Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

■

SCYTHIANS

The Scythians (Assyrian: “Asˇguzai” or “Isˇguzai”;

Hebrew: “Askenaz”; Greek: “Scythioi”) were a no-

madic people belonging to the North Iranian lan-

guage group. Their earliest mention, by Assyrian

sources, comes from the first half of the seventh cen-

tury

B.C., during the reign of Esarhaddon (681–669

B.C.). The Scythians then appeared in northern

Media, in the Lake Urmia region of Mannea (in

modern-day Iran). They were involved in the Medi-

an-Assyrian conflicts. As Assyrian allies, in 673

B.C.

they helped to suppress a Median uprising under the

leadership of Kasˇtaritu. They played a still more im-

portant role in 653

B.C., saving the Assyrian capital

of Nineveh, besieged by Kasˇtaritu’s army.

At that time the Scythians were a significant mil-

itary power. Their raiding parties ventured as far as

the borders of Egypt in Syria, even forcing the pha-

raoh Psamtik I (r. 663–609

B.C.) to pay them ran-

som. In about 637

B.C., during the reign of Ashur-

banipal (669–631?

B.C.), they played an important

role in defeating the Cimmerians, dreaded invaders

that wreaked havoc across Asia Minor. Earlier still,

the Scythians forced the Cimmerians out from the

lands north of the Caucasus and the Black Sea. It

was Cyaxares (r. 625–585

B.C.), the ruler of Medes,

who finally managed to drive the Scythians out of

the Near East.

ORIGIN OF THE SCYTHIANS

The most important accounts on the origins of the

Scythians can be found in the Histories of Herodo-

tus (book 4) relating to “the Scythian-Cimmerian

conflict.” According to this Greek historian, the

Scythians, as a migrating people, invaded and con-

quered the lands north of the Black Sea, forcing out

the indigenous Cimmerians. Herodotus locates

their original dwelling sites somewhere in Asia. He

writes: “The Scythians were a nomadic people living

in Asia. Oppressed by the warlike Massagetae [an-

other nomadic central Asian people], they crossed

the Araxes River [the Volga] and penetrated into

the land of the Cimmerians [who were the original

inhabitants of today’s Scythian lands].”

In the absence of historical data, archaeology

has played the main role in determining the Scythi-

ans’ original “Asian” settlements. During the last

quarter of the twentieth century, exploration

showed that the origins of Scythian culture should

be sought mainly in central Asia, in the upper

Yenissei River basin, the Altai hills, and the steppes

of eastern Kazakhstan. As early as the ninth century

B.C. the Scythians’ nomadic ancestors began to mi-

grate westward from those territories, along a

stretch of the Great Steppe, seeking ecological nich-

es to suit their herding economy. This process also

was stimulated by ecological changes, resulting

from the cold, dry climate prevalent since about the

thirteenth century

B.C. As a consequence, the steppe

pastures degraded. The westward migration gained

impact in the second half of the eighth century

B.C.,

and the mass influx of the Scythian tribes eventually

led to the occupation of the steppes at the foot of

the Caucasus. It was from these regions that the

Isˇguzai launched their Asian invasions.

Beginning in the first half of the seventh century

B.C. the Scythians gradually conquered the middle

regions of the Dnieper River (which had been pene-

trated earlier), on the northern edge of the steppe

in the forest-steppe zone. Despite living in strongly

fortified settlements, the native, settled farming

communities had to yield to the military might of

the invading nomads. Around that time, Scythian

expansion also reached into the Transylvania terri-

tories, located still farther to the west, in the Carpa-

thian valley. With time, especially after withdrawing

from the Near East, the Scythians increasingly fo-

cused their attention on the steppe regions. This

was in part due to climate change and improvement

in the ecological conditions in the steppes north of

the Black Sea. The climate became more humid and

mild, which in Europe manifested itself as the so-

called Subatlantic fluctuation.

Beginning in the mid-seventh century

B.C., the

Black Sea region also became more “attractive” as

the result of the founding of Greek colonies on the

north shores of the Black Sea. The oldest among

them, Borysthenes (also the ancient name for the

river Dnieper), on the island of Berezan at the

mouth of the Boh River, dates from about 646

B.C.

Numerous other colonies, for example, Olbia and

Panticapaeum, soon developed into great economic

(production and trade) centers and played an enor-

mous role in the economic and cultural develop-

ment of the Scythian tribes.

SCYTHIANS

ANCIENT EUROPE

411

After having been driven out from the Near

East in the late seventh century

B.C., the Scythians

shifted their political center to the Black Sea region.

This was not a peaceful process. Its echoes are found

in a legend reported by Herodotus (book 4). The

legend tells of the “old” Scythians returning from

the Near East and fighting with the “young” Scythi-

ans, who were the sons of the slaves and wives of the

“old” Scythians “left behind in the old country.” In

the late seventh and early sixth centuries

B.C. the

military activity of the Scythians was spread over vast

territories, reaching west into the Great Hungarian

Plain and into what is today southwestern Poland.

Gradually, as the result of these processes, Scythian

tribes living in the Black Sea region between the

Don River and the Lower Danube organized them-

selves into a proto-state, called “Scythia” by Herod-

otus. There is no doubt that it consisted of the afflu-

ent ethnic Scythians as well as the conquered local

peoples, in particular, the settled forest-steppe peo-

ples, who were politically and culturally dominated

by the Scythians.

The organization was a sort of a tribal federa-

tion. The power was in the hands of the Scythian

“kings,” local rulers who probably accepted the au-

thority of the leader of the politically strongest tribe.

This complex sociopolitical structure of Scythia

probably is what Herodotus meant when he talked

about the “Royal Scythians” who “consider other

Scythians to be their slaves” and about the “Scythi-

an Nomads,” the “Scythian Farmers,” and the

“Scythian Ploughmen” living in the various regions

of Scythia. Scythia’s political center and, at the same

time, a mythical land, Gerrhus, where the Scythian

kings were buried, was situated in the lower Dnie-

per River basin.

SCYTHIAN ECONOMY

Scythian economy was based on nomadic or semi-

nomadic animal breeding and herding (horses, cat-

tle, and sheep). Wealth, especially in the case of the

Scythian aristocracy, was acquired in wars and pil-

laging raids and through the slave trade with the

Greeks from around the Black Sea. The Scythians

also controlled the trade of grain, which the Greeks

imported from forest-steppe farming regions. From

the Greek colonies the Scythians brought in vast

amounts of wine, transported in amphorae. To the

great astonishment of the Greeks, the Scythians

drank it without water. Also highly valued were

Greek pottery, metal libation vessels sometimes

made from precious metals, rich ornaments, and

jewelry—often true masterpieces of Greek crafts-

manship.

SCYTHIAN CULTURE

Between nomadic “barbarian” civilization and the

north Black Sea variant of Greek civilization, certain

syncretic cultural phenomena confirm the close co-

existence of the two elements. This is evidenced in

a specific Greco-Scythian decoration style of metal-

lic objects, vessels, ornaments, and weaponry items

produced for the Scythians in Greek workshops.

This style combines zoomorphic features character-

istic of the Scythian world of cult and magic with

mythological scenes and narration describing the

life of common mortals, presented in typical situa-

tions and settings. Many of the masterpieces, for ex-

ample, a famous cup from the Kul’-Oba kurgan, or

a gold pectoral found in Tovsta Mohyla, and a gold

comb from the Solokha kurgan, are excellent icono-

graphic sources that shed light on Scythian ways,

behavior, and appearance.

The unity of the Scythian cultural tradition is

symbolized by a characteristic “triad,” consisting of

a common decoration style dominated by zoomor-

phic motifs; the manner of restraining horses, re-

flected in a homogenous bridle set, and, above all,

original weaponry—predominantly bows and ar-

rows. The Scythians’ use of a hard composite (re-

flex) bow with a long range and tremendous pierc-

ing power, their excellence on horseback, and their

ability to shoot from any position—at full gallop

without a saddle or stirrups—made the Scythians

fearsome warriors. (This also was the case with other

Great Steppe nomads.) The Scythians employed

distinctive fighting tactics, with warriors arranged in

highly mobile groups, skilled in the use of strata-

gems that exhausted the enemy and that allowed

the Scythians to avoid direct confrontation in unfa-

vorable circumstances. The Scythians were formida-

ble enemies, posing a serious threat even to the con-

temporary world powers. The Assyrians, the Medes,

the Urartes, and later the Perses all had firsthand

knowledge of the might of the Scythians.

Unquestionably, the Scythians gained their

greatest military and political success defeating the

powerful Persian army led by Darius I Hystaspis (r.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

412

ANCIENT EUROPE

521–486 B.C.). Faced with this powerful foe, the

Scythians applied guerrilla tactics, drawing the

enemy far inside the steppe, wiping out smaller regi-

ments, and severing supply lines. Finally, the humil-

iated Darius was forced to withdraw with the devas-

tated remains of his army across the Danube River

into southern Thrace, which was by then a Persian

province. As a result of this victory, the Scythians

were referred to in the ancient tradition as “invinci-

ble.” Some time later, in 496

B.C., Scythian warriors

followed the same route, reaching the Thracian

Chersonesus (or “the Chersonese”) in a military ex-

pedition.

This direction of Scythian politics continued

through the fifth century

B.C., when Scythia entered

into a closer relationship (both peaceful and belli-

cose) with the Thracian state of the Odrisses. It was

centered in present-day southeastern Bulgaria. This

relationship was especially strong (and confirmed by

dynastic colligations) around the mid-fifth century,

during the reign of Sitalkes, who brought the

Odrisses to the peak of their power. Political and

economical stabilization in the Black Sea region in

the fifth and most of the fourth centuries

B.C. fa-

vored Scythian economic polarization. The wealthi-

est “royal” kurgans of the Scythian aristocracy date

from that period. They are the real “steppe pyra-

mids”—burial sanctuaries of Scythian leaders and

rulers. The rulers were buried amid a wealth of fu-

nerary offerings and in the company of servants sac-

rificed especially for the burial. Stone stelae repre-

senting armed men, placed on top of the kurgans,

were the specific apotheosis of a stereotype of a

king-warrior and at the same time of a mythical

ancestor.

THE FALL OF SCYTHIA

In the second half of the fourth century B.C., how-

ever, several factors precipitated a crisis. The devel-

opment of a dry and warm climate, together with

overexploitation of the steppe grazing lands by the

great herds, again triggered migration. As a result

of these changes, from the second half of the fourth

century

B.C., the Sauromates and the Sarmates,

tribes from central Eurasian steppes, began to ven-

ture across the Don River and threaten Scythian ter-

ritories. Simultaneously, a powerful force arose in

southern Europe that eventually changed the

world’s political order—Macedonia. This period

also witnessed the reign of one of the greatest Scyth-

ian rulers, King Ateas (d. 339), an excellent warrior

and experienced leader who supposedly ruled over

all of Scythia. He fought Philip II (r. 359–336), the

king who gave rise to Macedonian power, in a battle

in the Lower Danube in which the Scythians suf-

fered a shattering defeat and the aged king (appar-

ently more than ninety years old) was killed in bat-

tle.

More defeats followed, such as the one suffered

in 313

B.C. at the hands of one of the Diadoches,

the Thracian ruler Lizymachos. The Sarmates mov-

ing in from the east also were an increasing threat.

As a result, during the third century

B.C., Scythian

territories shrank to the area of the Crimea steppes,

where a new political organization appeared with

their capital in the so-called Neapolis Scythica. Dur-

ing the second century

B.C., it still played a certain

political role, fighting for survival with Chersone-

sus, with the Sarmates, and at the end with the Pon-

tic kingdom of Mithridates VI Eupator (r. 120–63

B.C.). Finally, the influx of Sarmatian nomads into

the Crimean region led to the intermixing of both

elements. Remnants of the Scythians survived here

until the third to fourth centuries

A.D., when the

Germanic Goths appeared on the scene. In the af-

termath of the Hun invasion in 375

A.D. the Scythi-

ans disappeared from history.

See also Iron Age Ukraine and European Russia (vol. 2,

part 6); Huns (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Artamonov, Mikhail I. The Splendor of Scythian Art: Trea-

sures from Scythian Tombs. Translated from Russian by

V. R. Kupilyanova. New York: Praeger, 1969.

Davis-Kimball, Jeannine, V. A. Bashilov, and L. T. Yablon-

sky, eds. Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early

Iron Age. Berkeley: Zinat Press, 1995.

Ghirshman, R. Tombe princière de Ziwiyé et le début de l’art

animalier. Paris: Scythe, 1979.

Grjaznov, Michail P. Der Großkurgan von Arzan in Tuva,

Südsibirien. Munich: C. H. Beck, 1984.

Jakobson, Esther. The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetra-

tion of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenic World. New

York: E. J. Brill, 1995.

Jettmar, Karl. Art of the Steppes. New York: Crown, 1967.

L’or des Scythes: Trésors de l’Ermitage. Leningrad: Bruxelles,

1991.

Reeder, Ellen D., ed. Scythian Gold: Treasures from Ancient

Ukraine. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

SCYTHIANS

ANCIENT EUROPE

413

Rolle, Renate, Michael Müller-Wille, and Kurt Schitzel, eds.

Gold der Steppe: Archäologie der Ukraine. Neumünster,

Germany: K. Wachholtz, 1991.

J

AN CHOCHOROWSKI

■

SLAVS AND THE EARLY

SLAV CULTURE

The first certain information about the Slavs dates

to the sixth century

A.D. The question of the loca-

tion, time, and course of ethnogenetic processes

that shaped the “earliest” branch of Indo-

Europeans remains one of the most fiercely dis-

cussed issues in central and eastern European histo-

riography. A modest set of primary written sources

from that period and a larger but more controversial

set of linguistic arguments form the basis of what is

known concerning the beginnings of Slavic history.

It is mostly thanks to archaeological findings that

the understanding of early Slavic culture has broad-

ened in the last fifty years. Authoritative archaeolog-

ical evidence entered into the discussion on the

origins of the Slavs only in the 1960s, when archae-

ologists began to recognize and analyze assem-

blages of artifacts from the fifth through the sixth

centuries throughout the area between the Elbe and

Don Rivers.

According to the “western” thesis, which has

not been analyzed properly with respect to the Pol-

ish territory, the Slavs’ homeland was either in the

basin of the Oder and Vistula (perhaps only the Vis-

tula) or between the Oder and the Dnieper. At pres-

ent, the evidence supporting this hypothesis is weak.

Thorough analysis of the findings from the second

through the fifth centuries from the area of central

Europe, carried out by Kazimierz Godłowski, con-

firmed the nonindigenous character of Slavic cul-

ture on the Oder and Vistula. The fact that the cul-

tural models of two consecutive palaeo-ethnological

phenomena were identical—the archaeological

findings from the second through fifth centuries in

the central and upper Dnieper region and those of

the later Slavic structures from fifth to sixth centu-

ries—was also noted by Godłowski. The reliability

of the “eastern” concept has been constantly grow-

ing, as archaeological source-based research has

progressed in eastern and central Europe. The ar-

chaeologists’ arguments have been confronted with

the contents of historical records.

The Byzantines were the first to notice the

Slavs—raids from a new wave of barbarians from the

north endangered their empire’s Danube border. In

the first half of the sixth century, Jordanes, in his

history of the Goths, pinpointed Slavic settlements

in the region surrounded by the upper Vistula, the

Lower Danube, and the Dnieper. There, according

to Jordanes, along the Carpathian range, “from the

sources of the Vistula over immeasurable area, set-

tled a numerous people of Veneti.” The Veneti were

divided into Sclavenes and Antes—both groups

commonly regarded as Slavs. The Sclavenes lived in

the area from the Vistula to the Lower Danube, and

the Antes inhabited the area to the east of the

Dniester, up to the Dnieper. The Byzantine writer

Procopius of Caesarea, a contemporary of Jordanes,

records in his Gothic War (De bello Gothico) that

“uncountable tribes of the Antes” settled even far-

ther to the east. He recorded that in about

A.D. 512

there was “a considerable area of empty land” to the

west of Sclavenian settlements (perhaps in Silesia?).

It is hard to overestimate the importance of Proco-

pius’s words that Sclavenes and Antes spoke “the

same language” and that they had long had one

common name.

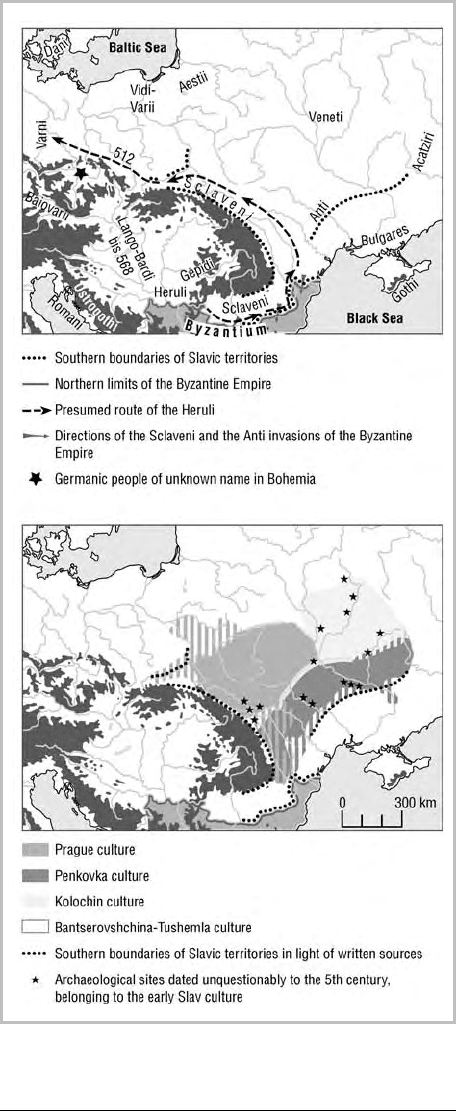

The records of these authors seem to corre-

spond to the area of archaeological phenomena that

is identified with the remnants of the Slavs at the be-

ginning of their great expansion. The southern and

eastern frontier of Slavdom described in the first half

of the sixth century from the Byzantine perspective

matches the border of a specific and exceptionally

homogeneous cultural province, which can be in-

terpreted only as Slavic. All available excavation ma-

terials confirm the division of this province, between

the mid-fifth and mid-seventh centuries, into at

least three tightly interrelated branches. The histori-

cal records allow for the identification of the west-

ern group (the Prague culture) with the Sclavenes

and of the southeastern group (the Penkovka cul-

ture) with the Antes. The name of the third group

(the Kolochin culture) is unknown but was perhaps

the “Veneti.”

These groups represent an identical cultural

model. The differentiation of the discussed archaeo-

logical units is so slight that it is practically based on

a secondary criterion, that is, the differences among

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

414

ANCIENT EUROPE

the characteristic forms of pottery, which is the only

mass finding. The early development stage of all

three cultures (the turn of the sixth century) is char-

acterized by a large majority of simple handmade

pots without ornamentation.

The boundaries of these cultures were trans-

formed considerably in the late sixth century and

into the seventh century. Although the areas occu-

pied by the Kolochin and Penkovka cultures re-

mained the same, the Prague culture spread widely

to the west: it encompassed the basin of the Middle

Danube and the upper and middle Elbe. At the

same time a new phenomenon arose in the basin of

the Oder and on the southern coast of the Baltic

Sea: the Sukow culture, most likely the younger

stage of the Prague culture. Unfortunately, the dis-

appointing state of research on the areas south of

the Danube makes it impossible to obtain a clear

picture of archaeological structures in the Balkans.

The ethnographic characteristics of early Slavic

society captured by historians and archaeologists

allow researchers to describe settlement forms; eco-

nomic structure; the method of artifact manufacture

and its stylistic features; some elements of the social

system, customs, and beliefs; the funeral rite; war-

fare; foreign influences; standards of living; and the

general level of civilization development. Early Slav-

ic settlements hardly ever were found in the moun-

tains: their traces are rarely seen more than 300 me-

ters above sea level. The areas of fertile soil close to

rivers and woods most often were selected. Nonde-

fensive settlements were built along the edges of

river valleys. Typical houses were sunken-floored

huts on a square plan, with sides from 2.5 to 4.5

meters long. The wooden walls were erected in the

form of a log cabin (“blockhouse”) or were of pile

(“Pfostenbaum”) construction. A stone or clay

oven typically stood in one corner, although some

huts had hearths in the center. According to Proco-

pius, the Slavs “live in pitiable huts, few and far be-

tween.” The so-called Pseudo-Maurikios, a Byzan-

tine historian writing at the end of the sixth and the

beginning of the seventh centuries, says, “They live

in the woods, among rivers, swamps and marshes.”

Natural forms of environmental exploitation

pervaded the economy, which was based mainly on

agriculture. The main crops were millet and wheat;

breeding cattle was at the forefront of husbandry

too. As a result, the inhabitants of rural settlements

Location of Slavs in the beginning of sixth century A.D. in light

of written sources (top) and of archaeological data (bottom).

ADAPTED FROM PARCZEWSKI 1993.

were totally self-sufficient, although their lives were

of low standard, a fact noted by the Byzantines. Ac-

cording to Pseudo-Maurikios, the Slavs were nu-

merous and persistent; they easily endured heat,

SLAVS AND THE EARLY SLAV CULTURE

ANCIENT EUROPE

415

chill, and bad weather as well as scarcity of clothes

and livelihood.

No form of well-developed handicraft existed,

apart from a rudimentary form of ironworking. The

models for molten metal ornaments were borrowed

from other cultures, as was the handicraft method

of pottery production with a potter’s wheel (from

the sixth and seventh centuries). There are no clear

traces of widespread trade. Records exist on the

chiefs and tribal elders, who were usually leaders of

small tribes. The funeral rite demanded cremation.

The remains of human bones, with a few rare poor

gifts for the dead, were put in shallow pits, either in

a vessel (an urn) or directly in the soil.

The territory of the later—that is, pre–late fifth

century—Slavic society is unclear. The ethnogenetic

connection between the remains of Slavic settle-

ments from the sixth and seventh centuries and ear-

lier structures can be observed only in the east. The

most reliable archaeological guidelines lead to the

area of the upper and middle basin of the Dnieper,

where a large group of people, whose remains are

defined as “the Kiev culture,” lived from the second

or third century until the beginning of the fifth cen-

tury. This is, as it were, the matrix of the three early

Slavic cultures: the Kolochin culture (taking up al-

most the same area as the Kiev culture earlier); the

Penkovka culture; and, to a large extent, the Prague

culture. In the steppe and forest-steppe zones of the

Ukraine are concentrated the earliest archaeological

assemblages (dated undoubtedly to the fifth centu-

ry) belonging to these three Slavic groups.

The eastern origin of the Slavs is confirmed di-

rectly by one written source. The so-called Cosmo-

graph of Ravenna, writing in the seventh or eighth

century, mentions the motherland of the Scythians,

the place from where generations of Sclavenes origi-

nated. The specific location is unknown but he

mentions the vast area of eastern Europe. The land

inhabited by the Slavs at the beginning of the sixth

century, reconstructed on the basis of archaeologi-

cal findings, was approximately three times bigger

than the area occupied by the Kiev culture in the

first decades of the fifth century. New territories

were taken over in the south and west—up to the

Carpathians, the Lower Danube, and the Upper

and Middle Vistula. The second stage of Slavic terri-

torial expansion took place in the course of the sixth

and seventh centuries. The population masses con-

centrated in the Lower Danube moved to the Bal-

kans and occupied land as far as Peloponnese. A

steppe people of the Avars, who settled in the Car-

pathian Basin in about

A.D. 568, played a significant

role in these events. At the same time other currents

of expansion were moving to the west, reaching the

eastern Alps and the Baltic Sea and occupying the

Elbe basin.

Between the Baltic, the Elbe, and the Danube

the newcomers probably encountered largely empty

territories. In the Balkans, however, they first devas-

tated the area and suppressed the locals and then,

from the end of the sixth century onward, populat-

ed the land inhabited by the Greeks, by the remains

of the Thracians and Germans, and, in the west of

the peninsula, by groups of Romans. One of the

mechanisms of the Slavs’ demographic success—

mass abduction of natives to captivity—is docu-

mented clearly in written records. In time, massive

territorial growth together with the adoption of di-

versified ethnic substrates created the conditions for

a deepening of the divisions in culture (and un-

doubtedly language as well) within what had so far

been a unified Slavic world.

See also Scythians (vol. 2, part 7); Poland (vol. 2, part 7);

Hungary (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baran, V. D., ed. Etnokul’turnaia karta territorii Ukrainskoi

SSR v I tys. n.e. Kiev, Ukraine: Naukova Dumka, 1985.

Barford, Paul M. The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in

Early Medieval Eastern Europe. London: British Muse-

um Press, 2001.

Curta, Florin. The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeol-

ogy of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cam-

bridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

(Note: The opinions of some authors about the localization

of Slavs’ homeland are in fact widely divergent from the

opinions presented in the books of P. M. Barford and

F. Curta.)

Godłowski, Kazimierz. Pierwotne siedziby Słowian. Edited by

M. Parczewski. Kraków, Poland: Instytut Archeologii

Uniwersytetu Jagiellon´skiego, 2000.

———. “Zur Frage der Slawensitze vor der grossen Slawen-

wanderung im 6. Jahrhundert.” In Gli Slavi occidentali

e meridionali nell’alto medioevo, pp. 257–284. Setti-

mane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi Sull’alto

Medioevo 30. Spoleto, Italy: Centro Italiano di Studi

Sull’alto Medioevo, 1983.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

416

ANCIENT EUROPE

———. The Chronology of the Late Roman and Early Migra-

tion Periods in Central Europe. Prace Archeologiczne

11. Kraków, Poland: Uniwersytet Jagiellon´ski, 1970.

Parczewski, Michał. Die Anfänge der frühslawischen Kultur

in Polen. Edited by F. Daim. Veröffentlichungen der

Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Ur- und Frühge-

schichte 17. Vienna: Österreichischen Gesellschaft für

Ur- und Frühgeschichte, 1993.

———. “Origins of Early Slav Culture in Poland.” Antiquity

65 (1991): 676–683.

Popowska-Taborska, Hanna. Wczesne dzieje Słowian w

s´wietle ich je˛zyka. Wrocław, Poland: Ossolineum, 1991.

Sedov, Valentin V. Vostochnye slaviane v VI-XIII vv. Mos-

cow: Nauka, 1982.

M

ICHAŁ PARCZEWSKI

■

VIKINGS

The precise origin of the word “Viking” remains a

mystery. The terms “Viking” and “Viking Age” are

associated with a period of almost three hundred

years, from the late eighth century to the eleventh

century, the last period of the Scandinavian Iron

Age. Although we use the term “Viking” to de-

scribe the land and people of Scandinavia during

that time period, the Northmen or Norse never

used that word to describe themselves, and neither

did neighboring countries. Some scholars think that

the word “Viking” derives from the word vik, the

Scandinavian word for “inlet” or “creek,” but this

interpretation is not universally accepted. Whatever

its origin, the word “Viking” signifies the Scandina-

vian fishing-and-farming people who also under-

took predatory expeditions to fuel their chiefly

economy as well as expand their settlement into new

lands. According to Peter Sawyer in his Kings and

Vikings, “The age of the Vikings began when Scan-

dinavians first attacked western Europe and it ended

when those attacks ceased.”

RAIDS AND EXPANSION

The Vikings conducted raids to exact tribute. Dur-

ing the Dark Ages, it was commonplace within

Scandinavia as well as western Europe and Russia to

plunder neighbors, to exact a tribute from them,

and to secure their submission—to a large extent in-

terchangeable notions. However, it was a new expe-

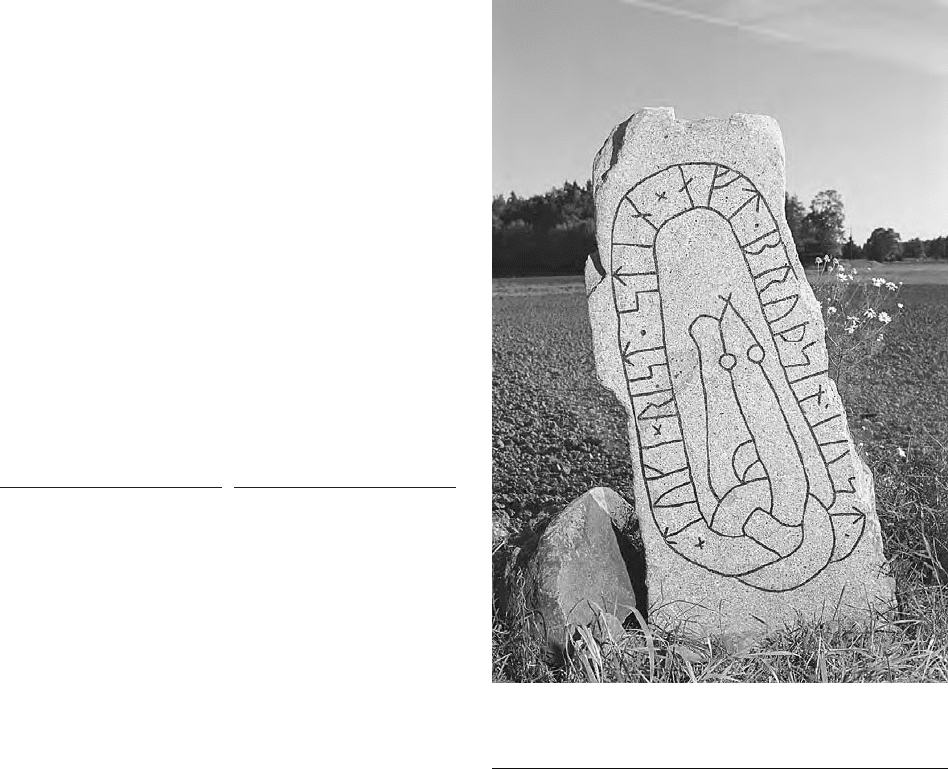

Fig. 1. Rune stone from the Viking period. PHOTOGRAPH BY

BENGT A. LUNDBERG. NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD OF SWEDEN.

REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

rience, and to many a shocking one, when the Scan-

dinavians began to extend their sphere of activity so

far beyond their own borders. The superior skills in

boat making and navigation made this expansion

possible. The topography of the Scandinavian coun-

tries prohibited travel by land; therefore, the water-

ways were their highways. This aided in the devel-

opment of a seafaring culture with extremely

accomplished sailors whose nautical expertise was

their greatest asset in exploiting new lands. The Vi-

kings settled the previously uninhabited island of

Iceland; they developed two settlements in Green-

land, which survived for three hundred years before

mysteriously disappearing; and they arrived in the

New World before Columbus, as seen by archaeo-

logical evidence of their presence in the site of

L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada.

They helped found many cities in Russia, such as

VIKINGS

ANCIENT EUROPE

417

Novgorod, Kiev, and Staraya Ladoga, and artifactu-

al evidence points to trading with a plethora of

places as diverse as Ireland and Byzantium. Their

voyages were diverse in nature; the need for produc-

tive farmland along with the quest for wealth made

the Vikings a mosaic of settlers composed of fight-

ers, traders, and raiders.

DAILY LIFE

The reputation of these Nordic people as fierce war-

riors and raiders has obscured the more complex as-

pects of their everyday life for centuries. The Vi-

kings in their homelands adapted uniquely to an

arctic culture and exploited an extensive array of

available resources. They were fisher-farmers be-

cause the warming effects of the Gulf Stream en-

abled farming much farther north than recorded

previously. They fished the rich waters of the North

Atlantic for the fish of the cod family, halibut, and

wolfish, as well as the local lakes and rivers for fresh-

water fish such as salmon, trout, and char. They har-

vested bird colonies for meat (puffins, guillemots,

and ptarmigan), eggs (duck, seagull, and cormo-

rant), and eider duck down. They also hunted and

scavenged large marine mammals, such as whales

(for meat and oil, and for bone to use for structural

material and for the creation of gaming pieces, fish

net needles, and other implements), and walrus

(primarily for their ivory). Their success as traders

gave rise to a number of trading towns, such

as: Gotland and Birka in Sweden, Hedeby in

Schleswig-Holstein, and Kaupang in Norway.

These towns became the foci of intense commercial

activity and industry, and the goods traded were as

diverse as the people who visited. The artifactual ev-

idence (coins, tools, and ornaments) from excava-

tions in these locations point to connections with

Russia, Europe and North Africa, and shed light on

the transition of Viking life from the farm to the

town, and the beginnings of urbanization and city

formation.

Archaeology has contributed greatly to the un-

derstanding of Viking lifeways. Viking houses were

built with timber, stone, and turf. In this class-

stratified society, large chiefly estates with good pas-

tureland and large boathouses were the homes for

local earls. Inside the houses were central fireplaces

for warmth and cooking. Remains of cauldrons and

steatite vessels, together with other artifacts such as

whetstones for sharpening knives and loom weights

from the upstanding looms that women used to

weave fine woolen clothing, offer glimpses of do-

mestic life. Implements for farming, hunting, and

fishing along with animal bones from middens pro-

vide information on activities involving subsistence

as well as those involving economy and trade. Char-

coal pits, molds, slag, and recovered implements

point to highly skilled craftsmanship in metalwork

while the Viking ships and their surviving wood or-

naments are a stellar example of woodworking. At

Oseberg and Gokstad in southeastern Norway, ex-

cavations of sunken Viking ships undertaken in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth century revealed

beautifully crafted sledges and wagons. Fine gold

jewelry and inlaid silverwork from finds throughout

the Viking world also show a high degree of crafts-

manship. Chess games, horse fights, and wrestling

were all part of Viking daily life, and finds such as

the Lewis chessmen—beautifully carved figurines of

walrus ivory—show the Vikings applying their tal-

ent as artisans to their entertainment as well as their

livelihood.

Military settlements such as Trelleborg in Zea-

land, Nonnebakken at Odense in Fune, Fyrkat near

Hobro, and Agersborg near Limfjorden were all sit-

uated to command important waterways that served

as lines of communication. The layouts of these

camps reflect influences of symmetry and precision

of the Roman castra. The Vikings were organized in

bands called liı, a kind of military household familiar

in western Europe. A chieftain might go abroad

with just his own men in a couple of ships, but more

commonly he would join forces with greater chief-

tains. These were often members of royal or noble

families, styling themselves as kings or earls, and

they frequently seem to have been exiles—for exam-

ple, unsuccessful rivals for the throne—who were

forced to seek their fortune abroad. Such men were

often willing to stay abroad to serve Frankish or By-

zantine rulers as mercenaries, to accept fiefs from

them, and to become their vassals. They thereby be-

came a factor in European politics. Vikings were fre-

quently employed by one European prince against

another or against other Vikings.

A voting assembly of freemen called thing was

a governing institution widely used by the ancient

Germanic peoples—it served as a forum to settle

conflict and to cast decisions on questions relating

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

418

ANCIENT EUROPE

to fencing, construction of bridges, clearance, pas-

ture rights, worship, and even defense. At the be-

ginning of the Viking Age, there were many thing

assemblies throughout Scandinavia, and Norse set-

tlers frequently established things abroad. The Ice-

landic Althing was unusual, however, in that it unit-

ed all regions of an entire country under a common

legal and judicial system, without depending upon

the executive power of a monarch or regional rulers.

The Althing was established around

A.D. 930. Little

is known about its specific organization during the

earliest decades, because the only description of this

exists in writing in Gra˚ga˚s and the sagas. These were

not contemporary sources but were compiled by

Christian scholars three hundred years after the end

of the Viking Age and therefore generally portray

the assembly as it was after the constitutional re-

forms of the mid-960s.

The social stratification of early Viking commu-

nities was based on wealth and property. Earls, peas-

ants, and thralls supported the socioeconomic lad-

der. Women quite often achieved higher status, as

evidenced through burial mounds in many parts of

Norway. Vikings were intolerant of weakness and it

is postulated from later literature that the elderly

and infirm were regarded as a burden.

The Vikings, who were probably inspired

through their contact with Europe and exposure to

the Latin writing system, developed their own al-

phabet called futhark or otherwise known as a runic

alphabet. Runes were carved primarily on stone but

some have been found in wood and bone. The

runes carried a multitude of meanings from the

mystical to the mundane. The earliest written

sources that provide information about the Vikings

(sagas and eddas), were created by Icelandic scribes

three centuries after the end of the Viking Age.

These sources, along with direct data from environ-

mental and archaeological investigations, help to

elucidate the complex and often misrepresented

Nordic people.

See also Viking Harbors and Trading Sites; Viking

Ships; Viking Settlements in Iceland and

Greenland; Hofstaðir; Viking Settlements in

Orkney and Shetland; Viking Dublin; Viking

York; Pre-Viking and Viking Age Norway; Pre-

Viking and Viking Age Sweden; Pre-Viking and

Viking Age Denmark (all vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Almgren, Bertil, et al., eds. The Viking. Gothenburg, Swe-

den: A. B. Nordbok, 1975.

Batey, Colleen E., Judith Jesch, and Christopher D. Morris,

eds. The Viking Age in Caithness, Orkney, and the North

Atlantic. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,

1995.

Morris, Chris. “Viking Orkney: A Survey.” In The Prehistory

of Orkney. Edited by Colin Renfrew. Edinburgh: Edin-

burgh University Press, 1985.

Myhre, Bjorn. “The Royal Cemetery at Borre, Vestfold: A

Norwegian Centre in a European Periphery.” In The

Age of Sutton Hoo: The Seventh Century in North-

Western Europe. Edited by Martin Carver, pp. 301–313.

Woodbridge, U.K.: Boydell, 1992.

———. “Chieftains’ Graves and Chiefdom Territories in

South Norway in the Migration Period.” Studien zur

Sachsenforschung 6 (1987): 169–187.

Nordisk Ministerra˚d og forfatterne. Viking og Hvidekrist:

Norden og Europa 800–1200. Copenhagen: Nordisk

Ministerra˚d, 1992.

Sawyer, Peter. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

———. Kings and Vikings: Scandinavia and Europe,

A.D.

700–1100. London: Methuen, 1982.

S

OPHIA PERDIKARIS

■

VISIGOTHS

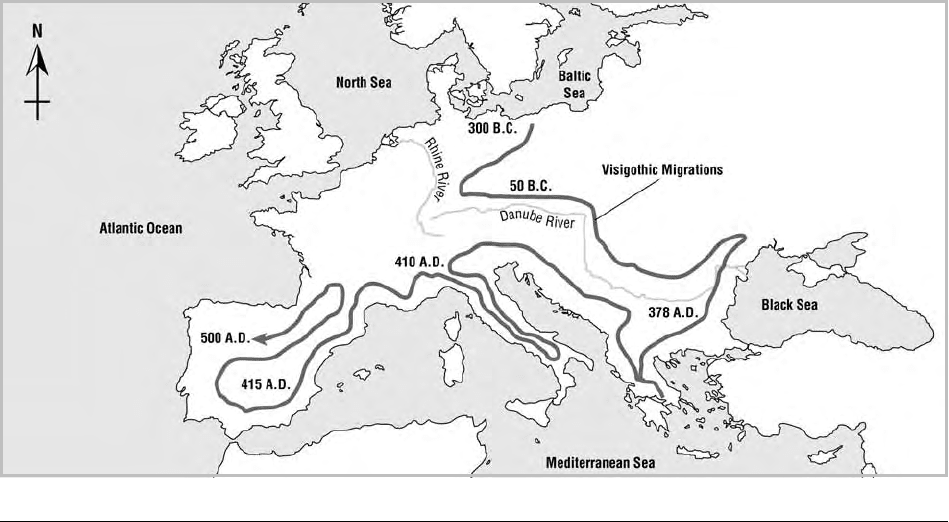

The Visigoths (Good Goths) were located in central

Germany when they first came into contact with

Roman traders and soldiers in the first century

B.C.

They were an Indo-European people who seemed

to have originated in Poland and not in Scandinavia,

as some ancient historians believed. Around 300

B.C. some of these people left Poland for unknown

reasons and began migrating south through the

Balkans. When they reached the borders of the

Roman Empire, the ancestors of the Visigoths

found it easier to settle down than to continue

south by fighting the Romans, and there they

stayed, along the Danube River on the borders of

the Roman Empire. They were small farmers, grow-

ing mostly wheat and barley.

Throughout the Roman Imperial period, the

ancestors of the Visigoths constantly traded with

the Romans and intermittently fought with them.

VISIGOTHS

ANCIENT EUROPE

419

Extent of Visigothic migrations. DRAWN BY KAREN CARR.

Both sides benefited from this exchange of goods

and information. It was through this contact that

the Visigoths encountered new technologies and

products, such as blown drinking glasses and bot-

tles, writing, and poured concrete. In about

A.D.

300 the Visigoths converted to Christianity

through the missionary work of Roman Arians. The

Visigoths also taught the Romans their own military

techniques, and in the fourth century

A.D. many

Roman soldiers on the Rhine and Danube were

buried carrying Gothic weapons and wearing Goth-

ic clothing and jewelry.

Starting in about

A.D. 200, however, the situa-

tion of the Visigoths became untenable. The Huns,

leaving their homeland in eastern Siberia, had mi-

grated across Asia and were sweeping down

through Europe, pushing refugees ahead of them.

The Visigoths, attacked by the Huns, tried desper-

ately to move across the Danube into the safety of

the Roman Empire but found themselves trapped

between two powerful opponents. Perhaps as a re-

sult, they began to develop a more formal identity

and leadership. In

A.D. 378 the Visigoths took ad-

vantage of Roman military mistakes to kill the

Roman emperor Valens at the battle of Adrianople,

cross the Danube, and take over a piece of the Bal-

kans within the empire. The Romans were unable

to push the Visigoths out but refused to provide the

refugees with food, seeds, or tools so that they

could reestablish themselves as farmers.

A generation later, the Visigoths were still in the

Balkans, struggling as refugees and growing increas-

ingly angry. Their leader, Alaric, demanded food

and supplies from the Roman emperor Honorius in

Ravenna, but Honorius did nothing. In response,

Alaric took his entire people and began moving to-

ward Rome. Meeting no serious opposition, Alaric’s

army sacked the city of Rome in

A.D. 410. The Visi-

goths stayed only three days, because Honorius im-

mediately cut off food supplies to Rome. When they

left, the Visigoths headed south down the Italian

coast, apparently hoping to cross the Mediterranean

Sea to Africa. Most of Italy’s food came from Africa,

and the Visigoths thought of it as a promised land.

In the toe of Italy, however, a bad storm destroyed

the boats they were planning to use, and the Visi-

goths hesitated, having no experience with seafaring

and frightened by the storm. Unexpectedly, Alaric

died. Alaric’s brother-in-law Ataulf (Ataulphus or

Adolf) took over and led the Visigoths back up

north and past the Alps into southern France.

In

A.D. 409, however, the Vandals, Alans, and

Sueves had invaded Spain. Honorius now invited

the Visigoths to counterattack and get rid of these

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

420

ANCIENT EUROPE