Backman Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

204 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

Artist’s re-creation of map of the Mediterranean by ’al-’Idrisi. Twelfth centur y.

This drawing re-creates one of the maps prepared by the celebrated Muslim

geographer ’Abu ’Abudullah Muhammad ’al-’Idrisi in the twelfth century. ’al-

’Idrisi was a scholar attached to the royal court of Roger II of Sicily (1130–

1154), and while in residence at the palace in Palermo he wrote his Kitab ’al-

Malik ’al-Rujjeri (“King Roger’s Book”), the greatest geographical work of the

Middle Ages. Unfortunately, it has never been translated into English. To view

the map correctly, one must invert it. Islamic maps in the Middle Ages

traditionally located south at the top of the map. (Latin Christian maps placed

east at the top, by contrast.) Jerusalem lies at the center. (British Library)

him as the vassal of the Holy See and recognized him as the legitimate ruler of

Apulia and Calabria (the two main regions of southern Italy). After Guiscard’s

death in 1085, his son Roger Borsa inherited his father’s duchy. Meanwhile Guis-

card’s younger brother Roger “the Great Count” began to establish a Norman

power-zone in Sicily, where he had started to campaign as early as 1061. The

Sicilian conquest was complete by 1091 and Norman-style feudalism was imposed.

Roger the Great Count died in 1101 and left Sicily in the hands of his wife Ade-

laide; she retired from the scene when their son Roger II reached manhood and

took over the reins of government in 1112. Roger II also inherited the childless

Roger Borsa’s peninsular territories in 1129; thus was created a vast new realm at

the very heart of the Mediterranean. On Christmas Day 1130, Roger II assumed

royal status with a grand coronation in his capital of Palermo.

This Norman-Sicilian kingdom ended when the dynasty’s direct line died out

in 1194. But while it lasted, it stood out as one of the wealthiest and most powerful

kingdoms in Latin Europe, thanks to the Mediterranean trade that passed through

Sicilian harbors. As in England, the Normans governed their realm with a heavy

hand. Feudal practices and institutions did not fit well in Mediterranean Europe,

where they ran counter to traditions of local autonomy in the countryside; the

urban coastal centers also were accustomed to their own communal ways; and the

polyethnic and multi-religious nature of the kingdom made for a cosmopolitan

but also continually tense social scene. Historians have frequently romanticized

the extent to which the Norman-Sicilian kingdom managed to harmonize these

antagonisms. If Muslims, Greeks, Lombards, Sicilians, and Normans, town-

dwellers, country rustics, and royal administrators found it possible to live to-

A NEW EUROPE EMERGES: NORTH AND SOUTH 205

Mosaic from the central apse of the cathedral at Monreale, Sicily. Twelfth centur y. The

mosaics of Norman Sicily are among the most splendid produced in the whole Middle

Ages. Here we see an image of Christ Pantocrator standing majestically above a scene of

an enthroned Madonna and Child who are flanked by angels, apostles and saints.

Elements of Greek artistic tradition (in the portraiture as well as in the Greek lettering)

combine with some Islamic elements (in the elaborate geometric tracery) to produce a

harmonious and powerful work of art. (Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

gether and to prosper, this was more the “harmony” of people who got along

because they knew that they would face serious reprisals if they did not, than it

was an oasis of mutual respect and tolerance. Nevertheless, for at least a few

generations, these communities from around the Mediterranean did share a com-

mon ground that was not, for once, a battlefield.

206 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Texts

Anonymous. The Poem of El Cid.

———. The Song of Roland.

———. The Usages of Barcelona.

Galbert of Bruges. The Murder of Charles the Good.

Hugo Falcandus. The History of the Tyrants of Sicily.

John of Salisbury. Policraticus.

Ordericus Vitalis. The Ecclesiastical History.

Otto of Freising. The Deeds of Frederick Barbarossa.

———. The Two Cities.

Source Anthologies

Amt, Emilie. Medieval England, 1000–1500: A Reader (2001).

Shinners, John. Medieval Popular Religion, 1000–1500: A Reader (1997).

Strayer, Joseph. Feudalism.

Studies

Abulafia, David. The Two Italies: Economic Relations between the Norman Kingdom of Sicily and the

Northern Communes (1977).

Barber, Richard W. The Knight and Chivalry (1995).

Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (1993).

———. England under the Norman and Angevin Kings, 1075–1225 (1999).

Bisson, Thomas. Cultures of Power: Lordship, Status, and Process in Twelfth-Century Europe (1995).

———. The Medieval Crown of Aragon: A Short History (1991).

Bloch, R. Howard. Medieval Misogyny and the Invention of Western Romantic Love (1992).

Chibnall, Marjorie. Anglo-Norman England, 1066–1166 (1986).

Crouch, David. The Reign of King Stephen, 1135–1154 (2000).

Duby, Georges. The Chivalrous Society (1978).

———. Medieval France (1991).

———. The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined (1980).

———. William Marshall: The Flower of Chivalry (1985).

Dunbabin, Jean. France in the Making, 843–1190 (1985).

Fleming, Robin. Domesday Book and the Law: Society and Legal Custom in Early Medieval England

(1998).

Freedman, Paul. The Origins of Peasant Servitude in Medieval Catalonia (1991).

Gerber, Jane S. The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience (1992).

Glick, Thomas F. From Muslim Fortress to Christian Castle: Social and Cultural Change in Medieval

Spain (1995).

Hanawalt, Barbara A., and Kathryn L. Reyerson. City and Spectacle in Medieval Europe (1994).

Jones, Philip J. The Italian City-State: From Commune to Signoria (1997)

Keen, Maurice. Chivalry (1984).

Lopez, Robert S. The Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages, 950–1350 (1976).

A NEW EUROPE EMERGES: NORTH AND SOUTH 207

Loud, Graham. The Age of Robert Guiscard: Southern Italy and the Norman Conquest (2000).

Matthew, Donald. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily (1992).

Poly, Jean-Pierre, and Eric Bournazel. The Feudal Transformation, 900–1200 (1991).

Reilly, Bernard F. The Medieval Spains (1993).

Reynolds, Susan. Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (1994).

———. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (1984).

Skinner, Patricia. Family Power in Southern Italy: The Duchy of Gaeta and Its Neighbours, 850–1139

(1995).

208

CHAPTER 10

8

T

HE

R

EFORM OF THE

C

HURCH

T

he reform of the Church in the eleventh and twelfth centuries is one of

medieval Europe’s great success stories. Considering the depths to which

the Church had sunk in the tenth century, the fact that by the end of the eleventh

century it was able to re-create itself so completely in terms of its institutional,

doctrinal, intellectual, and spiritual life is deeply impressive. The medieval reform

and its aftereffects is arguably the most revolutionary chapter in Church history;

even the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, some have argued, ef-

fected less fundamental change in Christian life. The reform began at the local

level and worked its way up the social and ecclesiastical hierarchy, gaining mo-

mentum as it progressed, until at the end of the eleventh century it reached the

highest echelons of Church and State. As a result it both reflected and catalyzed

the upsurge of religious enthusiasm of the age. The more the Church reformed, it

seemed, the more thoroughgoing the people expected the reform to become, until

finally the stage was reached, with the pontificate of Gregory VII (1073–1085),

when the reform movement’s own goals were surpassed and an entirely new

ordering of society was proclaimed. In other words, what began as a reform turned

into a revolution of sorts. The end result was a Church as radically different from

what it had been before as Europe’s social and political orderings and institutions

were, as outlined in the preceding two chapters.

The reform of the Church is both an exciting and a cautionary tale. The re-

formers, guided by aspirations for a more meaningful and independent spiritual

life, gradually became enthusiasts for a type of spiritual purity that put at danger

those people outside the orthodox Christian order. On a popular level, champions

of peaceful pilgrimage to holy shrines evolved speedily into armed crusaders de-

termined to rid the world, or at least certain corners of it, of the “enemies of

Christ.” Anti-Semitic violence became widespread, though sporadic, in feudal Eu-

rope, and anti-Semitic prejudices (the same hatred, though with less of the violence

that sprang from it) abounded in the south. Within the Church itself, proponents

of ecclesiastical freedom from State control gave way to ideologues who pro-

claimed the authority of the reformed Church over the State and every aspect of

life within it. And the culmination of the reform came in the bloody struggle for

supremacy between the reformed Church and the equally reformed feudal

monarchies.

There is no question that reform was badly needed. For all its achievements,

the Church had never established itself as a freestanding institution; ever since

Constantine held sway over the Council of Nicaea in the early fourth century, the

churches of Christendom had lain under the more or less direct authority of the

secular state. The Carolingians had continued the practice by every means at their

disposal. Indeed, Charlemagne had made his view of things—the only view that

THE REFORM OF THE CHURCH 209

mattered, as far as he was concerned—perfectly clear in a series of letters he sent

to Pope Leo III, in which he articulated the general policy that it fell to the emperor

to maintain the Church materially, organizationally, and spiritually. The sole re-

sponsibility of the pope, he asserted, is to serve as a kind of personal example of

ideal Christian devotion: to provide a model of piety, prayer, modesty, virtue, and

obedience. But the Holy See is literally powerless. It is the prerogative, but also

the heavy responsibility, of the State to defend, administer, and promote Christian

life. That is why Charlemagne never bothered to consult with Rome before insti-

tuting his system of parish churches, or leading his monastic and liturgical re-

forms, or even deciding a purely theological issue like the debate over the use of

icons in Christian worship.

The Carolingians’ successors viewed it as their right to lord it over their local

churches; and as we saw in Chapter 9, they hurried the Church’s decline by their

pillaging, their simony, and their general lack of concern for maintaining orderly

spiritual life. A gathering of bishops at a Church synod in Trosle in the tenth

century lamented the ruin of the briefly thriving Christendom of Charlemagne’s

time:

Our cities are depopulated, our monasteries wrecked and put to the torch,

our countryside left uninhabited....Just as the first human beings lived with-

out law or the fear of God, and according only to their dumb instincts, so too

now does everyone do whatever seems good in his eyes only, despising all

human and divine laws and ignoring even the commands of the Church. The

strong oppress the weak, and the world is wracked with violence against the

poor and the plunder of ecclesiastical lands....Meneverywhere devour one

another like the fishes of the sea.

As civil society decayed, so did the local churches, which local warlords seized

as sources of revenue. Simony—the sale of ecclesiastical offices—ran rampant, as

did the practice of barons simply installing themselves, their friends, or family

members, in ecclesiastical positions without regard for whether or not those people

were capable of, or even interested in, actually guiding the spiritual lives of their

communities. The rot reached as high as the papacy itself by the tenth century,

when the Holy See was kicked around, bartered, and sold like a trophy among

the families conspiring to dominate local Roman politics. The absolute nadir was

reached with the pontificate of John XII (956–963), an indolent and cruel sensualist

who became pope at the age of eighteen and spent his seven years in office en-

gaged in orgies of sex, violence, incest, arson, and murder. No one mourned when

he died (reputedly of a heart attack after a strenuous bout of lovemaking with a

married woman). Few of his contemporaries were much better, and the dismal

nature of the situation can be glimpsed from the mere cataloging of what befell

those popes who came immediately before and after him: John VIII (872–882) was

knifed to death; Stephen VI (896–897) was strangled while rotting in a prison cell;

Benedict VI (973–974) was smothered while he slept: and John XIV (983–984) was

probably poisoned in the papal retreat at Castel Sant’Angelo. Another pope named

Formosus (891–896) died a natural death but suffered a cruel post-mortem hu-

miliation: His successor, Boniface VI (896), accused Formosus of having been a

heretic and a usurper, and decided, perversely, to place him on trial. Boniface

ordered Formosus’ body to be exhumed. The dead pontiff was brought into the

synod, propped up in the witness chair, convicted on all counts (his inability to

testify in his own defense was taken as evidence of his guilt), and then his corpse

was stripped naked and thrown into the Tiber river. Before throwing the body

210 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

into the river, though, Boniface cut off the finger on which Formosus had worn

the papal ring; he kept the finger as a memento of his bizarre triumph. Boniface

himself lasted on the throne only a few days after this, before he too was dis-

patched.

1

Clearly, something needed to be done.

T

HE

O

RIGINS OF THE

R

EFORM

As seen earlier, Church reform began at the grass-roots level, with masses of com-

moners protesting the violence of the age and the corruption of the churches by

the warlords. The attack on the churches and the oppression of the poor, they

proclaimed, was an offense against God and nature. Outraged by what they saw

happening at all levels, and anguished over doubts about the efficacy of the cor-

rupted clergy’s sacraments, they demanded change in large, though unorganized,

numbers—protesting made possible by the clustering of the rural populace under

manorialism. Rural workers placed themselves under baronial lords’ care and of-

fered their labor in return for protection, but they demanded that the lords release

their stranglehold on the churches. Their “Peace of God” rallies, as they became

known, were the first mass peace movement in western history, and the workers

regarded the “freedom of the church” (libertas ecclesie) an essential component of

that peace.

These protests followed a monastic lead. Since monasteries were often

wealthy, they were singled out for attack by the post-Carolingian warlords. Tiring

of the abuse, Latin monks demanded protection and used, as we saw before, tech-

niques like liturgical cursing in order to persuade grasping barons to grasp less.

The first monastery to receive a guarantee of its freedom was the abbey of Cluny,

near the Aquitanian-Burgundian border, in or around 910. Duke William IX of

Aquitaine, in founding the abbey, made a sweeping declaration of its privileges

and immunities, and relinquished forever control of the monastic house, its lands,

possessions, clients, and tenants. Most importantly, he recognized its right to freely

select its own abbot and declared that

the monks gathered there are not to be subject to my authority or to that of

my relatives, neither to the splendor of the royal sovereignty nor to that of

any earthly power. In fact I warn and admonish everyone, in God’s name and

that of all His saints, and by the terrible Day of Judgment, that no secular

prince, no count, no bishop, nor even the pontiff of the aforesaid Holy See is

to attack the property of these servants of God, nor alienate it, harm it, grant

it in fief, or appoint any prelate over it against these monks’ will.

Cluny’s success inspired other houses to demand the same freedoms from their

masters, and many of those that managed to win out placed themselves under the

authority of the abbot of Cluny, so that by the start of the eleventh century, Cluny

governed a network of several dozen monasteries, both male and female, and the

Cluniac abbot was the single most powerful figure in the Latin Church.

2

1. Shocked by his behavior, a Church synod declared Boniface VI’s pontificate null and void after he

had been only fifteen days on the throne. Indeed, they claimed, his pontificate was never valid since he

had twice been defrocked on moral charges before being installed in St. Peter’s.

2. Cluny grew extremely quickly as enthusiastic monks flocked to it. A new building was soon required,

and before the end of the tenth century Cluny had started construction on a massive new church and

enclosure that was easily the largest in Europe. It was destroyed during the French Revolution, and only

a portion of one transept of the church remains.

211

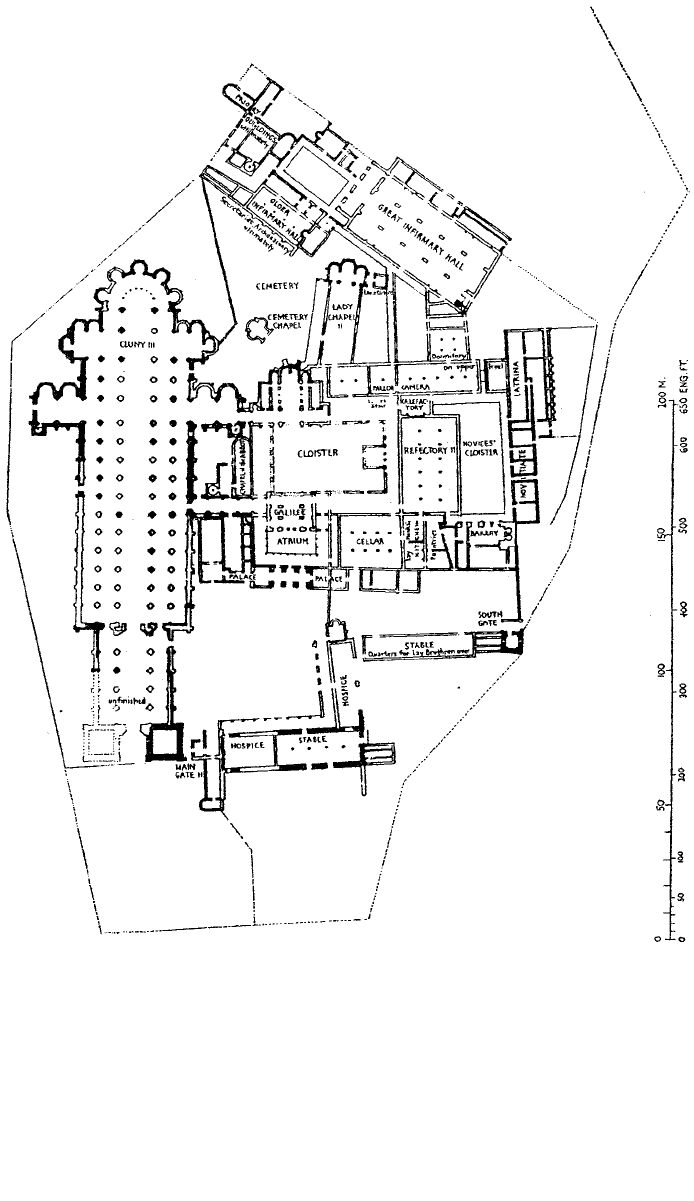

The plan of the monaster y of Cluny. Tenth–twelfth centur y. This is the floor plan of the

monaster y of Cluny as it stood in the middle of the twelfth centur y. The original

building, established two hundred years earlier, was considerably smaller and had

already undergone one major expansion at the end of the eleventh century. This twelfth-

centur y abbey was by far the largest monastery in Western Christendom. It was largely

destroyed during the French Revolution, and only a portion of the north transept

remains today. (Speculum 29 [1954]: 1–43 at page 31, plate 10)

212 THE CENTRAL MIDDLE AGES

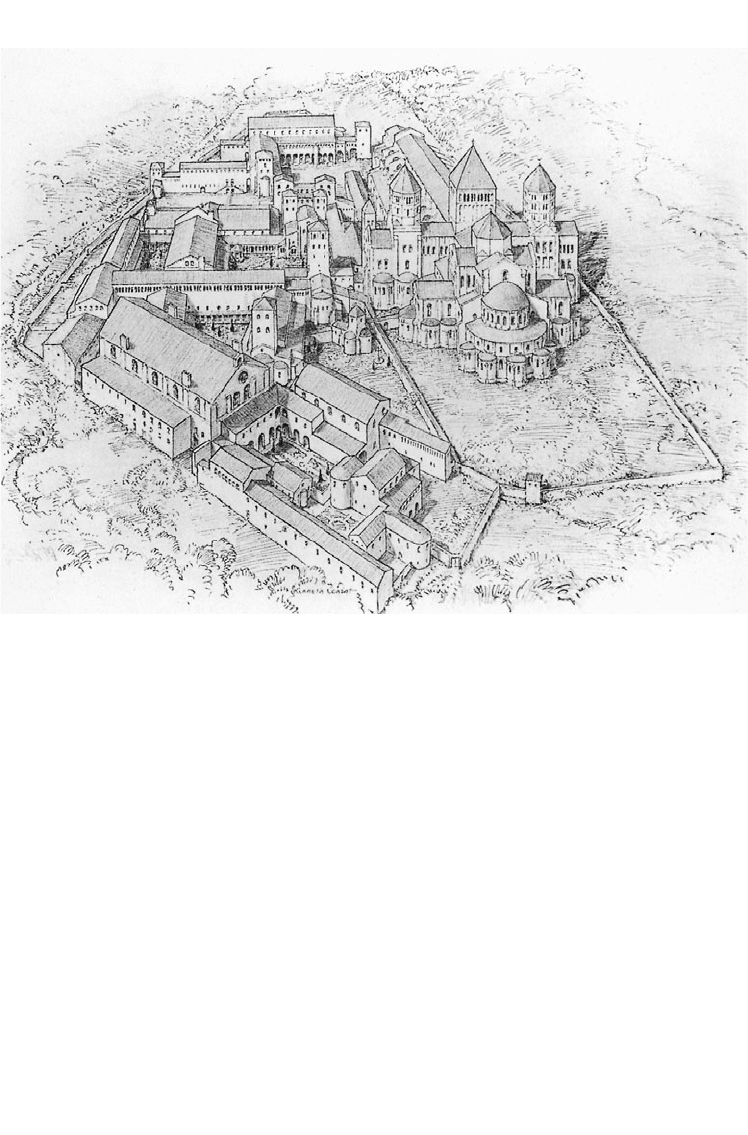

The monastery of Cluny (artist’s re-creation). Tenth–twelfth centur y. This re-

creation of the Cluny monastery gives a powerful sense of its massive size.

(Kenneth J. Conant)

The village and manorial protests—the Peace of God movement—took Cluny

as a model of sorts, and starting around 985 demanded the same basic freedoms

for their parish churches. They had three things going for them. First, the mere

fact that the protesters were now concentrated in clusters of manorial settlement

meant that the lords needed to listen: After all, a crowd of several hundred, and

sometimes several thousand, passionate and torch-bearing protesters represented

a genuine threat to baronial safety. Second, the protesters appealed to the power

of the saints whose relics were the centerpieces of each church, just as the rebel

monks utilized the power of the saints in their liturgical curses. Devotion to the

saints stood at the center of commoners’ spiritual lives, given the paucity of un-

tainted priests in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and by invoking the power of

the relics against the warlords, the Peace of God enthusiasts significantly raised

the emotional pitch of their movement; in other words, it was not only the peo-

ple of any given parish who were outraged by local tyrannies but the saint him-

self, or herself, whose relics adorned the local church. These first two factors

were enough to ensure the movement’s partial success. Thugs who had won

their positions in society by seizing the churches found that they could win pop-

THE REFORM OF THE CHURCH 213

ular support by becoming champions of ecclesiastical reform, a gain that fre-

quently more than made up for whatever they lost in relinquished ecclesiastical

revenues. Their role as church reformers added a new element of religious le-

gitimacy to their emerging social status under the twin influences of feudalism

and manorialism.

But then the third factor weighed in. The bishops of Europe’s developing cities

scurried to seize the reins of the reform movement and provide it with organi-

zation, energy, and ecclesiastical blessing. Promoting the reform certainly raised

their profile. In theory the urban bishops had always had jurisdiction over their

entire dioceses, but in practice very few early medieval bishops had ever had any

meaningful control over the countryside (that is, control over ninety percent of

their flocks) because of the small, primitive, and isolated nature of the cities them-

selves. A bishop’s real power seldom reached much further than the municipal

gates, leaving the rural countryside far more under the indirect influence of the

rural monasteries and the great abbots. To counter this influence, urban bishops

had long relied on a network of surrogate “rural bishops”—also called “core-

bishops” (after the Latin term corepiscopi)—who oversaw the country churches. By

taking control of the Peace and Truce of God, the municipal bishops aimed to

supplant the power of both the rural abbots and the core-bishops. An ecclesiastical

revolution was in the making, one in which bishops, for the first time, were the

dominant figures in the Church.

3

By the start of the eleventh century, the reform movement was clearly in the

hands of these bishops. Their strategic first step was to undermine the authority

of the core-bishops, who enjoyed considerable popularity with the rural faithful.

As early as the middle of the ninth century, a group of bishops gathered at Reims,

in northern France, and compiled an enormous collection of forged documents—

mostly letters from early popes (some of whom, like Evaristus I and Telesphorus

I, were virtually unknown figures of the second century)—which supposedly

proved the absolute authority of bishops over core-bishops (and thus, of town

over countryside). Some of the faked letters even rejected the very notion of a

“core-bishop” as a legitimate representative of the Church. For good measure, the

reformers at Reims also composed papal letters that supposedly recognized the

independence of all bishops from their respective archbishops. All bishops come

under the direct and unique jurisdiction of the papacy, these letters claimed. Eu-

rope’s archbishops were outraged, but the pope in Rome could not have been

happier. Thus from the very start of the reform, the fates of Europe’s bishops and

of the papacy were united. The Reims documents formed the basis of episcopal

privilege for six hundred years, until they were discovered to be forgeries in the

Renaissance; but throughout the rest of the Middle Ages they were believed to be

the legitimate work of an ancient Church scribe named Isidore Mercatus, and

hence they are now known as the Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals.

Some readers may be surprised to find devout ecclesiastical reformers en-

gaged in wholesale lying (but then to others it may be exactly what they would

expect). The great Church Reform was in many respects a “golden age” of forgery,

with scribes on all sides churning out reams of phony papal letters, land grants,

3. As an index of how important this shift was, one should note that with the exception of the miserable

politicos who abused the office in the tenth century, the great majority of those who held the papacy in

the first thousand years of Christianity had previously been a monk; in the second thousand years of

Christian history, virtually every pope has been a bishop before ascending to the Holy See.