Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

that they would continue on their eastward journey

back to Switzerland.

The path of migration appears to have first tra-

versed the Alps along the western side of the Italian

Peninsula but was soon expanded to include routes

south from Bohemia. A delegation of Galatian Celts

met Alexander the Great on the banks of the Dan-

ube during his campaign in the Balkans in 335

B.C.

The source is Ptolemy I, later the ruler of Egypt,

who was present on the occasion. Celtic incursion

into Thrace, Macedonia, and Greece in about 280

B.C. was the culmination of frequent movements of

war parties that had begun nearly a century earlier.

Delphi was attacked around 279

B.C. by Brennos,

who led his warriors to the temple of the Oracle,

which they burned. There is no evidence for Celtic

resettlement in Greece, and artifacts associated with

the assault on Delphi are few.

Classical sources settled upon various accounts

to explain why Celts left their homeland and jour-

neyed south through Alpine passes to establish

communities in Italy and Asia Minor. A report by

Livy states, “There is a tradition that it was the lure

of Italian fruits and especially of wine, a pleasure

then new to them, that drew the Gauls to cross the

Alps and settle in regions previously cultivated by

the Etruscans.” The Greek scholar Dionysius of

Halicarnassus elaborates on this sequence of events,

saying that the Gauls were enticed to Italy with

wine, olive oil, and figs and were told that the place

was occupied by men who fought like women and

would offer no real resistance. According to these

two authors, the quality of life available on the Ital-

ian Peninsula attracted Celtic immigrants. In anoth-

er version, the Greek geographer Strabo reports

that tribes joined forces in pursuit of plunder. A fur-

ther account says that population stress prompted

consultation with the gods who directed one broth-

er to take his followers to the Hercynian uplands in

southern Germany while the other was told to take

the more pleasant road into Italy. Scholarly analysis

suggests that population growth was a contributing

factor, along with a deteriorating climatic phase.

These conditions, combined with the disruptions in

the traffic of Mediterranean imports that followed

the establishment of Roman colonies competing

with the Greek trading post at Massalia, may indeed

have been sufficient cause.

It is probable that the migration that began in

the Champagne region was motivated by a desire to

acquire luxury goods and wine and that it was car-

ried out by young adult males of the warrior aristoc-

racy, as the archaeological evidence indicates. How-

ever, movements such as that of the Helvetii

included men, women, and children, and they were

most likely motivated by other factors that included

hardship.

Migration contributed greatly to restructuring

Celtic society. Large numbers of Celts were intro-

duced to different lifestyles in the various Mediter-

ranean civilizations. When they returned to their

homes north of the Alps (and many of them did)

they brought back coinage and an appreciation of

its use. They also transported ideas, technologies,

and objects that they acquired, along with contacts

that enabled them to enter into new trade relation-

ships. Further, the process of migration itself had

temporarily reorganized tribal units. During migra-

tion, loose coalitions of otherwise distinct groups

formed under the leadership of single individuals.

Post-migration Celtic Europe during the proto-

urban oppida phase (150–50

B.C.) reflects these eco-

nomic and social transformations.

See also Celts (vol. 2, part 6); La Tène (vol. 2, part 6); La

Tène Art (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnold, Bettina, and D. Blair Gibson, eds. Celtic Chiefdom,

Celtic State: The Evolution of Complex Social Systems in

Prehistoric Europe. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1995.

Cunliffe, Barry. Greeks, Romans, and Barbarians: Spheres of

Interaction. New York: Methuen, 1988.

Kristiansen, Kristian. Europe before History. Cambridge,

U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Livy. The Early History of Rome: Books I–V of the History of

Rome from Its Foundation. Translated by Aubrey de

Selincourt. Baltimore, Md.: Penguin, 1965.

Moscati, Sabatino, et al., eds. The Celts. New York: Rizzoli,

1991.

Wells, Peter S. The Barbarians Speak. Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1999.

S

USAN MALIN-BOYCE

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

150

ANCIENT EUROPE

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

GERMANS

■

The question of the identity of the peoples who

were first called Germans is immensely complex.

Three main approaches to the subject are historical,

archaeological, and linguistic.

HISTORICAL

The earliest description of peoples called Germans

is in Julius Caesar’s commentary about his military

campaigns in Gaul between 58 and 51

B.C. Caesar’s

remarks formed the basis for later Roman use of the

name and thus for subsequent medieval and mod-

ern applications. Any discussion of the identity of

the early Germans must begin with Caesar. The

Greek writer Posidonius (135–51

B.C.) may have

mentioned peoples he called Germans, but his

works do not survive.

Two assertions by Caesar are of particular im-

portance. One is that the peoples east of the Rhine

were Germans, whereas those west of the river were

Gauls (whom ancient Greek writers called Celts).

The other is that the Germans had a less complex

society than did the Gauls. Unlike the Gauls, the

Germans had no towns, little agriculture, and less-

developed religious rituals, and they spent much of

their time hunting and fighting. From Caesar on-

ward, Roman writers called the peoples east of the

Rhine and north of the Upper Danube Germans. It

is not known what these groups called themselves.

It is very unlikely that they thought of themselves

as any kind of single people, at least before many of

them united to face the threat of Roman conquest.

In his work known as the Germania, published

in

A.D. 98, the Roman historian Tacitus described

in greater detail the peoples whom Caesar had

called Germans. From the second half of the six-

teenth century, when the manuscript of his writing

was rediscovered and translated, the account of Tac-

itus formed the basis for many studies of the early

Germans. Much of his description was applied even

to groups who lived many centuries after the peo-

ples he called Germans. Well into modern times,

scholars interpreted his work as if it were an ethno-

graphic account of peoples in northern Europe be-

yond the Roman frontier.

Approaches to the writings of Caesar and Taci-

tus have become more critical. Many historians be-

lieve that Caesar’s assertions that the peoples east of

the Rhine were Germans was politically motivated,

to portray the Rhine as a border between Gauls and

Germans and thus a cultural frontier at the eastern

edge of peoples whom he was fighting to conquer.

Much of Caesar’s description of the Germans as a

simpler people than the Gauls may have been based

on long-held Roman ideas about the geography and

the peoples of northern Europe. Caesar had little di-

rect contact with groups east of the Rhine, and his

remarks about them were made in the context of his

primary concern, which was the conquest of Gaul.

A century of critical study of Tacitus has led to

the conclusion that his Germania should be ap-

proached primarily as a literary work, rather than an

ethnographic one. Many believe that his descrip-

tions of the Germans tell more about Roman atti-

tudes and values than about the peoples of northern

Europe. Whereas Roman writers, following Caesar

and Tacitus, regarded Germans and Gauls as dis-

ANCIENT EUROPE

151

tinct peoples, Greek authors, such as Strabo and

Cassius Dio, considered them part of the larger

group of peoples whom they called Celts. Later

Roman and medieval writers built upon the tradi-

tions of their predecessors, classifying many peoples

identified in later centuries—such as Burgundians,

Franks, Goths, and Langobards—as Germans.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL

The archaeological evidence shows a much more

complex situation than Caesar and Tacitus describe.

When Caesar was writing, between 58 and 51

B.C.,

the peoples east of the upper and middle Rhine were

very much like those west of the Rhine against

whom Caesar was fighting. Large fortified towns

known as oppida dominated the landscape. As at the

oppida in Gaul, the archaeology shows complex

economic and political organization, with mass pro-

duction of pottery and iron tools, minting of coins,

and long-distance trade with much of Europe, in-

cluding Roman Italy. East of the lower Rhine, how-

ever, the archaeology indicates a different kind of

society, without the large oppida and with smaller-

scale manufacturing and commerce. In this region

Caesar’s assertion about lack of towns corresponds

to the archaeological evidence, but his statements

about undeveloped agriculture and the major role

of hunting are proved wrong by the archaeology.

Intensive farming and livestock husbandry had been

practiced in the region for some four thousand years

before Caesar’s time.

The style of material culture, especially metal

ornaments and pottery, in much of the region east

of the lower Rhine is known as Jastorf, and it con-

trasts with the La Tène style characteristic to the

south and west. Earlier archaeologists have linked

La Tène style with Celts (Gauls) and Jastorf style

with Germans, but studies show that such direct

connections between styles and peoples named by

Roman and Greek writers are unwarranted.

Throughout the Roman period (50

B.C. to A.D.

450), the archaeology shows regular interactions—

some peaceful, some violent—between the Roman

provinces west of the Rhine and the unconquered

lands to the east. Many graves east of the Rhine con-

tain fine products of Roman manufacturing, such as

pottery, bronze vessels, ornaments, and even weap-

ons. Such settlements as Feddersen Wierde in

Lower Saxony show that trade with the Roman

world brought both wealth and social change to

communities in these regions.

LINGUISTIC

The category “Germanic” as it applies to language

is difficult to investigate before the time of the

Roman conquests because the Iron Age peoples did

not leave writings. Roman and Greek observers did

not use language as a criterion in distinguishing the

peoples of northern Europe, probably because they

did not know enough about the native languages.

When runes were developed in northern parts of the

continent (by people familiar with Latin), probably

in the first or second century

A.D., they indicate the

presence of a well-developed language that linguists

classify as Germanic.

In the Rhineland, where many inscriptions sur-

vive from after the Roman conquest, some names

can be linked with Germanic and others with Celtic

languages. Certain names even combine elements of

the two linguistic traditions. Probably in much of

temperate Europe at the time of Caesar and Tacitus,

many people spoke languages that could not be

classified easily as either Germanic or Celtic today

but that included elements associated with both of

those categories.

See also Oppida (vol. 2, part 6); Manching (vol. 2, part

6); Gergovia (vol. 2, part 6); Kelheim (vol. 2, part

6); Langobards (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bazelmans, Jos. “Conceptualising Early Germanic Political

Structure.” In Images of the Past: Studies on Ancient So-

cieties in Northwestern Europe. Edited by N. Roymans

and F. Theuws, pp. 91–129. Amsterdam: University of

Amsterdam, 1991.

Beck, Heinrich, ed. Germanenprobleme in heutiger Sicht.

Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999.

Beck, Heinrich, Heiko Steuer, and Dieter Timpe, eds. Ger-

manen, Germania, Germanische Altertumskunde. Ber-

lin: Walter de Gruyter, 1998.

Lund, Allan A. Die ersten Germanen: Ethnizität und Ethno-

genese. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1998.

Pohl, Walter. Die Germanen. Munich: R. Oldenbourg,

2000.

Todd, Malcolm. The Early Germans. Oxford: Blackwell,

1992.

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

152

ANCIENT EUROPE

Wells, Peter S. Beyond Celts, Germans, and Scythians: Ar-

chaeology and Identity in Iron Age Europe. London:

Duckworth, 2001.

P

ETER S. WELLS

GERMANS

ANCIENT EUROPE

153

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

OPPIDA

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Manching . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

■

Oppidum is the Latin word for a defended site,

often with urban characteristics, and so, by exten-

sion, simply a “town.” The modern archaeological

usage is based on Julius Caesar’s De bello Gallico, in

which he terms the native urban settlements, such

as Genava (Geneva), Vesontio (Besançon), Lutetia

(Paris), Bibracte (Mont Beuvray), and Gergovia

(Gergovie), oppida, although he occasionally calls

them urbs (city). German and British nomenclature

thus uses this word for archaeological sites similar to

these historical towns—defended Late Iron Age

sites of the second to first centuries

B.C. of at least

25–30 hectares, which are found from the Hun-

garian plain to western France as well as in central

Spain. Caesar and other Latin authors also use

the term to describe hillforts and small defended

urban sites of 5–10 hectares; French nomenclature

follows this usage for the towns of southern France,

such as Entremont and Ensérune, and the sixth-

century Hallstatt hillforts, such as Mont Lassois

and the Heuneburg. In Britain the term is used

mainly for very large lowland settlements of the first

centuries

B.C. and A.D., such as Camulodunum

(Colchester), which can be as large as 2,000 hect-

ares, defined by linear dikes. In this discussion the

British and German nomenclature is used. This

essay will discuss oppida in Gaul, central Europe,

and Britain.

OPPIDA IN GAUL AND

CENTRAL EUROPE

Because of their large size and no doubt large popu-

lations, the oppida must belong to a very different

sort of political entity from that of the Mediterra-

nean city-states, or what might be termed tribal

states. They bear the name of a tribe rather than of

a major town (e.g., the Aedui and the Arverni, com-

pared with the Romans and Athenians). Where the

territorial size of the state is known, they tend to be

much larger than the city-states. Mont Beuvray near

Autun in Burgundy is a good type site. First, Caesar

names it as the ancient Bibracte, chief town of the

Aedui, who were legal allies of the Romans from at

least the second century

B.C. Caesar, who spent the

winter of 52–51

B.C. in the town writing De bello

Gallico, tells a little about the state’s oligarchic con-

stitution. He mentions the annual election of the

chief magistrate (the vergobret), the existence of an

assembly (senatus), and the sources of the state’s in-

come (e.g., the annual auctioning of the right to

collect tolls from traders).

Mont Beuvray lies in a good defensive position

on a hilltop that dominates the Morvan mountain

range, and it is visible from a considerable distance

in all directions. Although the immediate area is ag-

riculturally poor, there are raw resources, such as

iron ore, and the oppidum controlled one of the

154

ANCIENT EUROPE

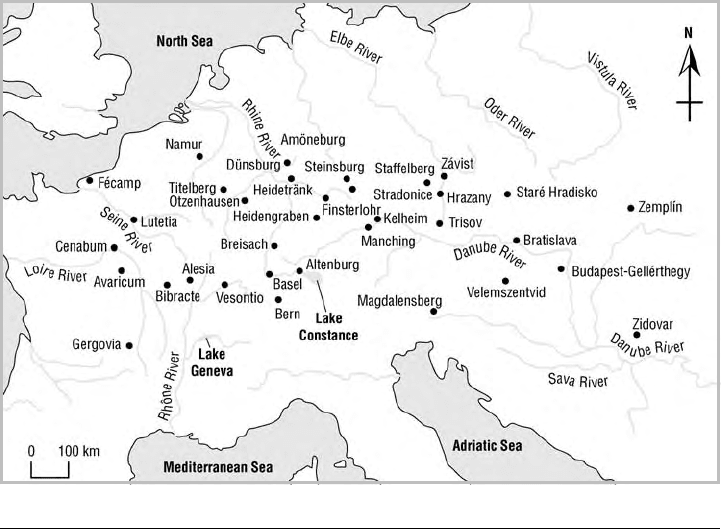

Some of the principal oppida in Europe. ADAPTED FROM WELLS 1999.

major routes from the Mediterranean to the Atlan-

tic, from the valley of the Saône into the Paris Basin

via the River Yonne. Dendrochronological evidence

shows that the oppidum was founded about 120

B.C.

and initially was surrounded by a rampart low on the

hill, enclosing some 200 hectares. This was a murus

Gallicus, as described by Caesar, a wall revetted

front and back by stone walls and with an internal

timber lacing joined with iron spikes where the

balks cross. In a murus Gallicus the space between

the walls is filled with earth and stones, and there is

an earthen ramp behind and a ditch (or, in the case

of Mont Beuvray, a terrace) in front. Somewhat

later the site was reduced in size to 135 hectares

with a new murus Gallicus rampart, which was re-

paired regularly, and, finally, in the later first century

B.C. by a Fécamp rampart—a massive bank of earth

with a sloping glacis front (named by Mortimer

Wheeler who dug the oppidum overlooking the

modern-day town of Fécamp). The reason for this

series of alterations may have been to make the ram-

parts more visible from a distance. Certainly, de-

fense is not the only purpose of the “defenses”—the

main gate, the Porte de Rebout, is much wider than

would be needed for defense, and there is no elabo-

rate gatehouse such as those known from many

other sites.

The site was a major center for consumption—

the annual influx of wine amphorae from western

Italy must be numbered in the thousands, but the

pre-conquest deposits at Mont Beuvray are poorly

known, as they are overlain by masonry buildings of

the Augustan period. The site saw a massive invest-

ment in public and private buildings in the two gen-

erations following the conquest, before the pop-

ulation moved to a less-exposed site 20 kilo-

meters away at Augustodunum (Autun) c. 10

B.C.

to

A.D. 10.

Several major excavations of oppida reveal their

internal organization and the range of buildings—

Villeneuve–St. Germain near Soissons and Condé-

sur-Suippe/Variscourt in France; Staré Hradisko,

Hrazany, and Závist in the Czech Republic; and

Manching on the Danube in Germany. All of them

have produced large palisaded enclosures, which

have the appearance of farmsteads, usually with a

large timber house and ancillary barns, stables, gra-

naries, workshops, and wells. The largest enclosures

are up to 4,000 square meters, but more typically

they are about 1,000 to 2,000 square meters. They

seem to be elite residences, the equivalent of the

courtyard house in the Mediterranean world. They

also commonly have evidence of industrial activities,

OPPIDA

ANCIENT EUROPE

155

such as bronze casting, ironsmithing, and coin man-

ufacture.

The lower classes lived in smaller timber build-

ings, typically with a single room, constructed on ar-

tificial terraces on hill slopes, or, in the case of Mont

Beuvray and Manching, lined along the main thor-

oughfares. Many people of this class were engaged

in manufacturing. Some were bronzesmiths, mak-

ing such mass-produced items as safety-pin brooch-

es and belt fittings. Others were ironworkers, pro-

ducing such weapons as swords, iron scabbards,

spears, and shield bosses; a wide range of tools for

carpentry (drills, hammers, chisels, knives, axes); ag-

ricultural equipment (plowshares, sickles, scythes,

pruning hooks); house fittings (latch lifters, keys,

locks, cauldron hangers), or vehicle fittings for char-

iots and wagons. Glass was worked to produce mul-

ticolored beads, pendants, and bracelets or red glass

as an overlay on decorative studs. Wool was spun

and woven into textiles, and leather was worked, al-

though little survives of the products themselves. A

great range of pottery was made, from basic cooking

pots and eating vessels to elaborate painted vessels

with geometric and zoomorphic (based on animal

forms) decorations. Individual pots, such as special-

ist cooking pots made of clay containing graphite,

could be traded over several hundred kilometers.

Thus, oppida were important centers of manufac-

ture, linked together by extensive trade networks

that saw trade not only in finished goods but also

in raw materials, such as metals, salt (Hallstatt, Bad

Nauheim), amber, or shale for bracelets and vessels.

In some cases, such as Kelheim in Germany and

Titelberg in Luxembourg, the oppidum encloses or

sits on the raw material (in both these cases, iron

ores).

Oppida were deliberate foundations, formed at

a specific moment in time when the decision was

made to found a town and for the population to

move in. It implies preexisting knowledge of what

a town is like and the necessary economic, social,

and political superstructure to support it. Manching

is a unique example of a settlement that gradually

increased in size until it achieved urban proportions

and was given defenses. Lezoux in central France

presents the more normal sequence: an open settle-

ment of about 8 hectares in the plain, which was

abandoned at the end of the second century

B.C. for

a defended oppidum on a nearby hill. This site, in

turn, was abandoned in the late first century

B.C. for

a Roman town at the foot of the hill.

There are considerable regional variations,

however. Sometimes a series of oppida replace one

another—Villeneuve–St. Germain and Pommiers at

Soissons or Corent, Gondole, and Gergovie at Cler-

mont-Ferrand. In many cases, no preceding major

settlement is known, and the urban site may repre-

sent some sort of synoicism, or joining together into

one community, of numerous small settlements. At

Roanne and Feurs the early open settlements de-

creased in size when the nearby oppida of Jœvres,

Crêt-Châtelard, and Palais d’Essalois were estab-

lished, but neither site was abandoned and, unlike

the local oppida, developed into flourishing Roman

towns. In some areas, such as Clermont-Ferrand,

virtually all the preceding settlements disappeared.

In others, such as Champagne, there were many

small farms and hamlets in the countryside; indeed,

the distribution of rich burials suggests that in

northern France this was where many of the elite re-

sided. In still other areas, especially in southeastern

France, oppida are rare or unknown, and open set-

tlements, such as Saumeray, in the territory of the

Carnutes could continue unaffected by the founda-

tion of oppida not far away. Oppida also could be

founded but never attract any permanent occupa-

tion.

In Gaul the main period for the foundation of

the oppida (on the evidence of dendrochronology)

is about 120

B.C. This was around the time of the

Roman takeover of southern France (125–123

B.C.)

and the defeat in 123

B.C. of the Arverni, who, ac-

cording to the Greek ethnographer Posidonius, had

controlled an area from the Atlantic to the Rhine.

In central Europe (e.g., the Czech Republic) such

sites as Hrazany, Závist, and Staré Hradisko go back

a couple of generations earlier, to the early second

century

B.C., but there is no historical context for

their foundation.

The oppida played a major role in the events of

Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, of which the sieges of

Avaricum (Bourges), Gergovia, Alesia (Alise–Ste.

Reine), and Uxellodunum (Puy-d’Issolud) are the

most spectacular. In contrast, when the Romans

reached the Danube in 15–14

B.C. many sites, such

as Manching, seem to have been abandoned. The

gates of Hrazany and Závist, outside the area con-

quered by the Romans, were hastily blocked just be-

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

156

ANCIENT EUROPE

fore they were burned down. This event traditional-

ly has been associated with the rise of the Germanic

chieftain Maroboduus and the Marcomanni c. 10

B.C., but the archaeological dating now suggests an

earlier date for their destruction. In contrast, many

of the sites in Gaul, even in areas hostile to Rome,

continued in occupation for at least a couple of gen-

erations (Gergovie, Mont Beuvray), if not through-

out the Roman period (Alise–Ste. Reine). Indeed,

many sites can claim continuity of occupation to the

present day, among them Besançon (Vesontio),

Reims (Durocortorum), Paris, Chartres (Au-

tricum), and Orléans (Aurelianum Cenabum).

The sites in central Spain are less well known

and studied; they contrast with the generally smaller

Iberian towns of the east and south and the hillforts

of the western and northern Iberian Peninsula.

Their histories are longer than those of temperate

Europe, with sites such as Las Cogotas and La Mesa

de Miranda (Ávila) starting as early as the fifth cen-

tury

B.C. A small number of sites figure in the Car-

thaginian and Roman conflicts: Salamanca (Sala-

mantica) was captured by the Carthaginian general

Hannibal in 220

B.C., and Numantia near Soria was

the scene of a siege by the Roman general Scipio Af-

ricanus in 133

B.C. Typically, these sites consist of

two or three defended enclosures with elaborate en-

trances and large enclosure areas (e.g., La Mesa de

Miranda, at 30 hectares; Las Cogotas, at 14.5 hect-

ares; and Ulaca, at 80 hectares). The latter site con-

tains many small stone and double houses, usually

with a single room but occasionally with three or

four rooms, but there are also ceremonial and reli-

gious structures. The associated cemeteries contain

some rich burials with weapons and fine bronze jew-

elry, but the very rich aristocratic burials found in

northern Gaul generally are absent, suggesting a less

hierarchical society.

OPPIDA IN BRITAIN

The oppida of Britain date to the late first century

B.C. and early first century A.D. and are confined to

the south and east of the country. Generally, they

are in low-lying areas enclosing valleys or low ridges

between rivers, suggesting that their role was not

primarily defensive. In fact, their huge size (300 to

2,000 hectares or more) would have been impossi-

ble to man. The linear earthworks, or dikes, even

avoid commanding strategic positions, and al-

though they are often massive, with sometimes dou-

ble or triple lines of ramparts, their function seems

rather to impress. They may mark royal properties,

and only parts of them were occupied. The richest

Late Iron Age burials are associated with them—

Lexden at Colchester and Folly Lane at St. Albans.

Historical sources and coinage allow researchers to

identify up to three generations of dynastic kings,

whose names appear on the coins along with the

names of the cities, Camulodunum (Colchester),

Verulamium (St. Albans), and Calleva Atrebatum

(Silchester). Classical sources call Colchester the

“capital” of Cunobelin (Cunobelinus, or Cymbe-

line), “king of the Britons.” All the sites produce ev-

idence of extensive trade with the Roman world,

with wine and fish paste (garum) from Italy and

Spain and fine pottery from Gaul and northern

Italy. Several developed into major Roman towns.

See also Germans (vol. 2, part 6); Manching (vol. 2, part

6); Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6); Gergovia (vol. 2, part

6); Kelheim (vol. 2, part 6); The Heuneburg (vol. 2,

part 6); Agriculture (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Collis, John R. Oppida: Earliest Towns North of the Alps.

Sheffield, U.K.: University of Sheffield, 1984.

Cunliffe, Barry W. Iron Age Communities in Britain: An Ac-

count of England, Scotland, and Wales from the Seventh

Century

BC until the Roman Conquest. 3d ed. London:

Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1991.

Cunliffe, Barry W., and Simon Keay. Social Complexity and

the Development of Towns in Iberia, from the Copper Age

to the Second Century

AD. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1995.

Fichtl, S. La ville celtique: Les oppida de 150 av. J.-C. à 15

ap. J.-C. Paris: Éditions Errance, 2000.

Hodges, Richard. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns

and Trade

A.D. 600–1000. 2d ed. London: Duckworth,

1989.

Guichard, Vincent, and Franck Perrin, eds. L’aristocratie

celte à la fin de l’Âge du Fer. Bibracte 4. Glux-en-

Glenne, France: Centre archéologique européenne du

Mont Beuvray, 2001.

Guichard, Vincent, S. Sievers, and O. H. Urban, eds. Les

processus d’urbanisation à l’âge du Fer: Eisenzeitliche

Urbanisationsprozesse. Bibracte 5. Glux-en-Glenne,

France: Centre archéologique européenne du Mont

Beuvray, 2000.

Wells, Peter S. The Barbarians Speak. Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 1999.

J

OHN COLLIS

OPPIDA

ANCIENT EUROPE

157

■

MANCHING

Manching is a La Tène period oppidum site in Ba-

varia, Germany, dated from about 250 to 80

B.C.,

after which time it gradually was abandoned. It is

one of a handful of sites of its type that have been

investigated systematically, although because of its

enormity, only about 3 percent of the settlement

has been excavated. It has yielded both cultural ma-

terial and physical settlement data that inform pre-

historians about the organization and function of an

oppidum. Oppidum (plural, oppida) is the term that

Julius Caesar used to describe large, fortified towns

that may have served as administrative centers for

the Gallic tribes he had come north to conquer be-

tween 58 and 50

B.C.

The role of oppida is debated in the archaeolog-

ical literature mainly because of the structural vari-

ability among these settlements, which differ from

one another primarily in internal organization.

Criteria for identification are based on settlement

size, presence of fortification, industrial activities,

geographic position, and period of occupation.

Generally, the sites are large (hundreds of hectares)

and defensively enclosed by earth and timber walls

that use ditch and rampart technology. Such sites

were located on naturally defended or elevated

landscape features that intersected trade routes.

They included areas for intensive production of iron

implements and pottery. Oppida were established

and abandoned during the final two centuries

B.C.,

and their distribution across Europe coincides with

the occupation of territories by Celtic populations

from western France to the Czech Republic.

Manching is exceptional both for the scale of ar-

chaeological investigation that has focused on the

site and for the wealth and diversity of material evi-

dence collected there. Just south of Ingolstadt in

the county of Pfaffenhoffen, this 380-hectare site

once was situated on a river terrace along the Dan-

ube. The unusual setting (most oppida are elevated)

was compensated for by its encroachment on a

swamp along its northeast side. The supplemental

fortification constructed around the exposed por-

tion of the settlement is a 7.2-kilometer-long ram-

part wall of the murus Gallicus type. Muri Gallici—

timber-laced ramparts fronted by ditches—

generally are not seen as far east as Manching. The

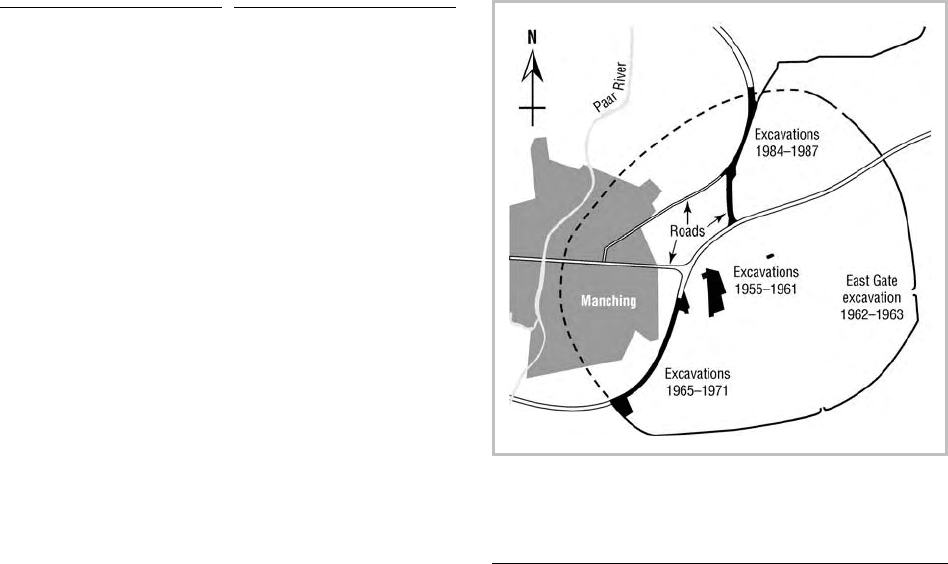

Fig. 1. Site plan showing excavation areas (dark regions) at

modern-day Manching, Bavaria. Dark segments of modern

roadways show excavation areas necessitated by roadway

construction. ADAPTED FROM MOSCATI ET AL. 1991.

Kelheim-type rampart, with its exterior face con-

structed of vertical timbers and drystone wall (there

is no interior walling or timber lacing through the

earthen ramp), is more common throughout this

area. The site was known from the remains of the

wall from the early nineteenth century but was mis-

taken for a construction of Roman origin and iden-

tified only tentatively as Celtic in 1888 by a Roman-

ist familiar with Caesar’s De bello Gallico. In 1903

Paul Reinecke, working on an inventory of monu-

ments and historic places, recognized artifacts from

Manching that were similar to finds from oppida in

France and Bohemia.

Excavations at Manching have been necessitat-

ed by construction projects that started with a mili-

tary airfield between 1936 and 1938. A central por-

tion of the settlement was destroyed when

mechanical equipment was used to strip the area

and tear away part of the wall. Efforts to recover ar-

tifacts were restricted by the exigencies of impend-

ing war, and only those materials that could be res-

cued from the spoil piles were saved. Subsequently,

the airfield was bombed. In 1955 Allied forces de-

cided to rebuild the airfield and, following negotia-

tions with archaeologists, contributed an unprece-

dented sum of money for investigation of the

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

158

ANCIENT EUROPE

settlement and of the area that would be affected by

renewed construction. Excavation began that year

and continued until 1974 under the direction of

Werner Krämer. A subsequent excavation was orga-

nized in 1984, following a ten-year hiatus, through

the Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (the

Bavarian department that oversees protection of

cultural sites and monuments). This investigation

responded to the planned construction of an exit

ramp on the secondary roadway that passes through

the site (Landstrasse B16) and focused on a previ-

ously unexplored tract in the northern part of the

settlement. Approximately 1 kilometer long by

35–60 meters wide, a strip running from the center

of the roughly circular enclosed area to the wall was

examined. A further 6-hectare excavation was

begun in 1996. Materials in all these campaigns are

consistent with La Tène C1 (280–220

B.C.)

through D1 (120–80

B.C.) dates.

Evidence for development of the site shows a

multiphase sequence of settlement beginning as

early as the third century

B.C., making Manching

one of the older oppida. The earliest settlement is

concentrated toward the center of the enclosed area

and predates the construction of the wall. A track

oriented east-west runs through the old center and

provided the foundation for a later main street link-

ing the east and west gates of the murus Gallicus.

It is likely that the initial construction of the

wall (second half of the second century

B.C.) was an

expression of prestige that established Manching as

a focal point for activities centered on production

and exchange. These activities encompassed not

only collection of raw materials and manufacture of

goods but also feasting and the functions associated

with market towns and fairs. The wall itself was re-

built during the occupation of Manching, as is evi-

denced by a dendrochronological date for a struc-

ture in front of the eastern gate that coincides with

its renovation in 105

B.C. It is likely that the func-

tion of the wall changed through time from display

to defense because a third stage of construction re-

inforces the entire 7.2-kilometer length of the en-

closure. Furthermore, burials of individuals who

died of battle injuries attest to an attack on the set-

tlement.

The interior of the settlement seems to have

been organized to facilitate trade. Structures in-

clude rows of stalls, homes, and even warehouses for

the agricultural produce that made up the bulk of

exchanged goods. Raw materials used in the pro-

duction of glass, pottery, iron, and bronze indicate

that Manching was a thriving center for craft pro-

ducers. Coins were recovered from the settlement,

as were strikes used to mint coinage. Forty-eight

imported amphorae that contained Mediterranean

wine during transportation are among the items

that were traded. Published volumes covering the

analysis of the Manching materials feature bronze

finds, tools, fibulae, glass, faunal material, graphite

pottery, imported pottery and coarse wares, smooth

wheel-thrown pottery and painted pottery, and

human burials associated with the settlement.

See also La Tène (vol. 2, part 6); Oppida (vol. 2, part 6);

Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bott, R. D., G. Grosse, F. E. Wagner, U. Wagner, R. Geb-

hard, and J. Riederer. “The Oppidum of Manching: A

Center of Celtic Culture in Early Europe.” Natur-

wissenschaften 81, no. 12 (1994): 560–562.

Collis, John. Oppida: Earliest Towns North of the Alps. Char-

lesworth, U.K.: H. Huddersfield, 1984.

Dannheimer, Hermann, and Rupert Gebhard, eds. Das

keltische Jahrtausend. Mainz, Germany: Philipp von

Zabern, 1993.

Gebhard, Rupert. “The Celtic Oppidum of Manching and

Its Exchange System.“ In Different Iron Ages: Studies

on the Iron Age in Temperate Europe. Edited by J. D.

Hill and C. G. Cumberpatch, pp. 111–120. BAR Inter-

national Series, no. 602. Oxford: British Archaeological

Reports, 1995.

Green, Miranda J., ed. The Celtic World. London: Rout-

ledge, 1995.

Krämer, Werner. “The Oppidum at Manching.” Antiquity

34 (1960): 191–200.

Moscati, Sabatino, et al., eds. The Celts. New York: Rizzoli,

1991.

Wells, Peter S. Farms, Villages, and Cities: Commerce and

Urban Origins in Late Prehistoric Europe. Ithaca, N.Y.:

Cornell University Press, 1984.

S

USAN MALIN-BOYCE

MANCHING

ANCIENT EUROPE

159