Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

286 Freedom Riders

each defendant to a two-hundred-dollar fine and a suspended sixty-day jail

term. Whether he regarded the suspension of jail time as leniency or simply

as an efficient means of ridding the state of unwelcome visitors was unclear,

but the look on his face suggested that he never wanted to see them or their

kind again.

23

Prior to the trial, the Freedom Riders had announced their intention to

remain in jail until Mississippi authorities agreed to recognize the legality of

desegregated interstate transit, but Spencer and other Mississippi officials

held out some hope that at least some of the Riders were bluffing. In truth,

there were those among the Riders who questioned the strategy of “jail–no

bail.” For some, spending sixty days, or even one more night, in a Mississippi

jail was a frightening prospect. Nevertheless, when the convicted Freedom

Riders met with their attorneys on Friday evening, no one spoke in favor of

a mass bail-out. Some, like Lucretia Collins, who had promised to return to

Nashville for the May 29 graduation exercises at Tennessee State, had per-

sonal reasons for paying her two-hundred-dollar fine and accepting a sus-

pended sentence, and CORE officials decided that the four Freedom Riders

from Louisiana—David Dennis, Jerome Smith, Doris Castle, and Julia

Aaron—were needed in New Orleans to set up an FRCC recruitment and

training center. But there was general agreement that the rest of the Riders

could serve the cause best by remaining in jail. Later in the evening, while

the Jackson NAACP held a mass meeting at a black Masonic temple to pro-

test the convictions, local authorities transferred the Riders across the street

to the Hinds County Jail. With reports circulating that at least two new groups

of Nashville-based Freedom Riders were about to leave for Jackson, the de-

fenders of white Mississippi’s most cherished traditions wanted to be ready

for the next invasion.

24

On Friday afternoon, following the organizational meeting of the FRCC,

King had told reporters that there would be a “temporary lull” in the Free-

dom Rides while movement organizers set up recruiting and training centers

around the South. But the predicted lull did not last long. Hoping to sustain

the movement’s momentum, Nash returned to Nashville on Saturday morn-

ing to help Leo Lillard and Pauline Knight finalize the arrangements for a

new round of Rides. By Saturday afternoon, thirteen new Freedom Riders

were ready to go. Just after lunch, Knight, Allen Cason (who had narrowly

escaped serious injury in Montgomery the previous Saturday), and two other

Riders boarded a bus for Montgomery, with plans to travel on to Jackson. At

5:15 a second group of nine Riders—all students at Tennessee State—boarded

a Greyhound headed for Jackson via Memphis. Like Cason, six of the nine

Tennessee State Greyhound Riders had participated in the recent Birmingham-

to-Montgomery Ride, and even though they had returned to Nashville ear-

lier in the week to take their final exams, all still faced the possibility of

expulsion for their participation in the Freedom Rides.

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 287

While the new Riders were en route, Lillard issued a deliberately con-

fusing statement that puzzled many observers. After refusing to confirm that

the Riders planned to conduct desegregation tests once they arrived in Jack-

son, he coyly suggested to reporters that both groups were “just normal col-

lege students going home from schools here.” Their behavior was simply in

keeping with the national NAACP’s call, issued the day before, for college

students “to return home at the end of the school year on a ‘nonsegregated

transportation basis.’ ” Speaking in New York, Roy Wilkins had urged stu-

dents to “sit where you choose on trains and buses” and to “use terminal

restaurant and other facilities without discrimination.” Anxious officials in

Alabama and Mississippi did not know what to make of Lillard’s suggestion

that the Nashville students were not necessarily “Freedom Riders,” espe-

cially when a SNCC spokesperson in Atlanta was calling for a mass of volun-

teers to join the Freedom Rider movement. Representing both SNCC and

FRCC, Ed King told reporters on Saturday afternoon that three interracial

groups of Freedom Riders were on their way to Jackson, and many others

would soon follow. According to King, SNCC members in sixteen states and

the District of Columbia were mobilizing for an all-out assault on segregated

transit. Before long, King predicted, there would be hundreds of new Free-

dom Riders committed to “jail–no bail,” students picketing Greyhound and

Trailways terminals across the South, and a flood of telegrams to President

Kennedy and the Justice Department “demanding protection for interstate

passengers from arrests by local law-enforcement officers on segregation

charges.” Like Lillard, King refused to provide confirmation that the Riders

presently headed for Jackson planned to violate local segregation laws, but

he hinted that desegregation tests would begin as soon the Riders could co-

ordinate their plans with local movement leaders “on the scene.”

25

In the case of Knight’s group, such coordination led to the addition of

four more Freedom Riders. Arriving in Montgomery at 8:25

P.M., the four

Nashville students soon joined forces with two members of the Washington-

based Nonviolent Action Group, William Mahoney and Franklin Hunt, and

two white students from Wilberforce, Ohio, David Fankhauser and David

Myers. After spending the night as the guests of Montgomery Improvement

Association leaders, the eight Riders made their way to the Trailways termi-

nal, which was still under heavy guard. In contrast to the riotous scene of the

previous weekend, the terminal was almost empty, and the Riders had no

trouble desegregating the terminal’s restaurant and restrooms. When Sher-

iff Butler was later asked why he had not arrested the most recent violators of

Montgomery’s segregated facilities ordinance, he replied: “None of us saw

it. We were getting some sleep when the call came.” In truth, local and state

officials, eager to escort the Riders out of Montgomery, had made sure that

there would be no arrests, and no trouble. “It’s so calm,” Knight remarked,

“it’s almost unbelievable in comparison with what happened [last] Saturday.

I just hope people are peaceful in their hearts.” When Knight and the others

288 Freedom Riders

boarded the bus for Jackson a few minutes later, Sheriff Butler, General

Graham, and a line of highway patrol cars moved into position to escort the

bus to the Mississippi border. Though more modest than Wednesday’s op-

eration, the Sunday morning convoy reached the border without incident

and proceeded on to Jackson, arriving at 1:30

P.M.

By the time the Trailways group arrived in Jackson, the Greyhound group

was already in jail. After a late-night stop in Memphis, the Greyhound de-

parted for Mississippi around 1:15 in the morning and arrived in Jackson just

before dawn. Although the Greyhound Riders, unlike the Trailways Riders,

traveled without a police escort, local authorities were waiting for them at the

terminal. As soon as they walked into the white waiting room, the nine stu-

dents were arrested for breaching the peace and led to a waiting paddy wagon.

Before entering the wagon, one of the students handed a pile of pamphlets on

“Fellowship and Human Rights in America” to a detective who jokingly prom-

ised to distribute them. Otherwise the arrests followed the same pattern as

those of the previous Wednesday. “They passed us right on through the white

terminal, into the paddy wagon, and into jail,” Fred Leonard recalled. “There

was no violence in Mississippi.” Eight hours later, Knight and the Trailways

group suffered a similar fate, bringing the total number of arrested Mississippi

Freedom Riders to forty-four. Arresting Freedom Riders, as one local editor

complained on Monday morning, was becoming “monotonous.”

26

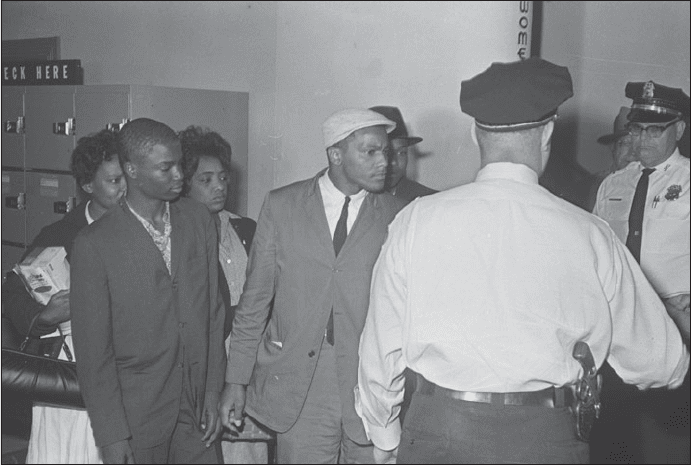

Freedom Riders are placed under arrest at the Jackson Greyhound terminal,

Sunday, May 28, 1961. From left to right: Frances Wilson, Fred Leonard,

Catherine Burks, Lester McKinnie, and Clarence Wright. (Bettmann-CORBIS)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 289

He was not alone in his feelings. Even before news of the latest arrests

hit the papers, there were signs that many Americans—and not only white

Mississippians—were growing tired of the Freedom Riders. In a stinging

Sunday morning editorial, the New York Times declared that “the battle against

segregation will not be won overnight nor by any one dramatic strategy. The

Freedom Riders, for all their idealism, now may be overreaching themselves.

There is a danger that if their offensive is continued at the present pace,

exacerbated feelings on both sides could lead to tragic results in which the

extremists could overwhelm the men of moderation on whom the real solu-

tion will ultimately depend. . . . The Freedom Riders have made their point.

Now is the time for restraint, relaxation of tension and a cessation of their

courageous, legal, peaceful but nonetheless provocative action in the South.”

The Times certainly did not speak for all white Americans, and there were

still many voices urging the Freedom Riders to press their case, including an

unrepentant William Sloane Coffin, who reminded his Sunday morning con-

gregation at Yale that “any return to normalcy means a return to injustice.”

In the nation as a whole, however, the tide of public opinion seemed to be

running against the Riders. Many Americans, particularly outside the South,

felt conflicted, as sympathy for civil rights vied with disapproval of the Free-

dom Riders’ tactics. Even among those who were strongly sympathetic to

the civil rights movement, there seemed to be a rising wave of sentiment in

favor of a moratorium or cooling-off period. Indeed, with the president’s

departure for Paris scheduled for Tuesday evening, the argument for na-

tional solidarity seemed especially compelling.

27

ON MONDAY, MAY 29, the prospects for a cooling-off period did not look

good. On the contrary, the situation appeared to be heating up on all fronts.

In Jackson, the day began with the pre-dawn transfer of twenty-two Free-

dom Riders to the Hinds County Penal Farm, seventeen miles south of the

city. Judging by the smiles on the faces of their guards, the Riders had good

reason to fear the move. As one black inmate at the county jail told Farmer:

“That’s where they’re gonna try to break you. They’re gonna try to whip

your ass.” After Jack Young seconded the inmate’s warning—“That place is

rough. You’re going to have trouble there,” he predicted—Farmer asked him

to let the FBI know what was going on. The actual scene at the penal farm

turned out to be even worse than the Riders had anticipated. “When we got

there,” Frank Holloway recalled, “we met several men in ten-gallon hats,

looking like something out of an old Western, with rifles in their hands,

staring at us as if we were desperate killers about to escape.” This sight drew

a sardonic smile from Holloway, but what happened next was anything but

humorous. As he described the scene: “Soon they took us out to a room, boys

on one side and girls on the other. One by one they took us into another

room for questioning before they gave us their black and white stripes. There

were about eight guards with sticks in their hands in the second room, and

290 Freedom Riders

the Freedom Rider being questioned was surrounded by these men. Outside

we could hear the questions, and the thumps and whacks, and sometimes a

quick groan or cry when their questions weren’t answered to their satisfac-

tion. They beat several Riders who didn’t say ‘Yes, sir,’ but none of them

would Uncle-Tom the guards. Rev. C. T. Vivian . . . was beaten pretty bad.

When he came out he had blood streaming from his head.”

This was more than enough to convince Holloway, Harold Andrews

(Holloway’s classmate at Morehouse), and Peter Ackerberg, the white Free-

dom Rider from Antioch College, to post bond and accept a police escort to

the Jackson airport. However, nineteen of the Riders decided to stick it out,

to the obvious satisfaction of farm superintendent Max Thomas and his boss,

Sheriff J. R. Gilfoy. “We are not going to coddle them,” promised Gilfoy.

“When they go to work on the county roads this afternoon they are going to

work just like anyone else here.” The Freedom Riders would also wear “black

and white striped prison uniforms,” just like the other prisoners, though he

couldn’t resist pointing out that so far the regular inmates had refused to

“have anything to do with them.” This would not be the last time that a

Mississippi official would suggest that outside agitators were the lowest of

the low, deserving the contempt of even hardened criminals. Despite his

pledge to treat the Riders like the other prisoners, Gilfoy soon decided that

it was too risky to put them to work on the roads or in the fields, where they

might encounter meddling journalists. Instead he kept them confined to their

cells, which many of the Riders came to view as a greater hardship than any-

thing that might have awaited them beyond the bars.

28

In Montgomery, Monday morning brought excitement of a different

sort. Praising the Alabama National Guard for “restoring public confidence

in law and order” and proving to “the world that this state can and will con-

tinue to maintain law and order without the aid of Federal force,” John

Patterson announced that martial law in Montgomery would end at mid-

night. With most of the federal marshals already withdrawn, Patterson’s an-

nouncement seemed to signal a lessening of the tension between state and

federal authorities. But any notion that the Alabama phase of the crisis was

completely over was dispelled by the continuing hunger strike at the county

jail, where, to the dismay of their jailers, Abernathy and company had orga-

nized the Montgomery County Jail Council for the purpose of encouraging

other prisoners to sing freedom songs and “join in the spirit” of the move-

ment. Even more alarming was the legal drama unfolding in Judge Frank John-

son’s courtroom. On Wednesday, May 24, the Justice Department had filed a

request to expand the injunction against Alabama Klansmen and other vigi-

lantes to include local police officials in Birmingham and Montgomery, and

Judge Johnson had agreed to begin hearings on the matter on Monday. With

John Doar handling the government’s case and federal marshals standing

guard, and with L. B. Sullivan, Jamie Moore, Bull Connor, riot leader Claude

Henley, and Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton in the audience, the scene in

Johnson’s courtroom was one of the most dramatic in the city’s history.

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 291

The opening witness, a Tennessee State student named Patricia Jenkins,

identified Henley as one of the leading assailants during the May 20 riot and

testified that she had seen a policeman leave the scene as soon as the bus

arrived at the terminal. Other witnesses—including Fred Gach, FBI Special

Agent Spender Robb, and John McCloud, a black postal employee—confirmed

the general absence of police protection and the refusal of sheriff’s deputies

and other local authorities to intervene on behalf of reporters and Freedom

Riders under attack. Even more damning was the testimony of Stuart

Culpepper, a reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser, who testified that Jack

Shows, a local police detective, had told him before the riot began that the

police “would not lift a finger” to protect the Freedom Riders. By the time

the hearing recessed just after six o’clock, the government’s case for an ex-

panded injunction appeared to be a lock. but there were still more witnesses

waiting to testify, and Johnson had yet to hear from the defense. To the

dismay of those who had hoped to put the episode behind them, the hearing

would go on for three more days.

29

In Louisiana, the ultimate destination of the Freedom Rides, the scene

was only slightly less charged. On May 29 George Lincoln Rockwell was

spending his last day in jail before being released on bond, but the rest of the

Hate Bus contingent planned to remain behind bars and to continue a four-

day hunger strike. Across town, the four CORE Freedom Riders who had

posted bond on Saturday—Dennis, Smith, Aaron, and Castle—were busy

helping set up a Freedom Rider “school.” According to Rudy Lombard, the

president of New Orleans CORE, the school boasted two visiting instruc-

tors, CORE field secretary Jim McCain and Dr. Walter Bergman, one of the

victims of the May 14 riots in Alabama. The first class of ten students—

which included five white students from Cornell University in upstate New

York—began studying nonviolence on Monday morning, in preparation for

an upcoming trip to Jackson. Although Lombard would not disclose when

the group planned to leave for Mississippi, the announcement that the school

had opened put Louisiana law enforcement on full alert. The anxiety was so

high on Monday afternoon that New Orleans policemen began stopping any

vehicles carrying suspicious-looking passengers who might be Freedom Rid-

ers. One group caught in the dragnet turned out to be fifteen college-age

students (only one of whom was black) who had come to Louisiana to sell

magazine subscriptions. Police officials, who considered the city to be under

attack, made no apologies for their misplaced vigilance. In the wake of the

Alabama and Mississippi Freedom Rides, traveling in interracial groups had

become a suspicious activity all across the Deep South, regardless of the cir-

cumstances. No one was above suspicion, as popular rhythm-and-blues sing-

ers Clyde McPhatter and Sam Cooke had discovered earlier in the week when

their charter bus with a New York license plate pulled into Birmingham.

Misidentified as Freedom Riders by vigilant local whites, McPhatter, Cooke,

and several white backup musicians were forced to leave town in a hurry.

30

292 Freedom Riders

Racial tensions were also rising in Washington, where there was a lot of

tough talk on both sides of the Freedom Rider issue on the Monday following

the Mississippi arrests. While Senator Philip Hart of Michigan and other promi-

nent liberals continued to defend the Freedom Rides, the demise of the Javits

resolution endorsing the deployment of federal marshals encouraged a num-

ber of conservative senators and congressmen to unleash verbal assaults on

outside agitators. One militant segregationist, Senator Olin D. Johnston of

South Carolina, even sent a public letter to his constituents insisting that the

Freedom Riders “should be stopped in their tracks at the place of origin and

not allowed to prey upon the religious, racial, and social differences of our

people.” The biggest political story to come out of the nation’s capital on May

29, however, was Robert Kennedy’s decision to file a petition asking the Inter-

state Commerce Commission to adopt “stringent regulations” prohibiting seg-

regation in interstate bus travel. Citing the recent experiences of the Freedom

Riders, he declared that ICC action was needed to end the legal confusion that

had contributed to mob violence in the South.

Six years earlier the ICC had issued an order mandating the desegrega-

tion of interstate train travel, including terminal restaurants, waiting rooms,

and restrooms. The November 1955 order had also directed interstate bus

companies to discontinue the practice of segregating passengers, but said

nothing about segregated bus terminals. Even more confusing was the

commission’s subsequent decision to forego any real effort to enforce the

order. When the ICC won a judgment against Southern Stages, Inc. in

April 1961, it was the first instance of even token enforcement of bus de-

segregation. And even in the Southern Stages case, which involved the seg-

regation of a black interstate passenger in Georgia in the summer of 1960,

the hundred-dollar fines levied against the company and a driver represented

little more than a slap on the wrist. While a number of other cases were

pending, the ICC’s overall record of enforcement was, in the words of one

historian, “a sorry one,” thanks in part to the willingness of Justice Depart-

ment officials to look the other way.

In submitting a detailed, seven-section petition to the ICC, Kennedy

was attempting to end the confusion. He was also sending a clear signal that

his own department would no longer tolerate nonenforcement of the law.

Why he waited so long to do so is something of a mystery, but there is no

evidence that he thought much about the ICC’s potential role until the Free-

dom Ride Coordinating Committee called for the commission’s involvement

on May 26. As he surely knew, the ICC had enjoyed jurisdiction over inter-

state buses since the passage of the Motor Carrier Act of 1935, yet had done

next to nothing to combat discrimination; but he also knew that, as a newly

appointed attorney general still adjusting to the realities of bureaucratic life,

he had little hope of summarily countermanding decades of inaction and

neglect. Considering the ICC’s notorious reputation for political conserva-

tism and glacial deliberation, his lack of confidence was well founded, which

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 293

suggests that his decision to turn to the ICC on May 29 was more an act of

desperation than the result of a carefully rendered strategy.

When Kennedy first broached the subject with Burke Marshall and others

on Friday, there was no hint that he actually planned to follow through with a

formal appeal to the ICC. But on Monday morning, after a weekend of alarm-

ing reports about impending Freedom Rides and racial polarization, he could

think of nothing else, ordering his staff to produce a fully developed document

by the end of the day. The resulting “petition,” a novel form of appeal sug-

gested by Justice Department attorney Robert Saloscin, was a hodgepodge of

legal and legislative citations mixed with moral and political imperatives. Nev-

ertheless, the message to the lumbering ICC was clear. “Just as our Constitu-

tion is color blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens” the

petition advised, “so too is the Interstate Commerce Act. The time has come

for this commission, in administering that act, to declare unequivocally by regu-

lation that a Negro passenger is free to travel the length and breadth of this

country in the same manner as any other passenger.”

Kennedy’s enthusiasm for the egalitarian platitudes in the petition con-

firmed what many on his staff already knew: Despite his growing impatience

with the Freedom Riders’ confrontational tactics and his lack of experience

in civil rights matters, the attorney general was ideologically and emotionally

committed to racial equality. Even when concern for his brother’s vulner-

ability on the world stage pushed him to lash out at the Freedom Riders’

intransigence, he could not bring himself to abandon the basic principle of

equal justice. On Friday afternoon, while he was still fuming over the civil

rights community’s rejection of a cooling-off period, he delivered an appar-

ently unscripted Voice of America radio address that trumpeted the nation’s

commitment to equality. Speaking to an international audience spread across

sixty countries, he attempted to put the recent troubles in Alabama and Mis-

sissippi in the context of a nation that was trying to overcome the violent and

white supremacist excesses of a lawless minority. Most of his speech was a

predictable rejoinder to Communist insinuations that the mobs in Alabama

represented the interests and attitudes of a racially repressive capitalist re-

gime, but at times he went much farther down the freedom road than Cold

War rhetoric or political discretion dictated, even suggesting the possibility

that the American electorate would elect a black president before the end of

the century. Pointing out the contrast between his brother’s status as an Irish-

Catholic president and the anti-Irish discrimination that his grandfather had

faced in the early-twentieth century, he insisted that a similar transformation

would soon come to black America. Such talk was no substitute for action, as

several liberal commentators pointed out. In the politically and racially con-

strained atmosphere of May 1961, though, even a single moment of idealistic

indiscretion was newsworthy.

None of this, of course, proves or even suggests that idealism was the

driving force behind Kennedy’s decision to petition the ICC on May 29. On

294 Freedom Riders

the contrary, all available evidence indicates that he embraced the petition as

a pragmatic solution to a short-term political problem. Although he knew

that it would take weeks and even months to obtain a definitive ICC ruling

on the regulations themselves, he recognized the immediate symbolic value

of the petition. Having failed in his jawboning effort to convince the Free-

dom Riders to accept a cooling-off period, he hoped that the petition would

at least take some of the steam out of the movement. That it did not do so

was a profound disappointment for him and his staff, not to mention a clear

sign that, for all his good intentions, the attorney general did not yet under-

stand the depth of feeling that was driving young Americans, black and white,

onto the freedom buses.

31

THE RISING SPIRIT OF THE MOVEMENT was much in evidence on Tuesday morn-

ing as the first press accounts of the ICC petition vied with radio and televi-

sion reports of new activity among Freedom Riders and their supporters. In

Washington, more than a hundred pro–Freedom Rider demonstrators—most

of whom were college or high school students from New York and Philadel-

Members of the Washington Freedom Riders Committee display protest signs as

they depart Times Square in New York for Washington, D.C., where they plan to

picket the White House and demand federal intervention in the South, May 30,

1961. (Library of Congress)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 295

phia—marched back and forth in front of the White House to protest the

administration’s lukewarm support of the Riders. Carrying signs that read

“End Segregation, the Shame of Our Nation” and “Attention Robert

Kennedy—There’s Been a 95-Year Cooling-Off Period,” the picketers de-

nied reports that they were Communist sympathizers, although one spokes-

person acknowledged that the biracial group “was left of center by all

traditional political definitions.”

Similar suspicions greeted the first “graduates” of the New Orleans Free-

dom Rider school when they arrived at the Illinois Central railway station in

downtown Jackson later in the morning. The newest group of Freedom

Riders—the first to conduct tests at a railway terminal—included four white

male students from Cornell; Bob Heller, a white Tulane sophomore and CORE

member originally from Long Island; and three black students—Sandra Nixon

of Southern University in Baton Rouge, and Glenda Gaither and Jim Davis of

Claflin College in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Both Gaither, the younger

sister of CORE field secretary Tom Gaither, and Davis, her boyfriend and

future husband, were veterans of the South Carolina sit-in movement. An all-

conference football star and the son of a prominent Methodist preacher, the

towering Davis served as the group leader during the May 30 Freedom Ride.

On the Ride itself, Davis and the others were pleased to discover that

seating on the train was fully integrated. It was a different story, however,

when he, Nixon, and Gaither tried to use the white restrooms at the Illinois

Central terminal. Once again police captain Ray was on the scene. After dis-

obeying his order to “move on,” the three restroom invaders—along with

the rest of the Riders—were arrested for disorderly conduct. Within an hour

all eight found themselves in front of a noticeably irritated Judge Spencer,

who, after a five-minute trial, meted out the expected sentence of a two-

hundred-dollar fine and a sixty-day jail term. By midafternoon the five whites

were in the city jail and the rest were in the county jail, which was already

crowded with the fifteen black Riders convicted on Monday as well as most

of the first batch of Riders convicted on Friday. On Monday evening, after

reporters, federal officials, and CORE field secretary Richard Haley had be-

gun to inquire about Vivian’s beating by county penal farm guards, Sheriff

Gilfoy had moved Vivian and most of the other Riders back to the county

jail. As a result, the conditions at the jail were declining by the hour.

By Tuesday evening—with the exception of eight white Riders incarcer-

ated in the city jail—the first five groups were all packed into a county jail

that was Spartan even by Mississippi standards. Even without the overcrowd-

ing the county jail was a miserable place, as Frank Holloway’s experience

earlier in the week had demonstrated. “When we went in,” Holloway re-

called, “we were met by some of the meanest looking, tobacco-chewing law-

men I have ever seen. They ordered us around like a bunch of dogs, and I

really began to feel like I was in a Mississippi jail. Our cell was nasty and the

beds were harder than the city jail beds, hardly sleepable, but the eight of us