Ball Martin, M?ller Nicole. The Celtic Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

656 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

Welsh was now established as a written medium and the printed word gave it prestige

and status in the eyes of its speakers. It is estimated that between 1546 and 1695 a total

of 170 books were printed in Welsh. During the next 22 years up to 1718 a total of 126

were published, and during the next 22 years the total increased to 250 books. The nine-

teenth century saw a proliferation of published material in Welsh, ranging from books

to periodicals and weekly newspapers. In 1896 it is estimated that thirty-two periodicals

and twenty-fi ve newspapers were published in Welsh. Hughes & Son (Publishers) tes-

tifi ed to the Cross Commission 1886–7 that at least £100,000 per annum was spent on

Welsh- language publications (see Edwards 1987: 122). All these were aimed at the ordi-

nary reader. Welsh was fi rmly established as the language of literacy.

Religious zeal and fervour resulted in theological publications in Welsh and with the

Methodist revival in the eighteenth century came one of the greatest literacy drives in

Europe. Griffi th Jones’s circulating schools taught many of the Welsh peasantry the rudi-

ments of reading so that they could read the Word of God in their own homes. By 1761,

the year of the founder’s death, approximately 3,495 schools had been held and 158,000

educated in the skills of reading in Welsh. A letter written by Griffi th Jones on 11 October

1739 throws light on the fact that his schools were Welsh medium: ‘May we therefore not

justly fear when we attempt to abolish a language . . . that we fi ght against the decrees of

heaven and seek to undermine the disposals of divine providence’ (quoted in R. T. Jones

1973: 68). In Griffi th Jones’s eyes, to maintain Welsh- medium schools was to respect

God’s will – it was a religious obligation! With the spread of the Methodist movement and

the numerous religious revivals which characterized Wales in the eighteenth and nine-

teenth centuries, Christianity became the dominant interest and force in Welsh life. Local

social life revolved around the chapel. Between 1800 and 1850 chapels were put up at the

rate of one a fortnight. Preaching festivals drew large crowds and theological discussions

were not confi ned to places of worship. All this gave a boost to the language because the

religious domain was not only important, affecting all aspects of people’s lives, but was

also of high status. Religious observances and practices gave the faithful a solid linguis-

tic education by expanding their range of registers. Through preaching, ordinary people

became acquainted not only with religious terminology, but with public and formal modes

of address. They became acquainted with a spoken literary variety of Welsh. Through the

mid- week meetings and Sunday schools they were given an opportunity to communicate

orally in a less formal situation while at the same time being educated in the literary writ-

ten language through the reading and writing activities. Life could be lived fully in Welsh,

in spite of the fact that it did not have offi cial recognition and also in spite of the fact that

it was an expression of social class.

GEOLINGUISTICS: THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Geolinguistics is the study of language in spatial context.

5

Thomas Darlington (1894,

quoted in Rhys and Jones 1900: 548) was of the opinion that in 1801 approximately 80

per cent of the population of Wales spoke Welsh. The other 20 per cent were restricted

mostly to certain towns, and areas such as South Pembroke, Gower and along the border

with England. Ernest Georg Ravenstein (1879, quoted in Rhys and Jones 1900: 548–9)

estimated that 66.2 per cent of the population of Wales spoke Welsh in the early 1870s.

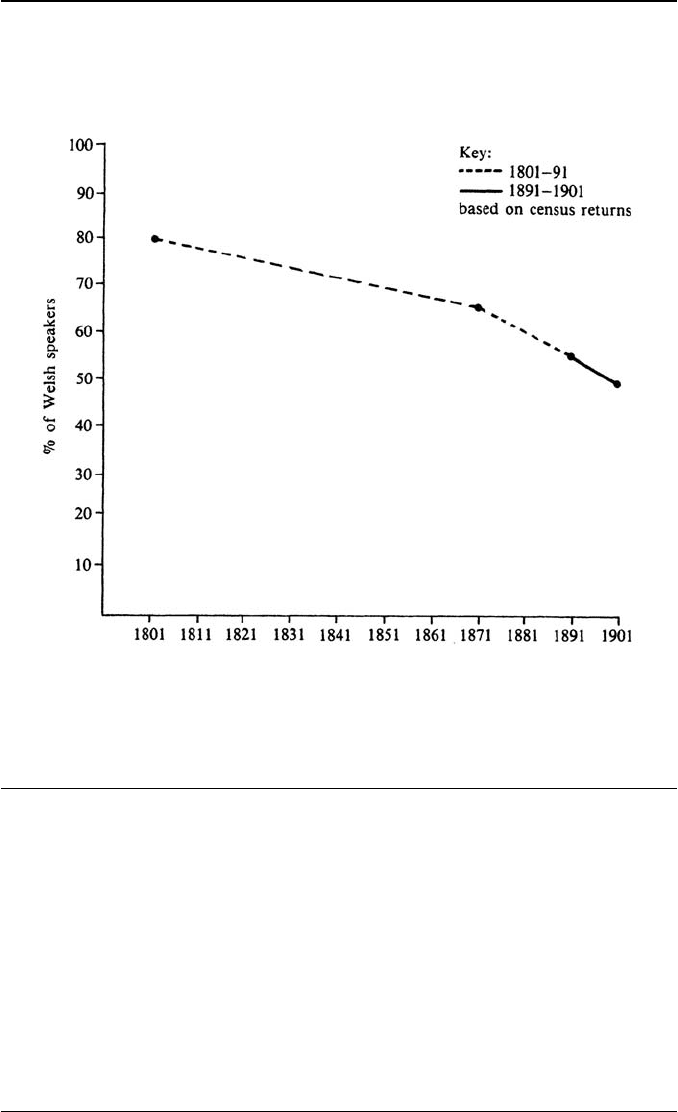

As shown in Figure 14.1 this reveals a slight decline (approximately 14 per cent) over a

period of seven decades. J. E. Southall (1895: 24) records 54.5 per cent as being Welsh

speaking with 29 per cent being monoglot Welsh speakers according to the census fi gures

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 657

for 1891. The decline during the two decades 1871–91 had been extremely sharp – (17 per

cent) almost double the rate for the preceding seventy years. According to the 1901 census

fi gures the Welsh- speaking percentage had dropped further to 49.9 per cent, but as Table

14.1 illustrates, the rate of decline was not uniform throughout Wales.

Table14.1 Percentage of Welsh speakers in the counties of Wales, 1891–1901. Source:

based on census data for 1891, 1901

1891 1901 Increase/decrease

Anglesey 95.5 91.7 –3.8

Cardigan 95.25 93.0 –2.25

Merioneth 94.25 93.7 –0.55

Caernarfon 89.5 89.6 +0.1

Carmarthen 89.5 90.4 +0.9

Flint 68.0 49.1 –18.9

Denbigh 65.5 61.9 –3.6

Montgomery 50.5 47.5 –3.0

Glamorgan 49.5 43.5 –6.0

Brecon 38.0 45.9 +7.9

Pembroke 32.0 34.4 +2.4

Monmouth 15.0 13.0 –2.0

Radnor 6.0 6.2 +0.2

Figure 14.1 The decline of Welsh speakers, 1801–1901. Sources: 1801 – Darlington

1894; 1871 – Ravenstein 1879; 1891 – Southall 1895; 1901–81 census returns

658 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

The decline was most apparent in the industrialized areas on the eastern side of the coun-

try – Glamorgan and Flint. The intriguing question is why there was such a sudden

decline at a time when nation- building processes were gaining ground and national insti-

tutions were being established. Thus the National Eisteddfod dates effectively from

1858. Teachers’ training colleges were established at Swansea in 1849 and at Bangor

in 1853. University College Aberystwyth was established in 1872, University College

Cardiff, in 1883 and University College of North Wales also in 1883. The Federal Univer-

sity of Wales came into being in 1893. But the telling, sad observation is that the Welsh

language was almost totally ignored in these educational establishments, apart from Uni-

versity College Cardiff where the fi rst Chair of Welsh was established and where teaching

was conducted through the medium of Welsh as opposed to the conventional practice of

teaching Welsh at university through the medium of English. Welsh disappeared from the

curriculum of Y Coleg Normal, Bangor, within fi ve years of its establishment. When Uni-

versity College Aberystwyth opened its doors in 1872, Welsh was not among the subjects

offered and that situation remained until 1875 simply because it was not regarded as a pri-

ority subject – it was not considered an academic fi eld of study. In fact the founders were

openly anti- Welsh. ‘The founders had said in a money raising circular that it was the dif-

fusion of English that was needed; Welsh they added could look after itself’ (Ellis 1972:

15). Welsh had a low socio- economic status. It was considered an inferior language which

could not cope with commercial, economic and academic matters. In the new world of

British imperialism, it was a fetter rather than an asset. Bilingualism, and ultimately Eng-

lish monolingualism, should be the goal of all who sought economic advancement. Welsh

was restrictive; English opened new doors. This emphasis on the dominance of English in

most status situations inevitably gave Welsh a low social- mobility profi le and this facili-

tated language erosion and shift. Gal (1979) cites a similar case in Austria after the First

World War. Social identity associated with German became desirable for social mobility

with a consequent gradual but defi nite shift from Hungarian. How people perceive their

language is extremely important because very often language status is seen as a manifes-

tation of the social status of its speakers.

According to John Rhys and D. Brynmor Jones (1900: 549), between 1801 and 1891

the total population of Wales trebled. Welsh speakers doubled in number but the increase

in monoglot English speakers was sevenfold, mainly because there was a large- scale

immigration into the industrial areas of monoglot English speakers from 1860 onwards.

The majority were not linguistically assimilated into the Welsh- speaking communities.

Bilingual and mixed language areas developed into transitional areas with a consequent

language shift. The English monoglots tended not to become bilingual, but bilingual-

ism among speakers of Welsh led to an intergenerational language switch to English

in these mixed language areas.

6

E. G. Lewis (1973) argues that industrialization, with

its associated migration of workers, was mainly responsible for the sharp decline in the

percentage of Welsh speakers during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. A heavy

infl ux of a monoglot English element into Glamorgan changed the demographic pat-

terns of the county and tipped the linguistic balance by making English the majority

language.

Before 1850 immigration into the industrial south- east had been from other areas in

Wales and so the population would have been almost entirely Welsh speaking. Between

1851 and 1901 the rate of increase in population in Glamorgan was six times the rate in

other areas. The population increased by 1,210,000, and approximately half of these were

immigrants – the majority coming from rural areas of the west of England. During the

period 1871–81, the rate of infl ow into Glamorgan was higher than into any other area

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 659

in Britain, and of this infl ux 57 per cent came from England. The result obviously was

a mixed language area. The intensity of Welsh speakers within communities was con-

siderably diluted, and this in turn led to language erosion. It is estimated that in 1850 the

proportion of Welsh speakers in the most anglicized areas of Glamorgan was 65 per cent,

and in the upper peripheries of the valleys it was as high as 98 per cent (E. G. Lewis 1973:

55). By 1891 this proportion had fallen to 49.5 per cent, although fi ve registration dis-

tricts showed returns in excess of 60 per cent. Immigration had affected the intensity of

Welsh speakers within communities and with a higher level of bilingualism among Welsh

speakers, everyday life outside the home and chapel became dominated by English. The

domains of the language were therefore considerably restricted, which made language

shift a normal process and language maintenance a conscious act of defying this trend

which characterized the majority.

Industrialization was the prime force with immigration as a contributory factor, but

at the root of erosion, facilitating language change, was the low status afforded to Welsh

since the middle of the century and the psychological effect which this inferiority syn-

drome had on Welsh speakers themselves.

7

On 10 March 1846 William Williams, MP

for Coventry, asked in the House of Commons for a Royal Commission to examine the

state of education in Wales. He argued that the socio- economic unrest of the period, as

manifested in the Rebecca Riots and the Chartist movement, arose out of ignorance of

the English language. This was a communication problem which could only be solved

by the masses learning English rather than by the masters and industrialists learning

Welsh!

If the Welsh had the same advantage for education as the Scots they would, instead

of appearing as a distinct people, in no respect differ from the English. Would it not

then be wisdom and sound policy to send the English schoolmaster amongst them.

The people of that country labour under a peculiar diffi culty from the existence of an

ancient language.

(quoted in Edwards 1987: 124)

The Report of the Royal Commission in 1847 (Part II: 66) was in a similar vein.

The Welsh language is a vast drawback to Wales and a manifold barrier to the moral

progress and commercial prosperity of the people. Because of their language the

mass of the Welsh people are inferior to the English in every branch of practical

knowledge and skill . . . Equally in his new or old home his language keeps him

under the hatches being one in which he can neither acquire nor communicate the

necessary information. It is the language of old fashioned agriculture, of theology

and of simple rustic life, while all the world about him is English . . . He is left to

live in an underworld of his own and the march of society goes completely over his

head!

It is ironic that protests to the Report referred to as the ‘Treachery of the Blue Books’ cen-

tred on the attack made upon the moral fi bre and development of the Welsh.

8

They did not

protest vehemently against the degrading and insulting references to their language. It

seems that the situation created by the Act of Union, whereby the social role of Welsh had

been curtailed and English made the offi cial public language, had left a mark on people’s

attitudes and perception. ‘The Treachery of the Blue Books’ went one step further in that

it constituted an open attack on the will of the people to support their language. Welsh was

660 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

equated with poverty, ignorance and low status. All useful knowledge and social stand-

ing could be acquired through the use of English. In 1866 The Times stated that ‘the Welsh

language is the curse of Wales’ (quoted in Edwards 1987: 130) and such statements were

certain to have a catastrophic effect in the fi eld of education.

When a system of elementary education for the children of Wales was developed the

Welsh language was totally ignored. It was taken for granted by the English promoters

and by the Welsh people themselves that education through the medium of Welsh would

be ineffective and useless. In 1864 J. B. R. Jones stated that Welsh might be of help in the

teaching of English, but it could not possibly be a fi eld of study itself: ‘to make a child

a Welsh scholar, and Welsh scholar only would be simply preposterous at this day’. The

Welsh language was an impediment: ‘in the way of education which is necessary for

the Welsh labourer who aspires to become an employer . . . generally speaking it does not

materially aid . . . in fi lling the empty cupboards and purses, and in satisfying the cravings

of the hungry children of even those who cling to its sympathies with such patriotic and

romantic ardour’ (quoted in Edwards 1987: 140). The Education Act of 1870 refl ected this

low esteem of Welsh by totally ignoring the language, and the whole purpose of education

in Wales was to make monoglot Welsh children bilingual and to promote literacy in Eng-

lish alone. Children were punished at school for speaking Welsh and they were actively

encouraged to carry tales to the teacher if one of them spoke Welsh. When a child was

caught speaking Welsh he had to wear a cord around his neck with the words ‘WELSH

NOT’. This was considered the ultimate disgrace. This sign would then be passed on to the

next child who was caught breaking the English- only rule. At the end of the school day the

child wearing the sign was severely punished.

As a result of the 1889 Education Act, intermediate schools were established in Wales

but Welsh as an academic subject in the school curriculum was limited to a small number

of schools where it was offered as an optional subject. In traditionally strong Welsh-

speaking areas, therefore, English was the normal medium of education, of administration

and of pupil–teacher interactions. As noted by Professor Jac L. Williams (1963: 52),

‘There was no national language policy and Welsh opinion at all social levels revealed

very little enthusiasm for extending the use of the language, beyond the home, the chapel

and the eisteddfod.’

During the 1880s there was a slight shift in opinion when the Society for the Utiliza-

tion of the Welsh Language in Education advocated a greater use of Welsh at elementary

level but mainly as a means of teaching English more effectively, a means of achieving a

higher level of bilingualism.

9

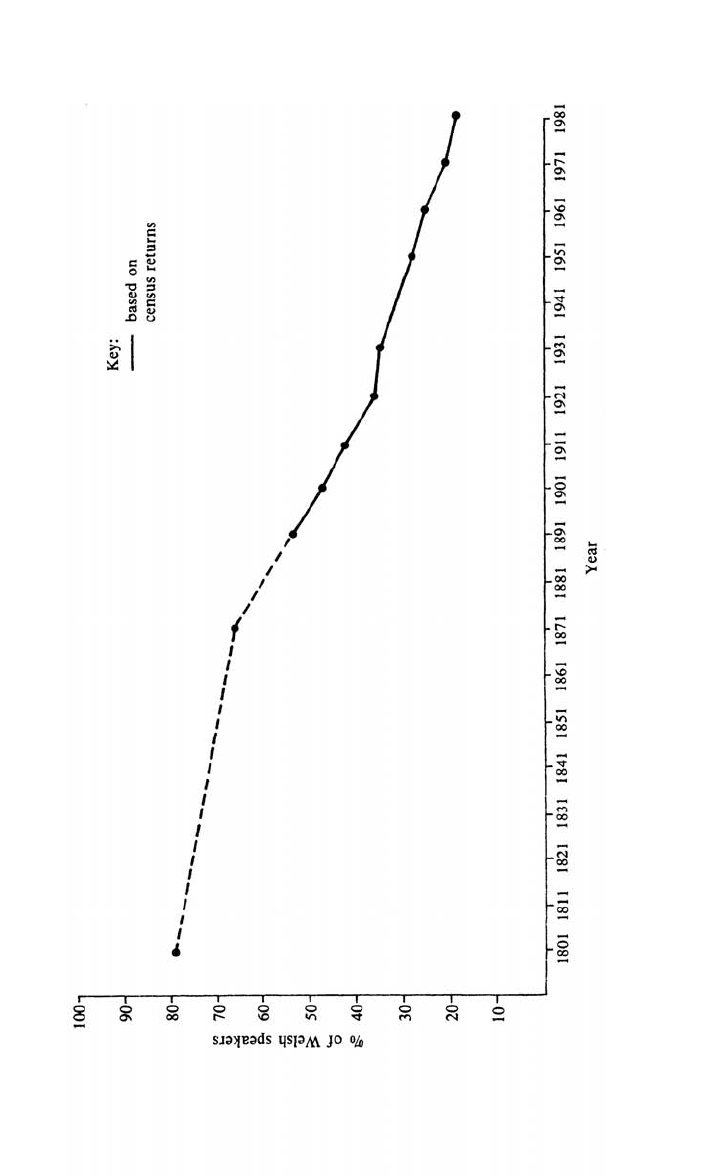

This certainly was achieved because by the turn of the cen-

tury 69.8 per cent of all Welsh speakers were bilingual. The proportion of monolingual

Welsh speakers fell drastically during the next eight decades. The 1981 census fi gures

reveal that only 4.2 per cent of all Welsh speakers were monolingual and in terms of the

whole population of Wales, the monolingual Welsh speakers constituted only 0.8 per cent.

In terms of actual numbers the Welsh monoglots had dwindled from the 280,900 of 1901

to a mere 21,283 in 1981 (see Figure 14.2).

Figure 14.2 The decline of Welsh speakers, 1801–1981. Sources: 1801 – Darlington 1894; 1871 – Ravenstein 1879; 1891 –

Southall 1895; 1901–81 census returns

662 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

Table 14.2 Percentage of Welsh speakers: monoglots/bilinguals

1901 1911 1921 1931 1951 1961 1971 1981

Monoglots 30.2 19.47 16.9 10.76 5.76 3.99 6.02 4.2

Bilinguals 69.8 80.53 83.1 89.24 94.24 96.01 93.98 95.9

Table 14.3 Percentage of population speaking Welsh or monoglot English

1901 1911 1921 1931 1951 1961 1971 1981

Welsh speakers

49.9 43.5 37.1 36.8 28.9 26.0 20.8 18.9

Monoglot

English

50.1 56.5 62.9 63.2 71.1 74.0 79.2 81.1

As Table 14.2 illustrates, by 1981 approximately 95.8 per cent of all Welsh speakers were

bilinguals. During the same period the total number of Welsh speakers had decreased

from 929,800 in 1901 to 503,549 in 1981. Table 14.3 shows the percentage of the popula-

tion able to speak Welsh in 1901–81.

Figure 14.2 shows that the rate of loss of Welsh was slow during the fi rst seven decades

of the nineteenth century. The rate for each of the next two decades was equal to the total

for the fi rst period. During the following seven decades the rate of loss slowed down but

was over three times the rate for the fi rst period. It is ironic that the percentage difference

between the stronger and the weaker language is the same in 1981 as in 1801 except that

there is a reversal in the roles of stronger/weaker at the two extremes of the time scale.

Such statistics are, of course, arresting and would seem to indicate that bilingualism in

Wales was a failure, in that it worked in one direction only. Welsh speakers acquired Eng-

lish, while the reverse infrequently happened.

10

It would seem that there is a link between

language erosion and shift and bilingualism, but obviously the same patterns of change

are not exhibited in the same intensities in all areas of Wales.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF WELSH SPEAKERS –

TWENTIETH CENTURY

Professor John Morris- Jones’s optimism concerning the Welsh language (Morris- Jones

1891) may appear misplaced when one considers that the 1891 census report indicated

that only 54 per cent of the population was then Welsh speaking. But one fact needs to

be borne in mind: the English monoglots were confi ned to certain areas, notably the

industrial south and north- east. Welsh remained the majority language in the largest pro-

portion of the geographical area of Wales (see Table 14.1, p. 657). Southall (1895: 25–6)

comments, ‘if we exclude the monoglot English in Monmouthshire and the Cardiff and

Swansea districts, the percentages would run thus: English 27.75, Welsh 72.25. These

percentages tally very nearly with the estimate which has been repeatedly expressed in

public, that seven out of ten Welsh people speak Welsh.’ Based on Anglican Church vis-

itation returns Pryce (1978) plotted the territorial erosion of Welsh, between 1750 and

1900. The map in Figure 14.3 shows that up to 1750 only a slender buffer zone along the

Welsh–English border had shifted to English.

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 663

By 1900 the boundary had shifted still further westward with the most apparent

changes seen in the south- east in Glamorgan. Certain changes were also taking place

beyond the main linguistic frontier, in that there appeared small pockets of English domi-

nance mainly in small towns and new resorts scattered along the North Wales coast. Over

most of the land area of Wales, however, the Welsh language dominated in that it was the

fi rst language of the communities with an intensity factor of 80 per cent or over.

In an area extending through Carmarthenshire into Cardigan, northwards into the

west and north of Montgomeryshire and thence to Meirioneth, Denbigh, Caernarfon and

Anglesey, over 80 per cent of the population was Welsh speaking in 1931 (Figure 14.4,

overleaf). One could travel from Holyhead through Wales to the southern coast and Welsh

Figure 14.3 Westward movement of English, 1750–1900. Source: after Carter 1989

664 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

could be used as the normal everyday medium of communication. But, however, during

the three decades the percentage of Welsh speakers decreased and inroads were made

into this Welsh- speaking heartland. Throughout the period the Welsh monolingual cat-

egory dropped sharply with the greatest erosion recorded prior to 1911. Between 1911

and 1921 the bilingual category dropped from 35 per cent to 30.8 per cent. C. H. Williams

(1980) is of the opinion that this happened because bilingual children of the previous

decade switched to become monolingual English adults. He drew attention to the vital

necessity of maintaining intergenerational family transmission of Welsh and advocated

a national programme to target the language choice of young parents- to- be.

11

This lan-

guage switching was undoubtedly a phenomenon which mainly characterized industrial

Figure 14.4 Areas with 80 per cent Welsh speakers in 1931 and 1951. Source:

D. T. Williams 1937

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 665

areas where there was already a strong monoglot English element in the communities. In

socio linguistic terms this was an expected development since the language of the majority

had prestige, economic value, educational and social connotations and had been actively

promoted for generations as the key to prosperity. The Welsh language had a specialized

use in certain domains, but social changes meant that the role of the chapel, the liter-

ary meeting, and the local eisteddfodau was being displaced by workingmen’s clubs and

by entertainment and leisure activities which were predominantly English medium. The

period 1931–51 saw a further sharp decline in the numbers of Welsh speakers. This was

accompanied by a further contraction of the Welsh- speaking heartland (see Figure 14.4).

The solid geographical area of 1900 (Figure 14.3) was not only shrinking along the east-

ern and southern periphery, but the linguistic infl uences of the small towns and tourist

resorts of 1901 had spread inland from the north Wales and Cardigan coast.

By 1961 the Welsh- speaking population had fallen to 659,022, comprising 26 per cent

of the total population of Wales. In 1931 the proportion stood at 36.8 per cent. There had

been a constant diminution of those able to speak Welsh, but this was more noticeable in

areas which had a density of under 50 per cent speaking Welsh in 1951. In geographical

terms there were only minor changes in the spread of English and in the erosion of Welsh

since 1931. Jones and Griffi ths (1963: 195) state, ‘The distribution has changed very little

except in detail since the 1931 data were made available . . . Comparison with the 1951

map shows that inroads of increasing anglicization have been small and along some sec-

tions only of the language divide.’ As is apparent from Figure 14.5 (overleaf) in 1961

one could see a sharp division between Welsh Wales and English Wales. Anglesey, Caer-

narfon, Meirionnydd, Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire, together with west Denbighshire,

west Montgomeryshire and north Pembrokeshire were predominantly Welsh speaking

(over 80 per cent). The main areas of the rest of the country were under 30 per cent Welsh

speaking. Jones and Griffi ths (1963: 195) concluded that ‘The distribution emphasizes

that there is a predominantly Welsh Wales, fairly sharply divided from a highly anglicized

area and yielding territory only reluctantly to the small peripheral advances of the latter.’

Such a description, however, would not be apt for the 1961–81 period. The decline in

territorial terms up to 1981 was dramatic. The solid territorial base of 1931 was, by 1981,

a highly fragmented one.

A comparison of the 1961 census fi gures with the 1971 fi gures shows how the domi-

nance and intensity of Welsh speakers had changed and the greatest decline was along the

periphery of the central core. Bowen and Carter (1974) proposed that suburbanization,

the growth of tourism and the popularity and development of some regions as retirement

areas had accelerated erosion along the north Wales and Cardigan coasts. C. H. Williams

(1981) cites urbanization as a prime factor in anglicization, suggesting that the Welsh/Eng-

lish divide was synonymous with rural/urban distinctions. Suburbanization from the 1960s

onwards further depleted the rural Welsh heartland.

12

Migration from rural areas to urban

areas meant that individuals and families lost the opportunity to use Welsh as the natural

medium of communication in everyday situations. Use of the language was considerably

restricted and a much wider spectrum of registers became English based. Without institu-

tional support for the language in such communities it had very little scope for succeeding

as a vital communicative medium. Added to this apparent failure of the language within the

urban environment was the gradual increase in the numbers of retired monoglot English

immigrants in the traditional Welsh- speaking areas, followed by the second- home buyers

who were often able to outbid locals for properties in rural Wales. They were later followed

by the ‘post- industrial’ trek of younger immigrants with young families who sought a new

life away from the bustle and strains of urban living.

13

Such immigrants are often unaware