maintain a

resident labor force large enough to meet peak-season labor require-

ments. The attractiveness of the former policy depended on the elastic-

ity of the supply curve of migrant labor and on the seasonal distribution

of labor requirements in agriculture.

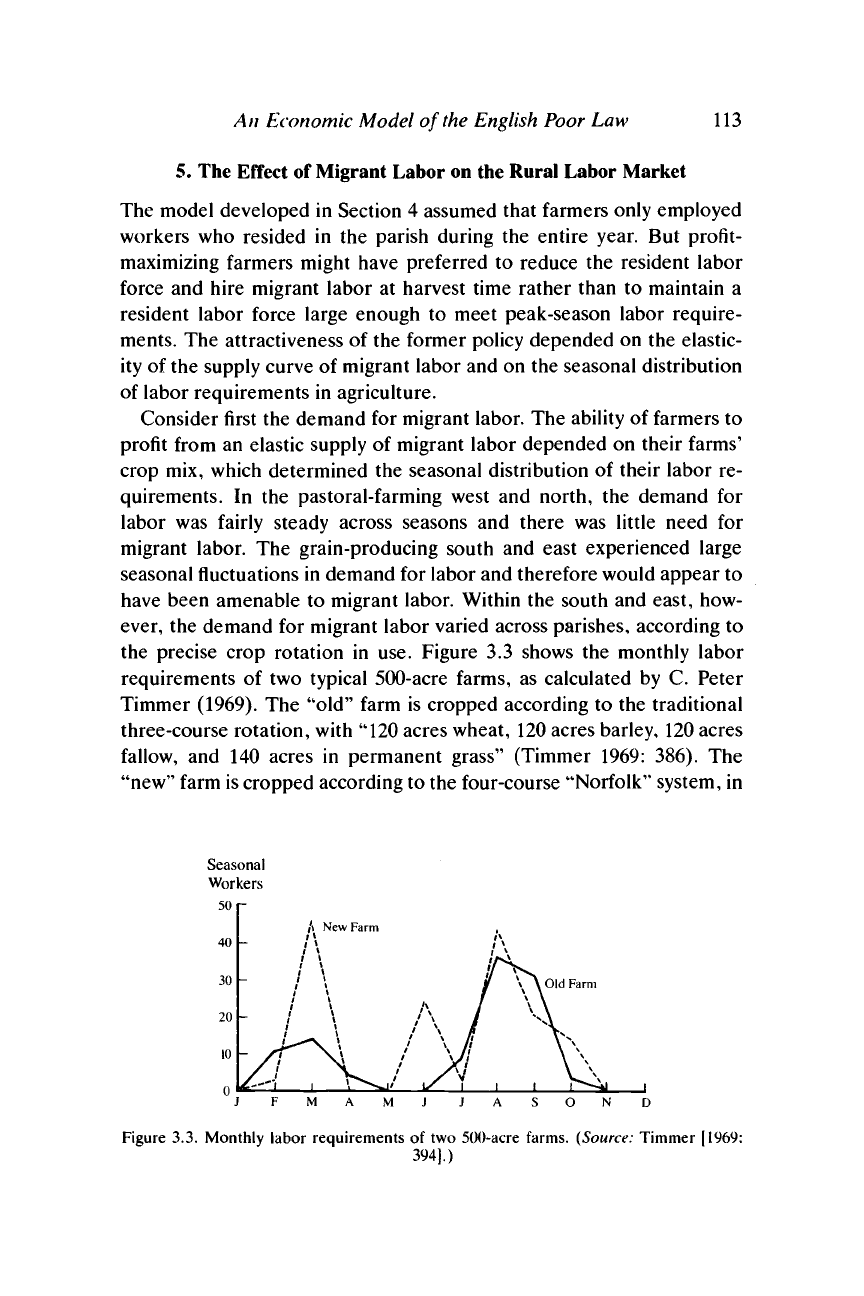

Consider first the demand for migrant labor. The ability of farmers to

profit from an elastic supply of migrant labor depended on their farms'

crop mix, which determined the seasonal distribution of their labor re-

quirements. In the pastoral-farming west and north, the demand for

labor was fairly steady across seasons and there was little need for

migrant labor. The grain-producing south and east experienced large

seasonal fluctuations in demand for labor and therefore would appear to

have been amenable to migrant labor. Within the south and east, how-

ever, the demand for migrant labor varied across parishes, according to

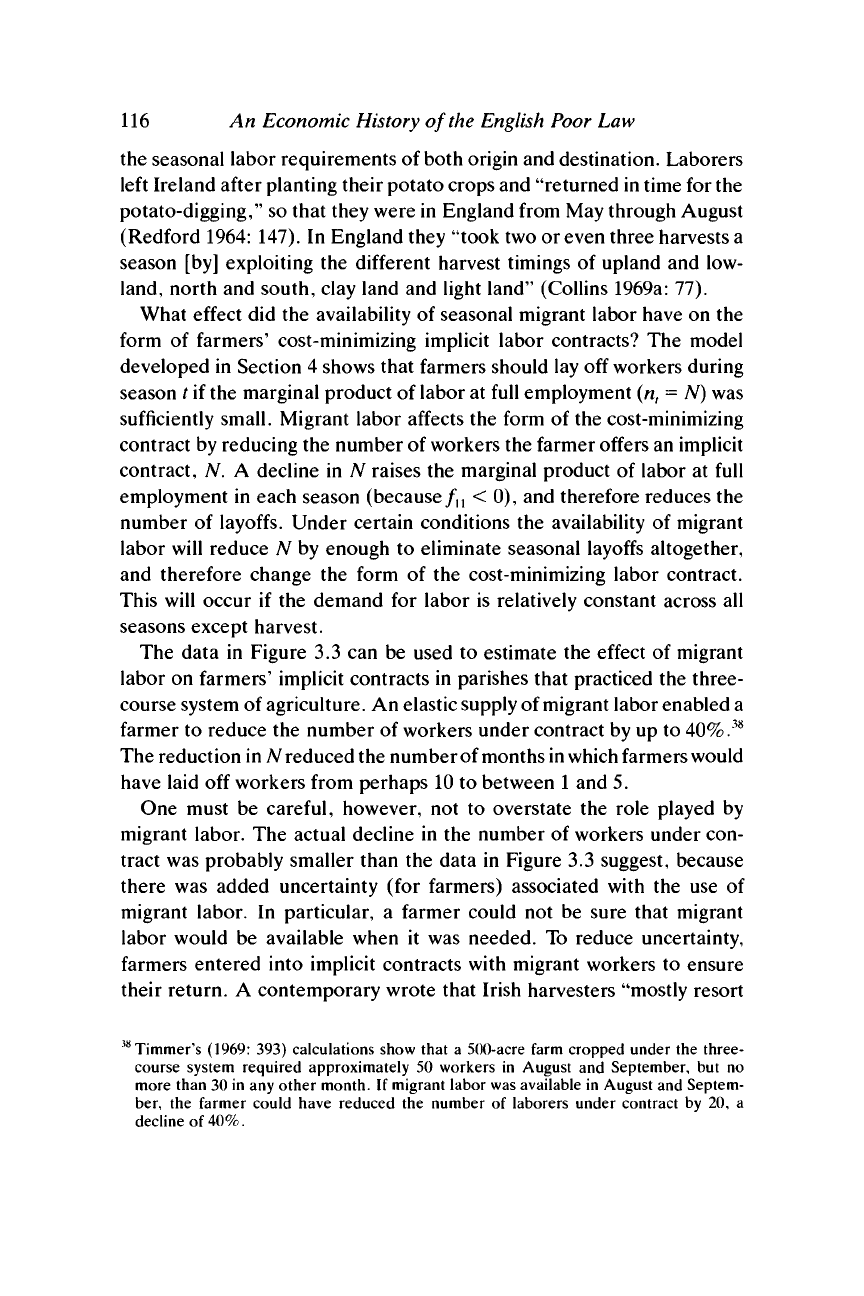

the precise crop rotation in use. Figure 3.3 shows the monthly labor

requirements of two typical 500-acre farms, as calculated by C. Peter

Timmer (1969). The "old" farm is cropped according to the traditional

three-course rotation, with "120 acres wheat, 120 acres barley, 120 acres

fallow, and 140 acres in permanent grass" (Timmer 1969: 386). The

"new" farm is cropped according to the four-course "Norfolk" system, in

Old Farm

Figure 3.3. Monthly labor requirements of two 500-acre farms. (Source: Timmer [1969:

394].)

114 An Economic History of the

English Poor

Law

which the 260 acres of fallow and permanent grass are replaced by 120

acres of turnips, 120 acres of clover, and 20 acres of permanent grass.

The transition from the three-course system of cultivation to the four-

course system began on the well-drained, thin, and infertile soils of "the

home counties, East Anglia, and much of Southern England" during the

late seventeenth century (Chambers and Mingay 1966: 59). The number

of southern and eastern farms practicing the Norfolk system substan-

tially increased during the eighteenth century, although the traditional

three-course technique continued to be used in areas that received large

amounts of rainfall or had soils unamenable to the new rotation.

36

The adoption of the Norfolk system had an important effect on the

seasonal distribution of labor requirements. As seen in Figure 3.3, the

cultivation of turnips on the new farm led to two new peak periods of

labor demand, in March and June. The increased demand for labor

during the early spring made the new farm much less amenable to the

use of seasonal migrant labor than was the old farm. A farm practicing

the Norfolk system required as many laborers in March as it did in

August, but migrant labor generally was available only during the sum-

mer. Thus, a farmer whose crop mix corresponded to that of the new

farm would require a resident labor force as large as his harvest labor

force.

Farmers using the Norfolk system had the option of using migrant

labor instead of resident labor at harvest time, but any reduction in

resident laborers' harvest earnings had to be made up either in poor

relief or in higher wages during other seasons, in order to maintain

workers' expected utility at its reservation level. So long as farmers

could not use migrant labor to reduce the number of workers under

contract, it was cheaper to use resident labor rather than migrant labor

at harvest time. According to E. J. T. Collins (1976: 56)

As a general rule outsiders were not taken on until all local labour was fully

employed and custom decreed that first refusal of casual work was given to the

wives and dependents of permanent workers. Farmers were anyhow mindful of

the connexion between earnings in summer and poor relief in winter, and, thus

cautioned, were loath to interfere in what were commonly regarded as the

"rights of labor."

36

According to Chambers and Mingay (1966: 58), "the difficulty of growing roots and the

new legumes and grasses on ... the wet and cold clays provided a serious and persistent

obstacle to agricultural progress in the midland clay triangle and other districts of similar

soils.

... Of necessity, two crops and a fallow remained the basic rotation on them . . .

until cheap under-drainage came in towards the middle of the nineteenth century."

An Economic Model of

the English Poor

Law 115

The situation was very different for the farmer whose crop mix corre-

sponded to that of the old farm. The only major peak period of labor

demand on the old farm occurred at harvest time, when migrant labor

was available. Given an elastic supply of migrant labor, a farmer practic-

ing the traditional three-course rotation could minimize costs by having

a resident labor force large enough to meet labor requirements on the

farm for all months except August and September, and hiring migrant

labor during the peak season. The substitution of migrant labor for

resident labor reduced costs because the farmer did not have to support

migrant workers during slack seasons.

37

Farmers

7

use of migrant labor was determined by its availability as

well as by crop mix. There were two broad sources of seasonal migrant

labor: workers from nonagricultural (often urban) occupations who par-

ticipated in the harvest in nearby agricultural areas; and agricultural

workers from other regions where the harvest occurred at different

times.

The first source of migrant labor declined in importance during

the early nineteenth century as a result of "the decay of rural indus-

try ... and new work rhythms [of factory employment] which pre-

cluded the allocation of labour-time between field and workshop" (Col-

lins 1976: 40). The Kent hops

fields

continued to attract London workers

at harvest time, but much of the grain-producing southeast was too far

from London, and other cities, to attract harvest labor.

The second, and more important, source of migrant labor was the

agricultural sector of the " 'Celtic fringe' - the Scottish Highlands, the

Welsh hill country, and above all, western Ireland" (Collins 1976: 45).

There is evidence of Scottish and Irish harvesters in southern England in

the late eighteenth century. Their numbers declined during the French

wars (1793-1815) because of agricultural prosperity in Scotland and

Ireland, then increased sharply after the Irish famine of 1822 (Redford

1964:

142). Large-scale Irish migration into the southeast began in the

late 1820s (Kerr 1942-3: 373).

The "vast influx" of Irish labor was largely a result of agricultural

depression in Ireland and of the introduction of cheap steamship service

between Ireland and Britain. The pattern of migration

was

determined by

37

This conclusion assumes that resident workers made redundant by migrant labor left the

parish. If they remained, the parish was obliged to pay them poor

relief,

which increased

the cost of using migrant labor. However, the parish could make the conditions for

obtaining relief onerous enough to convince redundant workers to leave the parish, by

forcing them to enter a workhouse or to perform manual labor.

116 An Economic History of the

English

Poor Law

the seasonal labor requirements of both origin and destination. Laborers

left Ireland after planting their potato crops and "returned in time for the

potato-digging," so that they were in England from May through August

(Redford 1964: 147). In England they "took two or even three harvests a

season [by] exploiting the different harvest timings of upland and low-

land, north and south, clay land and light land" (Collins 1969a: 77).

What effect did the availability of seasonal migrant labor have on the

form of farmers' cost-minimizing implicit labor contracts? The model

developed in Section 4 shows that farmers should lay off workers during

season t if the marginal product of labor at full employment (n

t

= N) was

sufficiently small. Migrant labor affects the form of the cost-minimizing

contract by reducing the number of workers the farmer offers an implicit

contract, N. A decline in

TV

raises the marginal product of labor at full

employment in each season (because f

n

< 0), and therefore reduces the

number of layoffs. Under certain conditions the availability of migrant

labor will reduce

TV

by enough to eliminate seasonal layoffs altogether,

and therefore change the form of the cost-minimizing labor contract.

This will occur if the demand for labor is relatively constant across all

seasons except harvest.

The data in Figure 3.3 can be used to estimate the effect of migrant

labor on farmers' implicit contracts in parishes that practiced the three-

course system of

agriculture.

An elastic supply of migrant labor enabled a

farmer to reduce the number of workers under contract by up to

40%.

38

The reduction in N reduced the number of months

in

which farmers would

have laid off workers from perhaps 10 to between

1

and 5.

One must be careful, however, not to overstate the role played by

migrant labor. The actual decline in the number of workers under con-

tract was probably smaller than the data in Figure 3.3 suggest, because

there was added uncertainty (for farmers) associated with the use of

migrant labor. In particular, a farmer could not be sure that migrant

labor would be available when it was needed. To reduce uncertainty,

farmers entered into implicit contracts with migrant workers to ensure

their return. A contemporary wrote that Irish harvesters "mostly resort

38

Timmer's (1969: 393) calculations show that a 500-acre farm cropped under the three-

course system required approximately 50 workers in August and September, but no

more than 30 in any other month. If migrant labor was available in August and Septem-

ber, the farmer could have reduced the number of laborers under contract by 20, a

decline of 40%.