Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

44 1 Introduction

Table 1.8 Greenberg’s (1987) classification of the languages of the Andes

I. C. Hokan 5. Yurumangui.

III. - A. Chibchan 3. Nuclear Chibchan: a. Antioquia (incl.

Katio, Nutabe). b. Aruak (incl.

Guamaca and Kagaba). c. Chibcha

(incl. Duit and Tunebo) d. Cuna.

f. Malibu (incl. Chimila). h. Motilon.

B. Paezan 1. Allentiac (incl. Millcayac).

2. Atacama. 3. Betoi. 4. Chimu.

5. Itonama. 6. Jirajara. 8. Nuclear

Paezan: a. Andaqui. b. Barbacoa (incl.

Cara, Cayapa, Colorado and Cuaiquer).

c. Choco. d. Paez (incl. Guambiano).

IV. A. Aymara Aymara, Jaqaru.

B. Itucale–Sabela 1. Itucale. 2. Mayna. 3. Sabela.

C. Kahuapana–Zaparo 1. Kahuapana (incl. Jebero and

Chayahuita). 2. Zaparo (incl. Arabela

and Iquito).

D. Northern 1. Catacao. 2. Cholona (incl. Hibito).

3. Culli. 4. Leco. 5. Sechura.

E. Quechua.

F. Southern 1. Alakaluf. 2. Araucanian. 3. Gennaken

(=G¨un¨una K¨une). 4. Patagon (incl.

Ona). 5. Yamana.

V. – A. Macro-Tucanoan 1. Auixiri. 2. Canichana. 10. Mobima.

11. Muniche. 15. Puinave. 17. Ticuna–

Yuri: a. Ticuna. b. Yuri. 18. Tucano.

B. Equatorial 1. Macro-Arawakan: a. Guahibo.

c. Otomaco. d. Tinigua. e. Arawakan:

(i) Arawa. (ii) Maipuran (incl.

Amuesha, Apolista, Chamicuro,

Res´ıgaro and the Harakmbut

languages). (iii) Chapacura.

(iv) Guamo. (v) Uro (incl. Puquina and

Callahuaya). 2. Cayuvava. 3. Coche

(=Kams´a). 4. Jibaro–Kandoshi:

a. Cofan. b. Esmeralda. c. Jibaro.

d. Kandoshi. e. Yaruro. 5. Kariri–Tupi:

b. Tupi. 6. Piaroa (incl. Saliba).

8. Timote. 11. Yuracare. 12. Zamuco.

VI. –– A. Macro-Carib 1. Andoke. 2. Bora–Uitoto: a. Bora.

b. Uitoto. 3. Carib. 5. Yagua.

B. Macro-Panoan 1. Charruan. 2. Lengua. 3. Lule–Vilela:

a. Lule. b. Vilela. 4. Mataco–Guaicuru:

a. Guaicuru. b. Mataco. 5. Moseten.

6. Pano–Tacana: a. Panoan. b. Tacanan.

C. Macro-Ge 1. Bororo. 4. Chiquito. 7. Ge–Kaingan:

a. Kaingan. 8. Guato.

1.7 Genetic relations of South American Indian languages 45

names are occasionally added, preceded by an equals sign (=)inorder to ease identi-

fication. The lowest level of the classification is left out because not all the language

names listed in Greenberg’s classification actually represent different languages but,

rather, dialects or different designations of the same language. In other cases, however,

they do represent different languages, a fact which may give rise to confusion.

2

The Chibcha Sphere

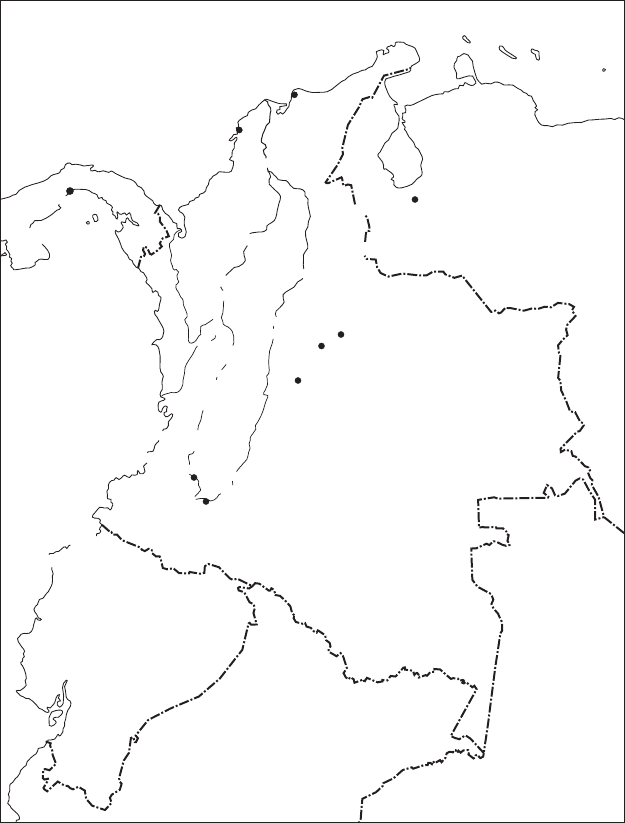

The present chapter deals with the languages of the northern Andes; the term ‘Chibcha

Sphere’ has been chosen because of the historically important role of the Chibcha people

in that area. In the sixteenth century the Chibcha or Muisca were the inhabitants of the

highland region that coincides with the modern Colombian departments of Boyac´a and

Cundinamarca. Although historical sources insist that there was no linguistic unity, it

is likely that most Chibcha spoke closely related languages or dialects belonging to a

subgroup of the Chibchan language family. At least two languages have been identified:

Muisca was spoken on the upland plain (sabana) surrounding the present-day Colombian

capital Santaf´edeBogot´a (department of Cundinamarca) and Duit in the department

of Boyac´a. By their location in the highlands east of the Magdalena river valley, close

to the Amazonian plains, the Chibcha held a peripheral position in the Colombian

Andes. Therefore, their linguistic influence on other parts of that area must not be

overestimated.

The Chibcha were a populous agricultural nation, who specialised in the cultivation of

potatoes and cotton. They were divided into several chiefdoms, two of which occupied a

leading position. A southern chiefdom, centred in Bacat´a or Muequet´a (near the modern

town of Funza, close to present-day Bogot´a), was ruled by a king called the zipa.At

the time of the arrival of the conquistador Gonzalo Jim´enez de Quesada in 1537, the

valley of Bogot´awas filled with a multitude of high wooden buildings, which impressed

the Spaniards so much that they gave it the name of Valle de los Alcazares (‘Valley

of the Castles’). The zipa’s northern neighbour, located in Hunza (today’s Tunja, the

capital of the Boyac´a department), was known as the zaque.Athird town of importance

wasSogamoso (Sugamuxi), the religious centre of the Chibcha and the seat of a highly

venerated wooden temple of huge dimensions. According to tradition, the temple of

Sogamoso was burned down accidentally by two greedy Spanish conquistadores,who

let go of their torches as they beheld the richness of the gold decorations inside (Hemming

1978: 86–7). The high priest of Sogamoso subsequently changed his name to don Alonso

and became one of the most faithful propagandists of the Christian faith (Triana y

Antorveza 1987: 555).

2 The Chibcha Sphere 47

Santa Marta

ACHAGUA

AGATANO

Mérida

GUAMO

SÁLIBA

BETOI

LACHE

OTOMACO

HACARITAMA

CHITARERO

Bogotá

SUTAGAO

COLOMBIA

CUICA

GUANE

OPÓN-CARARE

CATÍO

NUTABE

YAMESÍ

SINÚ

GUACA-

NORI

CUNA

DUIT

Sogamoso

Tunja

TEGUA

MUISCA

MUZO

ARMA-

POZO

Cartagena

PACABUEY

MALIBÚ

ARHUACO

VENEZUELA

MAIPURE

PÁEZ

TIMANÁ

YALCÓN

San Agustín

IRRA

ANSERMA

QUIMBAYA

QUINDÍO

LILI

IDABAEZ

YURUMANGUÍ

JAMUNDÍ

JITIRIJITI

PUBENZA

Popayán

BARBACOA

SINDAGUA

QUILLACINGA

PASTO

SIONA

QUIJO

PERU

ECUADOR

CARA

YUMBO

ESMERALDEÑO

MALABA

NIGUA

PANAMA

A

t

r

a

t

o

R

.

M

a

g

d

a

l

e

n

a

R

.

C

U

E

V

A

T

I

M

O

T

E

G

A

Y

Ó

N

A

Y

A

M

Á

N

J

I

R

A

J

A

R

A

C

A

Q

U

E

T

Í

O

Panamá

M

O

C

A

N

A

C

H

I

M

I

L

A

Y

A

R

I

G

U

Í

M

O

T

I

L

O

N

E

S

C

a

u

c

a

R

.

TA

I

R

O

N

A

G

U

A

J

I

R

O

C

H

O

C

Ó

S.

J

u

a

n

R

.

C

H

A

N

C

O

S

P

I

J

A

O

P

A

N

C

H

E

B

R

A

Z

I

L

C

H

O

N

O

G

U

A

N

A

C

A

A

N

D

A

Q

U

Í

TAMA

P

A

N

T

Á

G

O

R

A

C

O

L

I

M

A

Map 1 The Chibcha Sphere: overview of ethnolinguistic groups attested in premodern sources

The Chibcha heartland also became known worldwide as the source of the El Dorado

legend, a major incentive for conquest and exploration in the northern Amazon. At

regular intervals, the cacique or chieftain of Guatavita, one of the most influential vassals

of the zipa,would anoint himself with gold dust and plunge into a volcanic lake. The

48 2 The Chibcha Sphere

story of El Dorado had a tremendous impact on Spanish conquistadores and adventurers.

During the decades following the conquest, they would organise numerous expeditions

geared at finding other El Dorados. These expeditions brought considerable havoc and

misery to the Chibcha and their neighbours. Their damage in terms of human losses and

social disruption was such that the emperor Charles V forbade all such expeditions in

1550 (Hemming 1978: 139).

There were some remarkable cultural achievements, such as the goldsmith’s art of

the Quimbaya people of the Cauca river valley, the monumental stone sculptures of San

Agust´ın in the department of Huila, the Ciudad Perdida (‘lost city’) of the Tairona in

the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and the pictographic writing system of the Cuna (cf.

Nordenski¨old 1928–30). At the same time, the native peoples of the northern Andes were

divided. Apart from the powerful Muisca kingdoms, there was no political unity, but

rather a conglomerate of small chiefdoms and tribes, living in an almost permanent state

of war. These small political units were usually referred to as behetr´ıas by the Spaniards

(see, for instance, Cieza de Le´on 1553; Acosta 1590). The difference in this respect

between New Granada, as Colombia was called in colonial times, and Peru (including

present-day Ecuador) was emphasised by most of the chroniclers. The Chibcha, although

highly organised internally, were besieged by the warlike tribes of the Magdalena valley,

including the Panche, the Pant´agora and the Pijao, who blocked their way to the west

and contributed to their isolation. Within the neighbouring highlands, the Muzo and the

Colima were encroaching upon the Chibcha heartland from the northwest. A special

caste of warriors, the guecha (probably g¨uecha [wet

y

a]; cf. Uricoechea 1871: 253) were

in charge of the defence of the Chibcha realm, which is otherwise described as relatively

peaceful.

After the arrival of the Spaniards, many Colombian tribes refused to submit and

continued to fight the colonial rulers, taking advantage of the rugged physiognomy of

the country. Famous is the story, possibly a legend, of la Gaitana,afemale cacique of

Timan´ainthe Upper Magdalena valley. In 1543 she is said to have hunted down and

ferociously killed the Spanish conquistador Pedro de A˜nasco, who was responsible for

burning her son.

1

Many sectors of the Magdalena river valley remained dangerous and

insecure for travellers well into the twentieth century. The Chimila, who inhabited the

region east of the lower Magdalena valley (departments of Cesar and Magdalena) and the

Andaqu´ıofthe forest region east of San Agust´ın (departments of Huila and Caquet´a), are

known for their long and tenacious resistance. The fearsome Pijao of Huila and Tolima

challenged Spanish rule in a large-scale rebellion in the early seventeenth century.

1

The story of La Gaitana is related by the chroniclers Juan de Castellanos (1589) and Pedro Sim´on

(1625). Her ethnic background has not been established. She may have belonged either to the

P´aez or to the local Yalc´on nation.

2 The Chibcha Sphere 49

Outside the Chibcha heartland, another concentration of highly developed and popu-

lous societies was found in the valley of the Cauca river, in the modern departments of

Caldas, Risaralda and Quind´ıo. An outstanding position was occupied by the Quimbaya

federation, centred around the modern towns of Chinchin´a (near Manizales) and Pereira

(Chaves, Morales and Calle 1995: 156). The Quimbaya are known as the most talented

goldsmiths of pre-Columbian America. Although the first contacts with the Spanish

conquistador Jorge Robledo in 1539 were not particularly hostile, the subsequent re-

pression and exploitation by Sebasti´an de Belalc´azar and his men from Peru led to a

series of rebellions, which brought about the near annihilation of the Cauca peoples. The

Quimbaya became extinct as a recognisable group around 1700 (Duque G´omez 1970).

Their language remains unknown and its affiliations a matter of speculation.

Sixteenth-century chroniclers report the existence of almost innumerable different

languages. Some of them give a fair account of the situation which can help to make us

aware of the loss. Pascual de Andagoya (1545) mentions the Atunceta, Ciaman, Jitirijiti

and Lili languages spoken in the area of Cali and Popay´an. Only the names of these

languages have been preserved, as well as the observation that they were so different

from each other that the use of interpreters was required. Pedro de Cieza de Le´on

(1553), the chronicler of Peru, who accompanied Captain Robledo in his conquest of

the lower and middle Cauca valley, has left very precise information about the language

situation of Antioquia, Caldas, Quind´ıo and Risaralda. Through an analysis of Cieza’s

linguistic observations, Jij´on y Caama˜no (1938: Appendix, pp. 109–12) points at the

existence of four different languages in the Caldas–Quind´ıo–Risaralda region: Arma–

Pozo, Quimbaya–Carrapa–Picara–Paucura, Quind´ıo and Irra. However, this enumeration

does not include the languages of the Anserma, of the Chancos nation and of several

other local groups. They may either have been separate languages, or be included in

one of the groupings just mentioned. The information on all these languages is too

limited to permit any conclusion as to their genetic affiliation. An exception are the

languages of Antioquia (known as Old Cat´ıo and Nutabe), which were identified as

Chibchan (Rivet 1943–6; Constenla Uma˜na 1991: 31). Interestingly, one of the few

words mentioned by Cieza de Le´on for the language spoken in the towns of Arma and

Pozo (department of Caldas) is ume ‘woman’, which corresponds to ome in the Cuna

language of the Colombian and Panamanian Caribbean coast. A frequent ending -racua

is reminiscent of the Cuna derivational ending -k

w

a (cf. Llerena Villalobos 1987: 72–3).

Such similarities, as well as some others, were observed by Rivet (1943–6) but remain

merely suggestive as long as no additional data are found concerning the languages of

the Cauca valley.

Since most of the indigenous languages were lost without possibility of recovery,

the extent of linguistic variety in the northern Andes may never be fully appreci-

ated. The few languages that have survived the contact with the European invaders may or

50 2 The Chibcha Sphere

may not be representative. As it stands, none of the original languages of the Cauca

and Magdalena valleys have survived, and there is hardly any documentation on them.

The main languages of the sabana, Muisca and Duit, became extinct in the eighteenth

century, although in the first case the available documentation is relatively extensive. On

the other hand, some surviving groups (e.g. the Chocoan Ember´a, the Cuna, the P´aez)

have been remarkably expansive in recent times. From this perspective, the original

linguistic situation and the present-day one are hardly comparable.

2.1 The language groups and their distribution

Colombia and western Venezuela form the northernmost section of the Andean region.

This area was a meeting point of linguistic and cultural influences from the central

Andes, the Amazon basin, the Caribbean and Central America. From an archaeological

and cultural point of view, it is part of a region often referred to as the ‘Intermediate Area’

(Area Intermedia), negatively defined as an area belonging neither to Mesoamerica, nor to

the Central Andean civilisation domain. In addition to Colombia and western Venezuela,

the Intermediate Area also comprises a substantial part of Central America. The linguistic

features of the Intermediate Area have been studied by Constenla Uma˜na (1991), who

finds it subdivided into three main typological regions: a Central American–Northern

Colombian area (including the Cof´an language isolate as an outlier), an Ecuadorian–

Southern Colombian area, and a Guajiro–Western Venezuelan area.

Two important language families, Cariban and Chibchan,have left their mark in the

northern Andes since precontact times. Cariban has its origin in the Amazonian and

Guyanese regions, whereas Chibchan has Central American connections. Considering

their distribution and the amount of internal differentiation within the area under dis-

cussion, the intrusion of the Chibchan languages in the northern Andes is clearly much

older than that of the Cariban languages. Nevertheless, a Central American origin for

the Chibchan languages seems likely because some of the most fundamental diversity

internal to the family is found in Costa Rica and western Panama (Constenla Uma˜na

1990). Furthermore, the closest presumable relatives of the Chibchan family as a whole,

Lenca and Misumalpa, are located at the northern, Central American borders of the

Chibchan domain (Constenla Uma˜na 1991).

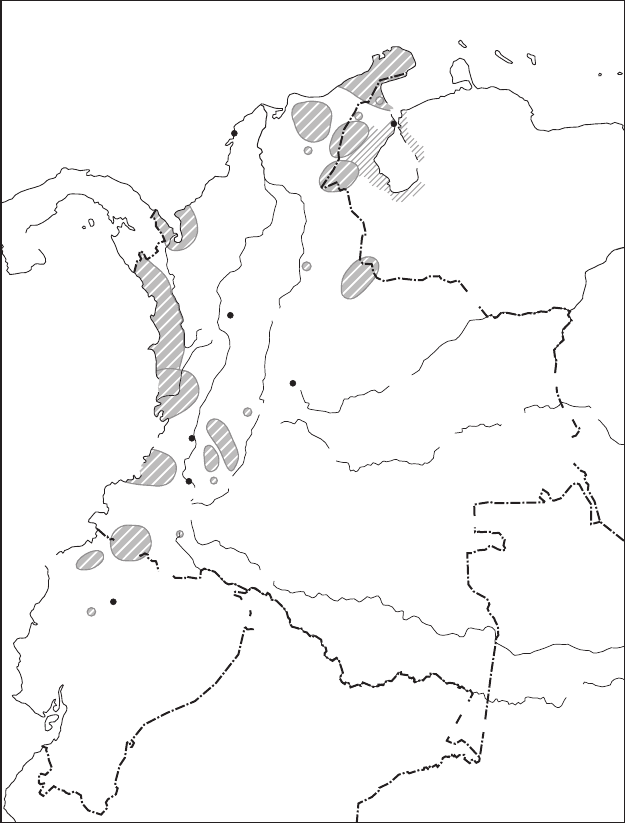

The area of the Caribbean coast of Colombia comprises two important nuclei of

Chibchan-speaking populations: the Cuna, around the Gulf of Urab´a and adjacent

areas of (Atlantic) Panama, at one end, and the complex of indigenous peoples of

the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Ika, Kankuamo, Kogui and Wiwa) and the Sierra

de Perij´a(Bar´ı), at the other. Between these two geographical extremes, several other

groups were decimated or eliminated early in the colonial process. In the present-day

departments of Bol´ıvar, C´ordoba and Sucre, three prosperous chiefdoms, Fincen´u,

Pancen´u and Cen´ufana represented the Sin´u culture, renowned for its burials rich in gold

2.1 The language groups and their distribution 51

KOGUI

IKA

YUKPA

BARÍ

Maracaibo

VENEZUELA

YARU RO

CUIBA

SÁLIBA

HITNÜ

TUNEBO

PIAROA

YAVITERO(†)

PUINAVE

BANIVA DEL

GUAINÍA

CURRIPACO

ACHAGUA

CUBEO

NUKAK

YURUTÍ

KAKUA

GUANANO

TARIANA

Bogotá

TINIGUA

PIJAO(†)

CARIJONA

PISAMIRA

CARAPANA

TATUYO

DESANO

BARÁ

CABIYARÍ

BARASANA

MACUNA

TANIMUCA

PIRATAPUYO

TUCANO

TUYUCA

HUPDÁ

CARIJONA

YURÍ

MIRAÑA

TICUNA

YAG UA

COCAMA

RESÍGARO

OCAINA

BORA

NONUYA

ANDOQUE

OREJÓN

ANGUTERO

SECOYA

TETETÉ (†)

MAKAGUAJE

SIONA

KOREGUAJE-

TAMA

TOTORÓ

Popayán

PÁEZ

Cali

EMBERÁ

Quito

TSAFIKI

AWA

PIT

KAMSÁ

Medellín

OPÓN-

CARARE(†)

EMBERÁ

CHIMILA

Cartagena

CUNA

WAUNANA

COLOMBIA

PERU

ECUADOR

PANAMA

B

R

A

Z

I

L

C

au

c

a

R

.

M

a

g

d

a

l

e

n

a

R

.

S

a

n

J

u

a

n

R

.

A

t

r

a

t

o

R

.

E

M

B

E

R

Á

E

M

B

E

R

Á

T

I

M

O

T

E

(

†

)

P

A

R

A

U

J

A

N

O

G

U

A

J

I

R

O

D

A

M

A

N

A

K

A

N

K

U

Í

(

†

)

P

I

A

P

O

C

O

G

U

A

Y

A

B

E

R

O

G

u

a

v

i

a

r

e

R

.

S

I

K

U

A

N

I

M

e

t

a

R

.

G

U

A

M

B

I

A

N

O

CHA’PALAACHI

I

N

G

A

N

O

C

O

F

Á

N

P

u

t

u

m

a

y

o

R

.

C

a

q

u

e

t

á

R

.

H

U

I

T

O

T

O

M

U

I

N

A

N

E

Y

U

C

U

N

A

S

I

R

I

A

N

O

J

A

P

R

E

R

I

A

GUAJIRO

recent expansion

Map 2 The Chibcha Sphere: approximate distribution of indigenous languages (mid twentieth

century). The shaded area surrounding Lake Maracaibo indicates a recent expansion of the

Guajiro language.

52 2 The Chibcha Sphere

(Chaves et al. 1995). The surviving descendants of the Sin´u, who live at San Andr´es de

Sotavento (C´ordoba), not far from the town of Sincelejo, have no record of their origi-

nal languages. The language of the lower Magdalena river (between Tamalameque and

Trinidad) was known as Malib´u.Itand the extinct languages of neighbouring peoples,

such as the Mocana and the Pacabueyes,have been grouped with the (Chibchan) lan-

guage of the Chimila by Loukotka (1968: 244) without any factual basis (cf. Constenla

Uma˜na 1991). The Chimila language is still spoken today. The language of the Tairona,

whowere destroyed in 1600 after almost a century of warfare with the colonists of Santa

Marta, may have been related to (or even identical with) one of its Chibchan neighbours

further east in the Sierra Nevada.

2

The Andes northeast of the Chibcha heartland were inhabited by several agricultural

highland peoples who shared some of its cultural characteristics. They include the Lache,

wholived near the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy (northeastern Boyac´a), the Guane in the

southern part of Santander department (south of Bucaramanga) and the Chitarero of

the Pamplona area (department of Norte de Santander). The Agatano occupied the

mountains west of V´elez (Santander). Most of these peoples have been classified as

Chibchan, although there are hardly any linguistic data to support such a supposition.

Since the territory of the Lache bordered on that of the modern (Chibchan) Tunebo or

Uwa of the eastern Andean slopes and lowlands in Casanare, it is tempting to speculate

that they represented the same linguistic grouping. Here again, however, the necessary

data on Lache are lacking. The Venezuelan Andes form a geographical continuation of

the area just referred to. The high Andes of the states of M´erida and Trujillo comprise

a substantial indigenous (now Spanish-speaking) population, representing the (extinct)

Timote–Cuica family, not related to Chibchan. In the pre-Andean hills of the states of

Lara and Falc´on, the Jirajaran family (also extinct) constituted another linguistic isolate.

Cariban-speaking peoples survive in the Colombian–Venezuelan border area west of

Lake Maracaibo (Yukpa and Japreria). Elsewhere in the northern Andean region the

identification of Cariban languages has been problematic as a result of their poor docu-

mentation and early extinction. In addition, Spanish chroniclers did not employ the term

‘Carib’ (caribe) primarily as a linguistic concept, but rather as a cover term for Indians

who remained intractable in their contacts with the colonial authorities, and, especially,

for those who used arrow-poison and practised cannibalism. Such tribes inhabited the

2

The linguistic connection between the area of Santa Marta and the Muisca highlands of Bogot´a

is illustrated by Piedrahita’s account of the conquest of 1537. In 1676 he wrote: Quienes m´as

percibieron el idioma fueron Peric´on, y las Indias, que se llevaron de la costa de Santa Marta, y

R´ıo Grande, que con facilidad lo pronunciaban, y se comunicaban en ´el con los Bogot´aes (‘Those

who best understood the language [of the Muisca] were Peric´on [the expedition’s guide] and the

Indian women, who hailed from the coast of Santa Marta, and the R´ıo Grande [Magdalena], who

with ease pronounced it, and communicated in it with the Bogot´aes’; Ostler 2000, following Uhle

1890).

2.1 The language groups and their distribution 53

Magdalena valley, where at least one group, Op´on–Carare, has been identified as Cariban

on linguistic grounds (Durbin and Seijas 1973a, b). In the case of other Magdalenan

peoples, such as the Panche and the Pijao,aCariban affiliation remains hypotheti-

cal, although the poor lexical data of the Pijao language that are left exhibit traces of

Cariban influence in its basic vocabulary (cf. Constenla Uma˜na 1991: 62). Cariban influ-

ence in the Magdalena valley is also suggested by its unique Carib-sounding toponymy

(Coyaima, Natagaima, Tocaima), which is found in both the ancient Panche and Pijao

areas. In other areas, however, where a Carib presence has been suspected mainly on

cultural grounds, e.g. in the Cauca valley, there is no linguistic evidence to support it.

In addition to Cariban and Chibchan, two more families which have their origin out-

side the northern Andes are found in the area under discussion. The Arawakan family

of probable Amazonian origin is represented near the Caribbean coast (Guajiro and

Paraujano). The Quechuan group (cf. chapter 3) is represented by the Inga or Ingano

language in the southern Colombian departments of Nari˜no and Caquet´a. The influence

of Quechua is particularly noticeable in the southern Andes of Colombia, notwith-

standing the fact that local languages, such as Pasto, Quillacinga and Sindagua contin-

ued to remain in use for a long time. It is not unlikely that Quillacinga and Sindagua

survive in present-day Kams´a or Sibundoy and in (Barbacoan) Cuaiquer or Awa Pit,

respectively (Groot and Hooykaas 1991). The department of Nari˜no, bordering on

Ecuador, has a substantial indigenous population, even though the use of Spanish is now

predominant.

The extent of Quechua influence in southern Colombia, as well as the moment of its

introduction, is a matter of debate. It may already have been present before the arrival of

the Spaniards, or it may have been introduced by the yanacona (serfs) from Quito, who

accompanied Belalc´azar and other conquistadores on their expeditions. The Quechua-

speaking yanacona played an important part in the conquest of New Granada. They were

eventually allowed to settle down at several locations north of Popay´an, in the Bogot´a

area and in Huila (Triana y Antorveza 1987: 118–20). As early as 1540, Andagoya (1986:

133) observed a sort of mixed use of Quechua and Spanish among the Jitirijiti tribe, who

lived in the neighbourhood of the present-day town of Cali. He quotes the words of a

recently christianised Indian woman turning down an improper proposal made to her by

a Spaniard: mana se˜nor que soy casada y tern´a Santa Mar´ıa ternan hancha pi˜na, ‘no,

sir, I am married, and the Holy Mary will be very angry’; cf. Quechua mana ‘no’, anˇca

pin

y

a ‘very angry’ (tern´a and ternan may represent the Spanish verb tendr´a ‘he/she will

have’). In 1758 the Franciscan friar Juan de Santa Gertrudis visited the archaeological

remains at San Agust´ın, leaving a detailed account of his findings (Reichel-Dolmatoff

1972). He reported that Quechua, la lengua linga (an adulteration of la lengua del Inga

‘the language of the Inca’), was used in the Upper Magdalena region, an area which had

been highly multilingual in the sixteenth century (Triana y Antorveza 1987: 169).