Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

234 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

orthodox, thinkers: for example, William of Champeaux (d. 1121) and John Wy-

cliffe (d. 1384) for the realists, and William of Ockham (d. 1348) and Jean Gerson

(d. 1429) for the nominalists.

St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) was an important transitional figure

from the Neo-Platonic and Augustinian model of the first half of medieval intel-

lectual life to the Aristotelian model of the second half. Anselm was a realist who

believed firmly in the power of reason to illuminate, though not to prove or au-

thenticate, faith. “I believe in order that I might know” summed up his approach.

Nevertheless, he was identified with the rationalist movement, and described the

role of reason in explaining and supporting faith in these terms:

I have been asked countless times, by mouth and by letter, to put down in

writing the proofs of any particular teaching of our faith, as I have grown

accustomed to do for those inquiring into it. I am told that these proofs give

pleasure and reassurance. Those who ask this of me do not necessarily try to

come to faith via reason; rather they live in the hope of being uplifted by

learning that the things they believe by faith and instinct are true.

Anselm’s most renowned contribution to western thought was the so-called on-

tological proof of God’s existence. It is really quite clever:

1. By God we mean the greatest of all possible beings, the one being that it is

impossible to conceive of anything else being greater than.

2. To exist in our minds alone, and not in reality, is a self-contradiction of the

very definition of God.

3. Therefore such a being, since we can conceive of it, must exist in reality

and not merely in our minds, for existing in reality is greater than existing

only in our minds.

Nevertheless, for Anselm faith remained a basic instinct and an emotional com-

mitment rather than an intellectual conviction. One cannot think one’s way to God;

but, beginning with faith in God, one can then think out a very great number of

life’s questions. Anselm was a beautifully subtle and moving writer.

By the time of his death, the cathedral schools were clearly on the rise. Anselm

himself had begun his career as a monk and finished it as a bishop, unintentionally

paralleling the seismic ground-shift taking place within the Church. The teachers

at these cathedral schools were mostly itinerant, traveling from place to place and

offering lectures and tutorials for cash; as their circuits spread, so did their repu-

tations. They traveled in search of money, renown, libraries, patrons, and, since

many of their new ideas were deeply upsetting to established orthodoxies, per-

sonal protection. The greatest of these wandering scholars was Peter Abelard

(1079–1142). The son of a Breton nobleman, Abelard showed his intellectual prom-

ise early in life and even before he finished his elementary studies was already

challenging his teachers. (In the often raucous atmosphere of the cathedral schools,

students could challenge their teachers to public debates on any given question.

Abelard did so and defeated his teacher William of Champeaux, who tried to

defend his extreme realist position. William’s teaching career never fully recovered

from the humiliation, while Abelard’s was launched.)

1

Abelard was the most bril-

1. A similar episode occurred in 1113 when Abelard attended a series of lectures delivered in a local

synagogue by the theologian Anselm of Laon—until they acquired facilities of their own, the early

schools sometimes rented space in established synagogues—that left him unimpressed. Anselm, the

leading theologian of his time, was lecturing on the Book of Kings but, complained Abelard, “while he

may have kindled a fire, he filled the room with far more smoke than light.” He challenged Anselm on

the spot. Abelard was given the opportunity to have one week to prepare a lecture on an obscure passage

from Ezechiel. Instead, Abelard lectured on the passage the very next morning, and did so with such

brilliance that he was driven out of town by the students loyal to Anselm. Abelard moved on to Paris.

THE RENAISSANCES OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY 235

liant member of his generation—and he knew it. His first book was his most

audacious and important. Entitled Sic et Non (“Yes and No”), it assembled texts

from the Bible, the Church Fathers, papal letters, and conciliar decrees that con-

tradicted one another on such fundamental questions as “Is God omnipotent, or

not?” and “Did God create evil, or not?” Abelard’s point was that the Church

could not rely solely on the authority of tradition to resolve such basic questions

of faith since the tradition itself was imperfect; instead, he argued, a rigorously

logical and scholarly approach was needed. “Diligent and constant questioning is

the fundamental key to all wisdom,” he wrote in the book’s majestic preface; “by

doubting we come to inquiry, and by inquiring we come to the truth.” Having

shown the need for a rational reconstruction of Christian thought, Abelard then

devoted himself to the task with fervor, teaching to large crowds in Paris and

writing a stream of philosophical and exegetical works. Crowds flocked to his

lectures, with some students traveling hundreds of miles to hear him: “The dan-

gers of travel meant absolutely nothing to them,” wrote one commentator; “they

all came in the firm belief that there was nothing he could not teach them.” If we

can take Abelard at his word, some of these students were so aflame with enthu-

siasm after his lectures that they occasionally lifted him onto their shoulders and

carried him home while chanting his name through the streets of Paris.

But that is not all he devoted himself to. As he later described in his autobi-

ography The History of My Misfortunes:

At that time there was in Paris a certain young girl named He´loı¨se. She was

the niece of a canon named Fulbert who, since he loved her dearly, was eager

to do all he could to help her progress in knowledge of letters. She was hardly

among the least of women in her physical beauty and was among the greatest

in the abundance of her learning.

Abelard agreed to tutor He´loı¨se, found her sexually irresistible, and soon seduced

her. But what began as a sexual conquest turned into genuine love. When she

became pregnant he offered to marry her, but she refused since marriage would

effectively end his career as a scholar (since all scholars were regarded as clerics,

whether or not they took holy orders). In a cruel blow, uncle Fulbert learned of

He´loı¨se’s pregnancy and hired a group of thugs who attacked Abelard one night

as he lay asleep and castrated him. The humiliation of his wound, which quickly

became known throughout Europe, led Abelard to renounce the world and enter

a monastery. At Abelard’s urging, He´loı¨se became a nun. They continued to cor-

respond throughout the rest of their lives—their letters survive and have been

frequently translated—but they seldom met face to face. Their baby was given to

Abelard’s sister.

Castration did not end Abelard’s “misfortunes,” however. His books kept get-

ting him into trouble. He was the sort of person who enjoyed flirting with heter-

odox ideas and tweaking the noses of accepted authorities, and his writings came

under attack from conservative quarters. His chief nemesis was St. Bernard of

Clairvaux, who pursued Abelard with considerable zeal. It was Abelard’s whole

approach, rather than any particular set of his ideas, that infuriated Bernard. To

Bernard, the rationalization of faith was tantamount to the trivialization of it. God

cannot be bound by the laws of syllogism, he insisted, and to suggest otherwise

is to commit a heinous crime of pride. Worst of all, to Bernard, Abelard was urging

young students to hold the basic tenets of faith up to questioning. “The faith of

the common people is being held up to scorn; the secrets of God Himself are torn

open; the most sacred matters are discussed with reckless abandon...[Abelard]

approaches the dark cloud that surrounds God not as Moses did—that is, alone—

236 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

but surrounded by a whole crowd of his disciples!” Abelard was certainly the

better scholar, Bernard perhaps the better man. But they spoke fundamentally

different languages, and their conflict illustrates the tensions existing in Latin

Christendom as a result of the new learning. In the end, several of Abelard’s books

were condemned at councils headed by Bernard; Abelard died at Cluny while en

route to Rome to appeal his case to the pope. Abelard and Bernard made peace

with each other before Abelard’s death, but it is important to emphasize that at

stake in the dispute between them was more than a clash of personalities and

egos. What truly separated them was an irreconcilable chasm—so it seemed in the

twelfth century—between the truths that are attained by logic and those that are

received by the revealed authority of the Church and its traditions. As Lanfranc

of Bec, the archbishop of Canterbury in the late eleventh century, put it: “Any

time a disputed topic can be best explained by means of the new [i.e., Aristotelian]

logic I always cover up the logical method as much as I can with the traditional

formulas of faith because I don’t want to appear to place more trust in the new

method than I place in the truth and authority of the Holy Fathers.”

The campaign to introduce Aristotelian logic in theological questions contin-

ued, however. Abelard’s pupil Peter Lombard (1100–1160) carried on his master’s

work and wrote the Four Books of Sentences, which became the standard textbook

for the study of theology for the rest of the Middle Ages. Few medievalists now-

adays bother to read the Sentences, but from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries

they were the core text of theological study at virtually every major university in

Europe; hundreds of scholars and would-be scholars wrote commentaries on them.

The book’s influence is most clearly shown in the establishment of the Church’s

final doctrine on the sacraments, a doctrine that rose directly from the commen-

taries on Lombard’s book. Until this time there had never been universal agree-

ment on the number of sacraments, or on which priestly acts were sacramental.

2

Lombard and the theologians who learned from him argued that there were seven

distinct acts established either by Christ himself, the Church, or tradition, that held

sacramental force: baptism, confession, confirmation, last rites, the Mass, marriage,

and ordination. All these rites, with the exception of marriage, had played a part

in priestly life down through the centuries, but not all had always carried sacra-

mental authority.

3

The influence of the Sentences reached its highpoint when the

Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 formally recognized the seven sacraments of of-

ficial Church doctrine.

Perhaps the greatest commentator on Aristotle in the twelfth century was the

Spanish Muslim writer ’Ibn Rushd (1126–1198), who is known in the west as Aver-

roe¨s. Aristotle challenged and worried the Muslim world as much as the Christian,

and perhaps more so, for Islam was based on the idea of the unique, absolute,

and perfect revelation of God to the Prophet Muhammad; nothing more than the

Qur’an was needed, and even to suggest otherwise smacked of heresy. Islam had

brilliantly adapted to most of classical culture once it had made contact with it,

but its embrace of classical philosophy had always been wary. Medieval Islam

2. A sacrament, you will recall, is a priestly rite by which divine grace is bestowed upon the faithful;

this grace—and hence the rites that confer it—is essential to salvation. Baptism, for example, is a sac-

rament whereas a simple priestly blessing, while a rather nice thing, is not.

3. Marriage entered the sacramental canon in order to resolve a contradiction in Christian life. Lom-

bard’s commentators, following his lead, pointed out that the Church had long preached the superiority

of lifelong celibacy as the Christian ideal, but if everyone was celibate the faith would obviously die

out. The only rational solution was for the Church to legitimate a certain type of sexual activity (married

intercourse) as a positive spiritual act—the procreation of more Christian souls.

THE RENAISSANCES OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY 237

produced several philosophers of genuine brilliance, but these figures had been

marginalized, suspicious characters in their own lifetimes, like ’al-Kindi (d. 866),

’al-Farabi (d.950), and ’Ibn Sina (Avicenna, d. 1037). They are renowned as brilliant

scholars today but in the Middle Ages they were pariahs. ’Ibn Rushd was perhaps

the least controversial of them, but he got into trouble nonetheless. He was also a

world-class intellectual snob. He believed that Greek philosophy, and specifically

Aristotelian logic, could harmonize with and elucidate the great teachings of the

Islamic faith, “for truth does not contradict truth, but stands in accord with it and

bears witness to it.” But what should one do when logic appears to contradict

Qur’anic assertion? ’Ibn Rushd cautiously suggested that certain verses of the

Qur’an could not be read literally but needed to be interpreted metaphorically.

But since not all humans are capable of making such fine distinctions, ’Ibu Rushd

insisted that philosophical learning had to be kept under wraps, made available

only to those individuals who were capable of appreciating the subtleties of higher

thought. Philosophy was for the elite only.

Anyone who is not a scholar needs to take these [Qur’anic] passages in the

literal meaning; a metaphorical interpretation of them is, for such a person, a

waste of effort since it leads to a failure of faith....Metaphorical interpreta-

tions ought to be laid out only in scholarly books, because if they are laid out

only in scholarly books they will be read only by scholarly men.

But while ’Ibn Rushd’s elitism may seem distasteful, his understanding of Aristotle

was sublime. In a long series of books, he brought to light many aspects of the

old philosopher’s teaching. His influence within the Muslim world remained min-

imal, but in the Latin Christian world his commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics

had a dramatic impact. ’Ibn Rushd is in fact the only figure in all of Islamic history

to have spawned a Christian heresy. A group of theologians in Paris in the thir-

teenth century, most notably Siger of Brabant (d. 1284) and Boethius of Dacia (d.

1277), became so enamored of his work that they stumbled into a heterodox po-

sition known as Latin Averroism. They adopted his conviction that philosophy was

an end in itself, regardless of its theological consequences; and they further en-

dorsed his ideas about the “agent intellect” (a kind of collective consciousness that

every individual human participates in) and the eternity of matter (the doctrine

that all matter experiences transitions but remains eternal, without beginning or

end). Such teachings contradicted fundamental tenets within both Islam and

Christianity.

Reconciling reason and faith is difficult—and perhaps not even necessary. Af-

ter all, faith is by definition an irrational act; it means believing something despite

the fact that rational arguments cannot be made on its behalf. But in the highly

charged and confident atmosphere of the twelfth century, Latin Christians re-

mained convinced that it was possible, in the aftermath of Europe’s great reform,

to explain the world, to understand man, and to prove God. The results of their

efforts are thrilling to behold.

L

AW AND

C

ANON

L

AW

The revival of law was the second great achievement of the twelfth-century re-

naissance. This is hardly surprising: The lawlessness of the tenth and eleventh

centuries spawned as great an interest in legal reform as in ecclesiastical reform.

Feudalism and manorialism, as they developed, addressed some of these concerns

but in reality they raised as many problems as they solved. Old customary codes

238 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

no longer fit the ways of twelfth-century life, especially when they confronted the

problem of multiple customs. How could the Capetians, for example, built a uni-

fied, stable kingdom of France if “France” consisted of hundreds of individually

governed districts each with its own system of laws? In point of fact, nearly every

fief in feudal Europe had its own set of customs, although there were naturally

many similarities between them. Moreover, ancient western tradition had main-

tained a principle known as the personality of the law, which held that every person

was entitled to live under the laws or customs of his or her ethnic group. A free

Gascon scholar, in other words, still lived according to Gascon legal traditions even

if he or she lived in Burgundy; Milanese merchants residing in Marseilles were

judged by the customs of Milan; the Jews of London lived according to Jewish

law and answered to Jewish officials. One generally carried one’s law with one

(provided of course that you were a freeman). The growing medieval passion for

rationalized order demanded something different than the personality of the law.

But there was a problem. Until the twelfth century most people in Latin Europe

had a different conception of law than we do. Law to them was not a body of

regulations and privileges to be created, modified, or repealed as the jurisdictional

authorities deemed fit. Law was by definition permanent and unchanging; if a

way of doing things could be altered at will, it was not law. In other words, the

twelfth century thought of law in general the way that we think of the laws of

nature or laws of physics, sets of permanently fixed rules to which we must conform

our lives—not vice versa.

Two elements brought on change. Feudalism contributed the idea of territorial

rulership, the notion that a governing authority has jurisdiction over an area, not

only over a group of individuals. The early medieval kings had people-based, not

land-based, power. Thus Clovis was rex Francorum (“King of the Franks”) not rex

Franciae (“King of France”); Alfred the Great was rex Anglorum (“King of the An-

gles”) not rex Angliae (“King of England”). In theory, Alfred would still have been

“King of the Angles” even if they had all moved to Iceland. But with the rise of

feudalism and manorialism, the idea of direct jurisdiction over land gradually

developed. Feudal titles reflected this change. The man who granted independence

to the monastery of Cluny in 911 was William dux Aquitaniae (“Duke of Aqui-

taine”). The victor at the battle of Lechfeld in 955 was Otto dux Saxoniae (“Duke

of Saxony”). The man who conquered England in 1066 was William dux Norman-

niae (“Duke of Normandy”). The emphasis on territory instead of the ethnicity of

the territory’s inhabitants slowly undermined the doctrine of the personality of

the law. But the process was slow, given the conservatism of agrarian societies.

The second factor had a quicker influence. As mentioned earlier, the rediscov-

ery of the Corpus iuris civilis in the late eleventh century sparked immediate in-

terest among legal scholars. Discovered at a library in Pisa, the manuscript of the

Corpus made its way to Florence when a Florentine army, after an attack on Pisa,

carried it off as war booty. From there knowledge of it spread across northern

Italy. By 1100 a legal scholar named Irnerius lectured at the school in Bologna on

the complete text. Most significantly, Irnerius taught Roman law as a system,an

organic whole, not merely as a compilation of various bits of legislation, which is

how scraps of Roman laws had been known and passed on in earlier centuries.

By glossing the text of the Corpus—explaining obscure words, relating various

parts of the text to one another, and showing how the system evolved over time—

Irnerius emphasized that Roman law had an organic and inextricable relationship

to the society that spawned it and that it, in turn, regulated. Law as represented

by the Corpus, in short, is a constantly evolving social creation, not a static body

of immutable customs. The fundamental principles on which law is based, such

THE RENAISSANCES OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY 239

as an individual’s right to private property, Irnerius and his successors argued, do

not change, but as social systems and practice develop over time, it is necessary

for the specific legislation that implements those principles to develop as well.

Students interested in law flocked to Bologna, which quickly became the premier

site for legal study and training for the rest of the Middle Ages.

The impact of the Corpus was pervasive. For the urban south it provided an

immediate blueprint for administering society, even though obviously many of the

specific laws that were contained in the Corpus had to be jettisoned as no longer

appropriate. As one moved northward into feudal Europe, the direct incorporation

of the Roman law decreased, but even there the rulers made explicit attempts to

introduce the system into the emerging urban areas of those realms. Municipal

charters from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in England, France, and Ger-

many were clearly an amalgamation of Roman principles and specific local needs,

as shown by the language of King John of England’s (1199–1216) charter creating

the borough or city of Ipswich in the year 1200:

We grant and by this present charter confirm that we grant to the townsfolk

of Ipswich the borough of Ipswich with all its appurtenances, liberties, and

customs....Wealso grant them immunity from the customs in force through-

out our realm and throughout our seaports...and immunity from criminal

and civil jurisdiction outside the borough of Ipswich, on any issue except

those in relation to foreign tenures....Weestablish that in regard to all lands,

holdings, and possessions within the said borough of Ipswich justice shall be

administered to them according to the laws of Ipswich....We also forbid

anyone in our whole realm to exact [taxes] from the men of Ipswich, on pen-

alty of £10 to the royal [treasury]. We altogether wish and command that the

townsfolk of Ipswich shall have and retain the aforesaid liberties and customs

securely and peaceably....[Towards this end] we direct and command that

our said townspeople [of Ipswich]...shall elect two or more law-abiding and

circumspect men of their town...whoshall faithfully and honorably hold the

administrative office of that town, and that as long they conduct themselves

honorably in that office they shall not be removed, unless the common people

of that town so desire.

But the impact of the Corpus shows as well in the systematization of laws

throughout Europe. North and south, the states of Latin Europe began to codify

and standardize their legal codes along the lines of the Corpus. One or two ex-

amples will suffice. A jurist in the court of England’s king Henry II—tradition

attributes it (falsely) to his chief justiciar Ranulf Glanville—complied the first ma-

jor treatise On the Laws and Customs of England in 1188–1189 and proudly compared

England’s legal tradition with Rome’s. Henry Bracton’s even more comprehensive

treatise from around 1260 incorporated further elements from the Corpus and is

most famous for its hairsplitting attempt to integrate the old Roman maxim Quod

principi placuit legis habet vigorem (“What is pleasing to the prince has the force of

law”) with the Anglo-Saxon custom of the king being altogether under the au-

thority of the law:

Whatever is properly described, defined, and approved by the advice and

consent of the magnates and the common agreement of the realm has the

force of law, so long as the authority of the prince or king is first taken into

account.

Citations from the Corpus dot the municipal code (called the Usatges) of Barcelona

from the mid-twelfth century, while in 1268 King Alfonso X of Castile published

his monumental work called the Siete Partidas (“Book in Seven Parts”) that offered

240 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

a minutely detailed blueprint for administering a highly feudalized realm along

Roman legal principles. This plan required efficient central administrations, and

the emergence of the very idea of the State can be traced to the expansion of

Roman law. Such ideas were also put forth by France’s Philip Augustus and Ger-

many’s Frederick Barbarossa in their attempts to consolidate authority over their

often truculent barons. In the twelfth century, in other words, the originally private

and personal authority of feudal privileges bound by vow and tradition trans-

muted into a modern notion of government as a public authority endowed with

the power to legislate, create, annul, and adapt law as it saw fit.

The Church got into the act as well, since the reform of ecclesiastical law

(known as canon law) was a vital component of the overall reform movement. For

the Church’s inner governance, the bulk of the content of the Corpus was naturally

of little direct value, but its structural model it proved highly valuable. As early

as the late eleventh century, canonists were busily at work sifting through conciliar

decrees, papal proclamations, the writings of the patristic Fathers, and episcopal

letters, organizing them by topic, trying to resolve contradictory items, omitting

what had become outdated. One of the earliest of these sources was the reformer

Ivo of Chartres who in the 1090s produced two important compilations, to one of

which, called the Panormia, he added a preface that is Latin Christendom’s first

treatise on jurisprudence since ancient times.

4

Ivo’s works had great influence over

the northern churches for nearly fifty years, whereas other canonists’ works in

Italy—such as that of Anselm of Lucca—predominated in Mediterranean Europe.

Sometime around 1140, a scholar-monk named Gratian, who taught canon law at

Bologna, published a massive compilation that he called the Concordance of Dis-

cordant Canons but which soon became known simply as the Decretum. Gratian’s

work harmonized both the northern and southern traditions and quickly became

the standard text of canon law. His Decretum was influenced by Aristotle as well

as the Corpus, and in his greatest innovation he cast his work in dialectical form,

organizing his material around a series of specific questions or problems that any

churchman might expect to confront over the course of his career, and then sup-

plying the appropriate legal responses, along with citations of their origins. Here

is one example.

A certain noble lady learned that her hand was sought in marriage by a no-

bleman, to which she consented. But a different man, who was not noble and

was in fact a slave, presented himself to her and pretended to be the noble.

He married her. But then the first man, the noble one, arrived on the scene,

intending to wed her. The noblewoman complained that she was the victim

of deception and wanted to be joined in marriage to the first man, the

nobleman.

Question: Was she already married? If she had believed that the man who wed

her was a freeman and only afterwards learned that he was a slave, may she legally

withdraw from the marriage?

Gratian’s comprehensiveness and pragmatic approach made his compilation by

far the most useful; his use of hypothetical issues also made his text surprisingly

readable, a feature that it still shares with the numerous commentaries made on

it by later canonists.

5

It is important to emphasize that the Decretum was a book

4. Ivo did not know the entire Corpus, but he was familiar with enough of it to understand its orga-

nizational principles.

5. Some of the hypothetical problems he invented were not, considering the pre-reform history of the

Church, all that hypothetical. Consider, for example, the question: “What should be done if the pope

fornicates on the altar of Saint Peter’s basilica?”

THE RENAISSANCES OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY 241

to be used in everyday life, not just to be studied by a handful of scholars in

remote libraries, and it was this characteristic—one that it shared with the Cor-

pus—that made it so central to the revival of medieval life. These books were not

merely products of cultural change, they were engines of change.

By the end of the twelfth century, the intellectual revival of Europe was far

advanced and clearly based on three essential texts: the Sentences for theology, the

Corpus for secular law, and the Decretum for canon law. With these texts one could

say that the medieval world had become in an important sense re-Romanized.

When we turn to science, however, we will see that the influence of the Muslim,

Greek, and Jewish worlds was greater than that of the Roman.

T

HE

R

ECOVERY OF

S

CIENCE

Knowledge of the sciences had never been very sophisticated or widespread in

the early Middle Ages. The Romans themselves had not made many significant

advances in science, being generally more interested in technology and applied

knowledge. Therefore most of what was known in the early medieval centuries

was once again whatever had been translated from the Greeks by a handful of

pre-Carolingian scholars or else written down from various folk traditions. The

seventh-century Spanish bishop St. Isidore of Seville (d. 636) summarized most of

this information, and added some implausible bits of his known, in his encyclo-

pedic compilation called the Etymologies. The book is filled with what appears to

us as nonsense—for example, Isidore suggests that human beings weep more eas-

ily when kneeling in prayer because of the fact that the knees and eyes of an infant

in the womb are closely juxtaposed—but by the standards of the ancient world

his credulity was not egregious. Isidore had intended his encyclopedia to be a

summation of all knowledge up to that point, and for several centuries scholars

in the west were generally content to assume that Isidore had in fact succeeded

in his aim—with the result that virtually no original work was done in the area

of science for four hundred years.

The roots of the scientific recovery in the west lay far to the east, in Baghdad.

The Muslims under the ’Umayyads had scarcely begun to assimilate Hellenic

learned culture by the time they were overthrown by the ’Abbasids. Jihad, not

geometry, was first in their minds. Apart from translating a few alchemical

works—which doubtless appealed to their venal side—they had explored very

little of the great Greek tradition. The ’Abbasids, however, dedicated their court

with equal zeal to the assimilation of Greek and Persian learning, and under the

caliphs Haruˆ n ’al-Rashıˆd (786–809) and ’Al-Ma’muˆn (813–833) they began to

gather scholars, manuscripts, and translators on an enormous scale and establish

a “Library of Wisdom” (khizanat ’al-hikma) in their new capital.

6

Most of the schol-

ars at the “Library of Wisdom” were ethnically Syrian, Armenian, or Arab Chris-

tians—primarily Nestorians

7

—who had already assimilated Greek science and

philosophy into a Christian worldview. A type of spiritual vocabulary had devel-

oped among these scholars that enabled them to bring this knowledge into the

6. It later became known as the bayt ’al-hikma, which means “House of Wisdom.”

7. Nestorians took their name from Nestorius, a fifth-century bishop who had emphasized a distinction

between Christ’s human and divine natures. Mary was mother of the human Jesus, Nestorius argued,

but could in no way be construed as the “mother” of the divine Christ. Condemned at the Council of

Ephesus in 431, Nestorius and his followers went into exile in Egypt. Driven out of Egypt a few years

later, the Nestorians settled in Persia and slowly spread out from there throughout central Asia. They

were the first Christians to reach China, for example. Their familiarity with so many cultures gave them

a well-deserved reputation for assimilation and tolerance.

242 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

new vehicle of the Arab tongue. But not only Greek knowledge. The Baghdad

scholars translated the Persian scientific tradition as well, bringing astronomical,

mathematical, alchemical, and botanical works out of Sanskrit and Pahlavi. As

these newly Arabized texts circulated throughout the empire, more schools, li-

braries, and translation centers were established, and Islamic science began to take

on a more specifically Arab Islamic cast (especially as one moved westward). But

a sense of intellectual pragmatism—as opposed to religious “openness” or toler-

ation—still predominated; thus the ease with which Christian figures like Gerard

of Cremona or Adelard of Bath (see Chapter 9) could move among the translation

centers of ’al-’Andalus was not unique to Muslim Spain but was characteristic of

Islamic higher learning from the start. Surprisingly few Muslim scholars in the

Middle Ages could read Greek (or Sanskrit or Pahlavi). Once the works of the

ancients had been Arabized, they were only read and commented upon in Arabic.

Scholars commonly regarded those earlier languages as debased.

The Islamic world created or popularized at least four landmark institutions

for the advancement of western science: the library, the observatory, the madrasa

(a “school of religious law”) and the paper mill. Libraries, we have seen, came to

dot the empire: There were state libraries in Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, and Se-

ville, and innumerable private libraries. Patronage of science became a hallmark

of Muslim nobility, an emblem of one’s cultivated nature, and in order to attract

scholars to one’s court one had to possess a library in which they could work. For

those engaged in astronomical research one also needed an observatory—fewer in

number than libraries, but impressive in scale. Islamic observatories had perma-

nent staffs, fully equipped libraries, charts, computational tools, and observational

equipment. Too often, however, these observatories were built primarily for the

casting of the horoscopes of the patrons (a residuum of pre-Islamic paganism) and

so were all too seldom used for pure research. Madrasas were another story al-

together. A madrasa was the primary institution of higher education in the Islamic

world; it was where Muslim men studied the Qur’an, the hadith, the shari’a [Is-

lamic laws], and the commentaries upon them under a variety of legal experts.

Although geared specifically toward religious instruction, the madrasas also

taught at least two sciences—mathematics and astronomy—since these were nec-

essary to the observance of Islamic law.

8

A strong though still under-appreciated Jewish element factored into the efflo-

rescence of science. Jewish scholars were among the leaders in Greek-to-Arabic

and Arabic-to-Latin translations, and they were also active in producing original

works of their own, most of which were never translated out of Hebrew in the

Middle Ages. Even prior to the rise of Islam, there were scores of original mathe-

matical and astronomical treatises penned by Jews, primarily in the cities of Byzan-

tium. Most of these early works are anonymous. An exception is an early medical

encyclopedia by Asaph “the Physician” that draws equally on Greek medicine and

Talmudic teaching; it dates from around 600 and was probably written in Syria.

By the twelfth century, Jewish scholars had established a clear preeminence

for themselves in medicine and in some branches of philosophy. Like so much of

the intellectual outpouring of the twelfth-century revival, their medical writings

were intended for practical use in society; such use is shown most clearly by the

8. Complex rules governed the system of inheritance, for example, which made instruction in arithmetic

and algebra necessary, while the requirement for daily prayer at set times created a need for some

understanding of basic astronomy and spherical geometry. The latter were also helpful in determining

the direction of Mecca, toward which all Muslims must turn when they pray.

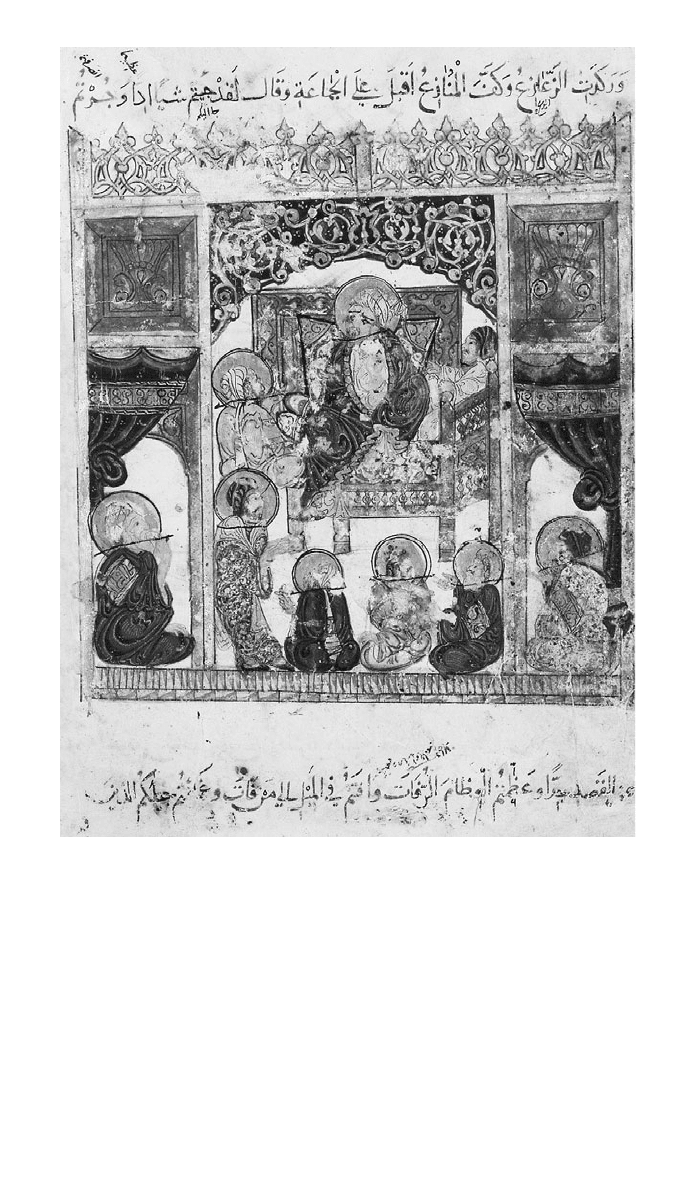

A Literary Reunion. Thirteenth centur y. Maqamat (“Meetings” or

“Encounters”) was one of the most popular fictional works of the

medieval Islamic world. A picaresque account of the adventures of the

semi-scoundrel ‘Abu Za’id, it was written by al-Hariri (1054–1122), an

Arab merchant who lived in Basra. This copy was produced in Baghdad

in the 1240s. (Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

243