Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Goths as coming from Scandinavia, an already orga-

nized “people,” to subordinate the region of the

lower Vistula, only to migrate later toward the Black

Sea and then to the west. Instead, one can envisage

a story of a long development and gradual changes

with no clear beginning and no end, a story that

should not be equated with the heroic history of

Gothic kings as described by ancient authors.

See also Ostrogoths (vol. 2, part 7); Visigoths (vol. 2,

part 7); Germany and the Low Countries (vol. 2,

part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bierbrauer, Volker. “Goten. II. Archäologisches.” In Real-

lexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 12: 407–

427. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1998.

———. “Archäologie und Geschichte der Goten vom 1–7

Jahrhundert. Versuch einer Bilanz.” Fruhmittelalter-

ichen Studien 28 (1994): 51–171.

Godłowski, Kazimierz. The Chronology of the Late Roman

and Early Migration Periods in Central Europe. Kra-

ków, Poland: Uniwersytet Jagiellon´ski, 1970.

Heather, Peter. The Goths. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

Kmiecin´ski, Jerzy. “Problem of the So-called Gotho-

Gepiden Culture in the Light of Recent Research.” Ar-

chaeologia Polona 4 (1962): 270–285.

Kokowski, Andrzej. Grupa masłome˛cka: Z badan´ przemiany

kultury Gotów w młodszym okresie rzymskim [The

Masłome˛cz Group: From studies of changes in the cul-

ture of the Goths during the Early Roman Age]. Lublin,

Poland: Uniwersytet Marii Curie–Skłodowskiej, 1995.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, Jerzy. “Próba identyfikacji archeologicz-

nej ludów bałtyjskich w połowie pierwszego tysia˛clecia

naszej ery” [Attempt at archaeological identification of

Baltic peoples in the mid-first millennium

A.D.]. Bar-

baricum 1 (1989): 64–100.

Wolfram, Herwig. “Origo et religio: Ethnic Traditions and

Literature in Early Medieval Texts.” Early Medieval Eu-

rope 3, no. 1 (1994): 19–38.

———. Geschichte der Goten: Von den Anfängen bis zur

Mitte des sechsten Jahrhunderts. Entwurf einer histor-

ischen Ethnographie. Munich: C.H. Beck, 1979.

Woła˛giewicz, Ryszard. Ceramika kultury wielbarskiej mie˛dzy

Bałtykiem a Morzem Czarnym [Pottery of the Wielbark

culture between the Baltic and Black Seas]. Szczecin,

Poland: Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie, 1993.

———. “Kultura wielbarska—problemy interpretacji etnicz-

nej” [The Wielbark culture—problems of ethnic identi-

fication]. Problemy kultury wielbarskiej. Słupsk: Wyz˙sza

Szkoła Pedagogiczna (1981): 79–106.

P

RZEMYSŁAW URBAN

´

CZYK

■

HUNS

The Huns included Asiatic peoples speaking Mon-

golic or Turkic languages who dominated the Eur-

asian steppe from before 300

B.C. In the third cen-

tury

A.D. the Great Wall of China, 2,400 kilometers

long, was built to fend off “western barbarians.”

The reverse impact of attacks set off a domino effect

of westward migrations. Just after

A.D. 370 the

Huns crossed the Volga River and conquered the

Alans, who had dominated the steppe north of the

Caucasus Mountains for millennia. The Huns de-

stroyed the Ostrogothic empire in the Dnieper–

Don interfluve in

A.D. 375 and defeated the Visi-

goths at the Dniester River the next year. In his

work Getica the sixth-century historian Jordanes

described a century of Hun subjugation, with Latin

translations of passages from eyewitness accounts by

the Byzantine Rhetor Priscus. Copies of this compi-

lation biased medieval historiography. Records by a

Roman officer, Ammianus Marcellinus, from the

late fourth century

A.D. form another collection of

topics (beginning with the Greek historian Herodo-

tus in the fifth century

B.C.) that still may be found

in the curricula of many European schools.

Roman infighting in

A.D. 395 permitted the

Huns to conquer the Roman Balkan provinces and

then invade present-day southern Poland. In 406

fleeing German peoples broke into the western

Roman Empire at the Rhine. The Huns exploited

this situation by offering lucrative mercenary ser-

vices to the Romans against the intruders. After at-

tacking the Balkans, the Huns moved the seat of

their empire into the southern Great Hungarian

Plain in about 425. Several late Sarmatian settle-

ments in this area show evidence of violent destruc-

tion. The Romans paid Hun mercenaries in money

and war booty and provided them access to Roman

areas ravaged by Germanic migrations, including

Pannonia (

A.D. 434). The Huns’ expansion is

marked by finds in more than 150 archaeological

sites across the Carpathian Basin. The finds include

large metal cauldrons in Hungary (fig. 1), which are

also depicted in rock art in the Altai Mountains in

Siberia and southern Russia and western Mongolia.

The empire of the Huns filled a geopolitical vac-

uum between the two Roman Empires and even

acted as a power broker. Huns conducted ambitious

HUNS

ANCIENT EUROPE

391

Fig. 1. Several such large “sacrificial” metal cauldrons have

been recovered in the Carpathian Basin as well as in Hun

territories across Eurasia. PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDRÁS DABASI.

HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

military campaigns in both directions. They raided

Byzantine territories (

A.D. 408, 441–443, and 447–

449), occupying a series of cities and approaching

Constantinople. In 442 the Huns extorted 6,000

pounds of “war compensation” plus 2,100 pounds

of gold annually from Byzantium. This was the hey-

day of their empire. In 445 Attila, the new king of

the Huns, attacked the western Roman Empire. He

turned back before Ravenna, however, after an

earthquake in 447 destroyed the Theodosian Wall

in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), built

against the Huns in 408. Damage to the wall left the

city vulnerable. The allied Gepid and Ostrogothic

infantries slowed Attila’s move on Constantinople,

allowing months for the reconstruction of the wall.

The siege was canceled, but the Huns conducted

prolonged peace negotiations with Byzantium. It

was then that Rhetor Priscus, who documented the

last decades of the Hun empire (434–455), visited

Attila’s court in 449 with a Byzantine delegation.

Possibly under Byzantine inspiration, Attila

moved west in 451, until the Romans and Visigoths

and their allies stopped him at Orléans. His army

united Gepids, Ostrogoths, Skirs, Alans, and Sarma-

tians, who faced fellow barbarians in the battle of

Catalaunum. Fighting to a draw, the Huns retreat-

ed to the Great Hungarian Plain. Early in

A.D. 452,

Attila raided northern Italy, advancing beyond Me-

diolanum (modern-day Milan). In the summer,

however, he was forced back by heat, epidemics,

and the news that Byzantine forces had crossed the

Danube River into Hun territory. Early the next

year, amid preparations against Byzantine intrusion,

Attila died unexpectedly. Subsequent infighting

weakened the empire, and even his victorious son

could not quell vassals, who defeated the Huns

under Gepid leadership (

A.D. 455). The Huns fled

toward the Pontic steppe. Barbarians emerging after

Hun rule finished off both Roman Empires, al-

though written sources attribute much of this de-

struction to the Huns.

Although western chroniclers of the fifth

through seventh centuries detailed Attila’s plunder-

ing of Gaul and Italy (451–452), the exploits of the

Huns in Byzantium remained underrepresented in

the historical record. Medieval Catholic propaganda

also profited from an unauthenticated encounter

between Pope Leo I and Attila. The bishop of

Rome became the savior confronting “flagellum

dei” (scourge of God), Saint Augustine’s term for

Gothic King Alaric transposed to Attila in medieval

Italy. Attila’s popular descriptive, “the Dog-

Headed,” is a reminder of artificial skull deforma-

tion, a custom evidenced in fifth-century burials in

the Hun confederacy. Attila’s life spans nearly a

hundred and twenty-four years in documents, of

which he spent forty-four as king. In reality, he

ruled for eight years before dying at about the age

of forty-five.

In German tradition Attila’s image varied be-

tween bloodthirsty despot and generous monarch.

Christian Hungarians started considering Hun an-

cestry when the Nibelungenlied, a High German

epic, was written in about 1200. Although the

Turkic name Onugarian had been used haphazardly

in western sources to denote Magyars (Ungar,

Hungar, and Vengr) and other warlike equestrian

barbarians, it was not linked specifically with Huns

(Hsiung-nu) until the Middle Ages. In about 1283

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

392

ANCIENT EUROPE

Simon Kézai, “a loyal priest,” crafted an influential

legend comparable to the Niebelungenlied with a

heavy Hungarian emphasis. It was dedicated to

King László IV of eastern Cumanian extraction,

who was involved in a power struggle with his no-

blemen and the church. An apocryphal relation to

Attila possibly attained paradigmatic significance

when steppic tradition had to be reconciled with

Christianity.

Despite differences in ethnohistory, language,

and physical makeup, the images of Huns and con-

quering Hungarians hopelessly converged. Coinci-

dentally, both Huns and Magyars launched ruthless

raids on their neighbors and beyond from the Car-

pathian Basin, but with a five-hundred-year time

gap between them (Huns in 425–452 and Hungari-

ans in 899–955). Their renowned light cavalry tac-

tics also were similar. By the sixteenth century the

Hungarian nobility were considered the glorious

descendants of Huns who had re-conquered Attila’s

empire. In the nineteenth century the theory of

Hun ancestry spread without social content in the

public education system in Hungary, and the myth

has become “historical knowledge,” periodically re-

suscitated even today.

In contrast to this passionate historical interest,

the Huns have been studied archaeologically in

Hungary only since 1932. The three tumultuous

decades of their empire left a rich but scattered ar-

chaeological heritage in Hungary. (Even in central

Asia only a very few Hun finds predate the fourth

century

A.D.) Stylistically, Alans and Germanic

tribes shared many predominantly “Hun” elements

in their attire. “Cicada” brooches represent one of

the characteristic artifact types. The archaeological

traces of the Huns include not only grave goods and

hoards but also destruction layers at Antique settle-

ments. Crude architectural structures over such

strata often are linked to Hun occupation.

See also Animal Husbandry (vol. 2, part 7); Hungary

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bóna, István, A hunok és nagykirályaik [The Huns and their

great kings]. Budapest, Hungary: Corvina, 1993.

Daim, Falko, ed. Reitervölker aus dem Osten: Hun-

nen+Awaren. Schloss Halbturn, Austria: Burgenländ-

ische Landesausstellung, 1996.

Kovács, Tibor, and Éva Garam, eds. A Magyar Nemzeti

Múzeum régészeti kiállításának vezet˝oje (Kr. e.

400,000–Kr. u. 804) [Guide to the archaeological ex-

hibit of the Hungarian National Museum]. Budapest,

Hungary: Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, 2002.

Lengyel, A., and G. T. B. Radan, eds. The Archaeology of

Roman Pannonia. Lexington: University Press of Ken-

tucky, and Budapest, Hungary: Akadémiai Kiadó,

1980.

L

ÁSZLÓ BARTOSIEWICZ

■

LANGOBARDS

The Langobards, “Long-beards,” also known in

modern literature as Lombards or Longobards,

were not among the many large tribal and confeder-

ate groupings who assailed the Roman Empire in its

last centuries in the West. Although Langobards are

recorded by the Roman historian Tacitus in his first-

century ethnographic survey, Germania (chap. 40),

and noted as “famous because they are so few,” later

Roman sources pass minimal comment on them, as

the Langobards did not force the Rhine or Danube

as the Alemanni or Goths achieved in the third and

fourth centuries

A.D. Although much is written now

on ethnogenesis (the creation and formulation of

new powers such as the Franks) in these crucial cen-

turies, the Langobards stand out for their antiquity

and resilience: Indeed, Tacitus describes how they

were a tribe “hemmed in . . . by many mighty peo-

ples, finding safety not in submission but in facing

the risks of battle”—this helping them to persist as

a name into the Early Middle Ages unlike other

tribes listed by Tacitus, as, for example, the Reu-

dingi and Eudoses. Archaeologically, the Langobar-

dic presence in the early Roman imperial period is

somewhat uncertain, although urnfields (cremation

cemeteries) along the lower Elbe and in Lower Sax-

ony, featuring weaponry as well as Roman imports,

are attributed to the tribe. It is disputed how far the

archaeological data inform on territory and ethnici-

ty, but indications of change and demographic loss

are suggested for the third century. Later textual

sources argue for a southeastwardly migration of the

Langobards toward Bohemia and thence the Mid-

dle Danube. It is doubtful that this movement can

be easily tracked through a distinctive cultural resi-

due, such as burial goods, yet any “migration” will

have involved much more than the movement and

LANGOBARDS

ANCIENT EUROPE

393

carrying of a name: ancestral bonds and badges of

identity and belonging to the Langobardic name

should have been preserved through language, ti-

tles, artifacts, and ritual, even if these also evolved

with time.

Although knowledge of the earliest phases of

Langobardic development and history-making re-

mains somewhat insecure, a sixth-century promi-

nence is well attested through both text and archae-

ology. A contemporary source, the Greek historian

Procopius, records alliances forged in the 530s–

550s

A.D. between the Byzantine emperor Justinian

and the Langobards in the context of the Byzan-

tine-Gothic War in Italy (A.D. 534–555). The Lan-

gobards in the second quarter of the sixth century

occupied the northern portions of former Roman

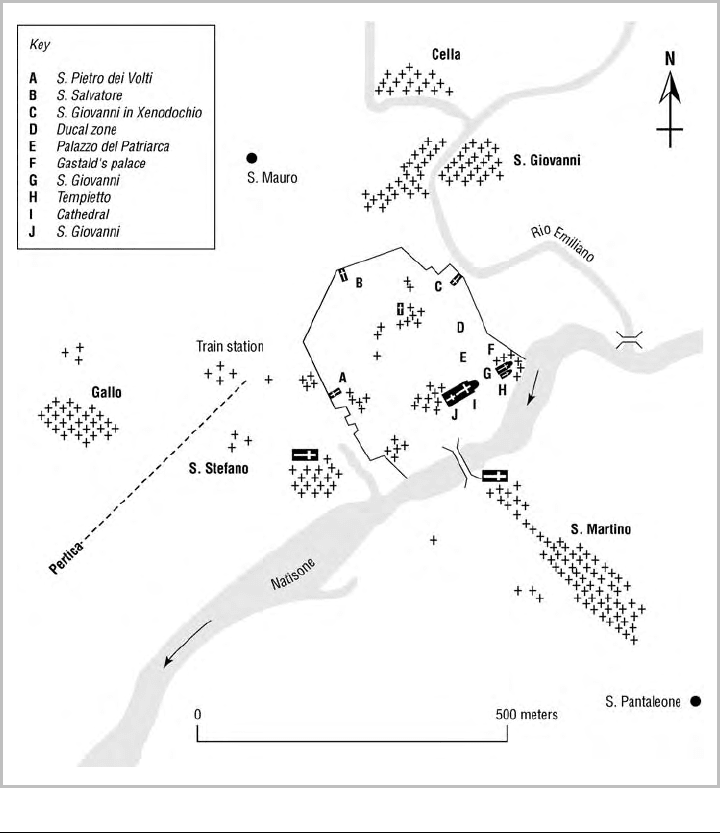

Fig. 1. Site plan showing Cividale and the distribution of cemeteries. ADAPTED FROM BROZZI 1981.

Pannonia (western Hungary); southern Pannonia

was largely ceded, along with much tribute, by Jus-

tinian to secure the landward passage of imperial

troops to Italy. Langobardic soldiers also fought in

the Byzantine armies in Italy, and various chiefs be-

came imperial officers, serving in the Balkans and

even in Persia. Procopius records the Langobards as

Christian and Catholic allies in the 540s, although

Arianism and paganism remain evident into the sev-

enth century.

The late-eighth-century Langobardic historian

and poet Paulus Diaconus, writing chiefly for the

court of Charlemagne, provides much of the docu-

mentation for the subsequent Langobardic occupa-

tion of large parts of Italy in opposition to the By-

zantines. The Byzantines, who had only defeated

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

394

ANCIENT EUROPE

the Ostrogoths in the peninsula after a disastrously

long and drawn-out conflict, appear little able to

counter the Langobardic migration of

A.D. 568, de-

spite calling on Frankish support and using gold to

buy off Langobardic dukes. Numbers involved in

the migration are disputed, but a military compo-

nent (that is, adult males) is estimated at about forty

thousand. By c.

A.D. 610 the Langobards held the

bulk of northern Italy except for the coastal zones

of Venetia and Liguria, and they had limited the im-

perial forces to a central Italian land corridor linking

Rome and Ravenna; the king was based first in Ve-

rona, then Milan, and finally settled in Pavia. Terri-

tories were divided up chiefly among dukes based in

towns and fortresses. Further territorial gains were

made in the mid-seventh and mid-eighth centuries

when the Byzantine capital Ravenna was occupied.

With the ejection of Byzantine rule in central and

northern Italy, papal Rome successfully appealed to

the Carolingian Frankish court, culminating in

Charlemagne’s conquest of the regnum Langobar-

dorum in

A.D. 774. Powerful Langobardic principal-

ities nonetheless endured in central southern Italy,

notably focused on Benevento.

Ninth-century Benevento marked a significant

Langobardic cultural flourish: in addition to the

Langobard’s major palace and religious foundations

in the city itself, Langobardic princes and elites con-

tributed strongly to monastic seats, notably San

Vincenzo al Volturno, which had been founded c.

A.D. 703 by three Langobardic brothers and monks.

The ninth century witnessed substantial remodeling

and aggrandizement of the abbey through Lango-

bardic and Frankish patronage. In particular, exca-

vations have revealed the extensive use of elaborate

wall paintings; San Vincenzo also featured a major

scriptorium producing high-quality manuscripts,

some still extant. In northern and central Italy,

eighth-century Langobardic churches and monaste-

ries are attested by text, art, architecture, and

archaeology, such as in the royal or ducal cities

of Pavia and Verona. Exquisitely ornamented

monasteries such as the Tempietto at Cividale and

San Salvatore at Brescia survive to reveal not just re-

ligious fervor by the Langobardic elites but also a

major cultural renaissance, prominent before direct

Carolingian influence.

Although walled towns are attested as seats of

power (for kings, dukes, lieutenants, and counts),

related settlement archaeology remains extremely

limited: houses are known in Brescia and Verona,

for example, and traces of palaces are claimed for

Brescia, Cividale, and Spoleto, but in terms of rural

sites, specific Langobardic-period housing is barely

known (with the picture even more scarce for Lan-

gobardic Pannonia). This deficiency, however, ex-

tends also to non-Langobardic sites, including

Rome and Ravenna, where sixth-to-eighth-century

secular structures remain to be fully identified ar-

chaeologically. Excavations at Brescia in particular

have shown how towns were severely depleted c.

A.D. 600, with open spaces, timber and rubble

buildings, robbed classical structures, and burials in-

truding into the urban confines. Nonetheless, the

identification of towns as seats of authority suggests

continuity of population, with the bulk of these in-

habitants being Italian/Roman and non-

Langobardic.

This continuity of population has implications

for the chief source of archaeological information

for the sixth and seventh centuries, namely burials.

Major excavated necropolises include Nocera

Umbra and Castel Trosino in central and eastern

Italy and Testona (near Turin) and Cividale in the

north; a key aristocratic group lies at Trezzo

sull’Adda near Milan. Although weapon burials are

prominent (and with elite presenting quality “pa-

rade” items—gilded or silvered spurs, decorative

shields—into the mid-seventh century), attention

has increasingly been given to other artifacts, nota-

bly dress fittings, can help identify patterns of inte-

gration or acculturation between Langobards and

natives. The discovery of workshops in Rome that

were the source of manufacture for items used in

Langobardic territories particularly demonstrates

exchange networks in the seventh-century peninsu-

la. These data complement texts such as the Lango-

bardic law codes to provide an ever fuller and more

complex image of Langobardic and Langobard-

period society and culture.

See also Coinage of the Early Middle Ages (vol. 2, part

7); Hungary (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bona, Istvan. The Dawn of the Dark Ages. The Gepids and the

Lombards in the Carpathian Basin. Budapest: Corvina

Press, 1976.

Brogiolo, Gian Pietro. Brescia altomedievale: Urbanistica ed

edilizia dal IV al IX secolo. Mantua, Italy: Padus, 1993.

LANGOBARDS

ANCIENT EUROPE

395

(Synthesis of the major excavations and archive data for

late antique and early medieval [Langobardic] Brescia.)

Brogiolo, Gian Pietro, Nancy Gauthier, and Neil Christie,

eds. Towns and Their Territories: Between Late Antiqui-

ty and the Early Middle Ages. Transformation of the

Roman World, vol. 9. Leiden: Brill, 2000. (Includes ar-

ticles on the Lombards, their settlement and defense in

Pannonia and Italy, and their eighth-century artistic

culture.)

Brogiolo, Gian Pietro, and Sauro Gelichi. Nuove ricerche sui

castelli altomedievali in Italia settentrionale. Florence:

All’Insegna del Giglio, 1996. (Detailed discussion of se-

quences of fortifications, identifying Langobardic con-

tribution.)

Brozzi, Mario. Il ducato longobardo del Friuli. Udine: Grafi-

che Fulvio, 1981. (Useful survey of sources and archae-

ology for one north Italian region.)

Christie, Neil. The Lombards: The Ancient Longobards. Ox-

ford: Blackwell, 1995.

Harrison, Dick. The Early State and the Towns: Forms of Inte-

gration in Lombard Italy,

A.D. 568–774. Lund, Sweden:

Lund University Press, 1993.

Hodges, Richard. Light in the Dark Ages: The Rise and Fall

of San Vincenzo al Volturno. London: Duckworth,

1997.

McKitterick, Rosamond, ed. The New Cambridge Medieval

History. Vol. 2, c. 700–c. 900. Cambridge, U.K.: Cam-

bridge University Press, 1995. (Contains key summary

historical papers on eighth- and ninth-century Lango-

bardic and Carolingian Italian society, government, and

religion.)

Paroli, Lidia, ed. La necropoli altomedievale di Castel Tro-

sino: Bizantini e Longobardi nelle Marche. Cinisello Bal-

samo, Italy: Silvana, 1995. (A series of papers with full

illustrative support linked to reevaluating the finds and

population as well as wider context of the well-known

Langobardic cemetery of Castel Trosino.)

Roffia, Elisabetta, ed. La necropoli longobarda di Trezzo

sull’Adda., Ricerche di archeologia altomedievale e

medievale 12/13. Florence, Italy: All’Insegna del

Giglio, 1986.

Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and

Local Society, 400–1000. London: Macmillan, 1981.

N

EIL CHRISTIE

■

MEROVINGIAN FRANKS

The Franks were one of the Germanic peoples who

conquered parts of the Roman Empire during the

Migration period (fifth century A.D.) and were unit-

ed into a powerful kingdom covering most of Gaul

under King Clovis (

A.D. 481/82–511). “Merovin-

gian” is the name of the dynasty he founded (taken

from the name of his perhaps legendary ancestor

Merovech), which reigned until

A.D. 751 and tradi-

tionally has been regarded as the first dynasty of the

kings of France. (The name France derives from this

people.) Who were the Franks, and where did they

come from?

The sixth-century bishop Gregory of Tours, the

principal narrative source, thought they came from

Pannonia (modern-day Hungary and parts of the

former Yugoslavia). In the next century a theory

emerged that they were descended from the Tro-

jans. The following centuries saw many extravagant

developments of these myths of national origin (in-

cluding notions that the Franks came from Phrygia

or from Scandinavia). In 1714 a scholar named

Fréret advanced what Patrick Périn has called the

“first really scientific theory” of their origin, that

they were born of a league of Germanic peoples

whose ancestors had fought Julius Caesar. The de-

velopment of Merovingian archaeology coupled

with criticism of the written sources since his day has

made this the consensus view.

Julius Caesar, writing in the 50s

B.C., and

Roman writers of the first century

A.D., such as Pliny

and Tacitus, describe a number of Germanic peo-

ples and discuss their customs; they make no refer-

ence to the Franks. The Franks seem to have

emerged as a coalition of smaller peoples mentioned

by these authors, such as the Chamavi, the Chat-

tuari, and the Bructeri, living along the Lower

Rhine and galvanized to join forces to attack the

third-century Roman Empire, weakened by civil

war. The new name, which comes from a root

meaning “the bold,” is cited in connection with a

barbarian force defeated near Mainz by the future

emperor Aurelian (r.

A.D. 270–275), and Franks

were exhibited in his triumph. Franks also are men-

tioned as dangerous pirates, whose depredations,

like those of the Saxons named with them, led to the

creation of a new system of military defenses along

the English Channel. Still others appear at this early

date as Roman allies, among them, King Genno-

baudes, who concluded a pact (foedus) with Rome

in

A.D. 287–288. By the time the emperors Diocle-

tian (r.

A.D. 284–305) and Constantine I (r. A.D.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

396

ANCIENT EUROPE

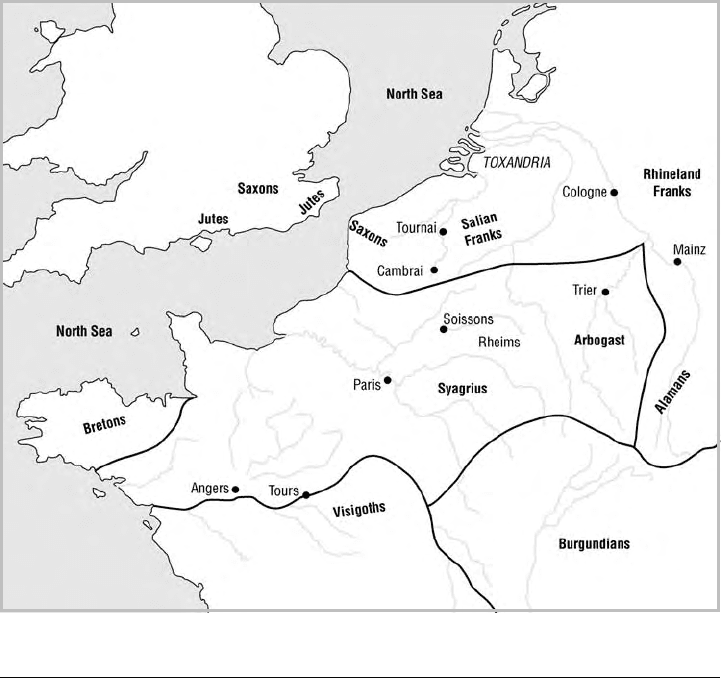

The traditional view of Syagrius’s kingdom, stretching across most of northern Gaul. ADAPTED FROM

JAMES 1988.

306–337) had restored the frontiers and the empire

as a highly centralized and militarized state, the

Franks were referred to often in their lower Rhenan

homeland, divided into groups of varied and shift-

ing allegiances.

Archaeologists have separated the early pre-

Migration Germans into three geographic group-

ings, primarily on the basis of ceramic types: (1) a

northern one, around the northern seacoasts; (2) an

eastern one, extending from the Elbe into Bohemia;

and (3) a western one, the “Rhine-Weser group.”

This seems to accord with the traditional division by

linguists of northern, eastern, and western dialects

of Old Germanic, although the evidence is based on

post-Migration sources. The material culture does

not itself suggest great differences in lifestyle among

these groups. They tended to live in small villages

with an economy that combined cereal agriculture

with animal husbandry (as Tacitus noted, wealth

was measured in cows).

A typical form of Germanic building to the

north, well known from such excavations as Biele-

feld-Sieker in Westphalia, was a long, rectangular,

timber-frame, thatched-roof building shared by

people and cattle. Various other timber-post con-

structions, including rectangular two-room houses

and small buildings with dug-out areas underneath

(causing them to be misleadingly labeled “sunken

huts”), which were used as workshops and for stor-

age, also are well documented. Much of the pottery

was handmade; it was often plain but might be dec-

orated with incised linear ornament or crude

stamps. Women did the weaving, spinning, and tex-

tile production and, along with the slaves, were re-

sponsible for the agricultural work, according to

Tacitus. Examples of textiles have been found on

the “bog bodies,” bodies thrown into the swamps

or marshes so soft tissue, clothing, and so on have

been preserved in this anaerobic environment. The

men were responsible for ironworking, a craft of

great prestige and technical complexity, largely car-

MEROVINGIAN FRANKS

ANCIENT EUROPE

397

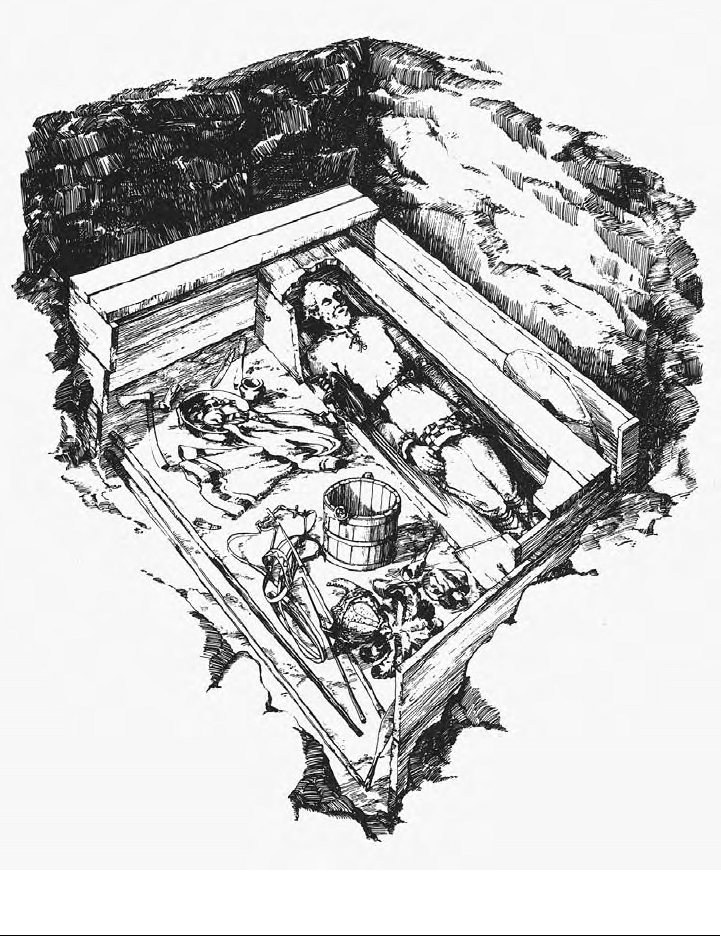

Fig. 1. Morken: a magistrate burial c. A.D. 600. FROM DAS GRAB EINES FRÄNKISCHEN HERREN AUS MORKEN

IM

RHEINLAND (1959). REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF BOHLAU VERLAG GMBH & CIE.

ried out by local smiths working with small quanti-

ties of ore in small ovens. Their supreme product,

a sword with a hard cutting edge and a core of softer

steel for greater flexibility, proved its worth in battle

with the Romans.

Tacitus emphasizes the warrior values of early

Germanic society, which was patriarchal in charac-

ter, based on clan groupings (called Sippe), and so-

cially divided into nobles, free warriors, and slaves.

His evocation of tribal assemblies, where the free

warriors clashed their weapons to voice assent to de-

cisions, misled nineteenth-century scholars eager to

find in them the roots of democratic institutions.

Research emphasizes the emergence of war kingship

and war bands as a dynamizing force at the time

when the Franci and other new, aggressive confed-

erations (Alemani) appear in the written sources. As

Patrick Geary points out, the pre-Migration Ger-

manic tribes were unstable groupings whose sense

of unity was forged by myths of common ancestry

and hence of pure blood. The thiudans, a man of

noble lineage linked to divine ancestors, was a kind

of religious king and a guarantor of law, social

order, fertility, and peace. The figure Tacitus called

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

398

ANCIENT EUROPE

a dux (general), chosen to lead the tribe in war and

chief of his own band of eager young warriors (a

comitatus), had become by the third century the

forger of a new kind of kingship (suggested by the

Celtic loanword reiks) and a new kind of cultural

identity.

The archaeological signatures of this new iden-

tity are the warrior graves and, in particular, what

have been called “chieftains’ graves.” The usual

form of burial in the Rhine-Weser culture, and

among the Germanic groups in general, had been

of cremated remains, often placed in an urn, with

few or no grave goods. In the late third century in-

humation burials with a rich variety of grave goods

begin to appear. In one of the earliest, from Leuna

near the Saale River, a man was laid in a carefully

constructed wooden chamber with a collection of

fine Roman pottery, glassware and metalware, and

three silver arrowheads. He also wore spurs; in a

nearby pit was found the skull and lower-leg bones

of a horse.

In the following century, graves deriving from

and often embellishing upon this new funerary

model spread through the Germanic regions within

and without the Roman frontier along the Rhine,

with many of them found in the Frankish territories.

Its basic elements are inhumation; burial wearing

everyday dress, as indicated by such items as belt

buckles; and a funerary deposit consisting of pottery

and perhaps glassware and metalware of Roman

manufacture, distinctive brooches, and sometimes

other personal ornaments in female graves and

weapons in many male graves. These weapons

might consist of a single spear or axe, but the richest

graves might include a panoply (a group of weap-

ons), including a sword and a shield. In about

A.D.

350 such graves appear in significant numbers at

Roman military sites, such as Krefeld-Gellep and

Rhenen on the Rhine frontier, but they also turn up

in a variety of funerary contexts across northern

Gaul, far from places of Germanic settlement.

Hörst-Wolfgang Böhme, Périn, and other re-

searchers have argued that that these new funerary

customs reflect the militarization of the late Roman

Empire, a process that drew heavily upon barbarian,

and particularly German, manpower. Sometimes

this “conscription” was done by force: Constantine

settled defeated Frankish groups as a kind of half-

free militia (laeti) on lands they could farm in return

for hereditary military service. Other Franks freely

enlisted; Frankish units are known in the Notitia

Dignitatum, a muster roll of Roman forces from c.

A.D. 400. By that time some Franks, such as Silvanus

and Arbogast, held the highest commands: they

have been called “imperial Germans.” This military

service surely encouraged a sense of complex identi-

ty: a funerary inscription in Pannonia proudly iden-

tifies its author as both a Frank and Roman soldier.

Valor in war always had been the supreme Ger-

man virtue; the late Roman world provided many

more opportunities to make it the route to high sta-

tus and success. The grave of a military leader buried

outside the town of Vermand, in northern Gaul,

with his helmet, his display of weapons, and his fine

tableware, vividly reflects the material success of one

such soldier. It also hints at a double allegiance: to

the Roman world he served and to the new military

elite, Germanic by the choice of this funerary tradi-

tion, to which he belonged. Small cemeteries of bar-

barian graves from the Namur region (Haillot) to

the Somme (Vron) reflect the settling of these

Germanic groups within the empire and their de-

fending it.

The complicated events of the fifth century,

which led to the breakup of the Roman Empire in

the west, served to consolidate this new sense of

Frankish identity. Unlike such barbarian peoples as

the Huns, sweeping in from the Asian steppes, or

the Visigoths, fleeing and fighting and plundering

over forty years from the Danube to Italy to end in

southwest Gaul in

A.D. 418, the Franks had no vast

migration to make. Already well established in their

homeland, straddling the Lower Rhine frontier and

divided into competing groups, their leaders might

have expanded their power opportunistically as cir-

cumstances permitted or might have had it fall into

their hands. The small garrison occupying the fort

of Vireux-Moulin, overlooking the Meuse, be-

tween about

A.D. 370 and 450 is a symbol of this

relative stability in a changing world. It is significant

that they maintained the furnished burial traditions

when these customs already had disappeared in the

more Romanized regions south and west.

In 451 some Frankish forces helped Aetius halt

the Hunnic invasion of Gaul; it is at about this time

that the lineage of Childeric became established in

the fortified town of Tournai (Belgium). After his

death, his son Clovis defeated the last Roman com-

MEROVINGIAN FRANKS

ANCIENT EUROPE

399

mander in northern Gaul (A.D. 486), thus launching

a career of successful aggression that would leave

him, at his death in 511, master of three-fourths of

Gaul, from the Pyrenees to the Rhine. Having

wiped out the competing Frankish reiks lineages, he

had become the founder of the Merovingian dynas-

ty. Clovis took two other highly significant steps in

the shaping of the Frankish identity. He converted

to the Catholic faith, thus opening the way to an en-

during alliance between the king and the Gallic

church. He also made his capital in Paris, deep in

the heart of Romanized Gaul and far from the origi-

nal Frankish homelands.

Perhaps the most striking archaeological reflec-

tion of the reign of Clovis is the revival of the weap-

ons- and ornament-furnished burial traditions and

their spread into new regions. Only in the core

Frankish regions between the Somme and Rhine

did weapons burial continue in the fifth century, an

indication that among the Franks it had taken hold

as a marker of cultural identity. After the middle of

the fifth century, it derived new life from “Danubian

influences,” such as the colorful gold-and-garnet

jewelry style that appears in Pouan and Airan in

Gaul. Childeric’s grave, whose discovery in 1653

marks the beginning of Merovingian archaeology,

was a spectacular restatement of the elite furnished

burial.

The many chieftains’ graves of the “Flonheim-

Gültlingen” type of the late fifth century and early

sixth century reflect a greater standardization of the

elite burial model. This is particularly notable in the

case of the weapons panoply: a long sword, a kind

of harpoon called an angon, one or more lances, ar-

rows, a shield, a curved throwing axe, and a short

one-edged stabbing sword called a scramasax. The

axe was given the name francisca and was described

by the mid-sixth century Byzantine writer Agathias

as a typical Frankish weapon. Bright polychrome

gold cloisonné ornament, which might decorate

sword hilts or scabbards, belt buckles or brooches,

also are typical of this elite model. Such graves ap-

pear as the focal point of new burial groups in estab-

lished cemeteries, such as Krefeld-Gellep and

Rhenen along the Lower Rhine, or as the starting

point of new cemeteries, such as Charleville-

Mézières or Lavoye, which reflect expanding Mero-

vingian power under Clovis and his sons.

The originality of this “Frankish funerary fa-

cies” is underlined by its spread throughout the

sixth century. Early archaeologists, among them

Édouard Salin, thought that funerary customs were

inherited from the distant tribal past and assumed

that the other barbarian peoples in Gaul, the Bur-

gundians and the Visigoths, would have their own

distinct rites and artifacts. Neither of these groups,

however, developed an archaeologically recogniz-

able set of funerary customs, at least before they had

been absorbed into the Merovingian kingdom.

Cemeteries such as Herpes and Biron in Aquitaine

or Brèves and Charnay in Burgundy now are identi-

fied either with Frankish groups who had come to

hold territory in the conquered areas or with local

groups eager to adopt the customs of the victors.

The former case has been argued at Bâle-

Bernerring, in Switzerland, where the leading fig-

ures were buried in elaborate funerary chambers

under mounds, as it is now known that Childeric

had been in Tournai. The latter interpretation has

been proposed at Frénouville, in lower Normandy,

a site that was excavated by the Centre de Recher-

ches d’Archéologie Médiévale of the University of

Caen in the 1960s and 1970s. There were distinct

late Roman and Merovingian zones in this ceme-

tery, marked by different grave orientations and fu-

nerary practices. Still a comprehensive anthropolog-

ical analysis of the skeletal material, the most

thorough and rigorous yet to be completed for any

French site, indicates that it is the same population.

This suggests that this sixth-century community in

the remote Gallic northwest was adopting the vo-

cabulary of new funerary custom to say, in a distort-

ed echo of the Pannonian inscription cited earlier,

we are Gallo-Romans and Merovingians, too.

The reign of Clovis also saw the rise of the so-

called Salic Law, which, like the codes of the Bur-

gundians and the Visigoths and the parallel codes of

the latter groups for their Roman subjects, marks

the crystallization of ethnic consciousness. Even

after these areas, the Burgundian and Visigothic

Kingdoms, roughly modern southeastern and

southwestern France, were conquered by the Franks

(Aquitaine in

A.D. 507 and Burgundian kingdom

[Burgondie] in

A.D. 536) the principle of the “per-

sonality of law” was long maintained; indeed in the

seventh century a new law code was promulgated

for the Rhenish Franks around Cologne. Gregory of

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

400

ANCIENT EUROPE