Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Tours, writing in the A.D. 570s and 580s, reflects a

world where ethnic distinctions, though sometimes

mentioned, matter little compared with social striv-

ing, political allegiance, and of course, religion.

The conversion of the Frankish elites, at least in

a perfunctory sense, advanced rapidly, although this

was not understood by archaeologists such as Salin,

who tended to interpret furnished burial as a

“pagan” rite. The spectacular grave goods that ac-

companied a woman and a young boy, doubtless of

royal rank, who were buried within a funerary chap-

el in front of Cologne cathedral c.

A.D. 530/40

prove the contrary. This is not to deny that some

rural magnates might have resisted the new religion

for a time; it is plausible that the sixth-century cre-

mation burial under a small tumulus at Hordain,

near Douai, represents one such. As Michael Mül-

ler-Wille points out, however, the royal example, no

doubt enhanced by the prestige of holy men and of

ranking churchmen (the two need not coincide), of

martyr graves and ad sanctos burial (next to or near

a martyr or a saint-confessor) encouraged the

emerging magnate class to shift to more Christian

burial styles. Thus one finds numerous richly fur-

nished elite burials in family chapels: one was built

near the older tumulus at Hordain. The ornament

might include clearly Christian motifs, such as the

cross on the silver locket worn by a girl buried

around

A.D. 600 in a chapel in Arlon (Luxem-

bourg).

By this time “Frank” referred to those subject

to Frankish law, and the connotation of the term

had shifted from “the bold” to “the free,” that is,

free of the tax obligations that the kings tried to im-

pose on their “Roman” subjects. Even as writers,

such as Pseudo-Fredegar in the seventh century,

were developing myths of Frankish origins, real eth-

nic distinctions blurred: Roman names appeared in

Frankish families and vice versa, and funerary cus-

tom was more likely to reflect social distinctions or

regional identity or the new association of burial

with piety. In practice, Franks had come to signify

the elite and free families of the Merovingian king-

doms, particularly of Neustria and Austrasia.

See also Merovingian France (vol. 2, part 7); Tomb of

Childeric (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Böhme, Hörst-Wolfgang. Germanische Grabfunde des 4. Bis

5. Jahrhunderts zwischen unterer Elbe und Loire. 2 vols.

Munich: Müncher Beiträge zur Vor- und Frühge-

schichte, 1974.

Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas. 2 vols. Mainz, Germany:

Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1996. (Catalog from the

Reiss-Museum, Mannheim, of the largest exhibition of

Frankish archaeology, with many fundamental articles

by leading scholars.)

Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation

and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1988.

Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Translated with

an introduction by Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth,

U.K.: Penguin Books, 1974. (The principal narrative

source, written by a Gallo-Roman bishop of Tours dur-

ing the late sixth century.)

Heinzelmann, Martin. Gregory of Tours: History and Society

in the Sixth Century. Translated by Christopher Carroll.

Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

(Authoritative study of the principal historian of the

Franks.)

James, Edward. The Franks. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

Müller-Wille, Michael. “Königtum und Adel im Spiegel der

Grabkunde.” In Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas. Vol.

1, pp. 206–221. Mainz, Germany: Verlag Philipp von

Zabern, 1996.

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Eu-

rope,

A.D. 400–600. Translated by Edward James and

Columba James. University Park: Pennsylvania State

University Press, 1975. (A still-pertinent overview of

the period, with an excellent bibliography to 1975.)

Périn, Patrick, and Laure-Charlotte Feffer. Les Francs. Vol.

1, A la conquête de la Gaule. Vol. 2, A l’origine de la

France. Paris: Armand Colin, 1997. (Well-illustrated,

accessible overview with archaeological emphasis.)

Reichmann, Christoph. “Frühe Franken in Germanien.” In

Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas. Vol. 1, pp. 55–65.

Mainz, Germany: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1996.

Riché, Pierre, and Patrick Périn. Dictionnaire des Francs: Les

temps Mérovingiens. Paris: Bartillat, 1996.

Salin, Édouard. La civilisation mérovingienne d’après les sé-

pultures, les textes et le laboratoire. 4 vols. Paris: Picard,

1950–1959. (Although dated and much criticized, this

is still a fundamental work by the pioneer of twentieth-

century Merovingian archaeology in France.)

Todd, Malcolm. The Early Germans. Oxford: Blackwell,

1992. (Archaeological background.)

Zöllner, Erich. Geschichte der Franken bis zur Mittel des sechs-

ten Jahrhunderts. Munich: Beck, 1970.

B

AILEY K. YOUNG

MEROVINGIAN FRANKS

ANCIENT EUROPE

401

■

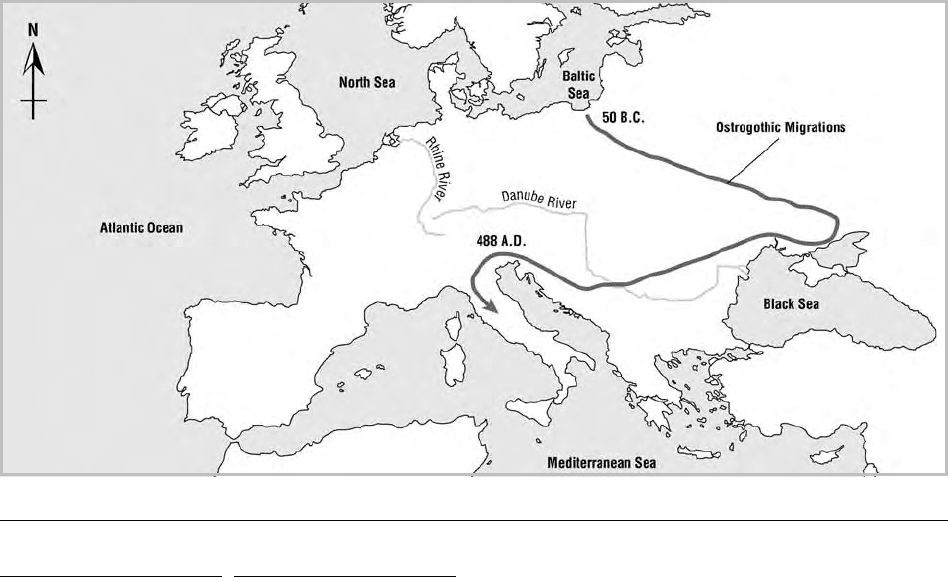

OSTROGOTHS

The Ostrogoths, like the Visigoths, were an Indo-

European group that first appears in the archaeolog-

ical record in Poland in the first century

B.C. From

Poland the ancestors of the Ostrogoths seem to

have migrated southeast rather than due south, as

did the ancestors of the Visigoths, and this is why

they are known as the Ostrogoths, or East Goths.

They finally settled down to farm in the Ukraine, on

the northern shores of the Black Sea. At that time

they probably were not unified as a group and did

not have a king.

In the course of the fourth century

A.D., howev-

er, the Huns, leaving eastern Siberia, migrated in a

group across northern Asia to the Ukraine, where

they pushed the Ostrogoths out of their traditional

homeland, forcing them to move to central Europe

(modern-day Austria). Even after moving to central

Europe, however, the Ostrogoths still suffered from

Hunnic harassment, and soon they were taken over

entirely by the Huns.

In

A.D. 453 Attila, the king of the Huns, died,

and his empire collapsed amid squabbling among

his weaker sons. The Ostrogoths were able to take

advantage of this disunity to break free of Hunnic

Extent of Ostrogothic migrations. DRAWN BY KAREN CARR.

control and reestablish their independence. Accord-

ing to tradition, they chose as their leaders three

brothers, one of whom was Theudemir. By the mid-

fifth century

A.D., the Ostrogoths increasingly were

involved with Roman politics. As a pledge for one

of the Ostrogothic arrangements with the Romans,

the Ostrogothic king Theudemir sent his own son,

Theodoric (Dietrich in German), to live at the

Roman court in Constantinople (modern-day Is-

tanbul). Theodoric was eight years old at the time,

and he therefore grew up culturally as Roman as he

was Ostrogothic. When Theodoric was eighteen, in

A.D. 475, his father died, and Theodoric returned

home to rule his people.

In

A.D. 476 the last of the Roman emperors in

the west, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by

Odoacer the Hun, who declared himself king of

Italy. The Roman emperor Zeno in Constantinople,

to the east, objected to this usurpation and tried to

put in his own candidate, Julius Nepos. Zeno, how-

ever, lacked the military manpower to send troops

to assert his authority in Italy. In 488 he therefore

invited the former hostage Theodoric, the young

king of the Ostrogoths, to invade Italy at the head

of his Ostrogothic army, on Zeno’s behalf. Theodo-

ric agreed, and his prompt invasion of Italy was en-

tirely successful. Odoacer was killed, and Theodoric

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

402

ANCIENT EUROPE

became the leader of Italy as well as the king of the

Ostrogoths.

Theodoric was an able and ambitious man, and

although he always maintained his allegiance to the

Roman emperor in Constantinople, he did very well

for himself in the west during his long reign. He

married a sister of Clovis, king of the Franks. The-

odoric sent one of his own daughters to be married

to the Visigothic king Alaric II, and when Alaric was

killed in the battle of Vouillé in

A.D. 507, he estab-

lished himself as regent for his young grandson

Amalaric. In this way Theodoric was able to rule

both Italy and Spain for much of his life, with vary-

ing degrees of influence over southern France as

well.

Under the rule of Theodoric, Italy seems to

have prospered as well. The archaeological evidence

suggests that people were still farming and the city

of Rome still functioning at this time, although

Rome certainly was losing population. Italy also was

part of a great Mediterranean world. Despite the

takeover of North Africa by the Vandals in

A.D. 429,

African red slip pottery continued to be imported to

Italy throughout the period of Ostrogothic rule.

When Theodoric died in

A.D. 526, he left no

sons. His grandson Amalaric (a cousin of the child

Amalaric above) succeeded him, with Theodoric’s

daughter Amalasuntha acting as regent for the ten-

year-old boy. Under Amalasuntha’s guidance, Ama-

laric was educated in the Roman fashion and learned

to read and write. Soon Amalasuntha’s influence

was shunted aside in favor of less Romanized advis-

ers, and Amalaric was diverted to more military and

traditional Ostrogothic pursuits, including heavy

drinking. On the death of Amalaric in

A.D. 534,

Amalasuntha became queen in her own right. She

took on her cousin Theodahad as her partner in

power, but Theodahad soon had Amalasuntha im-

prisoned and then, in 535, murdered.

By this time, the Byzantine emperor Justinian

I in Constantinople had noticed the weakness and

instability of Ostrogothic rule now that Theodoric

was dead, and he was preparing to invade. Justini-

an’s army, under the able general Belisarius, con-

quered North Africa in 533 and then, in quick suc-

cession, Sicily and Italy in 536. When Belisarius

landed at Naples, the Ostrogoths at first were de-

feated soundly. Justinian was suspicious of Belisari-

us’ loyalty, however, and recalled him to Italy; the

Ostrogoths seized the opportunity to revolt. The

war that ensued spanned twenty years and devastat-

ed Italy. In the end the Byzantine army prevailed,

and the last Ostrogothic king, Totila, was killed in

battle in

A.D. 552.

See also Goths between the Baltic and Black Seas (vol. 2,

part 7); Huns (vol. 2, part 7); Merovingian Franks

(vol. 2, part 7); Visigoths (vol. 2, part 7); Poland

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Heather, Peter. The Goths. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

Moorhead, John. Theoderic in Italy. Oxford: Clarendon

Press, 1992.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and

Local Society, 400–1000. London: Macmillan, 1981; rev.

ed., Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989.

Wolfram, Herwig. History of the Goths. Translated by Thom-

as J. Dunlap. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1988.

K

AREN CARR

■

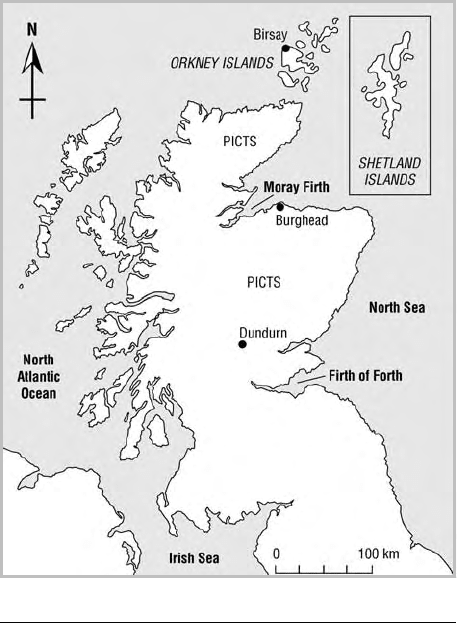

PICTS

A combination of enigmatic carved stones and a

written language (ogham script) that long defied in-

terpretation has ensured the mysterious aura of the

Picts. They were first named “Picti” in a Roman

panegyric written by Eumenius in

A.D. 297, but in

terms of their distinctive material culture, the evi-

dence is clearest from the sixth to the ninth centu-

ries. The twelfth-century source Historia Norvegia

describes the Picts as pygmies who lived under-

ground. The area of Pictish settlement is defined by

the distribution of placenames including for exam-

ple the element “pit” (as in Pitlochry, Pittenweem),

as well as by the widespread distribution of the

Picts’ distinctive symbol stones. The Picts are most

strongly associated with the eastern parts of Scot-

land, such as the regions of Fife and Angus in the

south, as well as the northern areas of Scotland in-

cluding the Sutherland and Caithness regions, and

the island groups of Orkney and Shetland. The

Roman term may well have been taken from the

Picts’ name for themselves, the Painted Ones, per-

haps due to their distinctive tattoos, but the term is

PICTS

ANCIENT EUROPE

403

a general one, encompassing the confederacy of

tribes in the north and east of Scotland (e.g., the

Caledones and Vacomagii).

THE HOUSES

Writing in 1955, Frederick T. Wainwright de-

scribed in The Problem of the Picts, the lack of evi-

dence concerning settlements and graves that

seemed to compound issues of place-names, myste-

rious symbol stones, and the simple—but seemingly

impenetrable—incised line script called “ogham.”

In Wainwright’s era, there were indeed more ques-

tions than answers about the Picts. The picture

changed beyond recognition, however, with several

excavations in the 1970s identifying not only dis-

tinctive dwellings but also unique burial sites. In the

early 1970s, excavation of a multiphase site at Buck-

quoy, Birsay, in Orkney revealed the first identified

Pictish dwellings, beginning as a simple three-cell

stone building and being replaced at a subsequent

phase of Pictish activity by more complex multicel-

lular structures of a more anthropomorphic form

(suggestive of a human form with a smaller head

than body, or of a figure eight in which the upper

General extent of Pictland.

circle is smaller than the lower). A few years later ex-

cavation added to this group a simple figure-eight

structure. All these buildings were located on the

mainland at Birsay in the northwest corner of main-

land Orkney and opposite the major Pictish and

Norse center of the Brough of Birsay. The Brough,

a small tidal island, had been investigated from the

1930s onward and provided details of extensive

metalworking activity in the Pictish period; it pro-

duced brooches comparable to those found in the

largest and most significant Pictish silver hoard in

Scotland—St. Ninian’s Isle, Shetland, in 1958. One

of the most famous icons of Pictish art was un-

earthed on the Brough of Birsay during excavations

in the 1930s: a shattered grave marker with three

warriors and Pictish symbols enigmatically pres-

ented on one face.

The identification of trefoil-shaped cellular

dwellings (possessing three main cells or rooms off

a central larger area with a hearth) as Pictish ensured

a reexamination of earlier excavations; many Iron

Age broch towers (defensive structures) that had ex-

tramural settlement of cellular form (cellular struc-

tures built around the tower that post-dated the

building and occupation of the tower), such as the

broch of Gurness in Orkney, later excavations at

the Howe in Orkney, or recent excavations at Scat-

ness in Shetland clearly demonstrate structural se-

quence and have greatly increased the Pictish cor-

pus. Excavations at Pitcarmick in Perthshire also

have been significant because they revealed a rectan-

gular Pictish structure, indicating that not all Pictish

buildings are celluar in form. Defended hilltops and

promontories were occupied by the Picts as well,

and sites such as Craig Phadraig near Inverness,

Dundurn in Perthshire, and Burghead on the south

side of the Moray Firth, all in mainland Scotland, in-

dicate a need for protection from enemies, both

Pictish as well as other neighbors.

THE BURIALS

Mainland Birsay in Orkney also has evidence of the

distinctive burial tradition used by the Picts, which

had not commonly been identified before work in

the late 1970s at Birsay and Sandwick in Shetland

in the north and at Garbeg and Lundin Links

among others on the Scottish mainland. The body

was laid in a simple cist, or stone box, often made

of a number of flat stones, without grave goods.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

404

ANCIENT EUROPE

The cist was covered over completely by sand or

earth and then a cairn, or mound of stones, was

built on top of that, delimited by a squared or

rounded curb or sometimes a ditch. In rare in-

stances there is evidence for the presence of a sym-

bol stone on top of the grave (for example at Wate-

nan in Caithness); perhaps more commonly the

grave was topped by a cairn made of small white

quartz pebbles. Old excavations failed to find the

burial beneath the layer of sterile soil or sand be-

neath the cairn, as in the case of Ackergill in Caith-

ness, excavated in the 1920s.

SYMBOL STONES, OGHAM SCRIPT,

AND PORTABLE OBJECTS

The iconic emblem of the Picts is the symbol stone.

There are three main types of stone monument:

Class 1 is the earliest (dating to about

A.D. 400–

700) and identifed as minimally shaped with incised

symbols of naturalistic form—for instance, animals

or crescents and V-rods (two rods set at right angles

to each other). Class 2 (dating to about

A.D. 700–

800s) combines careful shaping of the stone with

elaborate and naturalistic elements including

human figures and animals, as well as elaborate cross

motifs related to the Christian missions to Pictland

in c.

A.D. 710 of Nechtan (in his attempts to change

the Pictish church from Columban to Roman ob-

servance). Class 3 (dating to about

A.D. 750 on-

ward) is identified by Christian carvings including

elaborate crosses and by a complete absence of sym-

bols.

These stones have been studied extensively by

many scholars, but there has been no resolution as

to their specific function, although tribal boundary

stones or naming stones are among the more plausi-

ble of suggestions. However, the distinctive sym-

bols associated with the stones, clearly of Pictish ori-

gin, can also be found on smaller items of a more

portable nature; examples include symbols incised

on the terminal of large silver chains such as those

found at Gaulcross or Whitecleugh or those en-

graved on a silver plaque (or earring) from Norrie’s

Law, all in mainland Scotland.

Other categories of artifact that have been dis-

tinguished as specifically Pictish include short com-

posite bone combs, hipped pins (with a slight swell-

ing at mid-point of the shank that prevented

slippage during wear) of bone and copper alloy,

penannular brooches as found at St. Ninian’s Isle,

and simple painted pebbles. A stone spindle whorl,

excavated from Buckquoy in 2003, bears an ogham

inscription—one of thirty-six such inscriptions

identified in Pictland. The ogham script used by the

Picts is believed to have originated in Ireland during

the first centuries

A.D. and is based on single or small

groups of strokes that cross a single straight line.

Ongoing research seems to suggest that the script

originated from a Celtic language.

See also Dál Riata (vol. 2, part 7); Viking Settlements in

Orkney and Shetland (vol. 2, part 7); Dark Age/

Early Medieval Scotland (vol. 2, part 7); Tarbat

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ballin-Smith, Beverly, ed. Howe: Four Millennia of Orkney

Prehistory. Monograph Series, no. 9. Edinburgh: Soci-

ety of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1994.

Carver, Martin. Surviving in Symbols: A Visit to the Pictish

Nation. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1999. (An excellent

up-to-date summary.)

Dockrill, Steve, Val Turner, and Julie M. Bond. “Old Scat-

ness/Jarlshof Environs Project.” In Discovery and Exca-

vation in Scotland 2002. Edited by Robin Turner, pp.

105–107. Edinburgh: Council for Scottish Archaeolo-

gy, 2003.

Forsyth, Katherine. “Language in Pictland, Spoken and

Written.” In A Pictish Panorama. Edited by Eric Nicoll.

Forfar, Angus, U.K.: Pinkfoot Press, 1995.

Foster, Sally. Picts, Gaels, and Scots. London: B. T. Batsford/

Historic Scotland, 1996. (A excellent scholarly summa-

ry.)

Friell, Gerry, and Graham Watson, eds. Pictish Studies: Set-

tlement, Burial, and Art in Dark Age Northern Britain.

British Archaeological Reports, no. 125. Oxford: Tem-

pvs Reparatvm, 1984.

Hedges, John W. Bu, Gurness, and the Brochs of Orkney. Part

2, Gurness. British Archaeological Reports British Se-

ries, no. 164. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports,

1987.

Morris, Christopher D. The Birsay Bay Project. Vol. 1,

Brough Road Excavations 1976–1982. Department of

Archaeology Monograph Series, no. 1. Durham, U.K.:

University of Durham, 1989.

Ritchie, Anna. “Orkney in the Pictish Kingdom.” In The

Prehistory of Orkney

B.C. 4000–1000 A.D. Edited by

Colin Renfrew, pp. 183–204. Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press, 1985. (A full survey of evidence avail-

able to 1985.)

———. “Excavation of Pictish and Viking Age Farmsteads

at Buckquoy, Orkney.” Proceedings of the Society of An-

tiquaries of Scotland 108 (1976–1977): 174–227.

PICTS

ANCIENT EUROPE

405

Small, Alan, Charles Thomas, and David M.Wilson. St Nini-

an’s Isle and Its Treasure. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1973.

Wainwright, Frederick T., ed. The Problem of the Picts. Edin-

burgh: Nelson, 1955.

C

OLLEEN E. BATEY

■

RUS

The Rus are a people described in historical docu-

ments as traders and chiefs who were instrumental

in the formation of the ancient Russian state be-

tween

A.D. 750 and 1000. Historians and archaeol-

ogists have studied the Rus and their role in the de-

velopment of early Russian towns and the Russian

state.

HISTORICAL AND LINGUISTIC

EVIDENCE

The term “Rus” first appeared around A.D. 830 or

840 in western and eastern historical sources as a

designation for traders. Linguistic studies indicate

that the word is derived from the Finnish Ruotsi,

meaning “Swedes.” Ruotsi, in turn, is loaned from

the word that seafaring Swedes used to describe

themselves during the pre-Viking period. The sail-

ors used the Old Scandinavian rodr, characterizing

themselves as a “crew of oarsmen.”

From the beginning, then, Rus had both an

ethnic and a social (or professional) meaning—

indicating both “Scandinavian” and “seafarer.” In

eighth- and ninth-century historical documents, the

ethnic significance of Rus appeared predominant.

For example, an entry by Prudentius, bishop of

Troyes, for the year 839 in the Annales Bertiniani

records a diplomatic mission from Theophilus of

Byzantium to Louis the Pious of Ingelheim, ex-

plaining that men who called themselves “Rhos”

were “Swedes by origin.” Similarly, Liutprand,

Bishop of Cremona, after a visit to Constantinople

in 968, mentioned in his Antapodosis the “Rus,

whom we call by another name: Northmen.”

By the mid-tenth century, the term “Rus” had

changed in meaning to refer to the ruling class who

were instrumental in the establishment of the Rus-

sian state in Kiev. Scandinavians were present

among the retainers of the early Russian state, but

Rus now could be used to refer to all individuals be-

longing to this elite warrior group, Scandinavian or

not. An example of the new social meaning of Rus

is found in the Byzantine document De adminis-

trando imperio from around 950, which describes

the Rus in terms of their trade routes and the peo-

ples who owed them tribute. Once Rus lost its eth-

nic significance, a new term, Varangian, was used

to specify Scandinavians. The Russian Primary

Chronicle, compiled about

A.D. 1110, identifies

Rurik, the first ruler of Russia, as a Varangian, or

Swede.

On the basis of historical sources, eighteenth-

and nineteenth-century scholars concluded that

elite Scandinavians founded the Russian state, held

high rank and status in Russian society, and served

as mercenaries in Russia and Byzantium. Later

scholars, both historians and archaeologists, have

taken a more moderate view, arguing that Scandina-

vians had a significant role in early Russia but that

Slavic, Finno-Ugric, and Baltic peoples who settled

in the region also participated in the creation of the

early Russian state.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Excavations of early Russian towns provide evidence

of the social, political, and economic development

of the early Russian state, contributing significantly

to our knowledge of the Rus and their activities in

eighth- to eleventh-century Russia. The archaeo-

logical evidence does not prove the claims of the

Russian Primary Chronicle that Swedes founded

Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod, and other early Russian

towns, but it does suggest that Scandinavians may

have had a significant role in their early develop-

ment. Like the historical data, the archaeological

data show a gradual assimilation of the Rus into the

multiethnic society of the emerging Russian state.

Archaeological evidence indicates that early

Russian towns, such as Rurik Gorodishche and

Staraya Ladoga, had multiethnic populations, who

participated in an economy focused on long-

distance trade and craft production. During the

ninth and tenth centuries Rurik Gorodishche, for

example, imported goods from the Mediterranean,

the Baltic Sea, and Scandinavia. Scales and weights

indicate trade, and tools, production debris, and

raw materials suggest craft production. Early Rus-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

406

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Traders at a portage point along a Russian river. The boat holds trade goods such as

weapons. FROM OLAUS MAGNUS, HISTORIA DE GENTIBUS SEPTENTRIONALIBUS, PUBLISHED BY THE HAKLUYT

SOCIETY. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

sian towns had a function and nature similar to

those of other contemporary Baltic trade towns, in-

cluding Hedeby and Ribe in Jutland, Birka in cen-

tral Sweden, and Wolin in modern-day Poland.

Archaeologists have devoted much effort to in-

vestigating the ethnic identity of the traders and

crafts producers who lived and worked in early Rus-

sian towns. Their research shows that Slavic, Scandi-

navian, Baltic, and Finno-Ugric residents lived side

by side and engaged in similar activities, including

agriculture, craft production, trade, and military

service. Excavated burial sites associated with early

Russian towns imply significant cultural contact

among the various ethnic groups in ancient Russia.

This is seen in the mixture of Baltic, Finno-Ugric,

Scandinavian, and Slavic material in cemeteries of

the eighth to eleventh centuries—and even within

individual graves.

Because of the linguistic and historical evidence

suggesting that the Rus were Swedish, careful atten-

tion has been paid to the timing and nature of the

Scandinavian presence in early Russian towns. Scan-

dinavian artifacts are found in the earliest layers of

Staraya Ladoga and Rurik Gorodishche and com-

prise items that probably came to the town as per-

sonal possessions, not trade goods. Examples of

such finds include humble objects inscribed with

runes and characteristically Scandinavian orna-

ments, combs, footwear, and gaming pieces. One of

the most interesting features excavated at Staraya

Ladoga is a late eighth- or early ninth-century

smithy, containing tools and a bronze figurine of

Scandinavian style, hinting that the smith may have

been a resident Scandinavian.

Scandinavian graves have been reliably identi-

fied in many early towns, among them, Staraya La-

doga and Novgorod on the Volga trade route and

Gnezdovo/Smolensk and Kiev on the Dnieper

trade route. Based on their burials, the majority of

Scandinavians who were active in ancient Russia ap-

pear to have been traders and warriors. A limited

number of graves include both men and women, in-

timating that at least some Scandinavians were set-

tled in Russia, living a stable, domestic life. Com-

parisons of the Scandinavian finds with other graves

in Russia and Sweden give the impression that Scan-

dinavians were among the wealthier residents of

Russia (but not as wealthy as the elite class of Scan-

dinavia).

RUS

ANCIENT EUROPE

407

THE RUS IN EARLY RUSSIA

Altogether, the historical and archaeological evi-

dence suggests that the Rus were traders and crafts

producers, who were important to the economic

and political development of early Russian towns.

The cultural, social, and political processes of early

state development in Russia are reflected both in the

changing meaning of “Rus” through time and the

increasing homogenization of the material culture.

Originally referring to Scandinavian traders, the

name “Rus” soon came to mean any member of the

urban ruling class, who collected tribute from the

peoples settled in early Russia. Both the early Rus

traders and the later Rus chieftains were active in

and associated with towns. Archaeological finds

from burials and towns indicate that these traders

and chieftains included Scandinavians, together

with other ethnic groups. Both the historical and ar-

chaeological evidence show that the legacy of the

Rus—the development of towns and a specialized,

urban economy—were critical to the formation of

the early Russian state, unified under Kiev c.

A.D.

1000.

See also Russia/Ukraine (vol. 2, part 7); Staraya Ladoga

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Melnikova, Elena A., and Vladimir J. Petrukhin. “The Ori-

gin and Evolution of the Name Rus: The Scandinavians

in Eastern-Europe Ethno-political Process before the

Eleventh Century.” Tor 23 (1990–1991): 203–234.

Rahbeck-Schmidt, K., ed. Varangian Problems. Scando-

slavica supplement 1. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munks-

gaard, 1970.

Vernadsky, George, ed. A Sourcebook for Russian History

from Early Times to 1917. New Haven, Conn.: Yale

University, 1972.

R

AE OSTMAN

■

SAAMI

The Saami are an ethnic minority living in the arctic

and subarctic regions comprising contemporary

Norway, Sweden, and Finland as well as Russia’s

Kola Peninsula. Formerly their settlement area ex-

tended farther south to include the western White

Sea area of Russia and larger parts of Finland as well

as the interior of central and southern parts of Nor-

way and Sweden. Saami language belongs to the

Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic family, most

closely (although still distantly) related to Finnish in

the Baltic-Finnish language group. According to

historical linguists, Saami or Proto-Saami originated

due to a linguistic differentiation of a Proto-Finnish

language during the Bronze Age or even earlier.

Until the sixteenth century the Saami were pre-

dominantly hunters with a subsistence economy

based on terrestrial and maritime hunting as well as

fishing. The largest sociopolitical unit was the siida,

the local hunting band composed of five to ten nu-

clear families. Each siida occupied a clearly defined

territory where families lived dispersed at various

seasonal camps most of the year, aggregating for a

longer period only at the common winter site. Ex-

ogamy was practiced, forming affinal ties between

contiguous groups. Kinship was recognized bilater-

ally, as by most other circumpolar peoples. During

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the hunting

economy was gradually replaced or supplemented

by reindeer pastoralism, commercial fishing, and

small-scale cattle husbandry. According to some

scholars, however, the transition to reindeer pasto-

ralism had already taken place among the western

Saami during the Viking period.

“Saami” (Scandinavian samer) is the term prop-

erly used to denote the people who have been re-

ferred to popularly in the English-speaking West as

“Lapps” or “Laplanders.” It is a derivative of the

self-designating terms sámit, sáme, or saemieh, re-

flecting an etymological root that probably means

“land.” In historical records, however, a number of

ethnonyms have been applied to the Saami by out-

siders. In Norse sources from the Viking Age and

the medieval period, “Finns” (finner) is the com-

mon term, whereas “Lapps” prevails in Swedish,

Finnish (lappalaiset), and Russian (lop’) sources. It

is commonly held that the first written sources men-

tioning the Saami are descriptions by Tacitus (

A.D.

98) and Ptolemy (

A.D. c. 100–170) of the “Finns”

(Latin fenni and Greek Φιννοι/finnoi). According

to Tacitus the fenni live in “astonishing barbarism

and disgusting misery” without arms, horses, or

houses—their only shelter against wild beasts and

rain being a few intertwined branches. For want of

iron they tipped their arrows with sharp bone. Even

more astonishing to these authors is that the women

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

408

ANCIENT EUROPE

took part in the hunt on equal footing with men. It

is uncertain, however, if these early descriptions of

“Finns” actually refer specifically to the Saami or

more generally to Finno-Ugric speaking hunters of

northeasternmost Europe. A more certain ascrip-

tion is established by sixth-century Greek and

Roman writers adding the term scrithi or scere/cre

to the term fenni/finnoi, most notably in the writ-

ings of Procopius (scrithiphinoi) and Jordanes

(scerefennae, crefennae, rerefennae). The first term

must have been adopted from Norse language,

where skríða means “to ski”—that is, the combined

term means the “skiing Finns.” In the Norse culture

skriðfinner was a common term to designate the

mobile Saami hunters due to their skiing skills. This

stereotypical ascription is reflected in the Old Norse

oath that the enemy shall have peace as long as “fal-

con flies, pine grows, rivers flow to the sea, and

Saami are skiing.”

The ethnic origin of the Saami has long puzzled

Nordic and European scholars and opinions have

changed considerably. Until the mid-nineteenth

century it was commonly believed that the Saami

were the descendants of the aboriginal Stone Age

populations of Scandinavia (and even larger parts of

northern Europe). However, as political and scien-

tific currents turned the “noble savage” into the

“ignoble,” different readings of the archaeological

and historical record soon emerged. By the early

twentieth century the Saami were almost univocally

depicted as an “alien” people who had migrated to

Scandinavia from Russia or Siberia during the Iron

Age or even as late as the fourteenth or fifteenth

century. This doctrine of the Saami as an “eastern

other” prevailed in Nordic research well into the

post–World War II era.

Most historians and archaeologists have since

rejected the migration hypothesis in favor of models

claiming local origin. According to the most influ-

ential, the formation of Saami ethnicity (and even

the introduction of “Germanic” and Norse identity

in the north) was related to processes of social and

economic differentiation among the hunting socie-

ties in northern Fennoscandinavia during the first

millennium

B.C., processes concurring with in-

creased interaction with the outside world. Region-

al differences in cultural interfaces and exchange

networks promoted different cultural trajectories.

The coastal societies along the northwestern coast

of Norway and parts of the Gulf of Bothnia, relating

to the South Scandinavian Bronze Age culture,

adopted farming and developed chieftain-like sys-

tems with a redistributive socioeconomy. Subse-

quent processes of “Germanization” in the Roman

period have been interpreted as a conscious (al-

though imperative) choice among these societies to

obtain access to European exchange networks and

social alliances. The hunting population in the inte-

rior and the far north, however, became involved in

exchange networks extending eastward to metal-

producing societies in Karelia and central Russia.

Relating to these long-distance networks, supplying

bronze and iron, as well as to the new socioeconom-

ic and cultural interface caused by the “trans-

formed” coastal groups, ethnic boundaries and

symbolic systems of categorization emerged based

on a conscious distinction between “hunters” ver-

sus “farmers.” Thus, according to this model, Saami

ethnicity emerged as a social process of identity for-

mation among the “remaining” hunters of the

north.

Different suggestions about Saami origin are

provided by studies of genetic patterns in modern

Saami populations. Based on analysis of mitochon-

drial DNA it is claimed (although not uncontested)

that the Saami hold a unique position in the genetic

landscape of Europe. If so, the question remains as

to whether this uniqueness is due to their ancient

origin (and consequently isolation) or to a foreign

origin (and consequently migration)—or if the dis-

tinctive Saami genetic makeup even relates to mod-

ern social processes of kinship formation.

The Saami’s persistence as an ethnic group over

time can hardly be ascribed to their isolation. To the

contrary, for more than two millennia they have

been involved in close interaction with structurally

different neighboring societies. During the Iron

Age and the medieval period the Saami provided

highly valued hunting products such as exotic furs,

seal oil, walrus tusks, and probably falcons in return

for iron, textiles, and farming products. The charac-

ter of this early interaction is, however, disputed.

According to the “standard view” long held, the

Saami were the subject of exploitation and suppres-

sion from Norse chieftains and kings: the militarily

superior Norse gained access to Saami products

through taxation and fierce plundering raids. More

recent studies, however, claim that the Saami for the

SAAMI

ANCIENT EUROPE

409

most part interacted in a peaceful and mutually ben-

eficial way with their neighboring societies until the

medieval period. Indicative of this is the frequent

accounts in the Norse sagas of cooperation and

close relations. The sagas emphasize the Saami as

good hunters, as helpers, and as skilled boatbuild-

ers, as well as healers, fortune-tellers, and teachers

of magic and seid (shamanistic practices). Many

scholars argue that ample evidence suggests that the

Saami and their Germanic or Norse neighbors

shared fundamental religious conceptions and val-

ues (based in a common shamanistic worldview),

which may well have promoted tolerance and

smoothed coexistence. As bonds of interethnic de-

pendencies developed during the Iron Age the

Saami achieved considerable economic and ideolog-

ical power. Saami hunting products were crucial to

the Norse chieftains’ ability to participate in the Eu-

ropean prestige-goods economy, and their “magi-

cal” knowledge and ritual skills were desired and re-

spected. Studies have argued that during the Viking

period these bonds of dependencies were reinforced

by ritual gift exchange and interethnic marriages.

Such strategies for strengthening inter-ethnic

bonds may partly be seen as a response to the new

cultural and socioeconomic conditions that

emerged from the tenth century onward. The

Saami, who during the Iron Age related more or less

exclusively to the redistributive system of neighbor-

ing chieftains, now encountered the power politics

of surrounding state societies competing for control

over their resources. The emergence of the city-

state of Novgorod in the east involved the Saami in

extensive networks of fur trade. In Norway the

northern chieftains were defeated by the emerging

all-Norwegian kingdom that simultaneously con-

verted the Norse to Christianity.

The economic, social, and religious changes

both in the west and the east had a deep impact on

interethnic relations and exposed the Saami to new

economical and cultural pressures. The fur trade en-

forced increased production and pressure on re-

sources while political and religious changes in the

Norse society caused severe changes in their long-

term social and ideologically embedded relations

with the Saami. The archaeological record from the

Viking Age and the early medieval period provides

some indication of how this “stress” was negotiated

within Saami societies. Most notable is the rapid in-

tensification and spread of certain ritual practices,

such as burial customs (including bear burials) and

metal sacrifices. The formalization and unification

of material expressions is also exemplified in dwell-

ing design and spatial arrangements of settlements.

This ritual and symbolic mobilization may be read

as an attempt to overcome or neutralize the threats

from outside. However, archaeological and histori-

cal data clearly indicate that Saami societies did

change during this phase, and at least in some areas

the changes led to more complex social configura-

tions.

See also Iron Age Finland (vol. 2, part 6); Pre-Viking

and Viking Age Norway (vol. 2, part 7); Pre-Viking

and Viking Age Sweden (vol. 2, part 7); Finland

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hansen, Lars Ivar. “Interaction between Northern Europe-

an Sub-arctic Societies during the Middle Ages: Indige-

nous Peoples, Peasants, and State Builders.” In Two

Studies on the Middle Ages. Edited by Magnus Rindal,

pp. 31–95. KULTs skriftserie 66. Oslo, Norway:

KULT, 1996.

Hansen, Lars Ivar, and Bjo

⁄

rnar Olsen. Samenes historie [His-

tory of the Saami]. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen, 2003.

Mundal, Else. “The Perception of the Saamis and Their Reli-

gion in Old Norse Sources.” In Shamanism and North-

ern Ecology. Edited by Juha Pentikäinen. Religion and

Society 36. New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1996.

Price, Neil. The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron

Age Scandinavia. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala Universi-

ty, 2002.

Olsen, Bjo

⁄

rnar. “Belligerent Chieftains and Oppressed

Hunters? Changing Conceptions of Inter-Ethnic Rela-

tionships in Northern Norway during the Iron Age and

Early Medieval Period.” In Contacts, Continuity, and

Collapse: The Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic.

Edited by James Barrett. York Studies in the Early Mid-

dle Ages 5. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2003.

Storli, Inger. “A Review of Archaeological Research on Sami

Prehistory.” Acta Borealia 3, no. 1 (1986): 43–63.

Zachrisson, I. “A Review of Archaeological Research on

Saami Prehistory in Sweden.” Current Swedish Archae-

ology 1 (1993): 171–182.

L

ARS IVAR HANSEN, BJO⁄ RNAR OLSEN

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

410

ANCIENT EUROPE