Borovik A. Shadows of the Truth: Metamathematics of Elementary Mathematics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.3 Dividi ng apples b y apples: a correct answer 5

¸SUE only made his peace with remainders during his first year

at university, when the process of division with remainder was in-

troduced as a fo rmal technique. He is not alone in waiting years be-

fore finally being told that division with remainder is not a binary

operation because it produces two outputs, not one, as a binary op-

eration should: partial quotient and r emainder. Inde ed here is a

story from D an G arr y

4

:

When I was seven, I had to take a week off because I was sick. We

were studyin g division at the time, and during the week I missed,

the concept of remainders was covered. I asked the teacher what a

“remainder” was and sh e was rather dismissive, saying “It’s what’s

left over when you divide”. This made absolutely no sense to me;

I remember thinking “7 divided by 3 is 2, what exactly is there

to be left over?”. Looking back on it, it occurs to me that I was

thinking of division as a binary operation: 7 di vided by 3 is exactly

2. As silly as it might s ound, I never really figured out the rela-

tion between “division” and “remainders” of integers until I went

to a lecture on the division algorithm in my first year of uni versity,

which conveniently took place a few hours after a lecture in com-

puter science about how the JAVA programming language handles

integer division.

1.3 Divi ding apples by apples: a correct answer

But let us return to com paring problems (1.1) and (1.2). In the fi rst

problem you have a fixed data set: 10 apples and 5 people, and you

can easily visualize giving apples to the people, in rounds, one ap-

ple to a person at a time, until no apples were left. But, as I have

already mentioned, an attempt to visualize the second problem in

a similar way, as an orderly distribution of apples to a queue of

people, two apples to e ach person, necessitates dealing with a po-

tentially unlimited number of recipients.

I asked my teacher for h elp, but did not get a satisfactory an-

swer. Only much later did I realize that the corr ect namin g of the

numbers should be

10 ap ples : 5 people = 2

apples

people

, 10 ap ples : 2

apples

people

= 5 people.

(1.3)

I was no t alone in my discomfort with “named numbers” and

“units”. Here is a testimony f rom John Gibbon

5

:

4

DG is male, 21 years old, was born and raised in England. He is a final

year un d ergradu ate studying Computer Science and Mathematics in a

British university.

5

JDG is male, British, a professor of ap plied mathematics.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

6 1 Dividing Apples between People

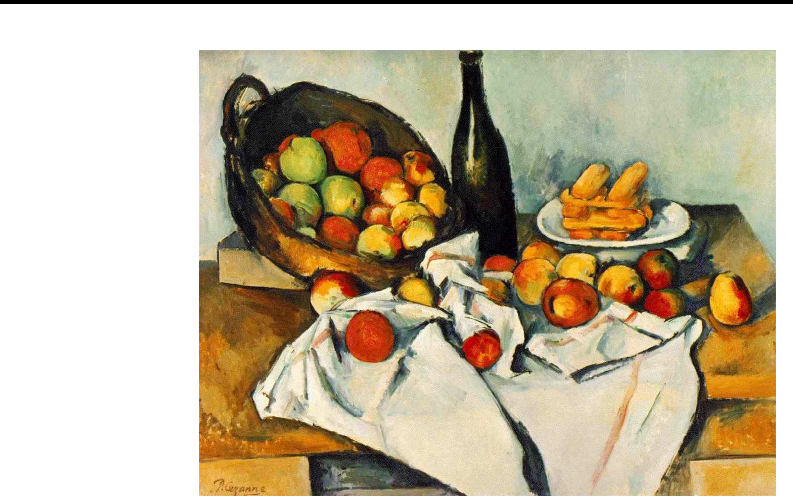

Fig. 1.2. Paul Cézanne. Still Life with Ba sket of Apples. 1890–94. The Art

Institute of Chicago. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

At the age of 6 years I was asked the question “How many oranges

make 5?”. I recall that I refused to answer. This indicated to her

that I was unintelligent, which had been her worry. Later in life

I realized why my 6 year-old mind had felt there was something

wrong with the question. The issue was one of units: “How many

oranges make 5 what?” was the problem turning round in my 6

year-old mind. On the one hand one cannot change oranges into

something else so I rejected “How many oranges make 5 ap ples?”

On the other hand, if the answer was “How many oranges make 5

oranges?” then we had a tautology. I did not know what a tauto-

logical argument was but I knew I felt uncomfortable with it.

Therefore let us look into equations (1.3) with some attention.

1.4 What ar e the numbers children are working

with?

It is a commo nplace wisdom that the deve lopment of mathemati-

cal skills in a student goes alongside the gradual expansion of the

realm of numbers with which he or she works, from natural num-

bers to integ ers, then to rational, real, complex numbers:

N ⊂ Z ⊂ Q ⊂ R ⊂ C.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

1.4 What are the numbers children are working with? 7

What is missing from this natural hierarchy is that already at

the level of elementary school arithmetic children are working in

a much more sophisticated structure, a graded ring

Q[x

1

, x

−1

1

, . . . , x

n

, x

−1

n

].

of Laurent polynomials

6

in n variables over Q, where symbols

x

1

, . . . , x

n

stand for the names of objects involved in the calculation: apples,

persons, etc. This explains why educational psychologists confi-

dently claim that the operations (1.1) and (1.2) on Page 1 have little

in common [255]—indeed, operation (1.2) involves an operand “ap-

ple/people” of a much more complex nature than basic “apples” and

“people” in operation (1.1): “apple/people” could appear only as a

result of some previous division.

This difficulty was identified already by François Viéte who in

1591 wrote in his Introdu ction to the Analytic Art [229] that

If one magnitude is divided by another, [the quotient] is heteroge-

neous to the former . . . Much of the fogginess and obscurity of the

old ana lysts is due to their not paying attention to these [ru les].

Of course, there is no need to teach Laurent polynomials to kids

(or even to teachers); but we need some simple comm on language

that ad dresses the subtleties without adding unnecessary sophis-

tication. This is why I devote Chapters 3 and 4 to discussion of di-

mensional analysis, that is, the use of “named ” numbers in physics.

To my taste, it provides a nu mber of interesting elementary exam-

ples that m ay be use d if not at school but then at least in teachers’

training.

This need for proper language for elemen tary school arithmetic

is emphasized by Ron Aharoni [595]:

Beside th e four classic operations there is a fifth one, more basic

and important: that of forming a unit. Taking a part of the world

and declaring it to be the “whole”. This operation is at the base of

much of the mathematics of primary school. First of all, in count-

ing: when you have another such unit you say you have “two”, and

so on. The operation of multiplication is based on taking a set,

declaring that this is the unit, and repeati ng it. The concept of a

fraction starts from h aving a whol e, from whi ch parts are taken.

6

Laurent polynomials and Laurent series are named after French mili-

tary engineer Pierre Alphonse Laurent (1813–1854) who was the first

to introduce th em. Another his major achievement was construction of

the port of Le Havre.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

8 1 Dividing Apples between People

At the “adult” leve l, “forming a unit” may be viewed as setting

up an appropriate Laurent polynomial ring as an ambient struc-

ture for a particular arithmetic problem. Later we shall see that,

once we set up a structure, it inevitably comes into interaction with

other structures, thus leading to some (very elementary and ther e-

fore very important) category theory coming into play (see Chap-

ter 7).

1.5 The lunch bag arithmetic, or addition of

heterogeneous quantities

Usually, only Laurent monomials are interpreted as having phy si-

cal (or real life) m eaning. But the addition of heterogeneous quan-

tities still makes sense and is done componentwise: if you h ave

a lunch bag with (2 apples + 1 orange), and another bag, with

(1 apple + 1 orange), together they make

(2 apples +1 orange)+(1 apple +1 orange) = (3 apples +2 or an ges).

Notice that the “lunch bag” metaphor gives a very intuitive and

straightforward approach to vectors: a lunch bag is a vector (at

least this is how vectors are used in econometrics and mathemati-

cal economics).

1.6 Duality and pairing

The “lunch bag” approach to vectors allows a natural introduc-

tion of duality and tensors: the total cost of a purchase of amounts

g

1

, g

2

, g

3

of some goods at prices p

1

, p

2

, p

3

is a “scalar pro duct”-type

7

expression

X

g

i

p

i

.

We see that the quantities g

i

and p

i

could be of com pletely d ifferent

nature. In physics, as a ru le, the dot pr oduct involves heteroge-

neous magnitudes. In introductory physics courses, the dot product

usually makes its first appearance on the scene as w ork done by

moving an obje c t, which is the dot p roduct of the force applied and

the displaceme nt of the object.

The standard treatment of scalar (dot) product of vectors in un-

dergraduate linear algebra usually conceals the fact that dot prod-

uct is a manifestation of duality or pairing of vector spaces, thu s

7

Scalar product is a lso called dot product or inner product.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

1.6 Duality and pairing 9

creating immense difficu lties in the subsequent study of ten sor al-

gebra. As the following testimony from CB

8

shows, the boredom

and confusion start even earlier:

I remember the very first conceptual diffi culty I ever had: that was

the scalar product of vectors. I could not figure why an operation

involving two vectors should yield a plai n number, and my teach-

ers could not expla in what that number meant in relation to the

two vectors. As a result I hated scalar products as all we did with

them was a meaningless if easy algebraic manipulation.

Indeed scalar (or dot) produ c t as it appears in physics is a pair-

ing of two vector spaces U and V of different nature; assuming that

we are working over the re al num bers R, pairing is a map

U × V → R

(u, v) 7→ u · v

which is bilinear, that is,

(au

1

+ bu

2

) · v = au

1

· v + bu

2

· v

and similarly

u · (av

1

+ bv

2

) = au · v

1

+ bu · v

2

,

in both cases f or all a, b ∈ R and all vectors u, u

i

∈ U and v, v

i

∈ V .

If it is possible to ignore physical (or financial) meanings of the

vector spaces U and V , then the two spaces become logically undis-

tinguishable. Paradoxically, this provides another source of diffi-

culty for those students who are sensitive to form al logical aspects

of mathematical concepts.

Here is a testimony from BB

9

:

From the time I learned matrices (age 16 or so) I cannot remember

which are the columns and which are the rows. Given that the ar-

rangement of coefficients in a linear transformation can be written

equally well in a matrix in two ways, it is something that always

takes me 10–15 seconds to recall even now.

Of course, BB has reasons to be confused: for a mathematician,

a matrix is an element in the tensor product V ⊗ V

∗

of a finite

dimensional vector space V and its dual V

∗

. Since the dual of the

8

CB is female, holds a PhD, works as an editorial director in a math-

ematics publishing house. Her mother tongue is French, but she was

educated in English. The episode described happened at age 1 2.

9

BB is male, Russian, has a PhD from an American university and holds

a research position in a British university.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

10 1 Dividing Apples between People

dual of a finite dime nsional space is the same as the original space,

that is,

(V

∗

)

∗

≃ V

canonically, there is no intrinsic reason to distinguish between V

and V

∗

, that is, betw een the rows and the columns of a square ma-

trix.

PD

10

touches on the same theme:

Does the “transition matrix” transform th e basis or the coordi-

nates? (Actually, many books hide the appearance of the i nverse

of the transpose b y suitably defining the transition matrix. ) Given

a matrix of a linear map, am I writing the ma p between the vector

spaces or between th eir duals?

I discuss these and other confusing issues of logical symmetry

and duality—and their p ossible psychophysiological substrate—in

Chapter 22, Telling Left from Righ t.

1.7 Adding fruits, or the augmentation

homomorphism

There is another approach to addition of heterogeneous quantities

highlighted by my correspo ndent Alex Grad

11

:

I remember that I was taught too that you can’t add apples and

oranges, but I “resolved” the problem saying that

3 apples + 2 oranges = 5 frui ts,

including both categories in one more general, I am curious if that

reflects more interesting notions like in your case Laurent polyno-

mials.

It also has a name in “adult” mathematics: it is the augmentation

homomo rphism

Z[x, x

−1

, y, y

−1

] → Z[z, z

−1

]

x

±1

7→ z

±1

y

±1

7→ z

±1

,

it turns variables x and y in a variable z which might be thought to

be of more general sort.

10

PD is male, Bulgarian, has a PhD in Math emati cs, teaches in an Amer-

ican universi ty.

11

AG is male, Romanian, a student of computer science. His stories can

also be found on Pages 1 4 and 85.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

1.8 Dimensions 11

1.8 Dimensions

He consider’d therefore with himself, to see

if he could find any on e Adjunc t or Property

which was common to all Bodies,

both anim ate and inanimate;

but he found nothing of that Natur e,

but only the Notion of Extension,

and that he perceiv’d was common to all Bodies,

viz. That th e y had all of them

length, breadth, and thickness.

Abu Bakr Ibn Tufail,

The History of Havy Ibn Yaqzan

Translated from the Arabic by Simon Ockley.

Physicists love to work in the Laure nt polynomial ring

R[length

±1

, time

±1

, mass

±1

]

because the y love to measure all physical quantities in combina-

tions (called “dimensions”) of the three basic units: for length, time

and mass. But then even this ring bec omes too small since physi-

cists have to use fractional powers of basic units. For example,

velocity has dimension length/time, while electric charge can be

meaningfully treated as having dimension

mass

1/2

length

3/2

time

.

Indeed , it would be natural to choose our units in such a way

that the permittivity ǫ

0

of free space is dimensionless, then from

Coulomb’s law

F =

1

4πǫ

0

q

1

q

2

r

2

applied to two equal charges q

1

= q

2

= q, we see that q

2

/r

2

has the

dimensions of force.

It pays to be attentive to the dimensions of quantities involve d

in a physical formula: the balance of names of units (dimensions)

on the left and rig ht hand sides may suggest the shape of the for-

mula. Such di mensional analysis quickly leads to immensely deep

results, like, for example, Kolmogorov’s celebrated “5/3 Law” for

the energy spectrum of turbulence, see Chapter 4.3.

Meanwhile, we should not blame schoolteachers for mess with

“named” numbers. Unfortunately, it is a part of a more general tra-

dition of ne glect. In 1999 NASA lost a $125 million Mars orbiter

because a Lockheed Martin engineering team used English units

of measurement (inches and feet) while the ag ency’s team used the

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

12 1 Dividing Apples between People

more conventional metric system (mete rs and millimeters) for a

key spacecraft op eration. Only very recently a programmin g lan-

guage was created, F#, which automatically keeps control of units

of measurement and dimensions of quantities generated in the pro -

cess of computation.

Exercises

Exercise 1.1 To scare the reader into acceptance of the intri nsic diffi-

culty of division, I refer to a paper Division by three [16] by Peter Doyle

and John Conway. I q uote their abstract:

We prove without appeal to the Axiom of Choice that for any sets

A and B, if there is a one-to-one correspondence between 3 × A

and 3 × B then there is a one-to-one correspondence between A

and B. The first such proof, due to Lindenbaum, was announced

by Lindenbaum and Tars ki in 1926, and subsequently ‘lost’; Tarski

published an alternative proof in 1949.

Here, of course, 3 is a set of 3 elements, say, {0, 1, 2}. An exercise

for the reader: prove this in a naive set theory with the Axiom of

Choice.

The following line is repeated in the paper [16] twice:

The moral? There is more to division than repeated subtraction.

Exercise 1.2 Theoretical physicists occasionally u se a system of mea-

surements bas ed on fundamental units:

• s p eed of light c = 299, 792, 458 meters per second,

• gravitational constant G = (6.67428 ±0.00067) ×10

−11

m

3

kg

−1

s

−2

and

• Planck’s constant h = 6.62606896 × 10

−34

m

2

kg · s

−1

.

Express the more common physical units: meter, kilogram, second in terms

of c, G, h—you will get what is known as Planck’s units.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

2

Pedagogical Intermission: Human

Languages

We have had a chance to see in Section 1.2 how children ’s per-

ception of mathematics can be af fected by logical and mathemat-

ical structures (such as systems of numerals) of the language of

mathematics instruction and their mother tongue. In this book, we

shall encoun ter more stories about language. Intrinsic structures of

natural languages are engaged in a delicate interplay with hidde n

structures of mathematics.

For me per so nally, this is a serious practical issue. Every au-

tumn, I teach a foundation year (that is, zero level) mathematics

course to a large class of students which includes 70 foreign stu-

dents from coun tries rang in g fro m Afghanistan to Zambia. Stu-

dents in the course come fro m a wide variety of socioeconomic, cul-

tural, educational and linguistic backgrounds. But what matters

in the context of the this book are invisible differences in the logi-

cal structure o f my students’ mother tongues which may have huge

impact on their perception of mathematics. For example, the con-

nective “or” is strictly ex c lusive in Chinese: “one or another but not

both”, wh ile in English “or” is mostly inclusive: “o ne or another or

perhaps both”. Meanwhile, in mathematics “or” is always inclusive

and corresponds to the expression “and/or” of bureaucratic slang.

In Croatian, there are two connectives “and”: one parall el, to link

verbs for actions executed simultaneously, and ano ther consecu-

tive

1

.

But it is as soon as you approach definite and indefinite arti-

cles that you get in a real linguistic quag mire. In the word s of my

correspondent V

ˇ

C

2

:

[In Croatian, there are] no articles. There are many words that can

“serve” as the indefinite articles (neki=some, for example), but no

1

Rudiments of a “consecutive and” can be found in my native Russian

and traced to the same ancient Slavic origins.

2

V

ˇ

C is male, Croatian, a lecturer in mathematical l ogic and computer

science.

13

14 2 Pedagogical Intermission: Human Languages

particularly suitable word to serve as definite article (except the

adjective odre

¯

deni = definite, I guess ). Many times when speaking

mathematics, I (in desperation) used English articles to convey

meaning (eg. Misliš da si našao a metodu ili the metodu za rješa-

vanje problema tog tipa? = You mean you found a method or the

method for solving problems of that type?)

What is truly astonishing is that subtler linguistic aspects of

mathematics can be felt by children. What follows is a story from

JA

3

.

I was 10 or 11 years old, in the final year of p rimary school in

London. I am a native English speaker. The lesson was about frac-

tions, and we were working on ‘word problems’ (i.e. things like,

how many is one quarter of 36 app les?). The teacher said, “When

we are doing fractions, ‘of’ means ‘multiply”’, and I thought, “No

it doesn’t. ‘Of’ can’t change its meaning just because we are doing

fractions. We are being fooled here.” And in that moment I saw

mathematics as a set of conventions for which this teacher at least

did not have a coherent understanding. I needed to know why the

word ‘of’ and the operation of multiplica tion were linked, and the

teacher could not tell me.

On the other hand, the realization of the linguistic nature of

mathematical dif ficulties can come in later life. This is a testimony

from Alex Grad

4

:

When I was about 9 years old, I fi rst learned at school about frac-

tions, and understood them quite well, but I had difficulties in un-

derstanding the concept of fractions that were bi gger than 1, be-

cause you see we were taught that fra ctions are part of something,

so I coul d understand the concept of, for example 1/3 (you a have

a piece of something you divided in 3 equal pieces and you take

one), but I couldn’t understand what meant 4/3 (how can you take

4 pieces when there are only 3?). Of course I got it in several days,

but I remember that I was baffled at first.

3

JA tells about herself: “Incidentally, I went on to study mathematics at A

level, and began a degree in philosophy and mathematics at university,

but became very disillusioned with the way in which mathematics was

taught, an d simply could not keep up—but I loved phi l osophy, and so

dropped the maths. I re-gained my love of mathematics when I b egan a

PGCE course to become a primary school teacher, a nd have spent the last

25+ years as a lecturer and researcher in mathematics education.”

4

AG is male, Romanian, a student at Computer Science faculty which

belongs to Engineering School. He says about himself: “yes, my occupa-

tion is still somehow related to mathematics, but above that I keep an

interest in mathematics and in the psychology of mathematics and the

philosophy of it”. His stories are quoted also on Pages 1 0 and 85.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK