Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

126 Freedom Riders

other Riders. With some justification, Farmer worried that the untried re-

cruit might not be able to hold his tongue or his fists if provoked. Fortu-

nately, while Farmer was still mulling over his options, the Winnsboro police

dropped all charges against Thomas, releasing him around midnight.

While Peck was still languishing in his cell, two policemen drove Thomas

to Winnsboro’s partially closed and virtually empty bus station. As the police

sped off, Thomas noticed several white men standing in the parking lot, look-

ing to his eyes very much like a potential lynch mob. One of the men, upon

seeing him, ordered him to “go in the nigger waiting room.” Somehow the

young Freedom Rider summoned up enough courage to enter the white wait-

ing room, purchase a candy bar, and stroll past “gaping segregationists” who

seemed stunned by his defiance. Before the whites could react, a local black

minister whom Frances Bergman had called earlier in the day drove up to the

waiting room entrance and literally screamed at Thomas to “get in the car and

stay down.” As Thomas recalled years later: “We expected gunshots, but they

didn’t come. He saved my life that night, because they were going to kill me.”

After the rescue, the minister drove Thomas twenty-five miles south to Co-

lumbia, where the Freedom Rider found refuge in the home of a local NAACP

leader. The next day Thomas took a bus to Sumter to rejoin the other Riders—

including Peck, who had his own tale to tell.

The Winnsboro police had planned to release Peck and Thomas at

roughly the same time, but after dropping the original arrest-interference

charge against Peck, local officials immediately rearrested him for violating a

state liquor law. Though unsure of their legal standing on the matter of seg-

regation, they found a way to extend Peck’s ordeal by turning to an obscure

South Carolina statute that prohibited the importation of untaxed liquor into

the state. Two days earlier, just prior to crossing the South Carolina line,

Peck and the Trailways group had stopped for a few minutes at a small ter-

minal attached to a liquor store. Thinking that some alcoholic sustenance

might come in handy during the difficult days ahead, Peck purchased a bottle

of imported brandy, which he promised to share with his fellow Riders. This

produced a few wry comments from Farmer and others familiar with Peck’s

fondness for hard liquor, but no one realized that he was about to violate

South Carolina law.

Two days later, as Peck was about to be released from the Winnsboro

jail, a police officer spied the bottle of whiskey and proudly informed his

superiors that the bottle lacked the required South Carolina state liquor stamp.

Within minutes Peck was back in jail, charged with illegal possession of un-

taxed alcohol. Upon learning of Peck’s second arrest, Farmer and a carload

of CORE supporters—including Jim McCain and a local black attorney,

Ernest Finney Jr.—drove from Sumter to Winnsboro, arriving just before

dawn. Securing Peck’s release with a fifty-dollar bail bond, Farmer and

McCain whisked their old friend back to Sumter, knowing full well that they

could not afford to wait for his day in court. Although jumping bail violated

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 127

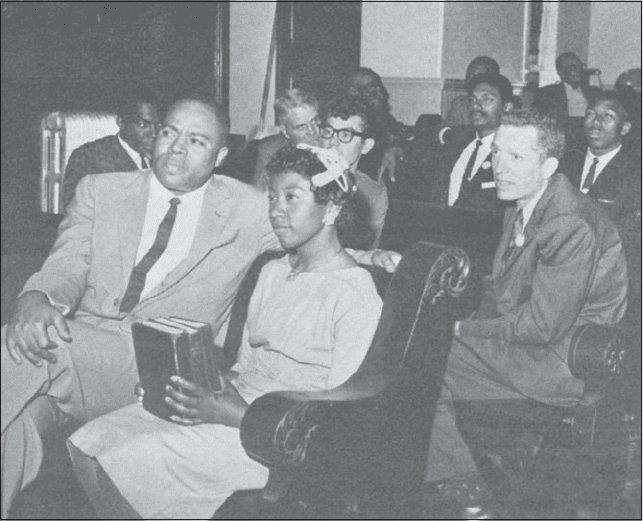

CORE Freedom Riders (left to right) Hank Thomas, Jim Farmer, Mae Frances

Moultrie, Albert Bigelow, Ed Blankenheim, Joe Perkins, Jim Peck, and Charles

Person attend a mass meeting at the Emmanuel AME Church in Sumter, South

Carolina, May 11, 1961. (Photograph by Theodore Gaffney)

CORE policy, Peck, for once, was in no mood to argue the finer points of

legal and organizational responsibility. When Peck and the rescue party

arrived safely at McCain’s house—CORE’s unofficial headquarters in Sumter—

everyone was relieved to be back in the fold. Thomas and Bergman’s re-

appearance later in the day completed the reunion, as the returnees swapped

jail stories and regaled the other Riders with tales of “friendly” Winnsboro.

34

The safe return of Thomas, Peck, and Bergman buoyed the spirits of the

Riders, all of whom were thankful that the schedule called for two days of

rest in Sumter. Aside from a brief test of a bus terminal waiting room—the

small Sumter terminal had no restaurant—the stay in Sumter afforded them

a chance to relax, reflect upon the experiences of the first week on the road,

and gather their strength for the expected challenges to come. At a mass

meeting on Thursday evening at the Emmanuel AME Church, Farmer talked

about the significance of the Freedom Ride, and Peck and Thomas recounted

their harrowing experiences in Winnsboro. But the highlight of the meeting,

according to Moses Newson of the Baltimore Afro-American, was a testimo-

nial by Frances Bergman, who “hushed” the audience with a moving account

128 Freedom Riders

of her rude introduction to the Deep South. “For the first time I felt that I

had a glimpse of what it would be like to be colored,” she confessed. “This

thing made me realize what it is to be scorned, humiliated and made to feel

like dirt. . . . The whole thing was such an eye-opener for me. . . . It left me so

filled with admiration for the colored people who have to live with this all

their lives. It seems to me that anything I can do now, day or night, would

not be enough. . . . Somehow you feel there is a new urgency at this time.

You see the courage all about you.” Rededicating herself to the cause of ra-

cial justice, she praised the activism of young black students but warned that

“older persons” should not “sit back and wait for them to do it.” Despite its

hint of presumption, this admonition struck a responsive chord in the crowd,

which included a number of students from nearby Morris College, a black

Baptist institution that had been a hotbed of sit-in and boycott activity since

the establishment of a campus CORE chapter in March 1960. Here, as in

many other Southern communities, student activists had fashioned a militant

local movement that went far beyond anything that their parents or most

other black community leaders were willing to endorse.

Jim McCain was justifiably proud of the Morris College CORE chapter,

especially after several of the chapter’s stalwarts volunteered to join the Free-

dom Ride. Earlier in the week Farmer had politely brushed off such offers,

but that was before the Ride faced a temporary personnel crisis. Soon after

the Riders’ arrival in Sumter, Cox took a leave of absence to return to High

Point, where he was obliged to deliver a Mother’s Day sermon on Sunday

morning. Thus, with Lewis already gone, the number of Riders was sud-

denly down to eleven, only five of whom were black. Both Lewis and Cox

planned to rejoin the Ride in Birmingham on Monday morning, but CORE

needed at least two substitute Riders for the pivotal three-day journey from

Sumter to Birmingham. Fortunately, with McCain’s help, Farmer not only

found replacements for Lewis and Cox but also added two extra recruits for

good measure. One of the four new Freedom Riders was Ike Reynolds, a

twenty-seven-year-old black CORE activist and Wayne State University

sophomore who had been awakened on Wednesday morning by a 7:00

A.M.

phone call from Gordon Carey. The next thing Reynolds knew, he was on a

midmorning plane from Detroit to Atlanta, where he was picked up and driven

to Sumter. The other recruits—Jerry Moore, Herman Harris, and Mae

Frances Moultrie—were students at Morris College. Moultrie was a twenty-

four-year-old senior from Dillon, South Carolina, and Harris, twenty-one,

and Moore, nineteen, were Northern transplants—Harris from Englewood,

New Jersey, and Moore from the Bronx. Harris was president of the local

CORE chapter and a campus football star, and Moultrie and Moore had

been actively involved in several sit-ins and marches. Trained by McCain, all

three were seasoned veterans of the Southern freedom struggle.

With the new recruits in hand, Farmer, McCain, and the other CORE

staff members spent most of the second day in Sumter assessing the experi-

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 129

ences of the previous week and refining the plan for the remainder of the

Ride. In gauging the future, they had to deal with a number of unknowns,

including the attitudes of black leaders and citizens in Deep South commu-

nities that would inevitably be affected by the Ride. Would the Freedom

Riders be welcomed as liberators? Or would they just as likely be shunned as

foolhardy provocateurs by black Southerners who knew how dangerous it

was to provoke the forces of white supremacy? How many black adults were

ready to embrace the direct action movement that their children had initi-

ated? And how would the student activists themselves respond to an initia-

tive directed by an organization associated with white Northern intellectuals

and an exotic and secular nonviolent philosophy? CORE leaders were hope-

ful, but after a week on the road they still regarded the black South as some-

thing of a puzzle.

Equally perplexing, and far more threatening, was the unpredictability

of white officials in the Deep South—and in Washington. What would the

police do if the Freedom Riders were physically attacked by segregationist

thugs? Would the mayors of cities like Augusta, Birmingham, and Mont-

gomery set aside their avowed segregationist beliefs and instruct their police

chiefs to uphold the law? Would Southern officials enforce the Morgan and

Boynton decisions, now that they knew that at least some members of the

public were aware of the Freedom Ride? Perhaps most important, what would

the Kennedy administration do if white Southerners brazenly violated the

law as interpreted by the Supreme Court? How far would the Justice Depart-

ment go to protect the Freedom Riders’ constitutional rights, knowing that

direct intervention would be politically costly for the administration? The

probable answers to all of these questions remained murky as the Riders set

out on the second week of their southward journey, but with each passing

day CORE leaders felt they were getting a better grasp of what they were up

against, and of what they could expect from friends and foes alike. In particu-

lar, they were fortunate to have the benefit of a remarkable and illuminating

civil rights address delivered earlier in the week by Attorney General Robert

Kennedy.

35

ON SATURDAY, MAY 6, in a Law Day speech at the University of Georgia,

Robert Kennedy issued the first major policy statement of his attorney

generalship. Since no prior attorney general in the post-Brown era had dared

to speak about civil rights in the Deep South, Kennedy’s appearance attracted

considerable press attention, as well as an overflow crowd of students, fac-

ulty, and invited guests. Noticeably absent from the gathering in Athens were

the state’s leading politicians, including Georgia’s governor, Ernest Vandiver.

Kennedy knew, as he reminded the audience, that Georgia had given his

brother the second largest electoral majority in the nation during the recent

election. But he also knew that most of his listeners were segregationists who

would bristle at even the slightest suggestion that the Justice Department

130 Freedom Riders

planned to force the white South to desegregate any time soon. Of the six-

teen hundred persons present, only one—Charlayne Hunter, one of two stu-

dents who had desegregated the university the previous January—was black. It

was in this context that Kennedy faced the ominous task of convincing white

Southerners that he intended to enforce the law in a firm but conciliatory

manner. Knowing that he had to choose his words carefully, he and his staff

had been working on the speech for more than a month.

The result was a clever blend of disarming humor, patriotic rhetoric,

and well-placed candor. After reminding the audience that “Southerners have

a special respect for candor and plain talk,” he got right to the point. “Will

we enforce the civil rights statutes?” he asked rhetorically. “The answer is

yes, yes we will.” His motivation for upholding the civil rights of all Ameri-

cans was rooted in his commitment to equal justice, he told the crowd, but he

was also concerned about the realities of the Cold War: “We, the American

people, must avoid another Little Rock or another New Orleans. We cannot

afford them. . . . Such incidents hurt our country in the eyes of the world.”

Later in the speech he endorsed the Brown decision, condemned the closing

of Prince Edward County’s schools, hailed the first two black students at the

University of Georgia as courageous freedom fighters, and, with an eye to

Southern sensitivity to Northern hypocrisy, promised to put his own house

in order by hiring black staff members at the Justice Department. He also

made it clear that he had no intention of following the lead of the Eisenhower

administration’s passive approach to civil rights. “We will not stand by and

be aloof,” he assured the crowd. “We will move.”

After a few closing remarks, he sat down, hoping that the crowd would

accord him at least a smattering of polite applause. To his surprise, a moment

of awkward silence soon gave way to a long and loud ovation. Whether the

audience was applauding the substance of his remarks or just his courage was

unclear, but most observers judged the speech to be a diplomatic triumph.

According to Ralph McGill, the liberal editor of the Atlanta Constitution, “Never

before, in all its travail of by-gone years, has the South heard so honest and

understandable a speech from any Cabinet member.” While other Southern

editors were somewhat more restrained in their enthusiasm, there was little

negative reaction, even among hidebound conservatives. In the civil rights com-

munity, the speech drew rave reviews; congratulations poured in from every

major civil rights leader, including Roy Wilkins, who expressed the NAACP’s

“profound appreciation” for the attorney general’s forthright stand.

CORE, too, sent a congratulatory note to Attorney General Kennedy. In

truth, though, Farmer and other CORE staff members harbored serious reser-

vations about the tone and content of the speech. They were disappointed that

he had failed to mention CORE or the Freedom Ride. Even more troubling

was his avowed determination “to achieve amicable, voluntary solutions with-

out going to court.” Far too often, in their experience, the word “voluntary”

had served as a code word for foot-dragging noncompliance. For Kennedy to

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 131

say, as he did in the speech, that “the hardest problems of all in law enforce-

ment are those involving a conflict of law and custom” seemed tantamount to

saying that continued segregationist resistance was inevitable and even legiti-

mate. They wanted the Kennedy administration to take an unequivocal stand

on the immediate and uncompromising enforcement of the law. Nothing less

would satisfy the freedom fighters of CORE, especially those who were about

to test the waters of resistance in the Deep South.

The Freedom Riders’ uneasy feeling about the Kennedy administration’s

position on civil rights deepened on Tuesday morning, May 9, when a White

House press release distanced the president from two civil rights bills that he

had previously promised to support. Later the same day, Governor Vandiver

issued a statement claiming that during the recent campaign Senator Kennedy

had promised that his administration would never use federal troops to en-

force desegregation in Georgia. When the expected White House denial

failed to materialize, civil rights leaders began to worry that the Kennedy

brothers were talking out of both sides of their mouths. At the very least, the

Freedom Riders had renewed cause for concern as they said their good-byes

to McCain and boarded the buses to Augusta on the morning of the twelfth.

36

The 120-mile trip from Sumter to Augusta took the Freedom Riders

through the historic midsection of South Carolina—east across the Wataree

River to the capital city of Columbia, then southwest through the heart of

agrarian Lexington and Aiken counties, and finally to the banks of the Savan-

nah River. Along the way, they skirted the edge of notorious Edgefield County—

reputed to be the most violent county in the South, and celebrated in Southern

political lore as the spawning ground of such notables as the antebellum Fire

Eater James Henry Hammond, the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-

century white supremacist demagogue “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, and the 1948

Dixiecrat standard-bearer Strom Thurmond.

37

Though only a short ride from “bloody” Edgefield, Augusta—where the

Freedom Riders were scheduled to spend Friday night—fancied itself as a

genteel enclave epitomizing the finest traditions of the Old South. Situated

on the west bank of the river, the city exuded an aura of stolid confidence

that matched the graceful Victorian homes lining its streets. Augustans, black

and white, seemed to live their lives at an unhurried pace, well within the

confines of a paternalistic ethos. Like most “Old South” communities, the

city had a rough underside that belied the pretense of complacent serenity,

but the Riders did not expect much trouble during their first stop in Georgia.

Earlier in the year the Augusta police had arrested a black soldier for trying

to desegregate one of the city’s terminal lunch counters, but the Riders en-

countered no such resistance at either terminal. Although the black Riders

were the first nonwhites to break the color line at the Augusta bus stations,

no one seemed to care, except for one white waitress who refused to serve

Joe Perkins, forcing a black co-worker to do so. It all seemed too easy, and

later that evening Walter Bergman and Herman Harris, one of the Morris

132 Freedom Riders

College students who had joined the Ride in Sumter, returned to the Trailways

restaurant for a second test. Once again they “were served courteously” and

without incident. One thing the Riders had learned during their first week

on the road was that each community had its own peculiarities where matters

of race and segregation were concerned. Regional and even statewide gener-

alizations, it appeared, were untrustworthy and often misleading. This rev-

elation was not altogether reassuring, since it suggested that the struggle for

civil rights would have to be waged in a bewildering array of settings. But the

variability of Jim Crow culture across time and space certainly added to the

adventure of the Freedom Ride, which was turning out to be far less predict-

able than expected.

38

On Saturday morning, May 13, the Freedom Riders set out for Atlanta

by way of Athens, the college town that had recently hosted Attorney Gen-

eral Kennedy. The surprisingly warm reception accorded to the attorney

general indicated that Athens was a fairly progressive community compared

to Rock Hill or Winnsboro, but as the Freedom Riders pulled into Athens

for a short rest stop, they could not help remembering the news reports of

the ugly scenes that had accompanied the desegregation of the University of

Georgia in January. Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes had gained

admission, but only after braving a mob of angry whites and overcoming the

machinations of university administrators and politicians. To their relief,

the Freedom Riders encountered no such problems when they sat down at

the Athens lunch counter. The terminal staff, as well as the regular passen-

gers, seemed to take everything in stride. Noting that “there were no gapers,”

Peck marveled that “a person viewing the Athens desegregated lunch counter

and waiting room during our fifteen-minute rest stop might have imagined

himself at a rest stop up North rather than deep in Georgia.” Later in the day

the Riders enjoyed a similar episode in Atlanta, leading Peck to conclude

that “our experiences traveling in Georgia were clear proof of how desegre-

gation can come peacefully in a Deep South state, providing there is no de-

liberate incitement to hatred and violence by local or state political leaders.”

Civil rights activists who lived in Georgia knew all too well that this sanguine

observation gave their state far too much credit, but Peck’s appreciation for

the importance of political leadership was clearly on the mark, as events in

Alabama and Mississippi would later confirm.

39

The welcoming scenes at the Atlanta bus stations provided a moving affir-

mation of the civil rights movement’s rising spirit. As the Trailways Riders

stepped off the bus, a large gathering of students—nearly all veterans of lunch

counter sit-ins and picketing campaigns—broke into applause. Rushing for-

ward, the students greeted the road-weary Riders as conquering heroes. Pleased

but a little bit flustered by all of this attention, the Riders, after gathering their

bags, found it impossible to extricate themselves from the throng for a brief

test of the terminal’s facilities. The test would have to wait until their depar-

ture the next morning. There was a similar scene at the Greyhound station,

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 133

though there the Riders managed to test the waiting rooms and restrooms.

Finding the Greyhound restaurant closed, they headed for a row of waiting

cars, which took them to Atlanta University, where they were scheduled to

spend the night. The reception in Atlanta could hardly have been better, though

the Riders were disappointed to learn that Dr. King was in Montgomery at-

tending an SCLC board meeting. Fortunately, he and SCLC executive direc-

tor Wyatt Tee Walker were expected back in Atlanta late in the afternoon.

To the Riders’ delight, King and Walker returned to Atlanta in time to

join them for dinner. Having just received a surprisingly glowing report on

SCLC’s financial situation, King was in a celebratory mood. Accompanied

by several aides, he met the Riders at one of Atlanta’s most popular black-

owned restaurants. This was the first time that the Riders had eaten in a real

restaurant since their “Last Supper” in Washington ten days earlier, and the

belief that King planned to pick up the tab—an assumption that, to Farmer’s

consternation, later proved false—added a festive touch to the occasion.

During the dinner, the SCLC leader was at his gracious best, repeatedly

praising the Freedom Riders for their courage and offering to help in any

way he could. As he listened to the Riders, who one by one related personal

stories of commitment and restraint, he interjected words of encouragement

and reassurances that their behavior represented “nonviolent direct action at

its very best.” He told them that he was proud to serve on the national advi-

sory board of CORE, and before saying good night he made a point of shak-

ing hands with each Rider.

Some of the Riders were so moved by King’s show of support and affec-

tion that they began to hope that he might join them on the bus the follow-

ing morning, but they soon learned that King had no intention of becoming

a Freedom Rider. At one point during the dinner, King privately confided in

Simeon Booker, the reporter covering the Freedom Ride for Jet and Ebony,

warning him that SCLC’s sources had uncovered evidence of a plot to dis-

rupt the Ride with violence. “You will never make it through Alabama,” the

SCLC leader predicted, obviously worried. Booker did his best to laugh off

the threat, facetiously assuring King that he could always hide behind Farmer,

who presented attackers with a large and slow-moving target. Later, when

Booker told Farmer what King had said, he discovered that the CORE leader

had already been apprised of the situation. Unnerved by what he had learned

earlier in the evening, Farmer took both Jimmy McDonald and Genevieve

Hughes aside and tried to convince them to leave the Ride in Atlanta. He did

not want McDonald in Alabama because he did not think he could trust the

young folk singer to remain nonviolent, and he did not want Hughes along

because he feared that the presence of a young white woman might provoke

additional violence among white supremacists obsessed with the threat of

miscegenation. To Farmer’s dismay, both adamantly refused to leave the

Ride, and Hughes even vowed to buy her own ticket to Birmingham if she

had to.

40

134 Freedom Riders

Farmer’s growing sense of apprehension became clear when the Free-

dom Riders gathered for a late-night briefing at their Atlanta University dor-

mitory. The Riders were accustomed to Farmer’s assertive style of leadership,

but they had never seen him quite so solemn or peremptory. He alone would

“lead the testings” for the Trailways group, and Jim Peck would do the same

for the trailing Greyhound group. They were entering “the most ominous

leg of the journey,” and there was no room for error. “Discipline had to be

tight,” he told them, and “strict compliance” with Gandhian philosophy would

have to be maintained. The coming journey through Alabama would pose

daunting challenges, but it would also give them the opportunity to prove to

the world that nonviolent resistance was an idea whose time had come. Surely

this was the time when their rigorous training in nonviolence would pay off.

By the end of the meeting, all of the Riders appeared ready, if not altogether

eager, to face the challenges that awaited them. Huddling together, they linked

arms and sang a few choruses of “We Shall Overcome” before retiring to

their rooms. What dreams and nightmares followed can only be imagined.

41

Later that night, a dormitory counselor awakened Farmer from a deep

sleep. His mother was on the phone, and he rushed down to the first floor to

receive what he knew was bad news. Prior to leaving Washington, he had

paid a tearful visit to his father’s bedside at Freedman’s Hospital. Suffering

from acute diabetes and recovering from a recent cancer operation, James

Farmer Sr. was near death when his son first told him about the Freedom

Ride. Realizing that it was unlikely that he would ever see his son again, the

old man offered his blessing, plus a few words of warning: “Son, I wish you

wouldn’t go. But at the same time, I am more proud than I’ve ever been in

my life, because you are going. Please try to survive. . . . I think you’ll be all

right through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and maybe even

Georgia. But in ’Bama, they will doubtless take a potshot at you. With all my

heart, I hope they miss.” As Farmer’s mother informed him of his father’s

passing, these final words came flooding back to him. He knew that his fa-

ther would want him to finish the Ride, but he also knew that his distraught

mother expected him to return for the funeral. As Farmer later confessed, in

making the choice to return to Washington he had to overcome an almost

unbearable “confusion of emotions.” “There was, of course, the incompa-

rable sorrow and pain,” he recalled. “But, frankly, there was also a sense of

reprieve, for which I hated myself. Like everyone else, I was afraid of what

lay in store for us in Alabama, and now that I was to be spared participation

in it, I was relieved, which embarrassed me to tears.”

During and after the funeral, Pearl Farmer insisted that her husband had

actually “willed the timing of his death” in order to save his son from the

coming ordeal in Alabama. But no explanation, real or imagined, made it any

easier for Farmer to tell his fellow Riders that he was abandoning them. As

they gathered around the breakfast table on Sunday morning, May 14, the

embarrassed and emotionally drained leader stunned his charges with the

Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’ 135

news that his father’s death required him to fly to Washington later in the

morning. He would rejoin the Ride as soon as possible, he assured them,

probably within two or three days. Until then, they could communicate with

him by phone, and Joe Perkins would take over his duties as “captain” of the

Greyhound group. Perkins appreciated Farmer’s vote of confidence, but he—

like most of the Freedom Riders—did not know quite how to respond to

Farmer’s announcement. They could hardly begrudge their grieving leader

the chance to bury his father. After all, it was Mother’s Day, and they couldn’t

help thinking of their own families as Farmer said his good-byes. They were

confident that he would keep his word and rejoin the Ride, but some of the

more nervous Riders weren’t sure what shape they would be in after several

leaderless days in the wilds of Alabama.

42

Farmer was the third Rider to take leave of the group, following John

Lewis and Ben Cox, who was in High Point polishing his Mother’s Day ser-

mon. Lewis had been gone the longest—four days—and a great deal had

happened since his departure. The trip to Philadelphia, his first journey to

the Northeast, was a qualified success. He weathered the American Friends

Service Committee interview with ease and even passed the physical, despite

the cuts and bruises received during the Rock Hill beating. On Friday, while

the other Riders were en route from Sumter to Augusta, he learned that he

had won a fellowship, but the overseas assignment, which would begin in the

late summer, was to India, not to Tanganyika, where he had hoped to ex-

plore his African roots. Though somewhat disappointed, he accepted the

India fellowship, which would allow him to follow in the footsteps of Jim

Lawson—and Gandhi.

On Sunday he caught a plane to Nashville, with the hope that he could

find a ride to Birmingham on Sunday evening. Arriving in Nashville on Satur-

day night, he had just enough time to spend a few hours with Bernard

Lafayette, Jim Bevel, and his other friends in the Nashville Movement. Ear-

lier in the weekend, Nashville’s civil rights leaders had received word that

the city’s white theater owners had agreed to desegregate. For fourteen weeks

the Nashville Movement had applied almost constant pressure in the form of

stand-ins and picketing campaigns, vowing to continue the protests until ev-

ery black activist in the city was in jail if necessary. The theater owners’ sur-

render represented a great victory, and movement leaders planned to celebrate

their triumph with a “big picnic” on Sunday afternoon. Against all odds, Lewis

was there to help his friends celebrate, but not even a victory of this magni-

tude could take his mind off his fellow Freedom Riders for very long. “The

Freedom Ride,” he later confessed, “was once again all I was thinking about.”

43

ALTHOUGH LEWIS DID NOT KNOW IT AT THE TIME, he was not the only person

fixated on the Freedom Ride. While he was in Nashville making plans to

rejoin the Ride, the leaders of the Alabama Knights of the Ku Klux Klan