Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

106 Freedom Riders

and Lafayette that he was alerting the Klan. No Klansmen actually appeared,

but when the two friends parted company later that night in Troy, they

nervously joked that they might not see each other again. For Lafayette, who

still had five hundred miles to travel before reaching his home in Tampa, the

situation seemed especially dangerous. In the end, both students arrived home

safely, suffering no more than the broken suitcase and the driver’s scowls in

the process. The whole experience filled them with a strange mixture of ex-

hilaration and outrage, and after their return to Nashville a discussion of

their narrow escape led to the idea of a second and more ambitious ride.

For more than a year they let the idea simmer, but in March 1961 they

sent a letter to the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, Birmingham’s leading civil

rights activist, proposing a test of both the Morgan and Boynton decisions. As

Lewis recalled many years later, “Our idea was to have a core group of us ride

the bus down to Birmingham and test the waiting areas, rest rooms and eat-

ing facilities in the Greyhound station there—perhaps the most rigidly seg-

regated bus terminal in the South—applying the same tactics we’d used with

our sit-ins and stand-ins in Nashville.” Though appreciative of their bravery,

Shuttlesworth urged the Nashville insurgents to find some other way to serve

the cause. Birmingham, he warned, was a racial powder keg that would ex-

plode if local white supremacists were unduly provoked, especially by outsid-

ers. This was not what Lewis and Lafayette wanted to hear, but their

disappointment turned to vindication a few days later when they discovered

CORE’s plan for a Freedom Ride. Lafayette, like Lewis, was determined to

join the Ride, but he was not yet twenty-one and needed his parents’ permis-

sion. Already exercised over her son’s role in the Nashville sit-ins, Lafayette’s

mother refused to sign the permission form, reminding him that she had

sent him “to Nashville to study, not to aggravate white folks.” Lafayette’s

father, an itinerant carpenter who had spent most of his life in the tough

Ybor City section of Tampa, was even more emphatic, thundering: “Boy,

you’re asking me to sign your death warrant.” Three weeks later young

Lafayette would ignore his parents’ wishes and join an NCLC-sponsored

Freedom Ride that would land him in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison. But at

this point the best he could do was to accompany Lewis and Bevel on a wild

car ride to Murfreesboro, where Lewis—who had missed his connection in

Nashville—caught the morning bus to Washington.

18

Lewis arrived in Washington on the morning of April 30, just in time to

join the other Freedom Riders for three days of intensive preparation and

training in nonviolence. All thirteen Riders stayed at Fellowship House, a

well-known Quaker meetinghouse and dormitory on L Street that had served

generations of pacifists and social activists. “Inside was room after room filled

with books and posters and pieces of art,” Lewis later recalled, “all centered

around the themes of peace and community.” To many of the Riders, such a

scene was familiar, but the young Alabamian “had never been in a building

like this,” nor “among people like this.” In this enclave of interracial brother-

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 107

hood, the beloved community that Lawson had conjured up suddenly seemed

less abstract and more achievable, at least until Farmer’s rather heavy-handed

welcoming speech complicated this ethereal vision.

In greeting his fellow Riders, Farmer made it clear that he was in charge

and that the Freedom Ride was first and foremost a CORE project. Anyone

unwilling to abide by CORE’s strict adherence to nonviolence should with-

draw from the project, he informed them in his best stentorian voice. He then

went on to outline the proposed Ride, providing “an overview of what we were

going to do, how we were going to do it, and the most optimistic and pessimis-

tic outcomes possible.” After several minutes of sobering orientation, he turned

the podium over to Carl Rachlin, a forty-two-year-old New York labor and

civil rights lawyer who served as CORE’s general counsel. Rachlin gave the

Riders a short course in constitutional law, focusing on federal and state laws

pertaining to discrimination in interstate transportation, and told them what

to do if and when they were arrested. Two additional speakers, a sociologist

and an experienced social activist, briefed the Riders on what to expect from

the white South. The sociologist, Farmer later recalled, “elaborated on the

mores and folkways of the areas through which we would be riding and de-

scribed the lengths to which the local populace probably would go to force

compliance with their sacrosanct racial customs,” and the activist followed with

a description of “what really was going to happen to us, including clobberings

and possibly death.” In the discussions that followed, several of the Riders shared

personal stories about the dangers of nonviolent protest and their experiences

with Jim Crow, and later in the day they were all encouraged to read and re-

read classic texts by Gandhi, Thoreau, and other celebrated exponents of non-

violence and civil disobedience.

19

All of this was a prelude to what CORE leaders considered to be the

most important part of the Riders’ training: “intense role-playing sessions”

designed to give them a sense of what they were about to face. Coordinated

by Carey, the sessions were carefully constructed “sociodramas—with some

of the group playing the part of Freedom Riders sitting at simulated lunch

counters or sitting on the front-seats of a make-believe bus. Others acted out

the roles of functionaries, adversaries, or observers. Several played the role

of white hoodlums coming to beat up the Freedom Riders on the buses or at

lunch counters at the terminals.” The sessions, which at times became “all

too realistic,” according to Farmer, went on for three grueling days, as the

participants swapped and reswapped places. After each session they evalu-

ated the role players’ actions and reactions, and over the course of the train-

ing each Rider got the chance to experience the full range of emotions and

crises that were likely to emerge during the coming journey. “It was quite an

experience,” Ben Cox recalled. “We were knocked on the floor, we poured

Coca-Cola and coffee on each other, and there was shoving and calling each

other all kinds of racial epithets, and even spitting on each other, which would

inflame you to see if you could stand what was going to come.” As a veteran

108 Freedom Riders

of Lawson’s Nashville workshop, Lewis had already undergone this kind of

training, but for most of the Riders the sessions represented a new and some-

what disconcerting ordeal. For John Moody, suffering from the flu and al-

ready unnerved by images of Southern violence, the training was intense

enough to prompt withdrawal from the Ride. And he was not the only recruit

to have second thoughts about subjecting himself to such abuse.

20

By the afternoon of May 3, the day before their scheduled departure, all

of the Riders were emotionally drained. During the final hours of prepara-

tion, as pride and anticipation mingled with fear and apprehension, Farmer

realized that he had to do something to break the tension. Following a few

freedom songs from Jimmy McDonald, he took the Riders downtown for an

elaborate Chinese dinner at the Yen Ching Palace, an upscale Connecticut

Avenue restaurant managed by NAG activist Paul Dietrich. The owner of

the restaurant, Van Lung, a close friend of Dietrich’s since their childhood

in upstate New York, was also a longtime associate of General Claire Lee

Chennault, the famed Louisiana-born leader of the World War II “Flying

Tigers” Asian fighter squadron. Prior to his death in 1958, Chennault had

been a frequent visitor to the Yen Ching Palace, and for several years, at the

close of duck-hunting season, the restaurant had hosted the Louisiana con-

gressional delegation’s annual Peking duck banquet. None of the Louisiana

politicos was present when the Freedom Riders filed into the restaurant on

the evening of May 3, but the dinner episode was exotic nonetheless. Many

of the younger Riders, including John Lewis, had never eaten Chinese food

before, and the whole scene somehow seemed appropriate for men and women

about to explore the unknown. “As we passed around the bright silver con-

tainers of food,” Lewis recalled, “someone joked that we should eat well and

enjoy because this might be our Last Supper.” This gallows humor seemed

to break the ice, and the gathering settled into a mood of genuine fellowship.

By the time the steamed rice and stir-fried vegetables gave way to fortune

cookies, it was clear that the experiences of the last three days had created a

family-like bond among the Riders.

As the cookies and pots of tea were making their way around the table,

Dietrich and several other NAG activists joined the group, just in time to

hear a soul-searching speech by Farmer. Obviously pleased with what had

transpired since the Riders had arrived in Washington, he wanted them to

know that he had faith in their ability to meet any challenge, but he went on

to insist that he was the only “one obligated to go on this trip,” that “there

was still time for any person to decide not to go.” If one or more of them

chose not to go, “there would be no recrimination, no blame, and CORE

would pay transportation back home.” After Farmer closed his remarks and

settled back into his chair, Cox offered to lead the Riders in prayer. Farmer,

in deference to the atheists and agnostics present, suggested that a moment

of silence was more appropriate. The “moment” went on for a full five min-

utes as the Riders mulled over the CORE leader’s offer. Finally, he broke the

silence by telling them that they did not have to make an immediate decision;

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 109

they could tell him “later that night or just not show up at the bus terminal in

the morning, whichever was easiest.” With this unsettling benediction, the

Riders filed out of the restaurant in near silence. Back at Fellowship House,

a few nervous conversations ensued, but most chose to wrestle with their

consciences individually and in private. Although the long-awaited Freedom

Ride was scheduled to leave in a few hours, no one knew how many Riders

would actually appear at the bus station in the morning.

Farmer’s escape clause reminded the Riders of the gravity of the situa-

tion. Most were well aware of the dangers ahead, and earlier in the week each

would-be Rider had signed a waiver releasing CORE from any liability for

injuries suffered during the Ride, but Farmer’s final warning virtually guar-

anteed a night of wide-eyed restlessness. Some of the Riders made last-minute

calls to friends and family before retiring. Others stayed up late completing

their wills or just jotting down their thoughts and reflections. A few never

went to bed at all. There was so much to think about, and even among the

most hardened veterans of the struggle so many unknowns to contemplate,

so many mysteries of the human condition to ponder.

Farmer received several calls that evening, including one from his old

boss Roy Wilkins, who asked, somewhat facetiously, if CORE was actually

going to go through with its “joy ride.” Farmer was not amused, but, know-

ing that the Riders might need the NAACP in the days ahead, he bit his

tongue. He assured Wilkins that everything was set, though in truth he was

beginning to have his doubts. During the long, hard night before the depar-

ture, as he replayed the evening’s events in his mind, he began to worry that

he had unwittingly sown the seeds of failure with his offer to let the volun-

teers back out. He was not one to wallow in self-doubt, but this time he could

not help but second-guess himself. Why hadn’t he left well enough alone?

Had he come this far only to see his dream dissolve in a torrent of needless

panic fostered by his own well-meaning but careless words? What would

happen to CORE and the movement if word got out, as it surely would, that

the Freedom Riders had lost their nerve? These questions haunted him as he

awoke on the most important morning of his life.

Only when Farmer arrived at the breakfast table and saw the determina-

tion in the eyes of his fellow Riders did he realize that his fears were un-

founded. “They were prepared for anything, even death,” he later insisted.

No one had withdrawn, and individually and collectively they appeared ready

to do what had to be done, not in a spirit of selfless or reckless heroism but as

a vanguard of ordinary citizens seeking simple justice. The time had come to

challenge the hypocrisy and complacency of a nation that refused to enforce

its own laws and somehow failed to acknowledge the utter indecency of racial

discrimination.

21

THE SCENE AT THE DOWNTOWN TRAILWAYS AND GREYHOUND STATIONS that

morning gave little indication that something momentous was about to

unfold. There were no identifying banners, no protest signs—nothing to

110 Freedom Riders

signify the start of a revolution other than a few well-wishers representing

CORE, NAG, and SCLC. Despite a spate of CORE press releases, the be-

ginning of the Freedom Ride drew only token coverage. No television cam-

eras or radio microphones were on hand to record the event, and the only

members of the national press corps covering the departure were an Associ-

ated Press correspondent and two local reporters from the Washington Post

and the Washington Evening Star.

The only other journalists present were three brave individuals who had

agreed to accompany the Riders to New Orleans: Charlotte Devree, a fifty-

year-old white freelance writer and CORE activist from New York who hoped

to publish a firsthand account of the Freedom Ride (and who frequently would

be misidentified as a Freedom Rider); Simeon Booker, a forty-three-year-

old black feature writer originally from Baltimore representing Johnson Pub-

lications’ Jet and Ebony magazines; and Ted Gaffney, a thirty-three-year-old

Washington-based photographer and Johnson stringer. A fourth journalist,

Moses Newson, the thirty-four-year-old city editor of the Baltimore Afro-

American, would later join the Ride in Greensboro, North Carolina. All four

were seasoned journalists, especially Booker, a former Nieman Fellow who

had attracted considerable attention for his riveting coverage of the sensa-

tional 1955 Emmett Till murder case. But only Newson—a native of Lees-

burg, Florida, who had worked for the Memphis Tri-State Defender in the

early 1950s and who had covered both the 1956 Clinton, Tennessee, and

1957 Little Rock, Arkansas, school desegregation crises—had extended ex-

perience in the Deep South. Gaffney had relevant experience of a different

kind, however. In June 1946, as a young soldier traveling by bus from Wash-

ington to Fort Eustis, Virginia, he had conducted a personal test of the re-

cent Morgan decision. Although the driver “turned red and trembled with

rage,” Gaffney ignored the order to move to the back of the bus and rode all

the way to Fort Eustis on a front seat. Fifteen years later memories of this

“first freedom ride” came flooding back as he boarded the bus that would

take him on the ride of his life.

Two weeks earlier the CORE office had sent letters describing the im-

pending Freedom Ride to President Kennedy, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover,

Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the chairman of the ICC, and the presi-

dents of Trailways and Greyhound. But no one had responded, and as the

Riders prepared to board the buses there was no sign of official surveillance

or concern. At Farmer’s request, Simeon Booker, who was known to have

several close contacts in the Washington bureaucracy, called the FBI to re-

mind the agency that the Freedom Ride was about to begin, and on the eve

of the Ride Booker had a brief meeting at the Justice Department with At-

torney General Kennedy and his assistant John Seigenthaler. Booker warned

Kennedy that the Riders might need protection from segregationist thugs,

but the young attorney general did not seem to appreciate the gravity of the

situation. After telling the black journalist to “call” him if trouble arose,

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 111

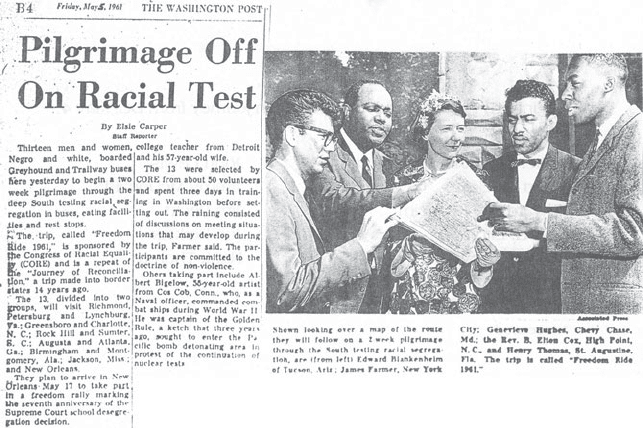

Written by staff reporter Elsie Carper, this article on the CORE

Freedom Ride appeared on page B4 of the Washington Post,

May 5, 1961. (Courtesy of the Washington Post)

Kennedy quipped: “I wish I could go with you.” All of this left Booker won-

dering if Kennedy had been paying full attention to their conversation, a

suspicion confirmed when the attorney general later claimed that he had been

blindsided by the Freedom Ride.

Once all of the Freedom Riders had arrived at the bus stations, Farmer

held a brief press conference, during which he tried to explain both the phi-

losophy of nonviolence and CORE’s “jail–no bail” policy. “If there is an ar-

rest, we will accept that arrest,” he told the handful of reporters, “and if there

is violence we will accept that violence without responding in kind.” Accept-

ing bail was contrary to the spirit of noncooperation with evil, he added:

“We will not pay fines because we feel that by paying money to a segregated

state we would help it perpetuate segregation.” Leaving the reporters to puzzle

over the implications of this declaration, he turned to the Riders themselves,

whom he divided into two interracial groups. Six Riders lined up at the Grey-

hound ticket counter, and the other seven did the same at the Trailways

station across the street.

After checking their bags, the Riders received last-minute instructions

about seating arrangements. A proper test of the Morgan decision required a

careful seating plan, and Farmer left nothing to chance. Each group made

sure that one black Freedom Rider sat in a seat normally reserved for whites,

that at least one interracial pair of Riders sat in adjoining seats, and that the

remaining Riders scattered throughout the bus. One Rider on each bus served

as a designated observer and as such remained aloof from the other Riders;

by obeying the conventions of segregated travel, he or she ensured that at

112 Freedom Riders

least one Rider would avoid ar-

rest and be in a position to con-

tact CORE officials or arrange

bail money for those arrested.

Most of the Riders, however,

were free to mingle with the

other passengers and to discuss

the purpose of the Freedom

Ride with anyone who would

listen. Exercising the constitu-

tional right to sit anywhere on

the bus had educational as well as legal implications, and the Riders were

encouraged to think of themselves as teachers and role models. Farmer im-

posed a strict dress code—coats and ties for the men and dresses and high

heels for the women—and all of the Riders were asked to represent the cause

of social justice openly and honestly without resorting to needlessly provoca-

tive or confrontational behavior. As Farmer reminded them just before the

buses pulled out, they could be arrested at any time, so they had to be pre-

pared for the unexpected. Accordingly, he urged each Rider to bring a carry-

on bag containing a toothbrush, toothpaste, and an inspiring book or two

that would help fill the hours behind bars. Many years later, Lewis remem-

bered packing three books in the bag that he placed under his seat: one by

the Roman Catholic philosopher Thomas Merton, a second on Gandhi, and

the Bible.

22

All of these precautions and warnings took on new meaning as the buses

actually headed south on Route 1. At first the regular passengers, both black

and white, paid little attention to the Freedom Riders. No one, including the

drivers, voiced any objection to the Riders’ unusual seating pattern. This was

encouraging and somewhat unexpected, but the first true test of tolerance

did not come until the Greyhound stopped at Fredericksburg, fifty miles

south of Washington. A small river town with a rich Confederate heritage

and the site of one of the Union Army’s most crushing defeats, Fredericksburg

had a long tradition of strict adherence to racial segregation and white su-

premacy. Gaither’s scouting report had warned the Riders that the facilities

at Fredericksburg’s bus terminals featured the all too familiar

WHITE ONLY

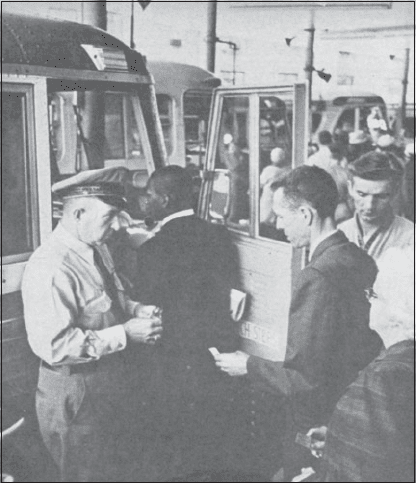

CORE Freedom Riders (left to

right) Charles Person, Jim Peck,

and Frances Bergman board a

southbound Trailways bus in

Washington, D.C., May 4,

1961. (Photograph by Theodore

Gaffney)

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 113

114 Freedom Riders

and

COLORED ONLY signs. When they arrived at the Greyhound terminal, the

Jim Crow signs were prominently displayed above the restroom doors. Nev-

ertheless, someone in a position of authority had decided that there would be

no trouble in Fredericksburg on May 4. Peck used the colored restroom, and

Person, the designated black tester for the day, used the white restroom and

later ordered a drink at the previously whites-only lunch counter, all without

incident. To the Riders’ surprise, the service was cordial, and not a harsh

word was spoken by anyone. This apparent lack of rancor in the state that

had spawned the “massive resistance” movement only a few years earlier was

almost eerie, and as the Riders reboarded the bus, they couldn’t help won-

dering what other surprises lay ahead.

23

The next stop was Richmond, where the Riders were scheduled to spend

the night at Virginia Union College, a black Baptist institution located a few

blocks north of the city’s downtown business district. Understandably wary

of a city that had served as the capital of the Confederacy for four years, they

did not expect a warm welcome, especially after Farmer informed them that

local NAACP leaders had urged their followers to avoid any association with

the Freedom Ride. Even so, the fear that local whites would try to prevent

them from desegregating the city’s bus terminals proved unfounded. As Lewis

later recalled, the Riders encountered “No signs. No trouble. Nothing but a

few cold stares.” There were, however, a few disheartening moments, at least

for Peck. As he wandered through the Greyhound terminal—the same ter-

minal that he had visited fourteen years earlier—he realized that the absence

of Jim Crow signs had not led to any apparent changes in behavior. Unaware

of or unmoved by the Boynton decision, “Negroes were sticking to the for-

merly separate and grossly unequal colored waiting rooms and restaurants.”

The same was true at the nearby Trailways station, where traditional pat-

terns of separation and deference still prevailed. Such scenes were profoundly

discouraging to a man who had devoted his entire adult life to the struggle

for racial equality. Peck knew that, as a white man and a Northerner, he had

no right to pass judgment on the frailties of black Southerners. Later that

evening, however, as he sat through a sparsely attended meeting at the Vir-

ginia Union chapel, he felt a twinge of sadness, not only for the blacks still

ensnared in the indignities of Jim Crow but also for the Freedom Riders who

were taking such grave risks for a potentially empty victory. After interview-

ing several apathetic Virginia Union students, the New York writer Char-

lotte Devree shared some of Peck’s concerns. But a late-night conversation

with Charles Sherrod, a campus hero from Petersburg who had just gained

his release from the Rock Hill jail, restored some of her faith in the black

student movement. Speaking with a “cold fury” that stunned Devree, Sherrod

insisted: “Some of us have to be willing to die.”

24

Sherrod’s words were enough to give anyone pause, especially a New

Yorker facing her first visit to the Deep South. But when it came time to

board the bus for the second day of the Freedom Ride, Devree overcame her

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 115

fears and headed south with the rest of the group, realizing full well that the

Freedom Riders, like Sherrod, were prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice

for the cause of freedom. Fortunately, no such sacrifice was expected any

time soon. Still in the Upper South, the Riders did not foresee much resis-

tance in towns like Petersburg, where they disembarked for an overnight

stay on May 5. Only twenty miles south of Richmond, Petersburg was a rough-

and-tumble railroad town that had witnessed more than its share of carnage

during the Civil War, including the final collapse of Robert E. Lee’s army.

In the modern era the town had evolved into an important processing center

for the tobacco and peanut farmers of the Virginia Southside. Over 40 per-

cent black and the home of Virginia State University, Petersburg, like many

lowcountry Virginia communities, practiced an ambiguous mix of hard-

edged segregation and paternalistic pretense. As Gaither’s scouting report

had promised, despite recent tensions the town had seen relatively few mani-

festations of ultra-segregationist extremism. On the contrary, it had become

a major center of movement activity and one of the few communities in the

South where sit-ins had already led to desegregated bus terminals. In August

1960, after the Petersburg Improvement Association (PIA) sponsored a se-

ries of sit-ins at the local Trailways terminal, the president of Bus Terminal

Restaurants agreed to desegregate lunch counters in Petersburg and several

other cities. Thus, when the Freedom Riders arrived in the city nine months

later, the successful testing of local facilities was almost a foregone conclusion.

As expected, the testing went off without incident, and the Riders received an

enthusiastic welcome from a crowd that included some of the fifty-five sit-in

veterans arrested at the Trailways terminal the previous summer.

Ironically, the one Petersburg civil rights activist who was not there to

greet them was the Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker, the strong-willed thirty-

one-year-old Baptist minister who had led the PIA since its founding. Hav-

ing replaced Ella Baker as executive secretary of SCLC the previous spring,

Walker was in Atlanta, where he and other SCLC leaders would meet with

the Riders on May 13. A native of New Jersey who as a teenager had joined

the Communist Party after attending a lecture by Paul Robeson, Walker was

one of the movement’s most flamboyant characters. After attending Virginia

Union and moving to Petersburg in 1953 to become pastor of Gillfield Bap-

tist Church, he became active in the NAACP and eventually came under the

influence of Vernon Johns, the legendary black preacher who preceded Mar-

tin Luther King Jr. as pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

With Johns’s blessing, Walker caused quite a stir in 1958 when he and sev-

eral others tried to desegregate the Petersburg Public Library—a protest

that included a cheeky attempt to check out Douglas Southall Freeman’s ad-

miring biography of Robert E. Lee. This and other acts of defiance drew the

admiring attention of King, who both encouraged the formation of the PIA

and eventually invited Walker into SCLC’s inner circle. At the same time,

Walker developed a working relationship with CORE, first as the coordinator