Blank B.E., Krantz S.G. Calculus: Single Variable

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

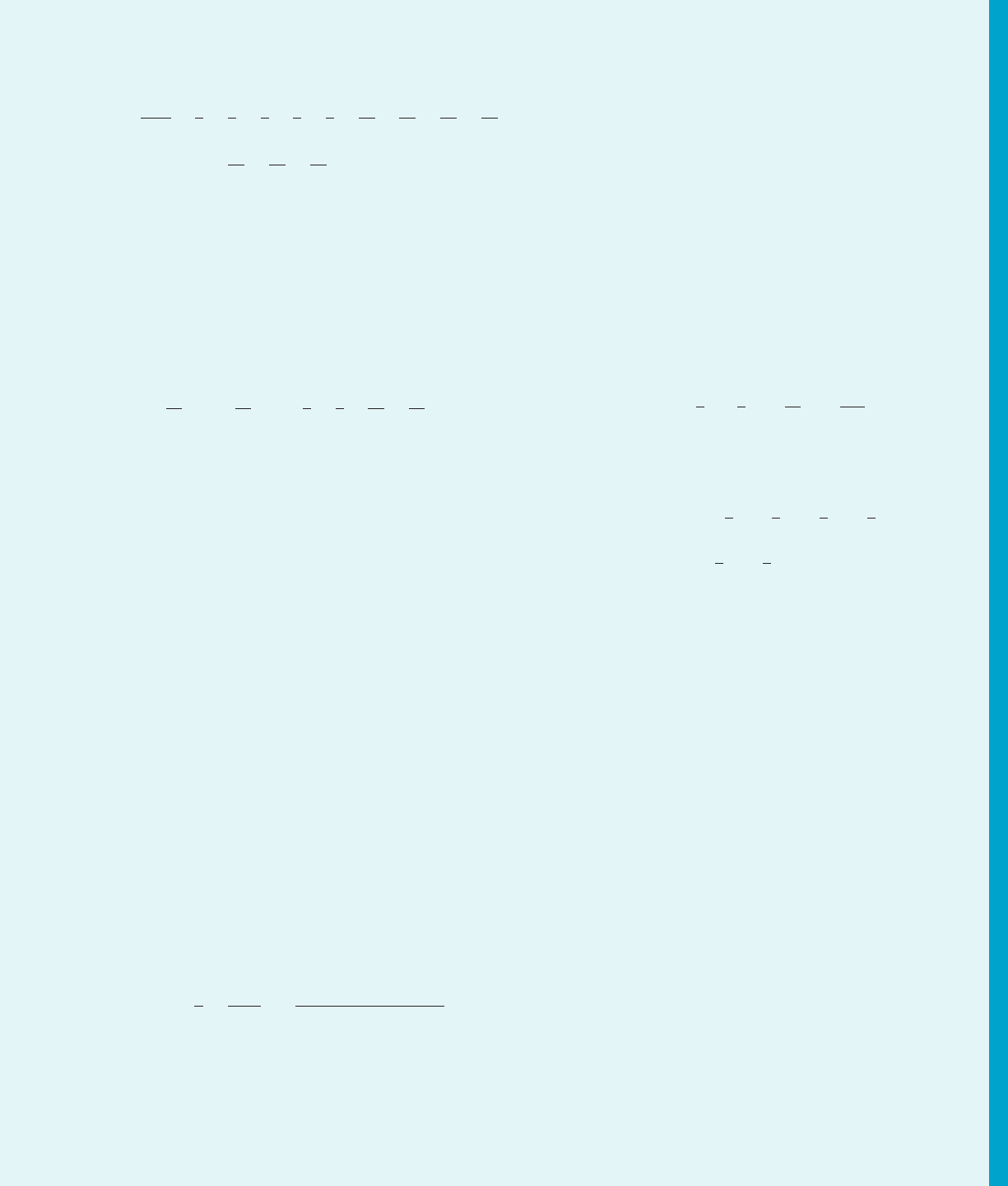

Estimating the

Remainder Term

(Section 8.8)

The remainder term R

N

satisfies the estimate

jR

N

ðxÞj# M

jx 2 cj

N11

ðN 1 1Þ!

where M is the maximum value of jf

(N 1 1)

(t)j for t between c and x. The Taylor

series T(x)off converges to f (x) if and only if R

N

(x) - 0asN-N.

Taylor’s theorem together with the error estimate may be used to approximate

the values of many transcendental functions to any desired degree of accuracy.

Taylor Series

Representations of

Common

Transcendental

Functions

(Section 8.8)

Many familiar functions have convergent power series representations. For

example,

sinðxÞ 5

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ð2n 1 1Þ!

x

2n11

5 x 2

1

3!

x

3

1

1

5!

x

5

2

1

7!

x

7

1

;

2N , x , N

cosðxÞ 5

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ð2nÞ!

x

2n

5 1 2

1

2!

x

2

1

1

4!

x

4

2

1

6!

x

6

1

;

2N , x , N

e

x

5

X

N

n50

1

n!

x

n

5 1 1 x 1

1

2!

x

2

1

1

3!

x

3

1

1

4!

x

4

1

1

5!

x

5

1

1

6!

x

6

1

;

2N , x , N:

The function f (x) 5 (1 1 x)

α

has a particularly interesting power series repre-

sentation called the binomial series:

ð1 1 xÞ

α

5

X

N

n50

α

n

x

n

for jxj, 1

where

α

n

5

α ðα 2 1Þðα 2 n 1 1Þ

n!

:

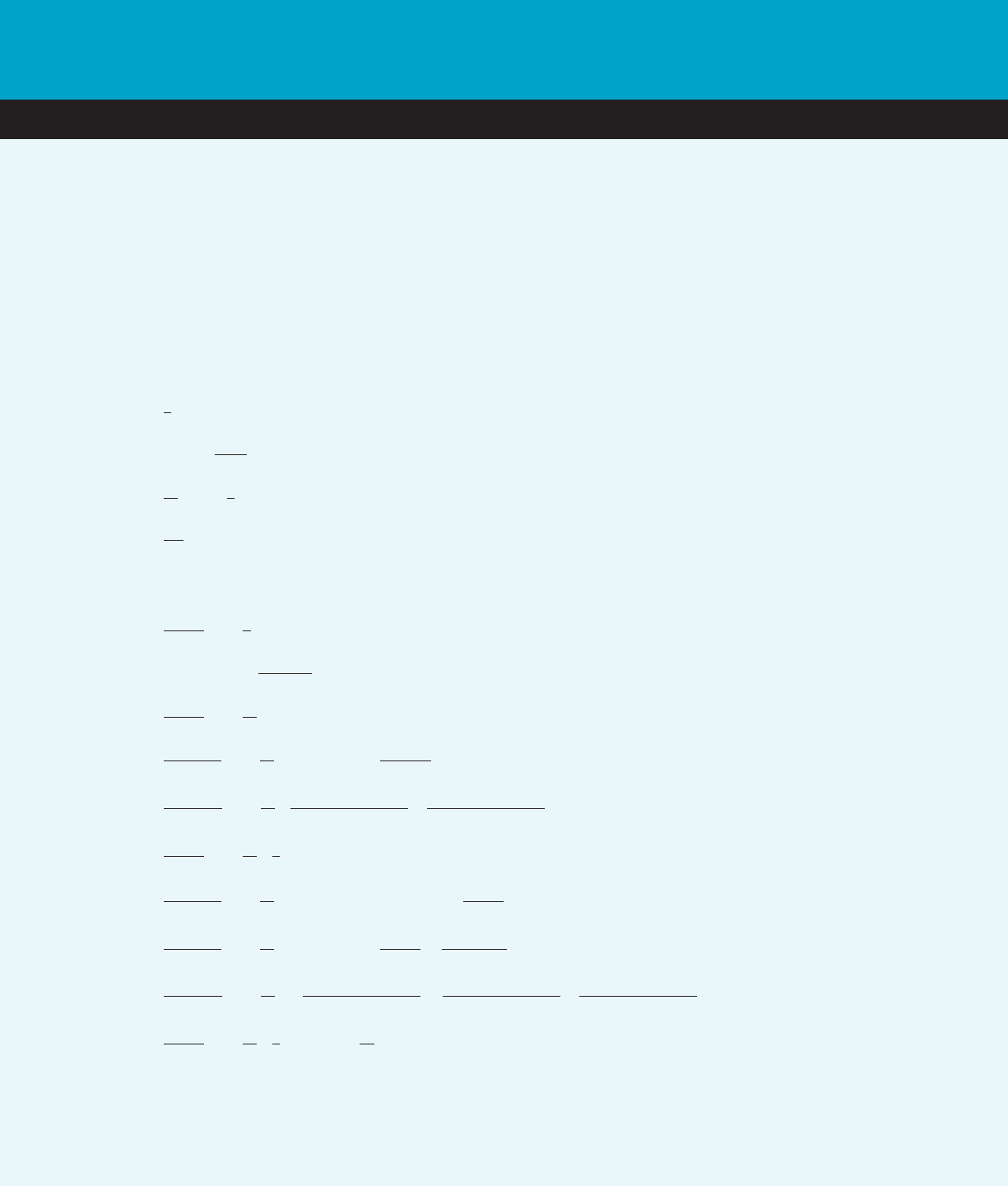

Review Exercises for Chapter 8

1. Calculate the first five partial sums S

1

, ..., S

5

of the series

P

N

n51

6n

ðn 1 1Þ

:

2. Calculate the first five partial sums S

1

,..., S

5

of the series

P

N

n51

n 2 2

n!

:

3. Evaluate

P

N

n50

ð3=5Þ

n

:

4. Evaluate

P

N

n51

4ð2=3Þ

n

:

5. Evaluate

P

N

n52

3

n11

=7

n21

:

6. Evaluate

P

N

n52

ð21=4Þ

n11

:

7. Express 0.6313636363 . . . as the ratio of two integers.

8. Express 0.183181818 . . . as the ratio of two integers.

c In Exercises 9244, determine if the given series converges

conditionally,

converges absolutely, or diverges. b

9.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 1

ffiffiffi

n

p

p

ð1 1

ffiffiffi

n

p

Þ

2

10.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

2

n

lnð2 1 nÞ

11.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

1

1 1 ð1=nÞ

2

12.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1

2 1 sinðnÞ

13.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

n

2

1 1

3

p

14.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

n

2

2

n

Review Exercises 715

15.

X

N

n52

ð21Þ

n11

n

2

ln

4

ðnÞ

16.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1

1 1

ffiffiffi

n

p

17.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1

1 1

ffiffiffi

n

p

1 n

ffiffiffi

n

p

18.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

5

n

n!

19.

X

N

n510

ð21Þ

n

1

nln

2

ðnÞ

20.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

7

n

2

3n

21.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n11

ffiffiffi

n

p

n 2

ffiffiffi

2

p

22.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

lnðnÞ

n

23.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

5

ð1 1 n

6

Þ

14=13

24.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

2

n

n

2

1 2

n

25.

X

N

n52

ð21Þ

n11

ln

2

ðnÞ

n

3=2

26.

P

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

sin

2

ð1=nÞ

27.

P

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

n sin

2

ð1=nÞ

28.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

n

29.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

n 1 ð1:3Þ

n

30.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

n

2=3

1 1 n

ffiffiffi

n

p

31.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

arctanðnÞ

n

ffiffiffi

n

p

32.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ð1:4Þ

n

n

3

1 ð1: 2Þ

n

33.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

1=n

34.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

ð

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

n

2

1 3n

p

2 nÞ

35.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

n 1 1

n

2

36.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

arccosð1=nÞ

n

37.

X

N

n52

ð21Þ

n11

1

lnðn

2

Þ

38.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

sin

1

n

csc

2

n

39.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

n13

2n 1 1

n

40.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

2 4 6 ð2nÞ

ðn!Þ

2

41.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n! 2

2n21

ð2n 2 1Þ!

42.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1 3 5 ð2n 1 1Þ

2 5 8 ð3n 1 2Þ

43.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n11

ðn!Þ

3

ð3nÞ!

44.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n!

n

n

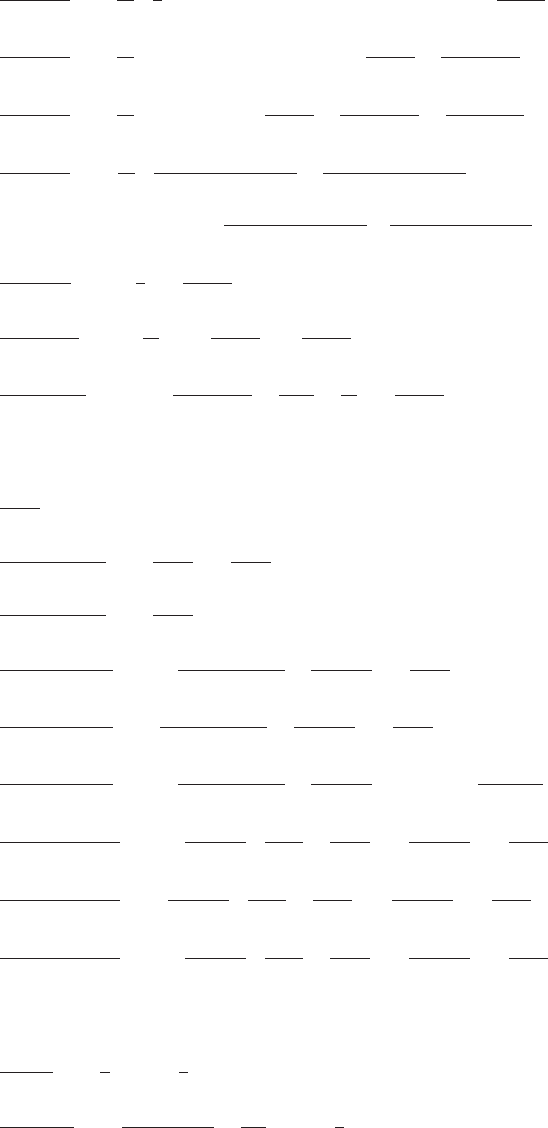

c In each of Exercises 45250, examine the given series and

use either the word conclusive or the word inconclusive to

complete each of the following two sentences. (a) The

Divergence Test applied to this series is __. (b) The Ratio Test

applied to this series is __. b

45.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

2

1 1

n

2

1 n

46.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

n

2

1 1

47.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

n

n

3

1 1

48.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

1

lnðn 1 1Þ

49.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

5

n

n

2

50.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

2

n

n

51. Estimate

P

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

4n

3

with an error no greater than

0.002.

52. Estimate

P

N

n50

ð22Þ

n

ð2nÞ!

with an error no greater than

0.0005.

53. Use the Integral Test to determine lower and upper

estimates for

P

N

n51

1

n

3=2

:

54. Use the Integral Test to determine lower and upper

estimates for

P

N

n51

2n 1 1

ðn

2

1 nÞ

2

.

c In Exercises 55266, determine the interval of convergence

of

the given power series. b

716 Chapter

8 Infinite Series

55.

P

N

n50

ð3x 1 4Þ

n

56.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n

ffiffiffi

n

p

x

3

n

57.

X

N

n50

3n

ðn 1 1Þ

3

x

n

58.

X

N

n51

ð1 1 1=nÞ

n

x

n

59.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

x

n

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

n

4=3

1 1

p

60.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

3

n

n

3

x

n

61.

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

ðx 1 1=2Þ

n

ffiffiffi

n

p

62.

X

N

n50

ð2 2 xÞ

n

2n 1 3

63.

X

N

n51

ð2x 1 3Þ

n

3

n

n

64.

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

ðx 1 1Þ

n

3n 1 1

65.

X

N

n52

ð21Þ

n

3

n

ln

2

ðnÞ

ð3x 2 1Þ

n

66.

X

N

n50

2

n

1 n

3

n

1 n

x 1

1

2

n

c In Exercises 67272, use the Maclaurin series for 1/(1 2 x)

together with algebra to find the Maclaurin series of the given

function. b

67.

2

3 1 x

68.

1

4 2 x

2

69.

27

81 2 x

4

70.

x

3

1 2 x

71.

x

2

1 1 x

2

72.

x

1 1 2x

c In each of Exercises 73276, approximate f (x)

at the

indicated value of x by using a Taylor polynomial of order 2

and given base point c. Use formula (8.8.3) of Theorem 1 to

express the error resulting from this approximation in terms

of a number s between c and x. b

73.

f ðxÞ5 x 2

12x

x 5 5=4 c 5 1

74.

f ðxÞ5 xe

2x

x 5 1=2 c 5 0

75. f ðxÞ5 3 2 cosðxÞ x 5 π=2 c 5 π=3

76.

f ðxÞ5

ffiffiffi

2

p

sinðxÞ x 5 π=8 c 5 π=4

c In each of Exercises 77280,

a function f, a base point c,

and a point x

0

are given.

a. Calculate

the approximation T

3

(x

0

)off (x

0

).

b. Use inequality (8.8.7) to find an upper bound for the

absolute error jR

3

(x

0

)j5 jf (x

0

)2T

3

(x

0

)j that results from

the approximation of part (a). b

77. f ðxÞ5

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ffi

4 1 x

p

½c; x

0

5 ½0; 0:41

78. f ðxÞ5 1=x ½x

0

; c5 ½1=4; 1=2

79. f ðxÞ5 x 1 expð2xÞ½cx

0

5 ½0; 1=2

80. f ðxÞ5 lnðxÞ½x

0

; c5 ½e 2 1=2; e

c In Exercises 81284, use a Taylor polynomial to calculate

the

given integral with an error less than 10

23

. b

81.

R

0:2

0

sinðx

2

Þ dx

82.

R

0:2

0

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 1

1

2

x

3

r

dx

83.

Z

0:2

0

1

1 1 x

3

dx

84.

R

0:1

0

e

22x

2

dx

c In Exercises 85287,

use power series to calculate the

requested limit. b

85. lim

x-0

expðxÞ1 expð2xÞ2 2

x

2

:

86. lim

x-0

2 2 2cosðxÞ2 x

2

x

4

:

87. lim

x-0

xarctanðx

2

Þ

x 2 sinðxÞ

:

88. lim

x-0

expð2xÞ2 expð22xÞ

expð3xÞ2 expð23xÞ

:

Review Exercises 717

GENESIS

&

DEVELOPMENT8

Infinite Series in Ancient Greece

The concept of infinite series, like many of the mathe-

matical ideas that we study today, originated in ancient

Greece. Zeno’s Arrow paradox, which was posed in the

5th century B.C.E., arises from decomposing the num-

ber 1 into infinitely many summands by means of the

geometric series, 1 5 1/2 1 1/4 1 1/8 1 1/16 1

...

.Two

hundred years later, Archimedes, who worked precisely

and confidently with infinite processes, used the formula

1 1 1/4 1 1/16 1 1/64 1 1/256 1 5 4/3 to calculate the

area of a parabolic sector.

Nicole Oresme

With the decline of Greek mathematics, the study of

infinite series was put on hold. Progress resumed in the

Middle Ages. Nicole Oresme (ca. 13201382) was one

of the greatest of the medieval philosophers. Trained in

theology, Oresme abandoned an academic career to rise

through the ranks of the clergy, obtaining a Bishop’s

chair in 1377. Along the way, he served as financial

advisor to France’s King Charles V. In response to a

request from Charles, Oresme translated severa l of

Aristotle’s works from Latin into French. These

translations are considered to have had an important

influence on the development of the French language.

Oresme’s own writings were both extensive and

varied. He is commonly held to be the leading econo-

mist of the Middle Ages—one can make a case for a

similar status in physics. But it is Oresme’ s work in

mathematics that is best known today. It was Oresme

who first demonstrated that an infinite series can be

divergent even though its terms converge to 0. (The

proof of the divergence of the harmonic series that is

found in Section 8.1 is that of Oresme.) Oresme also

found a clever way to show that

P

N

n51

n

2

n21

5 4.

Oresme turned out to be something of an isolated

genius in medieval mathematics. He had no immediate

followers to develop his theories and extend his

mathematical work. Not all of Oresme’s work sank into

oblivion, but his work on infinite series certainly did.

M

¯

adhavan

The Indian mathematician M¯adhavan (13501425), a

near-contemporary of Oresme, also discovered

remarkable facts about infinite series. M¯adhavan’s

work was even more overlooked than that of Oresme

and remained largely unknown until its recognition

midway through the 20th century. Two examples will

suffice to show M ¯adhavan’s depth and originality:

π

ffiffiffiffiffi

12

p

5

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1

ð2n 1 1Þ3

n

5 1 2

1

3 3 3

1

1

5 3 3

2

2

1

7 3 3

3

1

:::

and

π

4

5

X

N

n50

ð21Þ

n

1

ð2n 1 1Þ

5 1 2

1

3

1

1

5

2

1

7

1

::::

The simplicity of this second formula, which relates the

circular ratio π to the odd integers, is strik ing. With the

methods learned in Chapter 8, we know how to derive

such formulas, but historians do not know how

M¯adhavan himself obtained them—mathematicians

who followed M¯a dhavan recorded only the statements

of his main theorems. Nothing of M ¯adhavan’s own

mathematical writing has survived.

Infinite Series in the 17th Century

The study of infinite series began to flourish in the 17th

century. Pietro Mengoli (16261686) found the value

of the alternating harmonic series,

lnð2Þ5

X

N

n51

ð21Þ

n11

1

n

5 1 2

1

2

1

1

3

1

1

4

2

1

5

1

:::;

as did several other mathematicians. Mengoli also

reproved Oresme’s forgotten theorem concerning the

divergence of the harmonic series. M¯adhavan’s work

did not become known in the West until modern times,

but his infinite series for π/4 was rediscovered in the

second half of the 17th century. In a 1676 letter to

Newton, Leibniz communicated the formula π/4 5

1 2 1/3 1 1/5 2 1/7 1 . . . , the right side of which is now

called Leibniz’s series. Newton, who had previously

obtained similar results, responded with an astonishing

example of scientific one-upmanship. Providing only

the sketchiest of hints, Newton sent Leibniz an analo-

gous but much less transparent series involving π and

the odd natural numbers:

718

π

2

ffiffiffi

2

p

5

1

1

1

1

3

2

1

5

2

1

7

1

1

9

1

1

11

2

1

13

2

1

15

1

1

17

1

1

19

2

1

21

2

1

23

1 ::: :

Euler

A contemporary of the 18th century mathematician,

Leonhard Euler, once remarked that Euler calculated as

effortlessly as “men breathe, as eagles sustain themselves

in the air.” Euler was a master of both convergent and

divergent infinite series. One of his earliest successes was

the evaluation of a series that eluded his predecessors:

π

2

6

5

X

N

n51

1

n

2

5 1 1

1

4

1

1

9

1

1

16

1

1

25

1

::::

In fact, Euler discovered a method to evaluate all p-series

ζðpÞ5

P

N

n51

n

2p

for which p is a positive even integer.

More precisely, Euler was able to determine rational

numbers q

k

such that ζð2kÞ5 q

k

π

2k

for each positive

integer k. For example, q

1

5 1/6, ζ(2) 5 π

2

/6, q

2

5 1/90,

ζ(4) 5 π

4

/90, and q

3

5 1/945, ζ(6) 5 π

6

/945. The numera-

tors of q

1

through q

5

are all 1, but that pattern ends with

q

6

. Euler calculated explicitly as far as q

13

5 1315862/

11094481976 0305 78125.

The function ζ( p) is called the zeta function, after

the Greek letter by which it is usually denoted. Given

our knowledge of ζ(2), ζ(4), ζ(6), and so on, it is natural

to wonder about ζ(3). To this day, the p-series

P

N

n51

1=n

2k11

with odd exponents remain mysterious.

In 1978, Roger Ap

´

ery (19161994) created a sensation

when he proved that ζ(3) is irrational. Despite a great

deal of effort since then, we do not know the exact

value of ζ(3) or of any other odd power p-series.

An Infinite Series of Ramanujan

The formula of M¯adhavan and Leibniz can be used to

calculate the digits of π, but it is a very inefficient

procedure. Sum 1,000 terms of Leibniz’s series, and you

do not even get the third decimal place of π for your

effort. The grade school approximation 22/7 is very

nearly as accurate. Compare that with the formula

1

π

5

ffiffiffi

8

p

9801

X

N

n50

ð4nÞ!ð1103 1 26390nÞ

ðn!Þ

4

ð396Þ

4n

that the Indian mathematician, Srinivasa Ramanujan

(18871920), found early in the 20th century. Sum just

the first two terms of this series, and you obtain

0.3183098861837906, every digit of which agrees with

that of 1/π. Ever since Ramanujan’s untimely death,

mathematicians have been at work analyzing and

proving the mysterious equations that filled his

notebooks.

The Early History of Power Series

Before the general theory of Taylor series was devel-

oped, many particular power series expansions were

discovered and rediscovered. For example, in 1624,

Henry Briggs (15611631) derived the power series

formula

ð1 1 xÞ

1=2

5 1 1

1

2

x 2

1

8

x

2

1

1

16

x

3

2

5

128

x

4

1

:::

in the course of calculating logarithms. This formula of

Briggs is a special case of the binomial series. The

Maclaurin series of ln(1 1 x)

lnð1 1 xÞ5 x 2

1

2

x

2

1

1

3

x

3

2

1

4

x

4

1

1

5

x

5

2

1

6

x

6

1

1

7

x

7

2

:::;

was independently discovered by Johann Hudde

(16281704) in 1656, by Sir Isaac Newton in 1665, and

by Nicolaus Mercator (c. 16191687) in 1668.

James Gregory and Sir Isaac Newton

Newton derived the binomial series as well as several

other power series in 1665. These series played an

important role in his first approach to calculus. Early in

the 1670s, Newton began to correspond with the Scot-

tish mathematician, James Gregory. By 1671, Gregory

had obtained the Maclaurin series for arcsin(x),

arctan(x), tan(x), and sec(x). Until then, the series that

had been discovered—Newton’s binomial series and

the power series for the logarithm, the arcsine, and the

arctangent, in particular—had all been derived by

special techniques. An analysis of Gregory’s private

papers, however, reveal that Gregory hit upon the idea

of Taylor series in the early 1670s and used the con-

struction to derive the power series expansions of

tan(x) and sec(x). It is likely that Gregory, thinking that

he had rediscovered a method already known to

Newton, withhel d publication of his discovery of Taylor

series in order to cede the privilege of first publication

Genesis & Developement 719

to Newton. In fact, Newton did not discover Taylor

series until 1691 and that discovery, hidden in his pri-

vate papers, did not come to light until 1976!

Brook Taylor (16851731)

Brook Taylor was born into a well-to-do family with

connections to the nobility. Although he studied law at

Cambridge, his scientific career was already under way

by the time he graduated. Encouraged by contacts at

the Royal Society to develop and communicate his

discoveries, Tay lor privately disclosed the series that

now bears his name in a letter of 1712. He first publicly

communicated his work on series in his book, The

Method of Increments, which appeared in 1715. At the

time, the unpublished work of Gregory and Newton

remained unknown. Johann Bernoulli and Abraham

De Moivre had published anticipations of Taylor series

in 1694 and 1708, but they did not deny Tay lor’s claim

to priority. Moreover, Taylor’s immediate successors,

including Maclaurin and Euler, credited him not only

for introducing Taylor series, but also for demonstrat-

ing the uses to which they can be put. The term Taylor

series has been traced to 1786, after which it quickly

became established. By the mid-1800s, one writer

commented, “A single analytical formula in the

Method of Increments has conferred a celebrity on its

author, which the most voluminous works have not

often been able to bestow.” It is ironic, then, that

Taylor series were known to Gregory fourteen years

before Taylor was born and the error term, which is a

crucial compo nent of Taylor’s Theorem in practice, was

introduced by Lagrange several years after Taylor’s

death.

Colin Maclaurin (16981746)

Colin Maclaurin was born a minister’s son. Orphaned

at the age of nine, he became the ward of an uncle, who

was also a minister. The precocious boy entered the

University of Glasgow just two years later. The plan

was that he too would become a minister. At the age of

twelve, however, Maclaurin discovered the Elements of

Euclid and was led astray. Within a few days he mas-

tered the first six books of Euclid. His interest in

mathematics did not wane thereafter. Three years later,

at the age of fifteen, he defended his thesis on Gravity

and graduated from university.

The young Maclaurin had to bide his time for a few

years, but he was still only nineteen when, in 1717, he

was appointed Professor of Mathematics at the Uni-

versity of Aberdeen. In the next two years, he forged a

warm friendship with Sir Isaac Newton, a bond that

Maclaurin described as his “greatest honour and hap-

piness.” On Newton’s recommendation, the University

of Edinburgh offered Maclaurin a professorship in

1725. It came in the nick of time—Aberdeen was about

to dismiss Maclaurin for being absent without leave for

nearly three years. His teaching at Edinburgh had

happier results. One student wrote that “He made

mathematics a fashionable study.”

Maclaurin’s research also received the highest

praise. Lagrange described Maclaurin’s study of tides

as “a masterpiece of geometry, comparable to the most

beautiful and ingenious results that Archimedes left to

us.” Maclaurin’s Treatise of Fluxions, which appeared

in 1742, is considered his major work. He conceived it

as an answer to the criticisms of Bishop Berkeley that

have been discussed in Genesis and Development 2 and

3. Although Maclaurin series are to be found in the

Treatise of Fluxions, Maclaurin himself attributed them

to Taylor. Thus the terminology Maclaurin series is not

historically justified. Nonetheless, it is convenient—it

saves us from having to say “Taylor series expanded

about 0.” Furthermore, it is appropriate to remember

this great mathematician in some way. Ideas such as the

Integral Test that Maclaurin did introduce in his

Treatise do not be ar his name.

720 Chapter 8 Infinite Series

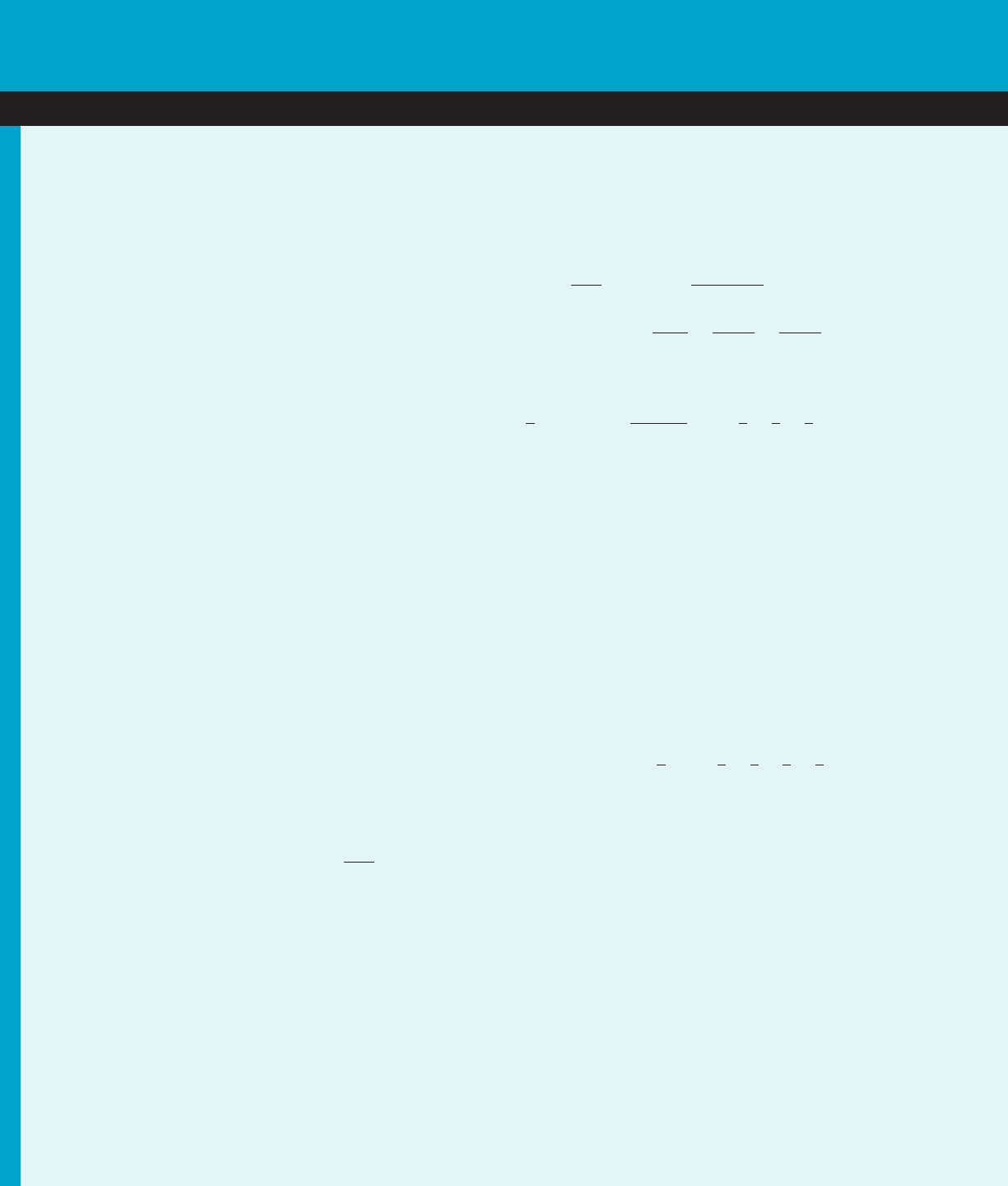

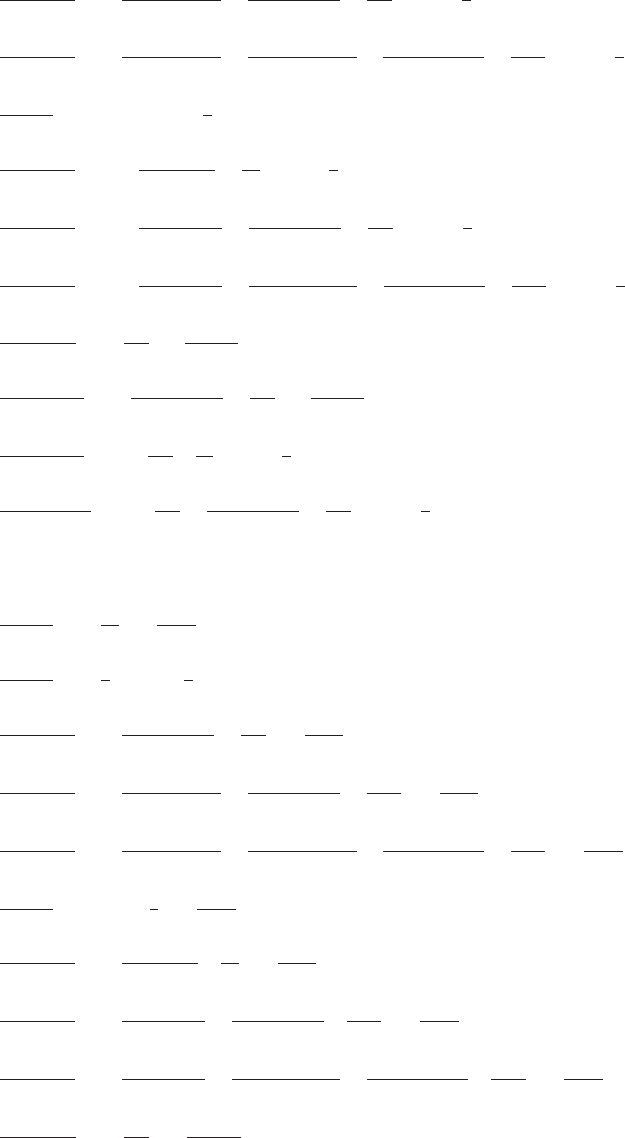

Table of Integrals

Integrals Involving x

p

1.

Z

1

x

dx 5 lnð x

jjÞ

1 C

2.

Z

x

p

dx 5

1

p 1 1

x

p11

1 C; ðp 6¼ 21Þ

3.

Z

1

x

2

dx 52

1

x

1 C

4.

Z

1

ffiffiffi

x

p

dx 5 2

ffiffiffi

x

p

1 C

Integrals Involving a 1 bx

5.

Z

1

a 1 bx

dx 5

1

b

lnð a 1 bx

jjÞ

1 C

6.

Z

ða 1 bxÞ

p

dx 5

1

ðp 1 1Þb

ða 1 bxÞ

p11

1 C; ðp 6¼ 2 1Þ

7.

Z

x

a 1 bx

dx 5

1

b

2

ða 1 bxÞ2 a lnð a 1 bxjjÞ

1 C

8.

Z

x

ða 1 bxÞ

2

dx 5

1

b

2

lnð a 1 bx

jjÞ

1

a

ða 1 bxÞ

1 C

9.

Z

x

ða 1 bxÞ

p

dx 5

1

b

2

a

ðp 2 1Þða 1 bxÞ

p21

2

1

ðp 2 2Þða 1 bxÞ

p22

1 C; ðp 6¼ 1; 2Þ

10.

Z

x

2

a 1 bx

dx 5

1

b

3

1

2

ða 1 bxÞ

2

2 2aða 1 bxÞ1 a

2

lnð a 1 bxjjÞ

1 C

11.

Z

x

2

ða 1 bxÞ

2

dx 5

1

b

3

ða 1 bxÞ2 2a lnð a 1 bx

jjÞ

2

a

2

a 1 bx

1 C

12.

Z

x

2

ða 1 bxÞ

3

dx 5

1

b

3

lnð a 1 bx

jjÞ

1

2a

a 1 bx

2

a

2

2ða 1 bxÞ

2

1 C

13.

Z

x

2

ða 1 bxÞ

p

dx 5

1

b

3

2

a

2

ðp 2 1Þða 1 bxÞ

p21

1

2a

ðp 2 2Þða 1 bxÞ

p22

2

1

ðp 2 3Þða 1 bxÞ

p23

1 C; ðp 6¼ 1; 2; 3Þ

14.

Z

x

3

a 1 bx

dx 5

1

b

4

1

3

ða 1 bxÞ

3

2

3a

2

ða 1 bxÞ

2

1 3a

2

ða 1 bxÞ2 a

3

ln

a 1 bxjj

1 C

T-1

15.

Z

x

3

ða 1 bxÞ

2

dx 5

1

b

4

1

2

ða 1 bxÞ

2

2 3aða 1 bxÞ1 3a

2

ln

a 1 bxjj

1

a

3

a 1 bx

1 C

16.

Z

x

3

ða 1 bxÞ

3

dx 5

1

b

4

ða 1 bxÞ2 3a ln

a 1 bx

jj

2

3a

2

a 1 bx

1

a

3

2ða 1 bxÞ

2

1 C

17.

Z

x

3

ða 1 bxÞ

4

dx 5

1

b

4

ln

a 1 bx

jj

1

3a

a 1 bx

2

3a

2

2ða 1 bxÞ

2

1

a

3

3ða 1 bxÞ

3

1 C

18.

Z

x

3

ða 1 bxÞ

p

dx 5

1

b

4

a

3

ðp 2 1Þða 1 bxÞ

p21

2

3a

2

ðp 2 2Þða 1 bxÞ

p22

1

3a

ðp 2 3Þða 1 bxÞ

p23

2

1

ðp 2 4Þða 1 bxÞ

p24

1 C; ðp 6¼ 1; 2; 3; 4Þ

19.

Z

1

xða 1 bxÞ

dx 52

1

a

ln

a 1 bx

x

1 C

20.

Z

1

xða 1 bxÞ

2

dx 52

1

a

2

ln

a 1 bx

x

1

bx

a 1 bx

1 C

21.

Z

1

x

2

ða 1 bxÞ

2

dx 52b

1

a

2

ða 1 bxÞ

1

1

a

2

bx

2

2

a

3

ln

a 1 bx

x

1 C

Integrals Involving x 1 a and x 1 b, a 6¼b

22.

Z

x 1 a

x 1 b

dx 5 x 1 ða 2 bÞln ð x 1 bÞ1 C

23.

Z

1

ðx 1 aÞðx 1 bÞ

dx 5

1

a 2 b

ln

x 1 b

x 1 a

1 C

24.

Z

x

ðx 1 aÞðx 1 bÞ

dx 5

1

a 2 b

aln

x 1 a

jj

2 b ln

x 1 b

jj

1 C

25.

Z

1

ðx 1 aÞðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 52

1

ða 2 bÞðx 1 bÞ

1

1

ða 2 bÞ

2

ln

x 1 a

x 1 b

1 C

26.

Z

x

ðx 1 aÞðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 5

b

ða 2 bÞðx 1 bÞ

2

a

ða 2 bÞ

2

ln

x 1 a

x 1 b

1 C

27.

Z

x

2

ðx 1 aÞðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 52

b

2

ða 2 bÞðx 1 bÞ

1

a

2

ða 2 bÞ

2

lnð x 1 a

jjÞ

1

b

2

2 2ab

ða 2 bÞ

2

lnð x 1 b

jjÞ

1 C

28.

Z

1

ðx 1 aÞ

2

ðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 52

1

ða 2 bÞ

2

1

x 1 a

1

1

x 1 b

1

2

ða 2 bÞ

3

ln

x 1 a

x 1 b

1 C

29.

Z

x

ðx 1 aÞ

2

ðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 5

1

ða 2 bÞ

2

a

x 1 a

1

b

x 1 b

2

ða 1 bÞ

ða 2 bÞ

3

ln

x 1 a

x 1 b

1 C

30.

Z

x

2

ðx 1 aÞ

2

ðx 1 bÞ

2

dx 52

1

ða 2 bÞ

2

a

2

x 1 a

1

b

2

x 1 b

1

ð2abÞ

ða 2 bÞ

3

ln

x 1 a

x 1 b

1 C

Integrals Involving a

2

1 x

2

31.

Z

1

a

2

1 x

2

dx 5

1

a

arctan

x

a

1 C

32.

Z

1

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

dx 5

x

2a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

1

2a

3

arctan

x

a

1 C

T-2 Table of Integrals

33.

Z

1

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

3

dx 5

x

4a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

1

3x

8a

4

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

3

8a

5

arctan

x

a

1 C

34.

Z

1

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

4

dx 5

x

6a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

3

1

5x

24a

4

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

1

5x

16a

6

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

5

16a

7

arctan

x

a

1 C

35.

Z

x

2

a

2

1 x

2

dx 5 x 2 a arctan

x

a

1 C

36.

Z

x

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

dx 52

x

2ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

1

2a

arctan

x

a

1 C

37.

Z

x

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

3

dx 52

x

4ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

1

x

8a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

1

8a

3

arctan

x

a

1 C

38.

Z

x

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

4

dx 52

x

6ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

3

1

x

24a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

1

x

16a

4

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

1

16a

5

arctan

x

a

1 C

39.

Z

1

xða

2

1 x

2

Þ

dx 5

1

2a

2

ln

x

2

a

2

1 x

2

1 C

40.

Z

1

xða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

dx 5

1

2a

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

1

1

2a

4

ln

x

2

a

2

1 x

2

1 C

41.

Z

1

x

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

dx 52

1

a

2

x

2

1

a

3

arctan

x

a

1 C

42.

Z

1

x

2

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

dx 52

1

a

4

x

2

x

2a

4

ða

2

1 x

2

Þ

2

3

2a

5

arctan

x

a

1 C

Integrals Involving a

2

2 x

2

43.

Z

1

a

2

2 x

2

dx 5

1

2a

ln

x 1 a

x 2 a

1 C

44.

Z

1

a

2

2 x

2

dx 5

1

a

tanh

21

x

a

1 C

45.

Z

1

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

dx 5

x

2a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

1

1

4a

3

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

46.

Z

1

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

3

dx 5

x

4a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

1

3x

8a

4

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

1

3

16a

5

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

47.

Z

1

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

4

dx 5

x

6a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

3

1

5x

24a

4

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

1

5x

16a

6

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

1

5

32a

7

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

48.

Z

x

2

a

2

2 x

2

dx 52x 1

a

2

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

49.

Z

x

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

dx 5

x

2ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

1

4a

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

50.

Z

x

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

3

dx 5

x

4ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

2

x

8a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

1

16a

3

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

51.

Z

x

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

4

dx 5

x

6ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

3

2

x

24a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

2

x

16a

4

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

1

32a

5

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

52.

Z

1

xða

2

2 x

2

Þ

dx 5

1

2a

2

ln

x

2

a

2

2 x

2

1 C

Integrals Involving a

2

2 x

2

T-3

53.

Z

1

xða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

dx 5

1

2a

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

1

1

2a

4

ln

x

2

a

2

2 x

2

1 C

54.

Z

1

x

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

dx 52

1

a

2

x

1

1

2a

3

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

55.

Z

1

x

2

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

2

dx 52

1

a

4

x

1

x

2a

4

ða

2

2 x

2

Þ

1

3

4a

5

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1 C

Integrals Involving a

4

6 x

4

56.

Z

1

a

4

1 x

4

dx 5

1

4a

3

ffiffiffi

2

p

ln

x

2

1 ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

1 a

2

x

2

2 ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

1 a

2

1

1

2a

3

ffiffiffi

2

p

arctan

ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

a

2

2 x

2

1 C

57.

Z

x

a

4

1 x

4

dx 5

1

2a

2

arctan

x

2

a

2

1 C

58.

Z

x

2

a

4

1 x

4

dx 52

1

4a

ffiffiffi

2

p

ln

x

2

1 ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

1 a

2

x

2

2 ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

1 a

2

1

1

2a

ffiffiffi

2

p

arctan

ax

ffiffiffi

2

p

a

2

2 x

2

1 C

59.

Z

1

a

4

2 x

4

dx 5

1

4a

3

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

1

1

2a

3

arctan

x

a

1 C

60.

Z

x

a

4

2 x

4

dx 5

1

4a

2

ln

a

2

1 x

2

a

2

2 x

2

1 C

61.

Z

x

2

a

4

2 x

4

dx 5

1

4a

ln

a 1 x

a 2 x

2

1

2a

arctan

x

a

1 C

Integrals Involving

ffiffiffi

x

p

and a

2

6 b

2

x

62.

Z

1

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

ffiffiffi

x

p

dx 5

2

ab

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

63.

Z

1

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

dx 5

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

2

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

1

1

a

3

b

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

64.

Z

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

2

1 b

2

x

dx 5

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

2

2

2a

b

3

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

65.

Z

ffiffiffi

x

p

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

2

dx 52

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

2

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

1

1

ab

3

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

66.

Z

x

3=2

a

2

1 b

2

x

dx 5

2x

3=2

3b

2

2

2a

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

4

1

2a

3

b

5

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

67.

Z

x

3=2

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

2

dx 5

2x

3=2

b

2

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

1

3a

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

4

ða

2

1 b

2

xÞ

2

3a

b

5

arctan

b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

1 C

68.

Z

1

ða

2

2 b

2

xÞ

ffiffiffi

x

p

dx 5

1

ab

ln

a 1 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a 2 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

1 C

69.

Z

1

ða

2

2 b

2

xÞ

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

dx 5

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

2

ða

2

2 b

2

xÞ

1

1

2a

3

b

ln

a 1 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a 2 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

1 C

70.

Z

ffiffiffi

x

p

a

2

2 b

2

x

dx 52

2

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

2

1

a

b

3

ln

a 1 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a 2 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

1 C

71.

Z

ffiffiffi

x

p

ða

2

2 b

2

xÞ

2

dx 5

ffiffiffi

x

p

b

2

ða

2

2 b

2

xÞ

2

1

2ab

3

ln

a 1 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

a 2 b

ffiffiffi

x

p

1 C

T-4 Table of Integrals