Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

as spasm, rupture, tumor, achalasia, and reflux can be con-

fused with aortic symptomatology. Tortuosity and athero-

sclerosis of the aorta may have a similar appearance on chest

x-ray. Tumors may widen the mediastinal silhouette, and

pulmonary diseases such as pleural effusions and pulmonary

emboli can cause densities on radiographs that may be diffi-

cult to differentiate from aortic disease. When this occurs,

CT scanning or MRI can be of value. Minor ruptures of the

aortic vasa vasorum can widen the aortic shadow without

actually producing aortic disruption.

Treatment

A. General Measures—The disease extent and, if applicable,

the site of intimal injury should be determined based on clin-

ical examination and studies already available. Patients who

are exsanguinating may require immediate operation based

on chest x-ray findings alone. Others should be evaluated rap-

idly and, if ascending aortic disease or aortic transection is

confirmed, repaired immediately. Many elderly patients with

type B dissections or asymptomatic small (<5 cm) aneurysms

may best be managed initially with medical therapy.

Regardless of disease type, patient age, or initial treat-

ment, vigorous continuous medical control of shear forces

with antihypertensives and negative inotropes is essential if

there is residual abnormal aorta. Patients with aortic transec-

tions and localized aneurysms frequently have curative sur-

gery with no remaining diseased aorta. Commonly, when an

aortic dissection is present, only a portion of the aorta is

repaired, and residual disease requires vigorous treatment

and long-term follow-up.

Since diseases of the thoracic aorta can cause morbidity

and mortality owing to complex disease, significant comor-

bidities, and acuteness of presentation, they provide a logical

potential application for newer catheter-based therapies that

have proliferated in the past decade for the treatment of car-

diovascular disorders. Indeed, endovascular stent grafts have

been used in both elective and emergent settings for thoracic

aortic dissection, aneurysmal disease, and blunt injury to the

thoracic aorta. Furthermore, percutaneous fenestration of

the intimal flap has been performed successfully to restore

perfusion to end organs when ischemia results from dissec-

tion. As long-term results of these therapies become available

and as new technology develops, the indications for the use

of percutaneous-based therapies in diseases of the thoracic

aorta will become clearer.

B. Blood Pressure Control—Rapid, continuous control of

blood pressure and pulse pressure should be pursued aggres-

sively immediately following diagnosis. Systolic blood pres-

sure should be kept below 110 mm Hg systolic. The force of

left ventricular contraction (dP/dt) should be minimized by

administering negative inotropes.

An intraarterial monitoring line is vital during the early

phases of treatment because of the potential for rapid alter-

ations in blood pressure. The arterial line should be used

until documented continuous blood pressure control is

accomplished.

Central venous pressures should be monitored and fluid

status optimized. Patients with severe blood loss, intraperi-

cardial blood and tamponade, or end-organ ischemia may

require volume replacement. Cardiovascular function is fre-

quently labile, and inotropes and vasopressors may be

required while definitive diagnosis is established.

A single, ideal drug applicable to every situation does not

exist, but several aspects of the many available antihyperten-

sives are useful. The rapidity of onset, half-life, potency, dis-

tribution, metabolism, degradation products, side effects, and

physiologic effects all should be considered. Use of a short-

acting vasodilator (eg, IV nitroprusside) in combination with

a negative inotropic agent (eg, IV esmolol) effectively reduces

both blood pressure and the force of blood ejection.

Vasodilators commonly used include nitroprusside,

hydralazine, and nitroglycerin. Nitroprusside is well toler-

ated, extremely potent, rapid-acting, and has a short half-life.

Its disadvantages include an increase in dP/dT when used

alone, elevation of pulmonary shunt, and creation of a toxic

metabolite (cyanide) with prolonged high-dose use.

Hydralazine is longer-acting and available orally, making it a

suitable agent for long-term use. Nitroglycerin decreases car-

diac output and blood pressure through direct venodilation

but has little effect on arterial relaxation. Thus its usefulness

for disorders of the thoracic aorta is limited, and it should

not be regarded as a first-line agent.

β-Blockers are available in short-acting (eg, esmolol) and

long-acting (eg, atenolol) forms. As such, they are usually a

part of both short- and long-term management. Of the many

β-blockers available, esmolol offers the advantage of an

extremely short half-life, allowing precise and frequent dos-

ing adjustments toward optimal blood pressure. Labetalol is

also an efficacious agent because of its blockade of both

β-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptors. With this said, for

acute blood pressure control, β-blocker therapy combined

with sodium nitroprusside, as needed, is regarded as the

therapy of choice.

Calcium blockers produce both decreased blood pressure

and decreased contractility. They are of greatest benefit in

long-term management. Their relatively long half-life limits

use acutely during unstable periods.

Central sympatholytics include trimethaphan, clonidine,

methyldopa, and reserpine. They are used less commonly but

do have a role in acute and chronic care as adjuncts to stan-

dard drug regimens.

Nienaber CA, Eagle KA: Aortic dissection: New frontiers in diag-

nosis and management: I. From etiology to diagnostic strate-

gies. Circulation 2003;108:628–35.

Nienaber CA, Eagle KA: Aortic dissection: New frontiers in diag-

nosis and management: II. Therapeutic management and

follow-up. Circulation 2003;108:772–8.

Hagan PG et al: The International Registry of Acute Aortic

Dissection (IRAD): New insights into an old disease. JAMA

2000;283:897–903. [PMID: 10685714]

Karmy-Jones R, Jurkovich GJ: Blunt chest trauma. Curr Probl Surg

2004;41:211–380. [PMID: 15097979]

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

517

CHAPTER 23

518

Leurs LJ et al: Endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic diseases:

Combined experience from the EUROSTAR and United

Kingdom Thoracic Endograft registries. Thoracic Endograft

Registry Collaborators. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:670–9; discussion

679–80. [PMID: 15472593]

Svensson LG, Crawford ES: Aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm

surgery: Clinical observations, experimental investigations, and

statistical analyses. Curr Probl Surg 1992;29:817–911 (part I)

[PMID: 1464240]; 29:913–1057 (part II) [PMID: 1291195];

30:1–163 (part III).

Postoperative Arrhythmias

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Variable heart rate.

Regular or irregular rhythm.

Electrocardiographic abnormalities.

Altered peripheral perfusion.

General Considerations

Significant cardiac dysrhythmias occur in up to one-third of

postoperative cardiac surgical patients. Age is the most con-

sistently identified predictor of postoperative arrhythmias,

although many other risk factors exist, including valvular

disease, cardiomyopathy, ischemia, reperfusion, adequacy of

myocardial protection, metabolic derangements, adrenergic

states, medications, temperature, and mechanical irritants.

Arrhythmias should be classified first by ventricular rate.

The rhythm then is subclassified according to its origin—

supraventricular or ventricular—by establishing the rate of

the atrium and evaluating the status of the atrioventricular

(AV) conduction system. Bradycardias include sinus brady-

cardia, heart block, sinus arrest, and slow junctional

rhythms. Tachycardias include (1) supraventricular arrhyth-

mias (eg, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, premature atrial

contractions, paroxysmal atrial tachycardia, and fast junc-

tional rhythms) and (2) ventricular tachycardia, flutter, fib-

rillation, and premature ventricular contractions.

Conduction defects include heart block, bundle branch

block, and preexcitation. Sometimes, the origin of a rapid

arrhythmia is indeterminate and should be referred to as a

nonspecific wide complex tachycardia.

Etiology

The etiology of perioperative arrhythmias is multifactorial.

Mechanistically, they can be separated into ectopic foci and

reentrant circuits. Both originate either from abnormal car-

diac tissue affected by ischemia, hypertrophy, dilation, car-

diomyopathy, and scar or from normal cardiac tissue

induced by inotropes, endogenous catecholamines, auto-

nomic stimulation, and metabolic derangements.

A. Intrinsic Factors—Age is associated with supraventricu-

lar arrhythmias and heart block in both cardiac and other

thoracic surgical patients. The etiology of this association is

unclear, but the incidence in patients over 65 years of age is

high enough to warrant prophylactic therapy in many cases.

To this end, β-blockers (eg, sotalol) and amiodarone are

commonly used agents. Although routine preoperative pro-

phylaxis against postoperative arrhythmias (particularly

atrial fibrillation) remains controversial, it is increasingly

supported by emerging data. Intrinsic cardiac disease,

including cardiomyopathy, acute coronary insufficiency,

valvular heart disease, congenital lesions, pulmonary hyper-

tension, ventricular outflow obstruction, and ventricular

failure, also increases the incidence and severity of arrhyth-

mias in both the preoperative and postoperative periods.

Cardiomyopathy, both ischemic and nonischemic, as well

as dilated and nondilated, frequently causes both atrial and

ventricular rhythm irregularity and is one of the more com-

mon presenting complaints. Surgical therapy (excluding

aneurysm resection and endocardial ablation) frequently

does not eliminate the cause. Atrial arrhythmias can result

from primary involvement of atrial muscle or secondary

dilation of atrial chambers by ventricular failure. Ectopic foci

and reentrant circuits are the primary underlying causes, but

the metabolic complications of diuresis and inotropes fre-

quently contribute. Ventricular rhythm disturbances develop

by these same mechanisms and are often life-threatening.

Acute coronary arterial insufficiency frequently presents

with severe arrhythmias (particularly ventricular) or heart

block. They can recur or present postoperatively from resid-

ual or recurrent ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Valvular heart disease frequently has residua that predis-

pose to arrhythmias despite correction of the valvular lesion.

The conduction system is anatomically close to valvular

structures and is easily interrupted.

Endocarditis is particularly likely to be associated with

heart block pre- and postoperatively. Aortic disease leads to

left ventricular hypertrophy or ventricular dilatation, both of

which predispose to reentrant circuits or arrhythmic foci.

Mitral and tricuspid valve disease most commonly causes

atrial arrhythmias, primarily fibrillation. These should be

expected to recur with almost 100% certainty in the postop-

erative period.

Congenital lesions frequently are associated with abnor-

malities of the location and function of the conduction sys-

tem and with chamber enlargement or hypertrophy. All these

factors contribute to ectopic foci and reentry. Wolff-

Parkinson-White syndrome is a common congenital lesion

of the conduction system predisposing to reentrant AV

rhythms. Gross anatomic disease is also occasionally associ-

ated with specific rhythm changes. In particular, Ebstein’s

anomaly may be complicated by Wolff-Parkinson-White

syndrome, tetralogy of Fallot is associated with right ventric-

ular arrhythmic foci, and certain types of transposition result

in abnormal conduction anatomy and an increased incidence

of perioperative heart block. Pulmonary and pulmonary

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

519

vascular abnormalities are superimposed on all these lesions

and result in right ventricular enlargement and hypertrophy,

tricuspid regurgitation, and secondary atrial arrhythmias.

B. Extrinsic Factors—Mechanical irritants (eg, chest tubes,

central catheters, blood, and tamponade), metabolic

derangements (eg, hypo- or hypermagnesemia, -kalemia,

-phosphatemia, and -calcemia), adrenergic or vagotonic

states, and cardiovascular drugs are frequent in the postoper-

ative period and can induce and aggravate arrhythmias.

Clinical Features

The approach to the diagnosis of rhythm disturbances in the

postoperative period is similar to that presented elsewhere.

However, because of the unique perioperative factors that

contribute to arrhythmias, an organized, rapid, and complete

evaluation is crucial.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with cardiac arrhyth-

mias in the perioperative period have findings identical to

those seen in nonsurgical patients. They may have more pro-

found and acute circulatory compromise owing to residual

anesthetic agents, cardiopulmonary bypass effects, ongoing

hemorrhage, metabolic derangements, volume shifts,

hypothermia, and residual cardiac disease.

B. Electrocardiography—Unique to cardiac surgical

patients is the frequent presence of ventricular or atrial pac-

ing wires, which can provide valuable information and man-

agement options. Twelve-lead surface electrocardiographic

tracings should be compared with preoperative and earlier

postoperative examinations for evidence of ischemia, rhyth-

micity, conduction abnormalities, QRS-complex and ST-

segment abnormalities, and QT-interval prolongation.

If the rhythm cannot be diagnosed conclusively, an atrial

ECG should be obtained by attaching one or more of the

atrial pacing wires (if not in use for pacing) to the electrocar-

diographic machine or bedside monitor. A predetermined

configuration on the 12-lead machine is usually used, and

the tracings based on the atrial wires will emphasize the atrial

portion of the rhythm despite its small muscle mass.

Signal-averaged ECGs and programmed electrical stimu-

lation are beyond the scope of this text but should be pur-

sued on an individual basis to establish a diagnosis, stratify

risk, and evaluate the effects of treatment.

C. Laboratory Findings—Arterial blood gases and elec-

trolytes should be obtained to exclude acidosis, alkalosis, and

electrolyte abnormalities. Serum potassium and calcium lev-

els merit particular attention.

Invasive Hemodynamic Monitoring

Invasive hemodynamic monitoring with arterial lines and

flow-directed pulmonary artery catheters typically is per-

formed to assist with management after cardiac surgery.

Analysis of these data is invaluable in the diagnosis and man-

agement of postoperative arrhythmias. Furthermore,

confirmation of appropriate waveforms (eg, pulmonary cap-

illary wedge pressure and pulmonary artery pressure) with

the pulmonary artery catheter may decrease the suspicion of

mechanical irritation from the catheter, significantly con-

tributing to the arrhythmias.

Differential Diagnosis

Problems peculiar to postoperative cardiac surgical patients

that may lead to arrhythmias include hypovolemia, bleeding,

pericardial tamponade, tension pneumothorax, thrombosis

or dehiscence of a prosthetic valve, coronary ischemia, and

hypoxia. Care must be exerted to ensure that the bedside

monitor is working correctly and that observed rhythms are

not due to electrical interference.

Treatment

A. Antiarrhythmics—Arrhythmias are frequent postopera-

tively, and prophylaxis with a variety of agents appears effec-

tive. In particular, β-blockers reduce the incidence and

severity of atrial arrhythmias and probably prevent some

ventricular arrhythmias. Although there is conflicting evi-

dence, magnesium appears to have some antiarrhythmic

effects and may reduce the incidence of atrial fibrillation,

atrial flutter, and ventricular arrhythmias as well. Calcium

channel blockers may have similar benefits, but these agents

are less well studied in the postoperative context.

Amiodorone, a class III agent, has been shown recently, albeit

in a very small study, to reduce the incidence of postopera-

tive arrhythmias when administered perioperatively. Further

discussion of the medical treatment of arrhythmias is found

in detail in Chapter 22.

B. Cardioversion—In addition to pharmacologic measures,

preparation should be made for rapid cardioversion in

patients at high risk for severe ventricular arrhythmias.

Patients who have had ventricular fibrillation perioperatively

may require immediate cardioversion. Equipment should be

ready at the bedside and attached to the patient. Much of the

morbidity of severe ventricular arrhythmias can be avoided

by immediate cardioversion.

The rhythm type and chamber of origin—atrial, junc-

tional, or ventricular—should be established. If the atrial

arrhythmia is fast and poorly tolerated (ie, symptomatic),

immediate electrical conversion is warranted. To convert

atrial fibrillation or flutter, high-energy shock usually is

required and always should be synchronized. Overdrive atrial

pacing may be performed at the bedside using the atrial epi-

cardial pacing wires. This is most effective for supraventricu-

lar tachyarrhythmias such as atrial flutter and paroxysmal

atrial or AV junctional reentrant circuits. Rapid atrial pacing

also can interrupt a reentrant circuit such as atrial fibrilla-

tion, thereby restoring sinus rhythm, although less effec-

tively. When performing overdrive pacing, great vigilance

must be exercised to ensure that the atrial leads—rather than

the ventricular leads—are attached to the generator.

CHAPTER 23

520

Ventricular tachycardia frequently can be terminated

with low-energy synchronized cardioversion. Ventricular fib-

rillation should be treated immediately with high-energy

defibrillation, usually unsynchronized. Both defibrillation

and cardioversion can worsen the existing rhythm, so one

must be prepared to increase electrical output rapidly and

defibrillate again. If the rhythm is bradycardiac or becomes

so following electrical or chemical conversion, ventricular

pacing should be instituted immediately. After an adequate

heart rate is obtained with ventricular pacing, the patient can

be converted to atrial or AV sequential pacing if wires are

available. If wires are not available or do not function, tem-

porary transvenous pacing (eg, balloon-guided or pacing

pulmonary artery catheter wires) can be attempted.

C. Supportive Measures—If prophylaxis has been unsuc-

cessful, the first objective is to maintain adequate oxygen

delivery and pH control with optimal ventilation.

Circulatory support with cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(CPR) may be necessary while preparations are made for

electrical cardioversion. CPR procedures in cardiac surgery

patients are similar to those followed under other circum-

stances. Closed chest compressions are effective in cardiac

surgery patients and should be used when indicated, as in

any other resuscitation effort. If a pulse is obtained with

CPR, continued efforts at external electrical conversion can

be pursued, but if perfusion is inadequate or external electri-

cal conversion is unsuccessful, open cardiac massage and

internal paddle defibrillation should be considered.

After initial control with electrical conversion in unstable

patients—and primarily in stable patients—the rhythm

should be evaluated for type and probable causes. Many

rhythms are caused by temporary derangements and are best

treated by eliminating the primary cause. Almost all antiar-

rhythmic drugs have adverse side effects even when used

appropriately, and many (perhaps all) are proarrhythmic.

Careful consideration of the risks and benefits of drug ther-

apy is vital because the complications of therapy sometimes

are worse than the underlying arrhythmia. The safest thera-

pies are to optimize electrolytes, decrease sympathetic stim-

ulation, remove mechanical causes, treat ischemia, and allow

some temporary arrhythmias (owing to reperfusion) to

resolve spontaneously with careful monitoring.

Atrial arrhythmias are particularly common and usually

cannot be allowed to persist because they are accompanied by

symptomatic tachycardia. The rate of conduction of atrial fib-

rillation and flutter through the AV node can be blocked with

digoxin, β-blockers, and calcium channel blockers singly or in

combination. After adequate rate control is established, con-

version of the arrhythmia can be accomplished with a class Ia

antiarrhythmic agent (eg, procainamide or quinidine). The

risk of treating relatively benign atrial arrhythmias with class

I agents should be appreciated because there is a chance of

inducing ventricular arrhythmias.

Ventricular arrhythmias in the postoperative period

require individual evaluation of the circumstances, prior

therapy, and risks of drug treatment. Unless a specific cause

is found and removed, most arrhythmias will recur, requir-

ing drug or device therapy to block the effects. For this rea-

son, symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias (eg, tachycardia

or fibrillation) almost always should be corrected.

Kerstein J et al: Giving IV and oral amiodarone perioperatively for

the prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients

undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: The GAP study.

Chest 2004;126:716–24.

Knotzer H et al: Postbypass arrhythmias: Pathophysiology, prevention,

and therapy. Curr Opin Crit Care 2004;10:330–5. [PMID: 15385747]

Mathew JP et al: A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after

cardiac surgery. Investigators of the Ischemia Research and

Education Foundation, Multicenter Study of Perioperative

Ischemia Research Group. JAMA 2004;291:1720–9. [PMID:

15082699]

Palin CA, Kailasam R, Hogue CW Jr: Atrial fibrillation after cardiac

surgery: Pathophysiology and treatment. Semin Cardiothorac

Vasc Anesth 2004;8:175–83. [PMID: 15375479]

Piotrowski AA, Kalus JS: Magnesium for the treatment and pre-

vention of atrial tachyarrhythmias. Pharmacotherapy 2004;24:

879–95. [PMID: 15303452]

Bleeding, Coagulopathy, & Blood

Product Utilization

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Excessive chest tube output.

Hypovolemia.

Bleeding from needle puncture sites.

GI or endotracheal tube bleeding.

Rash, hematuria.

Abdominal or groin distention.

Respiratory compromise.

Neurologic event.

Evidence of tamponade.

General Considerations

Hypocoagulable and hypercoagulable states are known com-

plications of all major surgery but are particularly common

following cardiovascular surgery. Both may adversely affect

outcome. Factors contributing to a hypocoagulable state

include the underlying pathology and anatomy of the heart

or great vessel disease itself and a variety of intrinsic coagu-

lation abnormalities owing to hepatic failure, uremia, drugs,

and cardiopulmonary bypass. Hypercoagulability results

from intravascular stasis, endothelial injury, implanted for-

eign bodies, and derangement of the normal anticoagulant

factors by blood loss, surgical complications, cardiopul-

monary bypass, and drugs.

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

521

Etiology

A number of causes combine to make both bleeding and

excessive coagulation two of the most common complica-

tions of cardiovascular surgery. Both are reviewed here

because of the delicate balance between normal coagulation

and pathologic bleeding or clotting. Factors favoring coagu-

lation and decreased bleeding are complicated by the seque-

lae of excessive thrombosis: myocardial infarction, stroke, or

peripheral embolus.

A. Hypocoagulability—The frequency of blood product

administration varies widely among institutions, but the

incidence of blood and coagulation factor loss in cardiotho-

racic surgery patients is significant at all centers. The major-

ity of coronary, valvular, congenital, and ascending aortic or

arch aortic surgeries performed by current techniques use

total cardiopulmonary bypass and systemic anticoagulation

with heparin, with or without hypothermia. This remains

true even with the recent increased popularity of minimally

invasive techniques (“keyhole” surgery) and “beating heart”

(ie, off-pump) surgery. Descending thoracic aortic surgery is

performed frequently using partial bypass or the “clamp and

sew” technique, both of which eliminate or reduce the need

for anticoagulation with heparin. Total cardiopulmonary

bypass circuits consist of priming solutions, pumps, cannu-

las, tubing, reservoirs, filters, and oxygenators. Each of these

components causes a variety of coagulation changes, includ-

ing dilution of all blood components by priming solution,

consumption and impairment of clotting factors and

platelets by contact with component surfaces, release of

cytokines and complement, blood and factor injury by direct

air contact in the operative field, and injury by turbulence

and mechanical stress. Additionally, many operations use

hypothermia, which further decreases the activity of existing

clotting factors. The length of cardiopulmonary bypass and

the degree of hypothermia employed are related to the sever-

ity of these changes.

In addition to these deleterious changes are the effects

produced by heparin. High-dose heparin (100 units/kg) is

necessary for current bypass circuits to prevent circuit

thrombosis. With the use of heparin-bonded bypass circuits,

lower-dose heparin may be as efficacious, although this is

currently the focus of active investigation. The majority of

heparin’s effects are counteracted by protamine administra-

tion after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass.

Protamine, however, is itself a weak anticoagulant, and the

heparin-protamine complex thus formed impairs platelet

and factor function until cleared from the bloodstream by

the reticuloendothelial system. Occasionally, heparin-

induced antibodies or protamine intolerance complicates the

perioperative course and requires specific therapy as out-

lined below. The development of bypass circuits with

improved biocompatibility (eg, heparin-bonded circuits)

may decrease the heparin—and thus the protamine—

requirements. Further, there is ongoing investigation of

heparin alternatives, particularly direct thrombin inhibitors

(eg, bivalirudin), for use in cardiac surgery. Partial bypass

circuits and shunts that do not require an oxygenator (eg, left

atrial to femoral or descending aorta) can be accomplished

with little or no heparin in many instances. This is particu-

larly important in traumatic aortic injuries, where anticoag-

ulation is usually contraindicated.

Numerous risk factors identify patients more likely to

have hemorrhagic complications and require transfusion

therapy. Platelet inhibitors commonly used for treatment

and prevention of cardiovascular disorders include newer

agents such as the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor

inhibitors (eg, abciximab), although aspirin remains the

most commonly used medication. Platelet function is

reduced dramatically by aspirin for up to 10 days following a

single dose. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents have

similar effects but usually are more transient. Heparin ther-

apy preoperatively can result in heparin-antibody-platelet

complexes with subsequent thrombocytopenia or occasional

thrombotic complications. Warfarin therapy preoperatively

typically is reversed by withholding warfarin for several days

until measured coagulation tests are normal. Thrombolytics

usually are combined with both heparin and antiplatelet

therapy and have the additional effect of depleting fibrino-

gen levels. Antibiotics occasionally result in vitamin

K–dependent factor loss. High-dose penicillin-like antibi-

otics can cause profound platelet dysfunction.

A number of systemic diseases cause specific defects.

Uremia primarily affects platelet function, and hepatic failure

(primary or secondary to alcohol or congestive heart failure)

results in decreased levels and delayed restoration of clotting

factors. Cyanotic disease is believed to cause factor and

platelet dysfunction. Thrombocytopenia and factor defi-

ciency frequently occur with septicemia associated with endo-

carditis. Von Willebrand’s disease and other inherited platelet

and factor abnormalities usually can be identified by a careful

preoperative history. Poor tissues are associated with malnu-

trition, age, organ failure, advanced endocarditis, and connec-

tive tissue disease. Transfusion reactions are sometimes

difficult to detect but can cause severe coagulopathies.

Reoperations and procedures requiring multiple suture

lines, work on abnormal tissue, and extensive operative dis-

sections increase the risk for bleeding. These include all reop-

erations, aortic dissections and aneurysms, multiple-valve

and combined procedures, complex congenital heart disease,

and patients who require ventricular support.

Prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass, hypothermia, circu-

latory arrest, a history of massive intraoperative blood loss,

and perioperative cardiovascular collapse all decrease the

level and function of platelets and clotting factors. A history

of heparin resistance or a protamine reaction frequently her-

alds a fibrinolytic state, intravascular coagulation, or severe

platelet or factor deficiency.

Recent efforts to modify the bypass circuit with heparin

bonding or to improve surgical techniques (eg, by minimally

invasive or “beating heart” surgery) appear to ameliorate the

inflammation and coagulation abnormalities after cardiac

CHAPTER 23

522

surgery. However, even with these advances, current tech-

niques are only partially effective; thus coagulation abnor-

malities continue to be a major cause of morbidity after

cardiac surgery.

B. Hypercoagulable States—Hypercoagulable states are

classically explained by Virchow’s triad of stasis, endothelial

injury, and systemic hypercoagulability. Stasis is present dur-

ing low-flow states, periods of immobility, during certain

arrhythmias, and intraoperatively during vessel or chamber

cannulation or clamping. The risk of major arterial thrombo-

sis and deep venous thrombosis appears to be low in patients

who have undergone full anticoagulation. In procedures such

as descending aortic replacement with heparinless shunts or

without bypass, the risk is similar to that of other thoraco-

tomy and vascular surgery patients. Endothelial injury (ie,

abnormal endothelium) is ubiquitous in cardiovascular sur-

gery and includes coronary anastomotic sites, vascular clamp

sites, tears in aortic dissection patients, conduits, valves,

intravascular or cardiac patches, and numerous arterial and

venous catheters. Systemic hypercoagulability occurs after all

types of major surgery presumably owing to coagulation fac-

tor activation and derangements of factor levels. Naturally

occurring anticoagulants, including proteins A, C, and S and

antithrombin III, are also frequently depleted, particularly in

patients receiving heparin, warfarin, or thrombolytics. In

addition to coagulation abnormalities caused by the disease

process and its treatment, both inherited and acquired hyper-

coagulable states (eg, activated protein C resistance), which

are being recognized increasingly, also may coexist and con-

tribute to a perioperative hypercoagulable state.

Hypercoagulability is less common than hypocoagulabil-

ity but has dramatic consequences. Liver disease, either pri-

mary or secondary (eg, congestive hepatopathy), also may

result in anticoagulant factor depletion. Antifibrinolytics (eg,

aprotinin) and desmopressin can result in a hypercoagulable

state, and their use should be evaluated critically. Heparin-

induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is an increasingly recog-

nized phenomenon in cardiac surgery and may be a

significant contributor to associated morbidity and mortal-

ity. HIT can result in thromboembolic complications with

significant associated morbidity and mortality. Patients with

prior deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or

thrombophlebitis are especially prone to recurrent thrombo-

sis, and early anticoagulation should be considered. Patients

undergoing coronary endarterectomy appear to have an

increased risk of graft thrombosis and usually are started on

antiplatelet agents immediately after surgery. Areas of stasis

are always at risk for thrombosis. These include the deep

veins in immobile patients and the left atrium in those with

atrial fibrillation or akinetic endocardium after a myocardial

infarction. The presence of intravascular foreign bodies may

increase the risk of thrombosis. Catheters, patches, valves,

conduits, balloon pumps, and ventricular assist devices may

cause thrombosis and embolism.

In summary, hemostatic and coagulation abnormalities

are very common in cardiac surgical patients and clearly

contribute to associated morbidity and mortality. The etiol-

ogy often is complicated, involving myriad interrelating fac-

tors. Nonetheless, appreciation of these causative factors is

important to optimize care of the cardiac surgical patient.

Clinical Features

A. Chest Tube Output—Chest tube output varies widely

among patients and over time in individuals. It should be

considered in the context of chest x-ray findings, hemody-

namics, previous outputs, surgical findings, and the patient’s

history. Chest tube output is frequently miscalculated as a

result of autotransfusion, multiple tubes and containers, and

in unrecorded intervals such as during patient transport.

These possible errors should be considered, and a repro-

ducible technique of recording and reporting outputs should

be established. Many valid definitions of excessive chest tube

output exist; in the descriptions that follow, output greater

than 200 mL/h for 2 hours is considered significant, whereas

output greater than 400 mL/h for 2 hours is considered

severe. Chest tube output during the first 2 hours following

operation is extremely variable owing to retained blood in

the pleural space and lack of drainage during transport.

Increased drainage can be expected during this period.

Greater than 200 mL/h of drainage after the initial period

may indicate the need for reexploration. The average chest

tube output over 24 hours is approximately 1200 mL in pri-

mary low-risk coronary artery bypass graft patients, but it

may be significantly higher after more complex procedures.

If chest tubes are clotted or do not communicate with the

bleeding site, cardiovascular instability consistent with hypo-

volemia frequently will be the presenting sign. Inadequate

resuscitation of prior or ongoing severe bleeding presents in

a similar fashion.

Patients with excessive drainage from chest tubes

should be thoroughly examined for diffuse oozing from

other sites such as needle punctures, wounds, and nasogas-

tric tubes. A generalized rash and hematuria should alert

one to the possibility of hemolysis owing to a transfusion

reaction. Other findings suggestive of bleeding include

abdominal or groin distention, respiratory compromise

owing to intrapleural blood, low cardiac output owing to

tamponade, and neurologic changes from hypoperfusion

or intracranial hemorrhage.

B. Thrombosis—An uncommon result of a relative hyperco-

agulable state is prosthetic valve thrombosis. Although most

common in patients not adequately anticoagulated chroni-

cally, valve thrombosis can occur at any time in the hospital

course and requires immediate diagnosis. A new murmur

suggesting outflow or inflow obstruction or valvular insuffi-

ciency should be investigated immediately with echocardio-

graphy. Hemodynamic changes may be severe.

Arterial occlusions owing to primary thrombosis or sec-

ondary to embolus may be subtle or dramatic and are quite

common. The arteries at highest risk for primary thrombosis

are recent coronary or peripheral grafts, peripheral cannula-

tion sites, and arteries with preexisting stenosis. An arterial

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

523

embolus will have a similar presentation, but multiple emboli

commonly occur with combined neurologic, coronary, GI,

and peripheral findings. Subtle neurologic changes are sensi-

tive indicators of arterial thrombi or emboli. Findings associ-

ated with arterial occlusion under normal circumstances may

be blurred by perioperative low-flow states, systemic

hypothermia, and preexisting arterial disease.

Venous thrombosis or venous embolism (ie, pulmonary

embolism) is not seen commonly following cardiac surgery

presumably because of systemic anticoagulation during car-

diopulmonary bypass. Since lower extremity edema follow-

ing cardiac surgery is common, owing to increased

extravascular water and venectomy incisions, lower extrem-

ity venous duplex ultrasound examination is critical for diag-

nosis when deep venous thrombosis is suspected. In

congenital disease, systemic and pulmonary venous patches

and conduits are potential sites for thrombosis.

C. Imaging Studies—The routine postoperative chest x-ray

should be reviewed in any patient with suspected bleeding.

Changes in mediastinal width (corrected for technique),

pleural accumulations, and other lesions causing hemody-

namic compromise can be diagnosed rapidly.

D. Laboratory Findings—Activated clotting times (ACTs)

are obtained routinely to determine the adequacy of antico-

agulation during bypass and to assess its reversal by prota-

mine. A normal ACT is between 100 and 120 seconds.

Anticoagulation during bypass increases it to over 400 seconds.

Limited anticoagulation usually falls in the range of

150–250 seconds.

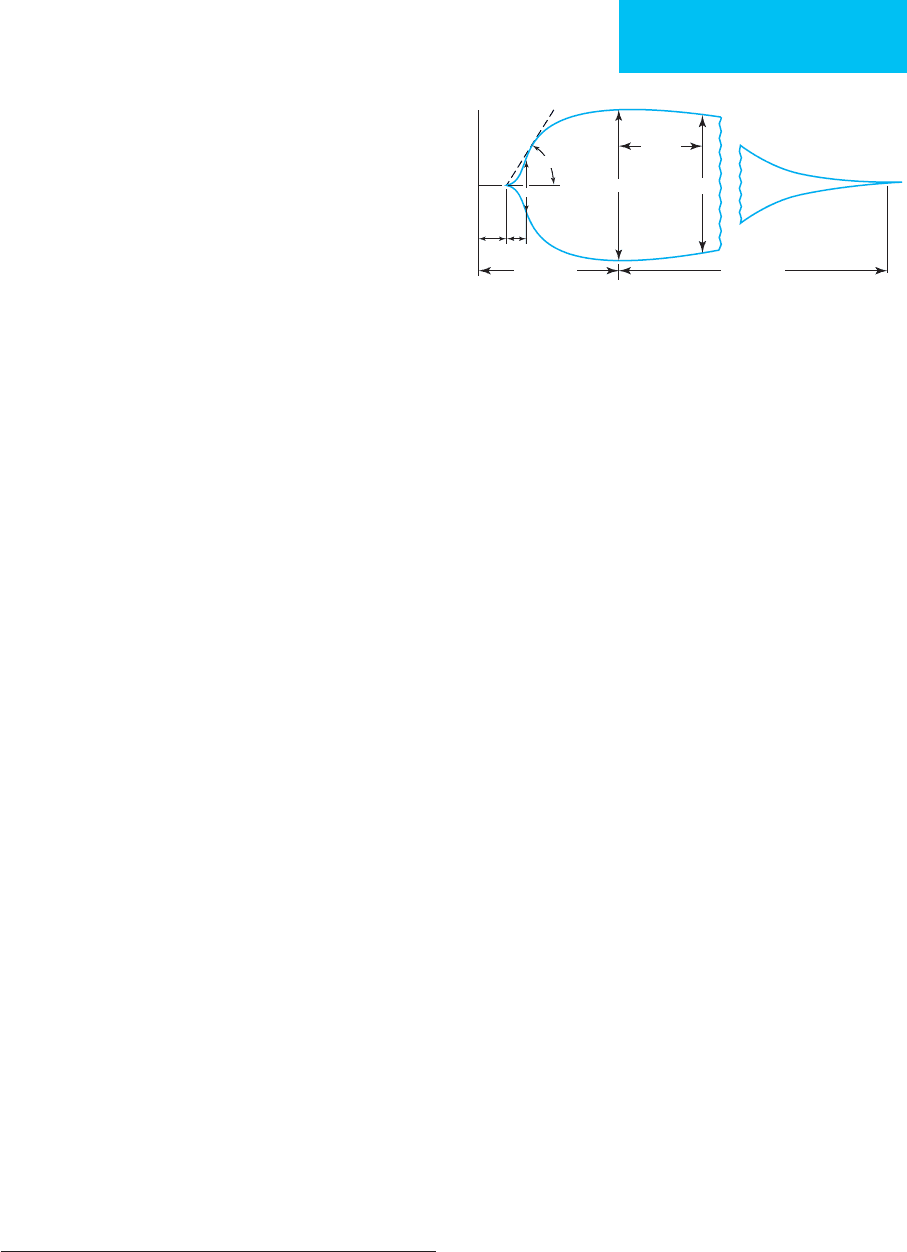

Thromboelastography gives a rapid assessment of the

adequacy of the coagulation cascade and can help to predict

the subgroup of patients whose bleeding is due to an under-

lying disorder. Thromboelastography also can identify

unsuspected hypercoagulable patients. Five parameters are

measured (Figure 23–2). The specific cause of an abnormal

thromboelastogram can be further investigated by routine

coagulation tests (described below).

Platelet counts should be obtained in patients with long

or complex bypass runs and those with excessive bleeding.

However, platelet dysfunction is common perioperatively

despite adequate platelet numbers and is probably the most

common cause of excessive bleeding. Unfortunately, no sim-

ple reproducible test of in vivo platelet function is currently

available. Template bleeding time can provide some infor-

mation but is not recommended on a routine basis. It

should be obtained in patients with a history of bleeding or

refractory postoperative blood loss. A very prolonged tem-

plate bleeding time (>8 minutes) is suggestive of significant

platelet dysfunction.

Routine coagulation tests—international normalized

ratio (INR),

∗

partial thromboplastin time (PTT), thrombin

time (TT), fibrinogen level, and fibrinogen degradation

products (FDPs)—should be obtained in any patient with

severe bleeding who will be receiving factor replacement. The

INR is frequently mildly elevated early postoperatively in all

patients, but an INR greater than 1.7 in a patient with exces-

sive bleeding should be corrected. TT is extremely sensitive

to the presence of heparin, whereas PTT accurately reflects

the level of heparin activity. Fibrinogen deficiency and elevated

FDPs usually indicate excessive fibrinolysis consistent with

consumption coagulopathy. Using the preceding guidelines,

MA

A

60

60 min

FibrinolysisThrombosis

ρ

K

20 mm

α°

Figure 23–2. Quantification of thrombelastograph vari-

ables: r = reaction time (time from sample placement in

the curette until thrombelastograph tracing amplitude

reaches 2 mm [normal range 6–8 min]). This represents

the rate of initial fibrin formation and is related function-

ally to plasma clotting factor and circulating inhibitor

activity (intrinsic coagulation). Prolongation of the r time

may be a result of coagulation factor deficiencies, antico-

agulation (heparin), or severe hypofibrinogenemia.

A small r value may be present in hypercoagulability syn-

dromes. K = clot formation time (normal range 3–6 min),

measured from r time to the point where the amplitude

of the tracing reaches 20 mm. The coagulation time rep-

resents the time taken for a fixed degree of viscoelastic-

ity to be achieved by the forming clot as a result of fibrin

buildup and cross-linking. It is affected by the activity of

the intrinsic clotting factors, fibrinogen, and platelets.

Alpha angle (α°; normal range 50–60°) = angle formed

by the slope of the thrombelastograph tracing from the

r to the K value. It denotes the speed at which solid clot

forms. Decreased values may occur with hypofibrinogene-

mia and thrombocytopenia. Maximum amplitude

(MA; normal range 50–60 mm) = greatest amplitude on

the thrombelastograph trace and is a reflection of the

absolute strength of the fibrin clot. It is a direct function

of the maximum dynamic properties of fibrin and

platelets. Platelet abnormalities, whether qualitative or

quantitative, substantially disturb the MA. A

80

(normal

range = MA – 5 min) = amplitude of the tracing 60 min-

utes after MA is achieved. It is a measure of clot lysis or

retraction. The clot lysis index (CLI; normal range >85%)

is derived as A

80

/MA × 100 (%). It measures the ampli-

tude as a function of time and reflects loss of clot

integrity as a result of lysis. (Reprinted, with permission,

from Mallett SV, Cox DJA: Thromboelastography. Br J

Anaesth 1992;69:307–13.)

∗

The INR is the equivalent of the prothrombin time (PT) corrected

for the wide interlaboratory variation in reagents and PT results.

CHAPTER 23

524

the results of routine coagulation tests are used to direct

therapy at the specific defects outlined below.

To monitor the proper perioperative anticoagulation in

patients with artificial valves and other indications for sys-

temic anticoagulation, the INR is obtained on a daily basis

before and after beginning warfarin therapy. The INR is

superior to the PT because it minimizes interlaboratory

reagent variation. Appropriate levels for given circumstances

are outlined below. In occasional patients at high risk for

thrombosis or those who may need further invasive proce-

dures postoperatively, heparin is started when deemed safe,

and anticoagulation is maintained at a level appropriate for

the relative risks using PTT assays or the ACT. When HIT is

suspected based on clinicopathologic findings, antibodies to

heparin–platelet factor 4 complex should be sought (ie, HIT

antibody test), and heparin administration is stopped

immediately.

Differential Diagnosis

Bleeding is usually easy to diagnose while chest tubes are in

place if they are not clotted and if they communicate with the

bleeding site. If the patient is hypothermic on arrival to the

ICU owing to surgical techniques, then core rewarming over

the first 1–2 hours can be associated with progressive vasodi-

lation, hemodynamic changes, and a fluid requirement that

can be mistaken for ongoing bleeding. Pleural accumulations

of blood or serous fluid are common, and their drainage can

be alarming but benign, as can mediastinal collections.

Hemolysis is rarely confused with significant bleeding but

should be considered. Intrinsic cardiac dysfunction and con-

gestive heart failure may present with hypotension, hemodi-

lution, and congestion similar to hypovolemia or tamponade,

as can any other cause of shock and hypotension.

Arterial thromboembolic complications easily can be

confused with poor perfusion owing to low-output states

and vasoactive drugs. Vascular spasm is particularly common

with mammary artery grafts and can mimic occlusion.

Spasm of peripheral vessels may be observed. Cholesterol

emboli from an atherosclerotic aortic wall are probably

much more common than thromboemboli owing to dissem-

inated clotting. Cholesterol emboli usually present immedi-

ately postoperatively and are frequently multiple.

Treatment

A. Bleeding—If postoperative bleeding is apparent, one

must immediately ensure the availability of adequate sup-

plies of blood products. Careful fluid balances are crucial and

should be reported in a reproducible fashion at appropriate

intervals. Patients should be rapidly stratified according to

the level of bleeding. Bleeding less than 200 mL/h frequently

stops without additional therapy as the effects of cardiopul-

monary bypass and anticoagulation resolve. Bleeding greater

than 300 mL/h only rarely resolves spontaneously. Severe

bleeding (>400 mL/h) frequently requires operation. If the

patient is hemodynamically stable, evaluation for a nonsurgical

cause of bleeding may be undertaken provided that prepara-

tion for mediastinal exploration is begun and sufficient

blood products are available.

If patients can be stabilized and bleeding is less than mas-

sive, a check for residual heparin can be performed with an

ACT in a few minutes. Protamine then should be adminis-

tered if the ACT is elevated above baseline. A platelet count

should be checked, although an adequate number does not

equate with adequate function. Thromboelastography can

provide an overview of the level of coagulation, and if it is

normal, one should suspect a surgical cause for the bleeding.

Routine coagulation tests can be obtained to guide specific

factor therapy and to rule out ongoing fibrinolysis.

B. Transfusion—Transfusion therapy is guided by the

hemostatic laboratory profile, which should be easily and

rapidly obtained. Usually, platelets are the initial therapy

because they augment platelet function, supply fresh-

frozen plasma, and provide a source of fibrinogen with the

same number of donor exposures. If platelet concentrate

fails to correct the deficit or severe factor deficiencies are

documented, an elevated INR is usually treated with fresh-

frozen plasma, and a diminished fibrinogen is treated with

cryoprecipitate.

C. Other Agents—Antifibrinolytics such as aminocaproic

acid (4–5 g in 250 mL of diluent over 1 hour intravenously,

followed by 1 g/h as a continuous infusion) can be added if

fibrinolysis is significant; however, most agents should be

given preoperatively for full effect. Patients felt to be at high

risk for bleeding should be treated prophylactically.

Desmopressin acetate (0.3 μg/kg intravenously over 15–30

minutes) is particularly effective in the treatment of patients

with platelet deficiency owing to uremia or von Willebrand’s

disease, but it may cause increased graft thrombosis.

Conjugated estrogens and serine protease inhibitors also may

be helpful in treatment of uremic bleeding, although consid-

eration always must be given to the risks and benefits of these

pharmacologic therapies. Recently, recombinant factor V11a

has become available to assist with hemorrhagic complica-

tions following cardiac surgery. Although it has been used

with success in both the adult and the pediatric population,

an evidence-based approach guiding its use is not yet avail-

able. Similar to published reports, we have found it useful in

the setting of continuing hemorrhage and coagulopathy

despite ongoing transfusion of usual products in the absence

of surgical bleeding.

If correction of the clotting mechanism does not stop the

hemorrhage, immediate surgical exploration is mandatory

irrespective of the patient’s hemodynamic status.

D. Thrombosis—Clinical (eg, chest pain and hemodynamic

changes) and electrocardiographic (eg, ST-segment changes)

evidence for coronary graft thrombosis is not infrequently

due to graft spasm, particularly with arterial conduits (mam-

mary arteries). In unresolved cases, echocardiography should

be obtained to evaluate wall motion in the suspect arterial

CARDIOTHORACIC SURGERY

525

territory. Antispasmodics should be instituted (eg, calcium

channel blocking agents, nitroglycerin, or phosphodiesterase

inhibitors) while diagnostic evaluation continues. Many cen-

ters give antispasmodics (eg, calcium channel blockers) pro-

phylactically in an attempt to avoid spasm. If wall motion

abnormalities are documented and persist with antispas-

modics, angiography may be indicated to confirm graft

patency. Reexploration of grafts then is considered on an

individual basis.

Peripheral thromboembolism is not uncommon in open-

heart surgery and occurs in the presence of a left ventricular

thrombus, preexisting vascular disease, and injuries from

prior angiography. Additionally, peripheral emboli and

thrombosis are frequent in patients with intravascular pros-

theses or devices, particularly intraaortic balloon pumps and

prosthetic valves. All unnecessary foreign bodies should be

removed as soon as possible. Patients should be stratified

according to risk of thrombosis, and those who subsequently

have a thromboembolism despite one level of anticoagulation

should be increased to the next level of anticoagulation, and a

thorough evaluation of why they failed should be undertaken.

Patients with a high risk of thrombosis, delayed onset of long-

acting anticoagulants (eg, warfarin), or evidence of current

thromboembolism should be treated with rapid-onset anti-

coagulants (eg, heparin) with appropriate consideration of

the risk of bleeding in the perioperative period.

All patients with unexplained or recurrent thrombotic

episodes should be evaluated for acquired or inherited

thrombophilias, including (at least) resistance to activated

protein C (eg, factor V Leiden or HR

2

haplotype), heterozy-

gosity or homozygosity for factor V Leiden or G20210A

prothrombin mutation, hyperhomocysteinemia, factor VIII

levels, and the presence of lupus anticoagulant. If HIT is

suspected, all heparin should be eliminated. If ongoing

anticoagulation is needed, then direct thrombin inhibitors

or platelet inhibitors can be used until warfarin levels are

adequate. Antithrombin III deficiency can be treated tem-

porarily with fresh-frozen plasma and long term with war-

farin. The treatment of protein A, C, or S deficiency is

approached on an individual basis. Hyperhomocysteinemia

is treated indefinitely with folic acid, supplemented with

vitamins B

6

and B

12

if homocysteine levels do not normal-

ize on folic acid alone.

Doty JR et al: Atheroembolism in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac

Surg 2003;75:1221–6. [PMID: 12683567]

Greinacher A: The use of direct thrombin inhibitors in cardiovas-

cular surgery patients with heparin-induced thrombocytope-

nia. Semin Thromb Hemost 2004;30:315–27. [PMID:

15282654]

Karkouti K et al: Recombinant factor VIIa for intractable blood

loss after cardiac surgery: A propensity score-matched case-

control analysis. Transfusion 2005;45:26–34. [PMID: 15647015]

Levy JH: Pharmacologic preservation of the hemostatic system

during cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:S1814–20.

[PMID: 11722115]

Seligsohn U, Lubetsky A: Genetic susceptibility to venous throm-

bosis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1222–31. [PMID: 11309638]

Warkentin TE, Greinacher A: Heparin-induced thrombocytope-

nia: Recognition, treatment, and prevention. The Seventh ACCP

Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombotic Therapy. Chest

2004;126:S311–37.

Cardiopulmonary Bypass, Hypothermia,

Circulatory Arrest, & Ventricular Assistance

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Decreased peripheral perfusion.

Altered end-organ function.

Hypothermia.

Coagulopathy.

Hemolysis.

Edema, localized or generalized.

General Considerations

More than 30 years ago, the introduction of cardiopul-

monary bypass—and therefore the ability to interrupt and

alter the circulation locally and systemically—revolutionized

the approach to cardiothoracic and other major surgery of

vascular structures. Continued advances in technique have

made cardiopulmonary bypass well tolerated, but untoward

effects still occur, particularly at the extremes of age. Despite

the recent popularity of minimally invasive and off-pump

techniques in cardiac surgery, full cardiopulmonary bypass is

still used for the majority of cardiac surgical procedures in

the United States. An understanding of the pitfalls of car-

diopulmonary bypass are crucial to realizing its benefits.

Both total and partial bypass circuits are used on a rou-

tine basis and are primed with crystalloid, colloid, or blood if

estimated hemodilution will be severe. Total cardiopul-

monary bypass begins with drainage of systemic venous

blood into a reservoir via a venous cannula. A separate

pump-driven cardiotomy suction device can be added to

return shed blood from the operative field to the same reser-

voir. Blood then is actively pumped through an

oxygenator/heat exchanger and back to the systemic circula-

tion via the arterial cannula. A number of additional special-

ized circuits deliver cardioplegia, provide pulmonary venous

and collateral drainage (vents), or perfuse localized areas.

Arterial and venous cannulas are usually placed in the

ascending aorta and right atrium, but a number of locations

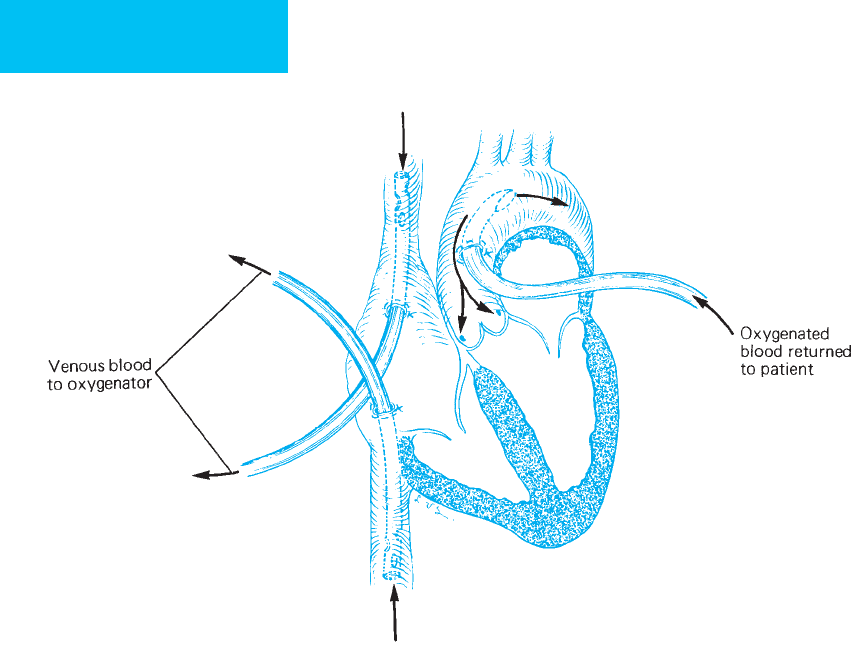

are used on an individual basis (Figure 23–3). Partial bypass

circuits include venovenous bypass (usually with oxygenator),

left atrioarterial or right atriopulmonary bypass or ventric-

ular assist (usually without oxygenator), and simple arte-

rioarterial and venovenous shunts, with or without pumps

CHAPTER 23

526

or oxygenators. Severe adverse effects of cardiopulmonary

bypass strictly owing to the circuit itself are rare but include

massive air embolism, aortic dissection from cannulas or

clamps, general or localized venous congestion from kinked

or misplaced return lines; severe hypoxia from oxygenator

dysfunction; and a number of unusual but significant events.

One or more lesser effects of the cardiopulmonary bypass cir-

cuit are nearly universal. Microscopic air, platelet, and cho-

lesterol emboli; direct blood cell trauma; and endothelial

injury may occur secondary to mechanical pump or cannu-

lation injury.

Blood contact with the artificial surfaces of the circuit

causes a variety of undesirable effects, including systemic

inflammation (ie, elaboration of cytokines and leukocyte

activation), complement activation, coagulation abnormali-

ties, and endothelial cell activation. Indeed, these changes

contribute to the morbidity and mortality of cardiac sur-

gery. Full anticoagulation with heparin (300 units/kg) is

required in all circuits to prevent widespread coagulation,

although lower anticoagulation protocols may prove equally

efficacious as the biocompatibility of the circuits improves

(ie, heparin bonding). Partial-bypass circuits—and some

full-bypass circuits with heparin-bonded components—

frequently can be maintained with little or no systemic anti-

coagulation depending on flow, component surfaces, and

the effects of the pump, filters, and special devices. Circuit

priming solutions and added fluids cause hemodilution,

which is frequently helpful in diminishing blood cell loss

but may be excessive in patients with low blood volumes. In

selected patients with generous prebypass blood cell vol-

umes, whole blood or blood components may be removed

prior to bypass for retransfusion postoperatively. This

restores coagulation factor activity and reduces homologous

blood product utilization.

Perfusion during total cardiopulmonary bypass is almost

always nonpulsatile, and flow is maintained at a level to

ensure adequate end-organ perfusion based on metabolic

demands. Perfusion during partial bypass or ventricular sup-

port may be pulsatile or nonpulsatile depending on the cir-

cuit and device. Flows in these local circuits are determined

by arterial resistances in the native perfused and mechani-

cally perfused beds, left- and right-sided pressures during

ventricular support, inflow limitations, technical considera-

tions, and device capabilities. Measured pump flows are

felt to be more crucial than blood pressure in patients

without vascular stenoses. Typical flows at normothermia

Figure 23–3. Cannulation sites used commonly in connecting the extracorporeal circuit. Venous blood is drained

through tubes introduced into both venae cavae. Oxygenated blood is returned to the arterial system through a tube in

the aorta. (Reproduced, with permission, from Way LW (ed), Current Surgical Diagnosis & Treatment, 10th ed. Originally

published by Appleton & Lange. Copyright © 1991 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)