Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

56 Freedom Riders

2

Beside the Weary Road

And ye, beneath life’s crushing load, Whose forms are bending low,

Who toil along the climbing way With painful steps and slow,

Look now! For glad and golden hours Come swiftly on the wing:

O rest beside the weary road, And hear the angels sing.

—from the hymn “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear”

1

DESPITE THE STUBBORN PERSISTENCE of segregated travel in the late 1940s,

most CORE activists regarded the Journey of Reconciliation as a qualified

success. Some even talked of organizing a series of interracial rides and other

direct action challenges to Jim Crow in the Deep South. Speaking at an April

1948 Council Against Intolerance in America dinner in New York, Bayard

Rustin hailed the Journey as the first of many interracial bus rides and “a

training ground for similar peaceful projects against discrimination in em-

ployment and the armed services.” At the time, neither he nor anyone else in

CORE suspected that more than a decade would pass before even one more

“freedom ride” materialized.

During the early 1950s CORE and the broader nonviolent movement

entered a period of steady decline. As Jim Peck later recalled, “These were

CORE’s lean years—the years when social consciences throughout the United

States were numbed by the infection of McCarthyism.” In the 1960s civil rights

advocates of all persuasions would become adept at turning the Cold War to

their advantage by pointing out the international vulnerability of a nation that

failed to practice what it preached on matters of race and democracy. But this

was not the case in the 1950s, before the decolonization of Africa and Asia

heightened State Department sensitivity to public opinion in the “colored”

nations of the Third World. Plagued by anti-radical repression, an uncertain

relationship with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and nagging factionalism,

Beside the Weary Road 57

CORE lost its momentum and most of its active membership by mid-decade.

As the cautious optimism of the immediate postwar era dissolved into a struggle

for organizational and ideological survival, several of CORE’s early stalwarts,

including Rustin and Farmer, redirected their energies elsewhere. Outside of

the Baltimore and St. Louis chapters there was little activity or enthusiasm,

and to make matters worse, the beleaguered FOR withdrew most of its finan-

cial support in 1953, forcing the resignation of executive director George

Houser, technically an FOR staff member on loan to CORE.

2

Following Houser’s departure in early 1954, the burden of leadership

fell upon the shoulders of Peck, the editor of the organization’s newsletter

CORE-lator, and Billie Ames, a talented and energetic St. Louis woman who

served as CORE’s national group coordinator. In the summer of 1954, Ames

tried to revive CORE’s flagging spirit by proposing a “Ride for Freedom,” a

second Journey of Reconciliation that would recapture the momentum of

the organization’s glory days. Ames planned to challenge segregated railway

coaches and terminals as far south as Birmingham, but the project collapsed

when the NAACP, which had provided legal support for the original 1947

freedom ride, refused to cooperate. Arguing that an impending Interstate

Commerce Commission ruling made the “Ride for Freedom” unnecessary,

NAACP leaders advised CORE to devote its attention “to some other pur-

pose.” This disappointment, combined with continuing factionalism and dis-

sension, brought CORE to the verge of dissolution. After personal problems

forced Billie Ames to leave in March 1955, some wondered if the organiza-

tion would last the year. In desperation, the delegates to the 1955 national

convention voted to hire a national field organizer with experience in the

South. Encouraged by the formation of a small student chapter in Nashville

earlier in the year, many regarded the South as CORE’s last best hope. Even

though the potential for successful nonviolent direct action in the region was

unproven, the organization had few options at this point.

3

In early December 1955, during the same fateful week that witnessed

the arrest of Rosa Parks—a forty-three-year-old black seamstress and NAACP

leader who refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus—

LeRoy Carter became CORE’s first national field organizer. A former

NAACP field secretary with twenty years of experience in the civil rights

struggle, Carter seemed well suited to the task of spreading the CORE phi-

losophy to the South. Soft-spoken and deliberate, yet full of determination,

he could have been an important asset to the cause of nonviolent resistance

in the Deep South, especially during the early weeks of the bus boycott trig-

gered by Parks’s arrest. Led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—the charismatic

twenty-six-year-old minister of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

and newly elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association

(MIA)—the boycotters faced an uphill struggle against local white suprema-

cists and were in desperate need of help. Unfortunately for King and the

MIA, the national leadership of CORE was slow to react to the unexpected

58 Freedom Riders

events in Alabama and did not dispatch Carter to Montgomery until late

March 1956. Despite its obvious affinity for what was happening in Alabama,

CORE did not rush to embrace the Montgomery movement and made no

attempt to associate itself with the MIA during the first three months of the

boycott. Convinced that the Montgomery protest would soon collapse, CORE

activists worried that the boycotters’ untutored efforts would do more harm

than good by seemingly demonstrating the futility of direct action in the

Deep South. When James Robinson, CORE’s finance secretary, composed a

fund-raising letter in early February highlighting the potential for direct ac-

tion in the South, he avoided any mention of the controversial bus boycott in

Montgomery.

4

Such disdain all but disappeared in late February, of course, when the

mass arrest of boycott leaders, including King and several dozen other black

ministers, turned the Montgomery protest into front-page news and a na-

tional cause célèbre. Realizing that they had misjudged the situation, embar-

rassed CORE leaders scurried to make up for lost time. On February 22 a

group of local CORE enthusiasts organized a Montgomery chapter, and a

month later the national council of CORE adopted a resolution commend-

ing the boycotters “for their vision, courage, and steadfastness of purpose in

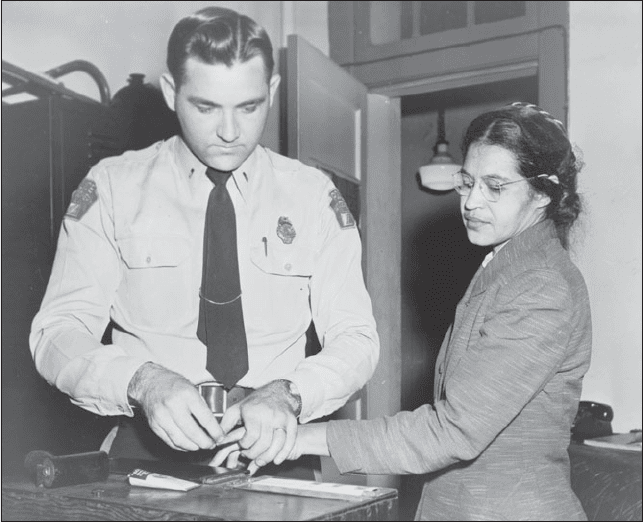

Rosa Parks is fingerprinted by a Montgomery, Alabama, policeman in February

1956, following the mass indictment of MIA leaders. (Library of Congress)

Beside the Weary Road 59

sustaining a significant struggle against a great evil, and at the same time

pioneering in the mass use in this country of a technique and spirit which

holds unlimited promise for use elsewhere against oppression.” The council

also voted to send Carter to Montgomery.

In early April, Carter spent several days conferring with King and other

MIA leaders, but it soon became evident that he had arrived too late to exert

any measurable influence on the Montgomery movement. While the boycott-

ers welcomed CORE’s support, they were understandably wary of an organi-

zation that presumed to teach them the “rules” of nonviolent protest. Even

King, who knew something about CORE’s long-standing commitment to di-

rect action, had mixed feelings about what appeared to be a belated and op-

portunistic attempt to capitalize on the boycotters’ struggle. To his surprise,

when the spring 1956 issue of CORE-lator ran a picture of MIA officials stand-

ing on the steps of the Holt Street Baptist Church, it identified them as the

“leaders of the CORE-type protest in Montgomery.” In the accompanying

story, editor Jim Peck proclaimed that “the CORE technique of non-violence

has been spotlighted to the entire world through the effective protest action

which the Montgomery Improvement Association has been conducting since

December 5.” And in an adjoining column, Peck proudly quoted a New York

Post article that reminded the world that CORE had employed Gandhian tech-

niques “long before Montgomery joined the passive resistance movement.”

5

For Peck, as for most CORE veterans, the “miracle of Montgomery” was

a bittersweet development. Having suffered through the lean years of the early

1950s, when nonviolent resistance was routinely dismissed as an irrelevant pipe

dream, they could not help viewing the boycott with a mixture of pride and

jealousy. “I had labored a decade and a half in the vineyards of nonviolence,”

Jim Farmer explained in his 1985 memoir. “Now, out of nowhere, someone

comes and harvests the grapes and drinks the wine.” He, along with most of his

colleagues, eventually overcame such feelings, acknowledging that Montgom-

ery gave nonviolence a new legitimacy and probably saved CORE from extinc-

tion. As he put it: “No longer did we have to explain nonviolence to people.

Thanks to Martin Luther King, it was a household word.” But such gracious-

ness was the product of years of reflection and common struggle. In the uncer-

tain atmosphere of the mid-1950s, charity did not come so easily, even among

men and women who had dedicated their lives to social justice.

6

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was an important connecting link be-

tween the nonviolent movement of the 1940s and the freedom struggle of

the 1960s. And it was also part of a great historical divide. Along with the

Brown decision, the rise of massive resistance in the white South, and other

related developments of the 1950s, the boycott and the subsequent emer-

gence of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) radically

altered the context of racial and regional conflict. Even more important, the

1950s was an era of broad and deep social change. In the international arena,

the passing of the Stalinist regime, the escalating tensions of the Cold War,

60 Freedom Riders

the nuclear arms race, the economic recovery of Europe, and the decoloniza-

tion of the Third World brought a new tone to world affairs. The pace of

change was equally dramatic on the domestic front, as significant shifts in

political, legal, and popular culture transformed the nature of American life.

The anti-Communist excesses of McCarthyism, the “rights revolution” ini-

tiated by the Warren Court, the proliferation of television, the growing in-

fluence of consumerism and corporate power, the emergence of a distinct

youth culture that found expression in the racially subversive medium of

rock ’n’ roll, the desegregation of professional sports and the entertainment

industry, and the massive postwar migration of blacks to the North and whites

to the suburbs all contributed to this transformation. In many cases, the full

impact of these changes did not become manifest until the mid-1960s, but

the relative calm of the Eisenhower years should not obscure the shifting

realities that the fifties represented—realities that helped to lay the ground-

work for the social upheavals of the following decade.

As difficult as they are to unravel, the themes of continuity and disconti-

nuity are an important part of the Freedom Rider story. The celebrated Free-

dom Rides of 1961 represented a reprise of the lesser-known Journey of

Reconciliation of 1947, and the tactics, guiding philosophy, organizational

roots, and goals of these two experiments in nonviolent resistance were strik-

ingly similar. Yet the impact—and the ultimate meaning—of the two histori-

cal episodes could hardly have been more different. While the Journey brought

about little change and was soon forgotten by all but a handful of nonviolent

activists, the Freedom Rides triggered a major political crisis that forced the

federal government to fulfill an unkept promise to desegregate public tran-

sit, revitalizing the nonviolent movement and bringing direct action to the

forefront of a widening struggle. This contrast in consequences can be traced

to a number of factors, including chance and a web of contingency, but the

relative success of the Freedom Rides was largely a function of historical

context. America—and the world—was a different place in 1961, especially

with respect to expectations of racial and social change. For those who dreamed

of a nonviolent transformation of American race relations, there were new

strands of experience and hope that subverted the moral authority of white

culture—strands from which the fabric of the modern civil rights movement

was woven. To understand how the seemingly overmatched activists of CORE

marshaled enough courage and conviction to launch the Freedom Rides, we

need to take a close look at what happened to the civil rights struggle be-

tween 1955 and 1961—first in Montgomery, and later in other centers of

racial insurgency.

7

CORE’S FORMAL INVOLVEMENT in the Montgomery Bus Boycott never

amounted to much, but this was not the case with CORE’s parent organiza-

tion. Largely through the efforts of Bayard Rustin, FOR exerted a powerful

influence on the emerging historical, political, and ideological consciousness

Beside the Weary Road 61

of King and other MIA leaders. The first national civil rights leader to grasp

the full significance of what was happening in Montgomery, Rustin thrust

himself into the center of the struggle. He wanted the boycotters to broaden

their philosophical horizons and to feel the pride and responsibility of being

part of a worldwide movement for human rights. Styling himself a Gandhian

sage, he became convinced that he was the one person who could show them

how to make the most of an extraordinary opportunity. Though virtually

unknown to the general public, he was a revered figure in the international

subculture of Gandhian intellectuals. No one who met him could fail to be

impressed by the quality of his mind and his deep commitment to nonvio-

lence, not to mention his boundless energy. Those who knew him well, how-

ever, were painfully aware of another side of his life. In an age when

homosexuality was associated with social and political subversion, his per-

sonal life was a source of concern and embarrassment for FOR, a fragile

organization that could ill afford a major scandal. After several encounters

with the vice squad and a stern reprimand from the normally placid A. J.

Muste, Rustin promised to behave, but in June 1953 an arrest for lewd and

lascivious behavior in Pasadena, California, led to a thirty-day jail term and

his resignation from the FOR staff. By the time he returned to New York to

pick up the pieces of his life, even some of his closest friends had concluded

that the nonviolent movement might be better off without him. Although he

soon found a haven at the War Resisters League, which offered him a posi-

tion as executive secretary, Rustin’s career as an influential activist appeared

to be over. He, of course, felt otherwise. All he needed was a chance to re-

deem himself, an opportunity to use his hard-earned wisdom to demonstrate

the liberating power of nonviolence. Amazingly, he would soon find what he

was looking for—not in New York or Chicago or any of the other cities that

had witnessed the courage of FOR and CORE activists, but rather in the

faraway streets of Montgomery.

8

Soon after the boycott began, the radical white Southern novelist Lillian

Smith, who had once served on the national board of FOR, wired Rustin and

urged him to offer his assistance to King and the MIA. If someone with expe-

rience in Gandhian tactics could bring his knowledge to bear on the situa-

tion, she suggested, the boycotters might have a real chance to sustain their

movement. Rustin had never been to Alabama, but as he pondered Smith’s

suggestion and mulled over the early news reports on the boycott, a bold

plan began to take shape. If he could find a sponsor, he would “fly to Mont-

gomery with the idea of getting the bus boycott temporarily called off ”; then,

with the help of FOR, he would organize “a workshop or school for non-

violence with a goal of 100 young Negro men who will then promote it not

only in Montgomery but elsewhere in the South.” In early January he shared

his thoughts with several friends at FOR but found little enthusiasm for his

plan. Charles Lawrence, FOR’s national chairman, not only questioned the

wisdom of suspending an ongoing protest but also worried “that it would be

62 Freedom Riders

easy for the police to frame him [Rustin] with his record in L.A. and New York,

and set back the whole cause there.” FOR executive director John Swomley

shared Lawrence’s concern, as did the socialist leader Norman Thomas, who

thought Rustin was “entirely too vulnerable on his record.” “This young King

is doing well. Bayard is considered a homosexual, a Communist and a draft

dodger. Why do you put such a burden on King?” Thomas asked.

9

Eventually Rustin found a more sympathetic audience in Phil Randolph

and Jim Farmer, but even they had strong misgivings about dispatching a

homosexual ex-Communist to a conservative Deep South city. Though he

admired Rustin’s bravado, Randolph agreed to fund the trip only after it

became clear that his old friend was prepared to hitchhike to Montgomery if

necessary. After a telephone call to King confirmed that the MIA would wel-

come Rustin’s visit, only the details needed to be worked out. Rustin wanted

Bob Gilmore of the American Friends Service Committee to accompany him

and to act as a liaison with the white community in Montgomery. Randolph

and Farmer, fearing that an interracial team would be too conspicuous, turned

instead to Bill Worthy, a thirty-four-year old black reporter for the Baltimore

Afro-American. A seasoned activist, Worthy had participated in a number of

FOR and CORE campaigns, including the Journey of Reconciliation. Nev-

ertheless, the decision to send him to Montgomery as Rustin’s unofficial chap-

erone was one that Randolph and Farmer would later regret. In 1954 Worthy

had raised the hackles of the State Department with a series of sympathetic

stories on the Soviet Union, and his presence in Montgomery only served to

exacerbate the fear that Communists had infiltrated the MIA.

10

As fate would have it, Rustin and Worthy arrived in Montgomery on

Tuesday, February 21, the day of the mass indictments. The MIA office was

in chaos. Rustin asked to speak to King but was told that the MIA president

was in Nashville, preaching at Fisk University. At this point no one in the

MIA, other than King, had the faintest idea who Rustin was. Nevertheless,

he soon talked his way into the office of King’s close friend, the Reverend

Ralph Abernathy, who after a brief conversation warned his visitor that Mont-

gomery was a dangerous place for an unarmed black activist. Undaunted,

Rustin found his way to E. D. Nixon, a longtime and seemingly fearless

NAACP and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters activist, who became an

instant ally after Rustin produced a letter of introduction from Randolph.

For more than an hour, Nixon briefed Rustin on the boycotters’ situation,

which was obviously growing more perilous by the day. “They can bomb us

out and they can kill us,” he vowed, “but we are not going to give in.” For a

time Rustin simply listened, but when Nixon confessed that he was not sure

how the boycotters should respond to the mass indictments, the veteran ac-

tivist promptly suggested the Gandhian option of voluntarily filling the jails.

As Rustin laid out the rationale for nonviolent martyrdom, Nixon became

intrigued, and the next morning he became the first boycott leader to turn

himself in. “Are you looking for me?” he asked a stunned sheriff’s deputy.

Beside the Weary Road 63

“Well, here I am.” Once the news of Nixon’s arrest got out, there was a

virtual stampede at the county courthouse, as scores of black leaders joined

in the ritual of self-sacrifice. Through it all Rustin was on the scene, dispens-

ing advice and encouragement and basking in the knowledge that, although

he had been in Montgomery for less than a day, he had already made a differ-

ence. Even Worthy, who had seen his friend in action many times before,

was impressed, though he worried that this early triumph would feed Rustin’s

reckless spirit and ultimately lead to trouble.

11

Trouble was not long in coming. On Wednesday evening, after attend-

ing a rousing prayer meeting at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Rustin de-

cided to pay a visit to Jeanette Reece, who a week earlier had been frightened

into dropping her legal challenge to segregated buses. To Rustin’s surprise,

Reece’s home was under police surveillance. As he approached the front door,

he was immediately accosted by gun-waving white policemen who demanded

to know who he was. Rustin assured them that he just wanted to talk to Reece

and that he meant her no harm. The officers continued to press him for

some identification. On the verge of being arrested, he blurted out: “I am

Bayard Rustin; I am here as a journalist working for Le Figaro and the Manches-

ter Guardian.” This seemed to satisfy the policemen, who granted him a brief

interview with Reece, but the impromptu cover story would later come to

haunt him.

Having narrowly escaped arrest, a somewhat chastened Rustin finally

met Dr. King on Thursday morning, following the boycott leader’s booking

at the county courthouse. Surrounded by dozens of reporters and a throng of

cheering supporters, King had little time to greet visitors, but at Nixon’s

urging he invited Rustin to a late-morning strategy session of the MIA ex-

ecutive committee. At the session, Rustin was impressed by King’s intelli-

gent, forthright leadership, and he

was thrilled when the committee

voted to turn the MIA’s traditional

mass meetings into prayer meet-

ings. After King and his colleagues

agreed that all future meetings

would center around five prayers,

including “a prayer for those who

oppose us,” he knew that he had

underestimated his Southern hosts.

The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, the

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.,

and Bayard Rustin leave the

Montgomery County Courthouse,

February 23, 1956. (AP Wide

World)

64 Freedom Riders

In their own untutored way, he now realized, the boycotters had already

begun to master the art of moral warfare. Although he still had doubts about

the depth of the MIA’s commitment to nonviolence, his original plan for a

temporary suspension of the boycott no longer seemed realistic or necessary.

As he told King later that afternoon, in all his travels, even in India and Af-

rica, he had never witnessed anything comparable to the Montgomery move-

ment. The boycotters’ accomplishments were already remarkable. With a

little help from the outside—with the proper publicity, with a disciplined

and carefully constructed long-range strategy, and with enough funds to hold

out against the die-hard segregationists—the Montgomery story could be-

come a beacon for nonviolent activists everywhere. To this end, he and his

friends at FOR were ready to help in any way they could. Though still a bit

puzzled by this strange visitor from New York, King thanked Rustin for his

gracious offer and invited him to the MIA’s Thursday evening prayer meet-

ing at the First Baptist Church.

What Rustin witnessed that evening confirmed his growing optimism.

The meeting at First Baptist was the first mass gathering since the arrests,

and the spirit that poured out of the overflow crowd was like nothing Rustin

had ever seen. When the ninety indicted leaders gathered around the pulpit

to open the meeting, the sanctuary exploded with emotion. As Rustin later

described the scene:

Overnight these leaders had become symbols of courage. Women held their

babies to touch them. The people stood in ovation. Television cameras

ground away, as King was finally able to open the meeting. He began: “We

are not struggling merely for the right of Negroes but for all the people of

Montgomery, black and white. We are determined to make America a bet-

ter place for all people. Ours is a non-violent protest. We pray God that no

man shall use arms.”

Near the close of the meeting, one of the speakers seized the moment to

declare that Friday would be a “Double-P Day,” a time for prayer and pil-

grimage; the car pools would be suspended, private cars would be left at home,

and everyone would walk. This gesture was almost too much for Rustin, who

after years of lonely struggle could hardly believe what he was witnessing.

Later that evening he called John Swomley in New York and breathlessly

related what he had seen. The Montgomery movement had unlimited po-

tential, he reported, but the boycotters were in desperate need of assistance—

not only money for legal fees but also veteran activists who could teach them

the finer points of nonviolence. In the short run, he would do what he could,

but he urged Swomley to alert Muste and Randolph that a full mobilization

of resources was in order.

True to his word, Rustin maintained a hectic schedule in the days that

followed. On Friday and Saturday, he discussed strategy with the executive

committee, sat in on a meeting of the car pool committee, survived an awk-

ward interview with Robert Hughes, the executive director of the Alabama

Beside the Weary Road 65

Council on Human Relations, and even helped a group of volunteers de-

sign a new logo for the MIA. The climax of his whirlwind tour came on

Sunday, when he spent most of the day with King. The day began with

morning services at Dexter, where the young minister preached a moving

sermon on the philosophy of nonviolence. “We are concerned not merely

to win justice in the buses,” King explained, “but rather to behave in a new

and different way—to be non-violent so that we may remove injustice it-

self, both from society and from ourselves.” Later, during a private dinner

at the parsonage, King briefed Rustin on the boycott. Rustin listened at-

tentively, but as the evening progressed he began to regale his hosts with

tales of Harlem and the Northern underground. Coretta Scott King, who

suddenly recalled that she had heard Rustin speak at Antioch College in

the early 1950s, was utterly charmed, and her husband was captivated by

his guest’s sweeping vision of social justice. For several hours Rustin and

the Kings discussed religion, pacifism, nonviolent resistance, and other moral

imperatives, and by the end of the evening a deep philosophical and per-

sonal bond had been sealed. Despite periodic disagreements over strategy

and a serious falling-out in the early 1960s, they would remain close friends

until King’s assassination in 1968.

12

Not everyone in the MIA was so enamored with the strange visitor from

New York. Within hours of Rustin’s arrival, there were complaints about

“outside agitators” and rumors that subversives were trying to take over the

Montgomery movement. Even those who dismissed these fears as ground-

less worried about the MIA’s credibility and public image. Despite the recent

eclipse of Senator Joseph McCarthy, fear of Communist infiltration was still

rife in the United States, even among black Americans. No popular move-

ment could afford the taint of Communism, especially in a state where the

Scottsboro case was a relatively recent memory. In Deep South communities

like Montgomery, smooth-talking outsiders like Rustin were always a little

suspect, but any chance he had of gaining broad acceptance ended when he

posed as a European correspondent. When word got around that the editors

of Le Figaro and the Manchester Guardian had never heard of him, Rustin’s

situation in Montgomery became precarious. Several of the national report-

ers covering the mass indictment story knew the true identity and background

of both Rustin and Worthy, and the inevitable murmurings soon alerted the

local press and police. Rustin was having the time of his life and was deter-

mined to hang on as long as he could, but by the end of his first week in town,

there were enough cold stares and wary handshakes to convince him that his

days in Montgomery were numbered. Reluctantly he informed Swomley and

the FOR staff that sooner or later he would need a replacement. Swomley,

who had opposed Rustin’s venture from the outset, needed no prodding to

send one. Indeed, Glenn Smiley, FOR’s national field secretary, was already

on his way to Montgomery.

13

Smiley and Rustin were old friends and compatriots, but they were strik-

ingly different in style and temperament. Though he was roughly the same