Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

HILLFORTS

■

Sites of physical eminence in the landscape have

been important throughout prehistory. Hilltops

may well have been liminal places where the world

of the living met the world of the supernatural,

where the dead were laid to rest in a sacred space.

They could have been locations for religious gather-

ings, perhaps at specific times of the year.

Hilltops also could have offered a measure of

short-term protection in uncertain times, but a lon-

ger-term threat would have called for defensive

building. Initially, wooden palisades might have

been sufficient, but soon more substantial structures

of earth or stone would have to have been built.

Many of these sites were never more than places of

temporary refuge. There is no doubt that in all areas

of Europe such defended enclosures were sites of

permanent occupation that often were associated

with industrial, commercial, and probably also ad-

ministrative and ritual activity. Security and defense

must be seen as the dominant function of hillforts,

but these frequently impressive constructions must

have served other, less material purposes. The great

sites—Maiden Castle in Dorset, England, as a prime

example—possess massive ramparts that appear far

larger and more elaborate than was dictated by the

needs of military defense. With these sites, consider-

ations of prestige and ostentation may be assumed.

Dominating the physical horizon, such great hill-

forts were tangible statements of tribal power.

It is not completely clear when hillforts in the

truest sense first were constructed in continental

Europe. As early as the late fifth and early fourth

millennia

B.C., simple palisaded enclosures were

elaborated by the erection of earthworks, often of

impressive dimensions, in ostensibly defensive situa-

tions. At least a few of them were for protection. In

Britain hilltop settlements of the Neolithic, such as

Carn Brea in Cornwall and Hambledon Hill in Dor-

set, suggest a similar function.

Early Bronze Age Europe saw continued, spo-

radic use of hilltop sites, especially in parts of Ger-

many and farther east, though these were a response

to local needs rather than a widespread develop-

ment. The evolution of hillfort construction on a

significant scale across Europe, however, com-

menced in the later Bronze Age, perhaps at the be-

ginning of the last pre-Christian millennium. There

has been considerable discussion concerning the

impetus for this trend: population pressure, climatic

deterioration, changing polities, security uncertain-

ties, and novel methods of warfare all have been

proposed. It is likely that all these factors played a

part in this trend to a greater or lesser extent, but

significant resources, in both materials and man-

power, clearly were involved in their creation.

Within the fortified area at this time, houses fre-

quently were situated along the ramparts or filling

much of the internal area in regular, parallel rows.

The Wittnauer Horn in Switzerland, a promontory

site defended by a massive, timber-framed rampart

with an external ditch, is one of the best examples.

It originally was proposed that there were two rows

of houses, about seventy in all, but research leaves

room to doubt this figure and even the contempo-

raneity of the structures. Differing in internal layout

is the contemporary Altes Schloss, near Potsdam in

160

ANCIENT EUROPE

eastern Germany. There, within a roughly pear-

shaped enclosure about 100 meters in greatest

width, some thirty houses occurred in at least five

rows, along with storage pits and a well. Such sites

indicate the emergence of agglomerated settle-

ments of considerable size.

Apart from the large-scale excavations of the

proto-urban sites of the Late La Tène period, such

as Manching in Bavaria and Mont Beuvray in

France, emphasis in hillfort excavations over the last

half of the twentieth century has concentrated to a

large extent on the nature of defensive construction.

There was great variety in the details, of course, but,

in broad terms, during the Bronze and into the Iron

Age there were two essential styles: those with verti-

cal faces and those that originally presented a slop-

ing surface to the exterior. Without excavation,

however, it generally is impossible to distinguish be-

tween the two.

Among the many forms of timber-laced de-

fenses are those of the so-called Kastenbau type, in-

volving boxlike compartments of longitudinal and

transverse beams filled with stones and rubble. They

were built without the vertical timbers at front or

back that are features of the widespread box ram-

part. These ramparts, of necessity, possessed trans-

verse beams through the body of the rampart to

prevent the outward pressure and collapse of the

uprights. A variant of this is the Altkönig-Preist type

(named after two typical examples in Germany),

which is characterized by the additional presence of

stone walls at the front and the particularly heavy

use of internal timbers. Other, less elaborate forms

of construction are known, including those where

the uprights were secured in position by the trans-

verse lane alone and those with verticals on the front

only, the supporting transverses being held in place

solely by the weight of the bank. The culmination

of timber-laced construction was the massive murus

Gallicus of the Late La Tène period, which pos-

sessed ramparts of nailed box construction with an

outer masonry facing and, on occasion, a substantial

internal earthen support. Such ramparts enclosed

settlements that often were of considerable size,

with houses arranged along streets and possessing

most of the specialist activities of the true town, in-

cluding the minting of coins. In Gaul, in the last

century before Christ, the Roman general Julius

Caesar had no hesitation in using the term oppidum

to describe them.

Defenses of dump construction consisted of

wide, sloping ramparts of piled earth lacking the

support of timber elements. More economical to

build than were the timber-laced ramparts, a poten-

tial weakness was that the outer face, without sup-

port, of necessity sloped to the interior. Its height

thus was critical, and associated ditches of substan-

tial depth were common, especially in England. In

northern France a variant, the so-called Fécamp

type, possessed shallower but considerably broader

ditches. Some British hillforts were constructed

with the sloping outer face of the rampart continued

by the inner face of the ditch, thus maximizing the

defensive potential. Massive ramparts constructed

solely of rubble, such as the huge German site of

Otzenhausen, also occur. Its prodigious dimensions

alone were deemed sufficient for effective defense,

but, as elsewhere, the scale of the protective ram-

parts may well have been intended for more than

merely defensive use.

Entrances, potentially the weakest point in the

defensive circuit, included angled approaches, over-

lapping ramparts, mazelike arrangements of strate-

gically placed ramparts, and various timber con-

structions, including footbridges or towers.

Associated especially with the Late La Tène oppida,

inturned entrances were constructed to create long,

narrow passages along which attackers had to pro-

gress. Massive timber gateways, sometimes doubled

or even trebled, also were present.

The varying types of rampart construction can-

not in any way be seen as regular developments over

time. It seems more likely that from a number of

self-evident structural variables, individual building

teams chose specific construction methods that

were deemed suitable in the context of the available

workforce and for the immediate needs. The Late

La Tène oppida stand apart, however, as does the

spectacular mud-brick wall of the Late Hallstatt

Heuneburg hillfort in southwest Germany. The lat-

ter, an obvious imitation of a Mediterranean town

wall, emphasizes once again that functional consid-

erations alone were not always paramount concerns

in defensive construction.

The trend toward hillfort building that gath-

ered momentum across Europe from the later

HILLFORTS

ANCIENT EUROPE

161

Bronze Age onward can be mirrored in Britain and

in Ireland. In the former area, Rams Hills, Berk-

shire, and the Breidden, Powys, represent early ex-

amples. In Ireland, too, modern investigations

show with increasing clarity that the centuries c.

1000

B.C. witnessed a significant explosion in hill-

fort construction. Rathgall, County Wicklow;

Mooghaun, County Clare; and Haughey’s Fort,

County Armagh, all now yielding radiocarbon dates

between 1000 and 900

B.C., are but three examples

of this early development. In all cases occupation of

some permanence has been recognized.

Britain, with more than three thousand struc-

tures of notionally hillfort character, presents acute

problems of definition. The classic examples, num-

bering several hundred, occur in south-central En-

gland in a broad band that runs from the southern

coast to northern Wales. Construction, as noted,

commenced early in the millennium, but the major

sites belong to the period from the mid-millennium

onward. Timber-laced ramparts of types compara-

ble to those found on the European mainland have

been identified (with the notable absence of the

murus Gallicus) and, of course, massive defenses of

earth alone, often in multiple form, are widespread.

Entrances of varied complexity occur, including

those of inturned form. The latter resemble the in-

turned entrances in Europe, but it must be stressed

that the British forts are not a product of invading

groups, as was once believed. They are entirely in-

digenous developments.

Large-scale excavation at selected sites, includ-

ing Danebury, Hampshire; Maiden Castle, Dorset;

Croft Ambrey, Hertfordshire; and elsewhere, has

provided extensive information on the nature of

hillforts in late prehistoric Britain. Danebury, a tri-

ple-ramparted hillfort of 5 hectares, was subjected

to research excavation over twenty seasons, which

ultimately exposed 57 percent of the interior. This

site has provided us with the most detailed and

comprehensive insights into the nature of the late

prehistoric hillfort in Britain.

Three main phases of activity, reflected in the

three ramparts, were recognized, and dating evi-

dence indicates that the site was in use from about

550

B.C. to the beginning of the Christian era. The

innermost, primary rampart is a massive earthen

construction with a deep, V-sectioned ditch: from

ditch base to the crest of the bank was a distance of

16.1 meters, dimensions surpassed only by the cor-

responding inner defense at Maiden Castle, which

totaled an astonishing 25.2 meters. Initially, there

were two entrances and later just one, and they were

developed to a level of exceptional defensive com-

plexity, providing complex, mazelike approaches to

the interior. Large, strategically placed caches of

sling stones underlined the military aspect of the

construction.

Within the enclosure, houses, both rectangular

and circular, were aligned along streets extending

more or less east to west across the interior. Well

over one hundred houses were identified, but not

all of them were contemporary. Numerous small

square or rectangular structures, which may have

been grain silos, also were revealed. Most spectacu-

lar were the 2,400-odd pits densely concentrated in

all excavated zones, superficially resembling the sur-

face of Gruyère cheese. These pits, carefully dug

and as deep as 3 meters, generally are seen as

having functioned for the storage of grain. In the

center were four small rectangular structures, which

might have been temples. Extensive evidence for

a wide range of secular activities also was brought

to light.

The most remarkable feature of Danebury was

the evidence for grain storage on what must have

been a prodigious scale. The enormous storage ca-

pacity implied seems far in excess of the needs of the

occupants of Danebury, a number estimated to have

been between 200 and 350 at any one time. It has

been suggested that the primary function of Dane-

bury was to act as a central place for the storage and

protection of grain for the peoples of the surround-

ing landscape.

Danebury is the classic British hillfort, but it is

scarcely typical for the whole island. In Scotland, for

example, structures of other types occur, including

those with various forms of timber lacing. Most no-

table, however, are the curious vitrified forts, so

called because of the intense burning to which the

stones of the ramparts have been subjected. These

sites have engendered considerable discussion—

accidental burning, hostile action, or even deliber-

ate burning by the inhabitants of the forts have been

suggested to explain the vitrification. Hostile action

perhaps is most likely, but in any event such ram-

parts originally must have been laced with timber.

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

162

ANCIENT EUROPE

The great southern English hillforts mirror the

trend toward centralization, if not urbanization,

that had already begun on the European mainland

in the latter part of the second century

B.C. Belgic

influences in southern England advanced this trend

a step further, but, as was the case on the mainlaind,

it was halted by Roman occupation, soon to be re-

born in another guise under the Pax Romana, or age

of Roman peace (37

B.C.–A.D. 180).

See also Maiden Castle vol. 1, part 1); Hambledon Hill

(vol. 1, part 3); Hallstatt (vol. 2, part 6); Oppida

(vol. 2, part 6); Manching (vol. 2, part 6); Danebury

(vol. 2, part 6); The Heuneburg (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avery, Michael. Hillfort Defences of Southern Britain. Ox-

ford: Tempus Reparatum, 1993.

Collis, John. R Oppida: Earliest Towns North of the Alps.

Sheffield, U.K.: University of Sheffield, 1984.

Harding, D. W., ed. Hillforts: Later Prehistoric Earthworks

in Britain and Ireland. London and New York: Aca-

demic, 1976.

B

ARRY RAFTERY

HILLFORTS

ANCIENT EUROPE

163

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

ORIGINS OF IRON PRODUCTION

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Ironworking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

■

Iron is potentially superior to bronze and is much

more common than copper and tin, bronze’s con-

stituents. Iron’s workable ores are widespread in

Europe and particularly abundant in the Alpine re-

gion. The advantage of iron’s abundance was offset

because ancient technology could not take full ad-

vantage of its properties. Furnace temperatures

could not reach iron’s relatively high melting point.

During the Bronze Age, small bits of iron occasion-

ally must have been produced during copper smelt-

ing, but metalworkers could not melt it as they

could other metals. When iron ore was intentionally

smelted in ancient times, the iron was reduced to

metal in the solid state, leaving a spongy mass with

slag still trapped in pores. Unlike bronze, which

could be cast, iron had to be worked in the solid

state to turn it into useful shapes. A smith reheated

it in a forge to soften the metal to liquefy any

trapped slag and then repeatedly hammered it to

force out as much slag as possible while shaping the

iron into ingots or finished forms. Reheating and

hammering were used in working bronze—they im-

prove the metal. Because iron could not be melted,

it could not be enhanced by mixing with other met-

als, and pure iron does not respond favorably to

hammering and reheating, as bronze does. Tech-

niques for dealing consistently with molten iron

were not developed in Europe until postmedieval

times.

Iron in the solid state takes up carbon and forms

a product called steel, but this process requires spe-

cial smelting conditions that did not occur often in

ancient furnaces. There is another chance to intro-

duce carbon into iron during forging, but this so-

called case hardening is extremely difficult to

achieve. Once steel can be produced on a consistent

basis, it does have many advantages over bronze. It

is almost as hard as bronze and can be further

quench-hardened—reheated and dunked into

water. The subsequent extremely hard but brittle

steel can be reheated again, and a balance can be

achieved between hardness and toughness that is

vastly superior to bronze. Steel production is, how-

ever, a labor-intensive process requiring specialized

skill.

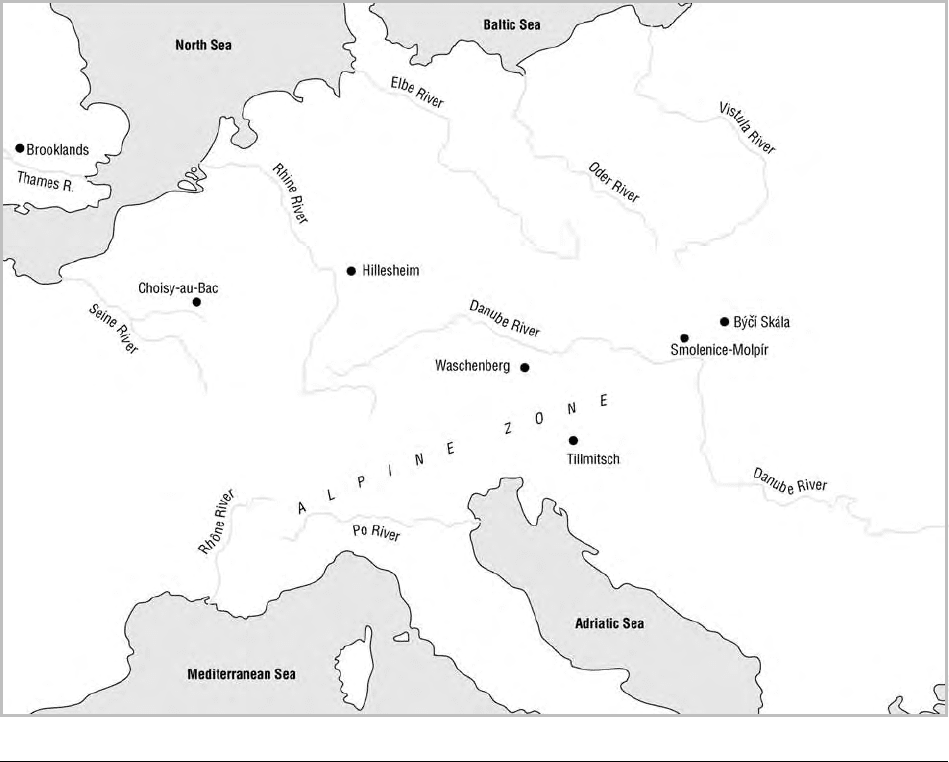

Archaeological evidence for iron production

takes four forms: production sites (furnaces and

forges), by-products (slag and unused ore), tools,

and finished objects. Slag has been excavated at nu-

merous Early Iron Age sites, often in fill, but pro-

duction areas have been identified definitively at

fewer than ten sites. Fortunately, these sites span al-

most the full time and space of Early Iron Age Eu-

rope: the earliest is Tillmitsch in the southeastern

164

ANCIENT EUROPE

Iron production sites from 800 to 400 B.C.

Alps in Austria, dated to 800 B.C., and the latest is

Brooklands in southern England, well outside of the

Alpine region and dated to 400

B.C. The map shows

these two sites and the five more best-known sites

that fall between them chronologically, all within

the Alpine zone. In general, these sites were hill-

forts involved in long-distance trade with the Medi-

terranean world. They bear evidence of other craft

production, suggesting that they were regional

centers with at least part-time artisans trading fin-

ished goods to a hinterland. The raw materials

they received in return enabled them to support

themselves and also to tap into the long-distance

trade.

Smelting and smithing took place at the same

locations, and smelting was carried out in simple

furnaces where the charge was allowed to cool in

place. Forges were of uncomplicated open design

not conducive to case hardening. Several dozen

slags have been analyzed from some of these sites

and from other less well-defined provenances dated

to the Early Iron Age. These slags uniformly suggest

smelting temperatures of 1,100–1,200°C (2,000–

2,200°F), consistent with the type of simple furnace

excavated.

Tools—hammers, tongs, and anvils themselves

made of iron—are quite rare from Early Iron Age

Europe and generally have been found in graves.

They, too, reflect a simple technology. On the other

hand, by definition, thousands upon thousands of

iron objects are known from the Early Iron Age, and

by now hundreds of these artifacts have been ana-

lyzed. Most of these objects come from graves, a

few from settlements, and a handful from the pro-

duction sites. The earliest iron objects in barbarian

Europe are parts of jewelry, sometimes covered with

ORIGINS OF IRON PRODUCTION

ANCIENT EUROPE

165

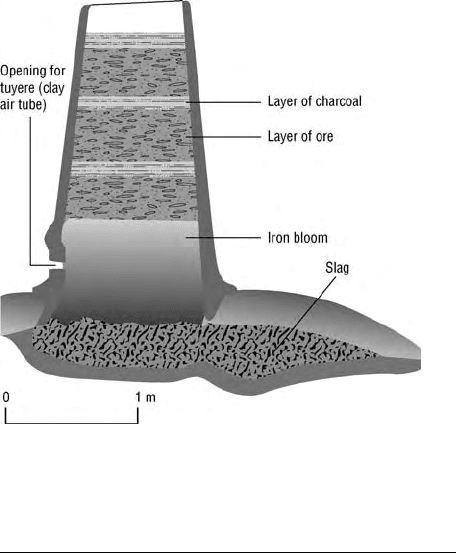

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of a typical shaft furnace of

the Iron Age. In this case the slag has been tapped off.

In some shaft furnaces and in simple bowl furnaces, the

slag is allowed to solidify in place, above the iron bloom.

ADAPTED FROM HTTP://MEMBERS.AON.AT/DBUNDSCH/LATENE.HTM.

bronze. Weapons are found a bit later, primarily in

graves. Agricultural tools date only to the Late Iron

Age.

Analysis has shown that the earliest objects,

even the weapons, were almost all made of plain

iron. They were not intentionally improved during

the forging process, although a few were of steel

produced accidentally in the smelting process. The

few objects exhibiting case hardening or quench

hardening were apparently southern imports.

Throughout the Early Iron Age, techniques for im-

proving iron developed slowly, and the most sophis-

ticated techniques do not appear until the end of

the Iron Age.

During the transition from the Bronze Age to

the Iron Age, the barbarians of temperate Europe

were in indirect but steady contact with Mediterra-

nean peoples. Iron production was pioneered in the

Alpine region c. 800

B.C., at regional centers that

already had advanced methods for working in

bronze and were in contact with the south. The

Greeks had sophisticated steel metallurgy, and ob-

jects of trade entered the barbarian world. The

northern bronzesmiths would have recognized iron

as an occasional by-product of copper smelting that

they had not found particularly useful. The presence

of a small amount of Mediterranean iron of superior

quality might have spurred barbarian investigations

into the new metal, or local conditions brought on

by trade and other factors might have led them to

experiment with a variety of pyrotechnologies. In

any event, there is no evidence that they learned

iron production from the south, and sophisticated

techniques were developed slowly over a long peri-

od of time out of local bronzesmithing traditions.

The earliest iron was inferior to bronze and not suit-

able for many applications, so there was no major

technological advantage to adopting it. Iron was at

first a decorative material and then came to be used

to replace bronze in a few very specific applications,

notably in certain types of funerary goods.

Nevertheless, the practice of ironworking

spread north and west by a combination of trade

and technology transfer. Although in most cases the

development continued to be indigenous, in some

cases actual migration may have been involved.

Ironworking rapidly reached Poland, Germany, and

France; it reached northern and western Europe

somewhat later. Each local area seems to have devel-

oped ironworking according to its own trajectory.

Although the use of iron must have had feedback on

other aspects of society, it was the other social forces

that led to iron production rather than vice versa.

The barbarians developed indigenous technology

that was to underpin their society from the Late

Iron Age until almost modern times.

See also Early Metallurgy in Southeastern Europe (vol.

1, part 4); Ironworking (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ehrenreich, Robert M. Trade, Technology, and the Ironwork-

ing Community in the Iron Age of Southern Britain.

BAR British Series, no. 144. Oxford: British Archaeo-

logical Reports, 1985.

Geselowitz, Michael N. “The Role of Iron Production in the

Formation of an ‘Iron Age Economy’ in Central Eu-

rope.” Research in Economic Anthropology 10 (1988):

225–255.

Pleiner, Radomír. “Early Iron Metallurgy in Europe.” In The

Coming of the Age of Iron. Edited by Theodore A. Wer-

time and James D. Muhly, pp. 375–415. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1980.

Raymond, Robert. Out of the Fiery Furnace: The Impact of

Metals on the History of Mankind. Philadelphia: Univer-

sity of Pennsylvania Press, 2000. (Recent general histo-

ry of metallurgy written for the general public.)

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

166

ANCIENT EUROPE

Rostoker, William, and Bennet Bronson. Pre-Industrial

Iron: Its Technology and Ethnology. Archaeomaterials

Monograph, no. 1. Philadelphia: University of Pennsyl-

vania, 1990. (Survey of prehistoric iron production;

much material covers Europe but is somewhat techni-

cal.)

Scott, Brian G. Early Irish Ironworking. Belfast: Ulster Mu-

seum, 1990.

Tylecote, Ronald F. A History of Metallurgy. 2d ed. London:

Institute of Materials, 1992. (General, if somewhat

technical, history of metallurgy, including iron and fo-

cusing on Europe.)

Wertime, Theodore A., and James D. Muhly. The Coming

of the Age of Iron. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University

Press, 1980. (Collection of regional syntheses about the

origins of iron production worldwide plus background

essays on method and theory.)

M

ICHAEL N. GESELOWITZ

■

IRONWORKING

By about 300 B.C., iron production was common

throughout Europe. The abundance of iron ore,

however, was offset by the limitations of the bloom-

ery process through which iron was produced. Fur-

nace temperatures could not reach iron’s relatively

high melting point. When iron ore was smelted, the

iron was reduced to metal in the solid state, leaving

a spongy mass (called the sponge or bloom) with

slag still trapped in pores. A smith reheated the

bloom in a forge to soften the metal and liquefy any

trapped slag and then hammered it repeatedly to

force out as much slag as possible while shaping the

iron into ingots or finished forms. The wrought iron

so produced was relatively pure and therefore not

very hard. The smiths learned that they could har-

den the iron by placing it in the forge in contact

with organic materials. It is now known that this

technique, called case hardening, works by intro-

ducing carbon into the surface of the iron, convert-

ing it to steel. The process was labor-intensive and

difficult to control. Furthermore, a great deal of

fuel—charcoal, produced from wood—was needed

for both smelting and forging. Although wood was

readily available in barbarian Europe, procuring the

wood represented another labor-intensive step in

production.

Ironworking in this early era was carried out in

many settlements of various sizes. The level of pro-

duction was small-scale, the political economy had

to support a full-time specialist, and the quality of

the product could not always be assured. As a result,

iron was used primarily for weapons, funerary

goods, and other items with a strong political and

social component and only to a very limited extent

for agricultural tools.

The nature of iron production began to change

with the rise of urbanism in Late Iron Age Europe.

After about 200

B.C., large, complex settlements

began to emerge in specific areas of Europe. These

oppida were based in part on long-distance trade

with the Roman world as well as control of local po-

litical, social, and economic networks. Evidence of

large-scale iron production occurs on most of these

sites, and some even appear to have specialized in

iron production. Several well-excavated oppida in

Bavaria, such as Manching and Kelheim, have pro-

vided evidence of every facet of ironworking, from

mining through forging, and the analysis of the

finds from these sites confirms the view of site spe-

cialization and of trade with Rome. The Roman

need for iron may have led at least in part to this

urban phenomenon. In any event, the formation of

large centers with higher population densities and

greater social differentiation and specialization cer-

tainly allowed and encouraged the support of large-

scale iron production, which in turn made iron

more important to the economy. Not only do a

wider variety of tools and weapons of iron appear,

but evidence also includes the appearance of iron

bars that seem to have been used as a kind of curren-

cy. The use of the iron plowshare almost certainly

had a major impact on the rest of the economy.

Ironworking also continued to be carried out on the

smaller settlements, although their economic rela-

tionship to the centers is not clear.

In addition to the changes in the quantity of

iron, there were qualitative changes as well. First,

the simple shaft furnaces were replaced by slightly

more-advanced domed furnaces, which did not

create much greater temperatures but were more

consistent and had larger capacity. Archaeometal-

lurgical analyses from many parts of Europe have

shown that the smiths learned that steel could be re-

heated and quenched to produce an even harder

substance and that the resulting quench-hardened

steel could be reheated to achieve a balance between

hardness and toughness. This technique was not

IRONWORKING

ANCIENT EUROPE

167

known in the Early Iron Age and would not have

been obvious to early metalworkers because it does

not work on other metals such as bronze. The

smiths also learned how to weld a steel edge onto

a soft iron back without accidentally decarburiz-

ing—removing the carbon from—the steel, a diffi-

cult process that leads to a superior tool or weapon.

Various finds of smiths’ tools also attest to the range

of techniques available to them. They did not, how-

ever, learn to “pile” steel by alternating thin layers

of iron and steel, as was done in the Classical world.

There is some debate as to what extent the

smiths of the barbarian world developed these tech-

niques independently owing to their long experi-

ence with iron and to what extent the technology

diffused from the classical world. On the one hand,

at the time of the Celtic invasions of Italy in the

third century

B.C., classical sources make reference

to the inferior nature of the barbarians’ swords. On

the other hand, by the second century

B.C., the

sources speak of the outstanding quality of the steel

from Celtic Iberia. After the Roman conquest of

central and western Europe, Noricum—now the

province of Carinthia in the Austrian Alps—became

the major steel supplier for the empire.

The situation of barbarian iron production out-

side the Roman limes after the Roman conquest

until the fall of the empire was a mixed one. Some

areas, such as the Holy Cross Mountains in Poland,

continued to specialize in and produce large quanti-

ties of iron for local consumption and trade with

Rome. Other areas underwent a decentralization

and technical regression. Still others, such as Ireland

and Scandinavia, which had originally been outside

the zone of increased and improved iron produc-

tion, gradually developed their own industries,

probably under the influence of their trading and

raiding relationships with Roman territories. It is

safe to say that, after the fall of the Roman Empire,

the barbarian world was everywhere an iron-based

economy but one that depended on relatively basic

techniques and somewhat decentralized produc-

tion.

See also Oppida (vol. 2, part 6); Origins of Iron

Production (vol. 2, part 6).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ehrenreich, Robert M. Trade, Technology, and the Ironwork-

ing Community in the Iron Age of Southern Britain.

BAR British Series, no. 144. Oxford: British Archaeo-

logical Reports, 1985.

Pleiner, Radomír. “Early Iron Metallurgy in Europe.” In The

Coming of the Age of Iron. Edited by Theodore A. Wer-

time and James D. Muhly, pp. 375–415. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1980.

Raymond, Robert. Out of the Fiery Furnace: The Impact of

Metals on the History of Mankind. University Park, Pa.:

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986.

Rostoker, William, and Bennet Bronson. Pre-Industrial

Iron: Its Technology and Ethnology. Archaeomaterials

Monograph, no. 1. Philadelphia: University of Pennsyl-

vania, 1990.

Scott, Brian G. Early Irish Ironworking. Belfast: Ulster Mu-

seum, 1990

Tylecote, Ronald F. A History of Metallurgy. 2d ed. London:

Institute of Materials, 1992.

Wells, Peter S. Settlement, Economy, and Cultural Change at

the End of the European Iron Age: Excavations at Kel-

heim in Bavaria, 1987–1991. Archaeology Series, no. 6.

Ann Arbor, Mich.: International Monographs in Pre-

history, 1993. (Includes general discussion of the oppi-

da and ironworking, including data from other sites,

such as Manching, plus specialist reports on the iron-

working finds from Kelheim.)

Wertime, Theodore A., and James D. Muhly. The Coming

of the Age of Iron. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University

Press, 1980.

M

ICHAEL N. GESELOWITZ

6: THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

168

ANCIENT EUROPE

THE EUROPEAN IRON AGE, C. 800 B.C.– A.D. 400

COINAGE OF IRON AGE EUROPE

■

Coinage was an invention of the Greek inhabitants

of Asia Minor in the seventh century

B.C. Over the

next three centuries, the concept spread through

the rest of the Mediterranean world, including the

Greek colonies of southern France and northeastern

Spain, such as Emporion (Ampurias) and Massalia

(Marseille), although it was not until c. 300

B.C.

that the Romans adopted a regular coinage. At

about this time the idea also began to penetrate

northward into barbarian Europe. By the second

century

B.C. some form of coinage was in use over

much of the Continent, from the Black Sea and the

Danube basin to the Atlantic coast of France and

Spain and as far north as Bohemia and central Ger-

many. The inhabitants of southeastern Britain were

among the last to adopt coinage and continued to

produce it in the first century

A.D., after the other

coin-using regions had been absorbed into the

Roman Empire. Most of the barbarian groups who

adopted coinage were Celtic speaking but also in-

cluded Germans, Iberians, Illyrians, Ligurians, and

Thracians.

At the outset Iron Age coinage was either of

gold or of silver and derived from Greek models.

Precious metal issues in the name of the powerful

Macedonian rulers of the late fourth century

B.C.,

Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, were by

far the most influential prototypes, but the coins of

various Greek colonies also were imitated. Over

time distinctive local and regional coinage traditions

began to emerge as indigenous moneyers added fea-

tures and designs of their own. None of the earliest

Iron Age coinages is meaningfully inscribed, but

from the second century

B.C. onward many issuers

began to put their names—and sometimes such de-

tails as a title or mint name—on their coins. Most

legends are in Greek or Latin letters or a mixture of

the two, although Iberian, Illyrian, and Italiote

scripts were all used in certain areas. As Rome be-

came the dominant Mediterranean power, its coin-

age also began to be imitated by Iron Age groups.

Bronze coinage was a relatively late innovation and

essentially was confined to western Europe. Tri-

metallic coinages are found only in a few parts of

southeastern Britain and northern France, whose

rulers were effectively already under Roman domi-

nation.

Two main and essentially discrete zones of Iron

Age coinage can be discerned based on different

Greek models. Over a vast area of southern Europe,

extending from the Balkans and the Danube basin

through the Po Basin in Italy and to the Rhône and

Garonne basins of southern France, almost all Iron

Age coinages were in silver. Farther to the north,

however, in Bohemia, southern Germany, northern

France, and eventually Britain they were initially of

gold. A third, smaller zone existed in Spain and

Mediterranean France west of the Rhône, where

from the late third to the early first centuries

B.C.

numerous groups struck bronze (and occasionally

silver) coinages, mostly modeled on the contempo-

rary bronze issues of Roman Spain. None of the

peoples inhabiting the north European plain or

Scandinavia adopted coinage at this stage, possibly

because it did not fit with their dominant ideology

or value system.

ANCIENT EUROPE

169