Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

316 Freedom Riders

These and other related developments were more than enough to con-

vince Mississippi authorities that the Freedom Rider onslaught would con-

tinue for the foreseeable future. As far as they were concerned, the only good

news on the horizon was an FRCC decision to send at least some of the

impending Freedom Rides to locations other than Mississippi. During a four-

day hiatus, from June 12 to 15, the only Freedom Rider to arrive in the state

was Danny Thompson, a white college student from Cleveland, Ohio, who

had missed a connecting bus in Memphis. After straggling into Jackson on

Wednesday morning and conducting a one-man test of the segregated facili-

ties at the Greyhound terminal, he ended up in the city jail with the other

white Riders.

By that time, both the city and county jails were jammed with Freedom

Riders, and local officials had already made plans to transfer some of the

Riders to the state prison farm at Parchman, 120 miles northwest of Jackson.

On Monday, June 12, the Hinds County Board of Supervisors authorized

Sheriff Gilfoy to transfer as many prisoners to Parchman “as he may deem

necessary to relieve and keep relieved the crowded conditions in the county

jail.” White supremacist leaders immediately hailed the prospect of transfer-

ring the Freedom Riders to the dreaded confines of Parchman, where the

Riders would finally encounter the full force of Mississippi justice. The edi-

tor of the Jackson Daily News even penned an invitation sarcastically touting

the benefits of spending time at the state’s most notorious prison:

ATTENTION: RESTLESS RACE MIXERS

Whose Hobby is Creating Trouble.

Get away from the blackboard jungle.

Rid yourself of fear of rapists, muggers, dopeheads, and

switchblade artists during the hot, long summer.

FULFILL THE DREAM OF A LIFETIME

HAVE A “VACATION” ON A REAL PLANTATION

Here’s All You Do

Buy yourself a Southbound ticket via rail, bus or air.

Check in and sign the guest register at the Jackson City Jail. Pay a nominal

fine of $200. Then spend the next 4 months at our 21,000-acre Parchman

Plantation in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. Meals furnished. Enjoy the

wonders of chopping cotton, warm sunshine, plowing mules and tractors,

feeding the chickens, slopping the pigs, scrubbing floors, cooking and wash-

ing dishes, laundering clothes.

Sun lotion, bunion plasters, as well as medical service free. Experience the

“abundant” life under total socialism. Parchman prison fully air-cooled by

Mother Nature.

(We cash U.S. Government Welfare Checks.)

Make Me a Captive, Lord 317

By Wednesday, June 14, it appeared that the transfer to “the most fabled

state prison in the South” was imminent. Parchman superintendent Fred Jones

had already made room for more than a hundred Freedom Riders by clearing

out the prison’s maximum security unit, and he assured Hinds County offi-

cials that he could accommodate four hundred more as soon as a new first

offenders’ camp was completed in late June. After learning that the first trans-

fer might come as early as Thursday morning, Jones insisted that he and his

guards were eager to “welcome” the Freedom Riders to Parchman.

17

As Mississippi officials prepared for the transfer to Parchman, the Free-

dom Rides also took a new turn in Washington, where CORE field secretary

Genevieve Hughes held a press conference on Monday, June 12. Still recov-

ering from her harrowing experiences in Alabama, but now flanked by more

than thirty volunteers sporting large blue and white buttons identifying them-

selves as “Freedom Riders,” Hughes announced that two special groups of

Riders would depart from the nation’s capital within twenty-four hours. The

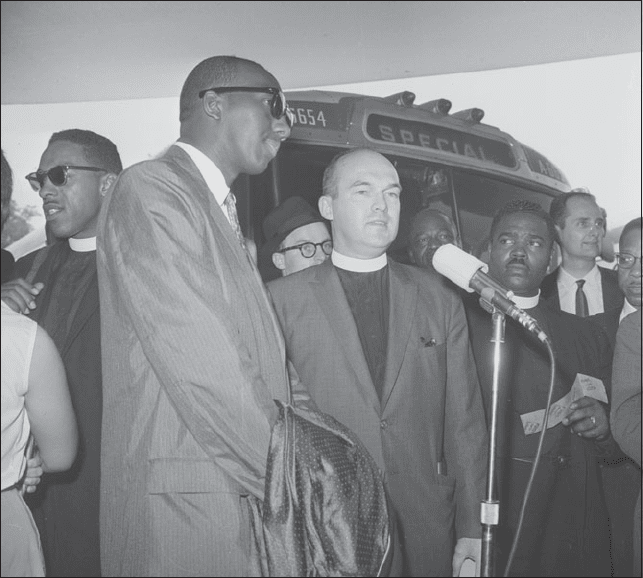

The Reverends Perry A. Smith and Robert J. Stone speak to reporters before depart-

ing from Washington on the Interfaith Freedom Ride, June 13, 1961. The other

Interfaith Freedom Riders standing in front of the bus are (left to right) the Rever-

ends Arthur L. Hardge, Robert McAfee Brown, Donald Alstork, George Leake,

A. McRaven “Mack” Warner, and John W. Collier. (Bettmann-CORBIS)

318 Freedom Riders

first group, consisting of eighteen clergymen—fourteen Protestant minis-

ters and four rabbis—had agreed to undertake an “Interfaith Freedom Ride”

from Washington to Tallahassee, Florida. The second group, numbering

fourteen—seven blacks and seven whites—represented an eclectic assortment

of teachers, students, doctors, and representatives of organized labor. Tak-

ing a more easterly route than the Interfaith Ride, they planned to conduct

tests along the Atlantic seaboard, stopping in Wilmington, North Carolina,

Charleston, South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Florida, and ending up in

the Gulf Coast city of St. Petersburg. It had been more than five weeks

since the original CORE Freedom Ride had left Washington, but now the

Southeastern states would get a second chance to demonstrate compliance

with federal law. Flashing her effervescent smile, Hughes optimistically

predicted that the new Riders would “be given service at all stops but Talla-

hassee and Tampa.”

On Tuesday both groups did indeed reach their first-night stopovers in

North Carolina without any major problems. The Interfaith group spent the

night at Shaw University in Raleigh, where SNCC had been founded four-

teen months earlier, and the second group stayed at a black hotel in the coastal

city of Wilmington. “We have been treated with the utmost courtesy,” the

Reverend Gordon Negen, pastor of Manhattan’s Christian Reformed Church,

told reporters in Raleigh: “We hope it will be that way all the way.” When

the second group arrived in Wilmington, there was a surly crowd of 150

whites waiting outside the local bus station, but a strong police presence kept

the crowd at bay. On Wednesday morning the Wilmington Riders split into

two groups that planned to reunite in Charleston after conducting tests in

Myrtle Beach and other low-country communities. In Charleston, and else-

where in South Carolina, the Riders received what one reporter called “a

cool but orderly reception,” and the Riders spent the night in the city of

secessionist memories without incident.

18

Meanwhile, the Interfaith Riders made their way to Sumter, South Caro-

lina, where they were greeted by several local CORE stalwarts, including the

veteran Freedom Rider Herman Harris. Before arriving in Sumter, the Riders

were warned that the town was fraught with tension stemming from Harris’s

claim that he had been abducted by four white Klansmen after returning

from New Orleans. Blindfolded and taken to an isolated clearing in the woods,

he was subjected to a night of terror. After forcing him to strip, his assailants

carved crosses and the letters “KKK” into his legs and chest and threatened

to castrate him for challenging white supremacist orthodoxy. Even though

his abductors vowed to kill him if he reported what had happened, Harris

eventually asked the Justice Department to conduct an investigation. When

the Interfaith Riders arrived in Sumter on Wednesday, June 14, the matter

was still pending. But a dismissive response from state and local officials—

South Carolina Governor Fritz Hollings called Harris’s story “a hoax”—had

all but invited local white supremacists to stand guard against any additional

civil rights agitation.

Make Me a Captive, Lord 319

320 Freedom Riders

In this atmosphere, some form of confrontation was virtually inevitable,

as the Riders’ first stop in Sumter demonstrated. Stopping for lunch at the

Evans Motor Court a few miles north of town, the Riders encountered “twenty

or thirty toughs” and an angry proprietor who blocked their path. Informing

them that he had “no contract with Greyhound” and that he was “not sub-

ject” to any Supreme Court decisions, he drawled: “We been segregated, and

that’s the way we gonna stay.” Moments later the local sheriff stepped for-

ward to back him up, literally shouting: “You heard the man. Now move

along. I’m ready to die before I let you cross this door.” As the stunned Rid-

ers quickly considered their options, another local man bragged: “I got a

snake in my truck over there I’m just dyin’ to let loose among them nigger

lovin’ Northerners.” Even this threat did not faze some members of the

Interfaith group, but the majority prevailed and all eighteen Riders

reboarded the bus. Later, at the Sumter bus terminal, the Riders had no

trouble desegregating the white waiting room and restrooms, and their spir-

its were further renewed at an extended mass meeting at the same black

church that had welcomed the original CORE Riders in mid-May. Never-

theless, the earlier retreat continued to bother many in the group, including

one minister who vowed to return someday to complete the unfinished busi-

ness at the motor court.

19

Just before midnight the Riders left Sumter behind and pressed on to

Savannah and Jacksonville, where they found the local bus terminals fully

integrated, at least for the moment. In the latter city, the Riders shared a

breakfast with an interracial group of five NAACP activists. Sponsored by

the Florida NAACP, these self-styled “fact-finders” were essentially local

Freedom Riders who had been traveling around the state testing various fa-

cilities. The unexpectedly cordial reception that they and the Interfaith Rid-

ers received in Jacksonville reflected days of behind-the-scenes maneuvering

by Florida governor Farris Bryant. Earlier in the week Robert Kennedy had

called Bryant to urge him to avoid any unnecessary confrontations with the

Riders, and Bryant had taken the advice to heart. Accordingly, he dispatched

personal representatives to each of the major communities along the Riders’

scheduled route. In Florida, unlike Alabama, the official policy was polite

indifference, a strategy plotted by a governor who did not want his state to

end up in the national headlines. Much of the state, particularly northern

Florida, was rigidly segregated by law and custom, but Bryant and others

decided that the best way to preserve that segregation was to make sure that

the Freedom Riders traversed the state without provoking open hostility or

violence.

This goal seemed well in reach on Thursday morning as the Interfaith

Riders headed west toward Tallahassee and the Florida Panhandle on the

final leg of their journey. Along the way they ran into a bit of trouble in the

county-seat town of Lake City, where waitresses at a snack bar refused to

serve a racially mixed group of clergymen, but they encountered less hostil-

Make Me a Captive, Lord 321

ity than was expected at the Tallahassee Trailways terminal, where they once

again shared a meal with the NAACP fact-finders. The situation was tenser

later in the day at the Greyhound terminal, where the Riders had to sidestep

a crowd of angry protesters, two of whom attacked an interracial testing team

trying to desegregate a white restroom; with the grudging assistance of the

Tallahassee police, a second attempt to desegregate the restroom proved suc-

cessful. In the terminal restaurant, the management saw to it that black Free-

dom Riders were served by black waiters and white Riders by white waiters,

but the fact that all of the Riders were served in the same room took at least

some of the sting out of what was clearly a halfhearted effort at compliance

with federal law. Satisfied that they had established an integrationist beach-

head in the capital of the Sunshine State, the eighteen Interfaith Riders de-

cided to fly home that afternoon.

20

Accompanied by several local black activists, the Riders arrived at the

Tallahassee airport in time to conduct a test at the airport’s white restaurant.

A relatively new facility constructed with the help of federal funds but man-

aged by a private company, the restaurant had never served black patrons, as

a black CORE staff member turned away in April had discovered. That seg-

regated dining was still the rule on June 15 became abundantly clear when

local authorities stymied the proposed test by simply closing the restaurant

as soon as the Riders arrived at the airport. Tired and disgusted, eight of the

Riders soon flew home as planned. The other ten, however, decided to remain

at the airport until the restaurant reopened and served them in compliance

with federal law. Among the ten were Robert McAfee Brown, a distinguished

Presbyterian theologian who held a chaired professorship at Union Theo-

logical Seminary; Ralph Roy, a longtime CORE member and pastor of the

Grace Methodist Church in New York City; three black ministers—John

W. Collier Jr. of Newark, New Jersey, Arthur Hardge of New Britain, Con-

necticut, and Petty McKinney of Springfield, Massachusetts; and two young

reform rabbis from northern New Jersey—Martin Freedman, a friend and

protégé of Bayard Rustin’s, and Israel “Si” Dresner, an outspoken Brooklyn-

born activist later dubbed “the most arrested rabbi in America.”

21

The press initially reported the Riders’ action as a hunger strike, but

from the outset their common goal was to break the local color bar by eating

together at the airport restaurant. Before they were through they discovered

just how difficult this seemingly simple task could be. As Burke Marshall had

conceded in a lengthy interview on June 11, enforcing desegregation at avia-

tion facilities was a “knotty problem” complicated by clever uses of private

funding and the fact “that the Federal Aviation Agency was not a regulatory

agency in the sense that the I.C.C. was.” But, as several members of the

group explained to reporters, such legalisms were of little concern to ten

clergymen who knew right from wrong. Even so, they sent a telegram to the

chairman of the ICC urging federal intervention. By nightfall their stubborn

protest had drawn a large crowd of angry whites, but they refused to budge

322 Freedom Riders

until the airport itself closed at midnight. Taken to a black Baptist church in

downtown Tallahassee, they spent an emotional hour discussing racial and

social justice with a gathering of local civil rights activists, many of whom

were veterans of the 1956 Tallahassee bus boycott and other civil rights cam-

paigns. Later the Riders slept on the floor as two of the state policemen who

had escorted the Riders from the airport stood guard across the street.

At 7:30 the next morning, they returned to the airport to resume the

vigil outside the terminal restaurant. Joined by several local activists and sur-

rounded by police and a bevy of reporters, they remained there for nearly

five hours. After nervously monitoring the situation throughout the morn-

ing, Governor Bryant called Robert Kennedy to ask for help. “You’ve got to

get these people out of here,” Bryant pleaded. “I’ve done all I can do.” Con-

cerned about the Riders’ safety and fearful that he had another white su-

premacist siege on his hands, Kennedy asked Bryant to hold things together

for an hour or two while he tried to persuade the Riders to suspend their

protest. Minutes later, around 12:30, Burke Marshall was on the phone with

John Collier, but their brief conversation ended abruptly when Tallahassee

city attorney James Messer ordered the Riders to leave the airport within

fifteen seconds. When Collier and the others stood their ground, the police

moved in and arrested them for unlawful assembly. The police also arrested

three local civil rights leaders—CORE veteran Priscilla Stephens, the Rev-

erend Stephen Hunter, and Jeff Poland, a student sit-in organizer at Florida

State University. When Stephens—who along with Poland had only recently

been released from jail—objected to the arrests, the police charged her with

interfering with an officer and resisting arrest.

By midafternoon all thirteen defendants were ensconced in the city jail,

a run-down and overcrowded facility that shocked those who had never seen

the inside of a Southern lockup. “The conditions in the jail were forebod-

ing,” Ralph Roy wrote later. “Our black colleagues were separated from us,

of course, though we could communicate by yelling through a wall dividing

us by race. They were received as heroes among their fellow prisoners. In

contrast, inmates with us were initially hostile. We were, to most of them,

interlopers from the north, even damnable traitors to the white race. . . .We

were crowded into an area designed to house twenty-four and there were,

altogether fifty-seven. There was one sink, one toilet, and one shower. . . .

The food was slop. After a twenty-four hour fast, our supper Friday evening

was a piece of gingerbread and a cup of cold, weak coffee.”

22

While Stephens, Hunter, Poland, and the “Tallahassee Ten,” as they

came to call themselves, were dealing with the miserable conditions at the

capital city jail, other Freedom Riders were running into trouble in the cen-

tral Florida community of Ocala, Governor Bryant’s home town. When sev-

eral black Riders tried to enter a white cafeteria at the Ocala Greyhound

station, two white men shoved them backward. The police immediately in-

tervened, ordering the Riders to return to the bus. Three of the seven Riders

Make Me a Captive, Lord 323

involved—Leslie Smith, a black minister from Albany, New York; Herbert

Callender, a black union leader from the Bronx; and James O’Connor, a white

economics instructor at Barnard College in Manhattan—refused to comply

with the order. Charged with unlawful assembly and failure to obey a police

officer, they were released on bond later in the day. By that time their fellow

Riders, after successfully desegregating the Ocala terminal’s white restrooms,

had proceeded southward to Tampa and St. Petersburg, the final destination

for many of the Florida-bound Freedom Riders. Before the day was over the

two Gulf Coast cities had weathered three different Freedom Rides with less

difficulty than most local observers had anticipated.

In St. Petersburg, a fabled resort and retirement center that had recently

been rocked by a controversy over the proposed desegregation of accom-

modations for Major League baseball players during spring training, one white

man was arrested for harassing the Reverend Macdonald Nelson, a local black

minister who was part of a welcoming committee at the downtown Grey-

hound station. Otherwise the city took the arrival of the Freedom Riders in

stride, thanks in part to the prodding of the St. Petersburg Times, the South’s

most liberal daily newspaper. After eating lunch at the Greyhound station

without incident, four of the Riders participated in an afternoon workshop at

a local black Baptist church. During the workshop Ralph Diamond, a black

labor leader from New York City, urged local activists to build upon the

Freedom Riders’ positive experience in St. Petersburg. “We will lose what

we’ve gained if this is not followed up locally,” Diamond declared. “It must

get to the point where it will become a natural thing for the two races to sit

together at counters. When the tenseness wears off, you’ll find there will be

no problem.”

Speaking to an integrated audience at a mass meeting that evening, the

Reverend William Smith, the president of the biracial St. Petersburg Coun-

cil on Human Relations, repeated Diamond’s warning. “Unless we continue

the work of these courageous people by using all the facilities of our bus

stations,” the black minister exhorted, “I’m afraid the freedom riders’ trip

may have been in vain.” Two days later, after the Riders had flown back to

New York, the St. Petersburg Times offered a congratulatory editorial. “We

did not expect any trouble here,” the editors insisted. “We didn’t get it. And

had it come, law enforcement was ready. This is a healthy situation of which

we can all be proud. . . . We can’t afford, for our own good, to permit uncon-

stitutional practices, head-turning law enforcement, discrimination and vio-

lence anywhere in this country.” Such rhetoric was an encouraging sign for

movement leaders, but at the same time they knew all too well that St. Pe-

tersburg was a long way from Jackson—and Tallahassee.

23

The conclusion of the Florida Freedom Rides was less satisfying for

the Tallahassee Ten, who were arraigned at a city court on Saturday morn-

ing. Released on bond, they flew to Newark for a four-day respite before

returning to Tallahassee for a June 22 trial. During the trial, the three local

324 Freedom Riders

defendants—Stephens, Poland, and Hunter—were acquitted of unlawful as-

sembly, but Judge John Rudd was unmoved by attorney Tobias Simon’s de-

fense of the Freedom Riders’ determination to desegregate the airport

restaurant. Offering the Riders a choice between thirty days in jail and a five-

hundred-dollar fine, Rudd scolded them for coming “here for the whole pur-

pose of forcing your views on the community.” “If I thought for one minute

that you came here on a noble, Christian purpose and acted accordingly,”

Rudd continued, “you would not be here now. Stop and think when you go

back home and check the records of crime, prostitution and racial strife there

compared to Tallahassee. Then clean up your own parishes, and you’ll find

you have more than you can take care of.” Stephens also received a tongue-

lashing and even harsher punishment. Though acquitted on the unlawful

assembly charge, she was convicted of resisting arrest and sentenced to five

days in jail, plus thirty more for violating probation related to a 1960 sit-in

conviction. Stephens appealed her conviction, as did the Tallahassee Ten,

Nine members of the Tallahassee Ten hold a press conference after returning

to Florida to serve out their sentences, August 4, 1964. Seated, from left to right:

the Reverends Robert McAfee Brown and John W. Collier and Rabbi Martin

Freedman. Standing, from left to right: Rabbi Israel Dresner and the Reverends

Petty D. McKinney, Robert J. Stone, A. McRaven “Mack” Warner, Arthur L.

Hardge, and Wayne Hartmire. (Florida State Archives)

Make Me a Captive, Lord 325

and the legal wrangling over the airport arrests continued for years. Although

a state circuit court overturned Stephens’s conviction in 1962, the Freedom

Riders’ case dragged on until 1964, when the same circuit court judge and

the Florida Supreme Court denied their appeal. The United States Supreme

Court refused to overrule the Florida courts, which sent the case back to

Judge Rudd for final disposition and sentencing. In the end, one of the ten

defendants avoided jail by agreeing to pay a fine. But the other nine returned

to Tallahassee in August 1964 to serve brief jail terms—and, following their

release, to eat triumphantly at the same airport restaurant that had refused to

serve them in 1961.

24

IN THE EARLY HOURS of Thursday, June 15, only minutes before the Interfaith

Riders left Sumter, a new and dark chapter of the Freedom Rider saga opened

in Mississippi. The first transfer of Freedom Riders to Parchman began just

after midnight as forty-five male prisoners—twenty-nine blacks and sixteen

whites—were loaded into a convoy of trucks. After the Riders were herded

into what amounted to “airless, seatless containers,” in John Lewis’s words,

“the doors were closed, locked, and in utter darkness we were driven away,

bracing ourselves against one another, as the trucks lurched around turns, the

drivers doing the best they could to slam us into the walls. We had no idea

where we were going.” As the convoy lurched northward, however, at least

some of the Riders began to suspect that they were on Highway 49, the road

to the Delta and the dreaded Parchman farm. It was a road that thousands of

unfortunate Mississippians had taken since the prison’s construction in 1904,

and very few had survived the experience without suffering lasting physical

and emotional scars. Many, of course, did not survive at all. “Throughout

the American South, Parchman Farm is synonymous with punishment and

brutality . . .” historian David Oshinsky observed in 1996, and the farm’s

gruesome reputation for unfettered violence was, if anything, even more wide-

spread and deserved in 1961 when the Freedom Riders were there. As a char-

acter in William Faulkner’s 1955 novel The Mansion put it, Parchman was

“destination doom.”

25

When the Riders arrived at the prison at dawn, there was just enough

light to see the outlines of their new home—a world bounded by “a barbed-

wire fence stretching away in either direction.” There were also “armed guards

with shotguns,” Lewis recalled. “And beyond the guards, inside the fence, a

complex of boxy wooden and concrete buildings. And beyond them, nothing

but dark, flat Mississippi delta.” As the Freedom Riders’ eyes adjusted to the

light, the imposing figure of Superintendent Fred Jones appeared at the gate.

“We have some bad niggers here,” Jones drawled. “We have niggers on death

row that’ll beat you up and cut you as soon as look at you.” Moments later

the guards began pushing the Riders toward a nearby processing building,

but the forced march was soon interrupted by a scuffle in the rear of the

line. Terry Sullivan and Felix Singer, two white Freedom Riders who had