Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PARTV

Stratigraphy and

Basin Analysis

Well-stratified Paleozoic

sedimentary rocks

exposed in the North Rim

of the Grand Canyon,

Arizona.

397

398

E

mphasis in preceding parts of this book has been on sedimentary processes,

the environments in which these processes take place, and the properties of

sedimentary

rocks generated in these environments. In this final

part, we

focus on a different aspect of sedimentary rocks. Our concern here is not so much

sedimentary processes and detailed rock properties but rather the larger scale ver

tical and lateral relationships between units of sedimentary rock that are defined

on the basis of lithologic or physical properties, paleontological characteristics,

geophysical properties, age relationships, and geographic position and distribu

tion. It is the study of these characteristics of layered rocks that encompasses the

discipline of stratigraphy. Understanding the principles and terminology of

stratigraphy is essential to geologic study of sedimentary rocks because stratigra

phy provides the framework within which sediments can be studied systematical

ly. It allows the geologist to bring together the details of sediment composition,

texture, structure, and other features into an environmental and temporal synthe

sis from which we can interpret the broader aspects of Earth history.

Prior to the 1960s, the discipline of stratigraphy was conceed particularly

with stratigraphic nomenclature; the more classical concepts of lithostratigraphic,

biostratigraphic, and chronostratigraphic successions in given areas; and correlation

of

these successions between areas. Lithostratigraphy deals with the lithology or

physical properties of strata and their organization into units on e basis of litho

logic character. Biostratiaphy is the study of rock units on the basis of the fossils

they contain. Chronostratigraphy ( chrono = time) deals with the ages of strata

and their time relations. These established principles are still the backbone of

stratigraphy; however, today's students must go beyond these basic principles.

They must also acquire a thorough understanding of depositional systems and be

able to apply stratigraphic and sedimentological principles to interptation of stra

ta within the context of global plate tectonics. is means, among other thgs, be

coming familiar with comparatively new branches of stratigraphy that have

developed since the early 1960s as new concepts and methods of studying sedimen

tary rocks and other rocks by remote-sensing techniques have unfolded. For exam

ple, the concept of depositional sequences, which are packages of strata bounded by

unconformities, has gained particular promence since the late 1970s. This concept

has now become so important that we refer to study of sequences as sequence

stratigraphy. Two new oshoots of stratigraphy that have made particularly impor

tant contributions to our understanding of the physical stratigraphic relationships,

ages, and environmental significance of subsurface strata and oceanic sediments are

seismic stratigraphy, which is the study of stratigraphic and depositional facies as

terpreted from seismic data, and magnetostratigraphy, which deals with

strati

graphic relationships on the basis of magnetic properties of sedimentary rocks and

layered volcanic rocks. We also recognize sub-branches of stratigraphy such as event

stratigraphy (correlation of sedimentary units on the basis of marker beds or event

horizons), cyclostratigraphy (study of short-period, high-frequency, sedimentary

cycles the stratigraphic record, particularly by use of oxygen-isotope data), and

chemostratigraphy (correlation on the basis of stable isotopes such as oxygen, car

bon, and strontium). Application of these new concepts and techniques makes pos

sible subdivision of stratigraphic successions to relatively small units, e.g.,

< 1000-3000 years for Quaternary strata and 225,000-2,000,000 years for Triassic

strata (Kidd and Hailwood, 1993). Such fe-scale stratigraphic resolution is now

commonly referred to as high-resolution stratigraphy.

We explore all of these stratigraphic concepts in the next few chapters. In the

final chapter of the book, we take a look at basin analysis. Basin analysis is a kind

of umbrella under which we integrate and apply all of the sedimentologic and

stratigraphic principles presented in this book. Together with fundamental tecton

ic concepts, basin analysis allows us to develop an understanding of the rocks that

fill sedimentary basins in order to interpret their geologic history and evaluate

their economic significance .

Lithostratigraphy

12.1 INTRODUCTION

P

erhaps the most fundamental kind of stratigraphic study is recognition, sub

division, and correlation (establishing equivalency) of sedimentary rocks on

the basis of their lithology, that is, lithostratigraphy. The term litholo is

used by geologists in two different but related ways. Strictly speaking, it refers to

study and description of the physical character of rocks, particularly in hand spec

imens and outcrops (Bates and Jackson, 198 0). It is used also to refer to these phys

ical characteristics: rock type, color, mineral composition, and grain size are all

lithologic characteristics. For example, we may refer to the lithology of a particu

lar stratigraphic unit as sandstone, shale, limestone, and so forth. Thus, lithostrati

graphic units are rock units defined or delineated on the basis of their physical

properties, and lithostratigraphy deals with the study of the stratigraphic relation

ships among strata that can be identified on the basis of lithology.

In this chapter, we begin study of stratigraphic principles by briefly dis

cussg the nature of lithostratigraphic units, followed by exploration of the vari

ous types of contacts that separate these units. We then consider the important

concepts of sedimentary facies and depositional sequences. The essentials of

st ratigraphic nomenclature and classification as they apply to lithostratigraphic

its are discussed next, including examination of the North American Code of

Stratigraphic Nomenclature. Finally, correlation of lithostratigraphic units is ex

pl ained and the various methods of correlation described.

12.2 TYPES OF LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC UNITS

Lithostratigraphic units are bodies of sedimentary, extrusive igneous, metasedi

mentary, or metavolcanic rock distinguished on the basis of lithologic characteris

tics. A lithostratigraphic unit generally conforms to the law of superposition,

which states that in any succession of strata, not disturbed or overtued since de

pition, younger rocks lie above older rocks. Lithostratigraphic units are also com

mly stratified and tabular in form. They are recognized and defined on the basis

of observable rock characteristics. Boundaries between different units may be

placed at clearly identifiable or distinguished contacts or may be drawn arbitrarily

399

400

Chapter 12 I Lithostratigraphy

within a zone of gradation. Definition of lithostratigraphic units is based on a

stratotype (a designated type unit), or type section, consisting of readily accessible

rocks, where possible, in natural outcrops, excavations, mines, or bore holes.

Lithostratigraphic units are defined strictly on the basis of lithic criteria as deter

mined by descriptions of actual rock materials. They carry no connotation of age.

They cannot be defined on the basis of paleontologic criteria, and they are de

pendent of time concepts. They may be established in subsurface sections as well

as in rock units exposed at the surface, but they must be established on the basis of

lithic characteristics and not on geophysical properties or other criteria. Geophys

ical criteria, described in Chapter 13, may be used to aid in fixing boundaries of

subsurface lithostratigraphic units, but the units cannot defined exclusively on

the basis of remotely sensed physical properties.

Wheeler and Mallory (1956) introduced the term lithosome to refer to masses

of rock of essentially uniform character and having intertonguing relationships wi

adjacent masses of different liology. Thus, we speak of shale lithosomes, limestone

lithosomes, sand-shale lithosomes, and so forth. Krumbein and Sloss (1963) clarify

the meaning of lithosome by asking readers to imane the body of rock that would

emerge if it was possible to preserve a single rock type, such as sandstone, and d

solve

away all other rock types. The resulting sandstone body would thus appear as

a roughly tabular mass with intricately shaped boundaries. ese irregular bound

aries would represent its surfaces of contact with erosion surfaces and with other

rock masses of diering constitution above, below, and to the sides. Lithosomes

have no specified size limits and may range in gross shape from thin, sheetlike or

blanketlike units to thick prisms, or narrow, elongated shoestrings.

Of course, stratigraphic units of a single lithology rarely exist as isolated bod

ies. They are commonly in contact with oer rock bodies of different lithology.

important part of lithostratigraphy is identifyg and understanding the nature of

contacts between vertically supeosed or laterally adjacent bodies. Another impor

tant aspect is the identification of single lithosomes, groups of lithosomes, or subdi

visions of lithosomes that are so distinctive that they form lithostratigraphic units

that can be distinguished from other units that may lie above, below, or adjacent.

The fundamental lithostratigraphic unit of this type is the formation. A

formation is a lithologically distinctive stratigraphic unit that is large enough in

scale to be mappable at the surface or traceable in the subsurface. It may encom

pass a single lithosome, or part of an intertonguing lithosome, and thus consist of

a single lithology. Alternatively, a formation can be composed of two or mo

lithosomes and thus may include rocks of different lithology. Some formations

may

divided into smaller stratigraphic units called members, which, in tum,

may

be divided into smaller distinctive units called beds. Beds are the smallest

formal lithostratigraphic units. Formations having some kind of stratigraphic

unity can be combined to form groups, and groups can be combined to form

supergroups. All formal lithostratigraphic units are given names that are derived

from some geographic feature in the area where they are studied.

Subdivision of thick units of strata into smaller lithostratigraphic units such

as formations is essential for tracing and correlating strata bo in outcrop and in

the subsurface. We will come back to discussion of these formal stratigraphic units

near the end of this chapter. First, however, we examine the nature of contacts be

tween stratigraphic units and the lateral and vertical facies relationships that char

acterize strata.

12.3 STRATIGRAPHIC RELATIONS

Different lithologic units are separated from each other by contacts, which are pla

nar or irregular surfaces between different types of rocks. Vertically superposed

12.3 Stratigraphic Relations

401

strata are said to be either conformable or unconformable depending upon conti-

nuity of deposition. Conformable strata are characterized by unbroken deposi-

tional assemblages, generally deposited in parallel order, in which layers are

formed one above the other by more or less uninterrupted deposition. The surface

that separates conformable strata is a confoity, that is, a surface that separates

younger strata from older rocks but along which there is no physical evidence of

nondeposition. A conformable contact indicates that no siificant break or hiatus

in deposition has occurred. A hiatus a break or interruption in the continuity of

the geologic record. It represents periods of geolog time (short or long) for which

there are no sediments or strata.

Contacts between strata that do not succeed underlying rocks in immediate

order

of age, or that do not fit together with them as part of a continuous whole,

are called unconformities. Thus, an unconformity is a surface of erosion or

nondeposition, separating younger strata from older rocks, that represents a

significant hiatus. Unconformities indicate a lack of continuity in deposition and

rrespond to periods of nondeposition, weathering, or erosion, either subaerial

or subaqueous, prior to deposition of younger beds. Unconformities thus repre

sent a substantial break in the geologic record that may correspond to periods of

erosion or nondeposition lasting millions or even hundreds of millions of years.

Contacts are also present between laterally adjacent lithostratigraphic units.

These contacts are formed between rock units of equivalent age that developed

different lithologies owing to different conditions in the depositional environ

ment. Excluded from discussion here are contacts between laterally adjacent bod

ies that arise from postdepositional faulting. Contacts between laterally adjacent

bodies may be gradational, where one rock type changes gradually into another,

or they may be intertonguing, that is, pinching or wedging out within another for

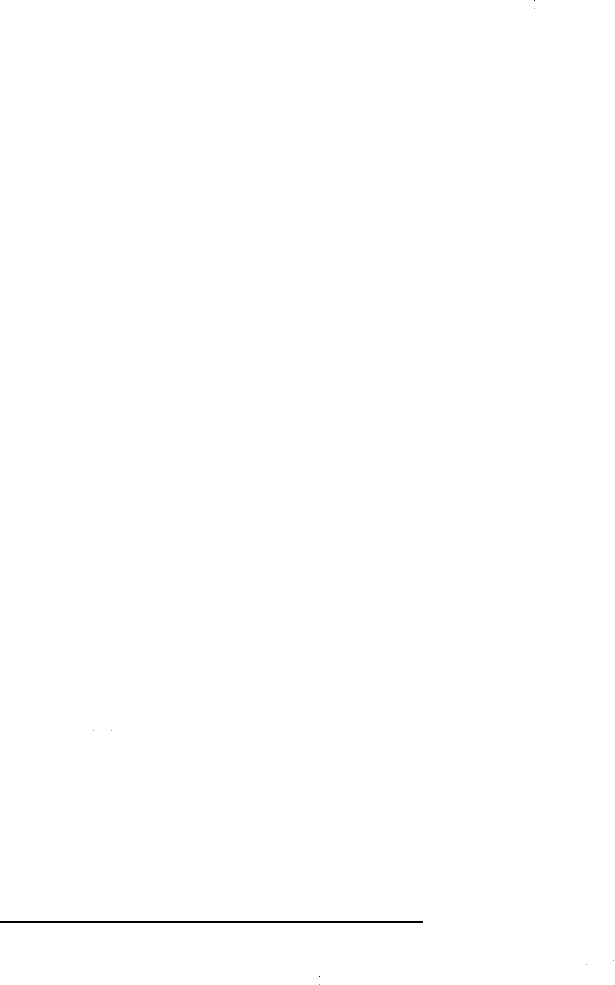

mation (see Figures 12.1-12.4).

Conta between Conformable Strata

Contacts between conformable strata may be either abrupt or gradational. Abrupt

contacts directly separate beds of distinctly different lithology (Figs. 12.1, 12.2).

Most abrupt contacts coincide with primary depositional bedding planes that

formed as a result of changes local depositional conditions, as discussed in

Chapter 4; thus, the contacts are commonly very sharp. In general, bedding planes

represent minor interruptions in depositional conditions, Such minor deposition

al

breaks, involving only short hiatuses in sedimentation with little or no erosion

before deposition is resumed, are called diastems. Abrupt contacts may be caused

also by postdepositional chemical alteration of beds, producing changes in color

owing to oxidation or reduction of iron-bearing minerals, changes in grain size

owing to recrystallization or dolomitization, or changes in resistance to weather

g owing to cementation by silica or carbonate minerals.

Conformable contacts are said to be gradational if the change from one

lithology to another is less marked than abrupt contacts, reflecting gradual change

in depositional conditions with time (Fig. 12.1 ). Gradational contacts may be of ei

ther the progressive gradual type or the intercalated type. Progressive gradual

contacts occur where one lithology grades into another by progressive, more

less uniform changes in ain size, mineral composition, or other physical charac

teristics. Examples include sandstone units that become progressively finer

grained upward until they change to mudstones, or quartz-rich sandstones that

become progressively enriched upward in lithic fragments until they change to

lithic arenites. Intercalated contacts are gradational contacts that occur because of

an increasing number of thin interbeds of another lithology that appear upward in

the section (Figs. 12.1, 12.3).

402

Chapter 12 I Lithostratigraphy

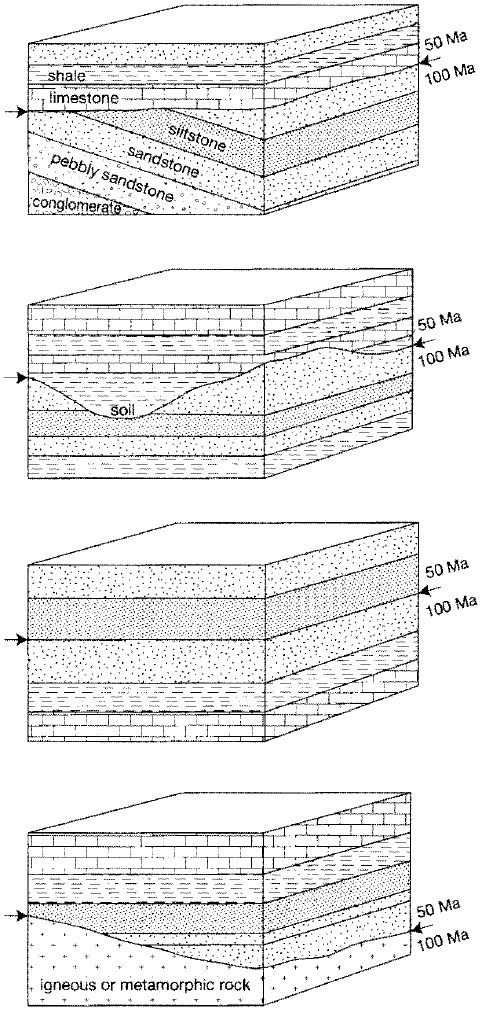

Figure 12.1

Schematic representation of

the principal kinds of vertical

and lateral contacts between

lithologic units. Vertical con

tacts include abrupt, pro

gressive gradual, and

intercalated. Lithologic units

may be laterally continuous

or they may change laterally

by pinchout, intertonguing,

or lateral gradation. See

Figures 12.2-1 2.4 for exam

ples of actual contacts.

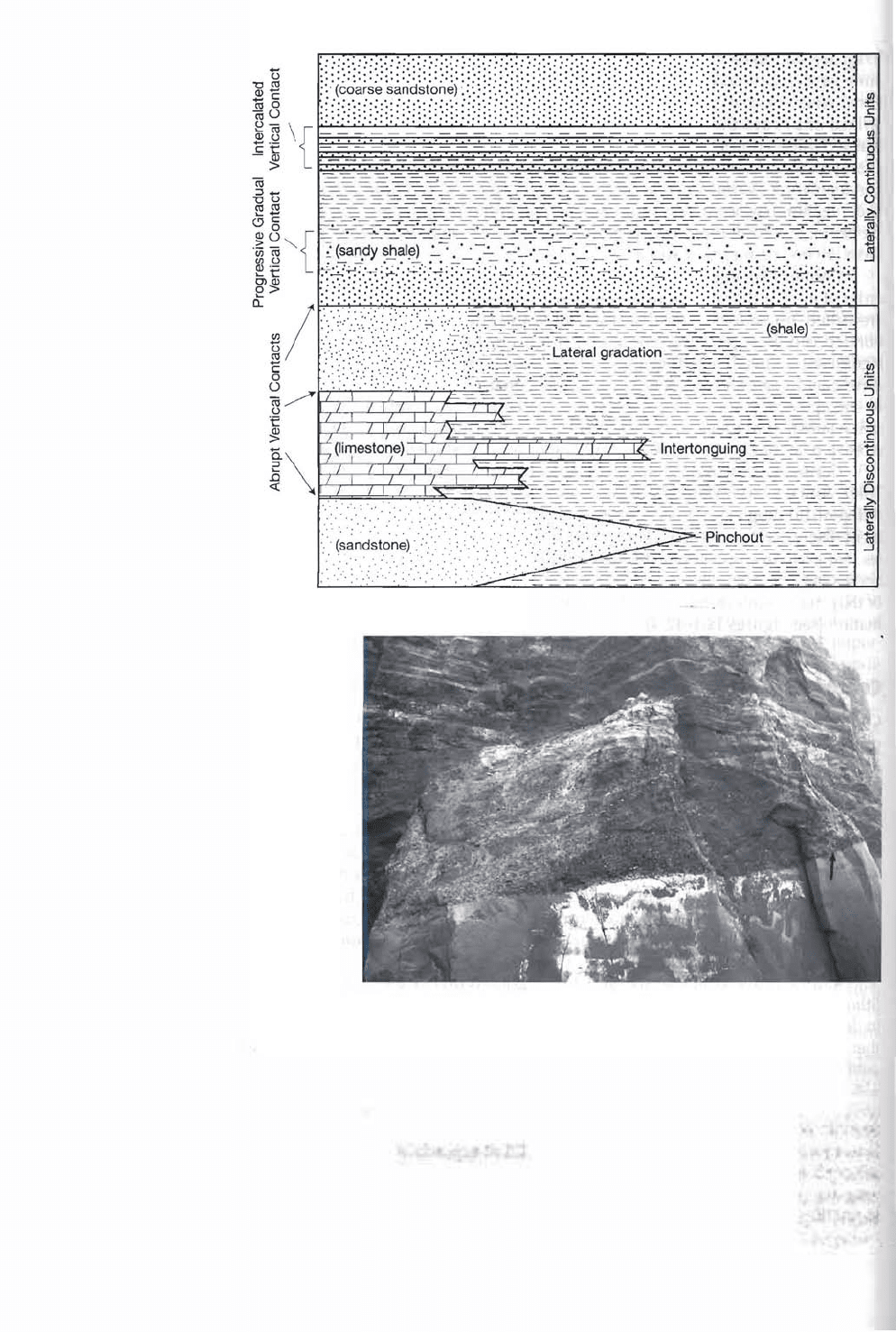

Figure 12.2

Abrupt contact (arrow) between massive

bedded sandstone below and fine-grained

conglomerate above. Miocene deposits near

Blacklock Point, Southwest Oregon Coast.

Contacts between Laterally Adjacent lithosomes

In addition to vertical boundaries deeated by contacts, stratigraphic ts also

have fite lateral boundaries. They do not extend indefinitely laterally but must

eventually terminate, either abruptly as a result of erosion or more gradually by

change to a different lithology. Some sedimentary w1its are laterally discontuous

in the sense

that lateral changes lithology may occur within single outcrops or at

least within a local area. Many nonmarine deposits, such as alluvial-fan deposits,

exhibit such lateral discontuity. Lateral changes may be accompanied by pogres

sive tg of units to extction-pinch-outs (Figs. 12.1, 12.4); lateral splitting of

a lithologic unit into many thin Lmits that pinch-out independently-intertonguing;

12.3 Stratigraphic Relations

403

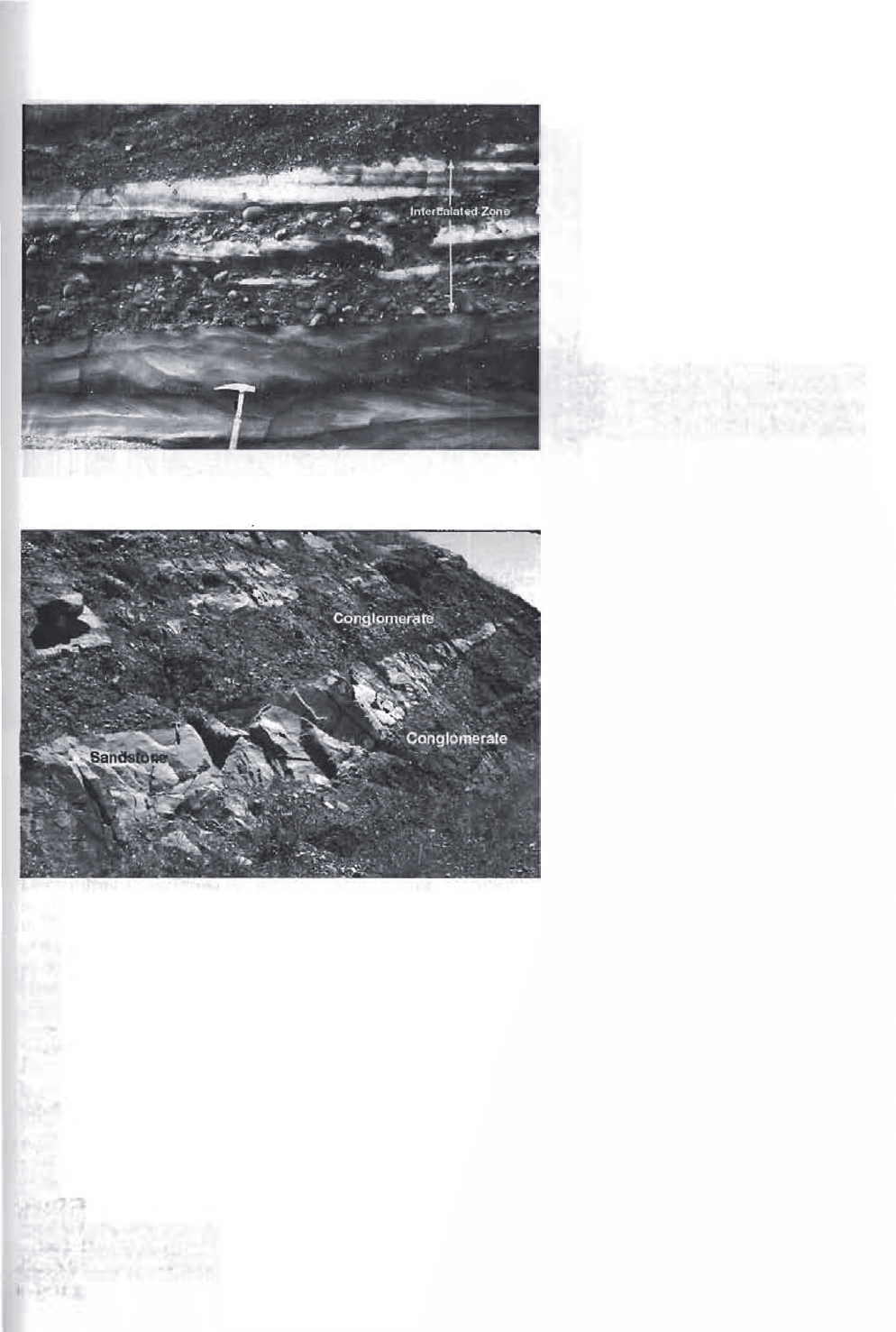

Figure 12.3

Gradation from sandstone below through a

zone of intercalated thin conglomerates and

sandstones (light) to conglomerate at the

top of the section. Miocene deposi near

Blacklock Point. Southwest Oregon Coast.

Figure 12.4

Pinch-out. Note how the sandstone bed

(light)

pinches out abruptly to the right and

disappears into the conglomerate. Creta

ceous (?) deposits, near Ashland, southern

Oregon.

or progressive lateral gradation, similar to progressive vertical gradation. We

speak of sedimentary units that do not terminate ithin single outcrops or local

areas as being laterally continuous (Fig. 12.1). If traced far enough, of course such

units must also eventually terminate. Many marine strata such as shelf sandstones,

limestones, and central-basin evaporites exhibit lateral continuity.

Unconformable Contacts

As mentioned, contacts between strata that do not succeed underlying rocks verti

cally

in immediate order of age are called unconformities. Four types of uncon

formable contacts (unconformities) are recoed: (1) angular unconformity, (2)

disconformity, (3) paraconformity, and (4) nonconformity (Fig. 12.5). Unconformi

ts are oized by an angular relationship between strata (angular unconfor

mities} the presence of a marked erosional surface separating these strata (e.g.,

dionformities), marked disparity in age of rocks above and below the unconfor

ty (e.g., paraconformities) , and the nature of the rocks underlying the surface of

404

Chapter 12 I Lithostratigraphy

Figure 12.5

Schematic representation of four basic kinds of unconfor

mities. Arrows indicate the unconformity surface. For the

purpose of illustration, the youngest strata below the un

conformity surface in each diagram is shown to have a

(hypothetical) age of 1 00 million years and the oldest

strata above the unconformity surface an age of 50 mil

lion years, indicating a hiatus in each case of 50 million

years. [Modified from Dunbar, C. 0., and ]. Rodgers,

1957, Principles of stratigraphy: john Wiley & Sons, New

Yo rk, Fig. 57, p. 117, reprinted by permission.]

A. Angular Unconformity

B. Disconformity

C. Paracontormity

D. Nonconformity

unconformity. The rst three types of unconformities occur between bodies

of

sedimentary rock. Nonconformities occur between sedimentary rock and meta

morphic or igneous rock.

An

lar Unconformi

An angular unconformity is a type of unconformity in which younger sediments

rest upon the eroded surface of tilted or folded older rocks; that is, the older rocks

dip at a dierent, commonly steeper, angle than

do the younger rocks (Fig. 12.5A).

The unconformity surface may be essentially planar or markedly irregular. gular

12.3 Stratigraphic Relations

405

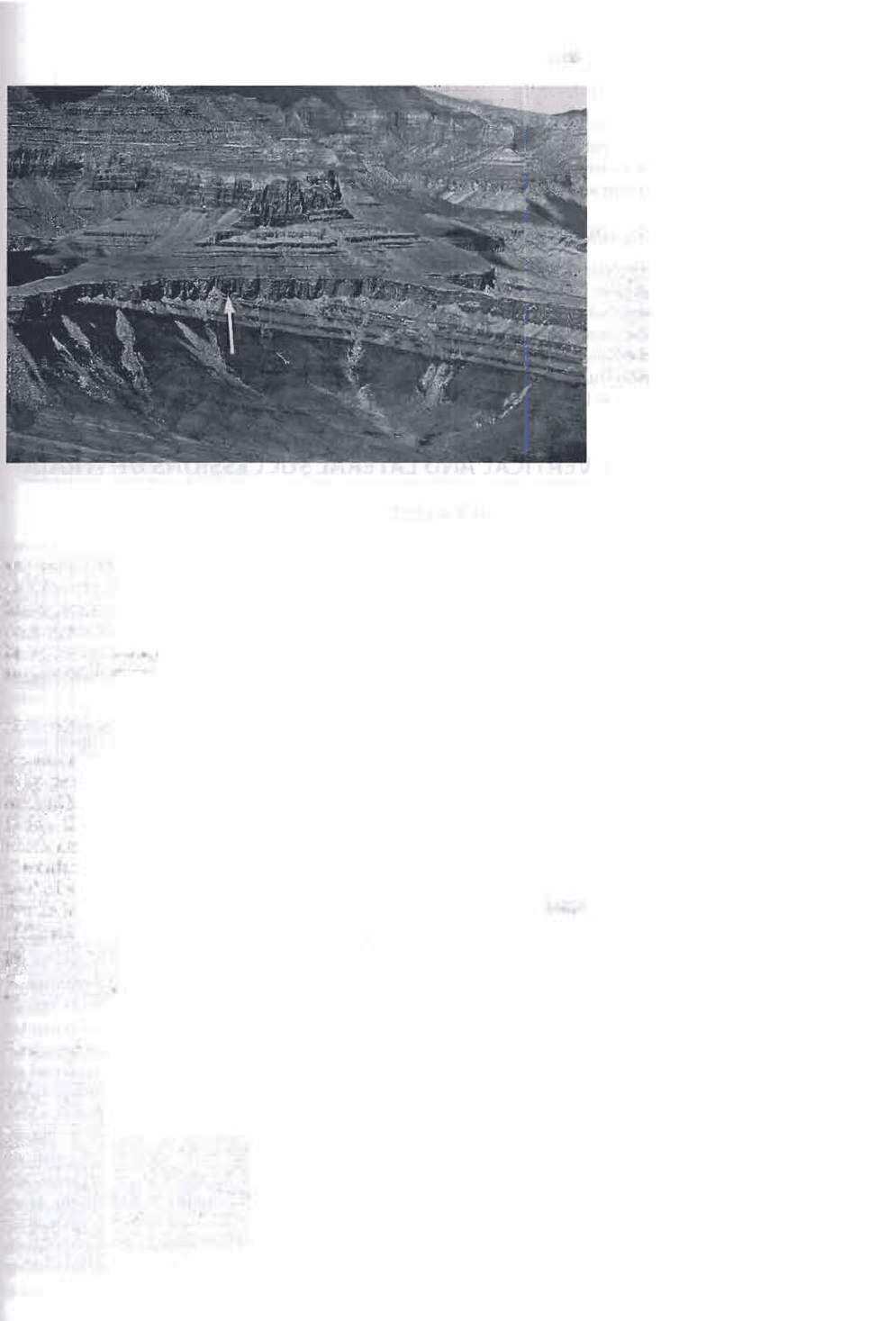

Figure 12.6

Major angular unconformity

(arrow) between tilted sedimentary

rocks of the Grand Canyon Group

(Precambrian) and overlying, nearly

horizontal, Tapeats Sandstone

(Cambrian). Younger Paleozoic stra

ta are exposed above the Tapeats.

View from Desert Overlook, South

east Rim, Grand Canyon, Arizona.

unconformities may be confined to limited geographic areas (local tmconformities)

or may extend for tens or even hundreds of kilometers (regional unconformities).

Some angular unconformities are visible in a single outcrop (Fig. 12.6). By con

trast, regional unconformities between stratigraphic units of very low dip may not

be apparent in a single outcrop and may require detailed mapping over a large

aa before they can be identified.

Disconformi

An unconformity surface above and below which the bedding planes are essen

tially parallel and in which the contact between younger and older beds is

marked by a visible, irregular or uneven erosional surface is a disconformity (Fig.

12.5B). Disconformities are most easily recognized by this erosional surface,

which may be channeled and which may have relief ranging to tens of meters.

Disconformity surfaces, as well as angular unconformity surfaces, may be

marked also by "fossil" soil zones (paleosols) or may include lag-gravel deposits

at lie immediately above the unconformable surface and that contain pebbles

of the same lithology as the lithology of the underlying unit. Disconformities are

psumed to form as a result of a significant period of erosion throughout which

older

rocks remained essentially horizontal during nearly vertical uplift and sub

sequent dowt

'

warping.

Pa raconfonni

A paraconformity is an obscure unconformity characterized by beds above and

below the unconformity contact that are parallel and in which no erosional

surface

or other physical evidence of unconformity is discernible. The uncon

formity contact may even appear to be a simple bedding plane (Fig. 12.5C).

Paraconformities are not easily recognized and must be identified on the basis of

a

gap in the rock record (because of nondeposition or erosion) as determined

from paleontologic evidence such as absence of fa unal zones or abrupt faunal

changes. In other words, rocks of a particular age are missing, as determined by

fossils or other evidence.

406

Chapter 12 I Lithostratigraphy

Nonconfoity

An unconformity developed between sedimentary rock and older igneous or mas

sive metamorphic rock that has been exposed to erosion prior to being covered by

sediments is a nonconformity (Fig. 12.50). Nonconformity surfaces probably rep

resent an extended period of erosion.

Significance of Unconfoities

The presence of unconformities has considerable significance in sedimentological

studies. Many stratigraphic successions are bounded by unconformities, dicat

g that these successions are incomplete records of past sedimentation. Not only

do unconformities show that some part of the stratigraphic record is missing, but

they also indicate that an important geologic event took place during the time pe

riod (hiatus) represented by the unconformity-an episode of uplift and erosion

or, likely, an extended period of nondeposition.

12.4 VERTICAL AND LATERAL SUCCESSIONS OF STRATA

Nature of Vertical Successions

As discussed, conformities and unconformities divide sedimentary rocks into ver

tical successions of beds, each characterized by a particular lithologic aspect. Dif

ferent types of beds can succeed each other vertically in a great variety of ways,

and distinctions can be drawn between rock units characterized by lithologic uni

formity, lithologic heterogeneity, and cyclic successions. Rock units that have

complete lithologic uniformity are rare, although many beds may display a high de

gree of uniformity in color, grain size, composition, or resistance to weathering.

Beds that are most likely to be uniform are fe-grained sediments deposited

slowly under essentially uniform conditions in deeper water, or coarser sediments

that have been deposited rapidly by some type of mass sediment transport mech

anism such as grain flow. By contrast, heterogeneous bodies of sedimentary strata

are characterized by internal variations or irregularities in properties. Heteroge

neous units may include strata such as extremely poorly sorted debris-flow de

posits, as well as thick units broken inteally by thinner beds characterized by

differences in grain size or bedding features.

Cyclic Successions

Many stratigraphic successions display repetitions of strata that reflect a succes

sion of related depositional processes and conditions that are repeated in the

same order. Such repetitious events are referred to as cyclic sedimentation or

rhythmic sedimentation. Cyclic sedimentation leads to the formation of vertic

successions of sedimentary strata that display repetitive orderly arrangement of

different kinds of sediments. The term cyclic sediment has been used for a wide

variety of repetitious strata including such small-scale features as presumed an

nually

deposited varves in glacial lakes as well as large-scale sediment cycles

caused by long-period, recurring migration of depositional environments. Other

common examples of repetitive deposits clude rhythmically bedded turbidites,

laminated evaporite deposits, limestone-shale rhythmic successions, coal cy

clothems (repeated cycles involving coal deposition), black shale deposits, and

chert deposits. Cyclic successions occur on all continents in essenally every

stratigraphic system. They are produced by processes that range in geograpc

scope and duration from very local, short-term events-such as seasonal climatic

changes that generate varves-to global changes in sea level that may involve en

tire geologic periods.