Zdunkowski W., Trautmann T., Bott A. Radiation in the atmosphere: A course in Theoretical Meteorology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6.9 Radiative equilibrium 195

time very tedious to use. Bruinenberg (1946), also using M¨ollers absorption data,

devised a numerical integration method for the calculation of radiative temperature

changes. His method revealed some details of the radiative temperature change

profiles that could not be obtained with the more crude graphical integration proce-

dures. Brooks (1950) simplified this numerical method. Hales (1951) was the first

to develop a graphical method to calculate radiative temperature changes. A similar

procedure was given later by Yamamoto and Onishi (1953).

Nowadays practically all calculations are carried out with high-speed computers

making it possible to attack many problems that were impossible to handle earlier.

Nevertheless, the earlier important research was carried far enough to analyze

and comprehend many of the interesting problems associated with radiative

transfer.

6.9 Radiative equilibrium

In the final section of this chapter we wish to explore in some depth the concept

of radiative equilibrium. Consider a horizontally homogeneous atmosphere where

radiative cooling and heating is the only process to form the vertical temperature

profile, that is other types of heat transfer such as heat conduction, convection and

latent heat release are ignored. If this atmosphere approaches thermal equilibrium,

i.e. ∂ T (z)/∂t = 0 at all levels z, the atmosphere has reached radiative equilibrium.

Since we assume the existence of a horizontally homogeneous atmosphere, the

condition describing radiative equilibrium implies a vanishing vertical divergence

of the radiative net flux density.

With the exception of spatially very limited regions around kinks in the vertical

temperature profile, long-wave radiation causes atmospheric cooling in the free

atmosphere which is stronger practically everywhere than direct solar heating.

Some numerical results of radiative temperature changes are given, for example,

by Liou (2002). The resulting cooling by radiative transfer must be compensated in

some manner since the atmospheric temperature does not decrease permanently. In

the real atmosphere, such compensating heating effects are turbulent heat transport

and the liberation of latent heat due to water vapor condensation. Apparently no

tropospheric layer is in radiative equilibrium.

It appears that Emden (1913) was the first to investigate the atmospheric tem-

perature profile resulting from the condition of radiative equilibrium. He found a

strong superadiabatic temperature gradient in the lower troposphere and a uniform

temperature of −60

◦

C in higher atmospheric layers. However, the height of the

computed tropopause somewhere between 6 and 8 km was too low. Certainly, the

superadiabatic lapse rate resulted from the disregard of all processes other than

radiative heating. Since the calculated stratospheric temperature at the tropopause

196 Two-stream methods for the solution of the RTE

agreed remarkably well with observations it was erroneously concluded that the

stratospheric temperature can be satisfactorily explained by the radiative equilib-

rium of water vapor alone.

The agreement between Emden’s calculation and observations of the strato-

spheric temperature was due to a lucky choice of the magnitude of the gray

absorption coefficient of water vapor, which was assumed to be the only atmo-

spheric absorber. By subdividing the water vapor spectrum into two parts and

approximating each region by a different gray absorption coefficient, still a very

poor approximation, M¨oller (1941) showed that even in higher layers the temper-

ature continues to decrease to values as low as −100

◦

C. The absorption of solar

radiation influences this result to a very small extent only. This should refute the

idea that the stratospheric temperature can be explained by the radiative equilibrium

of water vapor alone.

While it is still worthwhile to discuss Emden’s model, it is more instructive

for us to follow Goody’s (1964a) more modern treatment, which is based on the

solution of the radiative transfer equation in the form discussed earlier. We start

out by repeating the monochromatic RTE for a nonscattering medium in local

thermodynamic equilibrium

µ

d

dτ

I

ν

(τ,µ) = I

ν

(τ,µ) − B

ν

(τ ) (6.141)

Integration of this equation over the unit sphere yields

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ ) = 2π [I

+,ν

(τ ) + I

−,ν

(τ )] − 4π B

ν

(τ ) (6.142)

Here, we have introduced mean values of the upward and downward directed

radiances as defined by

I

+,ν

(τ ) =

1

0

I

+,ν

(τ,µ)dµ, I

−,ν

(τ ) =

1

0

I

−,ν

(τ,µ)dµ

(6.143)

which is equivalent to the assumption of isotropic radiation in the upward and down-

ward direction. E

net,ν

(τ )isthemonochromatic net radiative flux density. According

to (1.37c) this quantity may be expressed as

E

net,ν

(τ ) = 2π

1

0

I

+,ν

(τ,µ)µdµ − 2π

1

0

I

−,ν

(τ,µ)µdµ = π[I

+,ν

(τ ) − I

−,ν

(τ )]

(6.144)

whereby in the integrals the radiances have been approximated by their isotropic

values.

6.9 Radiative equilibrium 197

Differentiation of (6.142) with respect to τ results in

d

2

dτ

2

E

net,ν

(τ ) = 2π

d

dτ

I

+,ν

(τ ) +

d

dτ

I

−,ν

(τ )

− 4π

d

dτ

B

ν

(τ ) (6.145)

Multiplying (6.141) by µ and integrating the result over the unit sphere gives

2π

d

dτ

1

0

µ

2

I

+,ν

(τ,µ)dµ +

1

0

µ

2

I

−,ν

(τ,µ)dµ

= E

net,ν

(τ ) (6.146)

In this equation we again replace the radiances I

±,ν

(τ,µ) in the integrals by I

±,ν

(τ )

and obtain

2π

d

dτ

I

+,ν

(τ ) + 2π

d

dτ

I

−,ν

(τ ) = 3E

net,ν

(τ ) (6.147)

Substituting this equation into (6.145) finally results in a second-order ordinary

differential equation for the net flux density

d

2

dτ

2

E

net,ν

(τ ) − 3E

net,ν

(τ ) =−4π

d

dτ

B

ν

(τ )

(6.148)

For the solution of (6.148) we need to formulate two boundary conditions.

Combination of (6.142) and (6.144) gives

I

−,ν

(τ ) =

1

4π

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ ) −

1

2π

E

net,ν

(τ ) + B

ν

(τ )

I

+,ν

(τ ) =

1

4π

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ ) +

1

2π

E

net,ν

(τ ) + B

ν

(τ )

(6.149)

Evaluating these equations at the upper (τ = 0) and lower (τ = τ

g

) boundary of

the atmosphere yields

I

−,ν

(0) =

1

4π

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ )

τ =0

−

1

2π

E

net,ν

(0) + B

ν

(0)

I

+,ν

(τ

g

) =

1

4π

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ )

τ =τ

g

+

1

2π

E

net,ν

(τ

g

) + B

ν

(τ

g

)

(6.150)

In the case of monochromatic radiative equilibrium the divergence of the net

radiative flux density vanishes, E

net,ν

(τ ) must be constant throughout the entire

atmosphere, that is

d

dτ

E

net,ν

(τ ) = 0 =⇒ E

net,ν

(τ ) = E

net,ν

= const (6.151)

In this case the boundary conditions (6.150) reduce to

198 Two-stream methods for the solution of the RTE

B

ν

(0) B

ν

()

B

ν

()

B

g,

ν

=0

=

B

ν

(0)

Top of the atmosphere

τ

ττ

g

τ

τ

g

Fig. 6.7 Vertical distribution of B

ν

(τ ) for monochromatic radiative equilibrium.

At the top of the atmosphere the temperature adjusts itself to the net flux density.

(a) E

net,ν

= 2π B

ν

(0)

(b) I

+,ν

(τ

g

) = B

g,ν

= B

ν

(τ

g

) +

1

2π

E

net,ν

= B

ν

(τ

g

) + B

ν

(0)

(6.152)

Equation (6.152a) implies the assumption that no radiation is incident at the top of

the atmosphere, i.e. I

−,ν

(0) = 0.

Application of the equilibrium condition (6.151) to (6.148) results in

d

dτ

B

ν

(τ ) =

3

4π

E

net,ν

(6.153)

This differential equation may be easily integated yielding B

ν

(τ ) as a linear function

of τ

B

ν

(τ ) =

1 +

3τ

2

E

net,ν

2π

=

1 +

3τ

2

B

ν

(0)

B

g,ν

= B

ν

(τ

g

) + B

ν

(0) =

2 +

3τ

g

2

B

ν

(0)

(6.154)

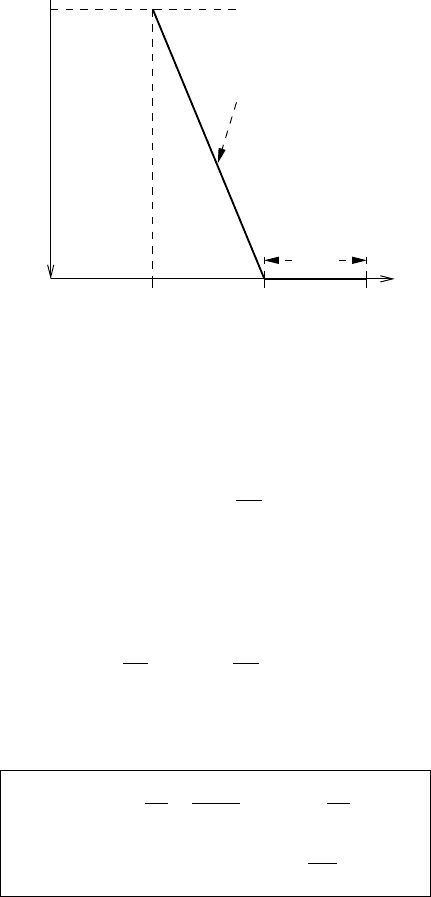

where use was made of the boundary conditions (6.152). Figure 6.7 depicts the

vertical profile of B

ν

(τ ) for monochromatic radiative equilibrium together with the

corresponding values at the boundaries of the atmosphere. At the Earth’s surface we

observe a discontinuity of the curve expressing a temperature jump T

g

between

the surface temperature T

g

and the lowest atmospheric layer T (τ

g

), i.e.

T

g

= T

g

− T (τ

g

) > 0 (6.155)

6.9 Radiative equilibrium 199

Emden’s investigation pertains to gray absorption since he approximated the

strongly varying water vapor spectrum by a single absorption coefficient. In order

to formally pass from the monochromatic to the gray absorption, we have to omit

the subscript ν in the previous equations. In this case the vertical temperature profile

of the atmosphere in radiative equilibrium as well as the temperature of the ground

are obtained from

T (τ ) =

π

σ

B(τ )

1/4

, T

g

=

'

π

σ

[B(τ

g

) + B(w = 0)]

(

1/4

with B(τ ) =

∞

0

B

ν

(τ )dν

(6.156)

For the temperature of the Earth’s surface we may also write

T

g

=

T

4

(τ

g

) + T

4

(0)

1/4

(6.157)

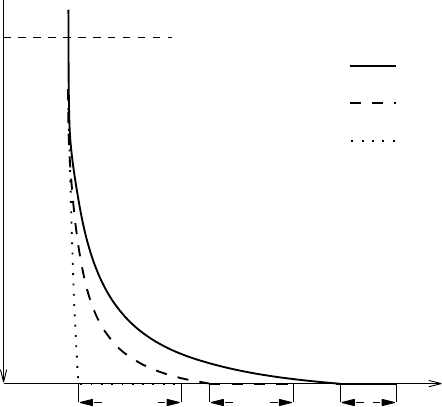

Figure 6.8 depicts qualitatively different vertical temperature profiles resulting

from different choices of the total optical thickness τ

g

. By considering only gray

absorption of water vapor in the troposphere, the height of the tropopause is given

by the optical top of the atmosphere, i.e. at τ = 0. Furthermore, in the stratosphere

the temperature distribution remains constant with height. The dotted curve shows

the situation with very weak absorption in the troposphere, that is τ

g,1

→0. In

this case B(τ ) and, thus, the tropospheric temperature remain nearly constant with

height. At the same time the temperature jump T

g,1

is largest. Evaluating for this

particular situation (6.157) yields a temperature jump of more than 47 K and 37 K

for T (τ

g,1

)=T (0) =250 K and 200 K, respectively. This means that T

g

decreases

with decreasing temperature at the tropopause.

From (6.154) we see that for a given B

ν

(0) with increasing total optical thick-

ness τ

g

the quantity B

g,ν

and, therefore, also T (τ

g

) are increasing. According to

(6.157) the values of T

g

are also affected thereof. To give a numerical example, for

T (0) = 200 K and T (τ

g

) = 250 K we obtain T

g

= 272.4 K, that is T

g

= 22.4K.

Choosing T (0) = 200 K and T (τ

g

) = 270 K yields T

g

= 288.4KorT

g

= 18.4K.

Hence, with increasing total optical thickness of the atmosphere the temperature is

increasing in the lower atmospheric layers while at the same time the temperature

jump is decreasing. In the limit of a very opaque atmosphere with an unrealistically

low temperature T (0) = 150 K and T (τ

g

) = 300 K, T

g

would be less than 5 K.

Goody (1964b) applied the radiative equilibrium model of the gray absorber by

assuming that the gray absorption coefficient and the absorber mass follow the same

height distribution. He also used a realistic temperature at the tropopause which he

estimated from a simple heat balance consideration assuming a mean global albedo

200 Two-stream methods for the solution of the RTE

∆T

g,1

∆T

g,2

∆T

g,3

=0

=

Tropopause

T

τ

ττ

g

τ

g,3

τ

g,2

τ

g,1

Fig. 6.8 Schematic vertical temperature distributions in case of a gray absorbing

troposphere for different values of the total absorber mass with τ

g,1

τ

g,2

<τ

g,3

and T

g,1

>T

g,2

>T

g,3

.

of 0.4. For τ

g

=1 he found T (τ

g

)= 259.7K,T

g

=22.8 K, while τ

g

=4 resulted in

T (τ

g

)=335.9 K and T

g

=11.3 K. At the same time the temperature gradients at

the ground were −∂T /∂z =19.5 and 36.0Kkm

−1

, respectively.

From the above findings we may conclude that the radiative equilibrium

model with gray absorption in the troposphere yields satisfactory vertical tem-

perature distributions in terms of lapse rates which are decreasing with height.

Moreover, by a fortuitous choice of all model parameters it is possible to obtain

relatively good values of the stratospheric temperature and the tropopause height.

However, the model also shows many deficiencies. The most important are listed

here.

(1) The temperature jump occurring at the Earth’s surface is unrealistically large.

(2) The lapse rates in the lowest atmospheric layers are distinctly too high in comparison

to the observed value of about 6.5Kkm

−1

.

(3) The temperature increase observed in the real stratosphere cannot be simulated with

the model.

(4) The stratospheric temperature T (0) is positively correlated with T

g

, see (6.157).

Certainly, there are many reasons why Emden’s model fails to produce better results.

Here, we mention the following shortcomings.

6.10 Problems 201

(1) The assumption of a gray absorbing atmosphere.

(2) The missing absorption of ozone in the stratosphere.

(3) The disregard of dynamic and thermodynamic processes in the lower troposphere.

Paltridge and Platt (1976) used simple arguments to show that even the

subdivision of the infrared spectral region into two subintervals, i.e. the almost

transparent atmospheric window and the remaining gray absorbing region, is suffi-

cient to achieve a decoupling of the stratospheric temperature from the temperature

of the Earth’s surface. Hence, with this simple treatment it is possible to obtain

warm temperatures at the ground, but at the same time cold stratospheric temper-

atures and vice versa. This is in accordance with observations in the tropics and

higher geographic latitudes.

M¨oller and Manabe (1961) successfully used the emissivity method to han-

dle the transfer problem. In addition to the water vapor absorption they included

the absorption effects of CO

2

and O

3

yielding more realistic temperature profiles

with temperatures increasing with height in the stratosphere. Manabe and M¨oller

(1961) carried out detailed calculations with a more refined model. They used a

time-marching procedure as the solution method starting out with an isothermal

atmosphere with the observed temperature at the Earth’s surface. However, this

method is very time consuming. Manabe and Strickler (1964) pointed out that it is

necessary to include various aspects of large-scale dynamics to obtain better results.

Apart from the inclusion of carbon dioxide and ozone they used a simple convective

adjustment scheme to account for the convective mixing and the latent heat release

in the lower troposphere. The resulting radiative–convective equilibrium showed

much more realistic temperature profiles than those produced by a pure radiative

equilibrium model.

6.10 Problems

6.1: Verify equation (6.8).

6.2: Verify equation (6.26).

6.3: In detail follow the steps from (6.92) to (6.95).

6.4: Consider the approximate treatment of scattering (Section 6.5) in the

infrared spectral region. For the conservative case ω

0

= 1 find the solutions

E

+

(τ ) and E

−

(τ ) for a cloud layer of optical thickness τ

c

. The boundary

conditions are given by E

−

(τ =0) =E

−

(0) and E

+

(τ =τ

c

)=E

+

(τ

c

).

6.5:

(a) Find the integration constants C

1

and C

2

in (6.95) by assuming the bound-

ary conditions E

−

(τ = 0) = E

−

(0) and E

+

(τ = τ

c

) = E

+

(τ

c

), where τ

c

is the

cloud layer optical thickness.

(b) Find the divergence of the net flux density, i.e. d(E

+

− E

−

)/dτ .

202 Two-stream methods for the solution of the RTE

6.6: Again we consider the approximative scattering in the infrared spectrum

as discussed in Section 6.5. For a cloud model consisting of three layers,

find expressions for the upward and downward directed flux density. Each

layer of optical thickness T

i

, i = 1, 2, 3 is homogeneous but of different

optical properties. Set up the required linear system which permits you to

determine the six integration constants C

1,i

, C

2,i

, i = 1, 2, 3. The required

boundary conditions and the continuity statements at the layer boundaries

are

E

−

(τ

1

E

−

(τ

2

E

−

(τ

1

=0)=E

−

(0)

= T

1

)=E

−

−

(=0)

E

+

(τ

1

= T

1

)=E

+

(

τ

2

τ

3

τ

3

τ

2

=0)

= T

2

)=E (=0)

E

+

(

τ

2

= T

2

)=E

+

(=0)

E

+

(τ

3

= T

3

)=E

+

(T

1

+ T

2

+ T

3

)

=0

= T

1

=0

= T

3

=0

= T

2

τ

1

τ

1

τ

1

τ

2

τ

2

τ

2

τ

3

τ

3

τ

3

6.7: In case of an isothermal and nonscattering atmosphere equation (6.95)

reduces to the so-called Schwarzschild equation. Carry out the reduction

assuming the boundary conditions E

−

(τ = 0) = E

−

(0) and E

+

(τ = τ

c

) =

E

+

(τ

c

).

Hint: Use Robert’s approximation, that is exp(−τ/¯µ) ≈ 2E

3

(τ ), see

(2.142), where ¯µ is an average value.

6.8: Carry out the required integration to show that (6.125) follows from (6.124).

6.9: The Sun may be treated as a black body emitting the largest amount of

energy at the wavelength of 0.5

µm. The Earth may also behave as a black

body in the spectral region of infrared emission. Which temperature will

the Earth assume if the incoming solar radiation and the outgoing infrared

radiation are balanced? Compare your result with the measured mean tem-

perature of 14

◦

C at the Earth’s surface (average value over all latitudes and

seasons) and explain the difference.

Required information: Sun’s radius, 695 300 km; distance Sun–Earth,

149 600 000 km; Earth’s radius, 6371 km; mean albedo of the Earth, 30%.

6.10: Set up the radiation budget at the top of the atmosphere and at the Earth’s

surface. The following quantities are given:

¯

A, mean absorption of solar

radiation by the atmosphere; A

tot

, global albedo (albedo of the entire sys-

tem); T

s

, radiation temperature of the black body surface of the Earth; T

a

,

radiation temperature of the atmosphere assumed to be gray; ε, thermal

emissivity of the gray atmosphere; and S

0

; solar constant.

6.10 Problems 203

(a) Find T

4

s

and T

4

a

from the budget equations.

(b) Assume

¯

A=0.26, A

tot

=0.31 and ε =0.8 to find numerical values of T

s

and

T

a

.

(c) Now suppose that the atmosphere is completely transparent to solar radiation

but completely opaque (ε =1) to thermal radiation. Find the new values of T

s

and T

a

.

(d) Suppose that T

s

is fixed at 283 K. For a given

¯

A=0.2 and A

tot

=0.30 find the

thermal emissivity and T

a

.

7

Transmission in individual spectral lines

and in bands of lines

High resolution spectroscopy reveals that the absorption and emission of radiation

by atmospheric gases is not continuously distributed over the entire spectral range.

In fact, the absorption and emission spectra are composed of numerous spectral

lines of different strength. Molecules have three different forms of internal energy

E

int

: rotational, vibrational and electronic. These energy forms are quantized and

are expressed by one or more quantum numbers. If a molecule absorbs or emits

radiation, a transition from one energy level to another takes place. During an

absorption process the molecule captures a photon thus reaching a higher level

of internal energy. Hence the molecule is said to be in an excited state. Emission

of radiation occurs if the molecule releases a photon resulting in a transition to a

lower energy level, that is, the molecule leaves the excited state. Both processes

yield spectral absorption and emission lines which are characteristic for a partic-

ular molecule. According to (1.15) the change of internal energy E

int

(ν)ofa

molecule resulting from the uptake or release of a photon is given by Planck’s

relation

E

int

(ν) =±hν (7.1)

where h is Planck’s constant and ν is the frequency of the absorbed or emitted

energy.

From these considerations one expects that each individual line has an infinitely

small width expressing the monochromatic absorption and emission of radia-

tion with frequency ν. In nature, however, it is observed that individual lines

do not have a zero line width, but they are broadened over a narrow fre-

quency range. This line broadening is caused by external influences affecting

the molecule during the absorption and emission process. There are mainly three

effects which are responsible for the broadening of spectral lines. These are listed

below.

204