Alfred DeMaris - Regression with Social Data, Modeling Continuous and Limited Response Variables

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Examining Variable-Specific Interaction Effects

Interactions between specific variables in their effects on the response are best inves-

tigated with cross-product terms. In that the model for the probabilities is already

interactive in the regressors, what is achieved by adding a cross-product if the prob-

ability is our focus? The main advantage is that using a cross-product term allows

interaction effects in the probabilities to be disordinal, whereas without it, the inter-

action is constrained to be ordinal. Recall from Chapter 3 that the descriptors ordi-

nal and disordinal refer to degrees of interaction. When the impact of the focus

variable differs only in magnitude across levels of the moderator, the interaction is

ordinal. If the nature (or direction) of the impact changes over levels of the modera-

tor, the interaction is disordinal. Without a cross-product term, the partial slope of X

k

on the probability is, as noted earlier, β

k

[π(x) (1 ⫺ π(x))]. [I’m using the notation

π(x) here to emphasize that π changes with x.] Because [π(x) (1 ⫺ π(x))] ⱖ 0, the

impact of X

k

on the probability always has the same sign, regardless of the settings

of the X’s in the model (i.e., β

k

[π(x) (1 ⫺ π(x))] takes on whatever sign β

k

takes).

Hence, the effect of X

k

can differ only in magnitude, but not direction, with different

values of the X’s. With a cross-product in the model of the form γX

k

X

j

, however, the

partial slope for X

k

becomes (β

k

⫹ γX

j

) [π(x) (1 ⫺ π(x))]. In this case, because β

k

and

γ could be of opposite signs, the impact of X

k

on the probability could change direc-

tion at different levels of X

j

, producing a disordinal interaction.

The interaction model for the log odds, with two predictors, X and Z,is

ln O ⫽ β

0

⫹ β

1

X ⫹ β

2

Z ⫹ γXZ.

Interpretation is similar to that for the linear regression model, except that in this

case, the response is the log odds of event occurrence. With X as the focus variable,

its effect can be seen by factoring out its common multipliers:

ln O ⫽ β

0

⫹ β

2

Z ⫹ (β

1

⫹ γZ)X.

The impact of X on the odds is therefore exp(β

1

⫹ γZ), or, following the framework

I have previously articulated (DeMaris, 1991), it is exp(β

1

) [exp(γ)]

z

. This last

expression suggests that each unit increase in Z magnifies the impact of X by exp(γ).

Table 8.2 presents logistic regression models for couple violence allowing alcohol/

drug problem to interact with economic disadvantage in their effects on the log odds of

violence. There is solid justification for expecting these factors to interact. The impact

of having an alcohol or drug problem on intimate violence may be exacerbated in dis-

advantaged neighborhoods. Living amidst economic disadvantage is likely to enhance

the stress associated with substance abuse. Additionally, the social isolation and absence

of community monitoring that typically characterizes such neighborhoods may create a

context in which “high” or inebriated partners feel freer to vent their frustrations phys-

ically on one another (Miles-Doan, 1998; Sampson et al., 1997). Similarly, living in a

disadvantaged neighborhood may be more stressful for those with substance abuse

problems.

MODELING INTERACTION 285

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 285

Model 1 in Table 8.2 includes the cross-product of alcohol/drug problem with eco-

nomic disadvantage, the latter being a centered regressor. The effect of alcohol/drug

problem on the log odds of violence is .968 ⫹ .069 economic disadvantage. The effect

on the odds of violence is exp(.968 ⫹ .069 economic disadvantage). Thus, having a

substance abuse problem raises the odds of violence by exp(.968) ⫽ 2.633 for those in

neighborhoods of average economic disadvantage levels. For those a unit higher in

economic disadvantage, the effect of alcohol/drug problem on the odds is exp(.968 ⫹

.069) ⫽ exp(1.037) ⫽ 2.821. Or, the effect of having an alcohol or drug problem is

magnified by a factor of exp(.069) ⫽ 1.071 for each 1-unit increase in economic dis-

advantage [see DeMaris (1991) for additional use of this multiplicative framework for

interpreting interactions]. For those who are a standard deviation (5.128) higher in eco-

nomic disadvantage, the effect of alcohol/drug problem is exp[.968 ⫹ .069(5.128)] ⫽

exp(1.321) ⫽ 3.747. Or, with economic disadvantage as the focus, the impact of

economic disadvantage on the log odds is .016 ⫹ .069 alcohol/drug problem. For

those without substance abuse problems, each unit increase in economic disadvantage

magnifies the odds of violence by a factor of exp(.016) ⫽ 1.016, a nonsignificant effect.

For those with substance abuse problems, the effect is exp(.016 ⫹ .069) ⫽ exp(.085) ⫽

1.089.

Targeted Centering

The significant interaction effect means that the effect of alcohol/drug problem (eco-

nomic disadvantage) changes over levels of economic disadvantage (alcohol/drug

286 ADVANCED TOPICS IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

Table 8.2 Logistic Regression Models for the Interaction between Economic

Disadvantage and Alcohol/Drug Problem in Their Effects on Violence

Predictor Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Intercept ⫺2.148*** ⫺1.180*** ⫺2.065***

Relationship duration ⫺.046*** ⫺.046*** ⫺.046***

Cohabiting .830*** .830*** .830***

Minority couple .216* .216* .216*

Female’s age at union ⫺.027*** ⫺.027*** ⫺.027***

Male’s isolation .021* .021* .021*

Economic disadvantage .016 .085**

Alcohol/drug problem .968*** 1.321***

Alcohol/drug free ⫺.968***

Economic disadvantage ⫺ SD .016

Economic disadvantage .069*

⫻ alcohol/drug problem

Economic disadvantage ⫺.069*

⫻ alcohol/drug Free

Economic Disadvantage ⫺ SD .069*

⫻ alcohol/drug problem

* p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001.

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 286

problem). But is the effect of, say, economic disadvantage significant for those with

alcohol or drug problems? Or, is the effect of alcohol/drug problem significant for

those at, say, 1 standard deviation above mean economic disadvantage? What is

needed is a test for the significance of the focus variable at a particular level of the

moderator. In Chapter 3 I presented a formula for finding the variance of the partial

slope for the impact of X at a particular level, z, of Z. If the estimated partial slope

is written b

1

⫹ gz, the formula for V(b

1

⫹ gz), given by equation (3.10), is

V(b

1

⫹ gz) ⫽ V(b

1

) ⫹ 2z Cov(b

1

, g) ⫹ z

2

V(g).

Here I outline a technique, first introduced in Chapter 6, that I refer to as targeted cen-

tering, which obviates the need to compute such a variance by hand. We simply code

the variables involved in creating the cross-product term so that the effect of interest

is the main effect of one of the variables. To discern whether economic disadvantage

is significant for couples with alcohol or drug problems, we simply recode the dummy

for alcohol/drug problem so that having an alcohol or drug problem is the reference

category. The new dummy is called “alcohol/drug free” in Table 8.2. Then the cross-

product of economic disadvantage with alcohol/drug free is formed to capture the

interaction effect. Model 2 in Table 8.2 shows the results. The main effect on the log

odds of violence of economic disadvantage is now the effect for those with alcohol or

drug problems. The value of .085 agrees with what was shown above for those who

have substance abuse problems. Now we see that the effect of economic disadvantage

is, indeed, significant for this group.

Model 3 shows the effect of applying targeted centering to economic disadvantage.

In that the standard deviation of economic disadvantage is 5.128, “economic disad-

vantage ⫺SD” is economic disadvantage ⫺5.128. [In that the variable is already

centered, economic disadvantage ⫺ (mean ⫹ SD) reduces to economic disadvantage ⫺

SD.] The cross-product of alcohol/drug problem with (economic disadvantage ⫺SD)

is formed and included in the model. Then the effect of alcohol/drug problem is:

1.321 ⫹ .069 (economic disadvantage ⫺SD). For couples whose economic disadvan-

tage is 1 standard deviation above the mean, economic disadvantage ⫺SD equals zero.

Hence, the effect of alcohol/drug problem at 1 standard deviation above mean eco-

nomic disadvantage is just the main effect of alcohol/drug problem, or 1.321, which,

as shown, is very significant. (This effect also agrees with the calculations above.) As

a final note, targeted centering can be employed in any regression equation, linear or

otherwise.

MODELING NONLINEARITY IN THE REGRESSORS

Although the logistic regression model is nonlinear in the regressors with respect to

probabilities, it is assumed to be linear in the log odds. However, this may not be

a reasonable assumption. For example, in the case of couple violence, it might be

expected that the log odds of couple violence would initially drop markedly with

increasing relationship duration. Couples are likely to learn to use more constructive

MODELING NONLINEARITY IN THE REGRESSORS 287

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 287

conflict-resolution techniques in their relationships over time and should become

less likely to be violent as they spend a longer time together. Violent couples are also

more likely to dissolve their relationships, so over time, we expect only the better-

adjusted couples to stay together. Nevertheless, beyond a certain relationship dura-

tion, increasing duration would not be expected to keep having a beneficial effect on

inhibiting violence. Rather, the effect of increasing duration should lessen in magni-

tude for couples who have been together for a long time. Although such a trend

might be fitted with a quadratic term, we begin without assuming any particular

parametric form that a nonlinear trend might take.

Testing for Nonlinearity

We can explore whether there is nonlinearity in the relationship between the log odds

and a continuous regressor using a technique suggested by Hosmer and Lemeshow

(2000). They recommend partitioning a continuous regressor into quartiles or quintiles

of its sample distribution. That is, for a continuous regressor, X, and using quintiles, we

recode X so that the value 1 represents the 20% of the sample with the lowest scores

on X, the value 2 represents the 20% of the sample with the next-lowest scores on X,

and so on, until finally, the value 5 represents the 20% of the sample with the highest

scores on X. We then dummy up the quintiles and examine the relationship between

the log odds of event occurrence and the quintile dummies, while controlling for other

model effects. Table 8.3 shows this technique applied to relationship duration.

288 ADVANCED TOPICS IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

Table 8.3 Models Investigating the Nonlinear Effect of Relationship Duration on the

Log Odds of Violence

Predictor Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Intercept ⫺1.529*** ⫺1.027*** ⫺2.310*** ⫺2.837***

Cohabiting .759** .773** .769** .679**

Minority couple .244* .247* .242* .242*

Female’s age at union ⫺.028*** ⫺.028*** ⫺.029*** ⫺.029***

Male’s isolation .021* .021** .021** .021**

Economic disadvantage .023* .023* .023* .023*

Alcohol/drug problem 1.036*** 1.030*** 1.040*** 1.040***

Duration quintile 2 ⫺.059

Duration quintile 3 ⫺.493***

Duration quintile 4 ⫺1.211***

Duration quintile 5 ⫺1.349***

Duration quintile ⫺.371***

Relationship duration ⫺.054***

(Relationship duration)

2

.001**

Relationship duration ⫺ SD ⫺.029***

(Relationship Duration ⫺ SD)

2

.001**

Model χ

2

207.054*** 196.495*** 204.127*** 204.127***

df 10 7 8 8

* p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001.

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 288

Model 1 presents the regression of the log odds of couple violence on the covari-

ates in Table 8.1, with relationship duration quintiles 2 to 5 represented as dummies.

The lowest quintile of relationship duration is the reference category. The dummy

coefficients indicate that the reduction in the log odds of violence associated with

quintiles 4 and 5 is substantially larger than the reductions associated with quintiles 2

and 3, suggesting a nonlinear trend. However, to observe this trend more readily, we

can plot the relationship between the log odds of violence and duration quintile, con-

trolling for the other covariates. This is accomplished simply by using the dummies

and the intercept to estimate the log odds for each quintile. That is, for married, non-

minority, alcohol- and drug-free couples at average female age at union, male isola-

tion,and economic disadvantage, the estimated log odds of violence is ⫺1.529 for

those in the lowest duration quintile. For comparable couples in the second quintile,

the log odds is ⫺1.529 ⫺ .059 ⫽⫺1.588. For comparable couples in the third quin-

tile, the log odds is ⫺1.529 ⫺ .493 ⫽⫺2.022, and so on. The last two log odds are

⫺2.74 and ⫺2.878. These values are then plotted against duration quintile, whose

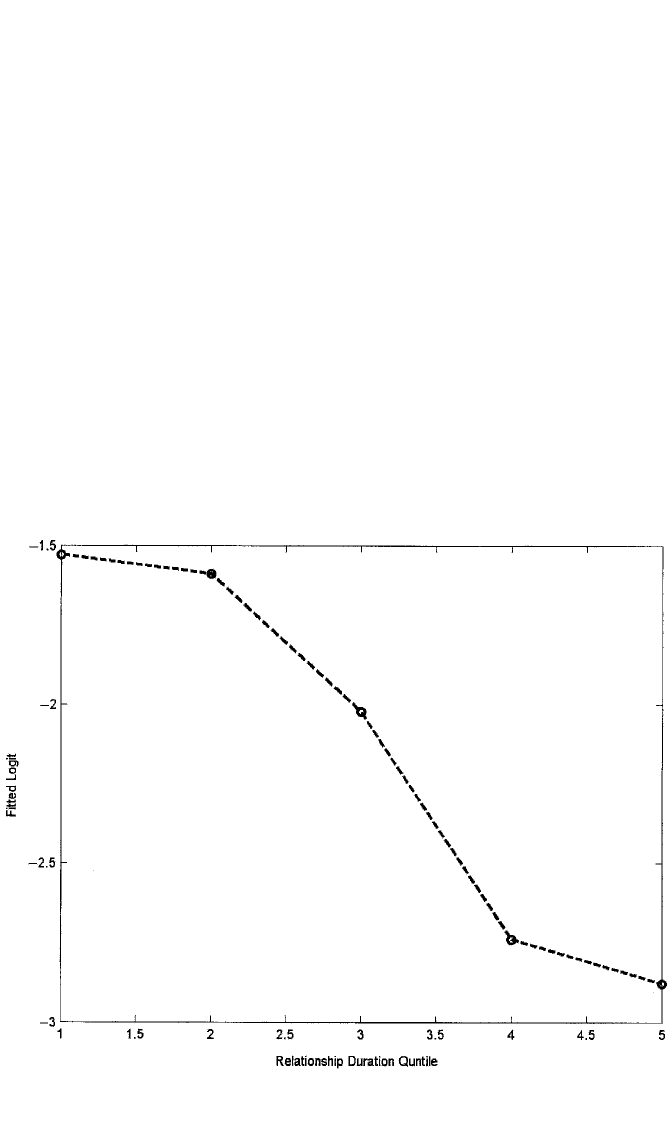

values range from 1 through 5. The result is shown in Figure 8.1.

The plot suggests, as suspected, that the logit of violence declines with increasing

duration until quintile 4, at which point it levels off. This type of trend can be cap-

tured nicely with a quadratic term. However, there is also the suggestion that the

MODELING NONLINEARITY IN THE REGRESSORS 289

Figure 8.1 Plot of log odds of violence against relationship duration quintile, based on model 1 in

Table 8.3.

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 289

decline begins gradually and then accelerates between quintiles 2 and 4 before it lev-

els off. That is, the entire curve actually appears to have three bends, suggesting that

perhaps a cubic polynomial in relationship duration would provide a good fit. Never-

theless, we first need to test whether the trend in relationship duration is significantly

nonlinear. For this purpose, we can test model 1 in Table 8.3 against model 2,

which includes duration quintile, coded 1 to 5, modeled as a linear effect. The test sta-

tistic is χ

2

⫽ 207.054 ⫺ 196.495 ⫽ 10.559. The test has 3 degrees of freedom and is

significant at p ⫽ .014. I conclude that the relationship between the log odds of

violence and relationship duration is not linear. To model the trend in Figure 8.1,

I elected to include both duration-squared and duration-cubed in the model, in addi-

tion to duration, all using the original continuous coding. For this purpose, relation-

ship duration is first centered, thus minimizing collinearity problems in the estimates

due to higher-order terms. It turns out that the cubic term was not significant (results

not shown) but the quadratic term was. So I chose the quadratic model as best cap-

turing the nonlinearity in relationship duration. The results are shown as model 3 in

Table 8.3.

Targeted Centering in Quadratic Models

The estimates in model 3 suggest that the partial slope for relationship duration is

⫺.054 ⫹ 2(.001) relationship duration. The implication is that relationship duration

reduces the log odds of violence, but at a declining rate the longer couples have already

been together. That is, the effect of an instantaneous increase in relationship duration

depends on the value of relationship duration. The main effect of relationship dura-

tion, ⫺.054, is the partial slope (or partial derivative) of duration at mean duration,

which is 14.9 years. This is clearly significant. What about the effect at a standard devi-

ation above the mean? The unrounded estimates for duration and duration-squared are

actually ⫺.0535 and .000968, respectively, and a standard deviation of relationship

duration is 12.8226 years. The effect is, therefore, ⫺.0535 ⫹ 2(.000968) (12.8226) ⫽

⫺.0287, or ⫺.029. To assess whether this effect is significant, we would normally want

to calculate its standard error using covariance algebra. Letting X represent relation-

ship duration, the estimated partial slope can be denoted b ⫹ 2gx. Its variance is (as the

reader can verify with covariance algebra)

V(b ⫹ 2gx) ⫽ V(b) ⫹ 4x Cov(b,g) ⫹ 4x

2

V(g).

Once again, however, we can use targeted centering to avoid computation of the

standard error by hand. In this case, we simply create a new “centered” variable, rela-

tionship duration ⫺ 12.8226, shown as “relationship duration ⫺ SD” in Table 8.3,

along with its square, (relationship duration ⫺ SD)

2

, and use these in the model to

capture the effect of relationship duration. The results are shown in model 4 in Table

8.3. The partial slope of relationship duration is now ⫺.029 ⫹ 2(.001) (relationship

duration ⫺ SD). When relationship duration is at 1 standard deviation above the

mean, (relationship duration ⫺ SD) equals zero, and the effect is ⫺.029, as calculated

above. As is evident, this effect is also quite significant.

290 ADVANCED TOPICS IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 290

TESTING COEFFICIENT CHANGES IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

In Chapter 3 we saw that we could test for the significance of changes in coefficient val-

ues across nested linear regression models using the procedure outlined by Clogg et al.

(1995). In the same article, the authors detailed the procedure for testing coefficient

changes in any form of the generalized linear model. Here, I discuss that procedure in

the context of logistic regression. As an example, Table 8.4 presents two models for cou-

ple violence. Model 1 represents the results of refinements in this chapter, with respect

to interaction and nonlinear effects, made to the base model of Chapter 7. It is essen-

tially the logit model from Table 7.1 to which have been added the quadratic effect of

relationship duration, plus the interaction between economic disadvantage and alco-

hol/drug problem. The model suggests that a number of factors affect the log odds of

couple violence. Of interest, however, are the mechanisms responsible for these effects.

Why, for example, do substance abuse problems elevate the odds of violence? One

possible explanation is that alcohol and drugs promote relationship dissension, par-

ticularly of a more hostile nature (Leonard and Senchak, 1996). Arguments may erupt

over a partner’s drinking or drug use. Or, the substance-abusing partner may, under

the influence of alcohol or drugs, become more belligerent than he or she normally

would. At any rate, I suggest that part of the effect of substance abuse on violence is

due to its tendency to increase hostile argumentation, which, in turn, elevates the risk

of violence. Similar arguments could be made for the other predictors. Each may

affect the risk of violence because it elevates the level of hostile argumentation in the

TESTING COEFFICIENT CHANGES IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION 291

Table 8.4 Comparing Coefficients for Focus Variables before vs. after Adding Conflict

Management Mediators

Predictor Model 1 Model 2

δ

ˆ

z for

δ

ˆ

Intercept ⫺2.308*** ⫺2.553***

Cohabiting .789** .867*** ⫺.077 ⫺2.745

Minority couple .238* .206 .031 3.109

Female’s age at union ⫺.030*** ⫺.016 ⫺.014 ⫺14.004

Male’s isolation .021** .013 .008 16.062

Economic disadvantage .016 .014 .002 1.638

Alcohol/drug problem .978*** .654*** .323 18.417

Relationship duration ⫺.054*** ⫺.052*** ⫺.001 ⫺2.089

(Relationship duration)

2

.00098** .0015*** ⫺.0005 ⫺21.873

Economic disadvantage .070* .061* .009 1.719

⫻ alcohol/drug problem

Open disagreement .064***

Positive communication ⫺.441***

Model χ

2

210.319*** 453.310***

df 911

Hosmer–Lemeshow χ

2

(8) 12.470

R

2

MZ

.239

∆

ˆ

.131

* p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001.

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 291

relationship. Model 2 explores this possibility by adding two measures of relationship

dissension. Open disagreement taps the frequency of open disagreements, and posi-

tive communication is a scale that measures the extent to which disagreements are

conducted calmly. It is evident that the effect of alcohol/drug problem (at mean eco-

nomic disadvantage), as well as the effects of several other factors (e.g., female’s age

at union, male’s isolation) have been noticeably reduced after controlling for these

measures of verbal conflict. However, are these coefficient changes significant?

Variance–Covariance Matrix of Coefficient Differences

In general, the test for the significance of coefficient changes in logistic regression is

as follows. Once again, we define a baseline model with p parameters as

ln O ⫽ α ⫹ 冱β

p

*

X

p

,

whereas the full model with q added parameters is:

ln O ⫽ α ⫹ 冱β

p

X

p

⫹ 冱γ

q

Z

q

.

We are interested in whether the β

k

*

, the coefficients of the focus variables in the

baseline model, are significantly different than the β

k

, the coefficients of the same

focus variables in the full model, after the other variables (the Z

1

, Z

2

,...,Z

q

) have

been included. Therefore, we wish to test whether the coefficient differences, δ

k

⫽

β

k

*

⫺ β

k

, for k ⫽ 1,2,...,p,are different from zero. Under the assumption that the

full model is the true model that generated the data, the statistic d

k

/σ

ˆ

d

k

(where d

k

⫽

b

k

*

⫺ b

k

is the sample difference in the kth coefficient and σ

ˆ

d

k

is the estimated stan-

dard error of the difference) is distributed asymptotically as standard normal (i.e., it

is a z test) under H

0

: δ

k

⫽ 0 (Clogg et al., 1995).

Unfortunately, the standard errors of the d

k

are not a standard feature of logistic

regression software. However, they can be recovered via a relatively straightforward

matrix expression. If we let V(

δδ

ˆ

) represent the estimated variance–covariance matrix

of the coefficient differences, the formula for this matrix is

V(

δδ

ˆ

) ⫽ V(

ββ

ˆ

) ⫹ V(

ββ

ˆ

*)[V(

ββ

ˆ

)]

⫺1

V(

ββ

ˆ

*) ⫺ 2V(

ββ

ˆ

*),

where V(

ββ

ˆ

) is the sample variance–covariance matrix for the b

k

’s in the full model,

V(

ββ

ˆ

*) is the sample variance–covariance matrix for the b

k

*

’s in the reduced model,

and [V(

ββ

ˆ

)]

⫺1

is the inverse of the variance–covariance matrix for the b

k

’s in the full

model (Clogg et al., 1995). [A copy of an SAS program that estimates the reduced

and full models, computes V(

δδ

ˆ

), and produces z tests for coefficient changes across

models is available on request from the author.]

The third column of Table 8.4 shows the coefficient changes for all variables in

model 1 after open disagreement and positive communication have been added. Column

4 shows the z tests for the significance of the changes. We see that all changes are quite

significant except those for the effects of economic disadvantage and the interaction of

292 ADVANCED TOPICS IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:54 PM Page 292

economic disadvantage with alcohol /drug problem. In particular, part of the effect of

alcohol/drug problem (at mean economic disadvantage) appears to be mediated by

open disagreement and positive communication. A final comment before closing this

section: The reader will notice that even relatively small coefficient changes across

models turn out to be significant. The standard errors of the coefficient changes tend to

be quite small in this test, primarily because coefficients for the same regressors in base-

line and full models are not independent (Clogg et al., 1995). As in other such scenar-

ios involving dependent samples (e.g., the paired t test) standard errors of differences

between dependent estimates tend to be smaller, inflating the values of test statistics.

Discriminatory Power and Empirical Consistency of Model 2

We saw in Chapter 7 that the base logit model in Table 7.1 was not quite empiri-

cally consistent, according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic. Nor did it have

impressive discriminatory power, according to either the explained-variance or

ROC criteria. However, that model was missing some important effects, which,

hopefully, have been incorporated into model 2 in Table 8.4. Reassessing empirical

consistency and discriminatory power for this model produced the following

results, shown at the bottom of the model 2 column. The Hosmer–Lemeshow sta-

tistic is 12.47, which, with 8 degrees of freedom, is no longer significant (p ⫽ .13).

The model now appears to be empirically consistent or to have an adequate fit.

About 24% of the variance in the underlying physical aggression scale is now

accounted for by the model. Or, the model explains about 13% of the risk of vio-

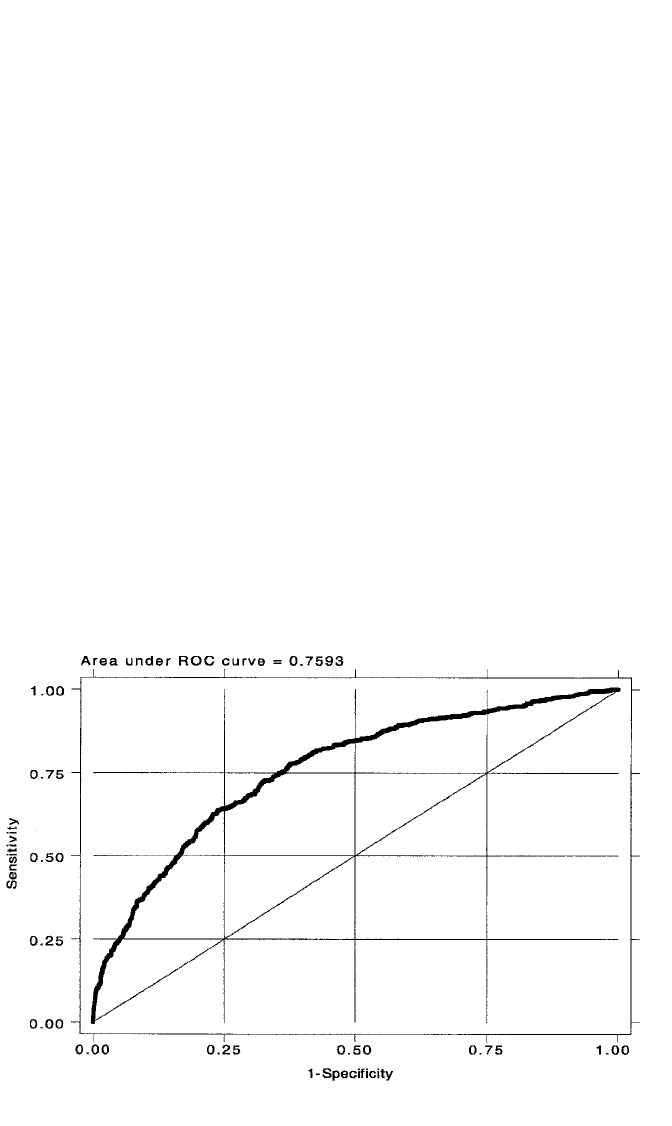

lence. The ROC for model 2 is shown in Figure 8.2. As is evident, the area under

TESTING COEFFICIENT CHANGES IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION 293

Figure 8.2 Receiver operating characteristic curve for model 2 in Table 8.4.

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:55 PM Page 293

the curve is now .7593, which, according to the guidelines articulated in Chapter 7,

represents acceptable discriminatory power.

MULTINOMIAL MODELS

Response variables may consist of more than two values but still not be appropriate

for linear regression. Unordered categorical, or nominal, variables are those in which

the different values cannot be rank ordered. Ordered categorical variables have val-

ues that represent rank order on some dimension, but there are not enough values to

treat the variable as continuous (e.g., there are fewer than, say, five levels of the vari-

able). Logistic regression models are easily adaptable to these situations and are

addressed in this section of the chapter.

Unordered Categorical Variables

Until now I have been treating intimate violence as a unitary phenomenon. However,

in that violence by males typically has graver consequences than violence by females

(Johnson, 1995; Morse, 1995) it may be important to make finer distinctions. For this

reason, I distinguish between two types of violence in couples. I refer to the first as

“intense male violence,” which reflects any one of the following scenarios: The male

is the only violent partner, both are violent but he is violent more often, or both are vio-

lent but only the female is injured. All other manifestations of violence are referred to

as “physical aggression.” Both types of violence are contrasted with “nonviolence” (or,

more accurately, “the absence of reported violence”), the third category of the response

variable that I term couple violence profile. Of interest now is the degree to which the

final model for violence, model 2 in Table 8.4, discriminates among “intense male vio-

lence,” “physical aggression,” and “nonviolence.” I begin by treating couple violence

profile as unordered categorical. That is, these three levels are treated as qualitatively

different types of intimate violence (or the lack of it). However, it can be argued that

they represent increasing degrees of violence severity, with “intense male violence”

being more severe than “physical aggression,” which is obviously more severe than

“nonviolence.” In a later section, these three categories are therefore treated as ordered.

Of the 4095 couples in the current example, 3540, or 86.4%, are “nonviolent”;

406, or 9.9%, have experienced “physical aggression”; and 149, or 3.6%, are char-

acterized by “intense male violence.” There are three possible nonredundant odds

that can be formed to contrast these three categories. Each of these is conditional on

being in one of two categories of couple violence profile (Theil, 1970). For example,

there are 3946 couples who experienced either “nonviolence” or “physical aggres-

sion.” Given location in one of these two categories, the odds of “physical aggres-

sion” is 406/3540 ⫽ .115. This odds is also the ratio of the probability of “physical

aggression” to the probability of “nonviolence,” or .099/.864 ⫽ .115. Similarly, given

that a couple is characterized by either “nonviolence” or “intense male violence,” the

odds of “intense male violence” is 149/3540 (⫽ .036/.864) ⫽ .042. Only two of the

odds are independent: once they are recovered, the third is just the ratio of the first

294 ADVANCED TOPICS IN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

c08.qxd 8/27/2004 2:55 PM Page 294