Ball Martin, M?ller Nicole. The Celtic Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

586 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

Watson, I. (2003) Broadcasting in Irish. Minority Language, Radio, Television and Identity, Dublin:

Four Courts Press.

—— (1997) ‘A history of Irish language broadcasting: national ideology, commercial interest and

minority rights’, in Kelly, M. and O’Connor, B. (eds) Media Audiences in Ireland, Dublin: UCD

Press, pp. 212–30.

Williams, N. (2006) Caighdeán Nua don Ghaeilge? An Aimsir Óg, Páipéar Ócaideach 1. Baile Átha

Cliath: Coiscéim.

CHAPTER 13

SCOTTISH GAELIC TODAY

Social history and contemporary status

Kenneth MacKinnon

GAELIC IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Scotland’s linguistic history is complex. Its original inhabitants in early historical times

spoke a form of early Welsh – although what the northern Picts spoke is conjectural (Jack-

son 1955). The Gaelic language originally came to Scotland c.

AD 500 with the expansion

of the Northern Irish kingdom of Dál Riata into the western Highlands and Islands of

Scotland (Bannerman 1974). The expansion of this settlement, and the subsequent absorp-

tion of the Pictish kingdom in northern Scotland, the British kingdom of Strathclyde in

south- western Scotland, and part of Anglian Northumbria in the south- east, established a

largely Gaelic- speaking Scottish kingdom roughly conterminous with present- day Scot-

land by the eleventh century. Place- name evidence attests to this: names of Gaelic origin

are found throughout Scotland, and only in the Anglian south- east borders, and Norse

north- eastern Caithness and the Northern Isles, are they sparse (Nicolaisen 1976). Here

Norse settlement brought about the development of the Norn language, which lingered in

Shetland until the eighteenth century.

Celtic Christianity gained infl uence throughout this area from the coming of Columba

from Derry to Iona in 563, and this missionizing ‘Celtic’ Church fi rst brought literacy and

learning not only to the Gaelic Scots and their near neighbours but to much of England

also (Green 1911: 43–8). From the reign of Malcolm Canmore (1059–96), Gaelic lost its

pre- eminence fi rst at court; then among the aristocracy to Norman French infl uences; and

subsequently in the Lowlands, through the establishment of English- speaking burghs in

eastern and central Scotland, to English or Scots.

In the medieval period the British speech of Strathclyde was superseded fi rst by

Gaelic (Thomson 1968: 57), and subsequently by Scots, the West Germanic language

which developed from the Anglian speech of the Lothians. Language shift from Gaelic

to Scots proceeded across eastern Scotland and the western Lowlands, with Gaelic prob-

ably becoming extinct in south- western Scotland by the eighteenth century (Lorimer

1949–51).

By the seventeenth century Gaelic had retreated to the Highlands and Hebrides, which

still retained much of their political independence, Celtic culture and social structure. These

differences came to be seen as inimical to the interests of the Scottish and the subsequent

British state, and from the late fi fteenth century into the eighteenth a number of acts of

the Scottish and British parliaments aimed at promoting English- language education fi rst

among the aristocracy and subsequently among the general population; at outlawing the

588 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

native learned orders; and fi nally at disarming and breaking the clans and outlawing High-

land dress and music.

In the nineteenth century, contemporaneously with the notorious ‘Highland Clear-

ances’, which involved the enforced migration of the crofting population in many of the

Highland estates, a popular and successful voluntary Gaelic schools system came into

being. This was superseded after legislation in 1872 by a national English- medium school

system in which Gaelic had very little place. Some measure of security was given to the

crofting community by legislation in 1886. Despite the extension of the franchise and

the development of local government, recognition of Gaelic was initially very slow in

coming. Yet throughout the nineteenth century there had been vigorous calls for a place

for Gaelic in public life as well as in education. Withers (1988: 336) quotes a tract of 1828

seeking offi cial use of Gaelic in ‘the courts and other places of business’. Gaelic had a

central place in the religious life of the Highlands and in religious revivals. The language

was a political medium in the land agitation of the latter part of the nineteenth century, and

calls for its offi cial recognition were made in evidence to the Napier Commission inquiry

into the condition of the crofting community in 1883. A survey of Highland school boards

in 1876 revealed a ‘distinct majority in favour of including Gaelic in the curriculum’,

which met with some permissive response from the Scottish Education Board, but little

positive action by the Board or its inspectors (Smith 1983: 259–60).

From 1904 it was possible to take Gaelic as a ‘specifi c subject’, and the 1918 Edu-

cation Act provided for Gaelic to be taught ‘in Gaelic- speaking areas’, but these were

undefi ned and in practice very little was provided in terms of Gaelic education. However,

by the mid- twentieth century some instrumental acknowledgement of Gaelic had been

made by the Highland county education authorities, and from 1958 Gaelic began to be

used as an initial teaching medium in the early primary stages in Gaelic- speaking areas.

The language could be studied as an examination subject in parity with other languages at

the secondary stage. Since 1882 it had been possible to take Gaelic as part of a university

degree in Celtic. Some signifi cant developments in Gaelic education have occurred since

the mid- 1970s such as the bilingual education schemes in the Western Isles and Skye,

and the introduction of Gaelic as a second language at primary level. After its creation in

1975, the Western Isles authority, Comhairle nan Eilean, introduced a bilingual admin-

istrative policy, and bilingual schemes in primary education. However, in 1979 its nerve

failed and it did not extend this to the secondary stage. In other Scottish regions, such as

Highland and Strathclyde, bilingual primary education was making some headway in this

period, and from 1985 Gaelic- medium primary education was initated in two schools: at

Inverness and Glasgow. By 2008–9) these had increased to 60 schools with 2,206 pupils.

The neglect of Gaelic in the education system after 1872 resulted in the language sur-

viving as an oral rather than a literary medium for many of its speakers. The purpose of

school was to promote English literacy. Thus traditional Gaelic literacy was associated

with a religious culture which emphasized Bible reading, home worship and the singing

of the Metrical Psalms. Calvinism has promoted Gaelic literacy, and in the strongholds of

the Free Church and Free Presbyterian Church, where Protestantism, supportive educa-

tion policies and high incidence of Gaelic speakers have combined, Gaelic literacy can be

compared with English literacy levels, as in northern Skye, rural Lewis, Harris and North

Uist. Gaelic literacy is lower in Catholic South Uist and Barra, as the religious culture has

not emphasized the Gaelic scriptures as has Calvinism. This effect can also be shown as

between Gaelic speakers in mainland Catholic and Protestant areas (MacKinnon 1978:

65–7). In the 1981 census, 56.2 per cent of all Gaelic speakers had claimed to be able to

read Gaelic, and 41.6 per cent to write it. In the 2001 census, despite the contraction of the

SCOTTISH GAELIC TODAY 589

language group, these proportions had increased to 66.4 per cent and 53.0 per cent respec-

tively (Census 2001, Table UV12), indicating some success of Gaelic education policies.

However, the practice of writing Gaelic – even for personal letters – is very rarely under-

taken, and among older Gaelic speakers, and in areas where the language is not taught in

the schools, Gaelic speakers’ writing ability is weak.

Baker (1985: 22–40) has observed that in Wales higher levels of Welsh literacy asso-

ciate signifi cantly with language retention. There is some census evidence that this is also

true for Gaelic. In the author’s analysis of the 1981 census results, Gaelic reading and

writing levels correlated signifi cantly with intergenerational language maintenance in

Skye and Western Isles enumeration districts (MacKinnon: 1987a).

THE GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE GAELIC SPEECH

COMMUNITY

In 2001 speakers of Scottish Gaelic of all ages numbered 58,969. Speakers aged three

years and over totalled 58,652. Some 15,723 (or 26.81 per cent) resided in Na h- Eileanan

Siar, the Western Isles council area. Some 5,301 (or 9.04 per cent) resided in the Inner

Hebrides and Clyde islands. Some 11,956 (or 20.4 per cent) resided in the mainland High-

lands, and 25,672 (or 43.8 per cent) in the rest of Scotland or Lowland area. Thus almost

half of Scotland’s Gaelic speakers were resident outwith the traditional Highlands and

Islands area or Gaidhealtachd (Census 2001 Gaelic Report, Table 3). Since the end of

the nineteenth century the language group had contracted to some 23.05 per cent of its

former size, and migration had considerably changed the distribution of the language

group nationally. Numbers and percentages for corresponding areas in 1891 comprised

41,742 (16.4 per cent) resident in the Outer Hebrides; 33,851 (13.3 per cent) in the Inner

Hebrides and Buteshire; 121,970 (47.9 per cent) in the mainland Highlands; and 56,852

(22.4 per cent) in the rest of Scotland/Lowland area, respectively (Census Scotland 1891,

Gaelic Return, Table 1, pp. 2–18).

In 1891, 164,436 or 64.6 per cent of all Gaelic speakers lived in Gaelic- majority areas,

where Gaelic speakers numbered more than 50 per cent of the local population. These

areas comprised the Outer and Inner Hebrides in toto, the mainland Highlands (excepting

north- eastern Caithness, the eastern fringes and larger towns), and much of Buteshire. A

more signifi cant proportion is the 70 per cent (or more precisely 70.7 per cent) incidence

level which characterizes areas where there is a greater than 50 per cent likelihood of local

Gaelic speakers meeting on an everyday basis and using their language. These areas are

thus Gaelic- predominant or Gaelic majority- usage areas. In 1891, 123,848 (48.7 per cent)

of all Gaelic speakers lived in such areas, which then comprised the Outer Hebrides, Isle

of Skye and Inner Hebrides, northwestern, western and central Highlands.

The corresponding situation in 2001 is very different. Gaelic- majority areas comprised

the northern tip of Skye and 11 of the Western Isles’ 16 census wards (home to 11,777

Gaelic speakers: 20.1 per cent of the national total), and Gaelic- predominant or majority-

usage areas comprised only fi ve of them (with 4,774 Gaelic speakers: 8.1 per cent of the

national total).

Up until the end of the twentieth century, local native Gaelic speakers, chiefl y of

the older generation, could still be commonly found in all the western coastal areas of

the Highlands. There were also still some vestiges of native Gaelic in most parts of the

mainland Highlands, even in Highland Perthshire. However, such has been the rate of lan-

guage shift in Gaelic communities that it is now highly questionable whether such a thing

590 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

as a Gaelic- speaking community is likely to last much longer, and whether local native

speakers will be encountered over much of the remaining traditional Gaelic area, notwith-

standing the considerable recent improvements in institutional support for the language

discussed below.

The near majority of Gaelic speakers who were resident outwith the traditional

Highlands and Islands area in 2001 cannot be said to constitute a true Gaelic- speaking

community. They may form networks or share some aspects of social life through the lan-

guage, but their working lives and most other aspects of living will be conducted through

English. In terms of airtime the Gaelic media are a tiny proportion of what is available,

and Gaelic- medium education is far from being available to all who want it. However,

the Greater Glasgow area was home to about 10,000 Gaelic speakers in 2001 (with 9,965

Gaelic speakers in Glasgow and its contiguous council areas.) This provides a local con-

centration of Gaelic speakers which makes Gaelic provisions a great deal more feasible

and economic. In 2005 Glasgow initiated an entirely Gaelic- medium all- through school

(followed two years later by Inverness), and there are initiatives to create Gaelic social

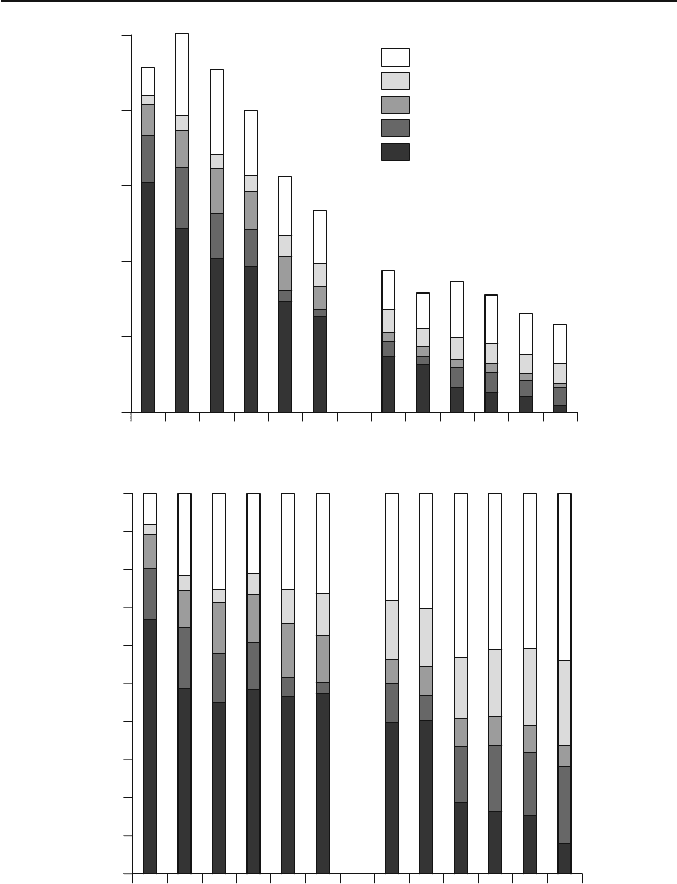

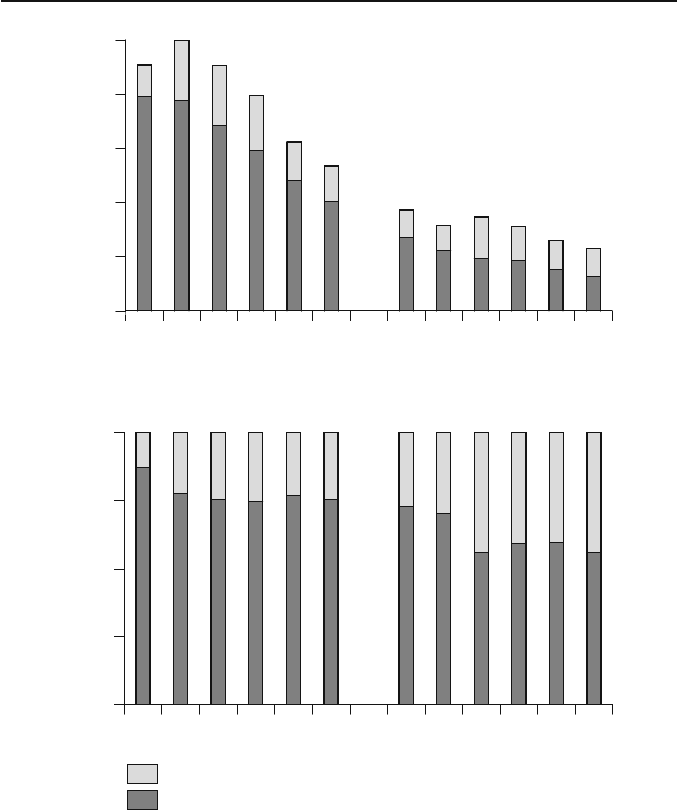

centres in both cities, and also in Edinburgh. Figure 13.1 (opposite) illustrates the chang-

ing proportion of Gaelic speakers between Highland and Lowland areas since 1881.

Figure 13.2 (p. 592) similarly illustrates the changing proportion of Gaelic speakers in

local areas of over 70 per cent, 50–69 per cent, 25–49 per cent, national average to 25 per

cent, and below the national average incidence.

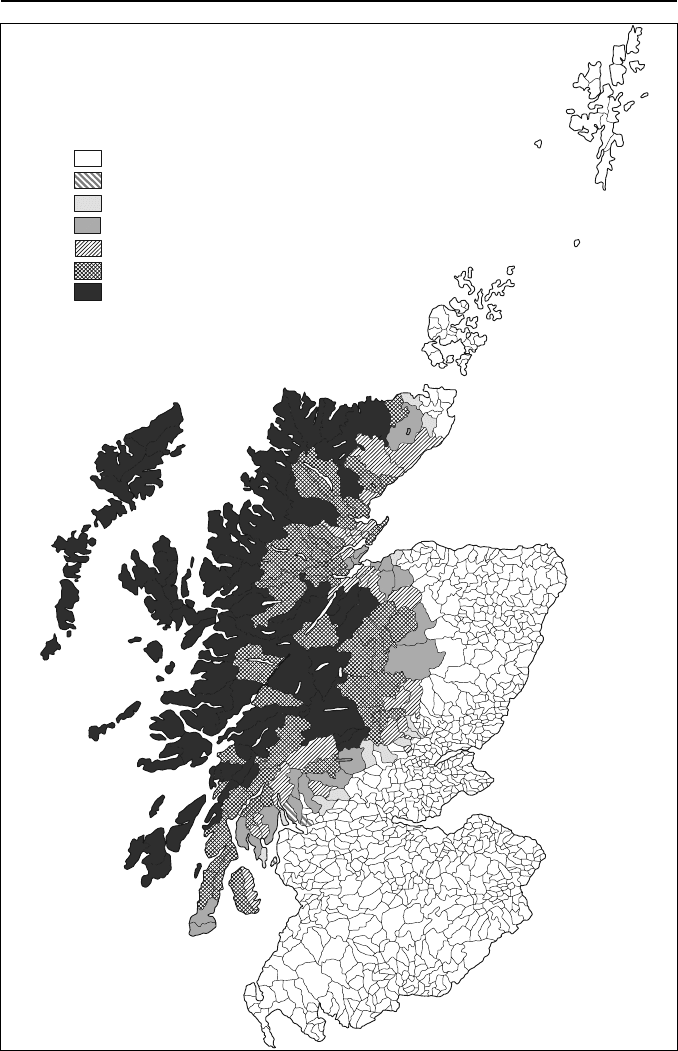

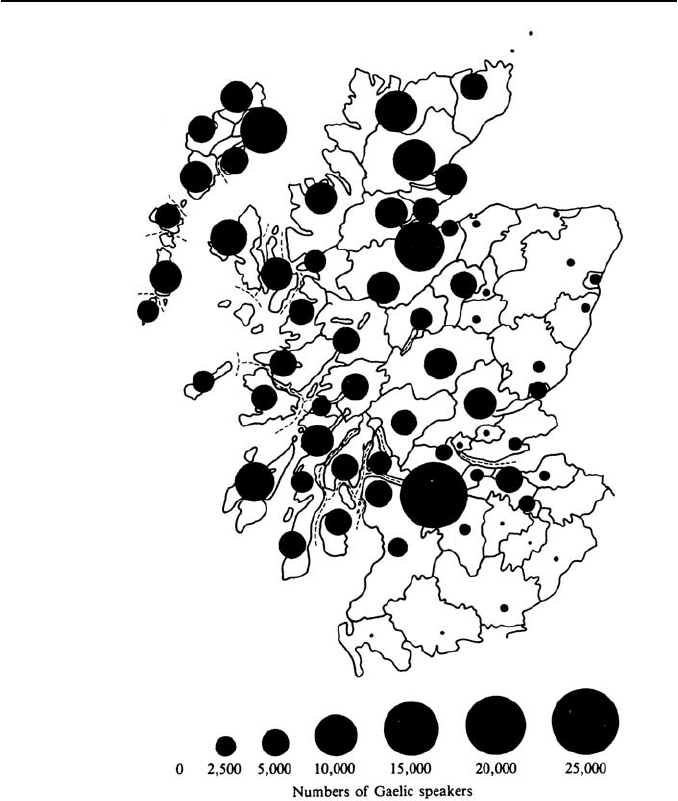

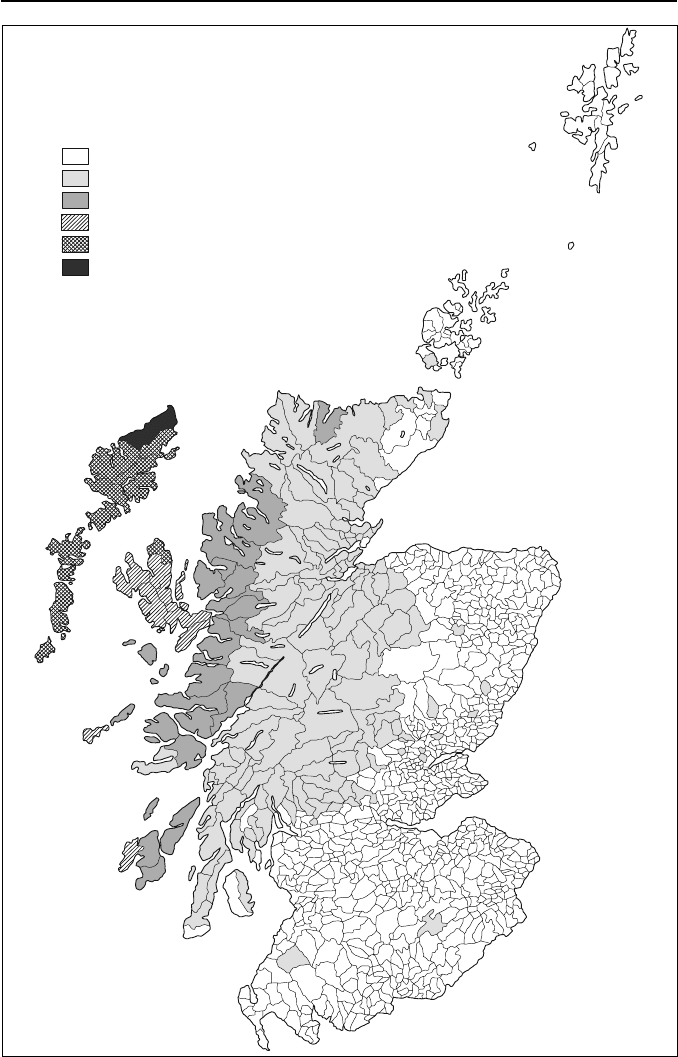

See also the maps in Figures 13.3, 13.4, 13.5 and 13.6 (pp. 593–6), which illustrate the

changing distribution of Gaelic speakers nationally.

Almost all parts of the traditional Gaidhealtachd still had a proportion of Gaelic speak-

ers greater than the national average in 2001. But it can no longer be said, as some still

do who should know better, that Scotland’s Gaelic speakers are to be found mainly in

the Hebrides and north- west coastal fringes. Today, the majority are in fact elsewhere in

Scotland, resident in areas which could not be described in any sense as Gaelic in either

present- day or recent historic character.

The problems which result from this distribution pattern of Scotland’s Gaelic speakers

mean that historically contacts within the Gaelic speech community have been particu-

larly diffi cult. The Highland mainland is mountainous and deeply indented by the sea.

Thus the small Gaelic populations of the western glens and peninsulas have been very

much isolated from one another. The islands are today typically connected by modern

lines of communication, not so much with one another as through ferry ports on the

west coast with road and rail links to the Lowland cities. In the past (prior to the 1975

local government reforms) Highland administrative areas had typically encompassed

both thoroughly Gaelic island and west- coast areas with the more populous and angli-

cized east- coast areas – as in the former Highland counties. In these and other ways, the

Gaelic areas have in the past been further divided from one another, and mutual contacts

between them have been reduced. The roles of the present- day broadcasting and educa-

tion services, and the policies of local administration are thus of particular importance in

overcoming these diffi culties. Because almost half of all Gaelic speakers are now located

within an urban, Lowland milieu, communications and educational policies are crucial to

the survival of the language nationally.

SCOTTISH GAELIC TODAY 591

Below national rate

National rate–24.9%

25–49.9%

50–69.9%

70%+

250,000

200,000

150,000

100,000

50,000

0

1881

1891

1901

1911

1921

1931

1941

1951

1961

1971

1981

1991

2001

1881

1891

1901

1911

1921

1931

1941

1951

1961

1971

1981

1991

2001

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Figure 13.1 Gaelic speakers by area of incidence 1881–2001 (a) numerical,

(b) percentages

(a)

(b)

592 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

1881

1891

1901

1911

1921

1931

1941

1951

1961

1971

1981

1991

2001

250,000

200,000

150,000

100,000

50,000

0

Gaelic speakers in Lowlands/rest of Scotland

Gaelic speakers in Highland and Islands areas

1881

1891

1901

1911

1921

1931

1941

1951

1961

1971

1981

1991

2001

100%

75%

50%

25%

0%

Gaelic speakers in Lowlands/rest of Scotland

Gaelic speakers in Highland and Islands areas

Figure 13.2 Gaelic speakers in Highland and Lowland areas 1881–2001 (a) numerical,

(b) percentages. Source: GROS 1931 census, Table 54; 1961 Gaelic Report, Table 3;

1971 Gaelic Report, Table A; 1981 census LBS, p. 9, Table 40; 2001 Gaelic Report,

Tables 1 and 3

(b)

(a)

SCOTTISH GAELIC TODAY 593

Percentage ranges:

Not shown on this map

Less than 6.32

6.32 to less than 10

10 to less than 25

25 to less than 50

50 to less than 70.711

70.711 or more

Figure 13.3 1891 census: persons aged 3 and over able to speak Gaelic, as a percentage

of total population, by civil parish. Source: General Register Offi ce (Scotland) 2008

594 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

Figure 13.4 Size and location of Gaelic populations: 1891 census Scotland

SCOTTISH GAELIC TODAY 595

Percentage ranges:

Less than 1.197

1.197 to less than 10

10 to less than 25

25 to less than 50

50 to less than 70.711

70.711 or more

Figure 13.5 Map 2001 census – parishes. Source: General Register Offi ce (Scotland) 2008