Boggs S. Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

5.3 onglomerates

1 35

ensands (glauconitic sands), phosphatic sandstones, and calcarenaceous

dstones (composed of sand-size carbonate grains). These rocks are not te sand-

stones (siliciclastic rocks) but rather are chemical/biochemical sedimentary rocks

(Chapters 6 and 7).

5.3 CONGLOMETES

The te onglomerates is used in this book as a general class name for sedimen

tary that contain a substantial fraction (at least 30 percent) of gravel-size

(>2 mm) particles (Fig. 5.8A). Breccias (Fig. 5.88), which are composed of very

angular, gravel-size fragments, are not distinguished from conglomerates in the

succeeding diussion. Conglomerates are common in stratigraphic successions of

all ages but probably make up less than l percent by weight of the total sedimen

tary ck mass (Garrels and McKenzie, 1971, p. 40). They are closely related to

ndstones in terms of origin and depositional mechanisms, and they contain

some of the·same kinds of sedimentary structures (e.g., tabular and trough cross

bding, g�'aded bedding).

Paicle Composition

Conglomerate may contain gravel-size pieces of individual minerals such as

quartz; however, most of the gravel-size framework grains are rock fragments

(clasts). Individual sand- or mud-size mineral grains are commonly present as a

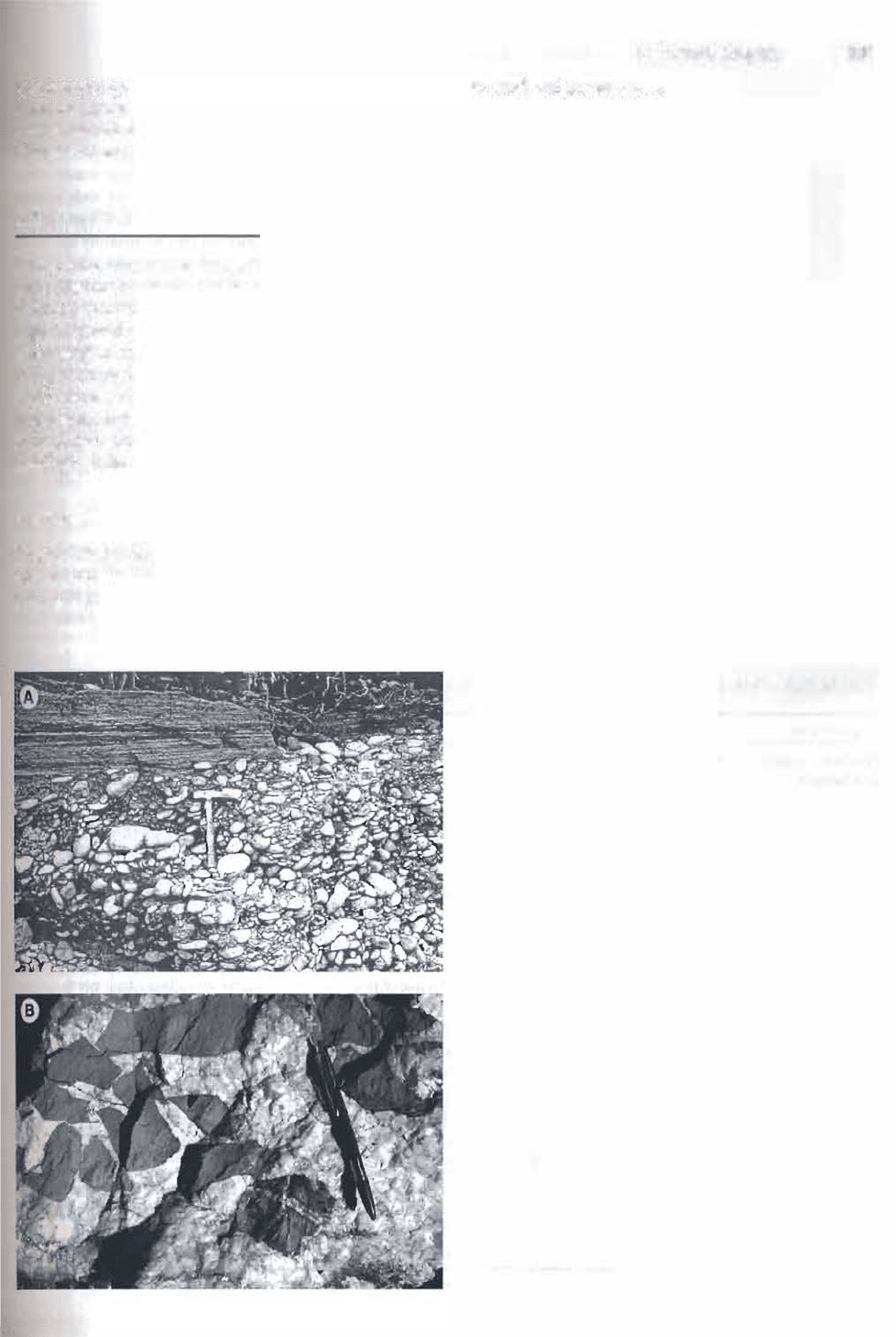

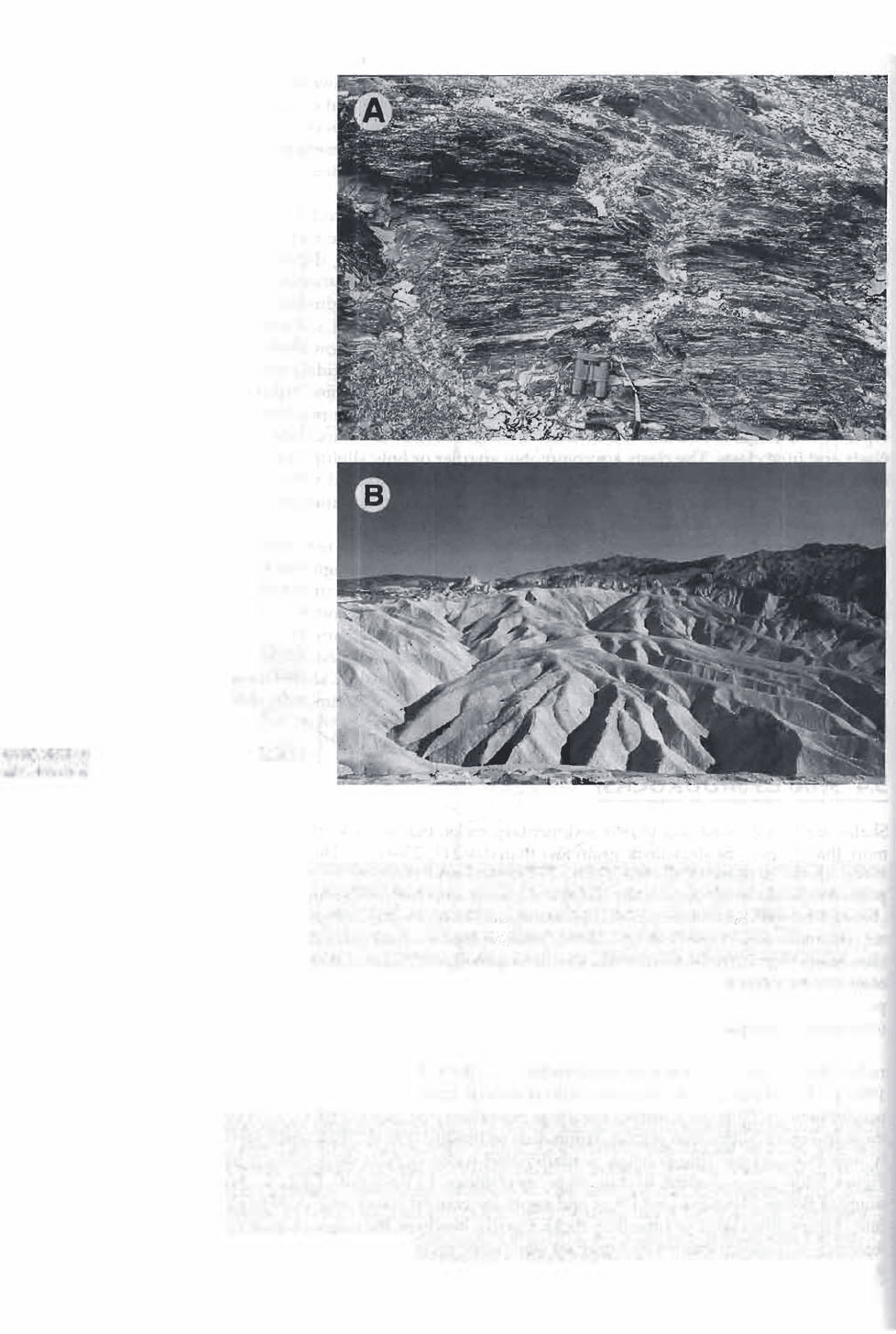

Figure 5.8

A. Clast-supported conglomerate underlying laminated

sands. Terrace deposits (Holocene) of the Umpqua River,

southwest Oregon. B. Large breccia clasts (dark) cement

ed with calcite. Nevada Limestone (Devonian), Treasure

Peak, Nevada. Photograph courtesy of Walter

Yo ungquist.

136 Chapter 5 I Siliciclastic Sedimentary Rocks

matrix. Any kind of igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary rock may be present in

a conglomerate, depending upon source rocks and depositional conditions. Some

conglomerates are composed of only the most stable and durable kinds of clasts

(quartzite, chert, vein-quartz). Stable conglomerates composed mainly of a single

clast type are referred to by Pettijohn (1975) as oligomict conglomerates. Most

oligomict conglomerates were probably derived from mixed parent-rock sources

that included less stable rock types. Continued recycling of mixed ultrastable and

unstable clasts through several generations of conglomerates ultimately led to se

lective destruction of the less stable clasts and concentration of stable clasts. Con

glomerates that contain an assortment of many kinds of clasts are polymict

conglomerates. Polymict conglomerates that are made up of a mixture of largely

unstable or metastable clasts such as basalt, limestone, shale, and metamorphic

phyllite are commonly called petromict conglomerates (Pettijohn, 1975). Almost

any combination of these clast types is possible in a petromict conglomerate. The

matrix of conglomerates commonly consists of various kinds of clay minerals and

fine micas and/ or silt- or sand-size quartz, feldspars, rock fragments, and heavy

minerals. The matrix may be cemented with quartz, calcite, hematite, clay, or other

cements.

Classification

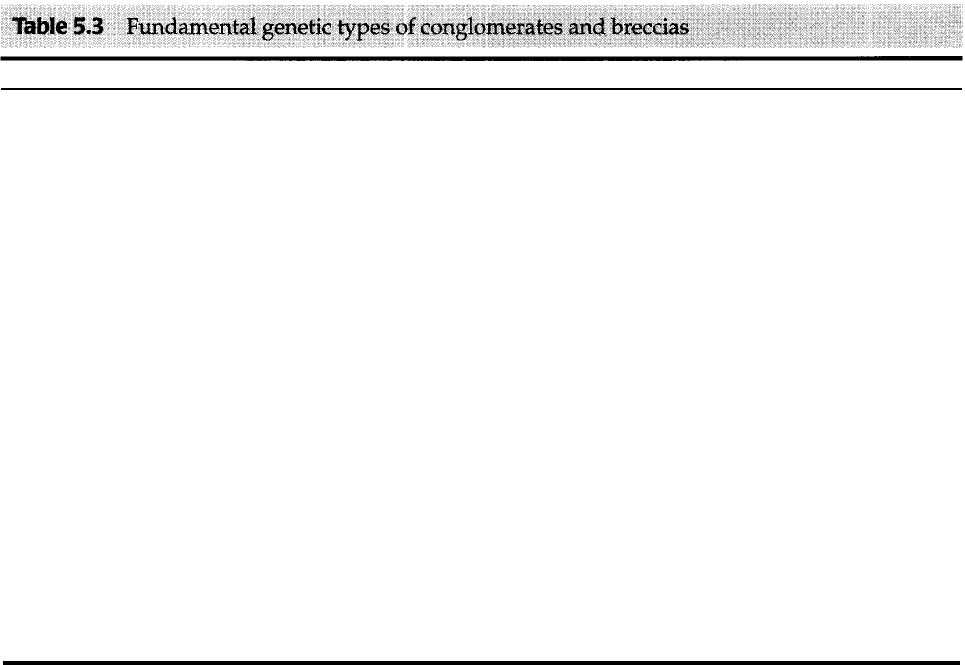

Conglomerates can originate by several processes, as shown in Table 5.3. We are

interested most in epiclastic conglomerates, which form by breakdown of older

rocks through the processes of weathering and erosion. Epiclastic conglomerates

that are so rich in gravel-size framework grains that the gravel-size grains touch

l

e

5.3

fd en

l

genefk pes of co

n

glo��

d

�

fdas

�

�

�

Major typ es

Epiclastic conglomerate

and breccia

Vo lcanic breccia

Cataclastic breccia

Solution breccia

Meteorite impact breccia

Subtypes

Extraformational

conglomerate

and breccia

Intraformational

conglomerate

and breccia

Pyroclastic breccia

Auto breccia

Hyaloclastic breccia

Landslide and slump

breccia

Tectonic breccia: fault,

fold, crush breccia

Collapse breccia

Origin of clasts

Breakdown of older rocks of any kind through the processes of

weathering and erosion; deposition by fluid flows (water, ice)

and sediment gravity flows

Penecontemporaneous fragmentation of weakly consolidated

sedimentary beds; deposition by fluid flows and sediment

gravity flows

Explosive volcanic eruptions, either magmatic or phreatic

(steam) eruptions; deposited by air-falls or pyroclastic flows

Breakup of viscous, partially congealed lava owing to continued

movement of the lava

Shattering of hot, coherent magma into glassy fragments owing

to contact with water, snow, or water-saturated sediment

(quench fragmentation)

Breakup of rock owing to tensile stresses and impact during

sliding and slumping of rock masses

Breakage of brittle rock as a result of crustal movements

Breakage of brittle rock owing to collapse into an opening

created by solution or other processes

Insoluble fragments that remain after solution of more soluble

material; e.g., chert clasts concentrated by solution of

limestone

Shattering of rock owing to meteorite impact

Source: Modified from Pettijohn, F. J., 1975, Sedimenta

rocks, 3rd ed., Harper & Row, New York, p. 165.

5.3 Conglomerates

137

and form a supporting framework are called clast-supported conglomerates.

Clast-poor conglomerates that const of sparse gravels supported in a mud/ sand

matrix are called matrix-supported conglomerates. Boggs (1992, p. 212) suggests

that clast-supported conglomerates be referred to simply as conglomerates and

at matrix-supported conglomerates be called diamictites. Although the term di-

ictite

is often used for poorly sorted glacial deposits, it is actually a nongenetic

rm that can be applied to nonsorted or poorly sorted siliclastic sedimentary

cks that contain larger parcles of any size in a muddy matrix.

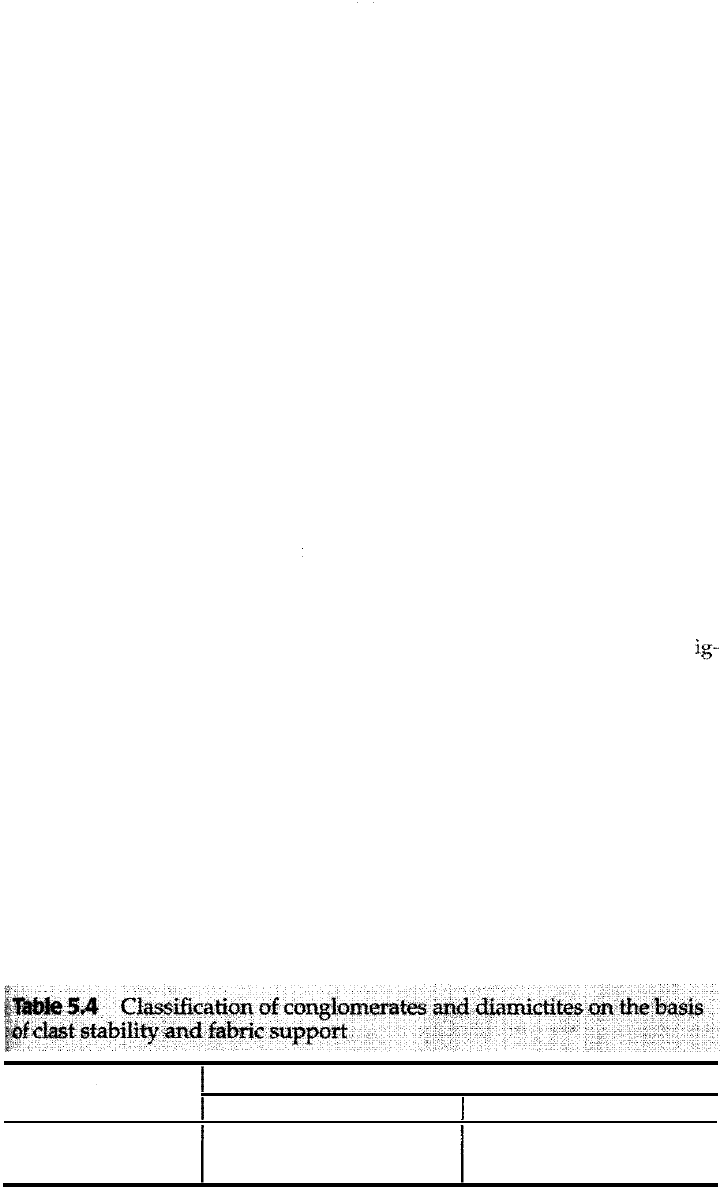

Conglomerates and diamictites can be further divided on the basis of clast sta

bility into quartzose (oligomict) conglomerate/diamictite and petromict conglom

ate/diactite on the basis of relative abundance of these clast types (Table 5.4).

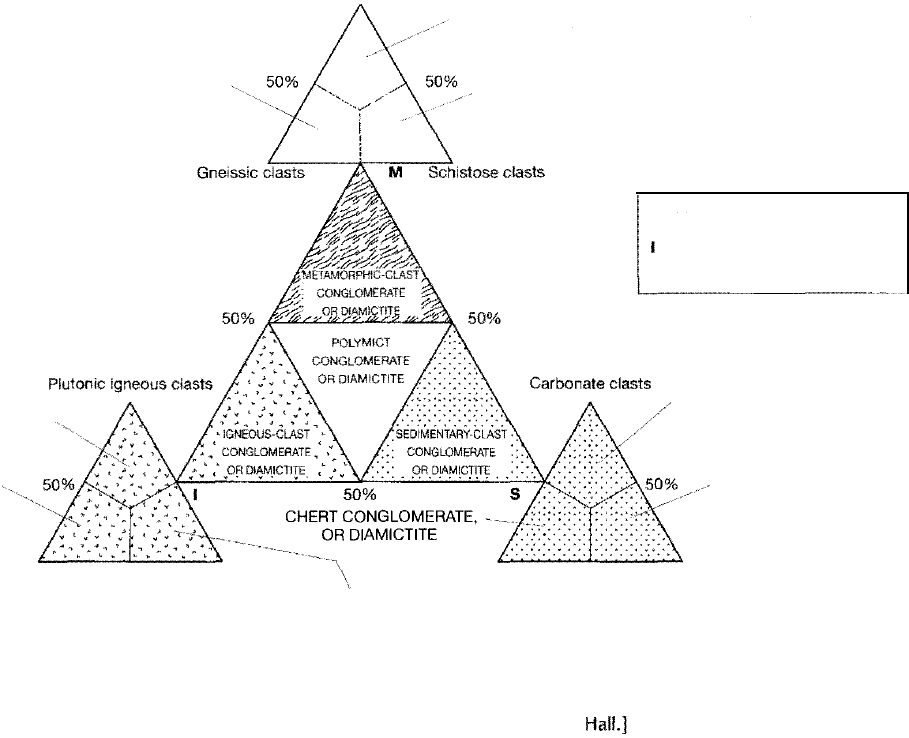

Furer classification on the basis of clast type (igneous, metamorphic, sedimenta

) can be made if desired (Fig. 5.9); however, such classification may not be nec

essary in many cases.

Origin and Occurrence of Conglomerates

Quarose (oligomict) conglomerates are derived from metasedimentary rocks

containing quartzite beds, igneous rocks containing quartz-filled veins, and sedi

mentary successions, particularly limestones, containing chert beds. As men

oned,

less stable rock types must have been destroyed by weathering, erosion,

and sediment transport, perhaps through several cycles of transport, to produce a

siduum of stable clasts. Because quartzose clasts represent only a small fraction

of a much larger original

body of rock, the total volume of quartzose conglomer

ates is small. They tend to occur as thin, pebbly layers or lenses of pebbles in dom

inantly sandstone units. They may be either clast-supported or matrix-supported.

Although their overall volume is small, quartzose conglomerates are common in

the geologic record ranging from the Precambrian to the Tertiary. Most quartzose

conglomerates appear to be of fluvial origin (Chapter 8) and are probably deposit

ma ly in braided streams. Marine, wave-worked quartzose conglomerates

that were deposited in the littoral (beach) environment are also known.

Most petromict conomerates are polymict conglomerates that consist of a

vaety of metastable clasts. They can be derived from many kinds of plutonic

neous, volcanic, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks, although the clasts in a

particular conglomerate may be dominantly one or another of these rock types.

Thus, a particular conglomerate may be a limestone conglomerate, a basalt con

glomerate, a schist conglomerate, and on. Conglomerates composed dominantly

of plutonic igneous clasts appear to be uncommon, probably because plutonic

rs such as granites tend to disintegrate into sand-size fragments rather than

larger blocks. The volume of ancient petromict conglomerates is far greater

than that of quartzose conglomerates. They form the truly great conglomerate

bodies of the geologic record and may reach thicknesses of thousands of meters.

Preservation of such great thicess of conglomerate implies rapid erosion of

sharp

ly elevated highlands or areas of active volcanism. Petromict conglomerates

may be transported by fluid-flow and sediment gravity-flow mecnisms; they

Percentage of

ultrastable clasts

>90

<90

Ty pe of fabric support

Clast-supported

Quartzose conglomerate

Petromict conglomerate

Matrix-supported

Quartzose diamictite

Petromict diamictite

.

w

Granoblastic and hornfelsic clasts

QUARTZ ITE, MARBLE, HORNFELS, ETC .

CONGLOMERATE

OR DIAMICTITE

GNEISS CONGLOMERATE

OR DIAMICTITE

SCHIST, PHYLLITE, SLATE, ETC.

CONGLOMERAT E OR DIAMICTITE

GRANITE, DIORITE,

GABBRO CONGLOMERATE,

OR DIAMICTITE

RHYOLITE, DACITE,

CONGLOMERATE,

OR DIAMICTITE

Felsic volcanic 50

%

Intermediate and mafic

\

Che clasts

Fire 5.9

clasts

volcanic clasts

ANDESITE, BASALT,

CONGLOMERAT E,

OR DIAMICTITE

50

%

M = META MORPHIC CLASTS

= IGNEOUS CLASTS

S = SEDIMENTARY CLASTS

LIMESTONE, DOLOMITE

CONGLOMERATE, OR

DIAMICTITE

SANDSTONE, SHALE ETC.

CONGLOMERATE, OR

DIAMICTITE

Siliciclastic clasts

Classification of conglomerate on the basis of clast lithology and fabric support. [From Boggs, 1992, Petrology of sedimenta rocks,

Fig. 6.3, p. 220: Macmillan Publishing Co., New York, reproduced by permission of Prentice

5.4 Shales (Mudrocks)

139

are deposited in environments ranging from uvial rough shallow marine to

deep marine. Deep-marine conglomerates are so-called resedimented con

g

lomer-

ates that were retransported from nearshore areas by tbidity currents or other

sediment gravity-ow processes. The bulk of the truly thick conglomerate bodies

(>20 m) were probably deposited in nonmarine (alluvial fan/braided river) set-

gs or deep-sea fan settings.

Intraformational conglomerates are composed of clasts of sediments be

lieved to have formed within depositional basins, in contrast to the clasts of ex

trarmational conglomerates that are derived from outside e depositional

basin. Intraformational conglomerates originate by penecontemporaneous defor

mation of semiconsolidated sediment and redeposition of the fragments fairly

dose to the site of deformation. Penecontemporaneous breakup of sediment to

form clasts may take place subaerially, such as by drying out of mud on a tidal flat,

or

under water. Subaqueous rip-ups of semiconsolidated muds by tidal currents,

waves, or sediment-gravity ows are possible causes. In any case, sedimen

on is interrupted only a short time ding this process. The most common

types of fragments found in traformational conglomerates are siliciclasc mud

as and lime clasts. The clasts are commonly angular or only slightly rounded,

suggesting little transport. In some beds, attened clasts are stacked virtually on

edge, apparently owing to unusually strong wave or current agitation, to form

what called ed

g

ewise con

g

lomerates (Pettijohn, 1975, p. 184).

Intraformational conglomerates commonly form thin beds, a few centime

rs to a meter in thickness, that may be laterally extensive. Although much less

abundant than extraformational conglomerates, they nonetheless occur in rocks of

many ages. So-called flat-pebble conglomerates composed of carbonate or limy

siltone clasts are particulay common in Cambrian-age rocks in various parts of

North America. They also occur in many oer early Paleozoic limestones of the

Appalachian region. Intraformational conglomerates composed of shale rip-up

asts embedded in the basal part of sandstone units are very common in sedi

mentary successions deposited by sediment gravity-flow pcesses.

5.4 SHALES (MUDROCKS)

Shales are fine-grained, siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, that is, rocks that contain

more an 50 percent siliciclastic grain less than 0.062 (1 /256) mm. Thus, they are

made up domantly of silt-size (1/16-1 /256 mm) and clay-size (<1 /256 mm)

pacles. Shale is an historically accepted class name for this group of rocks

(Toulot, 1960), equivalent to the class name sandstone, a usage accepted by Pot

ter, Maynard, d Pryor (1980, p. 12-15). These authors use the term shale as the

class name for all fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, but they divide

ales into several kinds, such as mudstones and mudshales, depending upon the

percentage of day-size constituents and the presence or absence of lamination

(discussed subsequently under classification).

the other hand, some auors prefer to use the class name mudrock,

rather than shale, for all fine-graed rocks (e.g., Blatt, Middleton, and Murray,

1980, p. 382). They divide mudrocks into shales (if laminated) or mudstones (if

nonlaminated). Thus, they restrict the usage of shale to fine-grained rocks, such as

ose in Figure 5.10A, that display lamination or fissility (the ability to split easi

ly into thin layers). Fine-grained, nonlaminated rocks such as those shown in

Figure 5.108 are, according to this usage, mudstones. In this book, l follow the

usage of Potter, Maynard, and Pryor and apply the general class name shale to all

e -grained siliclastic sedimentary rocks. Clearly, however, the usage of shale or

mudrock as a class name for ne-grained siliciclastic rocks is a matter of personal

pce.

140

Chapter 5 I Siliciclastic Sedimentary Rocks

Figure 5.10

A. Laminated (red) shale (pre-Mississippi

an), Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alas

ka. Note binoculars for scale. B.

Lacustrine mudstones (nonlaminated),

Furnace Creek Formation

(Miocene/Pliocene), Death Va lley, Califor

nia. Photograph by james Stovall.

Shales are abundant in sedimentary successions, making up roughly 50 per

cent of all the sedimentary rocks in the geologic record. Historically, shales have

been an understudied group of rocks, mainly because their fe grain size makes

them difficult to study with ordinary petrographic microscope. This perspec

tive is changing, however, as instruments are developed such as the scanning elec

tron microscope and electron probe microanalyzer that allow study of fine-size

grains at high magnification (e.g., Fig. 5.11).

Composition

Mineralogy

Shales are composed primarily of clay minerals and fine-size quartz and feldspars

(Table 5.5). They also contain various amounts of other minerals, including car

bonate minerals (calcite, dolomite, siderite), sulfides (pyrite, marcasite), iron ox

ides (goethite), and heavy merals, as well as a small amount of organic carbon.

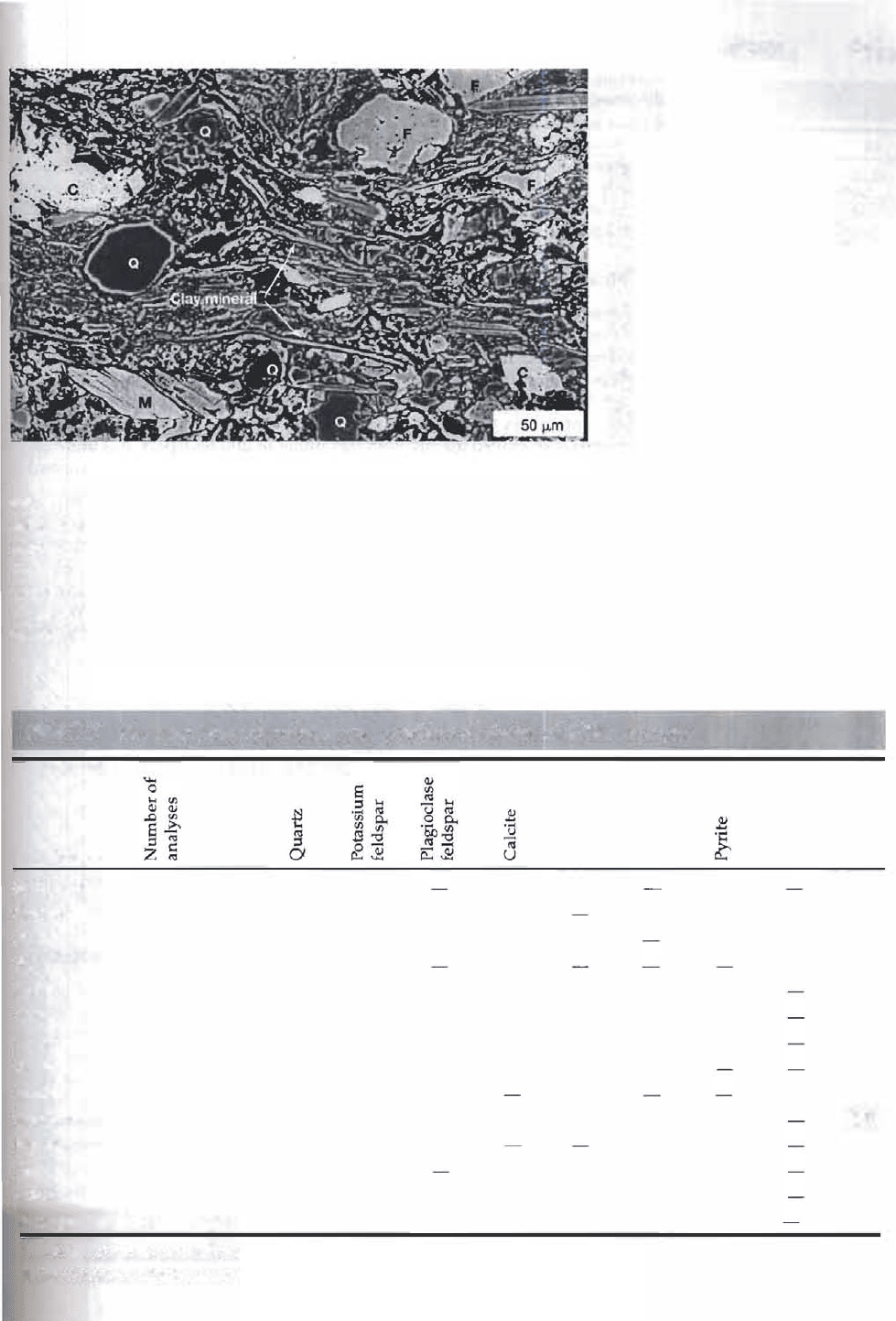

Figure 5.11 is a high-magnification photograph, taken by use of backscattered

scanning electron microscopy, which allows both the meralogy and texture of

this laminated shale to be examined. [See Krinsley et al., 1998, for discussion of the

use of backscattered electron microscopy the study of sedimentary rocks.] The

5.4 Shales (Mudrocks)

141

Figure 5.11

Backscattered scanning electron mi

croscope (BSE) photograph of a lami

nated shale. The elongated, pla, or

flaky minerals are clay minerals (illite)

and fine micas. Other coarser miner

als are quartz (Q), feldspar (F), calcite

(C), mica (M), and pyrite (very bright

mineral). Note that orientation of

clay minerals and fine micas creates

the lamination. Whitby Mudstone

(Jurassic), Yorkshire, England. Scale

bar = 50 pm. Photograph courtesy

of David Krinsley.

data in Table 5.5 show mineral composition as a ftmction of age. No discernible

nd of mineralogy vs. age is evident from this table, except possibly a slight

nd of decreasing feldspar with increasing age. Many factors affect the composi

tion of shales, including tectonic setting and provenance (source), depositional en

vironments, grain size, and burial diagenesis. Some minerals, such as carbonate

minerals and sulfides, form in the shales during burial as cements or replacement

minerals. Quartz, feldspars, and clay minerals are mainly detrital (terrigenous)

5.5

Av erage percent composion of ss of different ages

Age

Quaternary

Pliene

Miene

Oligene

Eene

Cretacus

Jurassic

Triaic

Permian

Penylvanian

ssissippi

vo

dovici

. ages

5

4

9

4

11

9

10

9

1

7

3

22

2

29

�

l .5

0 s

29.9

56.5

25.3

33.7

40.2

27.4

34.7

29.4

17.0

48.9

57.2

41.8

44.9

47.8

42.3

14.6

34.1

53.5

34.6

52.9

21.9

45.9

28.0

32.6

29.1

47.1

32.2

33.1

12.4

5.7

7.4

3.0

2.0

3.6

0.6

10.7

4.0

0.8

0.4

0.6

<1.0

<1.0

11.9

11.7

8.1

1.6

4.4

0.7

8.0

6.2

2.9

6.3

5.5

6.6

3.2

14.6

5.5

3.8

2.9

14.6

3.7

1.4

2.0

9.8

5.2

�

.

'§

0

0

2.4

1.2

4.6

7.9

1.6

4.1

1.0

2.1

1.3

0.5

2.3

�

·

2.9

1.7

0.1

0.4

5.1

3.4

0.6

0.3

0.5

0.8

r: Brien, N. R., and R. M. Sial I, 10, Argillaceous rock atlas, Sprger-Verlag, New York, Ta ble I, p. 12125.

Valu adjust lo 1 for shales of each age.

5.6

1.8

1.9

1.6

1.6

10.9

3.5

5.1

3.3

3.4

3.1

:

.5

0 s

<1.0

2.4

4.0

42.0

u

·

�

:

: 0

l �

l

0 u

0.9

2.6

1.4

0.4

3.5

2.0

10.9

0.3

0.2

1.0

4.7

3.7

1.5

4.5

142

Chapter 5 I Siliciclastic Sedimenta Rocks

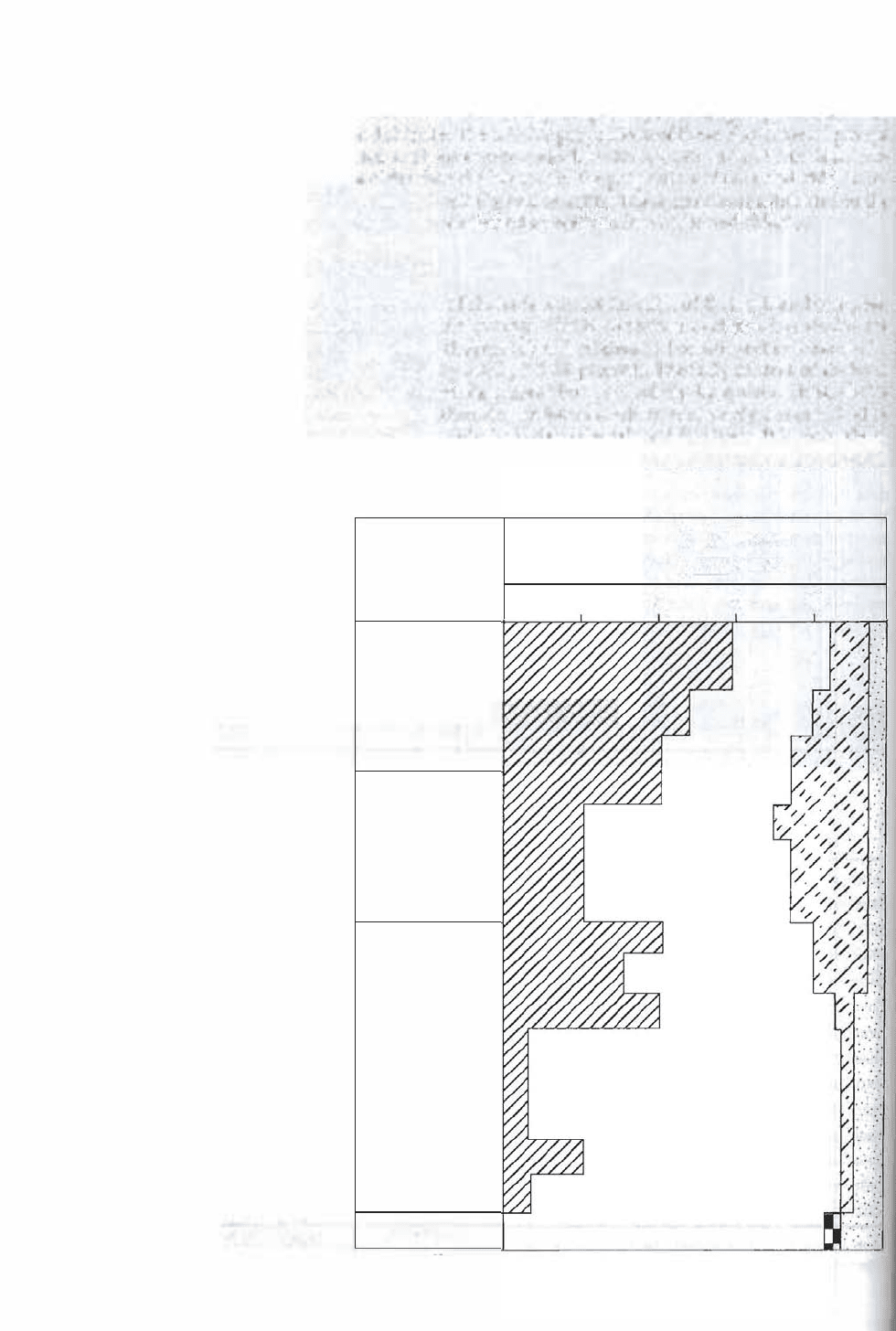

Fire 5.12

minerals, although some fraction of these minerals may also form during burial

diagenesis. particular, clay minerals appear to be strongly affected by diagenet

ic processes. As shown in Ta ble 5.1, the principal clay mineral groups are kaolinite,

illite, smectite, and chlorite. The relative proportions of these day-mineral groups

have been reported to change systematicaUy with age (Fig. 5.12). With time, par

ticularly in rocks older than the Mesozoic, the proporti011 of illite an chlorite in

creases at the expense of kaolinite and smectite. These trelds are attributed to the

diagenetic alteration of kaolinite and smeotte to form illite and chlorite.

Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of shales is a direct h.mction of their mineral composi

tion. Compositions of some average North American and Russian shales are

shown in Ta ble 5.6. Si02 is the most abundant chemical oonsttuent in these shales

(578 percent), followed by Al203 (16-19 percent). The Si02 content of shales is

affected by all silicate minerals prent but particularly by quartz. Thus, shales

tend to contain less Si02 than do sandstones, which commonly are enriched

quartz. Al203 is derived mainly from clay minerals and feldspars. It is more abun

dant in shales than in sandstones because of the greater clay mineral content of

Cenozoic

Mesozoic

Paleozoic

� smectite

illite

20

40

� kaolinite

chlorite

60 80

Systematic changes in relative abundance of

major clay minerals as a function of geologic

age. [After Singer, A., and G. Muller, 1983,

Diagenesis in argillaceous sediments, in Lar

son, G., and Chilingarian, G. V. (eds.), Dia

genesis in sediments and sedimentary rocks,

v. 2, Fig. 3.28, p. 176, reproduced by per

mission of Elsevier Science Publishers, New

York.]

Proterozoic

5.4 Shales (Mudrocks)

143

1

2

3 4

5

6 7 8 9

10

Si02

60.65

64.80

59.75

56.78

67.78

64.09

66.90 63.04 62.13

65.47

Al203

17.53

16.90

17.79

16.89

16.59

16.65

16.67

18.63

18.11

16.11

Fe203

7.11

F

5.66

5.59

6.56

4.11

6.03

5.87

7.66

7.33

5.85

MgO

2.04 2.86

4.02

4.56

3.38

2.54

2.59

2.60

3.57

2.50

CaO

0.52

3.63

6.10 8.91

3.91

5.65

0.53

1.31

2.22

4.10

NazO

1.47

1.14

0.72

0.77

0.98

1.27 1.50

1.02

2.68

2.80

KP

3.28

3.97

4.82

4.38

2.44

2.73

4.97

4.57

2.92

2.37

Ti0

2

0.97

0.70

0.98 0.92

0.70 0.82

0.78

0.94

0.78

0.49

P

2

0

s

0.13

0.13 0.12

0.13

0.10 0.12

0.14

0.10

0.17

MnO

0.10

0.06

0.08

0.07

0.06

0.12

1.10

0.07

u:

(1) Moore, 1978 (Pennsyh-anmn shale, lHinois Basin)

(2) Gromet et aL, 184 (North American shale composite)

{3) Ronov and .1igdisov, 1971 (average orth American Paleozoic shale)

(4) Ronov and Migdisov, 1971 (average Russian Paleozoic shale)

(5) Ronov and Migdisov, 1971 (average North American Mesozoic shale)

(6} Ronov and igdisov, 1971 (aYerage Russian Mesozoic shale}

(

71

Camer and Garrels, 1980 (averag(• Canadian Proterozoic shale)

{8) Ronov and Mtgdisov. 1971 (average Russian Proterozoic shale)

() Cameron and Garrels, 1980 (average Canadian Archean shale)

{10) Ronov and Migdisov, 1971 (average Arhean shale}

(11) Clarke, 1924 (average shale)

(l2i Shaw, 1956 (compilation of 155 analyses of shale)

(13) Av erage of alues in columns 1 through 12

shales. Fe in shales is supplied by iron oxide minerals (hematite, goethite), biotite,

and a few other minerals such as siderite, ankerite, and smectite day minerals.

K20 and MgO abundance is related mainly to day mineral abundance, although

some Mg may be supplied by dolomite and K is present in some feldspars. Na

abundance is related to the presence of clay minerals (e.g., smectites) and sodium

plaoclase. Ca is supplied by calcium-rich plagioclase and carbonate minerals

(calte, dolomite).

Classification

Because special analytical techniques are required to determine the mineral com

posion of shales, and because such techniques are time consuming and expen

sive, many geologists do not routinely determine the mineral composition of

shales (mudrocks). erefore, most classifications that have been proposed for

shales

have not been based on mineral composition, or at least not entirely on

meral composition. ese classifications, none of which has been widely accept

, commonly emphasize the relative amounts of silt and day, the hardness or de

e of induration of the rocks, and the presence or absence of fissile lamination.

(Fissility is defined as the property of a rock to split easily along thin, closely

spaced, approximately parallel layers.) Exceptions to this general practice of clas

sificaon are the classifications of Picard (1971), which emphasizes mineral com

position of the silt-size grains in mudrocks (shales), and the classification of

Lewan (1978), which requires semiquantitative X-ray diffraction analysis to deter

me mineralogy.

11

12

13

64.21

64.10

63.31

17.02 17.70

17.22

2.70

0.82

6.71

4.05

5.45

2.70

2.65

3.00

3.44

1.88

3.52

1.44

1.91 1.48

3.58

3.60

3.64

0.72

0.86

0.81

0. 10

0.05

0.06

144

Chapter 5 I Siliciclastic Sedimentary Rocks

�

�

B

z

�

z

�

�

�

:

�

�

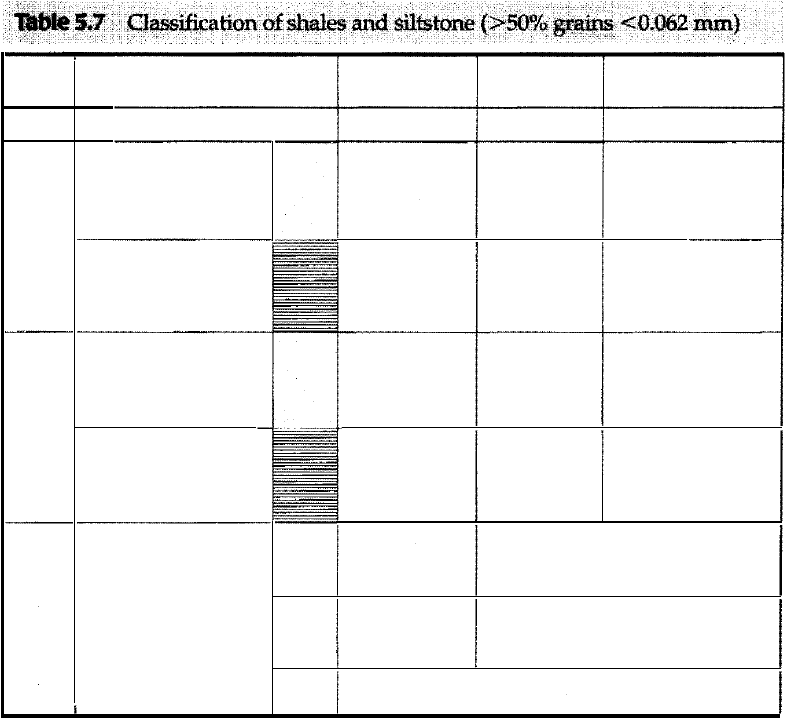

The classification of Potter, Maynard, and Pryor (1980), shown in Table 5.7, is

based on grain size, lamination, and degree of induration. It is similar to the field

classification of shales proposed by Lundegard and Samuels (1980). This classifi

cation emphasizes the importance of day-size constituents and bedding thickness,

that is, whether bedded or laminated. Depending upon these variables, shales can

be divided into mudstone (33-65% day-size constituents and bedded) or

mudshale (33-65% clay-size constituents and laminated), and claystone (66-100%

clay-size constituents and bedded) or clayshale (66-100% day-size constituents

and laminated). Fine-grained siliciclastic rocks that contain less than 33 percent

day-size constituents are siltstones.

Additional informal terms can be used with this classification to provide fur

ther information about the properties of the shales. These may include terms that

express color, type of cementation (calcareous, or limy; ferruginous, or iron-rich;

siliceous); degree of induration (hard, soft); mineralogy if known (e.g., quartzose,

feldspathic, micaceous); fossil content (e.g., fossiliferous, foram-rich); organic mat

ter content (e.g., carbonaceous, kerogen-rich, coaly); type of fracturing (con

choidal, hackly, blocky); or nature of bedding (e.g., wavy, lenticular, parallel).

Origin and Occurrence of Shales (Mudrocks)

Shales form under any environmental conditions in which fine sediment is abun

dant and water energy is sufficiently low to allow settling of suspended fine silt

Pe rcentage day-size

constituents

Field adjective

Beds

>lOmm

Laminae

<lOmm

Beds

>lOmm

Laminae

<lO mm

Low

e

.�

j

O

��

g�

I

e

High

32

Gritty

Bedded

silt

Laminated

silt

Bedded

siltstone

Laminated

siltstone

Quartz

Argillite

Quartz

Slate

335

66-100

Loamy

Fat or slick

Bedded

Bedded

mud

claymud

Laminated

Laminated

mud

claymud

Mudstone Claystone

Mudshale

Clays hale

Argillite

Slate

Phyllite and/ or Mica Schist

eo Potter. P E.,). B. Maynard, and W. . Pryor, 1980, imentology of sh aleso Springer-Ve rlag, New York, Ta ble 1.2, p. 14.