Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

86 Freedom Riders

This spirit of independence became manifest when nearly two hundred

student activists—including 126 black students representing fifty-six colleges

and high schools across the South—met at Shaw University in Raleigh in

mid-April. The Raleigh conference was the brainchild of fifty-six-year-old

Ella Baker, who after years of false starts and dashed hopes had grown disen-

chanted with the cautious policies of SCLC and the NAACP. Representa-

tives of all the major civil rights organizations were present, but Baker made

sure that the students themselves ran the show. Though still an employee of

SCLC, she urged the student activists to plot their own course and to avoid

the controlling influence of any existing organization. Just before the open-

ing of the Raleigh meeting, King issued a lengthy press-conference state-

ment outlining a proposed strategy for the student movement. But the speaker

who aroused the most interest among the delegates was Jim Lawson, re-

cently expelled from Vanderbilt University’s School of Divinity for his lead-

ership role in the Nashville sit-ins.

Born in western Pennsylvania in 1931 and raised in Massillon, Ohio,

Lawson was an articulate and sophisticated student of Gandhian philosophy

who had already served a year in prison as a conscientious objector during

the Korean War and three years as a Methodist missionary in India. After

meeting King at Oberlin College in 1956, Lawson took the Montgomery

minister’s advice to postpone his divinity studies and head south to spread

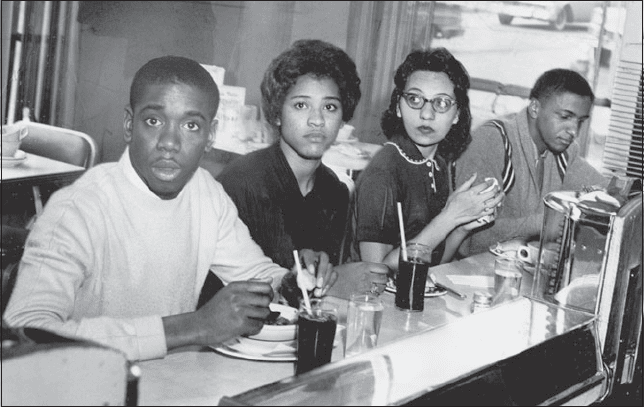

Following a series of sit-ins, four student activists become the first blacks to eat

lunch at the Post House Restaurant in the Nashville, Tennessee, Greyhound

terminal, May 16, 1960. The Post House was the first downtown lunch counter

in Nashville to be desegregated. From left to right: Matthew Walker Jr., Peggy

Alexander, Diane Nash, and Stanley Hemphill. Walker and Nash became

Freedom Riders in 1961. (Courtesy of the Nashville Tennessean)

Beside the Weary Road 87

the word about nonviolence. Subsequent conversations with A. J. Muste and

Glenn Smiley, whom he had known for years, led to his appointment as FOR’s

Southern field secretary. At Smiley’s suggestion, he soon moved to Nash-

ville, Tennessee, where he helped organize the Nashville Christian Leader-

ship Conference and where his nonviolent workshops eventually attracted a

dedicated following of young disciples, including John Lewis, Diane Nash,

Bernard Lafayette, and others who would later gain prominence as Freedom

Riders. Grounded in a mixture of social-gospel Methodism and insurgent

Gandhianism, Lawson’s intellectual and moral leadership gave the local Nash-

ville movement a strength of purpose that no other student group could match.

With the blessing of the Nashville Christian Leadership Council (NCLC)

president Kelly Miller Smith, Lawson’s increasingly restless disciples had

recently formed a Student Central Committee to mediate the relationship

between local student activists and the older and generally more cautious

ministers of the NCLC. Together, the students and the NCLC constituted

a powerful if sometimes uneasy tandem that made the Nashville Movement

the most effective local direct action organization since the early Montgomery

Improvement Association. Speaking at Fisk University in the immediate after-

math of the Raleigh conference, an admiring King called the Nashville Move-

ment “the best organized and most disciplined in the Southland,” a judgment

later confirmed by Nashville’s critical role in the Freedom Rides.

In Raleigh, Lawson and the Nashville delegation dazzled King and many

of the student activists with concrete visions of social justice and the “be-

loved community.” To some, Lawson’s sermon-like keynote speech seemed

long on religion and a bit short on practical politics, but even the most secu-

lar delegates applauded when he warned established movement leaders that

the sit-ins represented a “judgment upon middle-class conventional, half-

way efforts to deal with radical social evil.” In an obvious slap at the NAACP,

he insisted that the civil rights struggle could no longer tolerate a narrow

reliance on “fund-raising and court action.” Instead, it had to cultivate “our

greatest resource, a people no longer the victims of racial evil who can act in

a disciplined manner to implement the constitution.” Baker later echoed these

words in a stirring speech that called for a broad assertion of civil rights,

rights that involved “more than a hamburger,” as she put it. All of this in-

spired the young delegates to take themselves seriously, and on the second

day of the conference they voted to form an independent organization known

as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Marion Barry,

a twenty-two-year-old Fisk University chemistry graduate student and fu-

ture mayor of Washington, D.C., won election as SNCC’s first chairman,

solidifying the Nashville group’s influence.

44

In May, SNCC reaffirmed its independence at an organizational meeting

held in Atlanta, but at this point the student organization constituted little

more than a “clearinghouse for the exchange of information about localized

88 Freedom Riders

protests.” With no permanent staff and no financial backing to speak of, SNCC

leaders had little choice but to draw upon the resources of older organiza-

tions such as SCLC, which allowed them to establish a small office at SCLC

headquarters. The national leadership of the NAACP, despite serious mis-

givings about the sit-in movement, provided SNCC activists with free legal

representation and even hired the Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox, an outspo-

ken, courageous black minister and future Freedom Rider from High Point,

North Carolina, to serve as a roving ambassador of nonviolence. Paralleling

the efforts of CORE field secretaries Carey and McCain, Cox traveled across

the South during the spring and summer of 1960, spreading the gospel of

nonviolence to as many students as possible. Most student activists were re-

ceptive to the nonviolent message, if only for pragmatic reasons, and despite

numerous provocations by angry white supremacists, the sit-ins proceeded

without unleashing the violent race war that some observers had predicted.

At the same time, however, the students were unwilling to sacrifice the intel-

lectual and organizational independence of their movement, even when con-

fronted with elders who invoked religious, moral, or paternal authority. All

of this led historian and activist Howard Zinn to marvel that “for the first

time in our history, a major social movement, shaking the nation to its bone,

is being led by youngsters.”

45

CORE’s failure to absorb the student movement was a disappointment,

but the organization took pride in the fact that a number of the movement’s

most committed activists gravitated toward CORE’s demanding brand of

nonviolence. In Tallahassee, Florida A&M coed Pat Stephens and seven other

young CORE volunteers became the first sit-in demonstrators of their era to

acknowledge the importance of “unmerited suffering.” By refusing to accept

bail and remaining behind bars for sixty days in the spring of 1960, they

introduced a new tactic known as the “jail-in.” In an eloquent statement com-

posed in her cell, Stephens reminded her fellow activists of Martin Luther

King’s admonition that “we’ve got to fill the jails in order to win our equal

rights.” At the time, it was standard practice for arrested demonstrators to

seek an early release from jail. Most demonstrators, as well as most move-

ment leaders, agreed with Thurgood Marshall, who insisted that only a fool

would refuse to be bailed out from a Southern jail. “Once you’ve been ar-

rested,” he told a crowd at Fisk on April 6, 1960, “you’ve made your point. If

someone offers to get you out, man, get out.”

46

Convincing arrested demonstrators to ignore such advice soon became a

cornerstone of CORE policy, and one of the activists most responsible for

this new emphasis was Tom Gaither, another rising star among CORE re-

cruits. When he first met McCain in March 1960, Gaither was a biology

major and student leader at all-black Claflin College in Orangeburg, South

Carolina. Following a mass protest in Orangeburg, he was one of more than

350 students “arrested and herded into an open-air stockade.” This was the

largest number of demonstrators arrested in any Southern city up to that

Beside the Weary Road 89

point, and McCain couldn’t help being impressed with the courage of the

Orangeburg students. Gaither’s leadership in the face of tear gas and fire hoses

prompted CORE to offer him a staff position, and by September he found

himself in the midst of a major sit-in campaign in Rock Hill. Working closely

with McCain and student leaders at Friendship Junior College, he helped to

turn Rock Hill into one of the movement’s most militant battlegrounds. In

February 1961 Rock Hill became the site of the movement’s first widely pub-

licized “jail-in.” A month later, following his release from a county road gang,

Gaither agreed to serve as an advance scout for a new CORE project known as

the Freedom Ride—a fitting assignment for someone who had been one of the

first to promote the idea of such a ride earlier in the year.

47

The youthful dynamism of Stephens, Gaither, and other recruits helped

to revitalize CORE, which was brimming with optimism by the summer of

1960. At the national CORE convention in July, Carey—recently promoted

to the position of field director—claimed that the organization was on the

verge of becoming “a major race relations group.” In August CORE’s ex-

panding staff gathered in Miami for a second “interracial action institute,”

during which they experimented with the tactic of “jail–no bail.” Following a

sit-in at a Miami lunch counter, seven participants, including Gaither,

Stephens, executive director Jimmy Robinson, and future Freedom Rider

Bernard Lafayette, spent ten days in jail. Such actions enhanced CORE’s

reputation for militance and boosted expectations of increased activity. By

September CORE’s field staff had grown to five “field secretaries”: McCain;

Gaither; Joe Perkins, a black graduate student at the University of Michigan;

Richard Haley, a Chicago-born black Tallahassee activist and former music

professor at Florida A&M; and Genevieve Hughes, a twenty-eight-year-old

white stockbroker who had spearheaded the New York City chapter’s dime-

store boycott.

48

In October 1960 the CORE field staff fanned out across the South look-

ing for new centers of struggle. What they found—especially in New Or-

leans, where a committed band of activists was engaged in an all-out assault

on Jim Crow, and in South Carolina, where more and more students were

responding to McCain and Gaither’s organizing efforts—demonstrated that

the spirit of nonviolent resistance was still on the rise. But, at the time, none

of CORE’s advances into the Southern hinterland drew much attention. In

the movement at large, all eyes were on Atlanta. Part of the excitement was

the reorganization of SNCC, which, during a fateful meeting at Atlanta Uni-

versity, moved toward a more secular orientation that placed “a greater em-

phasis on political issues.” The influence of Lawson and the Nashville

Movement on SNCC was declining, and Orangeburg sit-in veteran Chuck

McDew, a black Ohioan who had converted to Judaism, soon replaced Marion

Barry as SNCC chairman. The biggest news, however, was the arrest and

imprisonment of Martin Luther King following a sit-in at Rich’s department

store on October 19.

90 Freedom Riders

The first of eighty demonstrators to be arraigned, King refused Judge

James Webb’s offer to release him on a five-hundred-dollar bond. “I cannot

accept bond,” the SCLC leader proclaimed. “I will stay in jail one year, or

ten years.” This was the kind of courageous leadership that the militants of

SNCC and CORE had been advocating, but they got more than they had

bargained for when Georgia authorities dropped the charges against all of

the defendants but King. The apparent singling out of the nation’s most

celebrated civil rights leader raised doubts about his safety, a concern that

turned into near panic after he was moved from the relative security of his

Atlanta jail cell, first to the DeKalb County Jail and later to the maximum

security prison at Reidsville. Fearing that King’s life was in danger, SCLC

and other movement leaders urged the Justice Department to intervene but

got no response—a development that set the stage for one of the most fateful

decisions in modern American political history.

49

Harris Wofford, a liberal campaign aide to Democratic presidential can-

didate John Kennedy, had known King since 1957 and had even raised funds

for the SCLC leader’s trip to India, where Wofford had spent several years

studying Gandhian philosophy. Frustrated by Kennedy’s reluctance to take a

forthright stand on civil rights, he sensed that King’s endangerment pro-

vided his candidate with a golden opportunity to make up for past mistakes.

After receiving a phone call from an obviously desperate Coretta King,

Wofford made the political and ethical case for an expression of sympathy.

“If the Senator would only call Mrs. King and wish her well,” he told his boss

Sargent Shriver, “it would reverberate all through the Negro community in

the United States. All he’s got to do is say he’s thinking about her and he

hopes everything will be all right. All he’s got to do is show a little heart.”

While campaigning with Kennedy in Chicago, Shriver relayed Wofford’s

suggestion, which, to the surprise of the entire campaign staff, led to an im-

pulsive late-night phone call. Startled and touched by Kennedy’s expression

of concern, Mrs. King later made it clear to the press that she appreciated

the senator’s gesture, which stood out in stark contrast with Vice President

Richard Nixon’s refusal to comment on her husband’s situation.

Nixon’s inaction widened the opening for the Kennedy campaign, al-

lowing the Democratic candidate’s younger brother Bobby to exploit the

situation. Though initially opposed to any public association with King, he

soon matched his brother’s impulsiveness by calling Georgia judge Oscar

Mitchell to demand King’s release from prison. Following some additional

prodding from Atlanta’s progressive mayor, William Hartsfield, Mitchell

complied, and after eight harrowing days behind bars King was out on bail.

Following a joyful reunion with his family, King expressed his gratitude to

the Kennedy brothers—and his intention to vote Democratic, something he

had not done in previous presidential elections. Coming during the final week

of the campaign, this delighted Kennedy’s staff. But the best was yet to come.

On the Sunday before the election, more than two million copies of a pro-

Beside the Weary Road 91

Kennedy pamphlet entitled The Case of Martin Luther King: “No Comment”

Nixon Versus a Candidate with a Heart appeared in black churches across the

nation, thanks in part to the efforts of Gardner Taylor, a leading figure in the

National Baptist Convention who also served on the National Council of

CORE. Later known as the “blue bomb,” the brightly colored comic-book-

style pamphlet produced a groundswell of support for Kennedy, who received

approximately 68 percent of the black vote, 8 percent more than Adlai

Stevenson had garnered in 1956. Some observers even went so far as to sug-

gest that Kennedy, who defeated Nixon by a mere 114,673 votes in the clos-

est presidential election to date, owed his victory to a late surge in black

support.

50

Kennedy’s election brought renewed hope of federal civil rights enforce-

ment. Even though he said relatively little about race or civil rights during

the fall campaign, and the calls to Coretta King and Judge Mitchell were not

much to go on, most civil rights advocates reasoned that the young president-

elect could hardly be worse than Dwight Eisenhower. Personally conserva-

tive on matters of race and preoccupied with the Cold War and foreign affairs,

Eisenhower had allowed the executive branch’s commitment to civil rights

to lag far behind that of the federal courts. While Kennedy, too, was an in-

veterate Cold Warrior with a weak civil rights record, the soaring rhetoric of

the New Frontier suggested that the new president planned to pursue an

ambitious agenda of domestic reform that included civil rights advances.

Despite his reluctance to make specific promises, he often talked about the

moral imperatives of a true democracy, and on one occasion he even alluded

to the need for a presidency that would “help bring equal access to public

facilities from churches to lunch counters and . . . support the right of every

American to stand up for his rights, even if on occasion he must sit down for

them.” This implicit endorsement of the sit-ins did not go unnoticed in the

civil rights community, though by inauguration day there were increasing

Presidential candidates

John F. Kennedy and

Richard M. Nixon, with

moderator and CBS

newsman Howard K.

Smith, following a

presidential debate held in

Chicago in September

1960. (Getty Photos)

92 Freedom Riders

suspicions that Kennedy’s commitment to social change was more rhetorical

than real. Civil rights leaders were disappointed when he passed over Wofford

and appointed Burke Marshall, a corporate lawyer with no track record on

civil rights, as the assistant attorney general for civil rights, and they were

stunned when he failed to mention civil rights in his inaugural address—or

to include Martin Luther King in the list of black leaders invited to the inau-

guration. These mixed signals left King and others in a state of confusion,

though most activists remained hopeful that the arc of American politics was

at least tilting toward racial justice.

51

As Washington and the nation weathered the transition to the Kennedy

administration, CORE experienced its own administrative overhaul. A staff

revolt against executive secretary Jimmy Robinson, who left on an extended

European vacation in October, prompted a general bureaucratic reorganiza-

tion and a search for someone to fill the newly created position of national

director. “Jimmy Robinson was skilled at fund raising, a tiger on details, and

as fiercely dedicated as anyone alive,” Jim Farmer recalled many years later.

“But he was unprepossessing and could not lead Gideon’s army, nor sound

the call for battle. Furthermore he was white. If CORE was to be at the

center of the struggle, its leader and spokesperson had to be black.”

The search for a national director quickly focused on King, who briefly

entertained an offer tendered by search committee chair Val Coleman. At

first King agreed to consider the offer if CORE would consent to a formal

merger with SCLC, but the obvious impracticality of combining a secular,

Northern-based organization with a group of devout, Southern black minis-

ters soon convinced him to withdraw his name from consideration. The

committee’s second choice was Farmer, who had been languishing as a mi-

nor official at the national NAACP office since 1959. Frustrated by the cau-

tious policies and bureaucratic inertia of Roy Wilkins and other NAACP

leaders, Farmer leaped at the chance to rejoin and lead the organization that

he had helped to found nineteen years earlier. When Wilkins heard about

the offer, he urged Farmer to take it and even acknowledged a bit of envy.

“You’re going to be riding a mustang pony,” he confessed to his departing

assistant, “while I’m riding a dinosaur.”

52

3

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’

Stand up and rejoice! A great day is here!

We’re fighting Jim Crow and the victory’s near!

Hallelujah! I’m a-travelin’, Hallelujah, ain’t it fine.

Hallelujah! I’m a-travelin’ down freedom’s main line!

—1961 freedom song

1

TRUE TO WILKINS’S PREDICTION, Farmer’s directorship of CORE began with

a gallop. His first day on the job, February 1, 1961, was the first anniversary

of the Greensboro sit-in, and all across the South demonstrators were en-

gaging in commemorative acts of courage. As Farmer sat at his desk that first

morning waiting for reports from the Southern front, he made his way through

a stack of accumulated correspondence. Among the letters that caught his

attention were several inquiries about Boynton v. Virginia, a recent Supreme

Court decision involving Bruce Boynton, a Howard University law student

from Selma, Alabama, arrested in 1958 for attempting to desegregate the

whites-only Trailways terminal restaurant in Richmond. In December 1960

the Court overturned Boynton’s conviction by ruling that state laws mandat-

ing segregated waiting rooms, lunch counters, and restroom facilities for in-

terstate passengers were unconstitutional. With this ruling, the Court

extended the 1946 Morgan decision, which had outlawed legally enforced

segregation on interstate buses and trains. But, according to the letter writ-

ers, neither of these decisions was being enforced. Why, they asked, were

black Americans still being harassed or arrested when they tried to exercise

their constitutional right to sit in the front of the bus or to drink a cup of

coffee at a bus terminal restaurant?

At a late-morning meeting, Farmer relayed this troubling question to

his staff. To his surprise, two staff members had already come up with a

94 Freedom Riders

tentative plan to address the problem of nonenforcement. As Gordon Carey

explained, during an unexpectedly long bus trip from South Carolina to New

York in mid-January he and Tom Gaither had discussed the feasibility of a

second Journey of Reconciliation. Adapting the phrase “Ride for Freedom”

originated by Billie Ames in the mid-1950s, they had come up with a catchy

name for the project: “Freedom Ride.” Thanks to a blizzard that forced them

to spend a night on the floor of a Howard Johnson’s restaurant along the

New Jersey Turnpike, they had even gone so far as to map out a proposed

route from Washington to New Orleans. Patterned after Gandhi’s famous

march to the sea—throughout the bus trip Carey had been reading Louis

Fisher’s biography of Gandhi—the second Journey, like the first, would last

two weeks. But, taking advantage of the Southern movement’s gathering

momentum, it would also extend the effort to test compliance with the Con-

stitution into the heart of the Deep South. Despite the obvious logistical

problems in mounting such an effort, everyone in the room—including

Farmer—immediately sensed that Carey and Gaither were on the right track.

By the end of the meeting there was a consensus that the staff should seek

formal approval of the project at the next meeting of CORE’s National Ac-

tion Committee, scheduled for February 11–12 in Lexington, Kentucky.

There was also general agreement that, unlike the more staid “Journey of

Reconciliation,” the name “Freedom Ride” was in keeping with “the scrappy

nonviolent movement that had emerged” since the Greensboro sit-ins. As a

symbol of the new CORE, the project, in Farmer’s estimation, required a

name that expressed the organization’s determination to put “the movement

on wheels . . . to cut across state lines and establish the position that we were

entitled to act any place in the country, no matter where we hung our hat and

called home, because it was our country.”

2

Later in the day, as the news of sit-ins and mass arrests reached the CORE

office, Farmer became even more convinced that the time was right for a

bold initiative in the Jim Crow South. In Nashville, James Bevel, Diane Nash,

and dozens of other local black activists celebrated the Greensboro anniver-

sary by picketing downtown movie theaters, and in Rock Hill, South Caro-

lina, Gaither and nine others ended up in jail after staging a sit-in at a

segregated McCrory’s lunch counter. When nine of the ten Rock Hill defen-

dants chose thirty days on a road gang rather than a hundred-dollar fine, the

“jail–no bail” policy that CORE had been advocating for nearly a year took

on new life. As Farmer later recalled, he and his staff “felt that one of the

weaknesses of the student sit-in movement of the South had been that as

soon as arrested, the kids bailed out. . . . This was not quite Gandhian and

not the best tactic. A better tactic would be to remain in jail and to make the

maintenance of segregation so expensive for the state and the city that they

would hopefully come to the conclusion that they could no longer afford it.

Fill up the jails, as Gandhi did in India, fill them to bursting if we had to.”

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 95

The courage of the Rock Hill Nine was a major topic of conversation

when SNCC leaders met in Atlanta on February 3. Jim Lawson had always

encouraged his Nashville followers to refuse bail—both as a matter of prin-

ciple and as an effective tactic—but to date no one in SNCC had chosen to

remain behind bars. A heated discussion of the Rock Hill situation and other

topics engaged the SNCC leaders well into the night but seemed to be going

nowhere until a phone call from Gaither focused their attention. Speaking

from a York County Jail phone, Gaither promised them that the Rock Hill

Nine were committed to serving out their thirty days of hard labor, but he

pleaded for reinforcements that would magnify the impact of the Rock Hill

jail-in. He wanted SNCC’s student activists to put their own bodies on the

line. They could stage jail-ins in other cities, or they could come to Rock

Hill to share the pleasures of the York County road gang, but they had to do

something dramatic to sustain the momentum of the movement.

Following the call, four students—Diane Nash of Fisk, Charles Jones of

Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, Ruby Doris Smith of Atlanta’s

Spelman College, and Charles Sherrod of Virginia Union Seminary—vowed

to join the Rock Hill Nine. The next day the four volunteers were on their

way to South Carolina and jail. A SNCC press release urging other nonvio-

lent activists to join the second wave of Rock Hill inmates found no takers,

but the jail-in movement soon spread to Atlanta and Lynchburg, Virginia,

raising the total number of students choosing jail over bail to nearly one

hundred. As the Rock Hill Thirteen served out their month in jail, the bond

between SNCC and CORE tightened, creating a legend of solidarity and

sacrifice that would inspire later activists. On February 12, Abraham Lincoln’s

Birthday, more than a thousand marchers, some local and some from as far

away as Florida, demonstrated their support with a “pilgrimage to Rock Hill,”

suggesting that Gaither and CORE had started something big.

3

After his release on March 2, Gaither traveled to New York, where he

was greeted as a hero by his CORE colleagues. By this time the office was

abuzz with tentative plans for a Freedom Ride scheduled for early May. Three

weeks earlier, on the same day as the Rock Hill pilgrimage, the Ride had

received the official endorsement of CORE’s National Action Committee.

Several members of the committee were old enough to remember the excite-

ment surrounding the Journey of Reconciliation, and the gathering in Lex-

ington embraced the staff’s proposal as a welcome reprise of CORE’s most

celebrated project. Prior to the meeting, Farmer had been unsure about the

committee’s receptivity to such a daring and costly project, so he and his staff

came away from the Lexington meeting with a mixture of relief and elation.

The committee’s decision was especially gratifying to CORE-lator editor Jim

Peck, the only veteran of the Journey still active as a CORE leader. Having

waited fourteen years for a second freedom ride, he felt a sense of vindica-

tion, and his only regret was that neither George Houser nor Bayard Rustin

was close at hand to witness the rebirth of their dream. Both men, of course,